Abstract

Background and Objectives

As more treatment options become available and supportive care improves, a larger number of people will survive after treatment for breast cancer. In the present study, we explored the experiences and concerns of female South Asian (sa) breast cancer survivors (bcss) from various age groups after treatment to determine their understanding of follow-up care and to better understand their preferences for a survivorship care plan (scp).

Methods

Patients were identified by name recognition from BC Cancer Agency records for sa patients who were 3–60 months post treatment, had no evidence of recurrence, and had been discharged from the cancer centre to follow-up. Three focus groups and eleven face-to-face semistructured interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, cross-checked for accuracy, and analyzed using thematic and content analysis. Participants were asked about their survivorship experiences and their preferences for the content and format of a scp.

Results

Fatigue, cognitive changes, fear of recurrence, and depression were the most universal effects after treatment. “Quiet acceptance” was the major theme unique to sa women, with a unique cross-influence between faith and acceptance. Emphasis on a generalized scp with individualized content echoed the wide variation in breast cancer impacts for sa women. Younger women preferred information on depression and peer support.

Conclusions

For sa bcss, many of the psychological and physical impacts of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment may be experienced in common with bcss of other ethnic backgrounds, but the present study also suggests the presence of unique cultural nuances such as spiritual and language-specific support resource needs. The results provide direction for designing key content and format of scps, and information about elements of care that can be customized to individual patient needs.

Keywords: South Asian women, breast cancer survivors, survivorship care, social and cultural aspects of cancer, psychosocial and physical functioning, life stage

1. INTRODUCTION

As more treatment options become available and supportive care improves, a larger number of people will survive after diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Currently, approximately 825,000 cancer survivors live in Canada (2.5% of the population)1, and more than 2.5 million breast cancer survivors (bcss), in the United States2. Because of the growing recognition of cancer survivorship as a distinct phase in the cancer trajectory, development of efficient and effective strategies or care plans for the organized transitioning of patients from active treatment at a specialized cancer centre to post-treatment care in the community is now being seen as critical to the overall health and well-being of patients3–8.

The U.S. Institute of Medicine recommends that cancer patients be provided with a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan that is clearly explained and reviewed with them upon discharge3. The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer has formed a National Survivorship Working Group whose current focus is the implementation of care maps and models of care to guide survivors and their caregivers4. However, the survivorship phase has its own unique issues for the cancer patient. In 2001, the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation identified the survivorship phase as the “continuing care” phase in its gap analysis report. It noted gaps of recovery and rehabilitation awareness, community supportive care, and consumer empowerment for cancer survivors1.

Studies show that bcss may feel isolated and uninformed after completion of treatment, when they have less interaction with oncology health professionals7,8. Survivors must also deal with the psychosocial effects of their breast cancer as they try to regain control over their lives and return to normalcy7. Results show that bcss may have persistent difficulties with fatigue, pain, sleep, psychological distress, fear of recurrence, family distress, concerns with employment and finances, information needs with respect to follow-up, and uncertainty about the future6–11. Those findings indicate a universality of physical, psychosocial, and practical experiences that echo most bcs needs; however, some variations between age groups have been reported, especially for groups at life stages correlating with human developmental changes6,11.

To help survivors deal with the impending potential side effects of cancer treatments, emphasis should be placed on the importance of continuity of care and of consistent communication between health care providers at the time of transition from completion of treatment to surveillance6. Continuity and communication help to reduce feelings of anxiety and abandonment at the point of discharge. Being attentive to the varying age-related needs of bcss is also important. Younger survivor age has been reported to be associated with greater care needs after treatment12,13. Evidence indicates that these younger survivors report high levels of concern for spouse and children, and feel overwhelmed by everyday life demands, especially when their children are relatively younger10–13.

Current research indicates that cancer is a complex disease for most women, not only in its physical manifestations, but also in its onset, diagnosis, treatment, uncertainty, and follow-up care10–14. Emerging research shows that survivorship issues may differ for various ethnic minorities in light of differing cultural beliefs that may be situated in religion, socioeconomic status, or politics14–21. Often, the notion of culture is suggested as possessing simplistic attributes of “common lifestyles, languages, behaviour patterns, traditions and beliefs”22. This naïve understanding of culture is limited and can inadvertently perpetuate stereotypes of a particular ethno-cultural group because of their differences from “mainstream society”21,22.

Evidence shows that ethnic minorities can face added challenges because of language barriers and cultural factors related to constructions by patients of health and illness, gender roles, and family obligations (for example, self-sacrifice)14–16. For African American, Latina, Asian, and Turkish women, family support and spiritual beliefs and practices are central to their coping15,16,23. With respect to quality of life for bcss, certain ethnic groups—particularly less acculturated Latina women—tend to do less well17,19. Evidence indicates that, for South Asian (sa) women, survivorship issues may differ from those of the general bcs population because of different understandings of the disease, language barriers, societal stigmas, and cultural and religious beliefs and values14,20,24–26.

Although there is movement toward providing customized care plans for bcss, little information is available to guide health care providers on how to manage this task for heterogeneous populations5,27. Challenges with respect to the making of recommendations for survivorship care planning, limited health care resources, and a large bcs population necessitate an efficient means of assessing individual needs and preferences for different ages and different groups of survivors6,16.

In the present research, women of sa heritage were chosen because people of sa descent represent the third-largest population group in British Columbia, many of whom reside in the various cities of the Lower Mainland28. South Asian women are identified as those of Indian ethnicity. In confronting the various challenges of cancer and its manifestations, female sa bcss may have experiences that are different from those of other female Canadian bcss14,20,24–26. Challenges may potentially arise because of concerns with migration and settlement issues, language barriers, and the learning of novel ways to establish a fresh life in the new country. Previous negative health care experiences, a preference of sa women for speaking with female health professionals, and feelings of social isolation and stigma in the community because of cancer may render this population more vulnerable, leading to unique impacts, concerns, and special needs after cancer treatment14,15,20,24,26,29. Gurm et al. also reported that some sa bcss appear distressed, with signs of depression, despite having undergone curative treatment, making it necessary to provide language-specific resources to sa bcss26.

Given the pre-existing challenges of developing and delivering survivorship care plans (scps) targeted to the general population, combined with challenges inherent to the heterogeneity and diversity among female sa bcss, it was deemed important to pursue the present qualitative study. We aimed to explore the experiences and concerns of female sa bcss after treatment to determine their understanding of followup care and to better understand their preferences for the content of a scp. We also examined how age and social and cultural influences may affect the experiences of sa bcss after treatment, especially as they transition from oncology to community care.

2. METHODS

At the BC Cancer Agency (bcca), where this study was conducted, the 5 regional cancer centres have a single electronic and paper charting system and a centralized transcription and letter dissemination process. Breast cancer patients who are finished active treatment are usually discharged to the care of their primary care physician within a year. The discharge letter contains guidance on appropriate surveillance tests and, where applicable, the recommended type and duration of adjuvant hormone therapy. No comprehensive individualized survivorship plan is generated for the discharged patient. The present study was conducted at 2 bcca centres located where a large proportion of the sa population in the province resides.

2.1. Patient Informants

A manual survey of the bcca’s Cancer Agency Information System identified sa breast cancer patients who had been seen by oncologists at the bcca Fraser Valley and Abbotsford centres from 2004 to 2007. During the survey, one researcher used name recognition to extract the records of patients with Indian surnames, forenames, or middle names from the database; the list was then checked for validity by another team researcher (both researchers are themselves of sa ethnicity). This process identified an initial 127 potential participants.

All potential participants were purposively checked against the study inclusion criteria, with close attention being paid to age, time since discharge from the bcca, and Indian subgroups recognizable by name. Inclusion criteria included initial referral to either of the 2 study centres; age between 18 and 85 years, with a diagnosis of nonmetastatic breast cancer; being 3–60 months post-treatment (could be on hormonal therapy); and no longer being followed by the bcca. The 60 eligible participants from among the initial 127 were then sent a letter of introduction and an invitation to participate in the study. Interested respondents contacted the researcher by mail or telephone. The researcher then contacted them by telephone to answer any questions. Only after a participant gave verbal consent were they advised of the focus group interview times. To improve response rates, a second mailing to nonresponders was initiated 2–3 weeks later. A total of 24 women agreed to participate.

2.2. Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board, with approval for the introduction and reminder letters and consent forms in English and in translated Punjabi versions (the largest sa subgroup residing in the surrounding geographic area spoke Punjabi). A descriptive qualitative approach fit this study, given that the purpose was to explore the subjective experiences of sa bcss in light of cultural, religious, social, and individual practices and beliefs that might reveal or explain the understanding of sa bcss about the period after breast cancer treatment in the context of their personal meanings for health and illness30. This inquiry choice lent itself to the collection of rich, detailed data that provided insight by describing how the experiences of sa bcss might differ from those of the majority of bcss after treatment31.

Semistructured interviews and field notes consistent with a qualitative methodology were used to conduct 3 focus group interviews with 13 participants and 11 one-to-one interviews. To ensure consistency, all interviews were conducted by the same sa researcher and facilitator (SSC)30. All participants were invited to the focus group interviews, which were conducted in a private bcca conference room in a social setting with refreshments. However, because of unavailability of transportation at the time of interviews, or because they did not want to be within a group setting or to come to the centre regardless of age or distance, 11 participants chose to attend one-to-one interviews at a place convenient for them. Both methods of interviewing and data collection were conducted in the same style; however, focus group participants were informed of the rules of conducting the focus group style of interview. Focus group interviews lasted 2–3 hours, and individual interviews lasted 25–40 minutes each. The use of thoughtfully prepared semistructured questions and of attentive and intuitive listening to participant responses, together with careful critiquing of each incoming interview ensured quality data that were rich and detailed30,31. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Initially, participants received a verbal explanation in one or a combination of English, Punjabi, Urdu, and Hindi from the researcher or facilitator before signing an ethics-approved Punjabi or English written informed consent. Interviews began only after participants fully understood the procedure and signed the informed consent. Women were encouraged to speak in their language of preference for ease in describing their personal experiences. Most chose to speak in Punjabi, some in Hindi or Urdu, and others in English. Some began in English and then chose to express themselves in their native tongue, because English terms did not exist for particular experiences.

Semistructured questions were used as a guide to ensure that all informants were asked the same questions in more or less the same order30,31. Guiding questions posed to participants were these:

Could you share with me the impact of breast cancer treatment on you as a woman and as a sa woman?

After completion of your cancer treatment, if a care plan was given to you upon discharge to help you take care of yourself, what information should be included in it?

These initial questions were followed by direct questions posed to help elaborate on the women’s experiences so as to determine whether those experiences differed from the experiences of other mainstream bcss. This approach helped to provide a deeper understanding of how acculturation, age, and cultural and social factors may or may not influence the needs and concerns of female sa bcss post treatment. The number of participants was deemed appropriate when similar themes began emerging from the data, and similar stories were being heard. Toward the end of data collection and analysis, a decision was made to conduct a second interview with a participant in the 45–54 age group to validate data. This strategy of confirming and validating interview data proved to be effective because it allowed the participant to elaborate on her experiences; however, no new data were added.

2.3. Data Analysis

Analysis of the data took two forms: thematic and content analysis. Thematic analysis was used to identify common threads and patterns in the sa women’s experiences of breast cancer after treatment30. Audio-recorded interviews and field notes were checked line-by-line for accuracy before analysis began. The NVivo 8 software (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia), a computer-assisted qualitative data management program, was used to code, store, and organize data. Research team members and coauthors met to read the two initial interviews, to discuss emerging categories, and to formulate a coding framework. Analysis was performed simultaneously with data collection by coding for similar categories and by constantly comparing data to identify recurring categories, emerging themes, and patterns30,31. This focused coding process helped to integrate the data and to describe larger segments of rich data that reflected emerging themes.

Demographics were used to group the women into various Indian subgroups with the aim only of showing variation in Indian subgroups, and not of performing a subgroup analysis. Participants were stratified into age groups after the interviews were complete. Initially, researchers were blinded to the various age groups, but once recurring patterns were revealed, data were extracted according to life stage, resulting in these age groups: <44, 45–54, 55–64, and >65 years.

At this point, a tabulated matrix of major themes was identified, allowing for constant comparative analysis across the age groups to identify and confirm themes and patterns that were prevalent in each area explored30. This constant comparison of categories and emerging themes allowed the research team to critically examine their own biases and to be reflective when identifying themes30,31. The research team met regularly to discuss the final coding scheme, because the initial coding moved from categories to a more abstract, higher order of themes and patterns that described the experiences of the sa bcss in light of age and social and cultural aspects.

Content analysis was used to systematically identify the preferences of sa bcss for scp content by explicitly coding the data into categories after an initial line-by-line reading32. The codes were important to identify content and to provide descriptive names—that is, categorizing labels of the experiences of the participants of the impact of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment30. This strategy helped to classify broad categories and to characterize the perceptions of sa bcss of their individual needs and experiences after treatment. Thematic and content analysis were both needed to fully describe the subjective experiences of sa bcss after treatment and their preferences for scp content. Research members were satisfied that the data analysis had reached saturation when no more themes or patterns emerged.

For 2 interviews in which women spoke English, Punjabi, and Hindi simultaneously, two sa team members checked and compared for accuracy and reliability the English translation and the interpretation of the Punjabi and Hindi audio-recorded interviews. Strategies including the use of various data collection tools, concurrent data collection, and analysis of incoming data with modification of interview questions to elicit more in-depth data helped to confirm conceptual development of the findings30,31. Detailed record-keeping of interviews, field notes and observations, and any changes to the guiding questions ensured auditability30,31. The process of establishing a connection and rapport with the bcss and closely listening to their narratives during interviews helped us as researchers to stay close to the experiences of the informants30. In addition, researcher triangulation, redundancy of themes, and the processes of critical writing and reflection about assumptions and stereotypes helped team members to avoid imposing their own ideas and interpretations throughout data collection and analysis, thereby fostering objectivity30.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

Table i shows the characteristics of the study population. The 24 participants ranged in age from 28 to 75 years (mean: 55.5 years; median: 54.0 years). The groups interviewed using the two qualitative data collection methods (focus groups and one-to-one semistructured interviews) did show any intergroup differences. Stratification at participant recruitment achieved an even distribution of 6 participants for each age group. It was important to achieve an even distribution of age groups so as to note any variation because of age in this ethnic group. Age stratification also provided a meaningful stratification of life stage, because it corresponded to the perimenopausal and postmenopausal times of life; to periods of child-bearing or child-rearing (<44 years); to employment (45–54 years); and to the approach of retirement (55–64 years) or retirement itself (>65 years). In the study cohort, 6 women were retired, 2 were on disability leave, 8 had never worked or did not work, and 8 were currently employed.

TABLE I.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Value (n) |

|---|---|

| Participants | 24 |

| Age group | |

| <44 Years | 6 |

| 45–54 Years | 6 |

| 55–64 Years | 6 |

| >65 Years | 6 |

| Language preference | |

| Punjabi | 8 |

| Hindi/English | 5 |

| Urdu | 1 |

| Punjabi/English | 10 |

| Country of origin | |

| India | 17 |

| Fiji | 6 |

| Pakistan | 1 |

| Religion (self-reported) | |

| Sikh | 17 |

| Hindu | 5 |

| Christian | 1 |

| Muslim | 1 |

| Education | |

| No school | 3 |

| Elementary | 2 |

| High school | 12 |

| College | 5 |

| University | 2 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 7 |

| Unemployed | 8 |

| Disability | 2 |

| Retired | 6 |

| No response | 1 |

| Treatment received | |

| Surgery | 5 |

| Surgery and chemotherapy | 9 |

| Surgery and radiation | 3 |

| Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation | 4 |

| Hormonal therapy | 7 |

| No response | 3 |

| Post-treatment duration | |

| 4–12 Months | 1 |

| 13–23 Months | 3 |

| 24–35 Months | 13 |

| 36–47 Months | 4 |

| No response | 3 |

With respect to language, 8 women spoke mainly Punjabi; 10, Punjabi and English; 5, Hindi and English; and 1, Urdu. Although demographic data pertaining to religion and migration status were not collected, all women self-identified their religious affiliation, and some identified their number of years as residents in Canada. During the thematic analysis, we found that, by itself, religion did not influence the interpretation by these women of the meaning of the illness or their post-treatment experiences, but that religious, cultural, and social influences were used as a filter or medium through which the women’s stories were culturally described. Delineating religious, cultural, and social influences was complex, because those factors were all integrated and intertwined—not static, but constantly shifting22. Number of years of residency in Canada and immigration status were not sought because no examination of those factors was intended; the aim was to explore the experiences of Indian women regardless of birthplace. Of the study participants, 50% had a high-school education, with a third had attended college or university. The rest had either elementary or no formal education. Most of the women were 2–3 years post-treatment. Most rated their overall health as excellent, good, or fair. All had regular male or female family physicians. The family physicians were a mix of Indian ethnicity and other, mainly English-speaking, ethnicities.

3.2. Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to describe the experiences of our study cohort with the impact of breast cancer after treatment and their understanding of follow-up treatment. Themes in this study are reported as either “universal” or “unique” to the sa women interviewed in light of their cultural identity influenced by social and cultural nuances.

In this study, “universal” themes are those that emerge from post-treatment experiences and that are similar to the themes of bcss of other ethnic origins and geographic settings. It was clear that these universal late effects were experienced by sa bcss in ways that are unique to the complex nature of their social and cultural influences, thereby highlighting diversity among bcss. Poignant experiences of sa bcss highlighted how their experiences of post-treatment impacts matched with or varied from those of women in other cultural groups as they accessed health care in Canada.

For the purposes of the present study, “unique” themes are those that emerged from health care experiences situated in the context of the sa women’s meaning and understanding of disease and illness, possible migration, and acculturation experiences in light of social context and cultural expectations20,24–26,33–38.

Results are presented as “universal” themes, with the uniqueness of the experiences of sa women highlighted, and themes “unique” to sa women. The major overarching theme unique to sa bcss was identified as “quiet acceptance.” Table ii sets out the major themes.

TABLE II.

Themes representing the experiences of participants

| Themes | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Universal | Unique to South Asian women |

| Physical impact | Quiet acceptance |

| Fatigue (loss of energy or physical strength) | Acceptance (faith and inner strength) |

| Cognitive changes | Acceptance (karma and fate) |

| Loss of libido; menopause or sexuality issues | Quiet (social network context) |

| Nerve damage and pain | Family and community |

| Reproductive or pregnancy issues (unique concerns of South Asian woman) | Hounsla (hope and courage) |

| Psychosocial impact | Peer support |

| Body image, sexuality | |

| Depression (stress in my mind and heart) | |

| Fear of recurrence and uncertainty | |

| Intimacy and relationships | |

3.3. Universal Themes of the Impact of Breast Cancer After Treatment

Table iii presents selected quotes from the interviews relating to universal themes.

TABLE III.

Verbatim quotes relating to universal themes

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Physical impact | |

| Fatigue (loss of energy or physical strength) | I was feeling very fatigued, weak after the chemo and radiation. I didn’t have that much energy, but as time goes by, I am getting the strength back. (Age 41) I had no idea how tired I was going to be. I still feel fatigued ... as if there is no strength in my body. (Age 66) My lymph node was taken out, that is why I have still a problem with my arm. I don’t lift heavy things. I have lost strength and cannot hold with this hand. I still have some problem. My muscle is still is weak. (Age 54) |

| Cognitive changes | I can’t remember things as well as I used to. (Age 47). It takes a while to remember things; it’s hard to go back to work. (Age 52). |

| Loss of libido; menopause and sexuality issues | Like sexual relation ... I don’t have any interest in it at all. (Age 39) I don’t know.... I just lost interest after the chemo and stuff. (Age 48) You feel unattractive, and you feel the guilt because you do not have any interest in having sex. I was scared ‘coz, and I was [emphasis] scared that he is going to go away, right? (Age 50) |

| Nerve damage and pain | After 4 years, I still have some numbness. I feel itchy, and I scratch. And I don’t have any feeling here anymore. This was after radiation. (Age 28) In my fingertips, my palms, my feet. When you wake up in the morning, it’s like you are walking on broken glass. (Age 50) I try sweeping, and this joint here hurts. The doctor said my nerves have been removed from here. (Age 75) |

| Reproductive or pregnancy issues (unique concerns of South Asian woman) | You know in our culture after the wedding we do need a child soon. (Age 28). So when you see other people got married after your marriage ... and they have two kids ... three kids, then you feel really bad [sniff]. (Age 28) I have my whole family here, but they don’t talk to me because of my love marriage. It’s been almost 5–6 years now but we don’t have a child yet because of my treatment. But my husband is really supportive, but I sometimes I feel bad, and I cry when I am sitting alone, because I didn’t get a baby yet, right? (Age 28) |

| Psychosocial impact | |

| Body image, sexuality or reconstruction | I wear East Indian suits. You want to look nice, but in my mind I know there isn’t a breast here. Other people can’t see that. I want to be normal, like a lady. (Age 50) I am coping with it, but I don’t even feel like dating, because I feel like I am missing a part of my body. I am kind of conscious about my body. (Age 50) It’s my body image. You know, sometimes when I am dressing, I don’t even look at that part. I avoid looking at it in the mirror. (Age 50) |

| Depression (stress in my mind and heart) | Depression, I used to get it a lot in my mind, in my heart. I used to feel like crying. My mind used to get upset. I am getting better now, but it still bothers me. (Age 43). Sometimes now I can’t breathe very good when my mind gets depressed. (Age 57) You know, I feel crying every day. I am so stressed out I don’t feel like talking to anyone. Nobody’s home.... I just stay inside the house I am so depressed. (Age 47) |

| Fear of recurrence and uncertainty | I always worry about mets going to other parts of the body. I do worry, especially when I hear people dying from breast cancer. That hits me; I get really sad. (Age 41) |

| Intimacy and relationships | It was really tough in the beginning. My husband was really good ... very supportive. He wasn’t, you know, pushy or any of that stuff; he was very patient with me when it came to, you know, intimacy. (Age 28) It’s hard to talk to my husband because we don’t talk about these things. (Age 54) |

3.3.1. Physical Impacts

The theme of physical impact was described as making the most impression because of the debilitating nature of the side effects of cancer treatments, coupled with reproductive, hormonal, and aging processes, and loss of the ability to continue employment for most sa women less than 64 years of age. This theme highlighted how bcss tried generally to learn and to adapt to the practical tasks of activities of daily living, and changed their original ways of doing things as they dealt with physical deficits associated with the cancer diagnosis and its treatment.

3.3.2. Fatigue: Loss of Energy and Physical Strength

Fatigue was identified as the main physical impact by women of all age groups; however, women more than 65 years of age resigned themselves to the fact that their fatigue might might be attributable to their age or the hormonal therapy they continued to take. Women in all groups spoke of “having lower energy than I should have.” Others identified fatigue as a loss of physical strength that drained the body of the physical capacity they had before cancer treatment.

Although this theme was universal, some uniqueness was expressed in the 45–54 and 55–64 age groups. Some women experienced fatigue together with a loss of energy and of the ability to mobilize themselves as easily as they could before, especially when their employment entailed heavy lifting or using their arms on a continuous basis in industry-related work such as sewing, operating machinery, or farming. These sa women were concerned that the physical impacts of cancer treatments would limit the type of work they would be able to return to or do in the future. It is understood, however, that this concern is not unique to sa bcss, but applies to the migrant population who may be reduced to working under strenuous conditions when their family income depends on both spouses being gainfully employed. Two-spouse incomes are more central in an immigrant population in which vocational options may sometimes tend to be more physical in nature, with longer hours of employment. Women said that being counselled about the long-term side effects of surgery and cancer treatments should be explained in terms of the practical implications for function and quality of life.

3.3.3. Cognitive Changes

Cognitive changes such as decreased memory, decreased ability to concentrate, impaired word retrieval, and difficulty organizing thoughts were identified. These changes were noticed more by participants who were less than 44 years of age; however, there wasn’t as much emphasis placed by participants generally.

3.3.4. Loss of Libido and Menstruation and Sexuality Concerns

Loss and irregularity of menses, together with hot flushes, were experienced mostly by women in the younger age groups (<44 and 45–54), especially those on hormonal therapy. Loss of libido concerned women who felt that they should have some desire to have sex with their spouses, but this loss of interest “after the chemo and stuff” led them to feel guilty as wives within their relationships. However, most felt relieved when spouses were supportive.

3.3.5. Nerve Damage and Pain

Participants from all four age groups complained of nerve damage and pain to various degrees, which got in the way of daily tasks and day-to-day living. Women were concerned by the effects on simple household tasks such as sweeping the floor or lifting heavy dishes. The older women also recognized that some of the pain might be related to the aging process, but younger women (<44 and 45–54) were concerned about the duration of these problems in light of their continued employment. The women said that information about these possible toxicities should be explained or described in the context of the resulting constraints and potential chronicity, especially in light of productivity at work and daily living.

3.3.6. Reproductive and Pregnancy Issues: Unique Concerns of SA Women

Although reproductive and pregnancy issues are universally experienced by women, some of the related cultural and social contexts are unique to the experiences of sa women. For example, 2 of the women less than 30 years of age felt cheated when they were diagnosed and treated for cancer at an early age. They were concerned about the impact that their situation would have on their marriage. Participants from all groups spoke about how childbearing and the addition of children to the family is a highly valued and emphasized role of women in sa culture and society compared with Western society—creating added pressures that make it harder to bearing the cancer diagnosis and treatment.

A 28-year-old participant, separated from her family because she had chosen to marry someone her family did not approve of, was distraught because she knew that she could not conceive children while on hormonal therapy, causing her grief as she struggled with adherence or nonadherence to hormonal therapy. This woman felt that her story might have more of a positive feel, because she at least had a good relationship with her husband and her mother-in-law, who were supportive; however, she felt that, for most younger sa women, a diagnosis of breast cancer was a much bigger burden because it was coupled with cultural and societal expectations of women bearing children within the first years of marriage. For those reasons, participants felt that health care providers should inform their patients about the side effects of cancer treatments—especially the long-term effects on hormones and reproduction—so that women could make informed decisions.

3.4. Psychosocial Impacts

For most sa women, the psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer and completing treatment had a profound impact “mentally and emotionally, because you are just not the same person afterwards” (participant age 50). These sa women reported psychosocial impacts of cancer treatment experiences that had some resonance with the universal effects voiced by other ethnic groups; however, they also reported struggles with language barriers and a limited ability to navigate the health care system because of recent migration to Canada—situations that are not unique to sa bcss, but that are common for most migrant populations. Most participants self-reported either migrating to Canada between 3 and 40 years earlier or being born in Canada. The women’s experiences were also influenced by prior health care experiences in their own country, meaning that the emotional and psychosocial impacts labeled as “universal” are coloured by the uniqueness of being a sa woman with personal contextual factors of social and cultural values and beliefs.

3.4.1. Body Image, Sexuality, and Reconstruction

The universal themes of body image, sexuality, and reconstruction affected not only how sa women felt about themselves, but also how they orchestrated themselves in the community after being diagnosed and treated for cancer. Younger women (<44 years of age) did not seem to voice concerns about body image or sexuality as much as did women in the older age groups (45–54 and 55–64). That difference may be a result of priorities being placed on concerns about reproduction and pregnancy. Women felt that their body image, their sexuality, and their reasons for breast reconstruction were all tied into the identity of a woman who has to make decisions for breast reconstruction after reconsidering her personal need for feeling whole.

3.4.2. Depression: “Mental Stress in My Mind and Heart”

Although stories of depression told by the women had universal resonance, their experiences are again understood in the context of cultural and social nuances. These sa bcss shared stories of sadness and generally not wanting to be involved in family and community activities. Younger sa women (<44 years of age) experienced depression related to reproductive issues associated with the cancer diagnosis, because the diagnosis changed the normal cycle of life. Older women (>65 years of age) experienced only slight bouts of depression when they were originally diagnosed; they were more accepting of their situation. By contrast, women in the 45–54 and 55–64 age groups were very vocal about the depression they had experienced since diagnosis. They felt that they did not receive adequate patient support and counselling from the bcca or their family physician, especially in their own language, which prolonged the depression. Some women in these age groups felt that counselling about the impact of diagnosis and treatment should have been provided from the beginning so that they could prepare for the side effects of depression and distress. The reported experiences and recollections of these women indicate either that counselling information was not apparent to them or that they felt uncomfortable in asking for resources.

3.4.3. Uncertainty and Fear of Recurrence

Uncertainty and fear of recurrence was also a universal theme. Factors commonly leading to uncertainty for all age groups included lack of clarity about normal healing, lack of information about lifestyle choices, confusion about side effects, and ambiguity about follow-up care recommendations and resources. Although some sa bcss from all age groups shared their concerns about uncertainty and fear of recurrence, younger women (<44 years of age) were more emotional in their responses because of worry that the cancer might recur and because of the unknown future. Women in the middle age groups (45–54 and 55–64) were more concerned about what would happen to their children if the disease came back. The oldest participants (>65) were mostly not concerned about recurrence or uncertainty.

3.4.4. Intimacy and Relationships

In all age groups, most women realized that they had the support of their spouses while going through cancer diagnosis and treatment—especially when some participants did not feel like having sex, but wanted intimacy in other ways. However, several women had flirted with the idea of divorce because of the lack of support displayed by their husbands. One woman realized that negative conditions were already present in the relationship, but the significance of those conditions was heightened by the lack of support she felt after her cancer diagnosis and during treatment. At the time of the interview, she was considering a separation.

4. THEME UNIQUE TO THE RESPONSE OF SA WOMEN TO THE IMPACT OF BREAST CANCER AFTER TREATMENT: QUIET ACCEPTANCE

“Quiet acceptance” was the major theme that emerged from the experiences of sa women with the impact of a breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. This theme tries to capture a variety of factors such as age, religion, meanings of health and illness, and the complexity of social and cultural situations that contribute to the “uniqueness” of sa women, who may appear quiet—accepting and dealing with the cancer diagnosis, treatment, and discharge to the community. As a theme, “quiet acceptance” reflects the sa bcs’s sense of who “she” is because of her religious beliefs and cultural upbringing and how she uses those experiences, rather than the values central to being a sa woman, at the survivor stage of coping. The richness of these women’s experiential stories of breast cancer, captured in their own language—Punjabi, Hindi, and Urdu, with or without English—defines the “cultural identity” that affects a sa bcs’s grasp of the meaning of illness across varying age groups, migration statuses, acculturation, education, socioeconomic statuses, and other cultural factors15,37. Although participants touched on universal themes of uncertainty and fear of recurrence, depression, fatigue, and reproductive issues, they did not share experiences of “I am going to battle” or “I am going to overcome” cancer as did bcss in another study6. It is therefore important to understand that the sa bcs’s lens maybe coloured by an Eastern spiritual influence in which the “self’ may be different from the Western concept of “self.” This major theme of “quiet acceptance” encompassed subthemes of faith and inner strength; fate and karma; family and community; hounsla (hope and courage); and social or peer support.

Most women from the oldest age group (>65 years of age) accepted the cancer diagnosis and treatment in a very matter-of-fact manner, especially now that they had reached the end of active treatment. Those in the <44, 45–54, and 55–64 age groups felt more emotionally responsible for their children and families, who might suffer despite the woman’s acceptance of her own fate. However, most women realized that the cancer diagnosis—and their treatment and prognosis—was a part of their lives, and they acknowledged it as such. It was evident that “quiet acceptance” had complex meanings that did not totally depend on age or subgroup. Table iv provides verbatim quotes from women of all subgroups and religions relating to this unique theme.

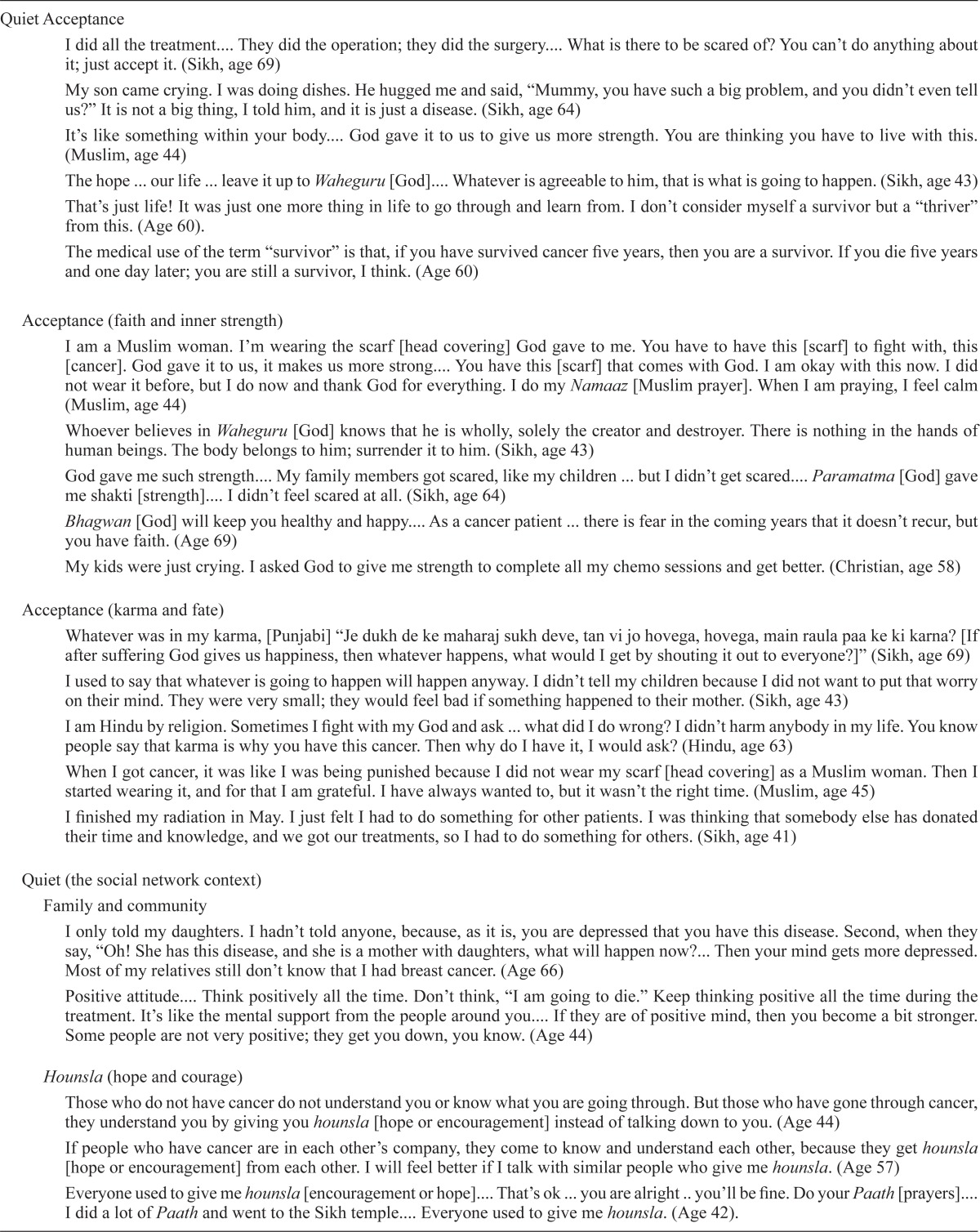

TABLE IV.

Verbatim quotes relating to the theme unique to South Asian women

| Quiet Acceptance | I did all the treatment.... They did the operation; they did the surgery.... What is there to be scared of? You can’t do anything about it; just accept it. (Sikh, age 69) |

| My son came crying. I was doing dishes. He hugged me and said, “Mummy, you have such a big problem, and you didn’t even tell us?” It is not a big thing, I told him, and it is just a disease. (Sikh, age 64) | |

| It’s like something within your body.... God gave it to us to give us more strength. You are thinking you have to live with this. (Muslim, age 44) | |

| The hope ... our life ... leave it up to Waheguru [God].... Whatever is agreeable to him, that is what is going to happen. (Sikh, age 43) | |

| That’s just life! It was just one more thing in life to go through and learn from. I don’t consider myself a survivor but a “thriver” from this. (Age 60). | |

| The medical use of the term “survivor” is that, if you have survived cancer five years, then you are a survivor. If you die five years and one day later; you are still a survivor, I think. (Age 60) | |

| Acceptance (faith and inner strength) | I am a Muslim woman. I’m wearing the scarf [head covering] God gave to me. You have to have this [scarf] to fight with, this [cancer]. God gave it to us, it makes us more strong.... You have this [scarf] that comes with God. I am okay with this now. I did not wear it before, but I do now and thank God for everything. I do my Namaaz [Muslim prayer]. When I am praying, I feel calm (Muslim, age 44) |

| Whoever believes in Waheguru [God] knows that he is wholly, solely the creator and destroyer. There is nothing in the hands of human beings. The body belongs to him; surrender it to him. (Sikh, age 43) | |

| God gave me such strength.... My family members got scared, like my children ... but I didn’t get scared.... Paramatma [God] gave me shakti [strength].... I didn’t feel scared at all. (Sikh, age 64) | |

| Bhagwan [God] will keep you healthy and happy.... As a cancer patient ... there is fear in the coming years that it doesn’t recur, but you have faith. (Age 69) | |

| My kids were just crying. I asked God to give me strength to complete all my chemo sessions and get better. (Christian, age 58) | |

| Acceptance (karma and fate) | Whatever was in my karma, [Punjabi] “Je dukh de ke maharaj sukh deve, tan vi jo hovega, hovega, main raula paa ke ki karna? [If after suffering God gives us happiness, then whatever happens, what would I get by shouting it out to everyone?]” (Sikh, age 69) |

| I used to say that whatever is going to happen will happen anyway. I didn’t tell my children because I did not want to put that worry on their mind. They were very small; they would feel bad if something happened to their mother. (Sikh, age 43) | |

| I am Hindu by religion. Sometimes I fight with my God and ask ... what did I do wrong? I didn’t harm anybody in my life. You know people say that karma is why you have this cancer. Then why do I have it, I would ask? (Hindu, age 63) | |

| When I got cancer, it was like I was being punished because I did not wear my scarf [head covering] as a Muslim woman. Then I started wearing it, and for that I am grateful. I have always wanted to, but it wasn’t the right time. (Muslim, age 45) | |

| I finished my radiation in May. I just felt I had to do something for other patients. I was thinking that somebody else has donated their time and knowledge, and we got our treatments, so I had to do something for others. (Sikh, age 41) | |

| Quiet (the social network context) | |

| Family and community | I only told my daughters. I hadn’t told anyone, because, as it is, you are depressed that you have this disease. Second, when they say, “Oh! She has this disease, and she is a mother with daughters, what will happen now?... Then your mind gets more depressed. Most of my relatives still don’t know that I had breast cancer. (Age 66) |

| Positive attitude.... Think positively all the time. Don’t think, “I am going to die.” Keep thinking positive all the time during the treatment. It’s like the mental support from the people around you.... If they are of positive mind, then you become a bit stronger. Some people are not very positive; they get you down, you know. (Age 44) | |

| Hounsla (hope and courage) | Those who do not have cancer do not understand you or know what you are going through. But those who have gone through cancer, they understand you by giving you hounsla [hope or encouragement] instead of talking down to you. (Age 44) |

| If people who have cancer are in each other’s company, they come to know and understand each other, because they get hounsla [hope or encouragement] from each other. I will feel better if I talk with similar people who give me hounsla. (Age 57) | |

| Everyone used to give me hounsla [encouragement or hope].... That’s ok ... you are alright .. you’ll be fine. Do your Paath [prayers].... I did a lot of Paath and went to the Sikh temple.... Everyone used to give me hounsla. (Age 42). | |

| Peer support | Because nobody knows the other person when they are telling their story, which is okay. Because some women who feel shy and may like this kind of group.... Because everybody is talking. They feel okay and will share.... You feel relaxed. (Age 44) |

| I think the only person I really listened to were people who had cancer ... and had gone through it already. (Age 62). | |

| You’re not always able to speak to family. No matter how close you are to the family, you’re not always able to speak to them.... The intimacy ... you know ... the very private parts such as those between you and your husband. (Age 50) | |

One of the interview questions aimed to explore the meaning of being a survivor. The focus was to attempt to understand how sa bcss perceive the concept of being a “breast cancer survivor.” Feelings about being called a survivor were mixed, especially in light of other tragedies that people usually survive, such as train or car crashes. Many women disliked being called a “survivor”; rather, they wanted to be called “thrivers.” Participants accepted the diagnosis and treatment and realized that this journey was a personal one, having nothing to do with surviving anything. For most women, the notion of “survivor” was a more Western concept connected with behaviours of “battling the cancer” or “overcoming the cancer.”

4.1. Acceptance: Faith and Inner Strength

Most women from all the various age groups and subgroups described how their faith gave them an inner strength that helped them to face the cancer diagnosis and related treatments and to continue after being discharged. Among these women, Waheguru (God), Sacheya Patshah (True King), Guru [God (Sikh)], Bhagwan (God), Maharaj (King), Paramatma [Supreme Soul (Hindu or Sikh)], Rabb [God (Muslim or Sikh)], and Shakti [strength (Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh)] were the words most commonly used to describe inner strength. These various words described a god who instilled faith into them and who gave them inner strength, thereby helping them through the suffering and struggles of living, of which the cancer diagnosis and its treatment were a part. Verbatim excerpts provided in Table iv illustrate the richness of each of the stories that was the foundation of the deep faith expressed.

4.2. Acceptance: Karma and Fate

Most of these sa women seemed to accept the cancer diagnosis as their fate (part of their karma and of being human), allowing them to accept treatments and to move into the post-treatment phase. However, acceptance did not mean that they moved into the next phase without apprehension and uncertainty about the future. Women in the younger-to-middle age groups still had concerns for their young children who needed them emotionally. Participants used “karma” in the context of the suffering that humans have to endure as part of “their past lives” and “punishment for their sins.”

Some women were vivid in their descriptions and acceptance of their destiny in this life; however, they also understood that they could change or “turn” their karma by good deeds that could lessen their current suffering and alter the outcome of the cancer diagnosis.

4.3. Quiet: The Social Network Context

Social support included family, extended family, the sa bcs community, hounsla, and social and peer support

4.3.1. Quiet: Family and Community

For most sa women, extended family and community were generally an important part of the social support system, especially when family or community members provided transportation for those who lacked the ability to drive to the agency for their numerous treatment-related appointments or acted as interpreters when participants were faced with language barriers. These sa women saw those actions as being very supportive, and yet there was a complexity concerning who in the family or community should be privy to the woman’s breast cancer diagnosis because of the stigma associated with the disease within the community. Participants felt that the community response was fear associated with cancer. They shared responses such as “She is going to die now,” “This is a horrible disease,” and “Everyone gets scared just by the name.”

Women in the middle and older aged groups had additional concerns related to marriage prospects for their unmarried daughters. Would their daughters be eligible for marriage to good suitors? Breast cancer in the mother might mean that a daughter could have breast cancer as well, making matrimony with the daughter a higher risk for the future husband’s family. Some women explained that the cancer diagnosis had to be kept secret from most of the family and community so as to keep the daughters from being marred as unmarriageable—a situation that became burdensome and non-supportive for these particular families as a whole. One participant, widowed for 19 years and living with her two daughters, described her struggles with family and community as being fraught with sadness.

4.3.2. Quiet: Wishing for Hounsla

The need for privacy and having to be secretive about the diagnosis and related treatments added a sense of isolation and burden for sa women as they went for months of chemotherapy or radiation, or both. Some women occasionally felt that support from family and community was negative, because people visited only to appear to be doing the right thing socially. These women were not happy with the negative response they received from the “well-wishing” visitors because “they did not give person hounsla,” “they just come and disturbed you,” and “the relatives say, ‘Ha! How did it happen?’ ”

Some women tried to stay positive and to have hounsla although they were stressed. Some women described that hounsla was hope to “maintain your strength to go through the cancer diagnosis and treatment.” Participants felt that social support provided by the immediate and extended family members and by the community in the form of hounsla is important because it reduces depression and enhances quality of life. Nevertheless, they sometimes still felt alone because they felt that family members could not share their suffering. These contextual social and cultural factors tended to leave most sa bcss in the 45–54 and 55–64 age groups feeling isolated and depressed—emotions that led to hopes of being able to share their suffering with members of the cancer community, preferably others from their own ethnic community.

4.3.3. Quiet: Wishing for Peer Support

Most women felt that sharing with others who had gone through similar experiences was more meaningful, thereby providing social support that would enhance quality of life for sa women who felt shy and who had language barriers. Some women also felt that having a support system within the sa group would be beneficial. Most women found that they could talk with family or community members who were already cancer survivors because they received hope from each other.

The concept of peer support or mentoring seems to be an integral part of the larger social support system, hounsla, and health and well-being for sa women. For most women, this meant that they could share their personal cancer experiences within their own cultural and social context, in their mother tongue, making the exchange more meaningful and supportive.

5. CONTENT OF THE SCP

The content analysis utilized in this study found that perceptions of the content of the scp by most sa bcss echoed the perceptions of white female bcss in another Canadian study, with emphasis placed on an individualized scp6. Participants from all age groups indicated a need for a record of the diagnosis, the types of treatment given, and the prognosis. This information was important because they felt that the scp should be portable to wherever they might relocate in future. Participants preferred a written, language-specific (especially for those who spoke only their own language) care plan in a booklet format. Most participants preferred that the nurse deliver the scp, although some preferred to receive it from the oncologist. This preference showed no variation with age group. Table v summarizes the desired content of the scp.

TABLE V.

Survivorship care plan (scp) content

| Essential Core Elements for All Life Stages | Preferred Format for All Age Groups |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

5.1. Information Needs and Resources

These sa bcss felt that, coupled with the treatment summary, not only should they receive a list of resources, including those for reconstruction, reproduction, sexuality, nutrition, exercise, and prevention, but that the resources should be explained at discharge. Most participants felt that the scp should be initiated at the start of treatment so as to provide a complete understanding of the possible side effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment (such as depression and physical and psychosocial effects).

Some participants felt that survivors would derive benefit from physical activities such as walking during and after treatments. They felt that this suggestion should be communicated early so that they could overcome fatigue, depression, and weight gain during active treatment and afterwards. Some women indicated that they “didn’t stop exercising, but went to the gym during chemo. After the chemo, I would eat my chapatti and go for a walk. This helped me from getting tired” (participant age 43). Others felt that being inactive was the worst thing, because it led to more feelings of depression. Being active helped to “motivate myself and go for it, because nobody else can help me in this case” (participant age 44).

The desire that the scp contents include a treatment summary and resources was universal, but most sa bcss also described a need for community peer-support resources. This need may be unique to sa women because of the stigma attached to a cancer diagnosis and the associated need for privacy. It was especially true for women who felt more burdened and depressed when the community stigmatized cancer as a “horrible disease that meant a death penalty.” Formal or informal peer support from people who speak the same language was especially valued, because participants could not always confide in or burden family members. Other participants felt that formal counselling in their own language would also be helpful because they could describe their feelings much better in their own language.

6. DISCUSSION

Cancer survivorship, most commonly defined as the period after primary adjuvant treatment has ended and before the onset of advanced disease, has become recognized as a distinct phase of the cancer trajectory with its own unique issues for the cancer survivor3–5,29. However, concern remains about what is done and said during treatment that might set the stage for survivorship.

The U.S. Institute of Medicine3 and the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer4 have b oth identified cancer survivorship as a top priority. Both agencies want to ensure that patients and their families receive enhanced care through a coordinated approach with a view to a healthier life after treatment. In light of the current recommendations and because there are, to date, no published studies concerning sa bcss and their perceptions of scp delivery, the present qualitative study explored the experiences and concerns of sa women, examining how acculturation experiences and social influences affect the experience of breast cancer after treatment is completed. At the same time, the preferred content and format of a scp for this population has been suggested, taking into consideration cultural and social differences. Related studies with sa or immigrant women from diverse countries of origin have shown that the cancer experience might be coloured by difficulties related to the immigration experience itself and to living in a new and different culture22–26,34. Those difficulties include a wide range of stressors, including financial burdens, uprooting and resettlement experiences, challenges in providing adequate health care for family members, and maintenance of the activities of daily living22,24–26,34–38.

Although the acculturation experiences of sa bcss will vary depending on the number of years of residency in Canada, it is important to remember that, much as has happened for other migrant populations, the highlighting of health care practices among immigrant women can lead to the essentializing and further stereotyping of cultural practices and beliefs that inform the particular group’s health care practices. Descriptive findings tend to serve as a distraction from the clinical setting residing within the larger social and institutional context21,22.

“Quiet acceptance” was the overarching theme uncovered by this study, with culture, social milieu, and religion being the foundational lens through which quiet acceptance, karma or fatalism, inner strength, and familial and community support were viewed for the women interviewed. The interplay of religion, culture, and quiet acceptance has been documented as a large part of how most people of sa ethnicity orchestrate their daily lives34–38. However, health professionals should be aware that culture is a complex and dynamic aspect of individuality, not something static that each member of a community possesses20–23. Consistent with those findings, other researchers working with similar population also reported that spirituality is the ultimate context within which sa women experience a cancer diagnosis and treatment14,24–26,37,38. Acceptance of the diagnosis and proceeding through treatment using prayer as a coping mechanism is recognized as strength. Furthermore, other studies have reported the use of religion as a coping strategy by sa cancer patients in India36–39 and by patients diagnosed with depression in England38. Women of other ethnicities have also reported that spirituality and prayer provided them with inner strength to live through the cancer journey6,11,23,39.

The notion of karma and rebirth (belief that what a person does in each life influences the circumstances and predispositions experienced in future life) is important for most sa patients and has ramifications for the ethical delivery of health care37. Unlike sa women, white bcss were seen, in a study by Smith et al. from Vancouver Island, to embrace the Western tendency to “battle” or “overcome” the cancer, leaving survivors constantly struggling for a cancer cure instead of journeying through a healing process6. Conversely, the appearance of passive and quiet acceptance by sa woman of the impact of a cancer diagnosis and treatment should not be underestimated. The experiences of universal themes by these women were intertwined with a cultural and social uniqueness beyond the mainstream bcs. Recognizing the behaviours that mimic quiet acceptance by most sa bcs is therefore crucial when providing cancer care. The danger of writing about the quiet acceptance perspective of sa bcss is that such exposition might unintentionally reproduce essentialized notions about how sa bcss want or need to be treated21–25.

In the literature, sa populations have generally been identified as having strong family and community support14,24–26,37. However, that finding might not hold true for all sa women. Some may lack supportive families and encounter unbending role expectations from family members, such as being expected to resume all household and childcare responsibilities after treatment26. Social and cultural differences, such as a belief in passive fatalism—that life is in God’s hands and that a cancer diagnosis is the result of karma—have been documented for women reflecting on their cancer diagnosis14,24,26. Nonetheless, such beliefs are not held by all sa women, especially given differences in Indian subgroups, in acculturation, and in age, socioeconomic status, and education. It is thus important that health care providers avoid stereotyping, but try to assess for diversity of language and country of origin and to take into account each patient’s uniqueness14,22,26,35.

The present study confirms findings from the earlier-mentioned study by Smith et al.6 and from other studies17–18,40–42 that there are universal physical and psychosocial effects of breast cancer treatment that persist among bcss of all ethnicities. Those effects include difficulties with fatigue, pain, psychological distress, fear of recurrence, family distress, concerns about employment and finances, and uncertainty over the future. Notably, although some of those impacts might seem universal, their meaning for sa patients is in fact quite different. Contextual factors such as migration and acculturation, socioeconomic status, and gender in the various ethnic populations residing in Western society today create a cultural lens that influences how, compared with a mainstream population, members of those ethnic populations journey through the cancer trajectory13,24–26.

It is imperative that all women, regardless of ethnicity, be given attentive cancer care. Respectful care—that is, listening for a woman’s individual and specific needs—moves beyond culturally specific care. This notion of respectful care is exemplified in a study in which female sa cancer survivors reported that acknowledging the individual as a woman first, and then as a cancer patient, helps to build the professional–client relationship, thereby developing trust13. The need for supportive care was noted by Howell et al. in their systemic review of reported organizational system components for survivorship, psychosocial, or supportive care. They recommended that patient access to survivorship care be a specific component of cancer care, with development of specific programs that take into consideration the diverse backgrounds and geographic location (especially remote and rural settings) of survivors42,43. South Asian bcss have also expressed a willingness to declare their diagnosis with peers, and many value the emotional and informational support that they receive from others with a similar diagnosis, clearly expressing the importance of social support within the cancer community26.

Longitudinal studies have confirmed fatigue as the most prevalent physical effect after breast cancer treatment40,44,45. However, these sa women reported that pain and nerve damage were also largely responsible for a decline in quality of life that limited their ability to function at their previous jobs46. Those reports represent another example of the need for possible toxicities to be explained or described in the context of constraints on living and potential chronicity, especially in light of expected productivity at work and in activities of daily living for sa bcss.

Besides uncertainty and fear of recurrence as psychosocial impacts, our sa women reported depression as a predominant factor hindering their ability to function socially. The stigma of cancer and depression affected their access to social support from family and community. Karakoyun–Celik et al. reported a correlation between the depression and anxiety levels of bcss, mostly heightened because of fear of recurrence and lack of social support23. The depression, pain, and high levels of nerve damage mentioned by sa bcss may be intertwined with social, religious, and cultural factors that are highly complex and difficult to pinpoint for the average health professional, especially when somatic pain symptoms are very real for the individual experiencing them. That difficulty was confirmed in a study by Raguram et al., who reported a positive relationship between severity of depressive symptoms and scores on the stigma scale in somatization of symptoms that affected the ability to work and function socially for women in South India46. Stigma from cancer has been seen to have a huge negative impact on how cancer patients cope with their diagnosis; the correlation of stigma and cancer can therefore lead to depression and then to somaticism24,47. Bailey et al.47 suggested that an assessment of depressive stage in these patients should include the culture and the perceptions of the patients concerning diagnosis and treatment of their cancer and the illness itself. Other studies have emphasized the need for accurate and complete assessment of depressive symptoms24,36–37. Studies suggest that overemphasis on pain could be an expression of depression for sa women in whom pain is somatized for depression38,46,48.

Although sa women in the present study alluded to depression in the presence of the cancer diagnosis alone, it is vitally important to assess for pre-existing conditions of isolation and depression that might be heightened because of the new illness. It is standard procedure at the bcca to provide information about available counselling services at the initial new patient appointment. In addition, the treating centres administer a P-Scan (screen for depression or distress) to every new patient. Automatic counselling referral could be generated for those deemed at high risk. However, most sa women in the current study did not “present” as having a risk for depression on the P-Scan, a generic screening tool that is available only in English. This generic Western approach may have missed the diagnosis of depression in sa breast cancer patients. However, sa bcss should not be stereotyped, and health professionals should be careful not to overgeneralize the idea that culture is something possessed by certain groups, because such an approach risks constructing a community as a “cultural minority” or “other,” even when many subgroups may constitute the larger community21.

In the present study, the sample size of 24 participants was ample for a qualitative inquiry, especially given the even distribution into age groups and subgroups among the sa bcss30. Despite efforts to recruit women from all the various groups, participants declined inclusion because of work, lack of transportation, or family commitments. Participants in one-to-one interviews chose the evening for the interview because of unavailability in the daytime. In the present work, differences between age groups were meaningful, highlighting the varying psychosocial, emotional, and practical needs of the women, especially those related to reproduction, hormonal therapy, employment, and retirement. However, obtaining a larger number of women for each group would have produced data highlighting variations within the stratified age groups6,12,41,42. Although our findings are not generalizable to sa women in other settings, some cultural similarities might cross boundaries. Our findings also indicate that women of all ethnicities may be more similar as bcss, especially in light of the universal impacts of treatment, and yet identifying individual cultural differences that are unique is important. Demographic data concerning age, language, education level, type of treatment, and time since discharge from the cancer centre were obtained, but number of years of residence in Canada would have provided more insights in the context of prior health care experiences and acculturation.

7. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CANCER CARE PROVIDERS

It is vitally important that providers of cancer care to women and families of all ethnic groups remember not to make the assumption that patients who do not ask questions do not want information or do not need help understanding cancer treatment. Related research with immigrant sa women has found that health care providers neglected the health care needs of those patients and brushed them off because they did not always ask questions20,24,35. Patients may not be presenting as emotionally or psychologically concerned because they are accepting of whatever treatments are being provided; an individual assessment of their understanding and needs therefore remains important before proceeding with treatments. Conducting a psychological assessment of prior and continuing depression and distress is important to make recommendations for counselling and to ensure the ability to adhere to adjuvant therapy after primary treatments. Providers should inquire about the patient’s existing social supports and their access to those supports so as to prevent isolation.

A second recommendation would be to inquire about the patient’s work and life situation. This knowledge is important because many patients will have to return to their original employment to support the family. Physical limitations might affect a patient’s ability to perform certain duties, making the return to work impossible. Discharging patients to the care of the family physician with clear instructions for the patient is important, especially instructions on how to interact with employers who require bcss to perform at an optimal level. Providing a detailed follow-up care plan that empowers the patient is essential, especially for the psychosocial status of the patient and family. Integrating a person-centred cancer care approach will ensure that the patient understands the importance of follow-up care and has the opportunity to express concerns. To that end, the expertise of trained personnel should be applied: an oncology nurse, for example, might act as a “transition coordinator” and implement the scp by reviewing the scp with the patient and the family during a formal discharge procedure. It has been reported that patients view the scp positively; however, some find the information too technical and lacking in adequate details about side effects and self-care strategies7. Patients have emphasized the importance of communication and a more realistic approach, with meaningful content in the scp so that it is used as a tool to enhance the patient’s quality of life in future.

Although the U.S. Institute of Medicine has recommended the development and implementation of scps, movement toward that end has been slow to take hold at most cancer centres3. Some of the barriers are insufficient consensus about the required content of the scp and insufficient staff time to prepare and deliver the scp43. Grunfeld et al.49 reported that scps are not seen as any better or different from the standard discharge or transfer to the community. However, that particular clinical trial was neither a longitudinal study nor an exploration of cultural or social factors that might be important to take into consideration, especially the ways in which people experience health and illness and their expectations for health care delivery.

The results of the present study highlight the importance of understanding how the needs of bcss from various ethnic groups—including the mainstream—differ when considering the preparation of follow-up care plans, especially in light of the social and cultural lens that will influence quality of life for those survivors after treatment. That understanding is important for empowering women in their self-care and ensuring that family physicians are adhering to the follow-up protocol recommended by the oncologist. It can help to prevent recurrence and psychological distress for the patient and family members. Our research team intends to conduct a pilot study to develop, implement, and evaluate scps that are individualized and targeted to the needs of female sa bcss. Research into, and evaluation of, scp implementation from the viewpoints both of health professionals and of patients will be relevant in standardizing the delivery of a scp upon discharge.

8. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Gurpreet Oshan, their sa research assistant, and the BC Cancer Foundation, which made the present work possible.

9. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no relationships with pharmaceutical companies and declare that no financial conflict of interest exists.

10. REFERENCES

- 1.Ward A. Cancer Survivorship: Creating Uniform and Comprehensive Supportive Care Programming in Canada. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society (acs) Learn About Cancer > Breast Cancer > Detailed Guide > What are the key statistics about breast cancer? [Web page] Atlanta, GA: ACS; 2010. [Available at: http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/BreastCancer/DetailedGuide/breast-cancer-key-statistics; cited December 20, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (cpac) Improving the Cancer Journey [Web page] Toronto, ON: CPAC; n.d. [Available at: http://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/priorities/cancer-journey/; cited February 9, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff AC. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S459–66. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SL, Singh–Carlson S, Downie L, Payeur N, Wai ES. Survivors of breast cancer: patient perspectives on survivorship care planning. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:337–44. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganz PA, Hahn EE. Implementing a survivorship care plan for patients with breast cancer. J. Clin Oncol. 2008;26:759–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller R. Implementing a survivorship care plan for patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:479–87. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.479-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, Davis WW, Brown ML. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322–30. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Short PF, Vargo MM. Responding to employment concerns of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5138–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyerowitz BE, Kurita K, D’Orazio LM. The psychological and emotional fallout of cancer and its treatment. Cancer J. 2008;14:410–13. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pauwels EE, Charlier C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lechner L, Van Hoof E. Care needs after primary breast cancer treatment. Survivors’ associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Psychooncology. 2013;22:125–32. doi: 10.1002/pon.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, Layne TM, Bach PB. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:101–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh–Carlson S, Neufeld A, Olson J. South Asian immigrant women’s experiences of being respected within cancer treatment settings. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2010;20:188–98. doi: 10.5737/1181912x204188192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]