Abstract

High Mobility Group A1 (HMGA1) encodes proteins that act as mediators in viral integration, modification of chromatin structure, neoplastic transformation, and metastatic progression. Because HMGA1 is overexpressed in most cancers and has transcriptional relationships with several Wnt-responsive genes, we explored the involvement of HMGA1 in Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling. In adenomatous polyposis coli (APCMin/+) mice, we observed significant upregulation of HMGA1 mRNA and protein in intestinal tumors when compared to normal intestinal mucosa. Conversely, restoration of Wnt signaling by zinc-induction of wt-APC resulted in HMGA1 downregulation in HT-29 cells. Because APC mutations are associated with mobilization of the β-catenin/TCF-4 transcriptional complex and subsequent activation of downstream oncogenic targets, we analyzed the 5′-flanking sequence of HMGA1 putative TCF-4 binding elements (TBEs). We identified two functional that specifically bind the β-catenin/TCF-4 complex in vitro and in vivo identifying HMGA1 as an immediate target of the β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling pathway in colon cancer. Collectively, these findings strongly implicate Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling in regulating HMGA1 to further expand the extensive regulatory network affected by Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling.

Keywords: Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 Pathway, High Mobility Group A1 (HMGA1), colon cancer, oncogene, TCF-4 target gene, transcriptional activation

INTRODUCTION

Cancer initiation and progression occurs through a multi-step mechanism resulting in the aberrant functions of tumor suppressors, oncoproteins, and proteins required for uncontrolled cellular proliferation, differentiation, and invasion.1–5 While a number of pathways have been implicated in cancer progression, dysregulation of Wnt signaling is most often associated with intestinal pathogenesis. Wnts are a family of secreted glycoproteins that transduce signals via adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC). In colon cancer, the inactivation of the tumor suppressor, APC, and/or deregulation of its associated transcription factors are the most common causes of disease.6–15 APC controls the cell’s shift into a hyperproliferative state and 80% of colorectal cancers result from its inactivation as a result of germ-line mutations.6 In its normal cellular context, APC complexes with Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 (GSK-3), casein kinase 1 (CK1), and Axin to promote proteosome-dependent degradation of β-catenin.16–19 Loss of APC function promotes the accumulation and subsequent nuclear translocation of β-catenin.14, 20 Once in the nucleus, β-catenin binds the T-cell factor-4 (TCF-4)/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF-1) forming a transcription factor complex involved in activating genes implicated in proliferation, transformation, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). 14, 20, 21 Although about 100 well-characterized down-stream targets of Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 like c-myc22,Cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2)23, Nr-CAM24, CD4425,26, Oct-427, Id328, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3)29 and c-jun/AP130 exist, the specific mechanisms of this pathway continue to emerge. The overall understanding of the APC/β-catenin/TCF-4 pathway inarguably suggests that abnormalities in this pathway confer malignant phenotypes.

The High Mobility Group A1 (HMGA1) gene encodes HMGA1a and HMGA1b, a class of nuclear phosphoproteins that modify chromatin structure to coordinate signaling events for embryogenesis, proliferation, transformation, invasion, and metastasis.31–37 Strong expression of HMGA1 occurs during embryonic development but there is typically no expression in adult normal tissues. Most human neoplasias have elevated levels of HMGA1 and ectopic expression of the HMGA1 gene promotes malignant phenotypes in vitro and in vivo.38–42 Consistent with its oncogenic potential, HMGA1 is required for proliferative phenotypes in various cancers including gastric, colon, prostate, and breast.43–53 Moreover, in many tumors, HMGA1 expression correlates with invasiveness and malignancy justifying its current exploration as a prognostic marker.54–56

Transcriptional upregulation of HMGA1 appears to be a universally important mechanism for its induction during cancer progression and metastasis. However, the specific details of its activation remain unclear. Several lines of evidence led us to postulate that Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 is involved in HMGA1 regulation. Global gene expression profiling from two independent studies identified HMGA1 as a distinguishing transcription factor enriched in colorectal cancer when compared to normal mucosa.44, 47 Mice bearing the HMGA1 transgene develop intestinal polyps and silencing HMGA1 expression in HCT116 and SW480 colon cancer cells inhibit tumor initiation and metastatic progression.57 Finally, HMGA1 shares transcriptional relationships with genes regulated by the Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 cascade. It is a c-myc target gene important in transformation of Burkitt’s lymphoma cells40 and also activated by c-Jun. 58, 59 Further, genes including STAT-3, Id3, and CD44 are activated by both Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling and HMGA121, 25, 28, 29, 60–63.

In the present study, two TCF-4 binding sites have been identified within the HMGA1 promoter that regulates its expression in colorectal cancer, implicating HMGA1 as a downstream mediator of aberrant Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

The human colon carcinoma cell line HT29 (wtAPC−/−) containing a zinc-inducible APC gene (HT29-APC) and a control cell line with an analogous inducible lacZ gene (HT29-β-gal) derivatives were provided by the laboratory of Drs. Ken Kinzler and Bert Vogelstein (The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Johns Hopkins University Medical Institutions, Baltimore) 22, 64 and maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin, 1% Amphotericin B, and 0.6 mg/mL Hygromycin B. To induce expression of full-length APC in HT29-APC cells, ZnCl2 (100μM) was added for the times indicated. The HCT116 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and were maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin. All cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% carbon dioxide.

RNA Extraction and Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR

Normal (C57BL/6; B6 mice) and APCMin/+ mice intestinal tumor samples were obtained from the University of South Carolina Animal laboratories (Columbia, SC). Because APC Min/+ tumors preferentially develop in the distal portion of the small intestine as well as the colon, 65 freshly dissected tumor and mucosa tissues were isolated from the small and large intestines of all mice and snap frozen. Total RNA from cells and from mouse tissues (typically 2 mg) were isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed on 1 mg of total RNA with Oligo(dT) primers and the Reverse Transcription System kit (Promega Corp, Madison, WI). 200ng of the cDNA template obtained from reverse transcription reactions were amplified with primers specific for HMGA1 (mmHMGI2F: 5′-GATGGGACTGAGAAGCGA-3′ and mm HMGI2R: 5′-CTTCTCCAGTTTCTTGGGTG-3′) and β-actin (mmβactinf: 5′-CTTCCTTCTTGGGTATGGAATCC-3′ and mm β actinr : 5′-GATCTTGATCTTCATGGTGCTAGG-3′). PCR consisted of 24 cycles to ensure that amplification was in the linear range and densitometry was performed on PCR products resolved on stained agarose gels in order to determine ratios of HMGA1/β-actin transcripts. Semi-quantitative densitometric analysis was conducted using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. Quantitative mRNA expression of HMGA1 in cell lines and mouse tumors and non-tumor intestinal mucosa specimens was determined using extracted RNA and predesigned primer and probe assays from Applied Biosystems and using the 7300 Fast real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Ct values were related to the endogenous control gene, β-actin (ΔCt) and the relative expression (2−ΔCt) was normalized to the average expression in untreated cells or non-malignant intestinal mucosa of APC Min/+ (2ΔΔCt).

Western blot analysis

Mouse tissues and cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (DOC), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 50 mM Tris HCl) with 1X HALT–EDTA protease inhibitor (Promega) and proteins extracted by homogenization. Protein extracts (20mg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked for one hour in 2% enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) western Plus blocking reagent (GE Biosciences) and incubated overnight with a polyclonal antibody against HMGA1 (1:500 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and β-actin (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The following day, membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T), incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies, and developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Biosciences). Due to the migration rate differences between the two proteins, probing for the internal control and the protein of interest were done simultaneously to confirm equal loading. Each band was quantified using QuantityOne software (version 4.6.1, BioRad) and normalized to β-actin.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assays

ChIP assays were carried out using a SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP kit with Agarose Beads following the manufacturer’s procedure (Cell Signaling). Briefly, 2.5 × 106 HCT 116 cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde (Pierce), lysed, and chromatin was sonicated to 0.2–1.0 kb. Sheared chromatin was incubated with either 3μg anti-TCF4 (Millipore), anti-β-catenin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling), or anti-Histone H3 (Cell Signaling) antibodies for five hours at 4°C and the DNA (2μl) extracted from each precipitated complex was used for amplification. PCR reactions were conducted using GoTaq Polymerase (Promega) and oligonucleotides (IDT) designed to amplify TCF4 binding elements 1 (TBE1; corresponding to −487 bp to −801 bp from TSS): 5′-GAAAGTTGGAAGCAGCAGAG-3′ and 5′-CACAGGATGTGTATGCTCAGC T-3′; TCF4 binding element 2 (TBE2; corresponding to −1247 bp to −1599 from TSS): 5′-CCCTTGGTCCAAGTTTCAAGAGTG-3′ and 5′-CCAAATAACTCTCTACTCACTGACCC-3′ within the HMGA1 promoter sequence taken from the NCBI Nucleotide database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, reference sequence AF286367.1). Oligonucleotides for the human RPL30 exon 3 (Cell Signaling) were included by the manufacturer and used as positive controls.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Analysis

Nuclear extracts from HCT116 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells were prepared using the nuclear protein extraction reagent (Pierce). Biotinylated oligonucleotides containing the TCF-4 consensus sequence (5′-(A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)GG-3′) found in the human HMGA1 promoter sequences 66 were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies) (Fig. 3a). For the DNA mobility shift assay, the binding reaction was performed for 30 min at room temperature in 20 μl of binding buffer containing 50 fmol of either wild-type or mutant biotin-labeled probe (Table 2), 1 μg of poly(dI·dC)·poly(dI·dC), and nuclear extract (3–5 μg). Double-stranded oligonucleotides without biotin (sense strand 5′-CTG GGT TGC CGG GCA ACT AAC-3′ and antisense strand 5′-GTT AGT TGC CCG GCA ACC CAG-3′) at a 200-fold molar excess were used as specific competitors while oligonucleotides corresponding to sequences within the coding region of HMGA1 were used as nonspecific competitors. For competition experiments, unlabeled oligonucleotides were incubated for 10 minutes prior to addition of the labeled probe. Separation of free biotinylated DNA from DNA-protein complexes was carried out on a pre-run 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5X Tris borate electrophoresis (TBE) buffer (45 mM Tris base, 45 mM boric acid, 25 mM EDTA) at 100 V. The gels were transferred to a PVDF membrane at 380 mA and cross-linked with UV light for 10 min. Membranes were then blocked, incubated with stabilized streptavidin, and developed with the ECL detection reagent using a light shift assay kit (Pierce). In the experiments where antibodies were used to characterize the protein-DNA complex, nuclear extracts were pre-incubated with the indicated amounts of each antibody for 20 min at room temperature followed by 20 min incubation with the biotinylated probe.

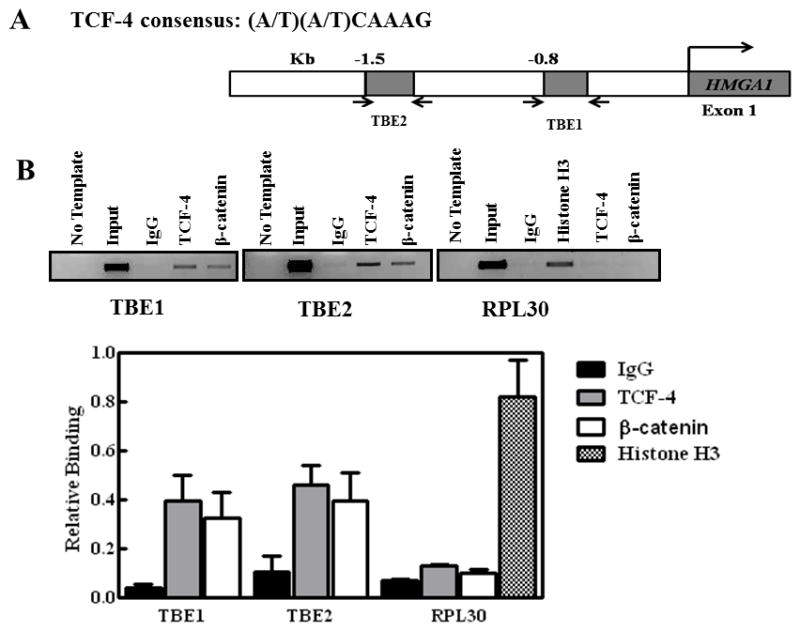

Figure 3. The β-catenin/TCF-4 complex binds directly to the HMGA1 promoter region containing the TCF-4 binding consensus in HCT116 cells.

(A) Identification of putative TCF-4 binding and response elements (TBEs) in the HMGA1 promoter. Sequence of the HMGA1 gene promoter is taken from the NCBI Nucleotide database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, reference sequence AF286367.1).

(B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments with sheared chromatin from HCT116 cells with endogenous overexpression of β-catenin and TCF-4 after cross-linking proteins bound to DNA with formaldehyde. The bar graph shows the percent of total input DNA immunoprecipitated with the following commercially available antibodies: rabbit Immunoglobulin G (IgG), TCF-4 (Cell Signaling), β-catenin (Santa Cruz), and histone H3 (Cell Signaling). The promoter sequence corresponding to the RPL30 promoter with TCF-4 and β-catenin antibodies was used as a negative control because there is no TCf-4 or β-catenin DNA binding site in the region amplified. Additional negative controls included rabbit IgG and no DNA (no template). The gel shows total input DNA compared to DNA immunoprecipitated with the antibodies as noted. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were performed at least three times; results represent the mean +/− the standard deviation from the repeat experiments. The gel shown is taken from a representative experiment.

Table 2.

EMSA Oligonucleotide Sequencesa

| Biotinylated TBE1 | 5′-/5Biosg/TTCCCTCGAAAGTTGGAAGCAGC-3′ |

| Unlabeled TBE1 | 5′-TTCCCTCGAAAGTTGGAAGCAGC-3′ |

| Biotinylated mTBE1 | 5′-/5Biosg/TTCCCTCGgagGTTGGAAGCAGC-3′ |

| Biotinylated TBE2A | 5′-/5Biosg/GTTCATTAATTGTACCCCAAG-3′ |

| Unlabeled TBE2A | 5′-GTTCATTAATTGTACCCCAAG-3′ |

| Biotinylated TBE2B | 5′-/5Biosg/CTTGGGGTACAATTAATGAAC-3′ |

| Biotinylated mTBE2B | 5′-/5Biosg/CTTGGGGTACAgtcAATGAAC-3′ |

| Unlabeled TBE2B | 5′-CTTGGGGTACAATTAATGAAC-3′ |

| Nonspecific (HMGA1 coding region) | 5′-GTGGCCTGCCCGCGCCTCGTCTCT-3′ |

Italics indicate nucleotide changes

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least three independent experiments. For the real-time PCR analysis, each independent experiment was performed in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined by a one- or two-tailed student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism computer software.

RESULTS

Wild-type APC represses HMGA1 expression

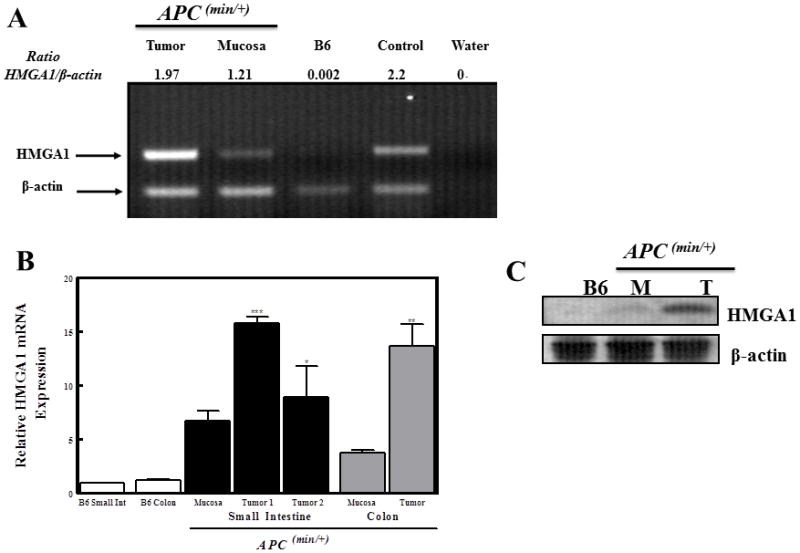

The Wnt signaling pathway genes (APC, TCF-4, and β-catenin) and HMGA1 all have well-established links to the transformed phenotype in colon cancer cells. Therefore, we analyzed HMGA1 expression in APCMin/+ mice carrying a germline heterozygous mutation at codon 850 resulting in a carboxyterminal truncation and hyperactivation of TCF-/β-catenin activity. 65, 67 These mice are predisposed to multiple intestinal polyps that preferentially develop in the distal region of the small intestine and in the colon. 65 Total RNA was isolated from the mucosa and tumors in the small intestine and colon of APCMin/+ mice and from the intestinal mucosa of normal mice for semiquantitative RT-PCR and quantitative real time PCR. Semiquantitative RT-PCR showed elevated HMGA1 mRNA levels in adenomas from both intestinal mucosa (1.21-fold greater than β-actin) and tumors of APCMin/+ mice (1.97-fold greater than β-actin) (Fig 1a). In contrast, there was no detectable expression of HMGA1 mRNA in normal intestinal mucosa of normal C57B6 mice expressing wt-APC. This finding was further confirmed by quantitative real-time reverse transcription in which increases in HMGA1 mRNA from APCMin/+ intestinal tumors (first set of mice 15.76±1.08; second set of mice 8.9±5.08) and non-tumorous intestinal mucosa (6.75±1.57) of APCMin/+ mice were higher than normal mice (Fig 1b). To further validate expression, we conducted immunoblot analysis of extracts prepared from tumor tissues or scrapings of intestinal mucosa. Consistent with the mRNA levels, HMGA1 proteins were present at high levels in the intestinal mucosa of APCMin/+ mice and the extent of upregulation was more pronounced in intestinal tumors (Fig 1c). In the colons of APCMin/+ mice (Fig 1b), HMGA1 mRNA from colon mucosa and tumors were about 4 (3.73 ± 0.25) and 14-fold (13.67 ± 2.03) higher than C57B6 mice, respectively.

Figure 1. HMGA1 expression is upregulated in the intestinal compartment of APCMin/+ mice.

(A) Semiquantitative RT-PCR shows that small intestinal mucosa and tumors isolated from mice bearing a truncated APC gene (APCMin/+) have a significant increase in HMGA1 mRNA compared to control C57B6 (B6) mice. β-actin was used as an internal control for all samples and the positive control (labeled control in this figure) was RNA isolated from the splenocytes of HMGA1 transgenic mice.

(B) HMGA1 mRNA levels were confirmed in both the small and large intestinal tissues using quantitative real-time RT-PCR with primers and probes specific for murine HMGA1. ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05 relative to tissues from the small intestine of B6 mice (n=4).

(C) Tissues from the small intestinal mucosa (M) and tumors (T) from these mice also have increased HMGA1 protein compared to analogous tissues from control (B6) mice as determined by western blot analysis.

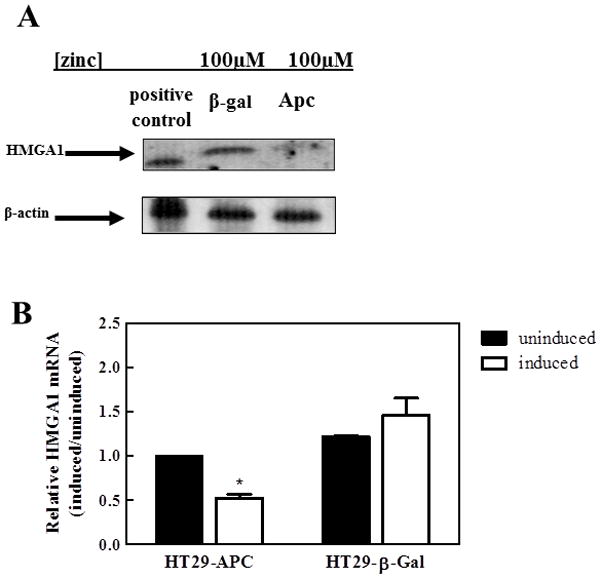

We then tested whether recovery of APC function could downregulate HMGA1. To this aim, we used HT-29 colonic cancer cells harboring a Zn-inducible transgene encoding wt-APC 64 thus allowing us to evaluate whether the presence of this tumor suppressor activity silences HMGA1 expression. Cells were induced with 100 μM Zn and the levels of HMGA1 mRNA and protein measured using quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2, expression of HMGA1 was significantly reduced both at the mRNA (to ~50%; p<0.01) and protein (to ~85% reduction after 72 hours) level following reconstitution of wild-type APC. However, Zn-induced expression of β-galactosidase instead of APC did not impact HMGA1 expression (p=0.277). From these data, we concluded that APC negatively regulates HMGA1 expression.

Figure 2. Recovery of full length APC downregulates HMGA1 expression in HT29 cells.

(A) HT29 cells bearing truncated APC were transfected so that full-length APC could be induced by the pSAR-MT vector when exposed to 100 μM zinc.22 β-galactosidase (control; HT29-β-Gal) and APC inducible HT29 (HT29-APC) cells were treated with 100 μM zinc for 72 hours, the protein was isolated, and HMGA1 expression determined by western blot. HT29-Apc cells treated with zinc displayed decreased expression of HMGA1 when compared to the HT29 β-galactosidase control. The western shows a representative image of three independent experiments.

(B) HMGA1 mRNA levels were confirmed using quantitative real-time RT-PCR with primers and probes specific for human HMGA1. *p<0.05 relative to untreated HT29-APC. Data shown represent the mean +/− the standard deviation from three independent experiments that were conducted in triplicate.

TCF-4 binds to the human HMGA1 promoter in vitro and in vivo

Direct activation of APC/β-catenin/TCF-4 target genes by the TCF-4/β-catenin complex requires the presence of one or more TCF-4 binding sites within the promoter of the putative target. 68 To evaluate whether APC dysfunction upregulates HMGA1 through activity of the β-catenin/TCF-4 complex, we conducted in silico analysis of the human HMGA1 promoter sequence 66 searching for putative TCF-4 binding elements (TBE) that match the consensus, 5′-(A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G-3′)69 and found two potential matches within the first 1500bp upstream of the transcription start sites (Fig 3A).66 These putative binding sites were highly conserved between human and mouse. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were used to test whether the HMGA1 TBEs were occupied by TCF-4 and β-catenin in HCT116 cells (with substantial upregulation) bearing constitutively active β-catenin. 70 We designed two pairs of PCR primers so that the first corresponded to the first potential site (TBE1; spanning −487 bp to −801 bp of the promoter) and the second encompassed two sites (TEB2A and TBE 2B; spanning −1247 bp to −1599 bp of the promoter) (Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3b, fragments corresponding to the respective TBEs could be detected when 2% of the native, unprecipitated chromatin (labeled INPUT) verifying the integrity of each sample prior to immunoprecipitation. Moreover, TCF-4 and β-catenin, but not IgG, were capable of occupying the HMGA1 promoter in vivo evidenced by the presence of HMGA1 amplicons corresponding to TBE1 and TBE2 (Fig. 3b). Specificity of this interaction was further confirmed by the lack of amplification products in reactions lacking antibody or using RPL-30 specific primers (Fig 3b). The results of the ChIP assays demonstrate that the TCF-4/β-catenin complex binds HMGA1 promoter DNA in vivo and supports the expression correlation studies observed in mouse tissues and HT29 cells.

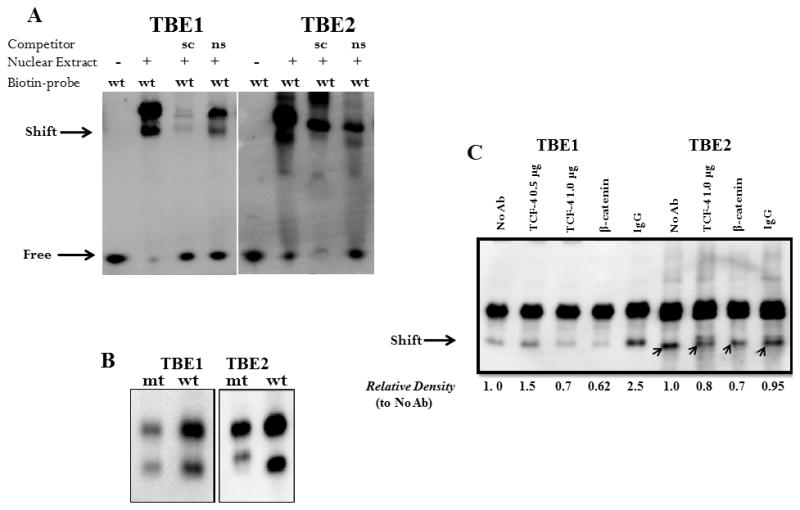

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were then used to further confirm the ability of this transcription factor complex to occupy the HMGA1 TBE sites in vitro. Biotinylated probes duplicating TBE1 and TBE2B, and not TBE2A (data not shown) generated a robust protein-DNA complex in the presence of HCT116 nuclear extracts (Fig. 4a). We therefore refer the probe duplicating TBE2B as TBE2. Formation of these protein-DNA complexes was abrogated by the addition of a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled probes corresponding to the same region but not by an unrelated sequence within the HMGA1 coding region. The formation of protein-DNA complexes was sequence specific since biotin-labeled TBE1 and TBE2 probes bearing mutations in the TCF-4 binding region displayed marked repression of binding (Fig. 4b) when compared to those harboring the TCF-4 consensus. To confirm the presence of TCF-4 and β-catenin in the protein-DNA complexes, we carried out supershift assays using antibodies raised against the respective proteins (Fig. 4C). The presence of the TCF-4 antibody, but not IgG, diminished the abundance of the protein-DNA complex in a dose dependent manner for probes duplicating regions corresponding to TBE1 and TBE2 of the HMGA1 promoter.71 Similar results were obtained in studies using the β-catenin antibody. Because both TCF-4 and β-catenin were able to form nuclear complexes at the TCF-4 binding sites, we concluded that β-catenin interacts with TCF-4 at TBE1 (beginning at −638bp) and TBE2 (beginning at −1290bp) of the HMGA1 promoter in vivo and in vitro.

Figure 4. β-catenin/TCF-4 complexes in nuclear extracts from HCT 116 cells binds the HMGA1 promoter in vitro.

Nuclear extracts were isolated from HCT116 cells and incubated with 50 fmol biotinylated DNA probe corresponding to the human HMGA1 promoter sequences beginning at −638bp (TBE1) and −1290 (TBE2) from the transcriptional initiation sequence.

(A) Protein-DNA complexes were detected for biotin-labeled TBE1 and TBE2. For binding competition, a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled DNA probe corresponding to TBE1 and TBE2 sequences was included in the reactions to serve as a specific competitor probe (sc). Unlabeled oligonucleotides bearing irrelevant sequences within the HMGA1 coding region served as non-specific competitor probe (ns).

(B) Mutant (mt) biotin-labeled TBE1 and TBE2 oligonucleotides were incubated with nuclear extracts from HCT116 cells and their relative interactions compared to biotinylated wild-type (wt) oligonucleotides. Results shown are representative of three independent gel retardation assays.

(C) For supershift assays, TCF-4, β-catenin, or control rabbit IgG was included. The arrows indicate the position of the specific transcription factor complexes and values below each lane reflect the relative band density compared to oligo and extracts in the absence of antibodies. Results shown are representative of four independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Aberrant expression of HMGA1 proteins has been documented in several tumor types and its causal role in oncogenesis has been demonstrated using a number of experimental models. 31, 36, 37, 39–42, 49, 72 Despite the tremendous attention to understanding the mechanisms by which HMGA1 confers malignancy, the processes governing gene activation are not clearly understood. The present study explored the hypothesis that Hmga1expression is regulated by Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling in colon cancer cells. Our data indicate that APC mutations are indeed capable of inducing HMGA1 expression using the β-catenin/TCF-4 axis as a transcriptional switch.

It is well established that mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor gene are responsible for the earliest stages of colorectal tumorigenesis. 6, 7, 11, 13, 15, 73 Similarly, we show that high levels of HMGA1 mRNA and protein are present in gastrointestinal tissues of APCMin/+ mice and that recovery of APC function in HT-29 cells represses HMGA1 mRNA and protein levels. This finding aligns with the seminal finding by Fedele et al. citing HMGA1 upregulation in colorectal cancers 45, 46 and in more recent work identifying HMGA1 as a key switch for cancer initiation in colorectal tissues. 47 In fact, HMGA1 expression is one of only four genes of the colorectal transcriptome to be significantly altered when compared to normal epithelium making an essential component of the colorectal cancer genetic signature. 44, 47 Also, transgenic mice overexpressing HMGA1 develop intestinal polyposis 57, a trait similar to that seen in mice carrying APC mutations. 65 Not surprisingly, mutations in APC and β-catenin are common genetic signatures of human tumors that also have increased levels of HMGA1. It is also worth mentioning that when HMGA1 is inhibited in colorectal and other cancer cells, tumor formation and metastatic progression are abrogated. 47, 74–76 Thus, restoration of APC function could serve as a genetic mode of downregulating HMGA1.

APC function is loss early in colonic carcinogenesis and our data suggests that HMGA1 levels are also increased early in the process. Moreover, our studies showed induction of HMGA1 expression at the transcriptional level. Based on this and on the involvement of both β-catenin and HMGA1 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) 41, 57, we explored the potential activation of HMGA1 by the TCF-4/β-catenin transcriptional complex. We confirmed the binding of this complex at two TCF-4 binding elements within the HMGA1 promoter region demonstrating that APC regulates HMGA1 expression in human colon cancer cells via induction of the β-catenin/TCF-4 complex. This complex also activates transcription of c-myc 21, 22, a known transcriptional activator of HMGA1. 40 This raised the possibility that HMGA1 activation by the Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 pathway in our study could be secondary to c-myc induction. Akaboshi and coworkers recently reported correlations between HMGA1 and β-catenin gastric tissue upon knockdown of c-myc.77 Our current findings in colon cancer support this link between the two pathways. In contrast to observations in gastric cancer cells, our evidence that the functional TCF-4 binding site with the HMGA1 promoter suggests a mechanism for direct, myc-independent, activation of HMGA1 transcription by TCF-4/β-catenin. Interestingly,

In summary, our findings implicate aberrant Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling in driving the oncogenic expression of HMGA1. Our study has important implications in the role played by HMGA1 in the proliferation, growth, and survival of both traditional colon cancer cells and colon cancer stem cells. While the importance of Wnt signaling deregulation is widely accepted, therapies targeting this pathway have yielded limited success to date. Given the oncogenic activity of HMGA1 and its requirement for initiating and maintaining colorectal tumors, these findings shed light on an additional pathway by which the gene is activated. It is possible that the molecular cross-talk between tumor suppressors and oncogenes can be exploited in targeted therapies against colon cancer.

Table 1.

ChIP-PCR Primer Sequences

| TBE1 Forward | 5′-GAAAGTTGGAAGCAGCAGAG-3′ |

| TBE1 Reverse | 5′-CACAGGATGTGTATGCTCAGCT-3′ |

| TBE2 Forward | 5′-CCCTTGGTCCAAGTTTCAAGAGTG-3′ |

| TBE2 Reverse | 5′-CCAAATAACTCTCTACTCACTGACCC-3′ |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (1R15CA137520-01), National Center for Research Resources (5 P20 RR016461), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P20 GM103499) of the National Institutes for Health, the National Science Foundation (MCB0542242) with partial student support (RAN and ATB) from the Winthrop McNair Scholars program. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Frank G. Berger and Mrs. Tia Davis (University of South Carolina Department of Biology) for mouse tissue samples, Drs. Ken Kinzler and Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) for inducible HT29 cell lines, and members of the Sumter lab for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fulda S. Tumor resistance to apoptosis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(3):511–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blagosklonny MV. Molecular theory of cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4(6):621–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.6.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finlay GJ. Genetics, molecular biology and colorectal cancer. Mutat Res. 1993;290(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90027-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowan AJ, Lamlum H, Ilyas M, Wheeler J, Straub J, Papadopoulou A, Bicknell D, Bodmer WF, Tomlinson IP. APC mutations in sporadic colorectal tumors: A mutational “hotspot” and interdependence of the “two hits”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(7):3352–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamlum H, Papadopoulou A, Ilyas M, Rowan A, Gillet C, Hanby A, Talbot I, Bodmer W, Tomlinson I. APC mutations are sufficient for the growth of early colorectal adenomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(5):2225–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040564697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamlum H, Ilyas M, Rowan A, Clark S, Johnson V, Bell J, Frayling I, Efstathiou J, Pack K, Payne S, Roylance R, Gorman P, Sheer D, Neale K, Phillips R, Talbot I, Bodmer W, Tomlinson I. The type of somatic mutation at APC in familial adenomatous polyposis is determined by the site of the germline mutation: a new facet to Knudson’s ‘two-hit’ hypothesis. Nat Med. 1999;5(9):1071–5. doi: 10.1038/12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joslyn G, Carlson M, Thliveris A, Albertsen H, Gelbert L, Samowitz W, Groden J, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M, et al. Identification of deletion mutations and three new genes at the familial polyposis locus. Cell. 1991;66(3):601–13. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, Carlson M, Gelbert L, Albertsen H, Joslyn G, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M, et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66(3):589–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodmer WF, Cottrell S, Frischauf AM, Kerr IB, Murday VA, Rowan AJ, Smith MF, Solomon E, Thomas H, Varesco L. Genetic analysis of colorectal cancer. Princess Takamatsu Symp. 1989;20:49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneikert J, Behrens J. The canonical Wnt signalling pathway and its APC partner in colon cancer development. Gut. 2007;56(3):417–25. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.093310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparks AB, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Mutational analysis of the APC/beta-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58(6):1130–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science. 1997;275(5307):1787–90. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilyas M, Tomlinson IP, Rowan A, Pignatelli M, Bodmer WF. Beta-catenin mutations in cell lines established from human colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(19):10330–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Embo J. 1997;16(13):3797–804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubinfeld B, Albert I, Porfiri E, Fiol C, Munemitsu S, Polakis P. Binding of GSK3beta to the APC-beta-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly. Science. 1996;272(5264):1023–6. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munemitsu S, Albert I, Souza B, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(7):3046–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinfeld B, Souza B, Albert I, Muller O, Chamberlain SH, Masiarz FR, Munemitsu S, Polakis P. Association of the APC gene product with beta-catenin. Science. 1993;262(5140):1731–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8259518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korinek V, Barker N, Morin PJ, van Wichen D, de Weger R, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Clevers H. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC−/− colon carcinoma. Science. 1997;275(5307):1784–7. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myant K, Sansom OJ. Wnt/Myc interactions in intestinal cancer: partners in crime. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317(19):2725–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281(5382):1509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araki Y, Okamura S, Hussain SP, Nagashima M, He P, Shiseki M, Miura K, Harris CC. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression by the Wnt and ras pathways. Cancer Res. 2003;63(3):728–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conacci-Sorrell ME, Ben-Yedidia T, Shtutman M, Feinstein E, Einat P, Ben-Ze’ev A. Nr-CAM is a target gene of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway in melanoma and colon cancer and its expression enhances motility and confers tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16(16):2058–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.227502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz DR, Wu R, Kardia SL, Levin AM, Huang CC, Shedden KA, Kuick R, Misek DE, Hanash SM, Taylor JM, Reed H, Hendrix N, Zhai Y, Fearon ER, Cho KR. Novel candidate targets of beta-catenin/T-cell factor signaling identified by gene expression profiling of ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63(11):2913–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeilstra J, Joosten SP, Dokter M, Verwiel E, Spaargaren M, Pals ST. Deletion of the WNT target and cancer stem cell marker CD44 in Apc(Min/+) mice attenuates intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68(10):3655–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Li J, Chen B. Oct4 was a novel target of Wnt signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;362(1–2):233–40. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1148-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valencia J, Hernandez-Lopez C, Martinez VG, Hidalgo L, Zapata AG, Vicente A, Varas A, Sacedon R. Transient beta-catenin stabilization modifies lineage output from human thymic CD34+CD1a− progenitors. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87(3):405–14. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0509344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan S, Zhou C, Zhang W, Zhang G, Zhao X, Yang S, Wang Y, Lu N, Zhu H, Xu N. beta-Catenin/TCF pathway upregulates STAT3 expression in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2008;271(1):85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mann B, Gelos M, Siedow A, Hanski ML, Gratchev A, Ilyas M, Bodmer WF, Moyer MP, Riecken EO, Buhr HJ, Hanski C. Target genes of beta-catenin-T cell-factor/lymphoid-enhancer-factor signaling in human colorectal carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(4):1603–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fedele M, Fusco A. HMGA and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799(1–2):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yie J, Liang S, Merika M, Thanos D. Intra- and intermolecular cooperative binding of high-mobility-group protein I(Y) to the beta-interferon promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(7):3649–62. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleynen I, Van de Ven WJ. The HMGA proteins: A myriad of functions (Review) Int J Oncol. 2008;32(2):289–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves R, Beckerbauer L. HMGI/Y proteins: flexible regulators of transcription and chromatin structure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1519(1–2):13–29. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans A, Lennard TW, Davies BR. High-mobility group protein 1(Y): metastasis-associated or metastasis-inducing? J Surg Oncol. 2004;88(2):86–99. doi: 10.1002/jso.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resar LM. The high mobility group A1 gene: transforming inflammatory signals into cancer? Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):436–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sumter TF. An emerging role for HMGA1a in human cancer & disease. Current Molecular Medicine. 2012 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarhadi VK, Wikman H, Salmenkivi K, Kuosma E, Sioris T, Salo J, Karjalainen A, Knuutila S, Anttila S. Increased expression of high mobility group A proteins in lung cancer. J Pathol. 2006;209(2):206–12. doi: 10.1002/path.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood LJ, Maher JF, Bunton TE, Resar LM. The oncogenic properties of the HMG-I gene family. Cancer Res. 2000;60(15):4256–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood LJ, Mukherjee M, Dolde CE, Xu Y, Maher JF, Bunton TE, Williams JB, Resar LM. HMG-I/Y, a new c-Myc target gene and potential oncogene. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(15):5490–502. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5490-5502.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reeves R, Edberg DD, Li Y. Architectural transcription factor HMGI(Y) promotes tumor progression and mesenchymal transition of human epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(2):575–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.575-594.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Y, Sumter TF, Bhattacharya R, Tesfaye A, Fuchs EJ, Wood LJ, Huso DL, Resar LM. The HMG-I oncogene causes highly penetrant, aggressive lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice and is overexpressed in human leukemia. Cancer Res. 2004;64(10):3371–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cleynen I, Huysmans C, Sasazuki T, Shirasawa S, Van de Ven W, Peeters K. Transcriptional control of the human high mobility group A1 gene: Basal and oncogenic ras-regulated expression. Cancer Res. 2007;67(10):4620–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grade M, Hormann P, Becker S, Hummon AB, Wangsa D, Varma S, Simon R, Liersch T, Becker H, Difilippantonio MJ, Ghadimi BM, Ried T. Gene expression profiling reveals a massive, aneuploidy-dependent transcriptional deregulation and distinct differences between lymph node-negative and lymph node-positive colon carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2007;67(1):41–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim DH, Park YS, Park CJ, Son KC, Nam ES, Shin HS, Ryu JW, Kim DS, Park CK, Park YE. Expression of the HMGI(Y) gene in human colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;84(4):376–80. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990820)84:4<376::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fedele M, Bandiera A, Chiappetta G, Battista S, Viglietto G, Manfioletti G, Casamassimi A, Santoro M, Giancotti V, Fusco A. Human colorectal carcinomas express high levels of high mobility group HMGI(Y) proteins. Cancer Res. 1996;56(8):1896–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grade M, Hummon AB, Camps J, Emons G, Spitzner M, Gaedcke J, Hoermann P, Ebner R, Becker H, Difilippantonio MJ, Ghadimi BM, Beissbarth T, Caplen NJ, Ried T. A genomic strategy for the functional validation of colorectal cancer genes identifies potential therapeutic targets. Int J Cancer. 2010;128(5):1069–79. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Zee JA, ten Hagen TL, Hop WC, van Dekken H, Dicheva BM, Seynhaeve AL, Koning GA, Eggermont AM, van Eijck CH. Differential expression and prognostic value of HMGA1 in pancreatic head and periampullary cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(18):3393–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahman MM, Qian ZR, Wang EL, Sultana R, Kudo E, Nakasono M, Hayashi T, Kakiuchi S, Sano T. Frequent overexpression of HMGA1 and 2 in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours and its relationship to let-7 downregulation. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(3):501–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tesfaye A, Di Cello F, Hillion J, Ronnett BM, Elbahloul O, Ashfaq R, Dhara S, Prochownik E, Tworkoski K, Reeves R, Roden R, Ellenson LH, Huso DL, Resar LM. The high-mobility group A1 gene up-regulates cyclooxygenase 2 expression in uterine tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):3998–4004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pierantoni GM, Agosti V, Fedele M, Bond H, Caliendo I, Chiappetta G, Lo Coco F, Pane F, Turco MC, Morrone G, Venuta S, Fusco A. High-mobility group A1 proteins are overexpressed in human leukaemias. Biochem J. 2003;372(Pt 1):145–50. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tallini G, Dal Cin P. HMGI(Y) and HMGI-C dysregulation: a common occurrence in human tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6(5):237–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bandiera A, Bonifacio D, Manfioletti G, Mantovani F, Rustighi A, Zanconati F, Fusco A, Di Bonito L, Giancotti V. Expression of HMGI(Y) proteins in squamous intraepithelial and invasive lesions of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 1998;58(3):426–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang ML, Chen CC, Chang LC. Gene expressions of HMGI-C and HMGI(Y) are associated with stage and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24(11):1281–6. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0770-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang EL, Qian ZR, Rahman MM, Yoshimoto K, Yamada S, Kudo E, Sano T. Increased expression of HMGA1 correlates with tumour invasiveness and proliferation in human pituitary adenomas. Histopathology. 2010;56(4):501–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flohr AM, Rogalla P, Bonk U, Puettmann B, Buerger H, Gohla G, Packeisen J, Wosniok W, Loeschke S, Bullerdiek J. High mobility group protein HMGA1 expression in breast cancer reveals a positive correlation with tumour grade. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18(4):999–1004. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belton A, Gabrovsky A, Bae YK, Reeves R, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Huso DL, Resar LM. HMGA1 induces intestinal polyposis in transgenic mice and drives tumor progression and stem cell properties in colon cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hommura F, Katabami M, Leaner VD, Donninger H, Sumter TF, Resar LM, Birrer MJ. HMG-I/Y is a c-Jun/activator protein-1 target gene and is necessary for c-Jun-induced anchorage-independent growth in Rat1a cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2(5):305–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dhar A, Hu J, Reeves R, Resar LM, Colburn NH. Dominant-negative c-Jun (TAM67) target genes: HMGA1 is required for tumor promoter-induced transformation. Oncogene. 2004;23(25):4466–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nateri AS, Spencer-Dene B, Behrens A. Interaction of phosphorylated c-Jun with TCF4 regulates intestinal cancer development. Nature. 2005;437(7056):281–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hillion J, Dhara S, Sumter TF, Mukherjee M, Di Cello F, Belton A, Turkson J, Jaganathan S, Cheng L, Ye Z, Jove R, Aplan P, Lin YW, Wertzler K, Reeves R, Elbahlouh O, Kowalski J, Bhattacharya R, Resar LM. The high-mobility group A1a/signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 axis: an achilles heel for hematopoietic malignancies? Cancer Res. 2008;68(24):10121–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinez Hoyos J, Fedele M, Battista S, Pentimalli F, Kruhoffer M, Arra C, Orntoft TF, Croce CM, Fusco A. Identification of the genes up- and down-regulated by the high mobility group A1 (HMGA1) proteins: tissue specificity of the HMGA1-dependent gene regulation. Cancer Res. 2004;64(16):5728–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Foster LC, Wiesel P, Huggins GS, Panares R, Chin MT, Pellacani A, Perrella MA. Role of activating protein-1 and high mobility group-I(Y) protein in the induction of CD44 gene expression by interleukin-1beta in vascular smooth muscle cells. Faseb J. 2000;14(2):368–78. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Apoptosis and APC in colorectal tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(15):7950–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, Gould KA, Dove WF. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256(5057):668–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pedulla ML, Treff NR, Resar LM, Reeves R. Sequence and analysis of the murine Hmgiy (Hmga1) gene locus. Gene. 2001;271(1):51–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00500-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luongo C, Gould KA, Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Dietrich W, Lander ES, Moser AR. Mapping of multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) to proximal chromosome 18 of the mouse. Genomics. 1993;15(1):3–8. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kuhl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382(6592):638–42. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wehkamp J, Wang G, Kubler I, Nuding S, Gregorieff A, Schnabel A, Kays RJ, Fellermann K, Burk O, Schwab M, Clevers H, Bevins CL, Stange EF. The Paneth cell alpha-defensin deficiency of ileal Crohn’s disease is linked to Wnt/Tcf-4. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):3109–18. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sekine S, Shibata T, Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S. Target disruption of the mutant beta-catenin gene in colon cancer cell line HCT116: preservation of its malignant phenotype. Oncogene. 2002;21(38):5906–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu J, Richards MH, Huang J, Al-Harthi L, Xu X, Lin R, Xie F, Gibson AW, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP. Human FasL gene is a target of beta-catenin/T-cell factor pathway and complex FasL haplotypes alter promoter functions. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hristov AC, Cope L, Di Cello F, Reyes MD, Singh M, Hillion JA, Belton A, Joseph B, Schuldenfrei A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Resar LM. HMGA1 correlates with advanced tumor grade and decreased survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(1):98–104. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murphy JT, Tucker JM, Davis C, Berger FG. Raltitrexed increases tumorigenesis as a single agent yet exhibits anti-tumor synergy with 5-fluorouracil in ApcMin/+ mice. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3(11):1169–76. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.11.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dolde CE, Mukherjee M, Cho C, Resar LM. HMG-I/Y in human breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;71(3):181–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1014444114804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berlingieri MT, Pierantoni GM, Giancotti V, Santoro M, Fusco A. Thyroid cell transformation requires the expression of the HMGA1 proteins. Oncogene. 2002;21(19):2971–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scala S, Portella G, Fedele M, Chiappetta G, Fusco A. Adenovirus-mediated suppression of HMGI(Y) protein synthesis as potential therapy of human malignant neoplasias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(8):4256–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070029997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Akaboshi S, Watanabe S, Hino Y, Sekita Y, Xi Y, Araki K, Yamamura K, Oshima M, Ito T, Baba H, Nakao M. HMGA1 is induced by Wnt/beta-catenin pathway and maintains cell proliferation in gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(4):1675–85. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]