Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

To examine the cultural beliefs and attitudes of African American prostate cancer survivors regarding the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities.

Research Approach

Mixed methods with primary emphasis on a phenomenology approach.

Setting

In-person interviews in participants’ homes and rural community facilities.

Participants

14 African American men diagnosed with and treated for prostate cancer.

Methodologic Approach

Personal interviews using a semistructured interview guide.

Main Research Variables

Prostate cancer, CAM, African American men’s health, culture, herbs, prayer, spirituality, and trust.

Findings

All participants used prayer often; two men used meditation and herbal preparations. All men reported holding certain beliefs about different categories of CAM. Several men were skeptical of CAM modalities other than prayer. Four themes were revealed: importance of spiritual needs as a CAM modality to health, the value of education in relation to CAM, importance of trust in selected healthcare providers, and how men decide on what to believe about CAM modalities.

Conclusions

Prayer was a highly valued CAM modality among African American prostate cancer survivors as a way to cope with their disease. Medical treatment and trust in healthcare providers also were found to be important.

Interpretation

Most participants were skeptical of CAM modalities other than prayer. Participants expressed a strong belief in spirituality and religiosity in relationship to health and their prostate cancer. Participants’ trust in their healthcare providers was important. Healthcare providers must understand how African Americans decide what to believe about CAM modalities to improve their health. This research provided valuable information for future development of culturally sensitive communication and infrastructural improvements in the healthcare system.

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in the United States. The American Cancer Society (2007) estimated that in 2007, 218,890 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States and approximately 27,050 men will die from the disease, making it the second leading cause of cancer death among all men. The age-adjusted incidence of prostate cancer from 1998–2002 was 272 per 100,000 among African Americans compared to 169 per 100,000 among Caucasians (Ries et al., 2006). Furthermore, prostate cancer mortality rates in African Americans are at least two times higher than in Caucasians (American Cancer Society; Ries et al.). Prostate cancer affects African American men disproportionately, especially when compared to Caucasians.

Reasons for increased prostate cancer incidence and mortality among African American men are unclear. Distrust of the medical system, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) beliefs, poverty, limited education, and prior health experiences contribute to existing disparities in mortality rates (Agho & Lewis, 2001; Farkas, Marcella, & Rhoads, 2000; Jones & Wenzel, 2005; Kendall & Hatton, 2002; Kinney, Emery, Dudley, & Croyle, 2002; Marks, 2002; Wolff et al., 2003). Many African Americans continue to distrust healthcare providers because of prior and continuing unequal healthcare experiences. The infamous Tuskegee syphilis study (conducted from 1932–1972), in which African American men with syphilis were denied treatment, is still cited as a reason for wariness of conventional health care in the United States (Weinrich et al., 2002). Several studies suggest that CAM modalities, including cultural and religious beliefs, may be one of the most significant contributors to unequal mortality for African Americans with cancer (Kinney et al.; Lannin et al., 1998; Margolis et al., 2003). The official definition from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine ([NCCAM], 2007), an institute of the National Institutes of Health, identifies CAM as a group of products and practices that are not considered part of conventional allopathic treatments. NCCAM classifies prayer and spirituality as CAM modalities. For purposes of this research, the authors have used NCCAM’s definition of CAM. The focus of the research is on the exploration of CAM modality use and beliefs among African American survivors of prostate cancer.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Prostate Cancer

Although few studies have examined CAM use among men diagnosed with prostate cancer, even less information is available on CAM use among African American men with prostate cancer. Some evidence suggests that minority patients (African American, Hispanic, and Asian) are more likely to begin CAM use after being diagnosed with prostate cancer than before diagnosis (Diefenbach et al., 2003). The most common CAM treatments that the men reported using were herbal or dietary therapies (e.g., saw palmetto) and mind-body techniques (e.g., prayer). Hall, Bissonette, Boyd, and Theodorescu (2003) reported that the most common reasons that men with prostate cancer used CAM were that it made them feel better and that they believed that CAM may help cure their cancer. In another study, African Americans and other minority survivors of prostate cancer reported using herbal remedies and forms of counseling most often (Lee, Chang, Jacobs, & Wrensch, 2002).

Few studies have examined the beliefs and experiences of African American men in regard to how prostate cancer and treatments affect individuals diagnosed with the disease. Thus, a study that focused on CAM use among African American men diagnosed with prostate cancer was an important step toward understanding this vulnerable population.

Methods

As part of a larger study that focused on the development of culturally competent prostate cancer terms for rural African American men of lower socioeconomic status, the present study explored the beliefs and attitudes of African American survivors of prostate cancer regarding the use of CAM. A mixed methods design using qualitative and quantitative techniques was selected to produce a broad view with specific and rich descriptions of participants’ experiences with the use of CAM for prostate cancer (Creswell, 2003).

The qualitative method used was phenomenologic (Cohen, Kahn, & Steeves, 2000). This method is appropriate for exploring, interpreting, and describing areas of experience that are complex and not explored fully already. The method can be explained best through heuristic interpretation of text in context. That is, the participants are encouraged to relay their experiences in narrative form and explain the settings in which events happened as well as the culturally determined meanings that they find in their experiences. Thus, the interviewer asked participants to talk about their use of CAM and when, how, and why they used a particular product or practice. Data from the narratives first were examined within subjects to describe the decisions and experiences of each person. Then the data were examined across participants to group and categorize similar ideas, beliefs, and choices. The final product was an interpretation and description of the experiences of all of the participants who talked about using CAM.

Sample, Setting, and Procedure

Fourteen participants were recruited for the study. Five were from a prostate cancer center in central Virginia, and nine men were referred by other participants. Participants had to meet the following criteria: (a) aged 18 years or older, (b) African American race, (c) completed treatment for prostate cancer, (d) able to provide informed consent, and (e) willing to talk about attitudes and beliefs regarding CAM and allopathic medicine.

Saturation of the data was reached at the 14th participant (Creswell, 2003). One-on-one interviews with each of the 14 participants were conducted by the primary author in a clinic meeting room, a participant’s home, or another nonintimidating setting for the convenience of each study participant. The primary interviewer was an African American man who was knowledgeable about the interviewees’ ethnic background.

The interviewer used a semistructured interview guide containing a series of open-ended and categorical questions to elicit participants’ views and attitudes. Interview questions revolved around healthcare experiences of prostate cancer survivors, beliefs about alternative treatments and therapies, and the role the men believed they fulfilled in the family. The University of Virginia Health System Institutional Review Board approved the interview guide. After the primary author obtained informed consent from each study participant, he tape-recorded each interview and compiled field notes. Interviews typically lasted 1–1.5 hours. The interviewer paid close attention to the verbal and nonverbal cues of the study participants. The digital sound files from each interview were transcribed later using Transana 2.0 (Wisconsin Center for Education Research, Madison, WI). Each participant received a check for $20 to offset travel costs associated with participating in the interview.

Results

Demographics

The sample of 14 African American prostate cancer survivors had a broad range of demographic characteristics. Their ages ranged from 51–83 years; nine were married, three were widowed, and two were single. The participants’ years of education ranged from 6–17 years, and household yearly income ranged from $10,800–$70,000. Thirteen of the participants reported that they were part of the Baptist denomination, whereas one participant considered himself a Presbyterian. All of the participants had private health insurance, seven had Medicare, and five had Medicaid. The majority of the sample was retired (n = 10), and four continued full-time work.

Eight participants had a family history of prostate cancer, including diagnoses in fathers, uncles, or brothers. Half of the participants (n = 7) in the study chose to have radical prostatectomy as their primary treatment. The second most-common form of treatment (n = 3, 21%) was brachytherapy with radiation seed implants. The remaining participants were treated with leuprolide (n = 1, 7%), external beam radiation therapy (n = 1, 7%), radiation seeds and leuprolide (n = 1, 7%), or a combination of a prostatectomy and leuprolide (n = 1, 7%).

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use

All of the participants used prayer as a coping mechanism during their treatment for prostate cancer. Two of the participants used additional CAM: One used meditation, and one used herbs to help cope with the side effects of the medical treatment for prostate cancer. Although only two participants used CAM other than prayer, the men reported that they had certain beliefs about different types of CAM. The men who indicated that they did not know whether a particular CAM worked or was effective knew of the existence of that CAM but did not know whether it would have helped prevent their cancer. Five men (36%) believed that herbs would help treat prostate cancer, three (21%) believed that herbs would not help, and six (43%) reported that they did not know whether herbs would help in the treatment of prostate cancer. The majority of the men (n = 9, 64%) did not know whether removing a root (defined as summoning a curse on someone), hex, or spell would help in the treatment of prostate cancer, and five (36%) reported that they believed it would not help. The belief that chiropractic treatments do not help against prostate cancer was held by six (43%) men, whereas eight (57%) of the men reported that they did not know. Half of the men believed that spiritual or faith healing would help against prostate cancer, five (36%) believed that it would not help, and two (14%) men did not know. Many of the men (n = 6, 43%) did not know whether meditation and guided imagery would help against prostate cancer, and only three (21%) believed that they would help. Almost all of the men (n = 13, 93%) believed that prayer helps to fight against prostate cancer, although one (7%) stated that he did not know. However, all 14 of the men believed that faith in God helps in the management of prostate cancer (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Beliefs

| Helps |

Does Not Help |

Do Not Know |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complementary and Alternative Medicine | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Herbs | 5 | 36 | 3 | 21 | 6 | 43 |

| Removing a root, hex, or spell | – | – | 5 | 36 | 9 | 64 |

| Chiropractic treatments | – | – | 6 | 43 | 8 | 57 |

| Spiritual or faith healing | 7 | 50 | 5 | 36 | 2 | 14 |

| Meditation and mental imagery | 3 | 21 | 5 | 36 | 6 | 43 |

| Prayer | 13 | 93 | – | – | 1 | 7 |

| Faith in God | 14 | 100 | – | – | – | – |

N = 14

Although the majority of the men (n = 13, 93%) reported that they likely would undergo the same treatment again, many were dissatisfied with the side effects of their conventional treatments. They reported side effects that included gynecomastia, hot flashes, incontinence, diaphoresis, decreased libido, and impotence. One man reported that he would not undergo surgery again, primarily because of the pain that he experienced and the fear of having an operation.

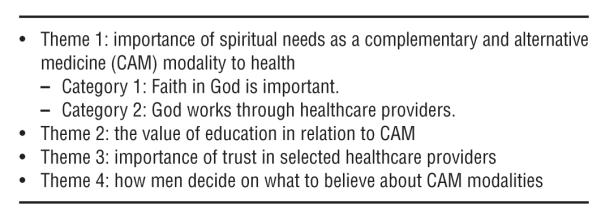

Themes Surrounding Cultural Beliefs About Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Four major themes emerged from the survivors’ experiences with prostate cancer: importance of spiritual needs as a CAM modality to health, the value of education in relation to CAM, importance of trust in selected healthcare providers, and how men decide on what to believe about CAM modalities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Themes and Categories

Importance of spiritual needs as a complementary and alternative medicine modality to health

The interviewer was able to gain information from all of the participants about their spirituality and its importance in their lives. Each participant had a unique view but with a similar underlying premise. The theme was supported by two categories: importance of faith in God, and God works through healthcare providers.

Faith in God is important

All of the men in the sample expressed the importance of faith in God. Many of the men described it as a coping mechanism. The men’s faith in God helped them in reducing the amount of stress they experienced from their prostate cancer diagnoses.

When Mr. K, a single, 59-year-old man, was asked whether he thought prayer helped a person fight cancer, he stated,

I am a person who really believes in prayer, and I think prayer really helps. I have heard people say they prayed, and prayer cured their cancer. I think prayer helps you relax and gives you peace of mind… . I don’t think it prevents or heals cancer.

When the interviewer began to explore the meaning of Mr. K’s relationship with God and his cancer treatments in more detail, he spoke about how his faith was a way of coping, stating,

I think I have a strong faith, and I think that has contributed to me dealing with it more so than anything… . In coping, peace of mind, I think my belief in God is where most of my strength comes from… . The only thing is that I have a strong faith, as I mentioned.

All of the men articulated that their faith in God and their prayers helped them cope with their diagnosis of prostate cancer.

God works through healthcare providers

All of the study participants agreed with the statement that God works through healthcare providers. They believed that God gave healthcare providers the knowledge and skills to diagnose illnesses and provide appropriate healthcare treatments. Mr. L, a 77-year-old, widowed, retired electrician, stated,

I just feel like that … God is good, he’s very good, and he helps out doctors a lot, too. I don’t give him all the credit because the doctors got to deserve some of that, too. So I can’t say God did it all by himself or whatever. I think, to me, he give doctors knowledge … and things like that. That’s the way I think about it.

Although all of the participants agreed that God worked through doctors and healthcare providers to treat their prostate cancer, they did not consider that trusting and believing solely in God would cure their cancer. Mr. K stated,

I think prayer is a treatment, and I think it helps you deal with reality and deals with things. I don’t think it really cures anything. I think that God gave us the mind, the talent, people the talent to help them to take care of those things. I don’t think it cures anything; it just helps you deal with it. I don’t think it prevents.

Although the power of faith was a universal theme in the study sample, all participants agreed that prayer by itself is not a sufficient treatment modality for prostate cancer.

The value of education in relation to complementary and alternative medicine

All of the participants stressed the importance of education as it relates to prostate cancer and CAM. The use of root doctors (people known to be versed in magical or traditional cures from plants) or folk practitioners was seen as a practice that was not scientifically proven. The practices often were viewed as being superstitious. Several survivors attributed the decrease in the belief of root and folk medicines and therapies to formal education, which was denied to their parents.

In the present sample, only two individuals had used CAM other than prayer to treat their prostate cancer. Mr. R used meditation to assist in his treatment. He stated that he used positive attitude and maintained an open mind after he was diagnosed and during treatment. To help treat his prostate cancer, Mr. Z used a mixture of herbs consolidated into tablet form. Although Mr. Z did not remember the names of the herbs, he did express that he used the herbal mixture only during the time he was diagnosed and treated, which was about one year. The majority of the sample did not believe in using other CAM modalities, besides prayer, for several reasons. Many participants believed that some CAM modalities are supernatural and superstitious, perhaps reflecting their knowledge about CAM. However, several participants revealed that their parents believed in root or folk medicines as therapies to cure or treat their illnesses. The participants suggested that they grew up around root and folk medicine, but they did not believe in using those CAM modalities now. Many believed that they had become more educated than their parents and ancestors, so they are more likely to consider that allopathic medicines are more trusted and effective than root and folk medicines. Mr. Z stated,

We have been pretty much absorbed into the American dream and the American promise… . We needed those old practices and those old traditions to sustain us, and they come from our African heritage… . [Folk medicine] has been passed down to a number of people, and a lot of people heard about it and had an interest in it and practiced it themselves or made it up themselves or so forth and so on. But that is pretty much dying out now.

Mr. Z explained the reason that he did not use root doctors or other folk practitioners to treat his prostate cancer. He noted,

I think the reason why I probably haven’t delved in that order or developed an interest in [using root doctors to cure illness] is because it has probably been educated out of me. The more education we get, the further we get away from tradition, to the point we think we know it all. Oh, bad mistake.

Importance of trust in selected healthcare providers

All of the participants suggested that trusting in their healthcare providers was very important in their decisions for treatment. Everyone articulated the importance of healthcare providers’ recommendations and knowledge to help them manage and decide about their medical care.

Although the men in the sample believed and had faith in God, they conveyed that they would not forego medical treatment and trust God fully to treat their prostate cancer. Each participant acknowledged that he would get medical treatment during his illness. Many of the men stated that people have to help themselves to get well and not rely solely on God. They referred to the phrase “helping themselves” as God not doing everything. They hinted at the relationship between themselves and God as a partnership in which both parties must work to accomplish the goal of curing their prostate cancer. When asked about the relationship between God and prostate cancer, Mr. T stated, “[God is] the master. He’s the one that brought me through. Through the Holy Spirit and his grace, because like the doctor say, you got to help God, you just can’t depend on God to do everything.”

The men had strong beliefs in God, spirituality, and religion, but they did not refuse conventional allopathic treatments. They used God, spirituality, and religion to complement their allopathic medical treatment as opposed to using God as the sole intervention for their cancer.

How men decide on what to believe about complementary and alternative medicine modalities

All of the participants had opinions about CAM use and its effects on prostate cancer and general health. Five of the participants thought that some CAM modalities might help; eight individuals thought some CAM treatments (excluding prayer) were shams, whereas eight did not know whether some CAM treatments help. This theme was the most intriguing because researchers should examine how African American men decide what to believe in or trust to improve their health. The theme was supported by a level of skepticism about CAM modalities, other than prayer, held by the participants.

The men considered a spectrum of CAM modalities as therapy. Some men were willing to try selected CAM treatments, whereas others refused to consider their use. At one end of the spectrum was Mr. O, who, when asked about taking any products other than what the doctor prescribed for his prostate, stated, “No, I take only the medications that are prescribed. I don’t believe in voodoo medicine. I try to take as little medicine as possible. Unless it is prescribed, I don’t take any other medicine.”

In the middle of the spectrum is Mr. Z’s attitude toward root medicine. He was skeptical but respectful of those CAM modalities, saying,

I don’t know if it is coincidence or probability in numbers, but occasionally there will be an incidence of a situation existing, and a hex or a prayer or a root being applied to the situation, and the situation resolving itself. So that might have been coincidence, or might have been just the situation was going to resolve itself anyway, or the root. I don’t poke a stick at those roots. I don’t criticize it, and I don’t say it don’t exist, and I don’t talk ill of the practitioners.

On the other end of the spectrum is Mr. Z’s attitude toward herbal CAM. He was skeptical, unsure of its mechanism, but willing to try it, noting,

And also, not divulging what I was doing, but I talked to some other people about herbs and so forth and so on, and they either knew about it and wasn’t sure, nobody was sure how effective it was, or they didn’t know about it at all.

However, Mr. Z initially did not tell his physicians that he was using an herbal mixture; he said that he was embarrassed to tell them for fear of ridicule and how they might view him afterward.

The present sample of patients exhibited widespread skepticism and negative thoughts about the use of CAM modalities. Without exception, all 14 participants expressed skepticism of CAM use other than prayer because of their limited knowledge about how CAM therapies work and their efficacy. Their lack of knowledge about CAM and the efficacy of selected modalities may be the result of a limited amount of information and communication that healthcare providers relay to patients regarding CAM. However, some men still were willing to try CAM. The spectrum of skepticism and the role it plays in decision making is important to note in this group because it helps to identify factors that may influence African American men’s decisions that affect their health.

Discussion

The men in the current study were willing to share the experiences they had with prostate cancer, although other studies have found that cancer is not talked about openly among African Americans because of its associated stigma (Gray, Fitch, Phillips, Labrecque, & Fergus, 2000; Woods, Montgomery, Belliard, Ramirez-Johnson, & Wilson, 2004; Woods, Montgomery, & Herring, 2004). The lack of suspicion and distrust of physicians and other healthcare providers was the most important finding in the present investigation. Other studies have found that many African Americans distrust healthcare professionals (Agho & Lewis, 2001; Farkas et al., 2000; Kendall & Hatton, 2002; Marks, 2002; Wolff et al., 2003), which may contribute to documented health disparities. The current study suggests that a greater heterogeneity in the trust of caregivers exists than previously reported. The authors have documented a subgroup in the African American population that deeply trusts their healthcare providers and respects the treatment recommendations that providers offer. Thus, healthcare providers should recognize that many African Americans do not distrust them and are willing to work as a team to improve their health.

Another important finding in this research was how the men in the sample decided what to believe. By way of faith in God and previous experiences of family, friends, healthcare providers, and education, the men’s cultural beliefs and experiences have transformed their way of thinking about health and decision making through the years. Similar to what other studies (Jenkins & Pargament, 1995; Lannin et al., 1998; Mathews, Lannin, & Mitchell, 1994) have reported, the present study suggests that spirituality, religiosity, cultural beliefs, and experiences may influence what decisions people make after being diagnosed with cancer. Nurses have a vital role in addressing the positive, skeptical, and negative views about CAM. Nurses need knowledge about common CAM modalities that are used in the population. Because nurses are usually the healthcare providers who have the most contact with patients, they are in a position to explain the essential issues related to the use of CAM, including the importance of telling healthcare providers if CAM is being used to avoid any potential side effects. Nurses should explain to patients that just because a CAM (e.g., an herb) says that it is “natural” does not mean that it is always safe, and that patients must read labels on CAM products that are taken by mouth. Patients also should be instructed to stop taking the product and notify a healthcare provider if they experience noticeable side effects from CAM. African Americans may use CAM alone or in conjunction with conventional allopathic medicines, depending on their cultural beliefs and experiences. Such experiences shaped the way the men thought about and took action to treat their prostate cancer, which may offer some explanation about African American men’s decision-making process and decision choices.

Study Limitations

The present investigation about CAM modalities and beliefs of African American survivors of prostate cancer was designed as a pilot study. Although qualitative data may help clinicians appreciate how African American men understand their experiences with prostate cancer, the findings cannot be generalized to the greater population of African American survivors of prostate cancer because the sample consisted of only 14 participants. However, the findings are useful in generating hypotheses for future studies.

Conclusions

Several findings from the study offer new insights and additional information for the literature about prostate cancer and CAM modality use among African Americans that will make healthcare professionals and the public more aware of the beliefs and needs of African American men diagnosed with prostate cancer. In previous CAM literature (DeLisser, 2000; Galanter, 1997; McIntosh, Kojetin, & Spilka, 1985; Pargament & Park, 1995), cultural beliefs often are cited as barriers to obtaining adequate access and appropriate health care. Findings from the current study, however, suggest that CAM modalities, particularly prayer and spirituality, may be used as facilitators in health care. Acknowledging that spiritual and religious beliefs are prevalent among African American men may help healthcare professionals provide a more supportive environment that, in turn, may permit African American patients with prostate cancer to be more receptive of allopathic medical treatments and more willing to seek healthcare treatment. These prostate cancer survivors expressed a strong belief in God, prayer, and spirituality in relationship to health and their prostate cancer, although they held strong beliefs that allopathic treatment was needed to treat their cancer. More research is needed to determine whether participants in this study are representative of the larger population. Meanwhile, healthcare providers’ awareness of the use of CAM by this population may help to ensure safe patient care.

Key Points.

Cultural and complementary therapy beliefs are important in the way that African Americans think about their health.

Cultural and complementary therapy beliefs are important in the way that African Americans think about their health. African Americans may use complementary modalities to treat their prostate cancer or other health-related problems, which is important information for healthcare professionals.

African Americans may use complementary modalities to treat their prostate cancer or other health-related problems, which is important information for healthcare professionals. Spirituality and prayer play a vital role in many African Americans that can be advantageous and deleterious.

Spirituality and prayer play a vital role in many African Americans that can be advantageous and deleterious.

Contributor Information

Randy A. Jones, School of Nursing at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Ann Gill Taylor, School of Nursing at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Cheryl Bourguignon, School of Nursing at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Richard Steeves, School of Nursing at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Gertrude Fraser, Department of Anthropology at the University of Virginia.

Marguerite Lippert, Urology Department at the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville.

Dan Theodorescu, Urology Department at the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville.

Holly Mathews, Department of Anthropology at East Carolina University in Greenville, NC.

Kerry Laing Kilbridge, Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Virginia Medical Center..

References

- Agho AO, Lewis MA. Correlates of actual and perceived knowledge of prostate cancer among African Americans. Cancer Nursing. 2001;24:165–171. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200106000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society [Retrieved January 26, 2007];Cancer facts and figures 2007. 2007 from http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007PWSecured.pdf.

- Cohen M, Kahn D, Steeves R. Hermeneutic phenomenology: A practical guide for nurse researchers. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2nd ed Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- DeLisser H. [Retrieved April 16, 2005];Spiritual healing: Palliation and terminal care. 2000 from http://www.pennhealth.com/homecare/phys_update/2000_winter.html.

- Diefenbach MA, Hamrick N, Uzzo R, Pollack A, Horwitz E, Greenberg R, et al. Clinical, demographic, and psychosocial correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use by men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. Journal of Urology. 2003;170:166–169. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000070963.12496.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas A, Marcella S, Rhoads GG. Ethnic and racial differences in prostate cancer incidence and mortality. Ethnicity and Disease. 2000;10:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M. Spiritual recovery movements and contemporary medical care. Psychiatry. 1997;60:211–223. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1997.11024799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RE, Fitch M, Phillips C, Labrecque M, Fergus K. To tell or not to tell: Patterns of disclosure among men with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;9:273–282. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200007/08)9:4<273::aid-pon463>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JD, Bissonette EA, Boyd JC, Theodorescu D. Motivations and influences on the use of complementary medicine in patients with localized prostate cancer treated with curative intent: Results of a pilot study. BJU International. 2003;91:603–607. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins R, Pargament K. Religion and spirituality as resources for coping with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1995;13(1/2):51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, Wenzel J. Prostate cancer among African-American males: Understanding the current issues. Journal of National Black Nurses Association. 2005;16(1):55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall J, Hatton D. Racism as a source of health disparity in families with children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Advances in Nursing Science. 2002;25(2):22–39. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney AY, Emery G, Dudley WN, Croyle RT. Screening behaviors among African American women at high risk for breast cancer: Do beliefs about God matter? Oncology Nursing Forum. 2002;29:835–843. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.835-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannin DR, Mathews HF, Mitchell J, Swanson MS, Swanson FH, Edwards MS. Influence of socioeconomic and cultural factors on racial differences in late-stage presentation of breast cancer. JAMA. 1998;279:1801–1807. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.22.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Chang JS, Jacobs B, Wrensch MR. Complementary and alternative medicine use among men with prostate cancer in 4 ethnic populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1606–1609. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis ML, Christie JD, Silvestri GA, Kaiser L, Santiago S, Hansen-Flaschen J. Racial differences pertaining to a belief about lung cancer surgery: Results of a multicenter survey. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;139:558–563. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-7-200310070-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J. Identifying the causes of health disparities. Chronic Disease Notes and Reports. 2002;15(2):2. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews H, Lannin D, Mitchell J. Coming to terms with advanced breast cancer: Black women’s narratives from eastern North Carolina. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38:789–800. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh D, Kojetin B, Spilka B. Form of personal faith and general and specific locus of control. Presentation at the Convention of the Rocky Mountain Psychological Association; Tucson, AZ. Apr, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine [Retrieved February 16, 2007];CAM basics: What is CAM? 2007 from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam.

- Pargament K, Park C. Merely a defense? The variety of religious means and ends. Journal of Social Issues. 1995;51(2):13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ries L, Harkins D, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller B, Feuer E, et al. [Retrieved January 24, 2007];SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2003. 2006 from http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2003.

- Weinrich S, Royal C, Pettaway CA, Dunston G, Faison-Smith L, Priest JH, et al. Interest in genetic prostate cancer susceptibility testing among African American men. Cancer Nursing. 2002;25:28–34. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, Bates T, Beck B, Young S, Ahmed SM, Maurana C. Cancer prevention in underserved African American communities: Barriers and effective strategies—A review of the literature. WMJ. 2003;102(5):36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Belliard JC, Ramirez-Johnson J, Wilson CM. Culture, black men, and prostate cancer: What is reality? Cancer Control. 2004;11:388–396. doi: 10.1177/107327480401100606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Herring RP. Recruiting black/African American men for research on prostate cancer prevention. Cancer. 2004;100:1017–1025. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]