Abstract

Chronic treatment of mice with an enterically released formulation of rapamycin (eRapa) extends median and maximum life span, partly by attenuating cancer. The mechanistic basis of this response is not known. To gain a better understanding of these in vivo effects, we used a defined preclinical model of neuroendocrine cancer, Rb1+/− mice. Previous results showed that diet restriction (DR) had minimal or no effect on the lifespan of Rb1+/− mice, suggesting that the beneficial response to DR is dependent on pRb1. Since long-term eRapa treatment may at least partially mimic chronic DR in lifespan extension, we predicted that it would have a minimal effect in Rb1+/− mice. Beginning at 9 weeks of age until death, we fed Rb1+/− mice a diet without or with eRapa at 14 mg/kg food, which results in an approximate dose of 2.24 mg/kg body weight per day, and yielded rapamycin blood levels of about 4 ng/ml. Surprisingly, we found that eRapa dramatically extended life span of both female and male Rb1+/− mice, and slowed the appearance and growth of pituitary and decreased the incidence of thyroid tumors commonly observed in these mice. In this model, eRapa appears to act differently than DR, suggesting diverse mechanisms of action on survival and anti-tumor effects. In particular the beneficial effects of rapamycin did not depend on the dose of Rb1.

Keywords: mTOR, rapamycin, Rb1, neuroendocrine tumors

INTRODUCTION

Age is by far the biggest independent risk factor for a wide range of intrinsic diseases [1], including most types of cancer [2]. The age-adjusted cancer mortality rate for persons over 65 years of age is 15-times greater than for younger individuals [3]. Numerous studies demonstrate that age retarding interventions reduce cancer by decreasing incidence and/or severity (Reviewed in [4]). Diet restriction (DR) has a long history of retarding cancer [5] and most of the other age-associated diseases [6], consistent with life span extension in a wide range of organisms [7]. Genetic interventions resulting in pituitary dwarfism in mice, which causes growth factor reduction (GFR) and a reduction in associated signaling, also result in maximum lifespan extension [8], with a concomitant reduction in cancer severity [9, 10]. Thus, factors that inhibit growth appear to extend life span and reduce cancer.

mTORC1 (mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 1) is central to cell growth by integrating upstream signals that include nutrients, growth factors and energy levels with stress responses for regulated cell growth. Thus, chronic mTORC1 inhibition could act similarly to DR and GFR. Supporting this possibility, the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, increases life span in a variety of organisms including yeast [11], nematodes [12] and flies [13]. Using a chow containing a novel formulation of enterically delivered rapamycin (eRapa [14]), the NIA Intervention Testing Program [15] reported that long-term treatment extends both median and maximum lifespan of genetically heterogeneous mice (UM-HET3), even when started in late adulthood (20 months of age) [16], or at 9 months of age [17]. eRapa is the first drug reported to be capable of extending both median and maximum lifespan.

One explanation for the lifespan enhancement by eRapa is that chronic mTOR inhibition delays the onset and growth of neoplasms. Indeed, chronic eRapa (2.24 mg/kg/day diet) treatment reduced the incidence of lymphoma and hemangiosarcoma (two major cancers in the genetically heterogeneous mice studied by the ITP), and increased the mean age at death due to liver, lung and mammary tumors [16, 17]. Alternate possibilities are that the immune systems of treated mice better defend against their cancers or that the mice simply tolerate them longer. What is the basis of eRapa's ability to reduce cancer, and how does it compare to DR?

To gain an understanding of how chronic eRapa treatment compares with DR and affects cancer development, growth and progression, we used a mouse model deficient in the prototypical tumor suppressor, Rb1. Rb1 regulates cell cycle checkpoints for differentiation and in response to stress and is important for genome maintenance [18]. Rb1+/− mice are highly predisposed to cancers of neuroendocrine origin [19] including pituitary (intermediate and anterior lobe), thyroid C-cell (which can metastasize to lung), and adrenal. Tumorigenic cells form after losing the remaining functional copy of the Rb1 tumor suppressor gene. The complete penetrance of tumor formation, growth and progression results in a short lifespan for Rb1+/− mice, which, unlike wild type mice, is minimally affected by diet restriction [20]. If eRapa acts in a similar manner to DR [16], we predicted that chronic eRapa treatment of Rb1+/− mice would also have minimal effects on tumor development, growth, progression and life span. Surprisingly we find that eRapa treatment has a dramatic and positive effect on life span in both sexes of Rb1+/− mice, which is associated with slower tumor development and growth.

RESULTS

To address the question of whether eRapa mimics DR in mice deficient for a prototypical tumor suppressor gene function, we initiated chronic treatment by feeding randomly grouped males and females chow that included either eRapa at the concentration previously shown to extend life span (14 mg/kg food), [16, 17] or Eudragit (empty capsule control). Treatment was begun at approximately 9 weeks of age (>80% of animals started between 8-10 weeks (minimum at 7 weeks and maximum at 12 weeks, Table S1). Mice continued on these diets for the remainder of their lives. Based on the average amount of chow consumed per day, this delivers an approximate rapamycin dose of 2.24 mg/kg body weight/day [16]. Blood levels of rapamycin (determined by a mass spectrometry) averaged 3.9 ng/ml for males, 3.8 ng/ml for females for Rb1+/− mice and 3.4 for males and 4.6 ng/ml for females for Rb1+/+ mice (Figure S1). Hematocrits were performed on blood from Rb1+/+ mice between 18 and 24 months of age and readings indicated normal values for mice (between 40 and 49%), indicating that long-term eRapa treatment does not adversely effect red blood cell production (data not included).

eRapa extended life span of Rb1+/− mice

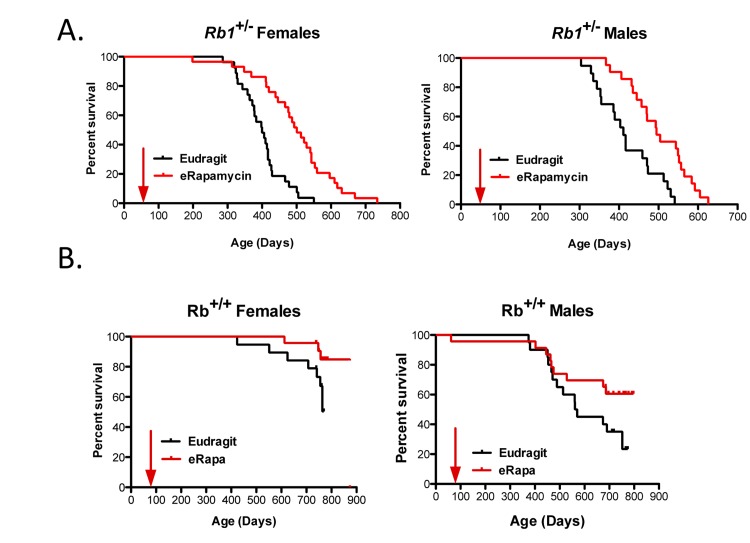

Unlike most mouse models of cancer [5], 50% DR had little (if any) effect on the development, growth and progression of neuroendocrine tumors or on life span ofRb1+/− mice [20]. Since rapamycin has been predicted to act in a similar way to DR [16], we investigated if eRapa would also have little effect in this model. In stark contrast to DR, Figure 1A shows that Rb1+/− males and females derive a significant longevity benefit from chronic treatment with eRapa. The Eudragit control-fed mice had a shorter mean life span than the eRapa-fed cohort for both females (377.5 versus 411 days) and males (mean age is 368.8 versus 419.8 days). Sex did not modulate the effect of eRapa on Rb1+/− animals (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Survival plots for male and female Rb1+/− (A) and Rb1+/+ (B) mice, comparing control-fed mice to those fed eRapa in the diet starting at approximately 9 weeks of age (indicated by arrow). Control (black line) and eRapa (red line) survival curves are shown. The horizontal axes represent life span in days and the vertical axes represent survivorship. Rb1+/− mice obtained from the NCI Mouse Repository were bred by the Nathan Shock animal core to obtain the cohorts of male and female mice used in this study. Genotype was confirmed as previously described [20]. eRapa mice were fed microencapsulated rapamycin-containing food (14mg/kg food designed to deliver approximately 2.24mg of rapamycin per kg body weight/day that achieved about 4 ng/ml blood [14]. Diets were prepared by TestDiet, Inc., Richmond, IN using Purina 5LG6 as the base [14]. Control diet was the same but with empty capsules. P values in (B) were calculated by the log-rank test.

Table 1. eRapa effects on survival of Rb1+/− mice.

| Coefficient | Hazard Ratio | SE | z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eRapa | −1.3177 | 0.2678 | 0.2400 | −5.4909 | 0.00000004 |

| Sex | 0.1693 | 1.1844 | 0.2144 | 0.8005 | 0.42344718 |

Male and female Rb1+/+ littermates of the Rb1+/− mice were also fed eRapa or control diets to ensure that this particular mutant strain (with a C57BL/6 background) is responsive to rapamycin. Once all Rb1+/− mice had died and the effects of eRapa were evident, the Rb1+/+ littermates were euthanized. At this time, as expected, eRapa improved survival for both male and female Rb1+/+ mice as well (Fig. 1B). Similar to the previous results from the Intervention Testing Program eRapa experiments [16, 17], lifespan was extended more in females than in males (Table 2) in wild type (WT) littermates.

Table 2. eRapa effects on survival of Rb1+/+ mice.

| Coefficient | Hazard Ratio | SE | z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eRapa | −0.9305 | 0.3943 | 0.3631 | −2.5625 | 0.01039082 |

| Sex | −1.2818 | 0.2775 | 0.3840 | −3.3382 | 0.00084312 |

eRapa effects on tumor incidence at the end of life

At necropsy, Rb1+/− mice were evaluated for the presence of neuroendocrine tumors and lung metastases. As shown in Table 3, there were no differences in the eRapa and Eudragit control groups in terms of presence of pituitary tumors (although we did observe a delay in their detection and reduction in size by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), discussed below). We did observe a decreased incidence of thyroid C-cell carcinomas in the eRapa treated group of Rb1+/− mice (p = 0.0112). Except for the modest decrease in thyroid tumors, this tumor spectrum is similar to Rb1 heterozygotes treated with DR compared to those fed ad libitum [20]. Along with the decrease in thyroid C-cell tumors, eRapa also tended to reduce the incidence and severity of C-cell lung metastases (Table 4). Thus mice have a decreased cancer burden and live with tumors longer.

Table 3. Pathology of Rb1+/− mice at necropsy.

| Eudragit | eRapa | |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Incidence | ||

| Pituitary | 97.5% (40) | 100%a (39) |

| Thyroid | 90.0% (40) | 66.7%b (39) |

| Thyroid with lung metastases | 37.5% (40) | 28.2%c (39) |

| Thyroid with adrenal metastases | 2.5% (40) | 7.7%d (39) |

| Adrenal | 30.0% (40) | 23.1%e (39) |

p = 0.9858,

p = 0.0112;

p = 0.3859;

p = 0.5472,

p = 0.4925

Two tailed, unpaired t test, GraphPad Prism.

Table 4. Incidence and pathology of Rb1+/− lung metastases.

| Eudragit | eRapa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Grade | ||||

| 0 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (Gr 1-4) | 5 | 10 | 4 | 7 |

eRapa delayed tumor development and slowed growth

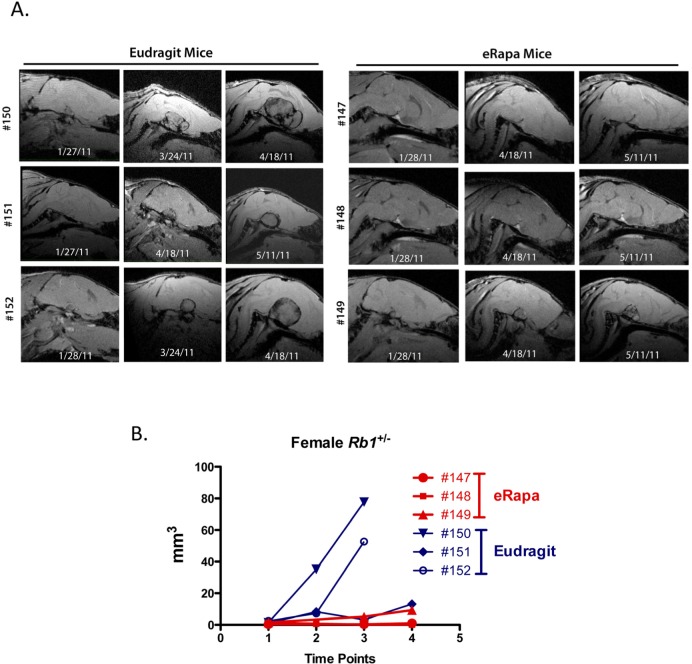

Is delayed and/or reduced tumor growth the basis of life span extension by eRapa in this model? To address this question, we took advantage of the synchronous (spatial and temporal) development of tumors in this model Nikitin et al. [19, 21]. Rb1-deficient cells are first identified as atypical proliferates in the intermediate and anterior lobes of the pituitary, thyroid and parathyroid glands and the adrenal medulla at about 12 weeks of postnatal development. Atypical proliferates eventually form gross tumors with varying degrees of malignancy by postnatal day 350. Since we started treatment at around 8 weeks of age, eRapa might have an effect on the initiating events leading to loss of heterozygosity and/or subsequent formation of atypically proliferating cells. Perhaps more likely, eRapa slows growth and development of proliferates to gross tumors, which had probably begun at or around the time treatment was started. To test this latter possibility, we used MRI to follow pituitary and thyroid tumor development and growth in a subset of eRapa-treatedRb1+/− mice (8 mice per treatment group were imaged between 1 and 4 times up to twice a month). MRI is well suited for following head and neck tumors that correspond to the primary tumor types Rb1+/− mice develop. An initial cohort was used to identify the best timeframe for MRI scans. For this, 6 female Rb1+/+ mice (3 per group) and 10 Rb1+/− mice (3 per group in males and 2 per group in females) were imaged in a single session or with 2 serial scans. This study indicated the ideal timeframe to image pituitary tumors was a window between 9 and 12 months of age, which covers the time from initial detection through monitoring tumor growth.

Age matched Rb1+/− females (3 per group) were scanned using MRI at 9, 11 and 12 months of age (Figure 2A shows sagittal plane sections of the serially acquired MRI images through the pituitary of eRapa and Eudragit treated mice). Calculated volumes based on the MRI image stacks (analyzed blind by a single radiologist, RLH) were plotted versus age at the date of imaging. In concert with extended longevity, the detection of pituitary tumors was delayed with a decrease in their growth in the eRapa-treated mice. Figure 2B shows that eRapa delayed development and/or reduced tumor growth at each time point when mice were imaged. More Rb1+/− mice had detectable tumors identified during two separate MRI imaging sessions from the Eudragit control cohort (4 pituitary and 2 thyroid tumors out of 8 mice in March 2011 scan and 7 pituitary and 4 thyroid tumors out of 8 mice in April 2011 scan) compared to the mice eRapa-fed cohort (1 pituitary and 0 thyroid tumors out of 8 mice in March 2011 scan and 2 pituitary and 3 thyroid tumors out of 8 mice in April 2011 scan). Longitudinal monitoring allowed us to conclude that chronic rapamycin delays both the development of visible tumors and inhibited the growth of tumors once they were present.

Figure 2.

Effects of eRapa on pituitary and thyroid tumor development and growth. To identify effects on tumors, we used MRI as a non-invasive method to longitudinally monitor individual Rb+/− mice. High-resolution images were obtained on a very high field strength Bruker Pharmascan 7.0T animal MRI scanner using a coil to focus on pituitary and thyroid tumors. Images were acquired using a spoiled gradient echo named Fast low angle shot MRI (FLASH) on the scanner. Images were acquired to yield predominantly T1 weighted contrast with TE (echo time) 4.5 msec, TR (repetition time) 450 msec, FA (Flip angle) 40 degrees, FOV (field of view) 20 x 20 mm, in plane spatial resolution 0.078 x 0.078 mm. Tumor volume was determined for each time point. (A) Serially acquired MRI images from eRapa and Eudragit-fed control mice at 9, 11 and 12 months of age. (B) Tumor volumes calculated from MRI image stacks at each time point comparing individual mice at multiple ages. Tumors in two of the Eudragit-fed (control) mice are detected earlier and grow faster than the 3 eRapa-fed mice.

DISCUSSION

In mice, pRb1 is critical for DR-mediated lifespan extension [20], but not rapamycin-mediated life span extension. It is unclear why this is the case, since both of these interventions chronically inhibit mTORC1 [22]. However, differences in the downstream in vivo effects of DR and rapamycin have been previously reported [22]. As previously described by Harrison et al. [16], a distinguishing feature of eRapa is its ability to extend median and maximum life when the intervention starts at a relatively old age (600 days) in mice. By comparison, DR in most [23] but not all [24] reports shows little if any longevity benefit when started after 550 days of age (equivalent to 60 human years). DR started at 6 weeks of age reduced body growth for Rb1+/− mice but did not affect growth of Rb1−/− tumors [20]. In contrast to DR, chronic eRapa treatment did not affect body weight of Rb1+/− mice (Livi et al., in preparation), but did reduce tumor growth. Previous studies in fruit flies show that rapamycin extends life span through a mechanism that is at least partly independent of TOR [13]. Consistent with those results, we find that eRapa, but not DR, extended life span and reduced the growth of neuroendocrine tumors in the Rb1+/− model. It will be interesting to determine if pRb1 might be at least partially involved in those settings where responses to chronic eRapa and DR diverge.

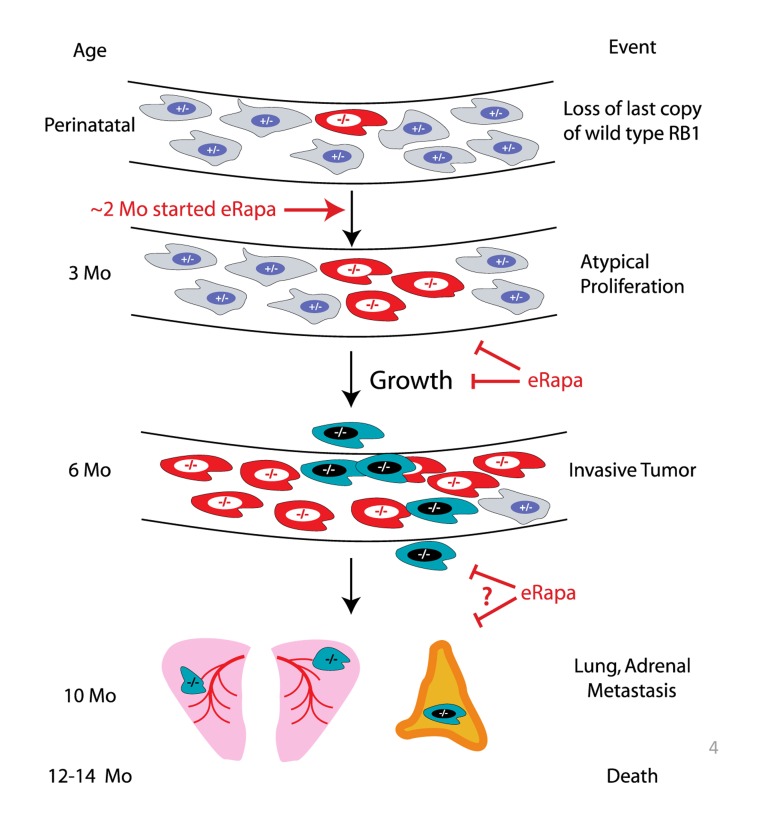

Based on the longitudinal imaging data acquired by MRI (Figure 2), eRapa appears to inhibit Rb1−/− pituitary tumor development and growth in Rb1+/− mice (summarized in Figure 3), which is likely a major factor in its ability to extend lifespan in this model. Since we started eRapa at between 2 and 3 months of age, it would be interesting to know if it affects loss of heterozygosity (LOH) (Figure 3) in neuroendocrine tissues. The significant reduction in the incidence of thyroid C-cell carcinoma at necropsy in eRapa treated Rb1+/− mice (Table 3) also likely contributes to extended longevity. We also observed an apparent lessening of severity in lung metastases (Table 4), but this may be due to overall reduction of C-cell carcinomas. Metastasis of these to tumors to the adrenal (Table 3) has, to our knowledge, not been previously reported. A recent report linked an increase in metastasis with RAD001 treatment in a rat model of transplanted neuroendocrine tumors, which the authors attributed to alternations in tissue immune microenvironment [25]. Since RAD001 treatment was started subsequent to tumor implantation, it might be interesting to test this model in a prevention rather than treatment setting.

Figure 3.

Summary of eRapa effects in the Rb1+/− model of neuroendocrine tumorigenesis. Our MRI data are consistent with a delay of tumor development perhaps by inhibition of atypical proliferates and reduction in tumor growth. eRapa may inhibit lung metastasis and slow their growth.

Two reports have linked pRb1 and mTOR. A genetic study in D. melanogaster established synergy between deletion of mTOR and pRb1 using an in vivo synthetic lethality screen of Rb-negative cells [26]. These authors found that inactivation of gig (fly TSC2) and rbf (fly Rb) is synergistically responsible for oxidative stress leading to lethality. In a separate study, El-Naggar et al., [27] found that loss of the Rb1 family (Rb1, Rbl1 and Rbl2) in primary cells derived from triple-knockout mice led to overexpression of mTOR and constitutive phosphorylation of Ser473 on Akt , which is oncogenic. The inhibition of tumor development and growth in Rb1+/− mice by eRapa is also consistent with a recent report showing that mTOR inhibition partially alleviated tumor development in an RbF/F;K14creER™; p107−/− model of squamous cell carcinoma [28], and with several reports demonstrating the effectiveness of rapamycin in mouse cancer models for tumor reduction and life span extension [29-31]. Potential mechanism may be by way of indirect effects or rapamycin on the tumor microenvironment [32] and/or senescent cells [33].

The reduction in lung metastases is consistent with ribosome profiling that revealed transcript-specific translational control mediated by oncogenic mTOR signaling, including a distinct set of pro-invasion and metastasis genes [34]. It will be interesting to determine whether chronic eRapa treatment affects these genes in thyroid C-cell neoplasms. We also observed metastasis of thyroid tumors to adrenal glands, albeit at a low frequency but eRapa treatment did not effect.

Neuroendocrine tumors are unique in their ability to secrete hormones or deleterious bioactive products [35]. It was previously reported that the rapalog Everolimus (RAD-001) in combination with ocreotide lanreotide (compared to placebo) improved the clinical picture of carcinoid patients by reducing circulating chromogranin A and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, two tumor-secreted bioactive products responsible for some of the symptoms [36]. Thus, another potential mechanism for life span extension in Rb1+/− mice by eRapa could be due the prevention of the production and/or secretion of hormones or deleterious bioactive factors.

Rb1 is known to have an important role in somatic growth regulation, since increased RB1 dose reduced animal size [37]. Determining if there is a link between Rb1 (a negative regulator of growth) and mTORC1 (a positive regulator of growth) in growth of tumors could suggest new therapeutic and prevention targets for drug development. One prediction is that mice over expressing pRb1 will have decreased mTOR activity and be long lived through prevention, delay or a reduction in severity of age-related diseases.

Here we show that eRapa extends the life span for Rb1+/− mice. We find eRapa-fed mice exhibit a delay in the onset and/or progression of neuroendocrine tumors. These results are in direct contrast with DR. Thus, mTORC1 inhibition and DR likely use different modes for life span extension.

METHODS

Mice and life span

Mice (strain B6.129S2(Cg)-Rb1tm1Tyj) for breeding were obtained from the NCI MMHCC Repository. Although they have similar phenotypes, the strain used in the diet restriction study by Sharp et al., [20] was different having been generated by Lee et al [38]. The procedures and experiments involving use of mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are consistent with the NIH Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research and Education, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Welfare Act (National Academy Press, Washington, DC). Genotyping was done as described previously [20]. Cohorts of mice were fed microencapsulated rapamycin-containing food (14 mg/kg food designed to deliver ~2.24 mg of rapamycin per kg body weight/day to achieve about 4 ng/ml of rapamycin per kg body weight/day) prepared by TestDiet, Inc., Richmond, IN using Purina 5LG6 as the base [14]. Control diet was the same but with empty capsules.

Rapamycin food concentration

Rapamycin was quantified in food using HPLC with tandem mass spectrometry detection. Briefly, 100 mg of food for spiked calibrators and unknown samples were crushed with a mortar and pestle, then vortexed vigorously with 10 μL of 250 μg/mL ASCO (internal standard) and 4.0 ml of mobile phase A. The samples were then mechanically shaken for 10 min, centrifuged for 10 min, and then centrifuged in microfilterfuge tubes for 1 minute. Ten μL of the final extracts was injected into the LC/MS/MS. The ratio of the peak area of rapamycin to that of the internal standard (response ratio) was compared against a linear regression of calibrator response ratios at rapamycin concentrations of 0, 2, 5, 10, 30, and 60 ng/mg of food to quantify rapamycin. The concentration of rapamycin in food was expressed as ng/mg food (parts per million).

Rapamycin blood measurements

Measurement of rapamycin used HPLC-tandem MS. RAPA and Ascomycin (ASCO) were obtained from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). HPLC grade methanol and acetonitrile were purchased from Fisher (Fair Lawn, NJ). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Milli-Q water was used for preparation of all solutions. RAPA and ASCO super stock solutions were prepared in methanol at a concentration of 1 mg/ml and stored in aliquots at −80°C. A working stock solution prepared each day from the super stock solutions at a concentration of 10 μg/ml was used to spike the calibrators.

Calibrator and unknown whole blood samples (100 μL) were mixed with 10 μL of 0.5 μg/mL ASCO (internal standard), and 300 μL of a solution containing 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate dissolved in 95% HPLC grade methanol. The samples were vortexed vigorously for 2 min, and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 5 min at 23°C (subsequent centrifugations were performed under the same conditions). Supernatants were transferred to 1.5 ml microfilterfuge tubes and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 1 min and then 40 μL of the final extracts were injected into the LC/MS/MS. The ratio of the peak area of rapamycin to that of the internal standard ASCO (response ratio) for each unknown sample was compared against a linear regression of calibrator response ratios at 0, 1.25, 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 50, and 100 ng/ml to quantify rapamycin.

The HPLC system consisted of a Shimadzu SCL-10A Controller, LC-10AD pump with a FCV-10AL mixing chamber (quarternary gradient), SIL-10AD autosampler, and an AB Sciex API 3200 tandem mass spectrometer with turbo ion spray. The analytical column was a Grace Alltima C18 (4.6 x 150 mm, 5 μ) purchased from Alltech (Deerfield, IL) and was maintained at 60°C during the chromatographic runs using a Shimadzu CTO-10A column oven. Mobile phase A contained 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid dissolved in HPLC grade methanol. Mobil phase B contained 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid dissolved in 90% HPLC grade methanol. The flow rate of the mobile phase was 0.5 ml/min. Rapamycin was eluted with a step gradient. The column was equilibrated with 100% mobile phase B. At 6.10 minutes after injection, the system was switched to 100% mobile phase A. Finally, at 15.1 min, the system was switched back to 100% mobile phase B in preparation for the next injection. The rapamycin transition was detected at 931.6 Da (precursor ion) and the daughter ion was detected at 864.5 Da. ASCO was detected at 809.574 Da and the daughter ion was 756.34 Da.

Survival Analysis Methods

An entry for each mouse in the study was created in a database used by the Nathan Shock Animal core. The age at which each animal died was recorded. Survival durations for animals that either lived past the end-date of the study, were terminated, or died accidentally were treated as right-censored events. Cox proportional hazard models [39] were fitted to the wild type and Rb1+/− subsets of the data, with eRapa and gender as additive predictor variables. Some animals were transferred to a different facility part-way through their life spans so the final facility at which they were housed was also added to the Cox models, as a stratifying variable. The R statistical language was used for the analysis [40, 41]. The mice in the life span studies were allowed to live out their life span, i.e., there was no censoring due to morbidity in the groups of mice used to measure lifespan of Rb1+/− mice. Mice were euthanized only if they were either [1] unable to eat or drink, [2] bleeding from a tumor or other condition, or [3] when they were laterally recumbent, i.e., they fail to move when prodded or are unable to right themselves.

MRI Methods

Images were acquired on a Bruker Pharmascan 7.0T MRI scanner. Images were obtained in the sagittal plane through the brain and coronal plain through the neck (focused on the thyroid gland) using 2D spoiled gradient echo technique to quickly obtain high-resolution images (fast low angle shot magnetic resonance imaging - FLASH on our scanner). FLASH protocol was TE/TR 5 msec/450msec, Averages 1, Flip angle 40 deg, Field of view 20 mm x 20 mm, matrix size 256x256, In plane resolution was 0.078 x 0.078 mm, slice thickness 0.5 mm. The FLASH sequence shows predominantly T1 weighted image contrast. A single blinded radiologist (RLH) evaluated images for the presence and tumor volume used to plot detection and growth data. Images were analyzed using an open source image processing software, OsiriX, version 2.7.5. The pituitary gland was identified on all images and volume was calculated by measuring the greatest anterior-posterior, cranial-caudal, and right-left length. Volumes were then determined using prolate ellipse formula. Data were then parsed by treatment group and plotted in Prism (GraphPad).

Procedures for examination of pathology in mice

Fixed tissues (in 10% neutralized formalin) were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Diagnosis of each histopathological change was made using histological classifications for aging mice as previously described [9, 20, 42, 43].

Pathology assessments

A list of lesions was compiled for each mouse. The severity of neoplastic lesions was assessed using the grading system previously described [9, 9, 20, 42, 43, 42, 43]. Two pathologists separately examined all of the samples without knowledge of their genotype or age. Briefly, lung pathology grade is based on the area of the lung section infiltrated by metastatic tumor tissue with 0 being no tumor cells observed and 4 being the largest area taken by tumor.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Gregory Friesenhahn for rapamycin blood level measurements, Jesse Usrey and Dr. Michael Duff Davis for technical assistance with MRI imaging. Viviane Diaz and the Nathan Shock Animal Core staff provided expert care for our mice. This work was supported by the following funding agencies: NIH (ISG 1RC2AG036613-01, Project 1, ZDS and PH; 2P01AG017242-12, PH; AG13319, YI; UL1RR025767, CTSA, Technology Transfer Resource to ZDS and CBL supported MRI imaging costs associated with this study), The Glenn Foundation for Medical Research (ZDS and YI), Department of Veteran Affairs (VA Merit Review Grant, YI). We would also like to thank the Cancer Therapy Research Center (CA054174), the NCRR (UL 1RR025767) and the RCMI (G12MD007591) for additional support.

Footnotes

ZDS and RS were unpaid consultants to Rapamycin Holdings, Inc. Other authors declare no conflicts.

REFERENCES

- Kirkwood TB. Gerontology: Healthy old age. Nature. 2008;455:739–740. doi: 10.1038/455739a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2007 Bethesday, MD: National Cance Institute. 2010 Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007//, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny MV, Campisi J. Cancer and aging: more puzzles, more promises? Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2615–2618. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.17.6626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp Z, Richardson A. Aging and cancer: can mTOR inhibitors kill two birds with one drug? Targeted Oncology. 2011;6:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s11523-011-0168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursting SD, Smith SM, Lashinger LM, Harvey AE, Perkins SN. Calories and carcinogenesis: lessons learned from 30 years of calorie restriction research. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:83–89. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending Healthy Life Span--From Yeast to Humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R, Colman RJ, Pérez V, Richardson AG. How Does Calorie Restriction Increase the Longevity of Mammals? Molecular Biology of Aging. In: Guarente LP, Partridge L, Wallace DC, editors. Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2008. pp. 409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Bartke A. Growth hormone, insulin and aging: The benefits of endocrine defects. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:108–111. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeno Y, Bronson RT, Hubbard GB, Lee S, Bartke A. Delayed Occurrence of Fatal Neoplastic Diseases in Ames Dwarf Mice: Correlation to Extended Longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:B291–B296. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.4.b291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Lee S, Cortez LA, Lew CM, Webb CR, et al. Reduced Incidence and Delayed Occurrence of Fatal Neoplastic Diseases in Growth Hormone Receptor/Binding Protein Knockout Mice. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2009;64A:522–529. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RW, 3rd, Kaeberlein M, Caldwell SD, Kennedy BK, Fields S. Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling. Genes Dev. 2006;20:174–184. doi: 10.1101/gad.1381406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robida-Stubbs S, Glover-Cutter K, Lamming DW, Mizunuma M, Narasimhan SD, Neumann-Haefelin E, et al. TOR Signaling and Rapamycin Influence Longevity by Regulating SKN-1/Nrf and DAF-16/FoxO. Cell Metabolism. 2012;15:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov I, Toivonen JM, Kerr F, Slack C, Jacobson J, Foley A, et al. Mechanisms of Life Span Extension by Rapamycin in the Fruit Fly Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metabolism. 2010;11:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadon NL, Strong R, Miller RA, Nelson J, Javors M, Sharp ZD, et al. Design of aging intervention studies: the NIA interventions testing program. AGE. 2008;30:187–199. doi: 10.1007/s11357-008-9048-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadon NL, Strong R, Miller RA, Nelson J, Javors M, Sharp ZD, et al. Design of aging intervention studies: the NIA interventions testing program. Age (Dordr) 2008;30:187–199. doi: 10.1007/s11357-008-9048-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA, Harrison DE, Astle CM, Baur JA, Boyd AR, de Cabo R, et al. Rapamycin, But Not Resveratrol or Simvastatin, Extends Life Span of Genetically Heterogeneous Mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:191–201. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Lee WH. The retinoblastoma gene: a prototypic and multifunctional tumor suppressor. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:2–18. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin AY, Juarez-Perez MI, Li S, Huang L, Lee WH. RB-mediated suppression of spontaneous multiple neuroendocrine neoplasia and lung metastases in Rb+/− mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Mar 30;96:3916–3921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp ZD, Lee WH, Nikitin AY, Flesken-Nikitin A, Ikeno Y, Reddick R, et al. Minimal effects of dietary restriction on neuroendocrine carcinogenesis in Rb+/− mice. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:179–183. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin A, Lee WH. Early loss of the retinoblastoma gene is associated with impaired growth inhibitory innervation during melanotroph carcinogenesis in Rb+/− mice. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1870–1879. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.15.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth Control and Disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoro EJ. Overview of caloric restriction and ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhahbi JM, Kim HJ, Mote PL, Beaver RJ, Spindler SR. Temporal linkage between the phenotypic and genomic responses to caloric restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5524–5529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305300101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pool SE, Bison S, Koelewijn SJ, van der Graaf LM, Melis M, Krenning EP, et al. mTOR inhibitor RAD001 promotes metastasis in a rat model of pancreaticneuroendocrine cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:12–18. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Gordon GM, Du CH, Xu J, Du W. Specific killing of Rb mutant cancer cells by inactivating TSC2. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Naggar S, Liu Y, Dean DC. Mutation of the Rb1 Pathway Leads to Overexpression of mTor, Constitutive Phosphorylation of Akt on Serine 473, Resistance to Anoikis and a Block in c-Raf Activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5710–5717. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00197-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa C, Santos M, Segrelles C, Duenas M, Lara MF, Agirre X, et al. A Novel Tumor suppressor network in squamous malignancies. Sci Rep. 2012;2:828. doi: 10.1038/srep00828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisimov VN, Zabezhinski MA, Popovich IG, Piskunova TS, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML, et al. Rapamycin Extends Maximal Lifespan in Cancer-Prone Mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2092–2097. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas M, Toshkov I, Kuropatwinski KK, Chernova OB, Polinsky A, Blagosklonny MV, et al. New nanoformulation of rapamycin Rapatar extends lifespan in homozygous p53−/− mice by delaying carcinogenesis. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:715–722. doi: 10.18632/aging.100496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova EA, Antoch MP, Novototskaya LR, Chernova OB, Paszkiewicz G, Leontieva OV, et al. Rapamycin extends lifespan and delays tumorigenesis in heterozygous p53+/− mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:709–714. doi: 10.18632/aging.100498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier I, Camacho J, Titchen K, Gonzales DM, Quann K, Bryant KG, et al. Caveolin-1 and accelerated host aging in the breast tumor microenvironment: chemoprevention with rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor and anti-aging drug. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:278–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny MV. Prevention of cancer by inhibiting aging. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1520–1524. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.10.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh AC, Liu Y, Edlind MP, Ingolia NT, Janes MR, Sher A, et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature. 2012;485:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogliotti L, Tampellini M, Stivanello M, Gorzegno G, Fabiani L. The clinical management of neuroendocrine tumors with long-acting repeatable (LAR) octreotide: comparison with standard subcutaneous octreotide therapy. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S105–109. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_2.s105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel ME, Hainsworth JD, Baudin E, Peeters M, Horsch D, Winkler RE, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable for the treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours associated with carcinoid syndrome (RADIANT-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2011;378:2005–2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin A, Shan B, Flesken-Nikitin A, Chang KH, Lee WH. The retinoblastoma gene regulates somatic growth during mouse development. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3110–3118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EY, Chang CY, Hu N, Wang YC, Lai CC, Herrup K, et al. Mice deficient for Rb are nonviable and show defects in neurogenesis and haematopoiesis. Nature. 1992;359:288–294. doi: 10.1038/359288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM. New York: Springer; 2000. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM. A package for Survival in S. Rochester, MN: Mayo Foundation; 2012.

- Team RDC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2012. Available from: http://www.R-project.org.

- Bronson RT, Lipman RD. Reduction in rate of occurrence of age related lesions in dietary restricted laboratory mice. Growth Dev Aging. 1991;55:169–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Lee S, Richardson A, Strong R, Diaz V, et al. Housing Density Does Not Influence the Longevity Effect of Calorie Restriction. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2005;60:1510–1517. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.12.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.