With increasing antibiotic resistance, oral chloramphenicol may be utilized more frequently; below we highlight the risk of toxic optic neuropathy.

Case report

A 66-year-old woman presented on October 2011 with a 10-day history of painless bilateral visual loss of subacute onset (over 48 h). She also described paraesthesiae of the limbs for a similar duration.

She has rheumatoid arthritis, treated with methotrexate (since 2002) and etanercept (2003–2009), and she required bilateral knee replacements in 2009. Her right knee replacement was revised and underwent six washouts for persistent infection. Previous antibiotics used for her knee infection included ceftriaxone, fusidic acid, amoxicillin, vancomycin and daptomycin. Chloramphenicol 4 g daily was started 14 weeks before the occurrence of visual loss.

Chloramphenicol had been discontinued five days before presentation. Her other medications included methotrexate, folic acid, tramadol, paracetamol, aspirin and omeprazole. She smokes 10 cigarettes daily and does not drink alcohol. She has a varied balanced diet. There is no relevant family history.

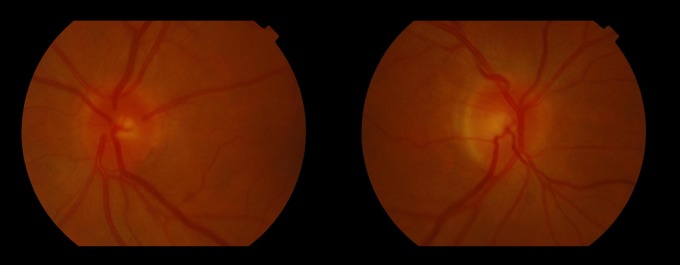

On examination at 10 days after onset of visual loss, she had a best corrected visual acuity of 3/24 (Snellen) bilaterally and centrocaecal scotomas on examination by confrontation with a red hat pin. None of the Ishihara colour plates could be read, not even the control plate. Both her optic discs were hyperaemic (see Figure 1). The rest of her cranial nerves and neurological examination of limbs were normal, except for bilateral L5 dermatomal loss to pinprick and abnormal proprioception at the great toe. Both temporal arteries were normal to palpation.

Figure 1.

Bilateral hyperaemic optic discs seen in our patient with chloramphenicol-associated toxic optic neuropathy

Investigations showed normochromic normocytic anaemia (haemoglobin 10.9 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 94 fL). C-reactive protein was elevated at 54.7 mg/L (normal <5). The rest of blood tests were unremarkable including vitamin B12, folate, methylmalonic acid, homocysteine, autoantibodies (antinuclear antibody, extractable nuclear antigen and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) and a genetic screen for Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy mutations.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain and orbits was normal and MRI spine showed mild degenerative changes at cervical spine only. Cerebrospinal fluid examination was normal. A visual evoked potential was performed after recovery and this was normal, as were nerve conduction studies.

A diagnosis of toxic optic neuropathy secondary to chloramphenicol was suspected. As stated above, the chloramphenicol had been stopped five days before presentation to us, i.e. on day 6 of visual symptoms. Four weeks after stopping chloramphenicol, vision improved to acuities of 6/5 (right), 6/6 (left) and normal visual fields, but reading of the Ishihara colour plates remained impaired at 8/13 bilaterally.

The patient elected to have an above knee amputation of her right leg, and is now mobilizing with a prosthetic limb and rehabilitation. At the onset of visual symptoms she developed paraesthesiae of limbs. Although the paraesthesiae improved, she is still symptomatic with this and the sensory loss in the left foot is impairing her prosthesis use.

Discussion

Chloramphenicol oral therapy was commonly used until the late 1980s, but with the publicized idiosyncratic reaction of bone marrow suppression1 and the availability of newer antibiotics, its use was slowly phased out, at least in the ‘developed’ world.2 However, with the increasing emergence of antibiotic resistance, older generations of antibiotics may potentially be used more frequently, as was the case in our patient. The previously reported adverse reactions to these older generation antibiotics may therefore be less familiar to the current generation of physicians.

Toxic optic neuropathy secondary to chloramphenicol was first described in 1950. Approximately 40 cases of chloramphenicol optic neuropathy were reported from 1950 to 1988, but for 23 years since then only two cases were reported,3–7 a trend that may reflect the reduction in chloramphenicol use.

The bone marrow suppression caused by chloramphenicol has long been recognized by physicians,1 leading to a severe idiosyncratic adverse reaction even with brief courses of treatment. By contrast, chloramphenicol toxic optic neuropathy is associated with prolonged use (more than 6 weeks) and high cumulative dose (>100 g).8 Knowledge of these risk factors, by avoiding prolonged courses or high doses, can potentially avoid this adverse reaction.

The visual loss in chloramphenicol toxic optic neuropathy may be sudden or subacute, and painful or painless. There may often be limb paraesthesiae preceding the visual symptoms.4 The typical ocular signs are bilateral optic disc swelling, retinal vessel tortuosity and retinal haemorrhages; our patient's optic discs were certainly hyperaemic, and possibly slightly swollen (see Figure 1). However, the fundi may also be normal. A centrocaecal scotoma is typically seen, and is pathognomonic for toxic/nutritional optic neuropathies. The differential diagnoses to be considered were nutritional optic neuropathy and Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy, both of which were excluded in our patient. Hypotheses suggested include mitochondrial inhibition and vitamin B metabolism inhibition by chloramphenicol.4,9

The treatment is to stop chloramphenicol, which often leads to good, or even full, recovery of vision.3,4,6 There is anecdotally reported use of high-dose vitamin B (pyridoxine and cyanocobalamin) but the evidence for this is not robust.8,10 Our patient recovered simply with stopping the offending drug.

Conclusion

We describe a case of toxic optic neuropathy secondary to chloramphenicol. Chloramphenicol optic neuropathy causes subacute visual loss with centrocaecal scotoma. The risk factors are prolonged treatment (>6 weeks) and a cumulative dose of >100 g. The management is to stop the drug. This case highlights the potential pitfalls resulting from the use of older generation antibiotics and lack of familiarity with their adverse effects. The problem is likely to become increasingly pertinent as antibiotic resistance increases.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethical approval

Written consent was received from the patient

Guarantor

SHW

Contributorship

All authors were involved in the conception of the case report and in its editing

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient for consent to present her case. This case was presented at the Association of British Neurologists annual meeting, June 2012

Reviewer

Ali Yagan

References

- 1.Best WR Chloramphenicol-associated blood dyscrasias. JAMA 1967;201:181–8 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gump DW Chloramphenicol: a 1981 view. Arch Intern Med Am Med Assoc 1981;141:573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godel V, Nemet P, Lazar M Chloramphenicol optic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:1417–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harley RD, Huang NN, Macri CH, Green WR Optic neuritis and optic atrophy following chloramphenicol in cystic fibrosis patients. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1970;74:1011–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joy R, Scalettar R, Sodee D Optic and peripheral neuritis. Probable effect of prolonged chloramphenicol therapy. JAMA 1960;173:1731–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang N, Giles C, Gregg R Optic neuritis and chloramphenicol. Archives of pediatrics and adolescent medicine. Am Med Assoc 1966;112:46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fung AT, Hudson B, Billson FA Chloramphenicol – not so innocuous: a case of optic neuritis. BMJ Case Rep 2011. Mar 3; pii: bcr1020103434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Huang NN, Harley RD, Promadhattavedi V, Sproul A Visual disturbances in cystic fibrosis following chloramphenicol administration. J Pediatrics 1966;68:32–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carelli V, Ross-Cisneros FN, Sadun AA Optic nerve degeneration and mitochondrial dysfunction: genetic and acquired optic neuropathies. Neurochem Int 2002;40:573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocke JG Chloramphenicol optic neuritis. Apparent protective effects of very high daily doses of pyridoxine and cyanocobalamin. Am J Dis Child 1967;114:424–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]