SUMMARY

As NAD+ is a rate-limiting co-substrate for the sirtuin enzymes, its modulation is emerging as a valuable tool to regulate sirtuin function and, consequently, oxidative metabolism. In line with this premise, decreased activity of PARP-1 or CD38 —both NAD+ consumers— increases NAD+ bioavailability, resulting in SIRT1 activation and protection against metabolic disease. Here we evaluated whether similar effects could be achieved by increasing the supply of nicotinamide riboside (NR), a recently described natural NAD+ precursor with the ability to increase NAD+ levels, Sir2-dependent gene silencing and replicative lifespan in yeast. We show that NR supplementation in mammalian cells and mouse tissues increases NAD+ levels and activates SIRT1 and SIRT3, culminating in enhanced oxidative metabolism and protection against high fat diet-induced metabolic abnormalities. Consequently, our results indicate that the natural vitamin, NR, could be used as a nutritional supplement to ameliorate metabolic and age-related disorders characterized by defective mitochondrial function.

INTRODUCTION

The administration of NAD+ precursors, mostly in the form of nicotinic acid (NA), has long been known to promote beneficial effects on blood lipid and cholesterol profiles and even to induce short-term improvement of type 2 diabetes (Karpe and Frayn, 2004). Unfortunately, NA treatment often leads to severe flushing, resulting in poor patient compliance (Bogan and Brenner, 2008). These side effects are mediated by the binding of NA to the GPR109A receptor (Benyo et al., 2005). We hence became interested in the possible therapeutic use of alternative NAD+ precursors that do not activate GPR109A.

NR was recently identified as a NAD+ precursor, with conserved metabolism from yeast to mammals (Bieganowski and Brenner, 2004). Importantly, NR is found in milk (Bieganowski and Brenner, 2004) constituting a dietary source for NAD+ production. Once it enters the cell, NR is metabolized into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) by a phosphorylation step catalyzed by the nicotinamide riboside kinases (NRKs) (Bieganowski and Brenner, 2004). In contrast to NR, NMN has not yet been found in dietary constituents and its presence in serum is a matter of debate (Hara et al., 2011; Revollo et al., 2007). This highlights how NR might be an important vehicular form of an NAD+ precursor, whose levels could be modulated through nutrition.

The sirtuins are a family of enzymes that use NAD+ as a cosubstrate to catalyze the deacetylation and/or mono-ADP-ribosylation of target proteins. One of their major particularities is that their Km for NAD+ is relatively high, making NAD+ a rate-limiting substrate for their reaction (Canto and Auwerx, 2012). Initial work by yeast biologists indicated that the activity of Sir2 (the yeast SIRT1 homolog) as an NAD+-coupled enzyme could provide a link between metabolism and gene silencing (Imai et al., 2000a; Imai et al., 2000b). In this way, Sir2 was proposed to mediate metabolic transcriptional adaptations linked to situations of nutrient scarcity, which are generally coupled to increased NAD+ levels (for review, see Houtkooper et al., 2010). During the last decade, an overwhelming body of evidence indicates that the activity of mammalian sirtuins, most notably SIRT1 and SIRT3, have the ability to enhance fat oxidation and prevent against metabolic disease (Hirschey et al., 2011; Lagouge et al., 2006; Pfluger et al., 2008). Therefore, strategies aimed to increase intracellular NAD+ levels have gained interest in order to activate sirtuins and battle metabolic damage. Validation of this concept was achieved recently, by demonstrating that pharmacological and genetic approaches aimed to reduce the activity of major NAD+ consuming activities in the cell, such as PARP-1 (Bai et al., 2011b) and CD38 (Barbosa et al., 2007), prompted an increase in NAD+ bioavailability and enhanced SIRT1 activity, ultimately leading to effective protection against metabolic disease. In this work we aimed to test whether similar effects could be achieved through dietary supplementation with a natural NAD+ precursor, such as NR.

RESULTS

NR increases intracellular and mitochondrial NAD+ content in mammalian cells and tissues

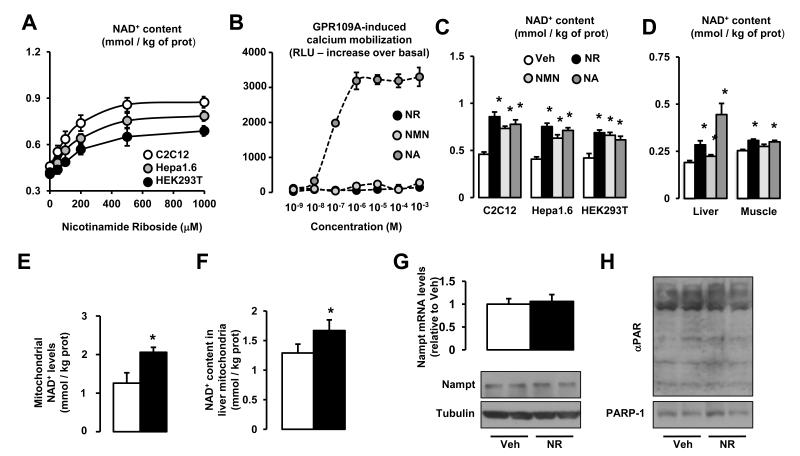

NR treatment dose-dependently increased intracellular NAD+ levels in murine and human cell lines (Fig.1A), with maximal effects at concentrations between 0.5 and 1 mM. In C2C12 myotubes, the Km for NR uptake was 172.3±17.6 μM, with a Vmax of 204.2±20.5 pmol/mg of protein/min. Unlike NA, both NR and another well-described NAD+ precursor, NMN (Revollo et al., 2007), did not activate GPR109A (Fig.1B), hence constituting valuable candidates to increase NAD+ levels without activating GPR109A. Strikingly, the ability of NR to increase intracellular NAD+ in mammalian cells was, at least, similar to that of these other precursors (Fig.1C). We next evaluated the efficacy of NR, NMN and NA to increase NAD+ in vivo by supplementing mouse chow with NR, NMN or NA at 400 mg/kg/day for one week. All compounds increased NAD+ levels in liver, but only NR and NA significantly enhanced muscle NAD+ content. (Fig.1D). These results illustrate how NR administration is a valid tool to boost NAD+ levels in mammalian cells and tissues without activating GPR109A.

Figure 1. Nicotinamide Riboside supplementation increases NAD+ content and sirtuin activity in cultured mammalian cells.

(A) C2C12 myotubes, Hepa1.6 and HEK293T cells were treated with nicotinamide riboside (NR) for 24 hrs and acidic extracts were obtained to measure total NAD+ intracellular content. (B) GPR109A-expressing Chem-4 cells were loaded with 3 μM Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester derivative (Fura-2/AM) for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, cells were washed with Hank’s balanced salt solution and calcium flux in response to nicotinic acid (NA; as positive control), NR and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) at the concentrations indicated was determined as indicated in methods. (C) C2C12 myotubes, Hepa1.6 and HEK293T cells were treated with either PBS (as Vehicle) or 0.5 mM of NR, NMN or NA for 24 hrs. Then total NAD+ intracellular content was determined as in (A). (D) C57Bl/6J mice were fed with chow containing vehicle (water) or either NR, NMN or NA at 400 mg/kg/day (n=8 mice per group). After one week, NAD+ content was determined in liver and quadriceps muscle. (E) HEK293T cells were treated with NR (0.5 mM, black bars) or vehicle (white bars) for 4 hrs. Then, cells were harvested and mitochondria were isolated for NAD+ measurement. (F) C57Bl/6J mice were fed with chow containing vehicle (water) or NR at 400 mg/kg/day (n=8 mice per group). After one week, mitochondria were isolated from their livers to measure NAD+ content. (G) HEK293T cells were treated with either PBS (as Vehicle) or 0.5 mM of NR for 24 hrs. Then mRNA and protein was extracted to measure Nampt levels by RT-qPCR and western blot, respectively. (H) HEK293T cells were treated with either PBS (as Vehicle) or 0.5 mM of NR for 24 hrs. Then protein homogenates were obtained to test global PARylation and PARP-1 levels. Throughout the figure, all values are presented as mean +/− SD. * indicates statistical significant difference vs. respective vehicle group at P < 0.05. Unless otherwise stated, the vehicle groups are represented by white bars, and NR groups are represented by black bars.

Given the existence of different cellular NAD+ pools and the relevance of mitochondrial NAD+ content for mitochondrial and cellular function (Yang et al., 2007a), we also analyzed whether NR treatment would affect mitochondrial NAD+ levels. In contrast to what has been observed with other strategies aimed to increase NAD+ bioavailability, such as PARP inhibition (Bai et al., 2011a), we found that mitochondrial NAD+ levels were enhanced in cultured cells (Fig.1E) and mouse liver (Fig.1F) after NR supplementation.

To further solidify our data, we also wondered whether the enhanced NAD+ levels upon NR treatment could derive from alterations in the NAD+ salvage pathway or PARP activity. However, we could not see any change in Nampt mRNA or protein content in response to NR treatment (Fig.1G). Similarly, PARP activity and PARP-1 content were not affected by NR (Fig.1H). Altogether, these results suggest that NR increases NAD+ by direct NAD+ biosynthesis rather than by indirectly affecting the major NAD+ salvage (Nampt) or consumption (PARPs) pathways. Importantly, this increase in NAD+ was not linked to changes in cellular glycolytic rates or ATP levels (data not shown), which would be expected if NAD+/NADH ratios had been altered to the point of compromising basic cellular functions.

NR treatment enhances SIRT1 and SIRT3 activity

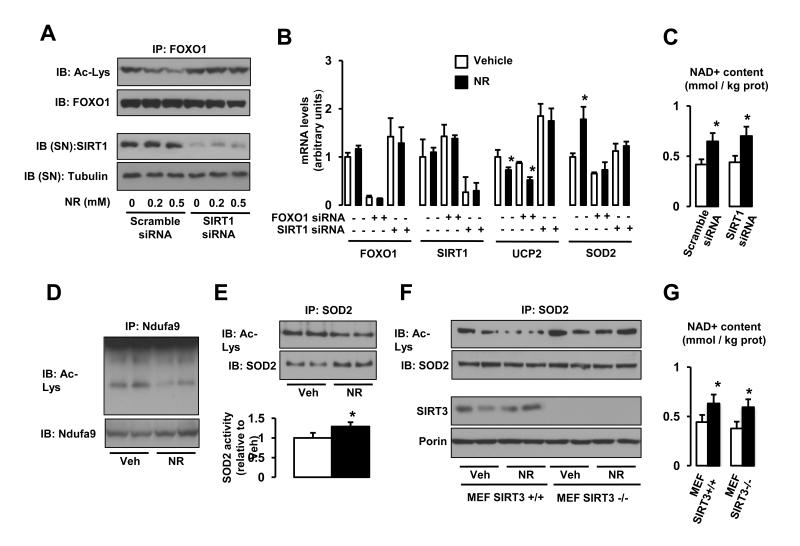

The ability of NR to increase intracellular NAD+ levels both in vivo and in vitro prompted us to test whether it could activate sirtuin enzymes. Confirming this hypothesis, NR dose-dependently decreased the acetylation of FOXO1 (Brunet et al., 2004) in a SIRT1-dependent manner (Fig 2A). This deacetylation of FOXO1 by SIRT1 upon NR treatment resulted in its transcriptional activation, leading to higher expression of target genes, such as Gadd45, Catalase, Sod1 and Sod2 (Fig.S1) (Calnan and Brunet, 2008). The lack of changes in SIRT1 protein levels upon NR treatment (Fig.2A) suggests that NR increases SIRT1 activity by enhancing NAD+ bioavailability. The higher SIRT1 activity in NR-treated cells was supported by mRNA expression analysis. Consistent with SIRT1 being a negative regulator of Ucp2 expression (Bordone et al., 2006), NR decreased Ucp2 mRNA levels (Fig.2B). Importantly, knocking down Sirt1 prevented the action of NR on Ucp2 expression (Fig.2B). Similarly, the higher expression of a FOXO1 target gene, Sod2, upon NR treatment was also prevented by the knockdown of either Foxo1 or Sirt1 (Fig.2B). This suggested that NR leads to a higher Sod2 expression thought the activation of SIRT1, which then deacetylates and activates FOXO1. Importantly, the knock-down of SIRT1 did not compromise the ability of NR to increase intracellular NAD+ content, indicating that NR uptake and metabolism into NAD+ is not affected by SIRT1 deficiency (Fig.2C).

Figure 2. Nicotinamide Riboside supplementation increases sirtuin activity in cultured mammalian cells.

(A) HEK293T cells were transfected with a pool of either scramble siRNAs or SIRT1 siRNAs. After 24 hrs, cells were treated with vehicle (PBS) or NR at the concentrations indicated, and, after an additional 24 hrs, total protein extracts were obtained. FOXO1 acetylation was tested after FOXO1 immunoprecipitation (IP) from 500 μg of protein, while tubulin and SIRT1 levels were evaluated in the supernatant of the IP. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with a pool of either scramble siRNAs, FOXO1 siRNAs or SIRT1 siRNAs. After 24 hrs, cells were treated with NR (0.5 mM; black bars) or vehicle (PBS; white bars) for additional 24 hrs. Then total mRNA was extracted and the mRNA expression levels of the markers indicated was evaluated by qRT-PCR. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with a pool of either scramble siRNAs, FOXO1 siRNAs or SIRT1 siRNAs. After 24 hrs, cells were treated with NR (0.5 mM; black bars) or vehicle (PBS; white bars) for additional 24 hrs. Then acidic extracts were obtained to measure intracellular NAD+ levels. (D-E) HEK293T cells were treated with NR (0.5 mM) or vehicle (PBS) for 24 hrs and total protein extracts were obtained to measure (D) Ndufa9 or (E) SOD2 acetylation after IP. The extracts were also used to measure SOD2 activity (E, bottom panel). (F-G). SIRT3+/+ and SIRT3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were treated with NR (0.5 mM) or vehicle (PBS) for 24 hrs and either (F) total extracts to test SOD2 acetylation were obtained or (G) acidic extracts were used to measure intracellular NAD+ content. Throughout the figure, all values are presented as mean +/− SD. * indicates statistical significant difference vs. respective vehicle group at P < 0.05. Unless otherwise stated, the vehicle groups are represented by white bars, and NR groups are represented by black bars. This figure is complemented by Fig.S1

In line with the increase in mitochondrial NAD+ levels (Fig.1E-F) and the potential consequent activation of mitochondrial sirtuins, NR also reduced the acetylation status of Ndufa9 and SOD2 (Fig.2D and 2E, respectively), both targets for SIRT3 (Ahn et al., 2008; Qiu et al., 2010). SOD2 deacetylation has been linked to a higher intrinsic activity. In line with these observations, NR treatment enhanced SOD2 activity (Fig.2E). To ensure that NR-induced SOD2 deacetylation was consequent to SIRT3 activation, we used mouse embryonary fibroblast (MEFs) established from SIRT3 KO mice. The absence of SIRT3 was reflected by the higher basal acetylation of SOD2 (Fig.2F). Importantly, NR was unable to decrease the acetylation status of SOD2 in SIRT3−/− MEFs (Fig.2F), despite that NAD+ levels increased to similar levels as in SIRT3+/+ MEFs (Fig.2G). These results clearly indicate that NR triggers SIRT3 activity, probably by increasing mitochondrial NAD+ levels, inducing the concomitant deacetylation of its mitochondrial targets. Strikingly, not all sirtuins were affected by NR, as the acetylation of tubulin, a target of the cytoplasmic SIRT2 (North et al., 2003), was not altered (data not shown).

NR supplementation enhances energy expenditure

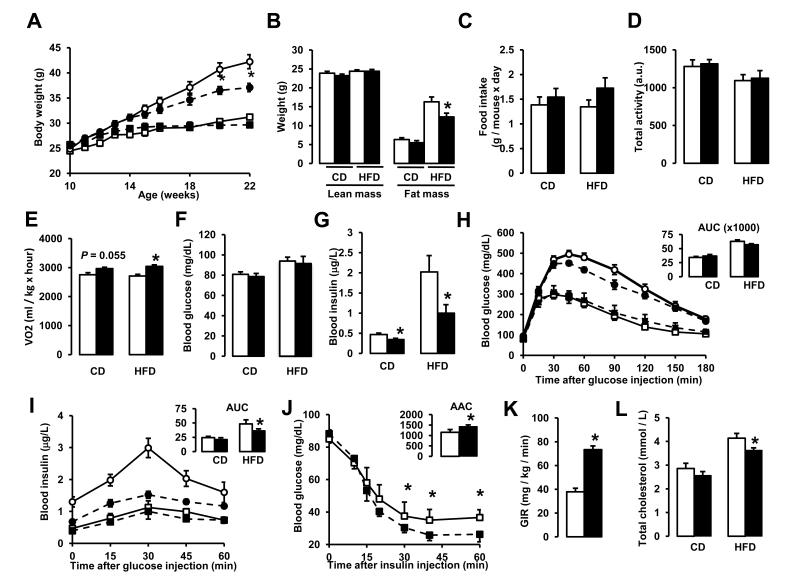

Given the promising role of sirtuins to protect against metabolic disease, we next evaluated the effects of long-term NR administration in vivo. We fed 10-week-old male C57Bl/6J mice with either chow (CD) or high-fat diet (HFD), supplemented or not with NR at 400 mg/kg/day. While NR had no effect on the body weight (BW) on CD, HFD-induced body weight gain was significantly attenuated by NR (Fig.3A), due to reduced fat mass (Fig.3B). This was visibly translated into a significant lower weight of the epididymal depot in NR-fed mice (Fig.S2A). Importantly, this was not due to redistribution of lipids to other tissues (Fig.S2A), most notably to liver, which actually contained 40% less triglycerides (Fig.S2B).

Figure 3. NR supplementation prevents diet-induced obesity by enhancing energy expenditure and reduces cholesterol levels.

10-week-old C57Bl/6J mice were fed with either chow (CD) or high fat diet (HFD) mixed with either water (as vehicle) or NR (400 mg/kg/day) (n=10 mice per group). (A) Body weight evolution was monitored during 12 weeks. (B) Body composition was evaluated after 8 weeks of diet through Echo-MRI. (C-E) Food intake, activity and VO2 were evaluated using indirect calorimetry. (F-G) Blood glucose and insulin levels were measured in animals fed with their respective diets for 16 weeks after a 6 hr fast. (H-I) After 10 weeks on their respective diets (CD = squares; HFD = circles) an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test was performed in mice that were fasted overnight. At the indicated times blood samples were obtained to evaluate either (H) glucose or (I) insulin levels. Areas under the curve are shown at the top-right of the respective panels. (J) Insulin tolerance tests were performed on either CD or CD-NR mice (4 weeks of treatment). At the indicated times, blood samples were obtained to evaluate blood glucose levels. The area above the curve is shown at the top-right of the panel. (K) Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps were performed on either CD or CD-NR mice (4 weeks of treatment). Glucose infusion rates (GIR) were calculated after the test. (L) Serum levels of total cholesterol were measured in animals fed with their respective diets for 16 weeks, after a 6 hr fast. Throughout the figure, white represent the vehicle group and black represent the NR-supplemented mice. All values are presented as mean +/− SD. * indicates statistical significant difference vs. respective vehicle treated group. This figure is complemented by Fig.S2

The reduced body weight gain of NR-fed mice upon HFD was not due to reduced food intake, as NR-fed mice actually had a tendency to eat more, especially on HFD conditions (Fig.3C). Similarly, NR did not affect the activity pattern of mice (Fig.3D), indicating that the lower BW on HFD was not consequent to different physical activity. Rather, the phenotype was due to enhanced energy expenditure (EE). Mice on CD had a marked tendency to display higher O2 consumption rates when fed with NR, and this tendency became clearly significant under HFD conditions (Fig.3E). Of note, NR-fed mice became more flexible in their use of energy substrates, as reflected in the higher amplitude of the changes in RER between feeding and fasting periods (Fig.S2C) in CD conditions. Altogether, these results indicate that NR lowers HFD-induced BW gain by enhancing EE.

From a metabolic perspective, NR- and vehicle-fed mice had similar fasting blood glucose levels in either CD or HFD conditions (Fig.3F). However, fasting insulin levels were much lower in NR-supplemented mice (Fig.3G). This lower insulin/glucose ratio is indicative of insulin sensitization after NR administration. This speculation was further supported by glucose tolerance tests. NR promoted a slight, albeit not significant, improvement in glucose tolerance (Fig.3H) in mice fed a HFD, accompanied by a robust reduction in insulin secretion (Fig.3I). Therefore, NR-fed mice on HFD display a better glucose disposal with lower insulin levels. In order to conclusively establish whether NR fed mice were more insulin sensitive, we performed insulin tolerance tests and hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps on CD and CD-NR mice. We chose not to perform this analysis on the HFD groups in order to avoid the possible influence of differential BW. Glucose disposal upon insulin delivery was largely enhanced in NR-fed mice (Fig.3J). In agreement, mice supplemented with NR required an almost 2-fold higher glucose infusion rate to maintain euglycemia in hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps (Fig.3K). Together, these observations unequivocally demonstrate that NR-fed mice are more insulin-sensitive. Furthermore, NR partially prevented the increase in total (Fig.3K) and LDL cholesterol levels (Fig.S2D) induced by HFD, even though HDL-cholesterol levels were unaffected (Fig.S2E). The amelioration of cholesterol profiles is fully in line with previous observations from the use of other NAD+ precursors, such as NA (Houtkooper et al., 2010).

NR enhances the oxidative performance of skeletal muscle and brown adipose tissue

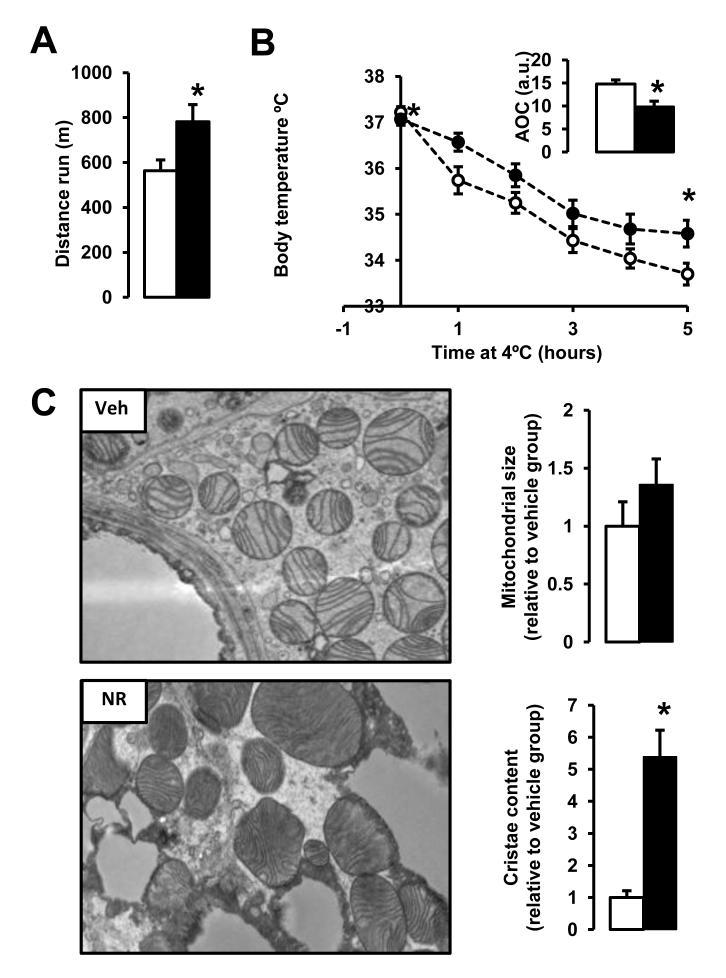

NR-fed mice had a clear tendency to display a better endurance performance than vehicle fed mice (Fig.S3A). This tendency was significantly accentuated upon HFD (Fig.4A), suggesting an enhanced muscle oxidative performance. Similarly, NR-fed mice, both on CD and HFD, showed enhanced thermogenic capacity, as manifested in the ability to maintain body temperature during cold exposure (Fig,S3B and Fig.4B). The latter observation hints toward an improvement in brown adipose tissue (BAT) oxidative performance. To gain further insight into the ability of BAT and muscle to enhance their oxidative performance, we performed some histological analysis. Gastrocnemius muscles from NR mice displayed a more intense SDH staining than their vehicle-fed littermates, indicating a higher oxidative profile (data not shown). Electron microscopy revealed that mitochondria in BAT of NR-fed mice, despite not being significantly larger, had more abundant cristae (Fig.4C), which has been linked to increased respiratory capacity (Mannella, 2006). Altogether, the above results suggest that NR supplemented mice display a higher oxidative capacity due to enhanced mitochondrial function.

Figure 4. NR enhances skeletal muscle and BAT oxidative function.

10-week-old C57Bl/6J mice were fed a high fat diet (HFD) mixed with either water (as vehicle; white bars and circles) or NR (400 mg/kg/day; black bars and circles) (n=10 mice per group). (A) An endurance exercise test was performed using a treadmill in mice fed with either HFD or HFD-NR for 12 weeks. (B) A cold-test was performed in mice fed with either HFD or HFD-NR for 9 weeks. The area over the curve (AOC) is shown on the top right of the graph. (D) Electron microscopy of the BAT was used to analyze mitochondrial content and morphology. The size and cristae content of mitochondria was quantified as specified in methods. Throughout the figure, all values are shown as mean +/− SD. * indicates statistical significant difference vs. vehicle supplemented group at P< 0.05. This figure is complemented by Fig.S3

Chronic NR feeding increases NAD+ in vivo in a tissue-specific manner

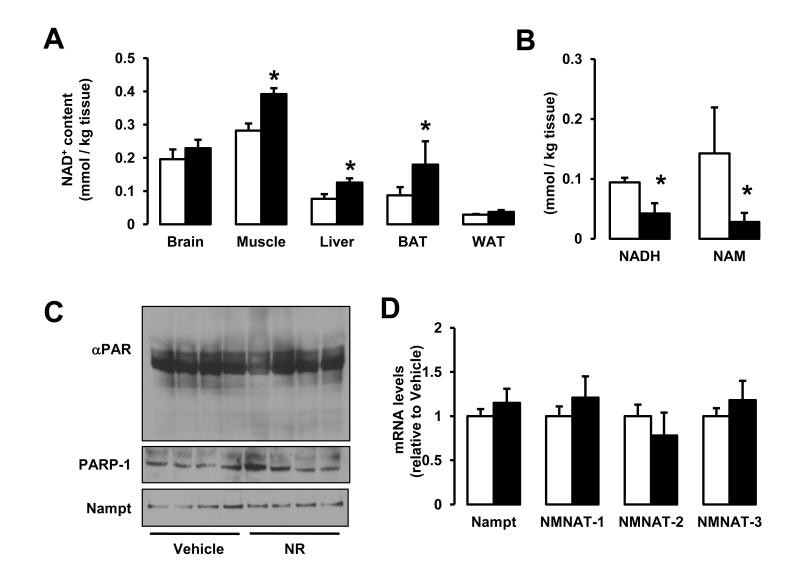

We next wondered how chronic NR feeding would affect NAD+ metabolism in mice. Chronic NR supplementation increased NAD+ levels in both CD (Fig.S4A) and HFD (Fig.5A) conditions in some tissues, including liver and muscle, but not in others, such as brain or white adipose tissue (WAT). Interestingly, NAD+ was also higher in the BAT of NR-fed mice, but only on HFD (Fig.5B and Fig.S4A). These differences could be due to the differential expression of NRKs in tissues. NRKs initiate NR metabolism into NAD+ (Houtkooper et al., 2010). There are two mammalian NRKs: NRK1 and NRK2 (Bieganowski and Brenner, 2004). While we found NRK1 expressed ubiquitously (Fig.S4B), NRK2 was mainly present in cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues, as previously described (Li et al., 1999), but also detectable in BAT and liver (Fig.S4C), in line with the better ability of these tissues to respond to NR.

Figure 5. Chronic NR supplementation increases plasma and intracellular NAD+ content in a tissue-specific manner.

Tissues from C57Bl/6J mice were collected after 16 weeks of HFD supplemented with either water (as vehicle; white bars) or NR (400 mg/kg/day; black bars). (A) NAD+ levels were measured in acidic extracts obtained from different tissues. (B) NADH and NAM levels were measured in gastrocnemius muscle. (C) Quadriceps muscle protein homogenates were obtained to test global PARylation, PARP-1 and Nampt protein levels. (D) Total mRNA was isolated from quadriceps muscles and the mRNA levels of the markers indicated were measured by RT-qPCR. Throughout the figure, all values are expressed as mean +/− SD. * indicates statistical significant difference vs. respective vehicle treated group.

We also tested whether the increase in NAD+ would be concomitant to changes in other NAD+ metabolites. Strikingly, NADH and nicotinamide (NAM) levels were largely diminished in muscles from NR-fed mice (Fig.5B), indicating that NR specifically increases NAD+, but not necessarily other by-products of NAD+ metabolism. We analyzed in vivo whether the activity of major NAD+ degrading enzymes or the levels of Nampt could also contribute to the increase in NAD+ after chronic NR supplementation. As previously observed in HEK293T cells (Fig.1G-H), PARP-1 levels and global PARylation were similar in muscle (Fig.5C) and livers (Fig.S4D) from NR- and vehicle-fed mice, indicating that the enhanced NAD+ content cannot be explained by differential NAD+ consumption through PARP activity. Nampt mRNA (Fig.5D) and protein (Fig.5C, Fig.S4E and data not shown) levels were also similar in NR and vehicle fed mice, suggesting that NAD+ salvage pathways do not explain the differences in NAD+ levels. We furthermore could not detect differences in mRNA expression of the different NMN adenylyltransferase (NMNAT) enzymes (Fig.5D). Altogether, these results reinforce the notion that the higher NAD+ levels observed in tissues from NR-fed mice is consequent to an increase in direct NAD+ synthesis from NR.

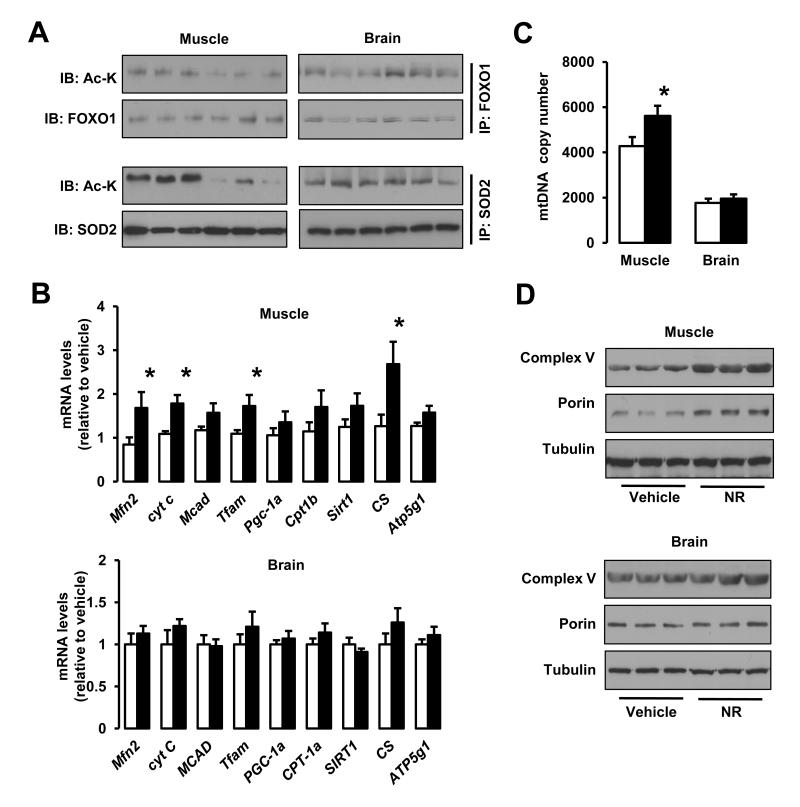

NR enhances sirtuin activity in vivo

Higher NAD+ levels were also accompanied by higher sirtuin activity in vivo. A prominent deacetylation of SIRT1 and SIRT3 targets (FOXO1 (Brunet et al., 2004) and SOD2 (Qiu et al., 2010), respectively) was observed in the skeletal muscle, liver and BAT, where NAD+ content was induced by NR, but not in brain and WAT, where NAD+ levels were unaffected by NR supplementation (Fig.6A and Fig.S5A). We also evaluated PGC-1α acetylation as a second readout of SIRT1 activity (Rodgers et al., 2005). We were unable to detect PGC-1α in total lysates from WAT or brain (Fig.S5B), but in muscle, liver and BAT PGC-1α was deacetylated upon NR treatment (Fig.S5C). These observations highlight how NR can only induce sirtuin activity in tissues where NAD+ accumulates. Like in cultured cells, we could not detect changes in the acetylation status of the SIRT2 target tubulin (data not shown), suggesting either that increasing NAD+ might not affect the activity of all sirtuins equally, that the increase is only compartment-specific or that additional regulatory elements, like class I and II HDACs, also contribute to tubulin acetylation status.

Figure 6. NR stimulates sirtuin activity in vivo and enhances mitochondrial gene expression.

Tissues from C57Bl/6J mice were collected after 16 weeks of HFD supplemented with either water (as vehicle; white bars) or NR (400 mg/kg/day; black bars). (A) Total protein extracts were obtained from quadriceps muscle and brain indicated to evaluate the acetylation levels of FOXO1 and SOD2 through immunoprecipitation assays, using 1 and 0.5 mg of protein, respectively. (B) Total mRNA from quadriceps muscle and brain was extracted to measure the abundance of the markers indicated by RT-qPCR. (C) Mitochondrial DNA content was measured in DNA extracted from quadriceps muscle and brain. The results are expressed a mitochondrial copy number relative to genomic DNA (D) The abundance of mitochondrial marker proteins in 20 μg of protein from total quadriceps muscle and brain lysates. Throughout the figure, all values are shown as mean +/− SD. * indicates statistical significant difference vs. vehicle supplemented group at P< 0.05. This figure is complemented by Fig.S4

In line with the changes in acetylation levels of PGC-1α, a key transcriptional regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, we could observe either an elevated expression or a strong tendency towards an increase (P < 0.1) of nuclear genes encoding transcriptional regulators of oxidative metabolism (Sirt1, PGC-1α, mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam)) and mitochondrial proteins (Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), Cytochrome C (Cyt C), Medium Chain Acyl-coA Dehydrogenase (MCAD), Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1b (CPT-1b), Citrate Synthase (CS) or ATP synthase lipid binding protein (ATP5g1)) in quadriceps muscles from NR-fed mice (Fig.6B). Conversely, in brain, where NAD+ and sirtuin activity levels were not affected by NR feeding, the expression of these genes was not altered (Fig.6B). Consistently also with enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial DNA content was increased in muscle, but not in brain from NR-fed mice (Fig.6C). Finally, mitochondrial protein content also confirmed that mitochondrial function was only enhanced in tissues in which NAD+ content was increased (Fig.6D and Fig.S5D). This way, while muscle, liver and BAT showed a prominent increase in mitochondrial proteins (Complex V - ATP synthase subunit α and porin), such change was not observed in brain or WAT. Altogether, these results suggest that NR feeding increases mitochondrial biogenesis in a tissue-specific manner, consistent with the tissue-specific nature of the increases in NAD+ and sirtuin activity observed in NR-fed mice. The higher number of mitochondria, together with the different morphological mitochondrial profiles found in NR-fed mice (Fig.4C) would contribute to explain the higher oxidative profile, energy expenditure and protection against metabolic damage observed upon NR feeding.

DISCUSSION

While increased NAD+ levels in response to NR supplementation were already reported in yeast (Belenky et al., 2007; Bieganowski and Brenner, 2004) and cultured human cells (Yang et al., 2007b), we extend these observations to a wide range of mammalian cell lines and demonstrate that NR supplementation also enhances NAD+ bioavailability in mammalian tissues. Also, our work provides evidence that the increase in NAD+ after NR administration stimulates the activity of mammalian sirtuins. This further supports the role of sirtuins as a family of proteins whose basal activity can be largely modulated by NAD+ availability (Houtkooper et al., 2010).

The fact that the activity of both SIRT1 and SIRT3 are positively regulated by NR both in vitro and in vivo favours the hypothesis that the increase in NAD+ promoted by NR affects, at least, the mitochondrial and the nuclear compartments. This is a key difference compared to other strategies that boost intracellular NAD+ levels. For example, Parp-1 knock-out mice show a two-fold increase in intracellular NAD+, yet SIRT3 activity is not affected (Bai et al., 2011b). Given that PARP-1 is a nuclear enzyme, it is tempting to hypothesize that, in the Parp-1 knockout mice, the increase in NAD+ is mainly confined to the nucleus, while the NR-induced increase in NAD+ levels, despite being more discrete in amplitude, reaches different subcellular compartments.

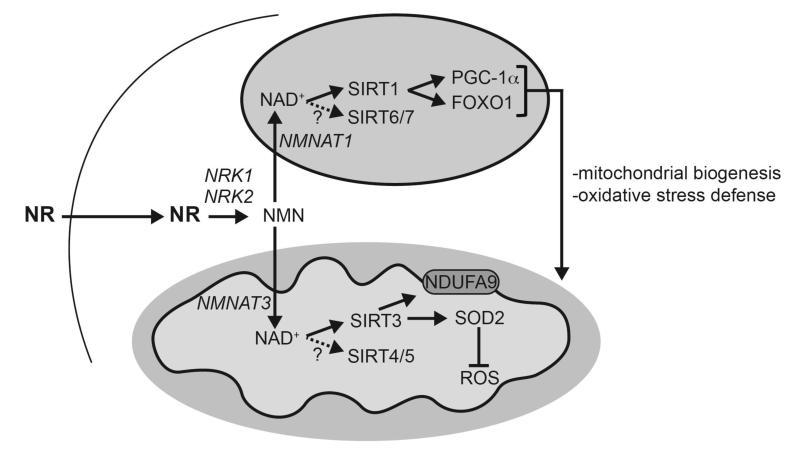

The inability of NR to activate GPR109A illustrates how NR provides an alternative way to increase NAD+ and ameliorate metabolic homeostasis in the absence of the undesirable effects seen with NA. Since NR does not activate GPR109A, we speculate that NR reduces cholesterol levels through the activation of SIRT1 in liver, which influences the activity of a number of transcription factors and cofactors linked to cholesterol homeostasis (Kemper et al., 2009; Li et al., 2007; Shin et al., 2003; Walker et al., 2010). Interestingly, the mechanism of action of NA on VLDL/LDL and hepatic metabolism is not clear, as GPR109A is not expressed in the liver (Tunaru et al., 2003). Our data raise the possibility that NA, like NR, achieves such effects by elevating NAD+ levels, activating SIRT1 and its downstream targets. However, future experiments will be required to verify this hypothesis. The activation of SIRT1 and SIRT3, impacting on targets such as PGC-1α, FOXOs and SOD2, also provides a likely explanation for the mitochondrial fitness and metabolic flexibility of NR-supplemented mice. In this sense, it is remarkable that while SIRT1 transgenic mice have some shared phenotypes with NR-treatment mice, such as protection against metabolic damage, there are also a number of discrepancies. For example, SIRT1 transgenics show similar body weight gain upon HFD to wild-type littermates (Pfluger et al., 2008). The differences between NR supplemented mice and SIRT1 trangenics can be explained by numerous reasons. First, NR affects different sirtuin activities; second, sirtuin expression does not necessarily correspond with sirtuin activity; third, NR actions are tissue-specific. Importantly, we should also consider that NR might trigger other actions unrelated to sirtuin activity that might also contribute to the beneficial effects of NR (Fig.7).

Figure 7. Schematic representation of the different actions of NR in metabolic homeostasis.

The scheme summarizes the hypothesis by which NR supplementation would increase NAD+ content in key metabolic tissues, leading to SIRT1 and SIRT3 activation and the deacetylation and modulation of the activity of key metabolic regulators. This model does not rule out the participation of additional mechanisms of action for NR to achieve its beneficial effects. Abbreviations can be found in the text and enzymes are indicated in italics.

In conclusion, our work shows that NR is a powerful supplement to boost NAD+ levels, activate sirtuin signalling and improve mitochondrial function, suggesting that this vitamin could be used to prevent and treat the mitochondrial decline that is a hallmark of many diseases associated with aging. Very recent work, showing that intraperitoneal administration of NMN could improve the metabolic damage induced by high fat feeding (Yoshino et al., 2011) further supports this concept. To date, however, only NR has been identified as a naturally occurring component of the human diet (Bieganowski and Brenner, 2004). Furthermore, NR protects against metabolic dysfunction at lower concentrations than those reported for NMN and we proved that it is effective after oral administration when mixed with food, which is in contrast to NMN which is injected intraperitoneally (Yoshino et al., 2011). So, how might NR and NMN biology intertwine and impact on NAD+ synthesis in mammalian physiology? Recent observations suggest that, at least for some cell types, NMN needs to be converted into NR through dephosphorylation performed by extracellular 5′-nucleotidases in order to penetrate into the cell (Nikiforov et al., 2011). Given that the presence of NMN in plasma is debated (Hara et al., 2011), the most likely scenario is that NR, rather than NMN, is the entity directly taken up by the cell, to then become metabolized in the cytosolic compartment to NMN. The lack of NRK1 and NRK2 in the mitochondrial compartment (Nikiforov et al., 2011) supports that NMN might act as the precursor entering the mitochondria or other compartments for further metabolism into NAD+ by the various NMNAT enzymes (see Fig.7 for a scheme).

Our data, combined with the evidence that other NAD+ precursors can improve age-related insulin resistance (Yoshino et al., 2011) and that NR increases yeast replicative lifespan (Belenky et al., 2007), therefore warrant future investigations to see if boosting NAD+ levels by NR supplementation might also improve the health- and lifespan of humans.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless stated otherwise. Nicotinamide Riboside was custom synthesized as previously described (Yang et al., 2007b) and was kindly provided by Amazentis and Merck Research Laboratories.

Animal experiments

8 weeks-old male C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from Charles River and powder chow (D12450B) and high fat (D12492) diets were from Research Diets Inc (New Brunswick, NJ, USA). 80 ml of water per kg of powder CD were used to make food pellets. 40 ml of water per kg of powder HFD were used to make food pellets. For NR, NMN and NA supplemented diets, the appropriate amount of these compounds was added to the water used to create the pellets, taking into account the differences in the daily intake of each diet. Mice were housed separately, had ad libitum access to water and food and were kept under a 12h dark-light cycle. Mice were fed with homemade pellets from 10 weeks of age. To make the pellets, the powder food was mixed with water (vehicle) or with NR. All animal experiments were carried according to national Swiss and EU ethical guidelines and approved by the local animal experimentation committee of the Canton de Vaud under license #2279.

Animal phenotyping

Mice were weighed and the food consumption was measured each week on the same day. Most clinical tests were carried out according to standard operational procedures (SOPs) established and validated within the Eumorphia program (Champy et al., 2008). Body composition was determined by Echo-MRI (Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX, USA) and oxygen consumption (VO2), respiratory exchange ratios (RER), food intake and activity levels were monitored by indirect calorimetry using the comprehensive laboratory animal monitoring system (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). Treadmill, cold tests and hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps were performed as described (Lagouge et al., 2006). Glucose and insulin tolerance was analyzed by measuring blood glucose and insulin following intraperitoneal injection of 2 g/kg glucose or 0.25 U insulin/kg, respectively, after an overnight fast. Plasma insulin was determined in heparinized plasma samples using specific ELISA kits (Mercodia). All animals were sacrificed at 13:00, after a 6 hr fast, using CO2 inhalation. Blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes and plasma was isolated after centrifugation. All plasma parameters were measured using a Cobas c111 (Roche Diagnostics). Tissues were collected upon sacrifice and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Histology and microscopy

Succinate dehydrogenase staining and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed as described (Bai et al., 2011b). Mitochondrial size and cristae content was analyzed as previously described (St-Pierre et al., 2003).

Cell culture and transfection

Murine C2C12 myoblasts were grown and differentiated into myotubes as described (Canto et al., 2009). Murine Hepa1.6 and human HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM (4,5 g/l glucose, 10% FCS). Human FOXO1 and SIRT1 siRNAs were obtained from Dharmacon (Thermo Scientific) and used following the instructions from the manufacturer. SIRT3 MEFs were established according to standard techniques (Picard et al., 2002) from conditional SIRT3−/− mice, whose generation will be described separately (Fernandez-Marcos et al., submitted). Deletion of the SIRT3 gene was induced via infection with adenovirus encoding for the Cre recombinase.

Gene expression and mitochondrial DNA abundance

RNA was extracted and quantified by qRT-PCR as described (Lagouge et al., 2006). The qPCR primers used have been previously described. Mitochondrial DNA abundance (mtDNA) was quantified as described (Lagouge et al., 2006) after isolating total DNA using a standard phenol extraction.

Immunoprecipitation, SDS-PAGE, Western blotting

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM KCl, EDTA 1 mM, NP40 1%, nicotinamide 5mM, Na-butyrate 1 mM, protease inhibitors pH7,4). Immunoprecipitation from cultured cells or tissue samples was performed exactly as described (Canto et al., 2009). For western blotting, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Anti-Acetyl-Lysine antibodies were from Cell Signalling; FOXO1 and SOD2 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SIRT1 and PGC-1α antibodies were from Millipore; Tubulin and Acetyl-tubulin antibodies were from Sigma Inc. Antibodies for mitochondrial markers were purchased from Mitosciences. Antibody detection reactions were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK).

NAD+, NADH and NAM determination

NAD+ levels were determined using a commercial kit (Enzychrom, BioAssays Systems, CA) and tissue samples were also measured by HPLC (Ramsey et al., 2009). Other NAD metabolites were determined as previously described (Yang and Sauve, 2006).

GPR109A – calcium mobilization assay

Ready-to-Assay™ GRP109A Nicotinic Acid Receptor Cells were used to measure calcium mobilization as specified by the manufacturer (Millipore). Calcium flux was determined using excitation at 340 and 380 nm in a fluorescence spectrophotometer (VictorX4, Perkin Elmer) in a 180 seconds time course, adding the ligand at 60 seconds. Internal validation was made using 0,1% Triton X-100 for total fluorophore release and 10 mM EGTA to chelate free calcium. Similarly, GPR109A specificity was internally validated using control cells devoid of GRP109A overexpression.

Liver triglyceride measurement

Liver triglycerides were measured from 20 mg of liver tissue using a variation of the Folch method, as described (Bai et al., 2011a).

Statistics

For the statistical analysis of the animal studies, all data was verified for normal distribution. To assess significance we performed Student’s t-test for independent samples. Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

NR efficiently increases NAD+ levels in mammalian cells and tissues

NR supplementation increases SIRT1 and SIRT3 activities.

NR largely prevents the detrimental metabolic effects of high-fat feeding.

NR enhances mitochondrial function and endurance performance

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Swiss National Science Foundation, the European Research Council Ideas programme (Sirtuins; ERC-2008-AdG231-118) and the Velux foundation. RHH has been supported by a Rubicon fellowship of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and by an AMC postdoc fellowship. EP is funded by the Academy of Finland. JA is the Nestle chair in energy metabolism. AAS received grants to support this research from the Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar Award 2007 and contract C023832 from NY State Spinal Cord Injury Board. The authors thank Robert Myers, Peter Meinke and Thomas Vogt at Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway and Charles Thomas at Amazentis, Lausanne, for the kind gift of NR, all the members of the Auwerx lab for inspiring discussions and Graham Knott of the BioEM facility at EPFL for EM imaging.

REFERENCES

- Ahn BH, Kim HS, Song S, Lee IH, Liu J, Vassilopoulos A, Deng CX, Finkel T. A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14447–14452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803790105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai P, Canto C, Brunyanszki A, Huber A, Szanto M, Cen Y, Yamamoto H, Houten SM, Kiss B, Oudart H, et al. PARP-2 regulates SIRT1 expression and whole-body energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 2011a;13:450–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai P, Canto C, Oudart H, Brunyanszki A, Cen Y, Thomas C, Yamamoto H, Huber A, Kiss B, Houtkooper RH, et al. PARP-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism through SIRT1 activation. Cell Metab. 2011b;13:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa MT, Soares SM, Novak CM, Sinclair D, Levine JA, Aksoy P, Chini EN. The enzyme CD38 (a NAD glycohydrolase, EC 3.2.2.5) is necessary for the development of diet-induced obesity. FASEB J. 2007;21:3629–3639. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8290com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky P, Racette FG, Bogan KL, McClure JM, Smith JS, Brenner C. Nicotinamide riboside promotes Sir2 silencing and extends lifespan via Nrk and Urh1/Pnp1/Meu1 pathways to NAD+ Cell. 2007;129:473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyo Z, Gille A, Kero J, Csiky M, Suchankova MC, Nusing RM, Moers A, Pfeffer K, Offermanns S. GPR109A (PUMA-G/HM74A) mediates nicotinic acid-induced flushing. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3634–3640. doi: 10.1172/JCI23626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieganowski P, Brenner C. Discoveries of nicotinamide riboside as a nutrient and conserved NRK genes establish a Preiss-Handler independent route to NAD+ in fungi and humans. Cell. 2004;117:495–502. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan KL, Brenner C. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: a molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:115–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordone L, Motta MC, Picard F, Robinson A, Jhala US, Apfeld J, McDonagh T, Lemieux M, McBurney M, Szilvasi A, et al. Sirt1 regulates insulin secretion by repressing UCP2 in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY, et al. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan DR, Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276–2288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto C, Auwerx J. Targeting sirtuin 1 to improve metabolism: all you need is NAD+? Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:166–187. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, Elliott PJ, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champy MF, Selloum M, Zeitler V, Caradec C, Jung B, Rousseau S, Pouilly L, Sorg T, Auwerx J. Genetic background determines metabolic phenotypes in the mouse. Mamm Genome. 2008;19:318–331. doi: 10.1007/s00335-008-9107-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara N, Yamada K, Shibata T, Osago H, Tsuchiya M. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase/visfatin does not catalyze nicotinamide mononucleotide formation in blood plasma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Jing E, Grueter CA, Collins AM, Aouizerat B, Stancakova A, Goetzman E, Lam MM, Schwer B, et al. SIRT3 Deficiency and Mitochondrial Protein Hyperacetylation Accelerate the Development of the Metabolic Syndrome. Mol Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtkooper RH, Canto C, Wanders RJ, Auwerx J. The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:194–223. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000a;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S, Johnson FB, Marciniak RA, McVey M, Park PU, Guarente L. Sir2: an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase that connects chromatin silencing, metabolism, and aging. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2000b;65:297–302. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpe F, Frayn KN. The nicotinic acid receptor--a new mechanism for an old drug. Lancet. 2004;363:1892–1894. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper JK, Xiao Z, Ponugoti B, Miao J, Fang S, Kanamaluru D, Tsang S, Wu SY, Chiang CM, Veenstra TD. FXR acetylation is normally dynamically regulated by p300 and SIRT1 but constitutively elevated in metabolic disease states. Cell Metab. 2009;10:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, Messadeq N, Milne J, Lambert P, Elliott P, et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell. 2006;127:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Mayne R, Wu C. A novel muscle-specific beta 1 integrin binding protein (MIBP) that modulates myogenic differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1391–1398. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhang S, Blander G, Tse JG, Krieger M, Guarente L. SIRT1 deacetylates and positively regulates the nuclear receptor LXR. Mol Cell. 2007;28:91–106. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannella CA. Structure and dynamics of the mitochondrial inner membrane cristae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov A, Dolle C, Niere M, Ziegler M. Pathways and subcellular compartmentation of NAD biosynthesis in human cells: from entry of extracellular precursors to mitochondrial NAD generation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:21767–21778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North BJ, Marshall BL, Borra MT, Denu JM, Verdin E. The human Sir2 ortholog, SIRT2, is an NAD+-dependent tubulin deacetylase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:437–444. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfluger PT, Herranz D, Velasco-Miguel S, Serrano M, Tschop MH. Sirt1 protects against high-fat diet-induced metabolic damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9793–9798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802917105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard F, Gehin M, Annicotte J, Rocchi S, Champy MF, O’Malley BW, Chambon P, Auwerx J. SRC-1 and TIF2 control energy balance between white and brown adipose tissues. Cell. 2002;111:931–941. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X, Brown K, Hirschey MD, Verdin E, Chen D. Calorie restriction reduces oxidative stress by SIRT3-mediated SOD2 activation. Cell Metab. 2010;12:662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey KM, Yoshino J, Brace CS, Abrassart D, Kobayashi Y, Marcheva B, Hong HK, Chong JL, Buhr ED, Lee C, et al. Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis. Science. 2009;324:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1171641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revollo JR, Korner A, Mills KF, Satoh A, Wang T, Garten A, Dasgupta B, Sasaki Y, Wolberger C, Townsend RR, et al. Nampt/PBEF/Visfatin regulates insulin secretion in beta cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab. 2007;6:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DJ, Campos JA, Gil G, Osborne TF. PGC-1alpha activates CYP7A1 and bile acid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50047–50052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J, Lin J, Krauss S, Tarr PT, Yang R, Newgard CB, Spiegelman BM. Bioenergetic analysis of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivators 1alpha and 1beta (PGC-1alpha and PGC-1beta) in muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26597–26603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunaru S, Kero J, Schaub A, Wufka C, Blaukat A, Pfeffer K, Offermanns S. PUMA-G and HM74 are receptors for nicotinic acid and mediate its anti-lipolytic effect. Nat Med. 2003;9:352–355. doi: 10.1038/nm824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AK, Yang F, Jiang K, Ji JY, Watts JL, Purushotham A, Boss O, Hirsch ML, Ribich S, Smith JJ, et al. Conserved role of SIRT1 orthologs in fasting-dependent inhibition of the lipid/cholesterol regulator SREBP. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1403–1417. doi: 10.1101/gad.1901210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Yang T, Baur JA, Perez E, Matsui T, Carmona JJ, Lamming DW, Souza-Pinto NC, Bohr VA, Rosenzweig A, et al. Nutrient-sensitive mitochondrial NAD+ levels dictate cell survival. Cell. 2007a;130:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Chan NY, Sauve AA. Syntheses of nicotinamide riboside and derivatives: effective agents for increasing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide concentrations in mammalian cells. J Med Chem. 2007b;50:6458–6461. doi: 10.1021/jm701001c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Sauve AA. NAD metabolism and sirtuins: metabolic regulation of protein deacetylation in stress and toxicity. AAPS J. 2006;8:E632–643. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino J, Mills KF, Yoon MJ, Imai S. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, a key NAD(+) intermediate, treats the pathophysiology of diet- and age-induced diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2011;14:528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.