Abstract

Objectives

The aims for this study were to determine the prevalence of sleep-bruxism among young children, explore child behavior problems that may be associated with sleep-bruxism, and identify relations among sleep-bruxism, health problems, and neurocognitive performance.

Methods

The current study was a retrospective analysis of parent report surveys, and behavioral and neurocognitive assessments. Parents of 1953 preschool and 2888 first grade children indicated their child’s frequency of bruxism during sleep. A subsample of preschool children (n = 249) had additional behavioral, as well as neurocognitive assessments. Among the subsample, parents also reported on their child’s health, and completed the Child Behavioral Checklist; children were administered the Differential Ability Scales, and Pre-Reading Abilities subtests of the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment.

Results

36.8% of preschoolers and 49.6% of first graders were reported to brux ≥ 1 time per week. Among the preschool subsample, bruxing was independently associated with increased internalizing behaviors (β = .17). Bruxism was also associated with increased health problems (β = .19), and increased health problems were associated with decreased neurocognitive performance (β = .22).

Conclusions

The prevalence of sleep-bruxism was high. A dynamic and potentially clinically relevant relation exists among sleep-bruxism, internalizing behaviors, health, and neurocognition. Pediatric sleep-bruxism may serve as a sentinel marker for possible adverse health conditions, and signal a need for early intervention. These results support the need for an interdisciplinary approach to pediatric sleep medicine, dentistry, and psychology.

Keywords: Parasomnia, Health, Dentistry, Behavior, Neurocognitive, Pediatrics

1. Introduction

Sleep-bruxism is a nonfunctional behavior characterized by the grinding or clenching of teeth; it typically occurs during non-rapid eye movement sleep stages N1 and N2, and is associated with arousals from sleep [1]. Sleep bruxism is typically identified by a family member who observes the stereotypic tooth-grinding sound, or by a dentist who recognizes abnormal occlusal wear [2]. The etiology of sleep-bruxism is considered multifactorial [3-5], consisting primarily of pathophysiologic factors (e.g., arousal response during sleep and immature masticatory neuromuscular system) with additional contributions from psychologic factors (e.g., stress and personality) and possibly morphologic factors (e.g., anatomy of the orofacial skeleton and occlusal alignment—there is, however, only little evidence for these specific factors) [6]. There were three aims for our retrospective analysis that utilized a convenience sample.

The first study aim was to determine the prevalence of parent-reported sleep-bruxism among large samples of preschool and first grade children. The reported prevalence of sleep-bruxism is highest during childhood, decreases across the life span and can resolve spontaneously [7]. The prevalence of childhood sleep-bruxism varies from 14% to 17% [1], 5–20% [8], 22% [9], 28–30% [10], and 38% [11]; however, prevalence rates may be underestimates since less common occurrences may not come to medical attention [12]. The reported prevalence of child sleep-bruxism ranges widely; large community-based samples of children could help clarify prevalence rates.

The second study aim was to explore behavior problems that may be associated with sleep-bruxism. Generally, parental reports of child sleep problems are associated with problematic child daytime behaviors [13]. Specific to child sleep-bruxism, children who brux showed more polysomnographically identified arousals from sleep, and have a tendency to demonstrate more internalizing, externalizing, somatic, oppositional defiant, and conduct problems when compared to age–sex matched controls [14]. Bruxism-associated sleep problems during childhood might lead to subsequent deleterious psychiatric problems. An eleven year longitudinal study among four year old children, indicated that sleep problems at age four predicted behavioral and emotional problems at age 15 [15]. Large sample studies that examine child behavior problems in association with sleep bruxism may help build a framework for clinicians to avert potentially adverse developmental trajectories among child bruxers.

The third study aim was to identify possible relations among sleep-bruxism with health problems and neurocognitive performance. Frequent arousals from sleep are common among child bruxers [14], and nocturnal arousals are collectively known as sleep fragmentation, which interrupts the integrity of the normal sleep cycle. Among children, greater sleep fragmentation is associated with increased fluctuations in neuroendocrine functioning, and there appears to be a link between poor sleep and poor health among children [16]. Additionally, children who are poor sleepers have worse immune function [17], and adult sleep-bruxers acquire significantly more medical attention than adult non-bruxers [18]. Furthermore, a generally accepted principal indicates that sleep problems (e.g., fragmentation [19], short sleep time [20]) among youth are associated with lower neurocognitive performance ([21]). In summary, children who demonstrate bruxism during sleep may be at risk for both adverse health and cognitive consequences; yet, further research is required to make this determination.

2. Methods

The current study was developed to examine several aspects of pediatric sleep-bruxism by utilizing data from a large sample of convenience. These retrospecitve analyses use data collected for two larger studies of healthy children [22]. Both studies were approved by the University of Louisville and Kosair Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent and child assent (for children ≥7 years) were administered prior to participation.

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from two populations in Jefferson County, Kentucky. One population attended Early Jump Start preschool and was a priori defined as a low income sample (N = 1953, M = 4.3 ± 6 [range: 2.5–6.9] years). The other population attended first grade classes at public schools, (N = 2888, M = 6.2 ± .5 [range: 3.0–8.6] years). All participants completed a parent report survey on their child’s sleep and health behaviors. Data from both of these full samples were separately examined to determine prevalence of parent reported sleep-bruxism.

Data from a subgroup of the preschool age children (N = 249, M = 4.5 ± .7 [range: 2.87–6.11] years) were also examined. Parents of these children completed a report of their child’s behavior, and children completed neurocognitive assessments. Data from the subgroup of preschool children were explored to identify which behaviors were most strongly associated with sleep-bruxism. Furthermore, a regression model was hypothesized and tested to examine the relations among sleep-bruxism with health problems and neuropsychological performance among this subgroup of pre-school-aged children.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sleep bruxism and health problems behaviors

Parent report is considered good screening method for identifying pediatric bruxism [4,6], but the report does rely heavily on the parents knowledge of sleep bruxism/tooth grinding noises and sleeping environment (e.g., co-sleeping) [2,23]. Parents completed a self report survey that probed a variety of their child’s sleep and health behaviors, which was specifically developed for the larger study (see [22]). For this study, the parent-report survey of child sleep behaviors included a sleep-bruxism item: “Does he/she grind his/her teeth during sleep?” Specifically for the larger study, the survey also included an item about snoring (the primary symptom of sleep-disordered breathing), “How often does your child snore during sleep?” Both sleep behavior items were followed with response options and corresponded with numerical codes of never (never in the past six months = 0), rarely (once a week = 1), occasionally (two times a week = 2), frequently (three–four times a week = 3), and almost always (more than four times a week = 4).

The survey also included nine health items with Yes (=1) or No (=0) response options: allergies, vision problems, poor appetite, ear infections, frequent cold or flu-like symptoms, hearing problems, poor growth, asthma, and constant runny nose. All health items were included. Items were parceled into three components[24,25], and each component functioned as an observed variable to form a health problems latent variable.

2.2.2. Behavioral problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) survey is a parent report instrument used to identify internalizing, externalizing, and total problem behaviors [26,27]. During the early study period, child behaviors were reported via the CBCL [26] for ages 4–18 (n = 78, M = 4.69 ± .62 years); later in the study, the CBCL [27] for ages 1.5–5 became available and was used thereafter (n = 135, M = 4.71 ± .71 years). Total problem behavior scores between early (M = 57.23 ± 11.74) and later (M = 59.49 ± 10.89) CBCL versions did not differ (F[1,211] = 1.93, p = .17, Hedge’s g = .20).

2.2.3. Neurocognitive performance

The Differential Ability Scales (DAS) is a battery of cognitive tests designed to measure verbal, reasoning, and spatial ability [28]. Assessments of verbal (verbal comprehension and naming vocabulary) and nonverbal ability (picture similarities, pattern construction, copying and early number concepts) were administered. The Pre-Reading Abilities subtests from the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment (NEPSY) were also administered to examine cognitive learning [29]. NEPSY sentence repetition and verbal fluency subsets were administered. The DAS and NEPSY were administered by doctoral level students qualified to administer neurocognitive assessments; they were blinded to subjects’ survey data. The DAS and NEPSY scales functioned as observed variables to form a neurocognitive performance latent variable.

2.2.4. Statistical analyses

Prevalence of parent reported bruxism was calculated separately for preschool and first grade children. Within each sample, chi-square analyses were used to calculate differences in frequency of sleep-bruxism by race/ethnicity (3 [race/ethnicity] × 5 [bruxism frequency]) and sex (2 [sex] × 5 [bruxism frequency]).

Using SPSS (version 18), a stepwise linear regression was calculated to explore which CBCL-based behavioral domains were most strongly associated with sleep-bruxism.

Structural regression models were calculated with AMOS 18 software. The ability of the regression models to reproduce similar results among another sample is described by standard model fit indices (Chi-square, Comparative Fit Index [CFI], and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA]). Structural regression models were fit according to the Maximum Likelihood Estimation Method; means and intercepts were estimated. Structural regression analysis permits assessment of hypothesized relations among latent (i.e. constructs described by observed variables that are measured to represent a certain domain) and observed (measured) variables while accounting for measurement error variances.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses

Child demographic characteristics are shown on Table 1. Both preschooler, the preschooler subsample, and first grader samples were missing data as indicated on Table 1; additionally, 14.46% of the preschool subsample was missing the CBCL. There were no significant differences in sex, ethnicity, or parental education among the total sample and the subsample (n = 249) of preschool children. However, there was a small difference in the bruxing rate between the total sample and subsample (F[1,1927] = 29.68, p < .001, Hedge’s g = 0.38) of preschool children; the subsample was reported to brux more frequently. The subsample of preschool children had a spectrum of sleep-disordered breathing symptoms (43.7 not at-risk [snore <3 times per-week], and 56.3% at-risk [snore ≥3 times per-week]), specific for the larger study [22]. Sleep disordered breathing is a risk-factor for sleep bruxism [18]; therefore, we explored the relation between these two variables within our sample. Sleep bruxism did not differ among children who were identified as at-risk and not at-risk for sleep disordered breathing (p = .08, g = .18); nor were frequency of sleep bruxism and snoring correlated (p = .10, r = .11). Since there was no statistically significant difference or relation among these groups, they were combined to calculate the structural regression.

Table 1.

Prevalence of sleep bruxism by parental report by sex and racial/ethnic background for preschool and first grade children.

| Characteristic | n (Age ± SD) | Never (0) (%) | Rarely (1)(%) | Occasionally (2) (%) | Frequently (3) (%) | Almost always (4) (%) | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preschoolers | Total | 1953 (4.3 ±0.6) | 63.2 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 0.8 ±1.3 |

| Female | 899 (4.2 ± 0.6) | 65.2 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 0.8 ±1.2 | |

| Male | 963 (4.3 ± 0.6) | 61.4 | 10.7 | 13.1 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 0.9 ±1.3 | |

| †White | 865 (4.3 ± 0.6) | 57.0 | 13.3 | 14.5 | 8.8 | 6.5 | 1.0 ±1.3 | |

| †African | 749 (4.2 ± 0.6) | 70.5 | 8.7 | 9.8 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 0.7 ±1.2 | |

| American | ||||||||

| †Other/biracial | 225 (4.3 ± 0.6) | 63.6 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 6.7 | 8.0 | 0.8 ±1.3 | |

| Preschoolers: subsample | Total | 249 (4.5 ± 0.7) | 47.9 | 16.1 | 15.3 | 5.1 | 15.7 | 1.3 ±1.5 |

| First graders | Total | 2888 (6.2 ± 0.0) | 50.4 | 15.4 | 13.7 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 1.2 ±1.4 |

| ‡Female | 1307 (6.2 ±0.5) | 53.3 | 14.6 | 13.5 | 8.4 | 10.1 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | |

| ‡Male | 1527 (6.1 ±0.5) | 47.8 | 16.0 | 13.8 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 1.2 ±1.4 | |

| White | 1934 (6.2 ±0.5) | 50.5 | 14.7 | 14.1 | 9.7 | 11.0 | 1.2 ±1.4 | |

| African | 545 (6.2 ± 0.5) | 47.9 | 18.2 | 12.7 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 1.2 ±1.4 | |

| American | ||||||||

| Other/biracial | 247 (6.2 ± 0.6) | 51.0 | 14.6 | 13.4 | 10.5 | 9.3 | 1.1 ± 1.4 |

Note:

a significant difference in bruxism frequency by race/ethnicity (differences reported in-text)

a significant difference in bruxism frequency by sex (differences reported in-text). “Never” = never in the past six months, “Rarely” = once a week, “Occasionally” = two times a week, “frequently” = three-four times a week, “almost always” = more than four times a week, “average” = the average score (0–4) within the respective characteristic. Overall prevalence of parent-reported bruxism can be calculated by subtracting values indicated as “never” from 100%. Preschoolers: 3.3% missing age, 3.6% missing sex, 4.9% missing race/ethnicity, 1.2% missing bruxism frequency; preschool subsample: 4.8% missing age, 6.4% missing sex, 7.6% missing race/ethnicity, 5.6% missing bruxism frequency; first graders: 1.5% missing age, 0.4% missing sex, 4.4% missing race/ethnicity, 1.6% missing bruxism frequency.

Preschoolers: 34.8% of mothers and 28.5% of fathers obtained a college education or higher.

First graders: 63.2% of mothers and 47.4% of fathers obtained a college education or higher.

3.2. Prevalence of sleep-bruxism

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the parent reported prevalence of sleep-bruxism among the samples of preschool and first grade children. This table also shows differences in sleep bruxism frequencies by sex and race/ethnicity for both preschool and first grade children.

Overall, 36.8% of preschoolers were reported to brux at least one night per week, and 6.7% were reported to brux more than four nights per week. Among preschoolers, there was a significant race/ethnicity effect on sleep-bruxism frequency χ2 (8, N = 1837) = 38.0, p < .0001, Cramer’s V = .10. The largest discrepancy indicated that African American children were reported to “never” brux more than other racial/ethnic groups, whereas White children were reported to “never” brux less than other racial/ethnic groups. A simple comparison indicated a significant race/ethnicity effect on reported bruxism frequency among White and African American children χ2 (4, n = 1614) = 36.4, p < .0001, Cramer’s V = .08. The largest discrepancy indicated that African American children were reported to “never” brux more than White children. Simple comparisons did not indicate significant race/ethnicity effect on reported sleep-bruxism frequency among White (χ2 [4, n = 1088] = 6.2, p = .18, Cramer’s V = .08), or African American (χ2 [4, n = 972] = 3.99, p = .41, Cramer’s V = .06) children when compared to other/biracial children. There was not a significant sex effect on reported sleep-bruxism frequency (χ2 [4, N = 1862] = 7.1, p = .13, Cramer’s V = .06).

Overall, 49.6% of first graders were reported to brux at least one night per week, and 10.7% were reported to brux more than four nights per week. Among first graders, there was not a significant race/ethnicity effect on reported sleep-bruxism frequency χ2 (8, N = 2723) = 5.7, p = .68, Cramer’s V = .03; however, there was a significant sex effect χ2 (4, N = 2,834) = 11.2, p = .03, Cramer’s V = .06. The largest discrepancy in sleep-bruxism frequency by sex was that girls were reported to “never” brux more than boys.

3.3. Behavioral problems associated with sleep-bruxism

Among the preschool subsample, sleep-bruxism was most strongly associated with internalizing behaviors (R = .17, F[1,198] = 5.8, β = .17, p = 0.02). Externalizing behaviors (β = .16, p = .06) and total problem behaviors (β = .13, p = .21) were not associated with sleep-bruxism above and beyond internalizing behaviors.

3.4. Structural regression: sleep-bruxism, health problems, and neurocognitive performance

Although sleep-disordered breathing was not the purpose of this project, to explore effects, we initially analyzed bruxism differences between children at-risk for sleep disordered breathing (who were reported to snore three or more nights per week) and not at-risk (who were reported to snore two or fewer nights per week).

Next, a measurement model was calculated to examine the integrity of latent variables health problems and neurocognitive performance. Model fit and itemized correlations were acceptable (Tables 2a and 2b), therefore, the latent variables were entered into the regression model.

Table 2a.

Correlations among manifest health indicators that form the ‘health problems’ latent variable.

| Health: indicators | Health component 2 | Health component 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Health component 1 | .37** | .28** |

| Health component 2 | - | .34** |

Note:

p <.01.

Table 2b.

Correlations among manifest neurocognitive performance indicators that form the ‘neurocognitive performance’ latent variable.

| Neurocognitive performance: indicators |

DAS: non verbal |

NEPSY: sentence repetition |

NEPSY: verbal fluency |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAS: verbal | .54** | .46** | .46** |

| DAS: non verbal | - | .45** | .42** |

| NEPSY: sentence repetition |

- | - | .52** |

Note:

p < .01

the measurement model was adequately fit χ2 (14, n = 249) = 18.62, p = 0.18, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04 (0.00, 0.08). “Health Component 1” = totaled values across variables constant runny nose, poor growth, and poor appetite; “Health Component 2” = totaled values across variables frequent colds flus, ear infections, and hearing problems; “health component” = totaled values across variables allergies, asthma, and vision problems’; DAS = Differential Abilities Scales; NEPSY = Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment.

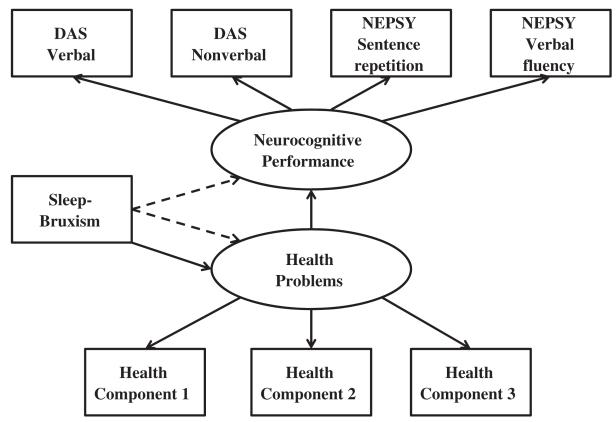

To examine the relations among sleep-bruxism with health problems and neurocognitive performance, a regression model was hypothesized. The hypothesized model was adequately fit (Fig. 1), and sleep-bruxism was significantly associated with health problems (β = .20), but not with neurocognitive performance (β = .07). Based on the hypothesis that sleep-bruxism would be associated with both health problems and neurocognitive performance, the hypothesized model was rejected and respecified to permit a statistical examination (Soble) of an indirect association between sleep-bruxism and ‘neurocognitive performance’. The respecified model was adequately fit and was retained (Fig. 1). Sleep-bruxism was associated with health problems and health problems was associated with neurocognitive performance; standardized parameter estimates for the retained regression model are indicated on Table 3. The Sobel test for mediation did not identify a significant indirect relation between sleep-bruxism and neurocognitive performance (Sobel = −1.49, p = 0.14).

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized (rejected) and respecified (retained) structural regression model that examined relations among the observed bruxism variable with health problems and neurocognitive performance latent variables. Note: The hypothesized regression model is represented by the dashed lines (only); bruxism was an observed exogenous variable that was regressed to the endogenous latent variables health problems and neurocognitive performance. The hypothesized, but rejected, regression model fit was adequate χ2 (n = 249) = 29.882, p = 0.053, CFI = 0.957, RMSEA = 0.048 (0.000, 0.079). The respecified, and retained, regression model is indicated by the solid lines (only); bruxism was an observed exogenous variable that was regressed to the endogenous latent variable health problems, which was regressed to the endogenous latent variable neurocognitive performance. The retained regression model fit was adequate χ2 (n = 249) = 26.326, p = 0.121, CFI = 0.971, RMSEA = 0.039 (0.000, 0.073). The Sobel statistic was calculated on the retained regression model to examine a possible indirect association between bruxism and neurocognitive performance.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and standardized parameter estimates for structural regression model among sleep bruxism (observed), ‘neurocognitive performance’ (latent), and ‘health problems’ (latent) variables.

| Variable | Descriptive statistics |

Parameter estimates |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Yes | Mean±SD | β | p Value | |

| *Health problems | ||||

| †Health component 1 | 0.56 | - | ||

| ‡Constant runny nose | 30.5% | |||

| ‡Poor growth | 7.1% | |||

| ‡Poor appetite | 24.3% | |||

| †Health component 2 | 0.67 | <.001 | ||

| ‡Frequent colds flus | 43.9% | |||

| ‡Ear infections | 44.5% | |||

| ‡Hearing problems | 8.9% | |||

| †Health component 3 | 0.55 | <.001 | ||

| ‡Allergies | 42.4% | |||

| ‡Asthma | 22.2% | |||

| ‡Vision problems | 9.7% | |||

| *Neurocognitive Performance | ||||

| †DAS: verbal | 88.5±14.9 | 0.70 | ||

| †DAS: non verbal | 95.3±20.9 | 0.68 | <.001 | |

| †NEPSY: sentence repetition | 8.9±3.0 | 0.72 | <.001 | |

| †NEPSY: verbal fluency | 8.4±3.0 | 0.70 | <.001 | |

| Structural model | ||||

| Sleep bruxism → health problems | 0.19 | =.03 | ||

| Health problems → neurocognitive performance |

−0.22 | =.04 | ||

Note. – Variables were not calculated because they were constrained in the model.

Latent variables in model

observed variable, bruxism was also an observed variable

parceled observed variables

- indicates a pathway in the structural regression. DAS = Differential Abilities Scales; NEPSY = Developmental Neuropsy-chological Assessment.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of parent reported sleep-bruxism that occurred at least once a week among preschool and first grade children was 36.8% and 49.6%, respectively. Among the preschool subsample, internalizing behaviors were associated with sleep-bruxism. Increased sleep-bruxism was associated with increased health problems and increased health problems was associated with decreased neurocognitive performance.

The frequency of sleep-bruxism that occurred at least once a week among preschool children approximately matched the highest child prevalence previously reported [11], while the community based first graders bruxed at a frequency that was 10% higher than the highest prevalence rate [11]. However, among pre-school and first grade children, the higher frequencies of sleep-bruxism (e.g., more than four times a week) were congruent with values previously reported (e.g., [1,8-10]). Notably, sleep-bruxism distinction and frequency is not equivalently described in all studies; thus, many epidemiological studies on sleep bruxism are not fully comparable. The current report of sleep-bruxism frequencies may serve as epidemiological data that represent low income pre-schoolers, as well as a community population of first grade children. Among preschoolers, White children were reported to brux more than African American children; to our knowledge, this is the first report of racial/ethnic differences in sleep-bruxism among young children. This result may reflect an actual difference in sleep-bruxism frequency between White and African American children; alternatively, it may reflect a greater awareness on the part of some parents. Sleeping proximity may play a role in such awareness, though we do not know of any data that shows a higher incidence of co-sleeping among these two groups at this age.

Among first graders, boys were reported to brux more often than girls. The sex difference in sleep-bruxism among first graders may be considered negligible due to the small effect. However, this finding is novel because it is contrary to recent sleep-bruxism prevalence reports among Brazillian girls and boys [30], and furthermore, because children typically do not demonstrate sex differences on temporomandibular disorders, oral parafunctions, or bruxism [1,31].

Among preschool children, internalizing behaviors (i.e. anxious, depressed, withdrawn, and somatic complaints) were independently associated with sleep-bruxism. This result is similar to a recent report that linked increased child sleep-bruxism to increased child mental health problems [10]. The presence of sleep-bruxism or internalizing behaviors may be used to mutually inform the presence of the other, as well as a potential trajectory for adverse conditions associated with them. For example, among adults, sleep-bruxism is associated with a multitude of adverse psychological symptoms [18,32,33]; child internalizing behaviors may be developmental precursors to psychological conditions that manifest in adulthood. Furthermore, parentally reported child sleep problems have been proposed to indicate a variety of problematic functional outcomes that include behavior and health [34].

As the frequency of sleep-bruxism increased, child health problems had increased. Sleep bruxism may serve as a behavioral indicator, or a sentinel marker, for possible adverse health conditions among children and may be a signal that early health care intervention is needed. For example, a recent report indicated that children who brux are 2.4 more likely to experience migraines than children who do not brux [9]. Additionally, as health problems increased, neurocognitive performance decreased. These results are supported by previous work, which indicates that children with either poor general or oral health are 1.4 times more likely to demonstrate poor/school performance; this ratio approximately doubles when the two conditions are endorsed together [35]. Despite evidence that healthy sleep enriches learning among children (see review [36]), sleep-bruxism was not directly, or indirectly associated with neurocognitive performance.

There are several methodological limitations within the current study. Although parentally reported sleep-bruxism is considered valid [4,6], and the health problems latent variable was a robust measure, future research may benefit from an objective measure of sleep-bruxism and a detailed exploration of its association with specific health conditions. The structural regression model was used to identify possible relations among sleep-bruxism, health problems and neurocognitive performance, therefore, causal pathways cannot be deduced.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, sleep-bruxism is a relatively common and observable behavior among preschool-aged and first grade children. Heightened sleep-bruxism frequency may serve as an indicator for concurrent, or possibly future, behavioral and health problems. Sleep-bruxism is a dynamic behavior that concerns medical, dental, and psychological health care domains and may be an important behavior to consider within a multidisciplinary health care context.

Acknowledgements

The authors report no conflicts of interest. Support was provided by: Department of Education Grant H324E011001 (DG), CDC Grant E11/CCE422081-01 (DG), and NIH Grant F32-HD053836 (HMD). The authors thank the families who participated in this study and the school administrators and teachers who facilitated data collection. Louise O’Brien, PhD, and Cheryl Holbrook, RPSGT, played significant roles in data collection. Jennifer Bruner, RPSGT, Carrie Klaus, RPSGT, SLEEP Catherine McCliment, MA, Troy Raffield, PhD, Jennifer Rutherford, PhD, Nigel Smith, PSGT, and Lisa Witcher, MS assisted with neurocognitive and/or CBCL data collection.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest associated with this article can be viewed by clicking on the following link: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2012.09.027.

References

- [1].American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Westchester (IL): 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bader G, Lavigne G. Sleep bruxism; an overview of an oromandibular sleep movement disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:27–43. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kato T, Montplaisir JY, Guitard F, Sessle BJ, Lund JP, Lavigne GJ. Evidence that experimentally induced sleep bruxism is a consequence of transient arousal. J Dent Res. 2003;82:284–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lavigne GJ, Huynh N, Kato T, Okura K, Adachi K, Yao D, et al. Genesis of sleep bruxism: motor and autonomic-cardiac interactions. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:381–4. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lobbezoo F, Naeije M. Bruxism is mainly regulated centrally, not peripherally. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28:1085–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barbosa TS, Miyakoda LS, Pocztaruk RL, Rocha CP, Gaviao MB. Temporomandibular disorders and bruxism in childhood and adolescence. review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:299–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Glaros AG. Bruxism. In: Mostofsky DI, Forgione AG, Giddon DB, editors. Behavioral dentistry. Wiley-Blackwell; 2006. pp. 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sheldon SH. The parasomnias. In: Sheldon SH, Ferber R, Kryger MH, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric sleep medicine. Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 305–15. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Arruda MA, Guidetti V, Galli F, Albuquerque RC, Bigal ME. Childhood periodic syndromes: a population-based study. Pediatr Neurol. 2010;43(6):420–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Renner AC, da Silva AA, Rodriguez JD, Simoes VM, Barbieri MA, Bettiol H, et al. Are mental health problems and depression associated with bruxism in children? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:277–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cheifetz AT, Osganian SK, Allred EN, Needleman HL. Prevalence of bruxism and associated correlates in children as reported by parents. J Dent Child. 2005;72:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Giglio P, Undevia N, Spire JP. The primary parasomnias. A review for neurologists. Neurologist. 2005;11:90–7. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000149970.67188.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Goodlin-Jones B, Tang K, Liu J, Anders TF. Sleep problems, sleepiness and daytime behavior in preschool-age children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:1532–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Herrera M, Valencia I, Grant M, Metroka D, Chialastri A, Kothare SV. Bruxism in children: effect on sleep architecture and daytime cognitive performance and behavior. Sleep. 2006;29:1143–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gregory AM, O’Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:964–71. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Pesonen AK, Pyhala R, Paavonen EJ, Feldt K, et al. Poor sleep and altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical and sympatho-adrenal-medullary system activity in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2254–61. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang MF. Sleep quality and immune mediators in asthmatic children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:222–9. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(09)60067-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ohayon MM, Li KK, Guilleminault C. Risk factors for sleep bruxism in the general population. Chest. 2001;119:53–61. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Dev. 2002;73:405–17. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Touchette E, Petit D, Seguin JR, Boivin M, Tremblay RE, Montplaisir JY. Associations between sleep duration patterns and behavioral/cognitive functioning at school entry. Sleep. 2007;30:1213–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].O’Brien LM. The neurocognitive effects of sleep disruption in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18:813–23. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Montgomery-Downs HE, O’Brien LM, Holbrook CR, Gozal D. Snoring and sleep-disordered breathing in young children: subjective and objective correlates. Sleep. 2004;27:87–94. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lavigne GJ, Rompre PH, Montplaisir JY. Sleep bruxism: validity of clinical research diagnostic criteria in a controlled polysomnographic study. J Dent Res. 1996;75:546–52. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Little TD, Nesselroade JR, Lindenberger U. On selecting indicators for multivariate measurement and modeling with latent variables: when “good” indicators are bad and “bad” indicators are good. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:192–211. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighting the merits. Struct Eq Model. 2002;9:151–73. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Achenbach TM. Integrative guide to the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; Burlington (VT): 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families; Burlington (VT): 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Elliott CD. The differential abilities scale. In: Flanagan DP, Harrison PL, editors. Contemporary intellectual assessment: theories, tests, and issues. The Guilford Press; New York: 2005. pp. 402–23. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Korkman M, Kirk U, Kemp S. NEPSY: a developmental neuropsychological assessment. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Serra-Negra JM, Paiva SM, Seabra AP, Dorella C, Lemos BF, Pordeus IA. Prevalence of sleep bruxism in a group of Brazilian schoolchildren. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010;11:192–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03262743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Farsi NM. Symptoms and signs of temporomandibular disorders and oral parafunctions among Saudi children. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:1200–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2003.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fischer WF, O’toole ET. Personality characteristics of chronic bruxers. Behav Med. 1993;19:82–6. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1993.9937569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Manfredini D, Ciapparelli A, Dell’Osso L, Bosco M. Mood disorders in subjects with bruxing behavior. J Dent. 2005;33:485–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Stein MA, Mendelsohn J, Obermeyer WH, Amromin J, Benca R. Sleep and behavior problems in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E60. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Blumenshine SL, Vann WF, Jr, Gizlice Z, Lee JY. Children’s school performance: impact of general and oral health. J Public Health Dent. 2008;68:82–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hill CM, Hogan AM, Karmiloff-Smith A. To sleep, perchance to enrich learning? Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:637–43. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.096156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]