Abstract

The epidermal growth factor (EGF) activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt cascade among other signaling pathways. This route is involved in cell proliferation and survival, therefore, its dysregulation can promote cancer. Considering the relevance of the PI3K-Akt signaling in cell survival and in the pathogenesis of cancer, and that GH was reported to modulate EGFR expression and signaling, the objective of this study was to analyze the effects of increased GH levels on EGF-induced PI3K-Akt signaling. EGF-induced signaling was evaluated in the liver of GH overexpressing transgenic mice and in their normal siblings. While Akt expression was increased in GH-overeexpressing mice, EGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt, relative to its protein content, was diminished at Ser473 and inhibited at Thr308; consequently, mTOR, which is a substrate of Akt, was not activated by EGF. However, the activation of PDK1, a kinase involved in Akt phosphorylation at Thr308, was not reduced in transgenic mice. Kinetics studies of EGF-induced Akt phosphorylation showed that it is rapidly and transiently induced in GH-overexpressing mice compared with normal siblings. Thus, the expression and activity of phosphatases involved in the termination of the PI3K-Akt signaling were studied. In transgenic mice, neither PTEN nor PP2A were hyperactivated; however, EGF induced the rapid and transient association of SHP-2 to Gab1, which mediates association to EGFR and activation of PI3K. Rapid recruitment of SHP2, which would accelerate the termination of the proliferative signal induced, could be therefore contributing to the diminished EGF-induced activity of Akt in GH-overexpressing mice.

Keywords: Growth hormone (GH), Epidermal growth factor (EGF), PI3K-Akt pathway, GH transgenic mice, Grb2-associated binder-1 (Gab1)

1. Introduction

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signaling pathway is activated by many types of cellular stimuli and regulates fundamental cellular functions such as transcription, translation, proliferation, growth, and survival [1,2]. When PI3K is activated, it is able to convert phosphatidylinositol-4,5 bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) to PI(3,4,5)P3, whereas PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) reverses this reaction. Akt translocates to the cell membrane and interacts with PI(3,4,5)P3 via its PH domain. The interaction of the PH domain of Akt with PI(3,4,5)P3 provokes conformational changes in Akt, resulting in the exposure of its two main phosphorylation sites, Thr308 in the kinase domain and Ser473 in the C-terminal regulatory domain. The PH domain of Akt also mediates its interaction with PDK1, which phosphorylates Akt at Thr308, leading to stabilization of its active conformation. Although phosphorylation of Thr308 is a requirement for the activation of Akt, the concomitant phosphorylation at Ser473 leads to the full activation of this kinase [3,4,5]. Several studies have shown that phosphorylation at the two sites can occur independently [4,5]. Activated Akt modulates the function of numerous substrates involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, including glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors P21/Waf1/Cip1 and P27/Kip2, and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [6,7]. The dysregulation of this pathway has been associated with the development of diseases such as cancer, diabetes mellitus, and autoimmunity [2,4]. The development and progression of cancer are the results of uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival and the PI3K-Akt signaling controls both of these events, therefore its dysregulation plays a major role in tumor growth. Akt has been described to be constitutively active in many types of human cancer due to amplification or mutations in components of the signaling pathway that activate this kinase. In different types of cancer the PI3KCA gene, which encodes the p110a catalytic subunit of PI3K, is amplified [4]. Cell surface receptors are commonly overexpressed or constitutively active in many types of cancers and downstream signaling pathways, including the PI3K-Akt pathway, are often activated as a result. Moreover, the dysregulation of negative regulators of the PI3K-Akt pathway is related to cancer progression, and thus absence of PTEN strongly correlates with activation of Akt in tumor cell lines [8].

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is among the tyrosine kinase receptors that can activate the PI3K-Akt pathway. EGFR, also called ErbB-1, belongs to a family of receptors that comprises three additional proteins, ErbB-2, ErbB-3 and ErbB-4. ErbB receptors are activated by binding of growth factors of the EGF family which are produced in an autocrine or paracrine fashion. EGF binding to its receptor leads to the activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase domain and phosphorylation of multiple tyrosine residues within its intracellular domain [9,10]. This activation triggers intracellular signaling cascades such as the MAPKs, the PKC, the STAT and the PI3K-Akt pathways, involved in cell proliferation, survival and motility [11,12,13]. ErbB receptors have been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis and progression of different types of carcinoma [12,14,15]. EGFR undergoes different alterations including gene amplification, structural rearrangements, and somatic mutations in human carcinomas; moreover, some types of tumors produce an excess of EGF that leads to an increased activation of EGFR [13]. Besides anomalies in EGF receptor expression and ligand production, intracellular signaling pathways are often altered in cancer cells, including the PI3K-Akt pathway. All these alterations in EGF-mediated survival signaling pathways contribute to cancer progression and resistance to cancer therapies. In particular, amplifications or mutations of the efgr gene or overexpression of this receptor frequently occur in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [16,17].

EGFR phosphorylation is induced not only by direct binding of specific ligands but also by growth factors such as growth hormone (GH) and prolactin (PRL). GH was reported to induce the transphosphorylation of the EGFR at tyrosines 845, 992, 1068 and 1173 [18,19,20,21]. Another level of interaction between GH and EGF signaling involves GH-induced EGFR phosphorylation at threonine residues. Such phosphorylation reduces EGF-induced EGFR degradation, thus modulating EGFR trafficking and signaling [21]. In addition, EGFR expression has been demonstrated to be regulated by GH [22,23,24]. Partially GH-deficient mutant mice and hypophysectomized mice showed reduced expression of the EGFR in liver. When GH was administered to these mice, EGFR expression was induced approaching EGFR levels found in normal mice [23]. We have recently demonstrated that EGFR expression is diminished in GH receptor knock-out mice while it is increased in transgenic mice over expressing GH [24,25]. Moreover, crosstalk between GH and EGF signaling pathways comprising diverse signaling mediators has been described.

Growth hormone is a pituitary hormone involved in longitudinal growth promotion and metabolic processes. However, several studies have demonstrated that, in addition to its physiological effects, GH is involved in tumorigenesis and tumor progression. GH overexpression has been associated with cancer in animals as well as in humans; indeed, acromegalic patients show an increased incidence of this pathology [26,27,28,29]. On the contrary, a decreased incidence of cancer in the absence of GH or its receptors has been observed [30,31]. Transgenic mice overexpressing GH are more likely to develop cancer [32,33,34] and they have an increased tendency to develop liver tumors, including hepatocellular carcinoma, at advanced ages [34,35]; while GH resistance or deficiency are associated with reduced tendency to develop malignancies spontaneously [36,37] or in response to carcinogen administration [38,39]. The main GH-induced signaling pathway, JAK2-Stat5, is desensitized in transgenic mice overexpressing GH [40,41]. Nevertheless, these mice show increased expression and basal phosphorylation levels of EGFR and Akt [24,25]. Considering GH modulation of EGFR expression and activation, the relevance of the PI3K-Akt signaling in cell survival and in the pathogenesis of cancer, as well as the implication of GH and EGFR in the development of hepatocarcinoma, the objective of this study was to analyze the modulatory role of GH overexpression in EGF-induced PI3K-Akt signaling in mice liver.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Reagents

Highly purified ovine growth homone (oGH) of pituitary origin was obtained through the National Hormone and Pituitary Program, NIDDK, NIH, USA. Recombinant human EGF, Trizma base, HEPES, Tween 20, Triton X-100, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), glycine, ammonium persulphate, aprotinin, phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), sodium orthovanadate, 2-mercaptoethanol, molecular weight markers and BSA-fraction V were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Missouri, USA.). PVDF membranes, high performance chemiluminescence film and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL)-Plus are from Amersham Biosciences (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NY, USA). Mini Protean apparatus for SDS-polyacrylamide electrophoresis, miniature transfer apparatus, acrylamide, bis-acrylamide and TEMED were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, California, USA). Secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP and antibody anti-Gab1 (H-198) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Laboratories (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies anti-phospho-Gab1 Tyr627, anti-phospho-Akt Ser473, anti-phospho-Akt Thr308, anti-Akt, antiphospho-mTOR Ser2448, anti-mTOR, anti-PDK1, anti-PTEN, antiphospho-PDK1 Ser241, anti-phospho-PTEN Ser380 were from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit was obtained from Thermo Scientific, Pierce Protein Research Products (Rockford, IL, USA). PP2A Immunoprecipitation Phosphatase Assay Kit was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA).

2.2. Animals

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK)-bGH mice containing the bGH gene fused to control sequences of the rat Pepck gene [42] were derived from animals kindly provided by Drs T E Wagner and J S Yun (Ohio University, Athens, OH, USA). The hemizygous transgenic mice were derived from a founder male, and were produced by mating transgenic males with normal C57BL/6XC3H F1 hybrid females purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mating produced approximately equal proportions of transgenic and normal progeny. Normal siblings of transgenic mice were used as controls. Female and male adult animals (4–7 months old) were used. The mice were housed 3–5 per cage in a room with controlled light (12 h light/day) and temperature (22±2 °C). The animals had free access to food (Lab Diet Formula 5001 containing a minimum of 23% protein, 4.5% fat and a maximum of 6% crude fiber, from Purina Mills Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) and tap water. The appropriateness of the experimental procedure, the required number of animals used, and the method of acquisition were in compliance with federal and local laws, and with institutional regulations.

2.3. Animal treatments

PEPCK-bGH transgenic mice and their normal littermate controls were fasted for 6 h prior to i.p. injection with 2.5 mg oGH per kg of body weight (BW) or with recombinant human EGF at 2 mg/kg BW in 0.9% w/v NaCl. Mice were killed 7.5 minutes after GH injection or 10 minutes after EGF administration [24, 25], to study phosphorylation kinetics mice were killed 2.5, 5, 10 and 15 minutes after EGF stimulation. Additional mice were injected with saline to evaluate basal conditions. The livers were removed and stored frozen at −70 °C until homogenization.

2.4 Preparation of liver extracts

Liver samples were homogenized at the ratio 0.1g/1ml in buffer composed of 1% v/v Triton, 0.1 mol l−1 Hepes, 0.1 mol l−1 sodium pyrophosphate, 0.1 mol l−1 sodium fluoride, 0.01 mol l−1 EDTA, 0.01 mol l−1 sodium vanadate, 0.002 mol l−1 PMSF, and 0.035 trypsin inhibitory units/ml aprotinin (pH 7.4) at 4 C. Liver homogenates were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 40 min at 4 C to remove insoluble material. Protein concentration of supernatants was determined by the BCA protein assay kit. An aliquot of solubilized liver was diluted in Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min and stored at −20 C until electrophoresis.

2.5 Immunoprecipitation

Aliquots of solubilized liver containing 4 mg of protein were incubated at 4 C overnight with anti-Gab1 antibody. After incubation, 20 µl protein A-Sepharose (50% v/v) were added to the mixture. The preparation was further incubated with constant rocking for 2 h and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 1 min at 4 C. The precipitate was washed three times with washing buffer (0.05 mol l−1 Tris, 0.01 mol l−1 vanadate, and 1% v/v Triton X-100, pH 7.4). The final pellet was resuspended in 35 µl Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, and stored at −20 C until electrophoresis.

2.6 Immunoblot

Samples were subjected to electrophoresis in SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Electrotransference of proteins from gel to PVDF membranes and incubation with antibodies were performed as it was described by González et al. (2010). Immunoreactive proteins were revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence. Band intensities were quantified using Gel-Pro Analyzer 4.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA).

To reprobe with other antibodies, the membranes were washed with acetonitrile for 10 min and then incubated in stripping buffer (2% w/v SDS, 0.100 mol l−1 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.0625 mol l−1 Tris/HCl, pH 6.7) for 40 min at 50 C while shaking, washed with deionized water and blocked with BSA.

2.7 PP2A activity assay

PP2A was immunoprecipitated using 4 mg of solubilized liver protein. The phosphatase activity was subsequently measured according to PP2A Immunoprecipitation Phosphatase Assay Kit manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed analyzing all groups of animals in parallel, n representing the number of different individuals used in each group. Results are presented as mean ± SEM of the number of samples indicated. Statistical analyses were performed by ANOVA followed by the Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test using the GraphPad Prism 4 statistical program by GraphPad Software, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). Student’s t test was used when the values of two groups were analyzed. Data were considered significantly different if P < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

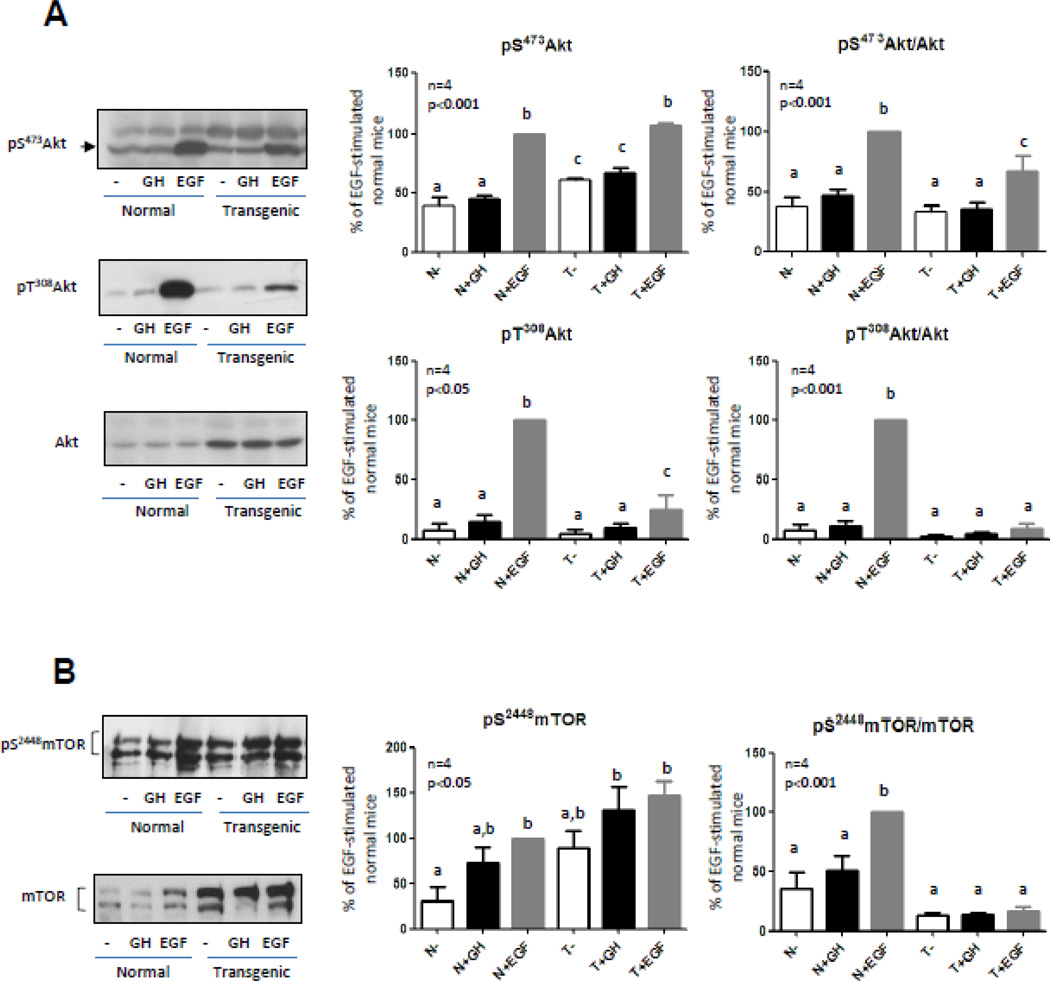

In order to study GH modulatory effects on hepatic Akt-mediated EGF signaling, protein content and activation of Akt were analyzed in solubilized liver from transgenic mice that overexpress GH and in their normal siblings. As previously reported, Akt content was increased in transgenic mice liver [24,25]. Nevertheless, EGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 was not different between normal and transgenic mice [24]. Results expressed as the relationship between phosphorylation and protein content of Akt demonstrated that, even while Akt phosphorylation was induced by EGF in the transgenic mice, Akt response to this growth factor was lower in these animals (Fig. 1A). EGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt Thr308 was reduced in the transgenic compared to normal mice. Moreover, when phosphorylation levels were related to the protein content, phosphorylation at this residue was found to be not significantly induced by GH or EGF in the liver of transgenic mice (Fig. 1A). GH-induced phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and Thr308 was studied in parallel to EGF-induction. In accordance with previous results, Akt was not activated by GH in the experimental conditions used, neither at Ser473 nor at Thr308.

Figure 1. Akt and mTOR content and phosphorylation in normal and GH-overexpressing mice.

Normal (N) and PEPCK-bGH transgenic mice (T) were injected i.p. with saline, GH (2.5 mg/kg BW), or EGF (2 mg/kg BW), killed after 7.5 or 10 min respectively, and the livers were removed. Equal amounts of solubilized liver protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Representative results of immunoblots with anti-Akt, anti-phospho-Akt S473, anti-phospho-Akt T308 (A), anti-mTOR and anti-phospho-mTOR S2448 (B) are shown. Quantification was performed by scanning densitometry and expressed as percent of values measured for EGF-stimulated normal mice. Data resulting from quantification analysis were used to calculate the pS473Akt/Akt, pT308 Akt/Akt and pS2448 mTOR/mTOR ratios. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of the indicated number of subsets (n) of different individuals. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA. Different letters denote significant difference at P<0.05.

Phosphorylation at residues Ser473 and Thr308 is critical to induce Akt activity. It is well established that the Ser/Thr kinase phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) governs phosphorylation of Thr308, while the enzyme that mediates phosphorylation at Ser473 remains controversial. This residue may be a substrate of mTOR [43], protein kinase C [44], DNA-protein kinase [45] or a putative PDK2 [46]. Regardless of the activating kinase, Akt phosphorylation on these two residues works synergistically; Akt activity is significantly attenuated when only one of these two sites is phosphorylated [5]. Considering the results described and the importance of phosphorylation at both sites to fully activate Akt, the activation status of one of the main Akt targets, mTOR, was determined.

Mammalian TOR is a Ser/Thr kinase of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–related kinase protein family and a central modulator of cell growth. mTOR plays a critical role in transducing growth and proliferative signals mediated through the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, principally by activating downstream protein kinases that are required for both ribosomal biosynthesis and translation of key mRNAs of proteins required for G(1) to S cell cycle phase traverse. Akt phosphorylates and activates mTOR, thus inducing protein synthesis and cell growth [4,47]. mTOR expression was studied by western blotting in normal and transgenic mice. The protein content and basal phosphorylation of mTOR were found to be increased in transgenic mice (Fig. 1B), as described previously [25]. Resembling the results obtained for Akt, mTOR phosphorylation was not induced by GH in normal or transgenic mice (Fig. 1B). Upon EGF stimulation, mTOR phosphorylation was induced in liver from normal and transgenic mice but, in transgenic mice, the increment was minor compared with EGF-induced phosphorylation of mTOR in normal mice (Fig 1B). In accordance with results obtained for Akt Thr 308, mTOR phosphorylation was found to be not significantly different from basal phosphorylation levels when data were related to the protein content (Fig 1B). Decreased EGF-induced phosphorylation of mTOR could be due to the reduction in Akt Thr308 phosphorylation observed in the transgenic mice upon EGF stimulation.

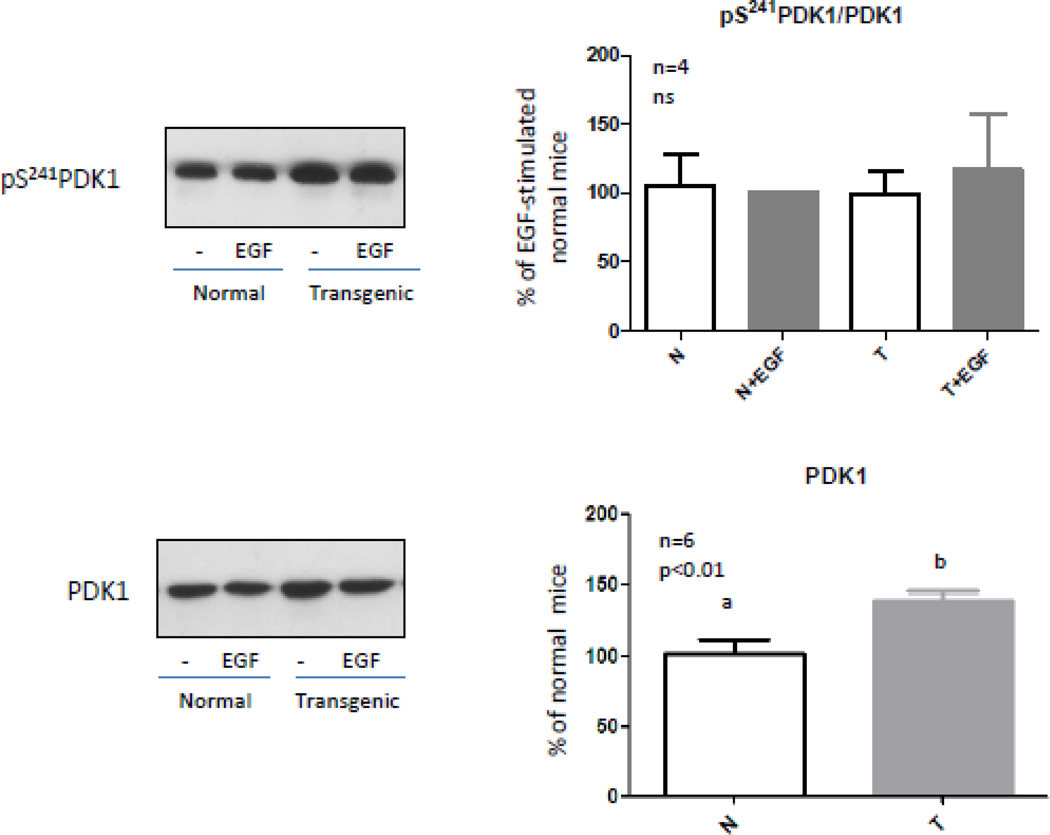

PDK1 phosphorylates Akt in the Thr308 residue. This kinase would be constitutively activated probably by autophosphorylation on Ser241 [48]. Considering that EGF is not able to induce Akt phosphorylation at residue Thr308 in the liver of transgenic mice, protein content and phosphorylation of this kinase were analyzed in normal and transgenic mice. Immunoblotting results showed that the protein content and basal phosphorylation levels of PDK1 were increased in transgenic mice (Fig. 2) and PDK1 phosphorylation was not induced by EGF neither in normal nor in transgenic mice (Fig 2). PDK1 would exist in an active, phosphorylated configuration under basal conditions and would be refractive to additional activation and phosphorylation upon cell stimulation with agonists which activate PI3K [48,49]. When phosphorylation levels of PDK1 were related to the protein content similar results were obtained for normal and transgenic mice (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the suppression of the Akt phosphorylation at Thr308 in EGF-stimulated transgenic mice is not due to reduced basal activity of PDK1.

Figure 2. PDK1 content and phosphorylation in normal and GH-overexpressing mice.

Normal (N) and PEPCK-bGH transgenic mice (T) were injected i.p. with saline or EGF (2 mg/kg BW), killed after 10 min and the livers were removed. Equal amounts of solubilized liver protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Representative results of immunoblots with anti-PDK1 and anti-phospho-PDK1 S241 are shown. Quantification was performed by scanning densitometry and expressed as percent of values measured for EGF-stimulated normal mice. Data resulting from quantification analysis were used to calculate the pS241PDK1/PDK1 ratio. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of the indicated number of subsets (n) of different individuals. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA or Student’s t test.

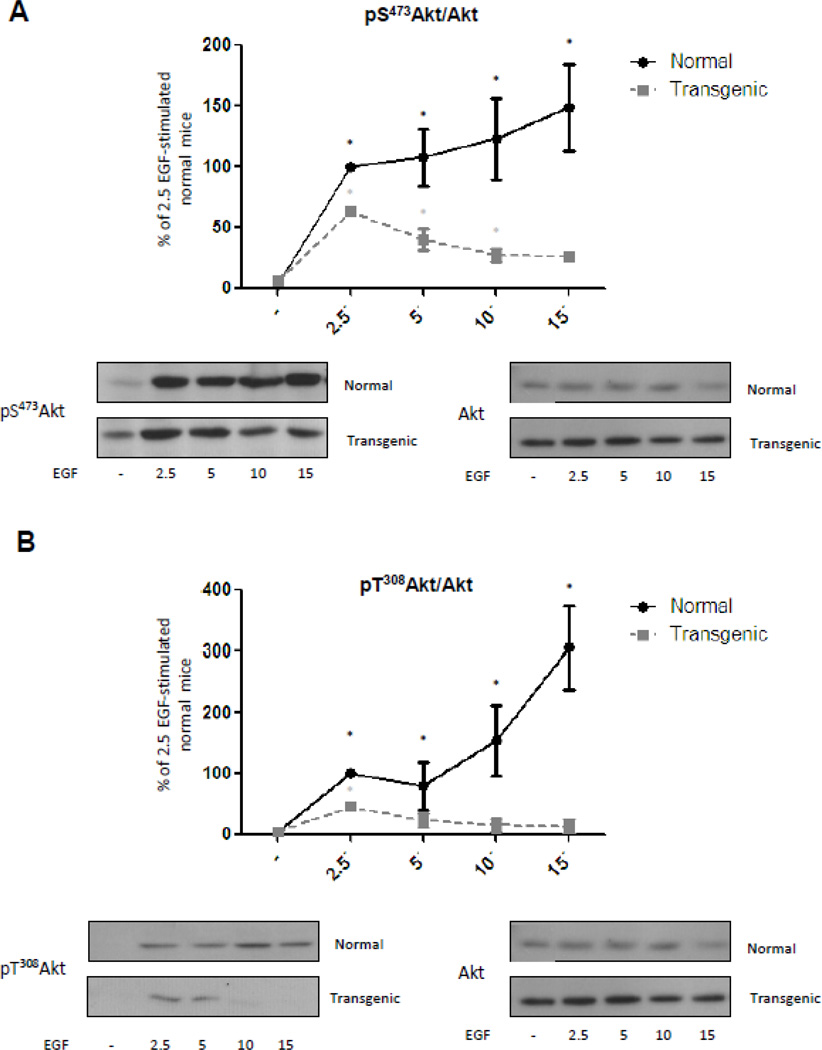

The results described in figure 1A for Akt phosphorylation were obtained after 10 minutes of EGF stimulation. This pattern of Akt phosphorylation could depend on an exacerbated activity of the mechanisms that terminate the signal instead of depending on a decreased activity of those that induce Akt phosphorylation at Thr308. To analyze this possibility, kinetic studies were performed. Normal and transgenic mice were stimulated with EGF during 2.5, 5, 10 or 15 minutes and liver extracts analyzed by western blotting. In normal mice there was a rapid and sustained phosphorylation of Akt Ser473 after stimulation with EGF (Fig. 3A). Transgenic mice also had a rapid response which was not sustained, as phosphorylation of Akt Ser473 rapidly decreased and 15 minutes after stimulation was no longer significantly different from basal values (Fig. 3A). Maximum increase of Akt phosphorylation at Ser 473 achieved in liver from transgenic mice occurred 2.5 min after EGF stimulation, but it was lower than the phosphorylation reached at the same time in liver from normal mice (Supplementary Figure A). For normal mice, Akt phosphorylation at Thr308 was significantly different from basal values 2.5 minutes after stimulation with EGF and it further increased thereafter (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, transgenic mice presented a rapid but transient response. In these animals, phosphorylation at Thr308 was significantly different from basal levels 2.5 minutes after EGF stimulation but was not sustained (Fig. 3B). Indeed, phosphorylation at the Thr308 residue 5 minutes after stimulation and later on did not significantly differ from basal phosphorylation levels. Thr308 Akt phosphorylation 2.5 min after EGF-stimulation was lower in transgenic mice compared to normal animals (Supplementary Figure B). Similarly to the results obtained for Ser473, maximum phosphorylation ratio for Thr308 was achieved at 2.5 min in the liver of GH-overexpressing mice this was much earlier and had lower intensity than the maximum phosphorylation ratio achieved in liver from the normal mice.

Figure 3. Kinetics of Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 and Thr308 related to protein content in normal and GH-overexpressing mice.

Normal (N) and PEPCK-bGH transgenic mice (T) were injected i.p. with saline or EGF (2 mg/kg BW), killed after 2.5, 5, 10 or 15 min and the livers were removed. Equal amounts of solubilized liver protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Quantification was performed by scanning densitometry and expressed as percent of values measured for EGF 2.5´ stimulated normal mice. Data resulting from quantification analysis were used to calculate the pS473Akt/Akt (A) and pT308Akt/Akt (B) ratio. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of the indicated number of subsets (n) of different individuals. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA. * denote significant difference at P<0.05 compared to non-stimulated mice.

The results of the kinetic studies showed that EGF induced Akt phosphorylation in normal mice and that this phosphorylation persisted in time for both residues, while transgenic mice presented a rapid and reduced response that promptly declined. Transient nature of the phosphorylation of Akt in the transgenic mice was more pronounced in the case of Thr308, indeed 5 minutes after EGF-administration phosphorylation levels were no longer significantly different from basal values. Results indicate that Akt can be activated in transgenic mice but mechanisms involved in the termination of the signal might be exacerbated. For this reason, mechanisms involved in Akt signaling termination after EGF stimulation were subsequently studied in the transgenic mice.

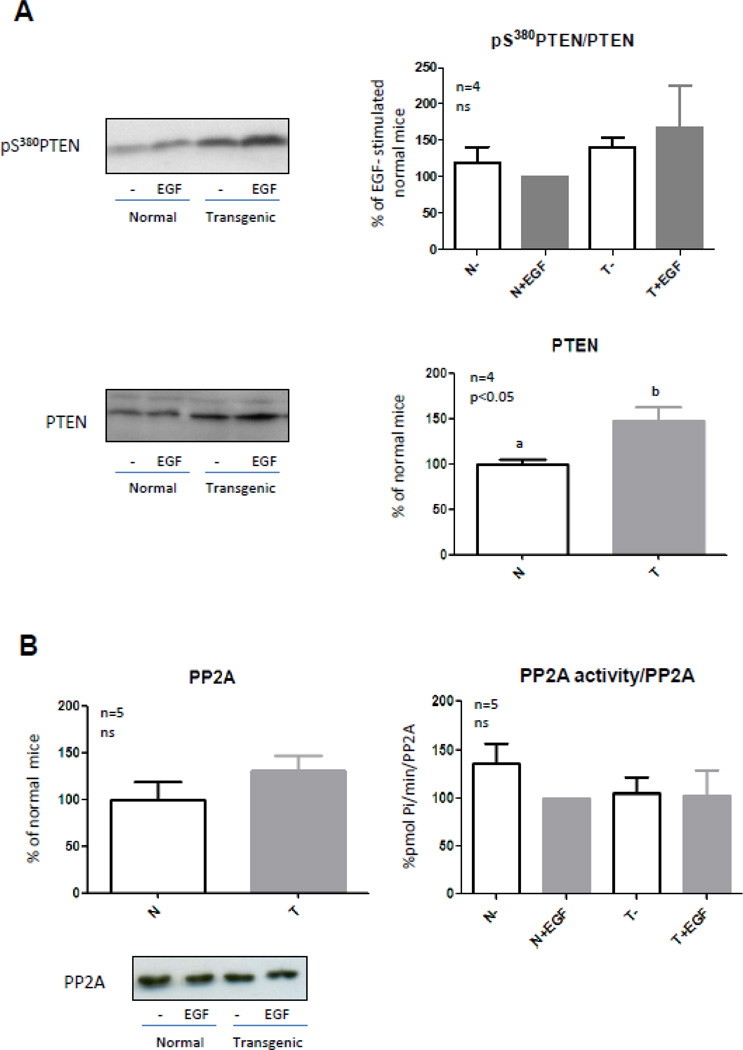

Negative regulation of the PI3K-Akt pathway is mainly accomplished by the phosphatase PTEN. PTEN is a major tumor suppressor gene which loss is associated with increased cell proliferation, reduced apoptosis and induction of tumor angiogenesis. It has been demonstrated that siRNA targeting liver endothelial cells PTEN result in efficient anti-tumoral effects [50]. Moreover, anti-tumoral action of gefitinib, the EGFR inhibitor, on HCC-induced angiogenesis would involve a PTEN/Akt signaling pathway [51].

The main lipid substrate of PTEN is PIP3, which is produced by PI3K when it is activated and mediates Akt translocation to the cell membrane and its subsequent activation. PTEN reduces the amount of PIP3 by dephosphorylation and changes it into PIP2 [3]. Therefore, Akt interaction with the plasma membrane and its following activation are diminished. Immunoblotting was performed to analyze PTEN protein content and its phosphorylation on Ser380. Phosphorylation at Ser380 restricts PTEN activity while dephosphorylation results in an increase in PTEN activity and its rapid degradation [52]. The protein level of PTEN was increased in transgenic mice (Fig. 4A) but phosphorylation of PTEN on Ser380 also showed an increase (Fig. 4A); therefore, increased PTEN content in liver from transgenic mice was not accompanied by an increase in its activation. PTEN phosphorylation was not induced by EGF in normal and transgenic mice. The relationship between the phosphorylation and the protein content of PTEN was similar between normal and transgenic mice (Fig. 4A). Taking into account that even if PTEN is increased in transgenic mice it is concomitantly inhibited, this protein overexpression would not be involved in the different kinetics of Akt phosphorylation observed in the transgenic mice.

Figure 4. PTEN content and phosphorylation, and PP2A activity in normal and GH-overexpressing mice.

Normal (N) and PEPCK-bGH transgenic mice (T) were injected i.p. with saline or EGF (2 mg/kg BW), killed after 10 min and the livers were removed. Equal amounts of solubilized liver protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis (A and B) or immunoprecipitated with anti-PP2A antibody in order to measure its activity (B). Representative results of immunoblots with anti-PTEN, anti-phospho-PTEN S380 (A) and anti-PP2A (B) are shown. Quantification was performed by scanning densitometry and expressed as percent of values measured for EGF-stimulated normal mice. Data resulting from quantification analysis were used to calculate the ratio pS380 PTEN/PTEN (A) and PP2A activity/PP2A content (B). Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of the indicated number of subsets (n) of different individuals. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA or Student’s t test.

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) comprises a family of serine/threonine phosphatases, containing a well conserved catalytic subunit, the activity of which is highly regulated. PP2A is involved in the regulation of cellular metabolism, DNA replication, transcription, cell-cycle progression, morphogenesis, development and transformation [57]. This phosphatase binds to Akt and preferentially dephosphorylates Thr308 [54], although it can also dephosphorylate Akt on Ser473 under certain conditions. PP2A basal and EGF-induced enzymatic activity and protein content were measured in the solubilized liver of normal and transgenic mice. For this purpose, PP2A was immunoprecipitated from solubilized liver of normal and transgenic mice and the enzymatic activity of the phosphatase was measured in vitro. No differences in basal or EGF-induced phosphatase activity or protein levels of PP2A were found between normal and transgenic mice (Fig 4B), suggesting that other mechanisms might be accelerating Akt dephosphorylation in the transgenic mice overexpressing GH.

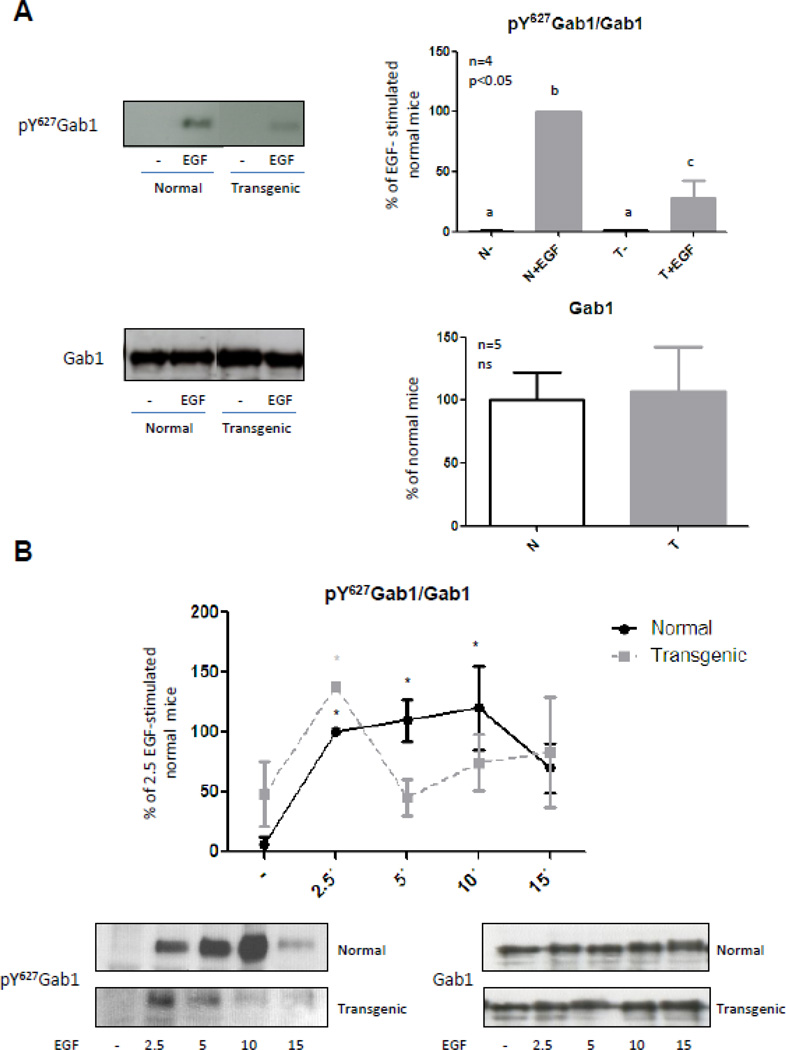

EGF stimulation of the PI3K-Akt pathway requires the docking protein Gab1 (Grb2-associated binder-1). After activation and phosphorylation of the EGFR, the adaptor protein Grb2 binds to the receptor and mediates Gab1 association to the EGFR via binding to a proline rich region on Gab1 [55,56]. Gab1 contains a number of tyrosine residues that can act as binding sites for p85, which is the catalytic subunit of PI3K, and the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP2. Gab1 thus functions as a docking protein facilitating the recruitment of several proteins including the EGFR, p85 and SHP2 in response to EGF treatment [57]. Previous results from our laboratory have demonstrated that SHP2 is increased in microsomal membranes from liver of transgenic mice overexpressing GH [41]. Moreover, we have recently established that the desensitization of STAT5-mediated signal described in the transgenic mice upon EGF stimulation could be due to the increased association of SHP2 and STAT5 in the GH-transgenic mice [24]. Althought the role of SHP2 in the control of EGFR-Gab1 interaction is not well understood, several studies have suggested that Gab1-associated SHP2 may influence EGF-induced PI3K signaling. SHP2 may specifically dephosphorylate the tyrosine phosphorylation sites on Gab1 that bind p85, thus preventing the recruitment of PI3K and EGF-induced activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway [58]. It has been shown that cells devoid of SHP2 show increased PI3K activity as well as elevated and sustained levels of Akt activation in response to EGF treatment [59]. Increased association of SHP2 to Gab1 in liver of transgenic mice could be responsible for the desphophorylation of the PI3K binding site in the adaptor protein and thus the decrease of the response and duration of the signal induced by EGF. In order to study this possibility, Gab1 content and phosphorylation were determined by Immunobloting. Gab1 expression was not significantly different between normal and transgenic mice. This protein has different residues that become phosphorylated among which are Tyr472 that allows the binding and activation of PI3K, and Tyr627, that permits the recruitment of SHP2. Gab1 phosphorylation at Tyr627 was analyzed and the results showed that EGF-induced phosphorylation of Gab1 after 10 minutes of stimulation was reduced in transgenic mice (Fig. 5A), resembling the phosphorylation pattern observed for Ser473 of Akt (Fig. 1A). When the kinetics of Gab1 phosphorylation after EGF stimulation was analyzed, it was observed that phosphorylation of Tyr627 was significantly induced by EGF after 2.5 minutes and reached a maximum at 10 minutes after stimulation in normal mice (Fig. 5B), while in transgenic mice, the phosphorylation of Gab1 was significantly induced by EGF after 2.5 minutes and then it diminished (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Figure C).

Figure 5. Gab1 phosphorylation at Tyr627 related to protein content in normal and GH-overexpressing mice.

Normal (N) and PEPCK-bGH transgenic mice (T) were injected i.p. with saline or EGF (2 mg/kg BW), killed after 2.5, 5, 10 or 15 min and the livers were removed. Equal amounts of solubilized liver protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Quantification was performed by scanning densitometry and expressed as percent of values measured for EGF-stimulated normal mice. Data resulting from quantification analysis were used to calculate the pY627 Gab1/Gab1 ratio. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of the indicated number of subsets (n) of different individuals. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA or Student’s t test. Different letters denote significant difference at P<0.05 (A). * denote significant difference at P<0.05 compared to non-stimulated mice (B).

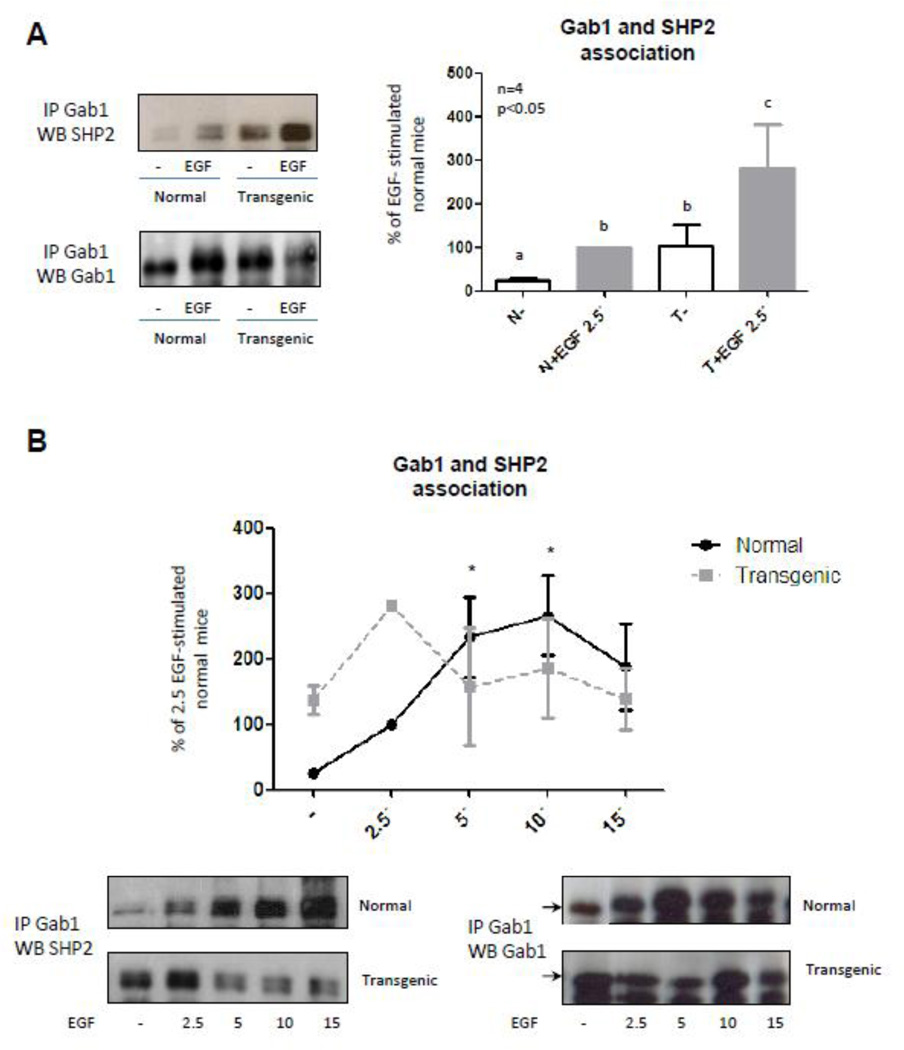

Results of the kinetic study of Gab1 phosphorylation at residue Tyr627 mimicked the kinetics of Akt activation described for normal and transgenic mice. These results suggest that, upon EGF stimulation, Gab1 phosphorylation at residue Tyr627 is rapidly induced in the liver of the transgenic mice leading to the recruitment of membrane-associated SHP2, which is increased in the transgenic mice [41]. Association of SHP2 to Gab1 could enable the rapid dephosphorylation of the tyrosine residue 472 in Gab1 and the subsequent termination of the signal mediated by PI3K and Akt. Therefore, coimmunoprecipitation assays were conducted to study the association between Gab1 and SHP-2 2.5 min after EGF stimulation. Results demonstrate that association between these proteins was higher in the liver of GH-overexpressing mice. Moreover transgenic mice showed an increase in Gab1-SHP-2 basal association. Subsequently, the kinetics of Gab1 and SHP2 association upon EGF-stimulation in normal and transgenic mice was assessed. In agreement with our expectations, results demonstrated that Gab1 and SHP2 association is rapidly induced in the transgenic mice while in normal mice it occurred later (Fig. 6). In conclusion, results demonstrate that basal association of SHP-2 to Gab1 was increased in GH-overexpressing mice. This could explain the generalized desensitization of the Akt pathway, while the rapid but short binding between SHP-2 and Gab1 upon EGF stimulation would explain the rapid and transient activation of Akt.

Figure 6. SHP2 coimmunoprecipitation with Gab1 in normal and GH-overexpressing mice.

Normal (N) and PEPCK-bGH transgenic mice (T) were injected i.p. with saline or EGF (2 mg/kg BW), killed after 2.5, 5, 10 or 15 min and the livers were removed. Equal amounts of solubilized liver protein were immunoprecipitated with anti-Gab1 antibody. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Quantification was performed by scanning densitometry and expressed as percent of values measured for EGF 2.5´ stimulated normal mice. Gab1 and SHP-2 association after 2.5 min EGF-stimulation was compared in normal and transgenic mice (A). Kinetic of EGF-induced association between Gab1 and SHP-2 was studied in normal and transgenic mice (B). Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of the indicated number of subsets (n) of different individuals. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA. * denote significant difference at P<0.05 compared to non-stimulated mice.

4. Conclusion

The effects of GH overexpression over EGF-induced PI3K-Akt signaling were analyzed in PEPCK-bGH transgenic in comparison to normal mice. The EGF-induced PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling was diminished in animals with chronically elevated GH levels. This desensitization was not due to a downregulation of the activation or expression of PDK1, kinase responsible for Akt phosphorylation at Thr308. Kinetic studies of Akt phosphorylation revealed that in normal mice it is induced and subsequently sustained during the period under study, while, in transgenic mice it is rapidly induced but declines thereafter. Results demonstrate that Akt was rapidly and transiently activated in the liver of transgenic mice but to a minor extent in control littermates. Neither PTEN nor PP2A are involved in the rapid termination of EGF-induced Akt signal. Instead, increased Gab1 basal recruitment of SHP-2 could account for the desensitization of the EGF-induced PI3K/Akt pathway in the transgenic mice liver, while rapid and transient recruitment of SHP-2 by Gab1 after EGF stimulus might explain kinetic phosphorylation of Akt in the liver of GH-overexpressing transgenic mice.

This study demonstrates that chronically elevated GH levels induce mechanisms that compensate the activation of EGF-induced proliferation signals mediated by PI3K-Akt. Such compensatory mechanism implies a rapid and transient recruitment and activation of SHP2 which accelerates the termination of the signal induced. This study suggests a protective role of SHP-2 in liver cells chronically exposed to increased GH levels.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The effects of increased GH levels on EGF-induced PI3K-Akt signaling were studied. GH overexpressing transgenic mice and their normal siblings were used. EGF-induced PI3K-Akt pathway is down-regulated by chronically elevated GH levels. Rapid and transient Gab1 recruitment of SHP2 would desensitize the PI3K-Akt pathway.

Acknowledgements

LG, JGM, AIS, and DT are Career Investigators of CONICET and MED and CSM are supported by a Fellowship from CONICET. Support for these studies was provided by UBA (B610), CONICET (PIP-427), and ANPCYT (PICT 749) to DT and LG, and by NIH via grants AG 19899 and AG031736 to AB. The Fulbright Commission and the CONICET awarded JGM a grant for a postdoctoral research stay at the Southern Illinois University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that would prejudice the impartiality of this scientific study.

Bibliography

- 1.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Genes Dev. 1999;13(22):2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2(7):489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osaki M, Oshimura M, Ito H. Apoptosis. 2004;9:667–676. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000045801.15585.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson KM, Anderson NG. Cell. Signal. 2002;14:381–395. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings BA. EMBO J. 1996;15(23):6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawlor MA, Alessi DR. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114(Pt 16):2903–2910. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sekulic A, Hudson CC, Homme JL, Yin P, Otterness DM, Karnitz LM, Abraham RT. Cancer Res. 2000;60(13):3504–3513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bangyan LS. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Bio.l. 2009;41(4):757–761. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boeri Erba E, Bergatto E, Cabodi S, Silengo L, Tarone G, Defilippi P, Jensen ON. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2005;4:1107–1121. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500070-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu SL, Kim J, Bandle RW, Liotta L, Petricoin E, Karger BL. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;9:1610–1627. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600105-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorissen RN, Walker F, Pouliot N, Garrett TP, Ward CW, Burgess AW. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;284:31–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Normanno N, De Luca A, Strizzi L, Mancino M, Maiello MR, Carotenuto A, De Feo G, Caponigro F, Salomon DS. Gene. 2006;366:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henson ES, Gibson SB. Cell. Signal. 2006;18:2089–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito Y, Takeda T, Sakon M, Tsujimoto M, Higashiyama S, Noda K, Miyoshi E, Monden M, Matsuura N. Br. J. Cancer. 2001;84(10):1377–1383. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Normanno N, Bianco C, De Luca A, Salomon DS. Front. Biosci. 2001;6:d685–d707. doi: 10.2741/normano. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Normanno N, Bianco C, Strizzi L, Mancino M, Maiello MR, De Luca A, Caponigro F, Salomon DS. Curr. Drug Targets. 2005;6(3):243–257. doi: 10.2174/1389450053765879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu XT, Zhu SN, Xu ZD, Hu XQ, Zhu TF, Chen JQ, Lu SL. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2007;133(3):145–152. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0139-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamauchi T, Ueki K, Tamemoto H, Sekine N, Wada M, Honjo M, Takahashi M, Takahashi T, Hirai H, Tushima T, Akanuma Y, Fujita T, Komuro I, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Nature. 1997;390:91–96. doi: 10.1038/36369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamauchi T, Ueki K, Tobe K, Tamemoto H, Sekine N, Wada M, Honjo M, Takahashi M, Takahashi T, Hirai H, Tushima T, Akanuma Y, Fujita T, Komuro I, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Endocr. J. 1998;45(Suppl):S27–S31. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.45.suppl_s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S, Houtman JCD, Jiang J, Ruppert JM, Bertics PJ, Frank SJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(50):36015–36024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.36015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Kim S, Jiang J, Frank SJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(21):18902–18913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansson JO, Ekberg S, Hoath SB, Beamer WG, Frohman LA. J. Clin. Invest. 1988;82:1871–1876. doi: 10.1172/JCI113804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansson S, Husman B, Norstedt G, Andersson G. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 1989;3:113–120. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0030113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.González L, Díaz ME, Miquet JG, Sotelo AI, Fernández D, Dominici FP, Bartke A, Turyn D. J. Endocrinol. 2010;204:299–309. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miquet JG, González L, Matos MN, Hansen C, Louis A, Bartke A, Turyn D, Sotelo AI. J. Endocrinol. 2008;198:317–330. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webb SM, Casanueva F, Wass JA. Pituitary. 2002;5(1):21–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1022149300972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins PJ. Horm. Res. 2004;62:108–115. doi: 10.1159/000080768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel G, Tomer Y. Endocr. Res. 2005;31(1):51–58. doi: 10.1080/07435800500229177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raccurt M, Lobie PE, Moudilou E, Garcia-Caballero T, Frappart L, Morel G, Mertani HC. J. Endocrinol. 2002;175:307–318. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1750307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brooks AJ, Waters MJ. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2010;6:515–525. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guevara-Aguirre J, Balasubramanian P, Guevara-Aguirre M, Wei M, Madia F, Cheng CW, Hwang D, Martin-Montalvo A, Saavedra J, Ingles S, de Cabo R, Cohen P, Longo VD. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3(70):70ra13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orian JM, Tamakoshi K, Mackay IR, Brandon MR. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990;82:393–398. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.5.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wanke R, Hermanns W, Folger S, Wolf E, Brem G. Pediatr. Nephrol. 1991;5:513–521. doi: 10.1007/BF01453693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snibson KJ. Tissue Cell. 2002;34:88–97. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartke A. Neuroendocrinology. 2003;78:210–216. doi: 10.1159/000073704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anisimov VN. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1221–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeno Y, Bronson RT, Hubbard GB, Lee S, Bartke A. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003;58:291–296. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.4.b291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Styles JA, Kelly MD, Pritchard NR, Foster JR. Carcinogenesis. 1990;3:387–391. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pollak M, Blouin MJ, Zhang JC, Kopchick JJ. Br. J. Cancer. 2001;85:428–430. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.González L, Miquet JG, Sotelo AI, Bartke A, Turyn D. Endocrinology. 2002;143:386–394. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miquet J, Sotelo AI, Bartke A, Turyn D. Endocrinology. 2004;145(6):2824–2832. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGrane MM, Yun JS, Moorman AF, Lamers WH, Hendrick GK, Arafah BM, Park EA, Wagner TE, Hanson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:22371–22379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, Soto N, Wei S, Jung SY, Huang Q, Qin J, Su B. Cell. 2006;127(1):125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawakami Y, Nishimoto H, Kitaura J, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Kato RM, Littman DR, Leitges M, Rawlings DJ, Kawakami T. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(46):47720–47725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng J, Park J, Cron P, Hess D, Hemmings BA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(39):41189–41196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shay KP, Hagen TM. Biogerontology. 2009;10(4):443–456. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:3589–3594. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casamayor A, Morrice NA, Alessi DR. Biochem. J. 1999;342:287–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vanhaesebroeck B, Alessi DR. Biochem J. 2000;346(Pt 3):561–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santel A, Aleku M, Keil O, Endruschat J, Esche V, Durieux B, Löffler K, Fechtner M, Röhl T, Fisch G, Dames S, Arnold W, Giese K, Klippel A, Kaufmann J. Gene Therapy. 2006;13:1360–1370. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao LQ, Chen XL, Wang Q, Huang XH, Zhen MC, Zhang LJ, Li W, Bi J. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28(6):879–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vazquez F, Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Sellers WR. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(14):5010–5018. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5010-5018.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janssens V, Goris J. Biochem. J. 2001;353(Pt 3):417–439. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuo YC, Huang KY, Yang CH, Yang YS, Lee WY, Chiang CW. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283(4):1882–1892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lock LS, Royal I, Naujokas MA, Park M. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(40):31536–31545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mattoon DR, Lamothe B, Lax I, Schlessinger J. BMC Biology. 2004;18:2–24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodrigues GA, Falasca M, Zhang Z, Ong SH, Schlessinger J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20(4):1448–1459. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1448-1459.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cunnick JM, Mei L, Doupnik CA, Wu J. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(26):24380–24387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang SQ, Tsiaras WG, Araki T, Wen G, Minichiello L, Klein R, Neel BG. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22(12):4062–4072. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4062-4072.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.