Abstract

Hypothesis

Increased cell motility is a hallmark of cancer cells. Proteins involved in cell motility may be used as molecular markers to characterize the malignant potential of tumors.

Methods

Molecular biology and immunohistochemistry techniques were used to investigate the expression of a selected panel of motility-related proteins (Rho A, Rac 2, Cdc42, PI(3)K, 2E4, and Arp2) in normal, premalignant, and squamous cell cancer cell lines of human head and neck origin. To assess the clinical potential of these proteins as molecular markers for cancer, immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-fixed head and neck cancer specimens (n = 15).

Results

All six motility-associated proteins were overexpressed in the premalignant and squamous cell cancer cell lines relative to normal keratinocytes. Immunohistochemistry with Rho A and Rac 2 showed increased staining in areas of cancer but not in normal tissue.

Conclusion

Proteins involved in cell motility can be used as markers for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The head and neck cell lines used in this study may be used as a model to further investigate cell motility. Molecular markers of motility could have a significant impact on the diagnosis and staging of cancers originating from differentiated non-motile cells.

Keywords: Cell motility, molecular markers, human cell lines, head and neck squamous cell cancer

INTRODUCTION

Invasion of adjacent normal tissue and metastasis are pathological criteria central to the diagnosis of malignant tumors. Metastasis is a multiple-step process that includes disruption of adhesion to neighboring cells and the extracellular matrix, adhesion to and transgression of endothelial cell barriers to gain entry and exit from the circulation, evasion of host defenses, and implantation and establishment of tumor at distant sites.1 Increased cell motility, manifested by the formation of membrane protrusions known as filopodia, lamellipodia, and pseudopodia, is a key cellular attribute which facilitates tumor invasion and metastasis.1–3 Reorganization of actin, an abundant cytoskeletal protein found in virtually all eukaryotic cells, is, in turn, necessary for cell motility.

Small guanosine 5'-triphosphate (GTP)-binding proteins such as Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 are responsible for triggering actin reorganization. Rho induces the assembly of contractile actin-based microfilaments such as stress fibers,4 Rac regulates the formation of lamellipodia and membrane ruffles,5 and Cdc42 activation is necessary for the formation of filopodia.6,7 These proteins are members of the Ras-related oncogene super-family and are known to have transforming capability, substantiating the role of cell motility in oncogenesis. They are in turn regulated by growth factors and other proteins with known oncogenic potential (Ost, Dbl, Vav, Ect2, Tiam-1).8

Activation of either Rac or Cdc42 is thought to activate phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI[3]K) and other enzymes (phospholipase D, phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase) which regulate formation of phospholipid messengers (Fig. 1). Direct activation of PI(3)K has been shown to cause cells to switch to a more motile, invasive phenotype.9

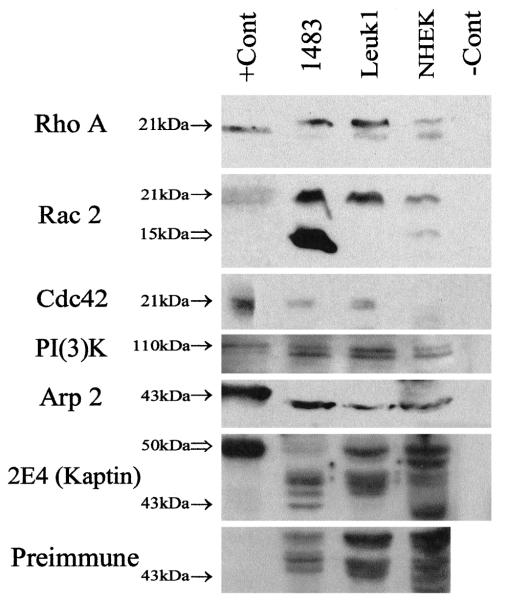

Fig. 1.

Proposed simplified cascade of molecular events necessary for cell motility and tumor cell metastasis. Unknown intermediary signaling molecules may be necessary.

Actin polymers (F-actin) consist of staggered, parallel rows of monomers (G-actin) non-covalently bound and twisted into a helix. The formation of actin filaments at the leading edge of the cell membrane is thought to propel cell locomotion.3 Initiation of actin polymerization requires the presence of actin oligomers (dimers and trimers of G-actin) to act as nucleation sites. The novel protein 2E4 (kaptin) has been shown to nucleate actin filaments from actin monomers in vitro, and is found at the leading edge of moving cells and at other sites of actin polymerization.3,10,11 Similarly, a complex of proteins, including actin-related protein 2 (Arp2), is known to initiate the formation and cross-linking of actin filaments.12,13

Disorder of the actin microfilament architecture characteristic of motile cells has been associated with a higher metastatic potential in tumors, including murine melanoma, fibrosarcoma, and adrenal carcinoma,14,15 and human thyroid, salivary, colon, lung, breast and prostate cancer and melanoma.1–3,16–21 Although tumor cell motility is recognized as an important contributor to the multistep metastatic process, relatively little investigation has been carried out regarding its importance as a prognostic factor.18–21 We propose that differential expression and staining of the motility-related proteins Rac 2, Rho A, Cdc42, PI(3)K, 2E4, and Arp2 may have significant diagnostic and prognostic value in the management of human cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

Norman human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK) were purchased from BioWhittaker (Walkersville, MD) and were cultured as instructed by the supplier. The premalignant MSK Leuk1 cell line was established from a dysplastic leukoplakia lesion adjacent to a squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in a 46-year-old nonsmoking female patient.22 The malignant 1483 cell line, derived from a T2N1M0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma of the retromolar trigone, has been described previously.23 Leuk1 cells are routinely maintained in serum-free keratinocyte growth medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD), while the 1483 cells are maintained in DMEM/F12 50:50 mix (Mediatech, Washington, DC) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and passaged using 0.125% trypsin-2 mmol/L EDTA. To control for differences in protein expression during the growth phase, cells were allowed to grow to confluence and then fed for an additional 2 to 3 days to establish mature, stable cell populations prior to final harvesting.

Antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies specific for Rho A, Rac 2, Cdc42, and PI(3)K (p110a subunit) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Recombinant bacterially expressed 2E4 and Arp 2 were purified by nickel column chromatography followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and submitted to Babco (Berkeley, CA) to generate rabbit polyclonal antibodies.

Western Blots

For all three cell lines, an equal cell number/volume whole cell lysate was prepared by trypsinizing and counting cells, and then boiling for 4 minutes in an appropriate volume of Laemilli gel sample buffer, according to established techniques.24 Positive control whole cell lysates for Rac 2 (HL-60), Rho A and Cdc42 (HeLa), and PI(3)K (COLO 320 DM) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Purified recombinant bacterially expressed 2E4 and Arp 2 positive controls were supplied by Dr. Elaine Bearer. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using standard immunoblotting procedures as described by Towbin et al.25 Blots were blocked in 5% milk solution, probed for 1 hour with the appropriate primary antibody, and detected on Kodak (Rochester, NY) X-omat film after incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit (#A6154, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or antigoat antibodies (Santa Cruz) and SuperSignal[regs] chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL), as instructed by the supplier.

Immunohistochemistry

Mature cells from each cell line were scraped, collected in phosphate-buffered saline, and formed into a compact cell block, per the protocol developed by Yang et al.,26 prior to routine fixation in formaldehyde and paraffin. Routinely fixed moderately and poorly differentiated head and neck squamous cell cancer surgical specimens from January 1998 through April 2000 were randomly selected (n " 15) from the surgical pathology files at Bellevue Hospital (New York, NY). Five-micrometer sections of the paraffin-embedded tissue were baked at 60°C for 30 minutes, deparaffinized in xylene, followed by rehydration in a graded ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving in 10 mmol/L citric acid for 20 minutes. Staining was performed on a Nexus automated immunohistochemistry instrument (Ventana, Tucson, AZ) with reagents supplied by the manufacturer. Briefly, endogenous peroxidase activity is blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide, primary antibody is added and detected using bio-tinylated antirabbit or antigoat secondary antibodies. Streptavidin–horseradish–peroxidase conjugate is added, and the complex visualized by the enzymatic reduction of 3,3' diamino-benzidine tetrahydrochloride substrate, enhanced with copper sulfate. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series followed by xylene, and mounted for viewing.

RESULTS

Western Blots

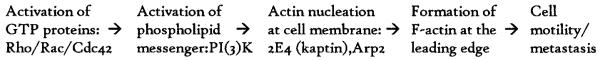

All of the Western blots showed increased expression of the motility proteins in the 1483 malignant squamous cell cancer cell line and the Leuk1 premalignant dysplastic cell line with respect to the NHEK normal human epidermal keratinocytes (Fig. 2, solid arrows, Rho A—21 kd, Rac 2—21 kd, Cdc42—21 kd, PI(3)K—110 kd, Arp 2—43 kd, 2E4—43 kd). Of note, on the Rac 2 blot (Fig. 2), there is a second strongly positive band at a lower molecular weight (open arrow, 15 kd) than the expected weight of Rac 2 (solid arrow, 21 kd), which is present primarily in the 1483 malignant squamous cell cancer cell line. This band may represent a breakdown product of Rac 2 recognized by this antibody and is addressed further in the Discussion. The bacterially expressed recombinant 2E4 protein runs at a higher molecular weight (Fig. 2, open arrow, 50 D) than the native protein (43 kd) in the positive control lane. Therefore, a parallel blot was performed with rabbit preimmune serum to confirm that the band at the expected molecular weight of native 2E4 (43 kd) is specific for the 2E4 protein. As is evident, the 43 kd 2E4 band (solid arrow) is present only in the 1483 cancer cell line on the 2E4 blot and is absent on the Preimmune blot (solid arrow). The Rho A and Rac 2 Western blots had few nonspecific bands, and therefore immunohistochemistry results are reported using these two antibodies.

Fig. 2.

Rho A, Rac 2, Cdc42, and Arp 2 Western blots of whole cell lysates separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, and PI(3)K, 2E4 (kaptin), and rabbit Preimmune Western blots separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Bands are present at the expected molecular weight of each protein (solid arrows: Rho A—21 kDA, Rac 2—21 kDa, Cdc42—21 kDa, PI(3)K—110 kDa, Arp 2—43 kDa, and 2E4—43 kDa). These bands are present in the positive control lane (except for 2E4, see explanation below), absent in the negative control lane, and increased in intensity in the malignant 1483 squamous cell cancer and premalignant Leuk1 dysplastic lanes relative to the normal NHEK keratinocytes lane on each blot, respectively. On the Rac 2 blot, there is a second intensely positive band (open arrow) at 15 kDa in the malignant 1483 lane, which appears to be absent or at a much lower concentration in the premalignant Leuk1 and normal NHEK lanes. This band may represent a breakdown product of Rac 2 and is addressed further in the Discussion. On the 2E4 blot, a band is present at 50 kDa in the positive control lane, the expected molecular weight of the recombinant bacterially expressed 2E4 protein (open arrow). As expected, this band is present in the malignant 1483 lane at 43 kDa, the expected molecular weight of native 2E4 (solid arrow). This band is absent in the negative control lane, premalignant Leuk1 lane, and normal NHEK lane on the 2E4 blot, and is absent in all lanes on the Preimmune blot (there is some overlap of nonspecific bands in the NHEK lane). Rho A +Cont = HeLa whole cell lysate; Rac 2 +Cont = HL-60 whole cell lysate; Cdc42 +Cont = HeLa whole cell lysate; PI(3)K +Cont = COLO 320 DM whole cell lysate; Arp 2 +Cont = purified recombinant bacterially expressed Arp 2; 2E4 +Cont = purified recombinant bacterially expressed 2E4; 1483 = malignant squamous cell cancer cell line; Leuk1 = premalignant dysplastic cell line; NHEK = normal human epidermal keratinocytes; −Cont = malignant squamous cell cancer (1483) whole cell lysate without secondary antibody.

Immunohistochemistry

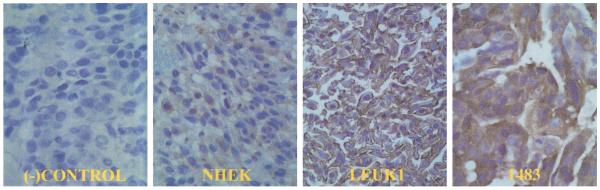

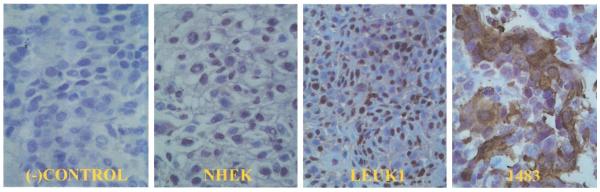

Compact cell block immunohistochemistry of the cell lines with Rho A and Rac 2 reveals specific differential staining patterns. Cytoplasmic staining of Rho A and nuclear staining of Rac 2 is sequentially increased in the NHEK normal human epidermal keratinocytes, the Leuk1 premalignant dysplastic cell line, and the 1483 malignant squamous cell cancer cell line, respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). In addition, with Rac 2, there is specific cytoplasmic staining of the 1483 cancer cell line which is absent in the normal NHEK and premalignant Leuk1 cell lines (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Compact cell block immunohistochemistry of cell lines with Rho A. Rho A is a cytoplasmic protein. As expected, there is no Rho A staining in the negative control panel. The expression of Rho A is sequentially increased in the premalignant Leuk1 and malignant 1483 cell lines relative to the normal NHEK cell line. (−)Control = 1483 cell line without primary antibody; NHEK = normal human epidermal keratinocytes; Leuk1 = premalignant dysplastic cell line; 1483 = malignant squamous cell cancer cell line (40× magnification).

Fig. 4.

Compact cell block immunohistochemistry of cell lines with Rac 2. As expected, there is no Rac 2 staining in the negative control panel. Rac 2 is a cytoplasmic protein. Cytoplastic staining of Rac 2 is present only in a subset of malignant 1483 cells. Sequentially increased nuclear staining is evident in the premalignant Leuk1 and malignant 1483 cell lines relative to the normal NHEK cell line. Refer to discussion for explanation. (−)Control = 1483 cell line without primary antibody; NHEK = normal human epidermal keratinocytes; Leuk1 = premalignant dysplastic cell line; 1483 = malignant squamous cell cancer cell line (40× magnification).

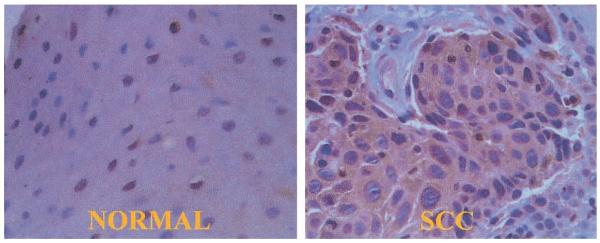

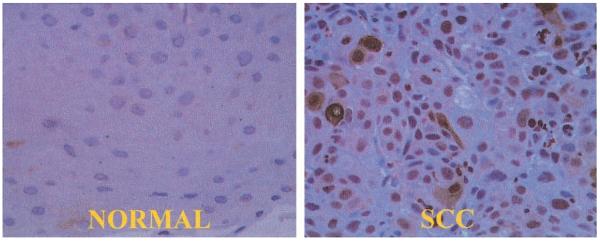

Rho A and Rac 2 immunohistochemistry of 15 moderately to poorly differentiated head and neck squamous cell cancer clinical pathology specimens demonstrated results identical to that observed with the cell lines (Figs. 5 and 6). There is specific increased expression of the Rho A and Rac 2 proteins in areas of squamous cell cancer compared with adjacent normal areas. As with the cell lines, there is specific cytoplasmic staining of a subset of cancer cells with Rac 2 which is not present in adjacent normal cells (Fig. 6). As an internal control, it was noted that normally motile cells found in sections of the specimen (macrophages) stained positive for Rho A and Rac 2, whereas constitutively non-motile cells (endothelium) did not.

Fig. 5.

Rho A immunohistochemistry of a moderately differentiated squamous cell cancer of the tongue surgical specimen. In the normal panel, it is evident that there is minimal staining of the normal tissue adjacent to the cancer. The nest of squamous cell cancer (SCC) cells is clearly stained by the Rho A antibody in the SCC panel. Rho A is a cytoplasmic protein (40× magnification).

Fig. 6.

Rac 2 immunohistochemistry of a moderately differentiated squamous cell cancer of the tongue surgical specimen. In the normal panel, there is minimal staining of the normal tissue adjacent to the cancer. In the SCC (squamous cell cancer) panel, there is both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining of squamous cell cancer cells. Note that not all cancer cells express cytoplasmic Rac 2. Refer to Discussion for explanation (40× magnification).

DISCUSSION

Our study reveals that motility-related proteins are clearly overexpressed in squamous cell cancer and dysplastic cell lines, relative to normal human keratinocytes, confirming the role of cell motility during malignant transformation of squamous cell cancer. Immunohistochemistry of head and neck cancer surgical specimens with Rho A and Rac 2 has shown that these two motility-associated proteins are excellent molecular markers of squamous cell cancer (Figs. 3–6). Differential cytoplasmic staining with Rac 2, in particular, may be able to distinguish frankly invasive squamous cell carcinoma-, from dysplastic lesions and benign normal mucosa (Figs. 4 and 6—cytoplasmic staining absent in the normal NHEK and premalignant Leuk1 cells, strongly positive in a subset of 1483 cancer cells). The graded nuclear staining seen with Rac 2 (minimal or absent in the NHEK normal cells, present in the Leuk1 premalignant, and the 1483 cancer cells) has not been reported previously. This nuclear staining, in addition to the intense second band at 15 kd in the 1483 cancer cell line found on the Rac 2 Western blot (Fig. 1—Rac 2, open arrow), indicates a possible endogenous Rac 2 breakdown product and merits further investigation.

The polyclonal antibodies to the other motility proteins investigated in our study (Cdc42, PI(3)K, 2E4, and Arp 2) show specific overexpression of these proteins on the Western blots in the 1483 malignant cancer cell line at the appropriate molecular weights (Fig. 1, Cdc42—21 kd, PI(3)K—110 kd, Arp 2—43 kd, 2E4—43 kd), but also recognize other nonspecific bands. However, immunohistochemistry using these antibodies did show differential staining of cancer cells (data not shown). These motility-related proteins, in addition to Rho A and Rac 2, could also potentially be used as molecular markers for squamous cell cancer.

There are a number of potential clinical applications for motility-related proteins. Because squamous cancer cells specifically overexpress proteins associated with motility such as Rho A and Rac 2, these proteins can be used to establish molecular margins in pathology specimens to increase the sensitivity of detecting occult disease missed by conventional histopathology techniques. Brennan et al. have reported using p53 mutations to determine molecular margins in head and neck cancers.27 In their study, 13 of 25 patients with negative surgical margins by conventional pathology were found to have positive margins using a polymerase chain reaction assay to detect p53 mutations. Five of these patients (39%) went on to develop recurrent disease, compared with none of the 12 patients who had negative molecular margins. However, only a subset of head and neck cancers has p53 mutations, limiting its clinical application. Because motility is an essential process in metastasis, proteins associated with motility are expected to be overexpressed in all cancers and may have more widespread use as molecular markers in detecting disease.

Proteins involved in cell motility may also be used to enhance clinical staging and as prognostic markers. Theoretically, cancers that overexpress motility-related proteins are more likely to metastasize and may require more radical locoregional or systemic therapy. Differential staining patterns of motility proteins such as cytoplasmic staining of Rac 2 (present only in the 1483 squamous cell cancer cells and not in the dysplastic Leuk1 cells; Fig. 4) could indicate more aggressive disease. This hypothesis needs to be validated by correlating motility-related protein expression with pathological and clinical prognostic and outcome parameters such as mitotic index, degree of differentiation, lymph node metastasis, and locoregional control. Immunohistochemistry with the motility-related proteins can be performed easily on standard paraffin-fixed pathology specimens, facilitating study of both fresh and archived tissue.

Many of the conventional chemotherapeutic agents currently used target cell division through cytoskeletal proteins (microtubules, actin filaments) and may indirectly affect cell motility.28 Once the mechanisms of cell motility are further elucidated, it may be possible to deliver more specific chemotherapy targeted to motility proteins. However, because cells of the immune system and cells in normal tissue undergoing healing or repair are also motile, it will be necessary to use techniques of localized drug delivery to minimize potential systemic side effects.

Finally, the head and neck cell lines used in this study provide a novel model to examine the molecular basis of cell motility. The spectrum of normal, dysplastic, and malignant cell lines may provide evidence of the sequence of molecular events during malignant transformation and could provide insight into the motility process in general.

CONCLUSION

Rho A, Rac 2, and other proteins involved in initiating cell motility are promising clinical molecular markers for head and neck squamous cell cancer. Additional studies are needed and are underway to determine the specific role these ubiquitous molecular markers could play in diagnosing, staging, and treating human cancers of nonmotile tissue. The normal, dysplastic, and squamous cell cancer cell lines described in this study provide relevant models to further investigate the molecular basis of cell motility.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Noel L. Cohen, MD, Susan Waltzman, PhD, Fang-An Chen, MD, PhD, Juan Mo, Rachael Gagne, Zhi Li, and Renato J. Giacchi, MD, for their technical assistance and support. This work was supported by the George E. Hall Endowment Grant.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Liotta L. Mechanisms of cancer invasion and metastasis. In: DeVita VT, Hellman A, Rosenberg S, editors. Progress in Oncology. vol 1. Lippincott; New York: 1985. pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham CC. Actin structural proteins in cell motility. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1992;11:69–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00047604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bearer EL. Role of actin polymerization in cell locomotion: molecules and models. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;8:582–591. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.6.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridley AJ. The small GTP-binding rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell. 1992;70:389–399. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein Rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell. 1992;70:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozma R, Ahmed S, Best A, Lim L. The Ras-related protein Cdc42Hs and bradykinin promote formation of peripheral actin microspikes and filopodia in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1942–1952. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, Rac, and CDC42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia. and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boivin D, Bilodeau D, Beliveau R. Regulation of cytoskeletal functions by Rho small GTP-binding proteins in normal and cancer cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:801–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keely PJ, Westwick JK, Whitehead IP, Der CJ, Parise LV. Cdc42 and Rac1 induce integrin-mediated cell motility and invasiveness through PI(3)K. Nature. 1997;390:532–536. doi: 10.1038/37656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bearer EL, Abraham MT. 2E4 (Kaptin). A novel actin-associated protein from human blood platelets found in lamellipodia and the tips of the stereocilia of the inner ear. Eur J Cell Biol. 1999;78:117–126. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bearer EL. An actin-associated protein present in the microtubule organizing center and the growth cones of PC-12 cells. J Neurosci. 1992;12:750–761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-00750.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manchesky LM, Gould KL. The Arp2/3 complex: a multifunctional actin organizer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welch MD. The world according to Arp: regulation of actin nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. Trends in Cell Biology. 1999;9:423–427. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raz A, Geiger B. Altered organization of cell-substrate contacts and membrane-associated cytoskeleton in tumor cell variants exhibiting different metastatic capabilities. Cancer Res. 1982;42:5183–5190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pokorna E, Jordan PW, O'Neill CH, Zicha D, Gilbert CS, Vesely P. Actin cytoskeleton and motility in rat sarcoma cell populations with different metastatic potential. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1994;28:25–33. doi: 10.1002/cm.970280103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demeure MJ, Hughes-Fulford M, Goretzki PE, Duh QY, Clark OH. Actin architecture of cultured human thyroid cancer cells: predictor of differentiation? Surgery. 1990;108:986–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman E, Verderame M, Winawer S, Pollack R. Actin cytoskeletal organization loss in the benign-to-malignant tumor transition in cultured human colonic epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1984;44:3040–3050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shieh DB, Godleski J, Herndon JE, II, et al. Cell motility as a prognostic factor in stage I nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: the role of gelsolin expression. Cancer. 1999;85:47–57. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990101)85:1<47::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao L, Loda M, Janmey PA, Stewart R, Anand-Apte B, Zetter BR. Thymosin beta15: a novel regulator of tumor cell motility upregulated in metastatic prostate cancer. Nat Med. 1996;2:1322–1328. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda K, Yamada T, Endo R, et al. Actinin-4, a novel actin-bundling protein associated with cell motility and cancer invasion. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1383–1393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slagia R, Li JL, Ewaniuk DS, et al. Expression of the focal adhesion protein paxillin in lung cancer and its relation to cell motility. Oncogene. 1999;18:67–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacks PG. Cell, tissue and organ culture as in vitro models to study the biology of squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1992;11:31–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00049486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacks PG, Parnes SM, Gallick GE, et al. Establishment and characterization of two new squamous cell carcinoma cell lines derived from tumors of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 1988;48:2858–2866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Towbin H, Staehlin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: a procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang GCH, Wan LS, Papellas J, Waisman J. Compact cell blocks. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:703–706. doi: 10.1159/000331830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban RH. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429–435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502163320704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordan MJ, Wilson L. Microtubules and actin filaments: dynamic targets for cancer chemotherapy. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]