Abstract

Very few studies have examined predictors of suicidal ideation among African American women. Consequently, we have a poor understanding of the combinations of culturally-specific experiences and psychosocial processes that may constitute risk and protective factors for suicide in this population. Drawing on theories of social inequality, medical sociology, and the stress process, we explore the adverse impact of gendered racism experiences and potential moderating factors in a sample of 204 predominantly low-SES African American women. We find that African American women’s risk for suicidal ideation is linked to stressors occurring as a function of their distinct social location at the intersection of gender and race. In addition, we find that gendered racism has no effect on suicidal ideation among women with moderate levels of well-being, self-esteem, and active coping, but has a strong adverse influence in those with high and low levels of psychosocial resources.

Keywords: Suicide, African American women, sexism, racism, self-esteem, active coping, well-being

In the U.S., African Americans have historically had lower rates of suicide than whites (Walker 2007). Consequently, there has been very little research to date on suicide risk among African Americans. The suicide-related mortality rate for African American women is low (1.9 per 100,000; CDC 2009) compared to both African American men (8.6 per 100,000) and white women (5.6 per 100,000). However, compared to their male counterparts, African American women have higher rates of suicide attempt (2.7% versus 5.0%, respectively) and ideation (10.2% versus 12.8%, respectively; Joe et al. 2006). Moreover, African American women have the highest incidence of medically treated suicide attempts (i.e., those with consequences severe enough to require medical intervention) among all race/gender subgroups (Spicer and Miller 2000). These patterns have prompted calls for research on culturally-specific factors contributing to suicidal ideation and behavior among African Americans (Joe et al. 2006; Utsey, Hook, and Stanard 2007). That is, additional research is needed to identify patterns of risk and coping strategies that may be specific to African Americans, and rooted in shared attitudes, values, and behaviors stemming from present and historical experiences living with pervasive racism and poverty (Fischer and Shaw 1999).

The purpose of this research is to improve our understanding of suicide risk among African American women. First, we begin with a discussion of African American women’s position at the intersection of multiple disadvantaged social statuses. Next, we argue that experiences associated with concurrent racism and sexism are substantial sources of stress in this population, increasing risk for psychological distress, disorder, and, ultimately, suicidal ideation. Then, we discuss the importance of coping resources and strategies in managing the emotional consequences of racism and sexism, highlighting ways in which these might operate in unique ways for African American women. Finally, using data from the B-WISE (Black Women in the Study of Epidemics) project, we assess whether suicidal ideation among a sample of predominantly low-income African American women is related to institutional and interpersonal experiences of concurrent racism and sexism. We then explore the extent to which exposure to these stressors is moderated by traditional psychosocial coping resources.

BACKGROUND

Gendered Racism as a Stressor

Sociologists argue that the organization of social life, systems of oppression, and opportunity structures available to members of different status groups in the U.S. result in predictable patterns of risks and stressors (Aneshensel, Rutterm, and Lachenbruch 1991). Recently, scholars have linked adverse health outcomes among African American women to their distinct status as both gender and racial minorities. Scholars Patricia Hill Collins and Kimberlé Crenshaw first employed the term “intersectionality” to describe the impact of multiple identities on experiences of inequality (Crenshaw 1991; Collins 1991). Focusing on African American women’s location at the intersection of disadvantaged gender, racial, and class statuses, their research demonstrates that oppression cannot be reduced to a single experience of one of these identities, i.e. sexism or racial discrimination. Rather, “the oppressions [associated with each of these disadvantaged statuses] work together in producing injustice” (Collins 2000). Essentializing and contradictory representations of African American women are pervasive in U.S. culture, both historically and into the present day. Commonly held stereotypes and media images portray them as dangerous, sexually promiscuous, and violent. Alternatively, African American women are viewed as “mammy figures” – nurturing, servile, and passive (Thomas et al. 2008). The confluence of these and other representations of African American womanhood and identity create a system of oppression that works to silence Black women, making them vulnerable to sexual violence, discrimination, and sexism in ways that white women are not (Collins 2000; Sue 2010).

Despite the importance of these ideas, surprisingly little empirical research has addressed the relationship between African American women’s mental health and their position at the intersection of multiple disadvantaged statuses, and none of this research specifically examines suicidal ideation. Research suggests that African American women experience a unique form of oppression that is specific to this group and is based in racist perceptions of gender roles (Jackson et al. 2001; Thomas et al. 2008). Racism is “an ideology of inferiority that is used to justify unequal treatment of members of groups defined as inferior, by both individuals and societal institutions (Williams 1999:177).” Racism is a structured aspect of life for African Americans, encompassing major events as well as everyday stressors associated with silent racism and more subtle forms of oppression and degradation (Sue 2010). For African American women, racism is compounded by a longstanding gender ideology that devalues women, resulting in an intersectional form of oppression that has been termed both racialized sexism (hooks and Mesa-Bains 2006) and gendered racism (Thomas et al. 2008).

For African American women, gendered racial identity has greater salience compared to the separate constructs of racial or gender identity, indicating that both of these social statuses simultaneously influence perceptions of self, responses to racialized and gendered stressors, and psychological distress (Thomas, Hacker, and Hoxha 2011). For example, using in-depth interviews with African American women, Jones and Shorter-Gooden (2003) comprehensively explored women’s experiences managing gendered racism. The authors found that African American women report frequent experiences of racism and sexism, and engage in multiple strategies to focus on and cope with both simultaneously. These efforts require identity and emotion work, often resulting in high levels of stress, maladaptive behaviors, and depression. Quantitative research supports these findings, suggesting that racism and sexism experiences are highly correlated, and that African American women are more likely to experience and be distressed by sexism and racism than white women and African American men, respectively (Greer, Laseter, and Asiamah 2009; King 2003; Moradi and Subich 2003). Similarly, the association between racism and mental health has been found to be stronger in women than in men (Borrell et al. 2006). In all, this literature underscores that racism and sexism combine to form a system of oppression (i.e. gendered racism) that operates distinctively among African American women, driving social psychological processes, behaviors, and interactions.

A key assertion of our research is that gendered racism contributes to adverse mental health outcomes among African American women, and that it is critical to explore the role of this stressor in explaining suicidal ideation. A wealth of evidence indicates that perceived racism is significantly associated with general psychological outcomes like subjective well-being, psychological distress, symptoms of anxiety or depression, and feelings of anger, threat, and harm (Brondolo et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2000; Pieterse et al. 2012). Though there is less evidence linking racism experiences to clinically diagnosable psychiatric disorders, studies suggest a possible relationship to major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and psychosis among African Americans (Brown et al. 2000; Karlsen et al. 2005; Kessler, Mickelson, and Williams 1999). In addition, psychologists have documented the traumatic nature of racist incidents, urging clinicians to broaden their conceptualization of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to encompass racism as a stressor (Bryant-Davis and Ocampo 2005). Likewise, sexism has been linked to multiple indicators of mental health and illness, including anxiety, anger, obsessive-compulsivity, somatic symptoms, and depression (Borrell et al. 2011; Klonoff, Landrine, and Campbell 2000). Though research on gendered racism or concurrent racism and sexism is much less prevalent, some studies do indicate that these experiences have adverse mental health consequences for African American women, increasing psychological distress and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Buchanan and Fitzgerald 2008; Moradi and Subich 2004). As noted previously, depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other mental health problems are strongly predictive of suicide risk (Moscicki 2001), suggesting that gendered racism may increase the likelihood of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among African American women through the stress process.

The Stress Process and African American Women’s Mental Health

Three decades ago, Pearlin and colleagues (1981) developed a model of the stress process – a sociological theory of social stressors and their consequences. Though it has since been extended or modified in a variety of ways (Clark et al. 1999; Pearlin et al. 2005; Williams and Mohammed 2009), the foundation of this theory rests on the relationship between sources, mediators, and manifestations of stress. Sources of stress may be either discrete events (e.g. getting fired from a job due to discrimination) or ongoing, chronic strains (e.g. being persistently devalued and dismissed by supervisors on the basis of race and/or gender), and these may work in conjunction such that major life events exacerbate preexisting strains or introduce new ones (Williams and Mohammed 2009). Stressors like gendered racism may lead to psychological distress and other adverse health outcomes. However, this is dependent on whether stress threatens an individual’s self-concept, and whether a person possesses social supports and coping resources with which to neutralize stress.

The stress process is particularly relevant to the experiences of low-SES African American women since a primary goal of the theory is explaining how social status hierarchies and inequality affect health (Pearlin 1999; Pearlin et al. 2005). Race and ethnicity embody access to power, economic resources, social capital, and cultural norms and values that pervade every component of the stress process (Clark et al. 1999; Williams and Mohammed 2009). Racial and socioeconomic stratification influences exposure and vulnerability to stressful events and environments in patterned ways (Aneshensel et al. 1991; Turner, Wheaton, and Lloyd 1995). In addition, Afrocentric cultural values and behaviors are frequently undervalued or even at odds with the dominant Eurocentric culture, leading to persistent threats to the self-concept and ethnic identity of African Americans (Walker 2007). Exposure to and internalization of stereotypes and prejudices may lead to low self-esteem, sense of mastery, and motivational deficits for individuals in low-status positions (Jang et al. 2003; Keyes 2009; Pearlin et al. 1981). Also, disadvantaged status groups often have limited access to resources for avoiding stressors and opportunities for managing emotional consequences of stress (Brondolo et al. 2009). Likewise, coping mechanisms may operate uniquely for people in different social positions such that certain resources may be more effective for men or women, whites or racial/ethnic minorities, etc. (Meyer, Schwartz, and Frost 2008). This can cause members of disadvantaged groups to modify their strategies for managing stress (Shorter-Gooden 2004).

Recently, researchers have become increasingly interested in the impact of stress on members of minority groups and their ability to successfully cope with high levels of stress. This interest derives, in part, from the “Black-White paradox” in mental health, wherein African Americans experience more negative life events and chronic stressors associated with their disadvantaged status, but tend to exhibit lower rates of mental illness (Keyes 2009). According to a 2006 study (Breslau et al.), non-Hispanic African Americans have a lower risk of generalized anxiety disorder, depression, social phobia, panic disorder, and early-onset impulse control disorders when compared to white Americans. As Keyes (2009) points out, while African Americans seem to experience greater rates of physical disease due to social inequality, discrimination, and other factors, they have higher rates of moderate to flourishing mental health when compared to whites – problematizing the stress process explanation of disparities in mental health. Similarly, Rosenfield and colleagues (2006) assert that African American women in particular, despite their disadvantaged location in the social hierarchy, have disproportionately few internalizing and externalizing problems, resulting in lower rates of mental illness.

That said, the key to understanding the relationship between racism and mental health may lie in the distinction between psychological distress and disorder. Namely, racism may increase risk for adverse psychosocial outcomes rather than clinically-diagnosable mental illness (Keyes 2009). As Keyes’ research suggests, the absence of diagnosed mental illness does not necessarily indicate the flourishing mental health of African Americans or benign consequences of racism. Psychological distress induced by racism can prevent African Americans from experiencing a sense of autonomy, self-acceptance, social integration, and mastery (Keyes 2009). For this reason, it is critical to examine variations in mental health outcomes – both psychosocial and clinical – within status groups as a function of differing levels of exposure to racism and other chronic stressors. In fact, Rosenfield and colleagues (2006) argue that African American women’s low rates of mental illness should not direct scholarly attention away from the inequality they experience. Rather, research should focus on coping mechanisms employed by African American women to better understand their resilience in the face of chronic race and gender-related stressors.

Psychosocial and Coping Resources Among African American Women

In social stress theory, the adverse impact of stressors is thought to be buffered by a number of protective factors (Brondolo et al. 2009; Pearlin 1999; Walker 2007). This is sometimes referred to as the transactional model of stress, wherein coping is defined as “cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific internal or external demands that are appraised as taxing (Lazarus and Folkman 1984:141).” Psychosocial resources are thought to operate through 1) modifying situations that give rise to stress (e.g. moving to a lower-crime neighborhood); 2) influencing the meaning of stressors such that they become less threatening (e.g. reframing job loss as an opportunity to seek better employment); or 3) reducing the level of psychological distress that occurs in response to the stressor (e.g. exercising to reduce tension). Thus, stressors should have a substantially reduced effect in the presence of these resources, which allow individuals to effectively manage or neutralize stress before it affects physical or psychological health.

Social supports have garnered a great deal of attention among stress researchers as a critical resource for managing stress (Pearlin 1999). People benefit from emotional support, advice, and affirmation provided by their personal networks, and social support has been linked to a variety of positive health outcomes in the presence and absence of stress (Lin and Peek 1999; Shorter-Gooden 2004). Relatedly, social integration and regulation have long been implicated as causal factors in suicide, dating back to Emile Durkheim’s seminal research (1951). According to Durkheim’s theory, individuals are less likely to commit suicide when they are bound to social groups and therefore to group values, norms, goals, and traditions. Social regulation provides a controlling influence on individuals, guiding their behavior through obligations to others and to the group. Others have expanded Durkheim’s concepts, arguing that the support and guidance associated with social integration fosters a sense of comfort and security that minimizes both real and perceived threats to well-being (Fothergill et al. 2011; Keyes 2009). Further, integration reinforces one’s belongingness to a group, which in turn affirms one’s sense of worth and positive identity.

Studies have examined the protective role of social support or integration on African American suicide (e.g., Willis et al. 2002), typically citing aspects of African American communities that constitute protective factors in this population. Specifically, African Americans tend to have more and stronger ties to kin than other races, and this pattern is thought to contribute to lower rates of suicide in this group (Barnes and Bell 2003; Utsey et al. 2008). Research suggests that African American women experiencing relationship discord and low levels of family social support and cohesion are at a higher risk for suicidal ideation and attempt (Compton, Thomson, and Kaslow 2005; Kaslow et al. 2000). Some research on African Americans indicates that being married is associated with lower levels of pro-suicide attitudes and lower risk of reported suicide (Stack and Wasserman 1995). However, others have argued that marriage is a less important factor in suicide risk for African Americans relative to whites because of their stronger ties to extended family (Stack 1996). Social support and integration into African American families and social networks may be protective because suicide is a non-normative response to psychological distress in the African American community, and cultural values and beliefs unique to this group may suppress suicidal ideation (Gibbs 1997).

Another psychosocial resource of particular relevance to African American women is existential well-being. Feelings of life satisfaction and purpose have been theorized to reduce the impact of discrimination and other stressors among minority groups (Ryff, Keyes, and Hughes 2003). Individuals who are generally happy with their lives may be less vulnerable to any individual stressor since they possess a more global feeling that things are going well. Likewise, they may be more optimistic, in general, and capable of reframing negative events as potential opportunities. Finally, people with a sense of well-being may be engaged in a variety of activities and roles that give their lives meaning, provide outlets for tension reduction, and bolster one’s self-concept. Research examining samples of college students (Hammermeister and Peterson 2001) and moderate-SES men (Tsuang et al. 2007) suggests that high levels of existential well-being are associated with decreased risk for major depression and substance abuse, and are associated with high self-esteem and general mental and physical health.

Self-esteem has also been implicated as an important component of the stress process, reducing self-reported level of stress and improving problem solving abilities (Bernichon, Cook, and Brown 2003; Lee-Flynn et al. 2011). In general, African American women and girls tend to report higher self-esteem compared to other racial/ethnic groups in nationally-representative samples, despite living in a Eurocentric culture characterized by persistent threats to a positive self-concept (Adams 2010). Along these lines, self-esteem has been found to moderate the relationship between racism and mental health outcomes among African American college students (Fischer and Shaw 1999). Thus, scholars argue that positive self-esteem among African Americans may operate similarly to existential well-being, activating and sustaining protective behaviors and attitudes in the face of stressful circumstances (Twenge and Crocker 2002).

Coping strategies may also help to neutralize stress by promoting effortful responses and effective problem resolution. Possessing an active coping style is thought to be a personality trait (Costa, Somerfield, and McCrae 1996), and is characterized by seeking out information, social support, and professional help to promote problem solving. African Americans with a strong behavioral disposition to directly manage an environmental stressor through hard work and determination (i.e. an active coping orientation) have been found to have positive health outcomes, though these findings are based on a non-representative sample with high levels of education (Fernander and Schumacher 2008).

Despite that existential well-being, self-esteem, and active coping are typically conceptualized as valuable resources in the stress process, the beneficial properties of these may not extend to members of lower status groups. Along these lines, research using random samples of African Americans suggests that an active orientation toward coping with racism may actually be detrimental to health, particularly among low-SES groups (Bennett et al. 2004; Dressler, Bindon, and Neggers 1998). According to the John Henryism hypothesis, African Americans with high active coping experience a strong desire to take effective action coupled with repeated failures due to persistent socioeconomic disadvantage or other barriers. Over time, this may lead to frustration, psychological distress, negative health behaviors, hypertension, and other adverse health outcomes (James 1994; Merritt et al. 2004). Likewise, studies suggest that African American women facing racism often prefer to employ an avoidant coping strategy to manage this stressor rather than an active one, perhaps because a more active orientation has proven ineffective and distressing in the past (Shorter-Gooden 2004; Thomas, Witherspoon, and Speight 2008). Social psychologists emphasize that the efficacy of coping resources depends on the match between the psychosocial characteristic or personality trait and the nature of the stressor (Lazarus 1999). In other words, psychosocial resources may not be a “one size fits all” good, and some traits may actually be harmful in certain stressful situations.

In sum, though African American women’s position at the intersection of multiple disadvantaged social statuses increases exposure to gendered racism experiences, empirical research has not examined the impact of these stressors on risk for suicide. With the exception of one historical and theoretical text (Poussaint and Alexander 2000), neither race scholars nor health researchers have directly considered racism or sexism as causal factors in African American suicide. Moreover, there is a need for research identifying coping resources that neutralize the impact of race or gender-related stressors, and exploring how these might operate in unique ways for African American women (Utsey et al. 2007; Walker 2007). To address these gaps in knowledge, we explore the effects of gendered racism experiences on suicidal ideation among predominantly low-income African American women. In addition, to better understand the culturally-specific pathways and conditions under which psychosocial and coping resources function as protective factors, moderation models are examined to explore whether these buffer the adverse impact of gendered racism.

METHODS

Sample

Data from the first wave of the B-WISE (Black Women in the Study of Epidemics) project are used for this analysis. The B-WISE study measures both protective and risk factors in the epidemiology of African American women’s physical and mental health outcomes. Parallel data are being collected from prisoners and probationers to make comparisons across criminal justice status. However, only the community sample is used in these analyses.

Participants in the community sample were recruited using newspaper ads and fliers posted in various parts of the city with a large African American population (based on 2000 U.S. Census data). Eligibility criteria included: (1) self-identifying as an African American woman; (2) being at least 18 years old; and (3) not currently being involved in the criminal justice system. In addition, because of the high rate of drug use among prisoners, substance-using women were oversampled. Specifically, a stratified sampling procedure was used such that women were placed into a drug user or non-drug user group based on self-reported past-year use of illicit substances. Women were recruited in the community until the target sample (100 women in each group) was reached. Eligible women participated in face-to-face interviews conducted by trained female African American interviewers in a private location.

After dropping two cases due to missing data, the final analysis sample contains 204 observations. Participants report an average of 12.75 years of education, and an average age of 36.39 years. The mean annual household income is $20,850, and 13% of the women in the sample are married. According to these descriptive statistics, women in the B-WISE sample are not representative of African American women nationally, but are similar to residents of the communities from which they were sampled (i.e., neighborhoods with high proportions of African American residents). The median household income in the sample ($17,500) and the percent college educated (15%) are significantly different from national statistics for African American women ($29,423; Z=−6.44; p<.001 and 24%; Z=2.57; p<.01), but not significantly different from the median in sampled communities (2000 U.S. Census). However, the percent currently married in the B-WISE sample (13%) is significantly different from both the national percentage and the percentage in the sampled zip codes (26%; Z=3.71; p<.001 and 29%; Z=4.57; p<.001, respectively; 2000 U.S. Census). In all, the results presented here are based on a sample with a lower socioeconomic status and marriage rate than all African American women living in the U.S.

In addition, because of the stratified sampling technique, about 50% of the sample report having used illegal drugs in the past year. However, only about one-third of the sample used drugs in the past month, and the majority of activity reported is occasional marijuana use as opposed to opiate dependence or use of other “hard” drugs. That said, since the high number of drug users in the sample could introduce bias, a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent has a self-reported lifetime history of illicit drug problems, abuse, or dependence is included in all models. Importantly, controlling for drug use does not alter the results or conclusions of this research.

Measures

Suicidality

A dummy variable measuring suicidal ideation is the key dependent variable in this research. The item asks whether a woman had ever experienced “serious thoughts of suicide,” including having a plan for taking her own life. The dummy variable is coded 1 if the respondent reports suicidal ideation, and 0 if not1.

Gendered racism

Experiences of gendered racism are measured using the Schedule of Sexist Events (SSE; Klonoff and Landrine 1995) and the Schedule of Racist Events (SRE; Landrine and Klonoff 1996). These instruments contain 13 and 17 items, respectively. They ask whether respondents ever experienced a series of events “because you are a woman” or “because you are black” (e.g., denial of raise or promotion; inappropriate or unwanted sexual advances; actual or threat of verbal or physical assault; unfair treatment by employers, teachers, coworkers, neighbors, friends, partners/significant others, etc.). These are combined into one scale of lifetime gendered racism experiences because 1) existing research and theory suggests that it is often difficult to distinguish whether unfair treatment is due to race or gender, and that these tend to be closely linked (e.g., King 2003; Thomas et al. 2008); 2) the racism and sexism scales are highly correlated (r=.61, p<.001) and contain numerous identical items that are strongly associated at a very low p-value; 3) when included separately in regression models, there is evidence of multicollinearity; 4) both scales are significant predictors of suicidality when included in two separate regression models; and 5) regressions using a combined gendered racism scale provide a better model fit than those with separate sexism and racism scales, as measured by the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Results are available upon request.

The SSE and SRE are measured on different Likert scales. The SSE is measured on a 4-point scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often), while the SRE is measured on a 6-point scale (never, once in a while, sometimes, a lot, most of the time, almost all of the time). Because of the conceptual similarity of the first three response categories of the SRE to the first three categories of the SSE, the SRE is truncated at a value of 4 such that a lot, most of the time, and almost all of the time are combined into one category. This recoding prevents racist events from being over-weighted in the scale. In addition, six items are identical across scales. These are averaged across scales to prevent a single event, which may have been perceived as both racism and sexism, from being over-weighted. For instance, if a respondent reports “rarely” experiencing unfair treatment by people in service jobs due to being a woman and “sometimes” due to being African American, that respondent would receive a mean of 2.5 on a metric with a potential range from 1-4. These combined items and the remaining unique items are summed to give a composite measure of gendered racism experiences2. The combined gendered racism scale is highly reliable, with an alpha of .90.

Socio-demographic and mental health control variables

In examining factors predicting suicidality, it is important to control for socioeconomic and mental health status. Suicidal ideation and behavior are defining features of some disorders, and it is estimated that over 90% of suicide victims have depression, anxiety, or some other psychiatric illness (Moscicki 2001; Walker and Hunter 2009). Relatedly, research has consistently demonstrated a strong positive relationship between socioeconomic status and mental health (e.g. Eaton and Muntaner 1999), and socioeconomic status may also play a role in vulnerability to and perceptions of racism (Foreman, Williams, and Jackson 1997; Sigenmal and Welch 1991).

Education and household income are employed to measure the impact of socioeconomic status on suicidality. Education is coded in years, with annual household income coded in thousands of dollars and logged to correct for positive skew. Alternative strategies for coding and operationalization were explored (e.g., personal income, being on public assistance, education level as a set of dummy variables), but did not improve model fit. In addition, age was included in regression models to control for life course differences in SES and mental health. This variable is coded in tens of years.

Two dummy variables measure mental health and substance abuse history. The mental health variable is assessed using one item and is coded 1 if a respondent reports that she has a lifetime history of “nervous or mental health problems.” Similarly, the substance abuse variable is coded 1 if a woman reports a history of “illicit drug problems, abuse or dependence.”. A variety of different measures of mental health problems (e.g., self-reported anxiety and depression) and illicit drug use (e.g., past year and past month drug use defined using various combinations of items asking about specific drugs) were initially included in regression analyses. However, the two variables described above are retained in final models because choice of measures does not impact the effects of other independent variables and these indicators provide the best model fit.

Social supports

Three variables are included in models to capture social supports. A single dummy variable measures marital status (1=currently married; 0=separated, widowed, divorced, or never married). Though separate dummy variables for separated, widowed, and divorced were initially included, these did not improve model fit over the simpler coding. In addition, perceived social support from family and friends are also included in this analysis. Social support is measured using the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS; Zimet et al. 1988), which includes 4 items measuring support from family members (e.g., “My family really tries to help me”) and 4 from friends (e.g., “I can count on my friends when things go wrong”). Responses are measured on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). Both the family (alpha=.94) and friend (alpha=.94) support scales are highly reliable and range from 4 to 28.

Existential well-being

Existential well-being is a scale comprised of twelve items that measures a person’s sense of purpose and life satisfaction (Ellison 1993). It includes items like “I feel good about my future,” and “I believe there is some real purpose for my life.” Response categories range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), and negatively worded statements are reverse coded. Responses to all items are summed such that higher values correspond to a greater sense of well-being. This scale is highly reliable (alpha=.85) and has a potential range from 12 to 72.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem is measured using the 10-item Rosenberg scale. It includes such items as “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself” and “I take a positive attitude toward myself” (Rosenberg 1979). Responses vary from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with negative items reverse coded. Responses are summed such that higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. This scale is highly reliable (alpha=.87) and has a potential range from 10 to 40.

Active coping orientation

A 12-item active coping (i.e., John Henryism) scale measures ability to respond proactively to challenges (James, Hartnett, and Kalsbeek 1983) focusing on three reinforcing ideas: a commitment to hard work, effective mental and physical strength to accomplish everyday life tasks, and perseverance to achieve individual goals (e.g., “Once I make up my mind to do something, I stay with it until the job is complete”). Responses range from 1 (completely false) to 5 (completely true), with negative items reverse coded and higher scores signifying a more active coping orientation. This scale has a potential range from 12 to 60, and is highly reliable (alpha=.76).

Analysis

Analyses presented here explore relationships between gendered racism experiences, psychosocial resources, social supports, and suicidal ideation. To determine the extent to which gendered racism experiences predict suicidal ideation binary logistic regression models are computed using Stata 11. A baseline model regresses suicidality on the gendered racism life events scale, controlling for socioeconomic status, age, and mental health history. Then, sets of variables measuring psychosocial resources and social supports are added to the baseline model, allowing for identification of potential mediating relationships. Specifically, if the coefficient for gendered racism becomes non-significant or decreases in magnitude with the inclusion of covariates, there may be a mediating effect that requires further analysis using the Baron and Kenny (1986) method. Mediation models are an important tool because they allow the researcher to test whether a particular variable influences the outcome of interest through a third variable.

To explore whether psychosocial resources and social supports moderate the relationship between gendered racism and suicidality, models with interaction terms are explored. These determine whether gendered racism has unique effects at different levels of a given covariate, and are essential for testing stress-buffering influences. One set of multiplicative terms (gendered racism*categorical covariate) is added to the baseline model, and this is repeated for each covariate. Categorical variables are created by dividing the distribution into three approximately equal groups using tertiles. Only significant interactions are presented in tables and text. To facilitate interpretation of interactive models, figures of predicted probabilities are presented following the regression results.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Results indicate that almost 20% of the low-SES African American women in the sample report having seriously considered or attempted suicide in their lifetimes. Additionally, negative life events attributed to sexism and/or racism are a regular feature of African American women’s experiences ( =14.23). With respect to mental health history, about 32% of the sample report illicit drug problems and 22% report significant mental health problems. Despite these risk factors, descriptive statistics also indicate the presence of considerable resources. For instance, the mean level of existential well-being is 55.56, self-esteem is 32.46, and active coping is 50.84, suggesting that women in the sample report a moderate level of psychosocial coping resources. Similarly, while only 13% of women in the sample are currently married, the mean perceived social support is 21.55 from family and 21.60 from friends, suggesting a strong support system.

Table 1.

Descriptive sample characteristics (B-WISE, n=204)

| Proportion | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | 0.17 | |||

| Gendered racism | 14.23 | 9.35 | 0.00-46.50 | |

| Education (years) | 12.75 | 2.26 | 3.00-20.00 | |

| Household income (thousands) | 20.85 | 21.24 | 2.50-87.50 | |

| Age (years) | 36.39 | 14.19 | 18.00-68.00 | |

| Mental health history | ||||

| Illicit drug problems | 0.32 | |||

| Mental health problems | 0.22 | |||

| Psychosocial resources | ||||

| Well-being | 55.56 | 9.45 | 22.00-72.00 | |

| Self-esteem | 32.46 | 5.22 | 21.00-40.00 | |

| Active coping | 50.84 | 5.89 | 33.00-60.00 | |

| Social supports | ||||

| Currently married1 | 0.13 | |||

| Family support | 21.55 | 6.48 | 4.00-28.00 | |

| Friend support | 21.60 | 5.93 | 4.00-28.00 |

Table 2 presents results from logistic regression models examining the effects of gendered racism, socioeconomic status, mental health, and psychosocial resources on suicidal ideation. According to Model 1, the baseline model, experiencing higher levels of gendered racism events is associated with a significant increase in the odds of reporting suicidal thoughts (OR=1.06, p<.01), all else equal. The predicted probability of reporting suicidal ideation at one standard deviation below the mean gendered racism score is 8%, compared to 13% at the mean and 21% at one standard deviation above the mean. Also, women with a self-reported history of mental health problems are estimated to be over four times more likely than those without to experience suicidal thoughts or planning (OR=4.29, p<.001). Having a history of mental health problems is associated with an increase of .21 in the predicted probability of suicidal ideation. Education, logged household income, age, and drug problems do not achieve significance in this model.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of suicidal ideation on gendered racism, psychosocial resources, and social supports (B-WISE, n=204)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gendered racism | 1.06 (1.02-1.10)** | 1.05 (1.01-1.10)* | 1.06 (1.01-1.11)** | 1.06 (1.01-1.11)** |

| Education (years) | 0.95 (0.80-1.14) | 0.98 (0.80-1.20) | 0.95 (0.79-1.14) | 0.95 (0.77-1.18) |

| Logged HH income ($K) | 0.75 (0.49-1.16) | 0.84 (0.53-1.34) | 0.78 (0.50-1.22) | 0.85 (0.53-1.37) |

| Age (tens of years) | 0.92 (0.67-1.26) | 0.88 (0.62-1.24) | 0.93 (0.67-1.28) | 0.90 (0.64-1.27) |

| Mental health history | ||||

| Illicit drug problems | 0.89 (0.37-2.14) | 0.62 (0.23-1.66) | 0.87 (0.35-1.15) | 0.64 (0.23-1.75) |

| MH problems | 4.29 (1.83-10.05)*** | 4.39 (1.79-10.81)*** | 4.32 (1.82-10.24)*** | 4.86 (1.92-12.25)*** |

| Psychosocial resources | ||||

| Well-being | 0.93 (0.88-0.99)* | 0.92 (0.86-0.99)* | ||

| Self-esteem | 1.06 (0.94-1.20) | 1.07 (0.94-1.21) | ||

| Active coping | 0.93 (0.86-1.00) | 0.93 (0.86-1.01) | ||

| Social supports | ||||

| Currently married1 | 0.58 (0.14-2.45) | 0.46 (0.10-2.18) | ||

| Family support | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) | 1.01 (0.93-1.09) | ||

| Friend support | 1.01 (0.94-1.10) | 1.03 (0.95-1.12) | ||

|

| ||||

| LRX2 | 28.37*** | 40.88*** | 29.35*** | 42.79*** |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.23 |

Omitted categories: Widowed, separated, divorced, never married

=p<.05;

=p<.01;

=p<.001 (two-tailed tests)

Note: Odds ratios are presented, confidence intervals in parentheses

According to Model 2, which adds measures of psychosocial resources, women with higher levels of existential well-being are predicted to be less likely to have thoughts of suicide (OR=0.93, p<.05). The predicted probability of reporting suicidal ideation at one standard deviation below the mean well-being score is 21%, compared to 12% at the mean and 7% at one standard deviation above the mean. Active coping and self-esteem do not achieve statistical significance. This is consistent with the psychosocial resources hypothesis and provides modest evidence for a transactional stress model. Also, the addition of psychosocial resources does not substantially diminish the influence of gendered racism, providing no support for a mediating model.

Surprisingly, findings in Model 3 provide no evidence for direct effects of social supports. That is, being currently married, perceived social support from family members, and perceived social support from friends have no statistically significant influence on suicidal ideation in this sample. These variables also do not diminish the effects of gendered racism. In the full model (See Model 4), gendered racism, mental health problems, and well-being continue to demonstrate statistically significant effects on the predicted odds of suicidal ideation.

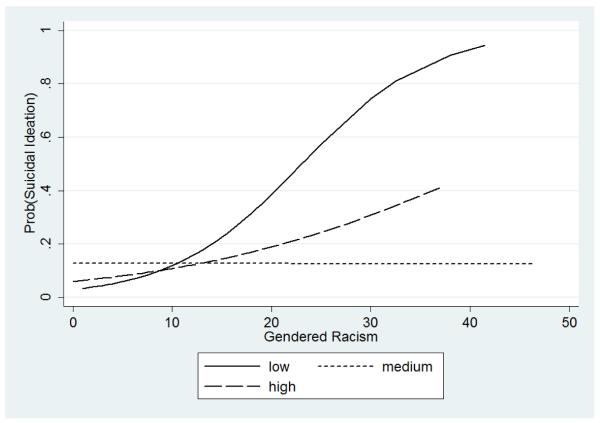

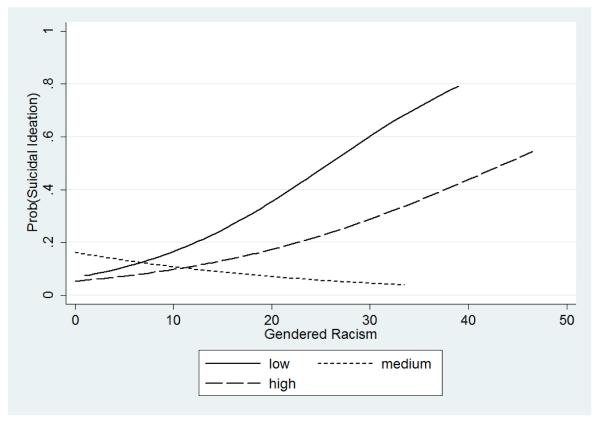

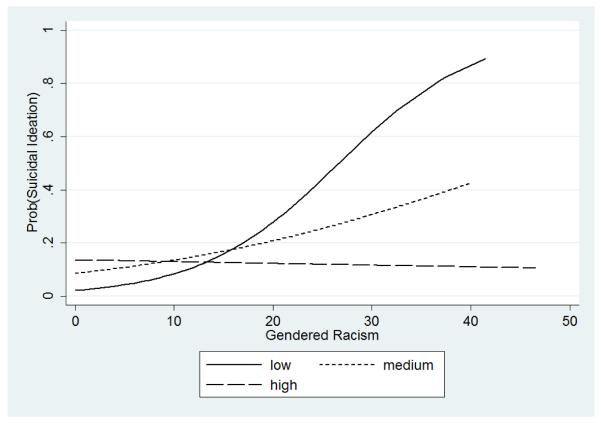

Table 3 presents results from interaction models exploring the moderating effects of psychosocial resources in the relationship between gendered racism and suicidal ideation. According to Model 1, well-being buffers the negative impact of gendered racism, as evidence by a significant interaction term (p<.05). A figure of changes in the predicted probability of suicidality as a function of gendered racism experiences by low, medium, and high well-being is presented in Figure 1. The predicted probability of suicidality increases as gendered racism events increase for both those with low and high levels of well-being, while this stressor has a slightly negative impact among those with medium levels. Self-esteem exhibits a similar relationship to that of well-being (see Model 2 and Figure 2), as does active coping (see Model 3 and Figure 3). That is, medium levels of self-esteem (p<.01) and active coping skills (p<.05) completely moderate the impact of gendered racism on suicidal ideation, while the influence of gendered racism at high levels is statistically indistinguishable from that at low levels. Thus, while those with a high degree of psychosocial resources have lower predicted overall odds of suicidal ideation compared to those with few resources, gendered racism has a strong adverse effect in both groups. Remarkably, among those with the lowest levels of psychosocial resources and the most severe exposure to gendered racism, the predicted probability of suicidal ideation is near or exceeds 80%. In contrast, medium levels of psychosocial resources buffer the effects of this stressor.

Table 3.

Interaction models examining the moderating effects of psychosocial resources and social supports in the relationship between gendered racism experiences and suicidal ideation (B-WISE, n=204)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gendered racism | 1.09 (1.02-1.16)* | 1.18 (1.07-1.31)*** | 1.10 (1.02-1.17)** | 1.18 (1.06-1.31)** |

| Well-being1 | ||||

| Mod well-being | 2.76 (0.36-20.76) | |||

| High well-being | 0.11 (0.01-1.54) | |||

| Mod*GR | 0.87 (0.77-0.99)* | |||

| High*GR | 0.99 (0.89-1.11) | |||

| Self-esteem1 | ||||

| Mod self-esteem | 10.18 (0.90-114.81) | |||

| High self-esteem | 3.81 (0.32-45.54) | |||

| Mod*GR | 0.82 (0.72-0.94)** | |||

| High*GR | 0.90 (0.79-1.02) | |||

| Active coping1 | ||||

| Mod active coping | 2.06 (0.22-19.01) | |||

| High active coping | 0.63 (0.09-4.51) | |||

| Mod*GR | 0.85 (0.73-0.99)* | |||

| High*GR | 0.96 (0.88-1.06) | |||

| Family support1 | ||||

| Mod social support | 13.07 (0.92-186.58) | |||

| High social support | 11.81 (0.80-174.61) | |||

| Mod*GR | 0.87 (0.76-0.99)* | |||

| High*GR | 0.85 (0.75-0.97)* | |||

|

| ||||

| LRX2 | 48.11*** | 42.94*** | 43.20*** | 37.92*** |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.20 |

Omitted categories: Low

=p<.05;

=p<.01 (two-tailed tests)

Note: Odds ratios are presented, confidence intervals in parentheses; all models control for education, income, age, mental health problems, and illicit drug problems

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of suicidal ideation as a function of gendered racism experiences by low, medium, and high well-being

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of suicidal ideation as a function of gendered racism experiences by low, medium, and high self-esteem

Figure 3.

Predicted probability of suicidal ideation as a function of gendered racism experiences by low, medium, and high active coping

Finally, we find that medium and high levels of family social support moderate the adverse effect of gendered racism on suicidality (p<.05; see Table 3, Model 4). As shown in Figure 4, gendered racism has no impact on suicidal ideation among African American women with high levels of family support, a moderate influence among those with medium levels, and a very strong effect for those without a family safety net. For women with low family support at the highest level of gendered racism events, the predicted probability of reporting suicidal ideation is nearly 90%.

Figure 4.

Predicted probability of suicidal ideation as a function of gendered racism experiences by low, medium, and high family social support

DISCUSSION

This research examines African American women’s risk and protective factors for suicidal ideation– an outcome reported by almost one-fifth of the women surveyed. Results provide evidence for a strong, positive association between negative life events attributed to gendered racism and risk for suicidality in this sample of predominantly low-income African American women. Notably, gendered racism exhibits this influence above and beyond socioeconomic status, mental health and substance abuse history, and a number of potential coping resources. This finding is consistent with existing research on the adverse impact of discrimination on the health of racial and ethnic minorities (Pieterse et al. 2012). However, this analysis adds a gender component, and also extends this body of literature to suicide – a topic rarely empirically investigated in African American women.

Sociologists argue that health disparities in America are largely attributable to the organization of social life, systems of oppression, and opportunities and resources available to members of different status groups (Aneshensel et al. 1991). An individual’s combination of intersecting statuses results in patterned experiences and identities, which increase or decrease vulnerability to a range of risk and protective factors. Though these ideas have roots in classic social theory (see Simmel 1955), relatively little sociological research explicitly examines the consequences of being positioned at the intersection of two or more disadvantaged social statuses. For African American women, their status as both racial/ethnic minorities and women constitutes a unique form of gendered racial oppression such that the stratifying effects of racism and sexism cannot be distinguished (Jackson et al. 2001; King 2005; Thomas et al. 2008). Moreover, longitudinal studies of health and illness underscore the importance of explicitly modeling intersectionality rather than simply controlling for socio-demographic variables (Hinze, Lin, and Anderson 2012; Warner and Brown 2011). This research demonstrates that the effect of gender or socioeconomic status may vary across racial and ethnic groups, and that African American women experience cumulative disadvantage over the life course that renders them uniquely susceptible to physical and mental health problems in old age. In other words, examining racism or sexism in isolation can obscure the magnitude of the impact of social status on health.

Insights from the stress process suggest a number of pathways through which gendered racism experiences could lead to suicidal ideation and behavior in African American women. First, persistent devaluation on the basis of gender and race can cause women to internalize negative stereotypes, posing a threat to positive self-concept, sense of control, proactive coping, and other social psychological resources (Aneshensel et al. 1991). Second, gendered racism may affect mental health through maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., excessive drug or alcohol consumption) and other behavioral pathways. Finally, as a source of stress, gendered racism can have direct adverse effects on cognitive and emotional functioning through psychobiological pathways, including acute neuroendocrine response and allostatic load (Massey 2004). Over time, brain structure permanently adapts to severe and chronic stress, making individuals less cognitively resilient and more vulnerable to psychological disorder in response to subsequent stressors (Fremont and Bird 2000). As a pervasive feature of the social condition of African American women, exposure to gendered racism can shape biological processes in ways that critically determine individuals’ subsequent health trajectories and well-being.

Psychosocial Resources and Coping as Protective Factors for African American Women

A goal of this research was to better understand the culturally-specific pathways and conditions under which psychosocial and coping resources function as protective factors for African American women. Consistent with this aim, the direct and stress-buffering effects of social supports on suicidal ideation were assessed. Durkheim’s theory of social integration and regulation suggests that individuals are less likely to commit suicide when they are bound to social groups and therefore to group values, norms, goals, and traditions. Consistent with Durkheim’s theory, African Americans’ lower overall rates of suicide have been attributed to their more cohesive family social support system relative to other race/gender subgroups (Barnes and Bell 2003). Indeed, empirical research indicates that marriage (Stack and Wasserman 1995) and family social support and cohesion (Kaslow et al. 2000) are factors that decrease the likelihood of suicide among African Americans. However, our findings do not demonstrate a statistically significant direct influence of any of these factors on the odds of suicidal ideation among African American women. There may have been insufficient variation to capture the direct effects of social supports due to the measures used or the relatively small sample size.

That said, our results did identify a significant moderating effect of family social support, echoing a wealth of research on the stress-buffering effects of social networks (for a review, see Lin and Peek 1999). Specifically, experiencing additional negative events attributed to gendered racism has no perceptible influence among African American women with high family social support, a modest effect among those with moderate levels of support, and a very strong effect in women with no family-based social safety net. Consistent with this finding, there is some indication in the existing literature that social support from other African Americans may be a crucial resource in coping with racism and related stressors (Utsey et al. 2008). For example, Lalonde and colleagues (1995) found that because racism is often less tangible and more insidious than other stressors, seeking social support from similar others is a preferred coping strategy and sometimes the only available option. Disclosing these experiences with other African Americans who share a collective ethnic identity may promote feelings of acceptance and belonging, minimizing the adverse impact of racial and gender oppression. Likewise, spending enjoyable leisure time with family members may provide a respite from the stress associated with gendered racism and minimize the likelihood of maladaptive coping processes.

Moreover, as suggested by the transactional model of stress (Lazurus and Folkman 1984), we find that traditional psychosocial resources have a protective effect on risk for suicidality in African American women. Existential well-being demonstrates direct ameliorative effects on the odds of suicidal ideation. In addition, well-being, self-esteem, and active coping are all found to have a moderating or buffering effect in the presence of a powerful social stressor. Specifically, gendered racism experiences have no adverse influence in the presence of these resources, which may allow African American women to manage or neutralize stress that would otherwise lead to suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Pearlin 1999).

Yet, contrary to expectations, the buffering effects of these psychosocial resources are only evident at medium levels of well-being, self-esteem, and active coping. In other words, we find no support for a buffering effect at low or high levels of these resources, though women with high well-being have smaller predicted probabilities of suicide risk overall relative to those with low levels. Given that this finding extends to all of the psychosocial resources measured here, it is not likely a statistical anomaly. However, much of the previous work demonstrating only positive effects of psychosocial resources has been conducted in moderate or high-SES samples that include men and whites. Consequently, the patterns found here may be attributable to the lower social status of women in the B-WISE sample relative to African American women in the U.S. as a whole. Specifically, high levels of well-being, self-esteem, and active coping among largely unmarried, low-SES, African American women may lead to distress and frustration in the face of persistent and degrading racial stereotypes, discrimination experiences, and personal failures and setbacks.

Consistent with this explanation, our results on high active coping find some support in the literature on John Henryism and racial disparities in the prevalence of hypertension. For African Americans, an active coping orientation is a common response to psychosocial stressors, including racism (Plummer and Slane 1996). This trait is thought to have emerged following the civil war as a cultural adaptation to “pervasive and deeply entrenched systems of social and economic oppression (James 1994, p. 167).” In many instances, John Henryism (also known as active coping) is a productive response to tractable problems. However, research indicates that low-SES African Americans with a tendency to engage in high-effort coping exhibit a stronger and more prolonged cardiovascular response to psychosocial stressors, increasing their likelihood of developing high blood pressure over time (Merritt et al. 2004). That is, for individuals with little access to economic, social, and cultural capital, high levels of John Henryism are maladaptive, resulting in persistent cognitive and emotional engagement with challenges despite a low probability of achieving a successful outcome (James 1994).

Though much of this work focuses on hypertension, the hypothesis is applicable to a range of health conditions (James 1994). Thus, for the primarily lower-income African American women in our sample, an active coping orientation is unlikely to buffer the adverse impact of race and gender-related psychosocial stressors that are largely uncontrollable and perhaps unavoidable. In contrast, and consistent with findings presented here, John Henryism combined with repeated gendered racism experiences may increase the odds of prolonged frustration, anger, despair, and ultimately suicidal ideation.

Similarly, psychosocial traits like high self-esteem and existential well-being may not be universally adaptive, despite the overwhelming portrayal of these as markers of psychological health (Jordan et al. 2003). For instance, Kernis and Paradise (2002) argue that high self-esteem comes in two very different forms – secure and defensive. While some individuals are genuinely confident in their positive views of self, others hold positive self-images that are fragile and vulnerable to external threats. According to Jordan and colleagues (2003), defensive self-esteem occurs when individuals hold conflicting views of self. That is, these individuals possess a conscious, external view characterized by feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy, but simultaneously harbor less conscious, internal feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt. Such individuals often become defensive and distressed in the face of personal failures and challenges because of the fragile state of their external, positive self-worth.

Social and cultural mechanisms may increase the likelihood that African American women experience a conflicted, fragile self-esteem and sense of existential well-being. For example, African American women face persistent threats to positive self-concept in the form of gendered racism. These experiences may lead to the internalization of racist and sexist beliefs about their intrinsic worth and undermine the formation of secure self-esteem (Williams and Williams-Morris 2000). Additionally, Poussaint and Alexander (2000) argue that cultural norms inhibit African American women from openly expressing weakness in the face of hardship, instead encouraging and rewarding power and invulnerability. Consequently, many African American women report an internalized obligation to “bear up,” or display a guise of strength, which may manifest as defensive self-esteem (Boyd 1998). Thus, among African American women with conflicting views of self or underlying feelings of inadequacy, high self-esteem is unlikely to buffer the adverse effects of gendered racism. Rather, for these individuals, being humiliated and devalued on the basis of race and gender may constitute a severe threat to a fragile self-concept, increasing the likelihood of suicidal ideation.

Limitations and Future Directions

This research has several notable limitations. Specifically, the data used here are not based on a nationally representative sample of African American women. The marriage rates, percent college educated, and household income are lower than national averages for African American women based on U. S. Census reports. These differences are likely due to sampling procedures. That is, women were recruited largely in communities with a high proportion of African Americans, suggesting that the findings may be representative of African American women living in economically depressed, racially segregated neighborhoods. In addition, because the community sample was drawn to make comparisons to a sample of women in prison, a disproportionate percentage of respondents are illicit drug users. It is important to note that controlling for income, education, and drug use did not change the substantive findings. However, readers should use caution when interpreting results, and be aware that findings may not extend to African American women in higher socioeconomic strata. Given these methodological limitations, a key contribution of this study is to serve as a starting point for more in-depth, longitudinal, nationally-representative research on risk and resilience factors for suicide in African American women.

Also, it is possible that some latent variable explains the relationship between gendered racism and suicidal ideation. For instance, a trait such as pessimism may be associated both with psychological well-being and the likelihood of perceiving racism and sexism in interpersonal and institutional interactions. While this possibility cannot be excluded, empirical evidence indicates that, in general, people are remarkably accurate at identifying instances of personal and group discrimination (Taylor, Wright, and Porter 1994). That said, factors like cynical hostility, self-esteem, perceived control, and coping mechanisms may affect how individuals perceive and react to gendered racism, which in turn can influence their impact on suicidality (Clark et al. 1999). Future research should examine the extent to which these resources and risk factors predict reports of racist and sexist life events.

In sum, despite these limitations, this research responds to recent calls for attention to social predictors of suicidality among African American women (Utsey et al. 2007; Walker 2007), contributing to theories of African American suicide and the relatively small empirical literature on this topic. These findings improve our understanding of the combinations of culturally-specific experiences and psychosocial processes that constitute risk and protective factors for suicide among African American women. Specifically, we find that African American women’s risk for suicide is linked to stressors occurring as a function of their distinct social location at the intersection of gender and race. Moreover, moderate levels of psychosocial resources buffer the adverse impact of gendered racism, while high and low levels do not. These results are provocative and may be unique to this population, contributing to more nuanced social psychological theories of stress and coping.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA22967).

NOTES

An additional variable asking about suicidal gestures or attempts (suicidal behavior) was explored. When suicidal behavior and ideation are combined into one dummy variable, results mirror those presented for ideation alone. Results for suicidal behavior (9% of the sample) alone are in the same direction as findings for the combined measure, but the gendered racism variable achieves statistical significance only in the baseline model. We conducted rare events logistic regression given the small number of respondents reporting suicidal behavior, but results did not differ from logistic regression estimates. Because these analyses suggest that suicidal ideation is driving the significance of the effects for the combined measure in the current analysis, we have decided to present models for suicidal ideation alone. Full results are available upon request.

Several different coding strategies for gendered racism were attempted, including a series of dummy variables, inclusion of a polynomial term to capture potential nonlinearity, and separation of number of types of gendered racism experienced from frequency of experiences. Because the continuous measure provided optimal model fit, this was retained in final regression models. In addition, because some research has suggested that the effect of racism and sexism may be multiplicative rather than additive (Anderson and Collins 2004; Moradi and Subich 2003; Thomas, Witherspoon, and Speight 2008), interaction models multiplying racism experiences by sexism experiences using continuous and dummy variable methods were also examined. These did not produce any evidence of a significant interaction. Results are available upon request.

Contributor Information

Brea L. Perry, University of Kentucky

Erin Pullen, University of Kentucky.

Carrie B. Oser, University of Kentucky

REFERENCES

- Adams Portia E. Understanding the Different Realities, Experience, and Use of Self-Esteem Between Black and White Adolescent Girls. Journal of Black Psychology. 2010;36:255–76. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel Carol S., Rutter Carolyn M., Lachenbruch Peter A. Social Structure, Stress, and Mental Health: Competing Conceptual and Analytic Models. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:166–78. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes Donna Holland, Bell Carl C. Paradoxes of Black Suicide. National Journal. 2003;20:2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Baron Reuben M., Kenny David A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Gary G., Merritt Marcellus, Sollers John J., Edwards Christopher L., Whitfield Keith E., Brandon Dwayne T., Tucker Reginald D. Stress, Coping, and Health Outcomes among African Americans: A Review of the John Henryism Hypothesis. Psychological Health. 2004;19:369–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bernichon Tiffiny, Cook Kathleen E., Brown Jonathon D. Seeking Self-Evaluative Feedback: the Interactive Role of Global Self-Esteem and Specific Self-Views. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:194–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell Luisa N., Kiefe Catarina I., Williams David R., Diez-Roux Ana, Gordon-Larsen Penny. Self-Reported Health, Perceived Racial Discrimination, and Skin Color in African Americans in the CARDIA Study. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:1415–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell Carme, Artazcoz Lucia, Gil-Gonzelez Diana, Perez Katherine, Perez Gloria, Vives-Cases Carmen, Rohlfs Izavella. Determinants of Perceived Sexism and Their Role on the Association of Sexism with Mental Health. Women & Health. 2011;51(6):583–603. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.608416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd Julia A. Can I Get a Witness? For Sisters When the Blues Is More Than a Song. Dutton; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau Joshua, Aguilar-Gaxiola Sergio, Kendler Kenneth S., Su Maxwell, Williams David, Kessler Ronald C. Specifying Race-Ethnic Differences in Risk for Psychiatric Disorder in a USA National Sample. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth Brondolo, Thompson Simon, Brady Nicholas, Appel Roland, Cassells Andrea, Tobin Jonathan. The Relationship of Racism to Appraisals and Coping in a Community Sample. Ethnicity and Disease. 2005;15:14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Tony N., Williams David R., Jackson James S., Neighbors Harold W., Torres Myriam, Sellers Sherrill L., Brown Kendrick T. Being Black and Feeling Blue: The Mental Health Consequences of Racial Discrimination. Race and Society. 2000;2:117–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis Thema, Ocampo Carlota. Racist Incident-Based Trauma. The Counseling Psychologist. 2005;33:479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan Nicole T., Fitzgerald Louise F. Effects of Racial and Sexual Harassment on Work and the Psychological Well-Being of African American Women. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2008;13:137–51. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.13.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Centers for Injury Prevention and Control [Retrieved May 21, 2012];Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) 2009 ( www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars)

- Clark Rodney, Anderson Norman B., Clark Vernessa R., Williams David R. Racism as a Stressor for African Americans. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–16. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Collins Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (Revised Tenth Anniversary Edition) 2 ed Routledge; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Compton Michael, Thomas Nancy J., Kaslow Nadine J. Social Environment Factors Associated with Suicide Attempt among Low-Income African Americans: The Protective Role of Family Relationships and Social Support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40:175–85. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Paul T., Somerfield Mark R., McCrae Robert R. Personality and Coping: A Reconceptualization. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications. Wiley; New York: 1996. pp. 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw Kimberlé. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review. 1991;43:1241–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler W, Bindon JR, Neggers YH. John Henryism, Gender, and Arterial Blood Pressure in an African American Community. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60:620–24. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim Émile. Suicide. Free Press; New York: 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Fernander Anita, Schumacher Mitzi. An Examination of Socio-Culturally Specific Stress and Coping Factors on Smoking Status among African American Women. Stress and Health. 2008;24:365–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Ann R., Shaw Christina M. African Americans’ Mental Health and Perceptions of Racist Discrimination: The Moderating Effects of Racial Socialization Experiences and Self-Esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Fremont Allen M., Bird Chloe E. Social and Psychological Factors, Physiological Processes, and Physical Health. In: Bird C, Conrad P, Fremont A, editors. Handbook of Medical Sociology. Prentice-Hall; Upper Saddle River: 2000. pp. 334–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill Kate E., Ensminger Margaret E., Robertson Judy, Green Kerry M., Thorpe Roland J., Juon Hee-Soo. Effects of Social Integration on Health: A Prospective Study of Community Engagement among African American Women. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:291–98. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs Jewelle T. African American Suicide: A Cultural Paradox. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1997;27:68–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer Tawanda M., Laseter Adrian, Asiamah Davis. Gender as a Moderator of the Relation between Race-Related Stress and Mental Health Symptoms for African Americans. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33:295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hammermeister Jon, Peterson Margaret. Does Spirituality Make a Difference? Psychosocial and Health-Related Characteristics of Spiritual Well-Being. American Journal of Health Education. 2001;32:293–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hinze Susan W., Lin Jielu, Andersson Tanetta E. Can We Capture the Intersections? Older Black Women, Education, and Health. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- hooks bell, Mesa-Bains Amalia. Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism. South End Press; Cambridge: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Fleda M., Phillips Mona T., Hogue Carol J., Curry-Owens Tracy Y. Examining the Burdens of Gendered Racism: Implications for Pregnancy Outcomes among College-Educated African American Women. Maternal and Child Health Journals. 2001;5(2):95–107. doi: 10.1023/a:1011349115711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James Sherman, Hartnett Sue., Kalsbeek William. John Henryism and Blood Pressure Differences among Black Men. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1983;6:259–78. doi: 10.1007/BF01315113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James Sherman A. John Henryism and the health of African Americans. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 1994;18:163–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01379448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Yuri, Borenstein-Graves Amy, Haley William E., Small Brent J., Mortimer James A. Determinants of a Sense of Mastery in African American and White Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58:S221–24. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.s221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Lifetime Suicide Attempts among Blacks in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:2112–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Charisse, Shorter-Gooden Kumea. Shifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in America. Harper Collins; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan Christian H., Spencer Steven J., Zanna Mark P., Hashino-Browne Etsuko, Correll Joshua. Secure and Defensive High Self-Esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003:969–78. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen Saffron, Nazroo James Y., McKenzie Kwame, Bhui Kamaldeep, Weich Scott. Racism, Psychosis and Common Mental Disorder among Ethnic Minority Groups in England. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:1795–1803. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow Nadine J., Thompson Martie, Meadows Lindi, Chance Susan, Puett Robin, Hollins Leslie, Jessee Sally, Kellermann Arthur. Risk Factors for Suicide Attempts among African American Women. Depression and Anxiety. 2000;12:13–20. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1<13::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernis Michael H., Paradise Andrew W. Distinguishing between Secure and Fragile Forms of High Self-Esteem. In: Deci EL, Ryan RM, editors. Handbook of Self-Determination Research. University of Rochester Press; Rochester: 2002. pp. 339–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C., Mickelson Kristin D., Williams David R. The Prevalence, Distribution, and Mental Health Correlates of Perceived Discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes Corey L.M. The Black-White Paradox in Health: Flourishing in the Face of Social Inequality and Discrimination. Journal of Personality. 2009;77(6):1677–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King Kimberly R. Racism or Sexism? Attributional Ambiguity and Simultaneous Membership in Multiple Oppressed Groups. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:223–47. [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff Elizabeth A., Landrine Hope. The Schedule of Sexist Events: A Measure of Lifetime and Recent Sexist Discrimination in Women’s Lives. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19:439–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde Richard N., Majumder Shilpi, Parris Roger D. Preferred Responses to Situations of Housing and Employment Discrimination. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1995;25:1105–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus Richard S. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. Springer; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus Richard S., Folkman Susan. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Spring Publishing Company; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Flynn Sharon C., Pomaki Georgia, DeLongis Anita, Biesanz Jeremy C., Puterman Eli. Daily Cognitive Appraisals, Daily Affect, and Long-Term Depressive Symptoms: The Role of Self-Esteem and Self-Concept Clarity in the Stress Process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37(2):255–68. doi: 10.1177/0146167210394204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Nan, Peek M. Kristen. Social Networks and Mental Health. In: Horwitz Allan V., Scheid Teresa L., editors. A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas. Segregation and Stratification: A Biosocial Perspective. Du Bois Review. 2004;1:7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt Marcellus M., Bennett Gary G., Williams Redford B., Sollers John J., Thayer Julian F. Low Educational Attainment, John Henryism, and Cardiovascular Reactivity to and Recovery from Personally Relevant Stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:49–55. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000107909.74904.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Ilan H., Schwartz Sharon, Frost David M. Social Patterning of Stress and Coping: Does Disadvantaged Social Statuses Confer More Stress and Fewer Coping Resources? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:368–79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi Bonnie, Subich Linda Mezydlo. A Concomitant Examination of the Relations of Perceived Racist and Sexist Events to Psychological Distress for African American Women. The Counseling Psychologist. 2003;31:451–69. [Google Scholar]

- Moscicki Eve K. Epidemiology of Completed and Attempted Suicide: Toward a Framework for Prevention. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2001;1:310–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I., Schieman Scott, Fazio Elena M., Meersman Stephen. Stress, Health, and the Life Course: Some Conceptual Perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I. Stress and Mental Health: A Conceptual Overview. In: Horwitz Allan V., Scheid Teresa L., editors. A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 161–75. [Google Scholar]