Abstract

Background

AxiaLIF was initially advocated as a minimally invasive, presacral lumbar fusion approach. Its use has expanded in to adult scoliosis surgeries.

Methods

Current literature about AxiaLIF for degenerative lumbar surgery and adult scoliosis surgery were reviewed. Anatomy, biomechanical properties, clinical results, and complications were summarized.

Results

Anatomically, AxiaLIF is relatively safe even though traversing blood vessels, and the pelvic splanchnic nerve can be at risk. AxiaLIF can provide significant stiffness compared to the intact spine, but posterior supplementation is recommended. AxiaLIF in the long construct for adult scoliosis surgeries can protect the S1 screw as effectively as pelvic fixation. Successful clinical outcomes after AxiaLIF were reported in the degenerative lumbar spine, adult scoliosis, and spondylolisthesis. It can facilitate a high fusion rate up to 96 % without BMP. Complications include pseudarthrosis, rectal injury, transient nerve irritation, and intrapelvic hematoma.

Conclusion

AxiaLIF is a relatively safe procedure, and it provides good clinical results in both short constructs and long constructs for adult scoliosis surgery. For a safer procedure, surgeons should seek out prior colorectal surgical history and review preoperative imaging studies carefully.

Keywords: Axial lumbar interbody fusion (AxiaLIF), Adult scoliosis, Anatomy, Outcome, Complications

Introduction

In a long-construct fusion for adult scoliosis, choosing correct levels and correct fixation methods are critical in obtaining optimal outcome. In the presence of spondylolisthesis, stenosis, prior laminectomy, or oblique take-off at L5–S1, fusion to the sacrum is recommended [5]. Fusion to the sacrum in a long construct can be complicated with S1 screw failure, thus leading to pseudarthrosis with or without a focal kyphotic deformity at the L5–S1 level. Traditionally, protection of the S1 screw can be obtained by the Galveston technique [3], four rod technique [26], S2 screws [23], S1 iliac screws [6], and S2 alar iliac screws [21]. More recently, AxiaLIF has been used as an augmentation method to protect S1 screws in the long construct for adult scoliosis, and its biomechanical and clinical usefulness have been proved [2].

In this article, a brief review of the anatomic consideration of AxiaLIF, its biomechanical properties in short or long constructs, its surgical indications and technique after adult scoliosis correction, and its clinical outcomes in both degenerative lumbar and adult scoliosis surgeries will be discussed.

Anatomic consideration

Safety and feasibility are always an issue for any innovative technique. The advantage of AxiaLIF is its percutaneous approach; therefore, the anatomic safety is most critical. Cragg et al. [8] performed a feasibility study of AxiaLIF in cadaver, animal, and three human pilot patients. They performed the procedure successfully in all three groups, and no patient had vascular or neural injuries. Luther et al. [19] reported the increased safety of the AxiaLIF by way of using the neuronavigation system.

More recently, Li et al. [17] did an extensive cadaver study on the anatomy of the AxiaLIF approach. They illustrated five layers of the presacral fascial structures: periosteum, the parietal presacral fascia, the rectosacral fascia, autonomic nerve fascia, and the fascia propria of the rectum. They advocated that surgeons should pay attention to traverse veins and the pelvic splanchnic nerves. Injury of these structures can cause pelvic hematoma and sexual/urinary dysfunction.

Biomechanical properties

Ledet et al. [16] compared the various biomechanical properties of the AxiaLIF with those of multiple preexisting fixation methods including cages, plates, and rod systems in bovine lumbar motion segments. Results showed a significant increase in stiffness in AxiaLIF fixation compared to the intact specimen. AxiaLIF fixation showed significantly higher stiffness than all other cage designs in terms of lateral and sagittal bending motion. In extension and axial compression, axial fixation also showed comparable stiffness to plate and rod constructs. They concluded that axial placement provides favorable biomechanical properties compared to other fixation methods.

This result was reproduced in other studies. Akesen et al. [1] performed the biomechanical studies of AxiaLIF in human cadavers and showed that stand-alone transsacral fixation significantly reduced the range of motion of segments. They demonstrated that the advantage of axial fixation is leaving the annulus intact and achieving indirect decompression with distraction. In order to obtain the optimal biomechanical properties, however, they recommended that posterior fixation, such as facet screws or pedicle screws, should be added.

Erkan et al. [10] showed similar results in two-level axial fixation. The stand-alone axial two-level fixation showed a reduced range of motion compared to the intact specimen, but posterior supplemental fixation showed better stiffness than the stand-alone axial two-level fixation.

More recently, a biomechanical study of AxiaLIF in a long construct was performed in human cadaveric spine [11]. Fleischer and co-authors compared the S1 screw strain among four different constructs: pedicle screw alone (L2–S1), pedicle screw with an anterior interbody device, pedicle screw with axial fixation, and pedicle screw with iliac screws. The results showed that S1 screw strain was the greatest in pedicle screw alone, decreased by 38 % after anterior interbody augmentation, decreased by 75 % after using axial fixation, and decreased by 78 % after iliac screw augmentation. The study demonstrated that AxiaLIF can provide similar biomechanical properties compared to iliac screw fixation in terms of protecting the S1 screw in long constructs. Based on this biomechanical study, our site uses unilateral iliac screw fixation for osteopenic patients with BMD indicating osteopenia and use bilateral iliac screws for patients with osteoporosis. However, we do not use any iliac screws for patients with normal BMD.

Surgical indication and technique for AxiaLIF after adult scoliosis correction

Surgical indication for additional anterior fusion after adult scoliosis correction is indicated by: (1) a lumbosacral fractional curve; (2) a big body habitus; and (3) severe spinal stenosis needing decompression. In any case where decompression is needed due to severe stenosis, we can substitute AxiaLIF for another anterior fusion procedure such as TLIF or PLIF. Typically, 2 levels are done when there is good trajectory from the sacrum to the L4 body and if the patient requires an interbody at L4–5. If there is a fractional lumbosacral curve that requires correction, a TLIF to horizontal the L4 level is done alongside a one-level AxiaLIF at L5–S1. Presence or absence of lumbar lordosis at L4–S1 is not critical since we can obtain segmental lumbar lordosis with any anterior fusion technique including TLIF or AxiaLIF.

The surgical technique is similar to the usual AxiaLIF technique for a lumbar degenerative condition. 24 h before the procedure, every patient undergoes a colonoscopy with Golytle bowel prep. AxiaLIF is done under the same posterior deformity correction anesthesia. The patient is kept on the Jackson table, but one more pillow is put underneath the hips to maximize hip flexion. Two C-arms are needed to simultaneously see AP and lateral views. The patient is draped again, then a transverse incision is made on the right buttock next to the coccygeal area. Previously, skin was cut longitudinally, but a transverse incision reduces dehiscent due to the pressure of sitting. First a finger dissection is done all the way into the coccyx then a blunt dissector is inserted. The tract is expanded via the expander, followed by screws and final cage insertion. Not only can you distract the segment, but you can also create lordosis. A one-level AxiaLIF usually takes 40 min to one hour.

Clinical results

Since Cragg et al. [8] reported the feasibility of AxiaLIF on three pilot patients, many studies reported the clinical outcomes and the complications regarding AxiaLIF [15, 20, 25]. Patil et al. [25] reported a 96 % fusion rate in 50 patients with an average follow-up of 12 months, and Aryan et al. [4] reported a 91 % fusion rate after AxiaLIF in 21 patients.

More recently, clinical outcomes with more than 2 years follow-up were reported. Tobler et al. [29], in their retrospective review, reported the clinical and the radiographic results of 156 AxiaLIF cases with 86 % pain and 74 % function clinical success rates. Their radiographic fusion rate was 94 %, which was similar to the previous reports [25]. Tobler et al. [28] also performed prospective studies at 2-year follow-up with 26 cases and reported that significant improvement in pain and function in the first 3 months was maintained. Radiographic fusion was obtained in 22 patients (92 %) at 1 year and in 23 patients (96 %) at 2 years. They had one pseudarthrosis which was revised successfully with the augmentation of a posterolateral fusion mass.

Tender et al. [27] reported the successful outcome of AxiaLIF in three degenerative spondylolisthesis spines, and Gerszten et al. [13] reported successful outcomes in 26 low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. Gerszten et al. [12] also reported that clinical outcomes were the same in the patients who underwent AxiaLIF with or without rhBMP-2, suggesting that AxiaLIF surgery can obtain good fusion while avoiding the complications caused by using rhBMP-2.

Anand et al. [2] combined three minimally invasive spine techniques (XLIF, AxiaLIF, and posterior percutaneous fixation) in 12 lumbar degenerative scoliosis patients and reported the results. Modest scoliosis correction was achieved with less morbidity and low blood loss which supports the rationale of AxiaLIF in adult scoliosis surgeries (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

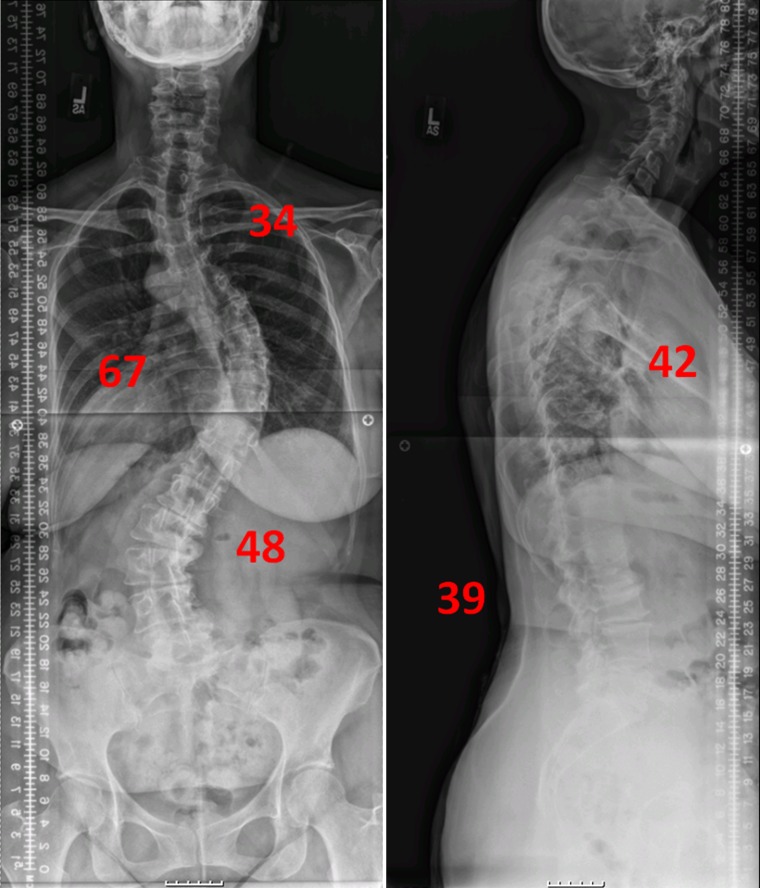

Fig. 1.

59-year-old female patient was presented with 67° of right thoracic curve and 48° of left lumbar curve. Preoperative SRS score was 2.9 total, and ODI was 46 %

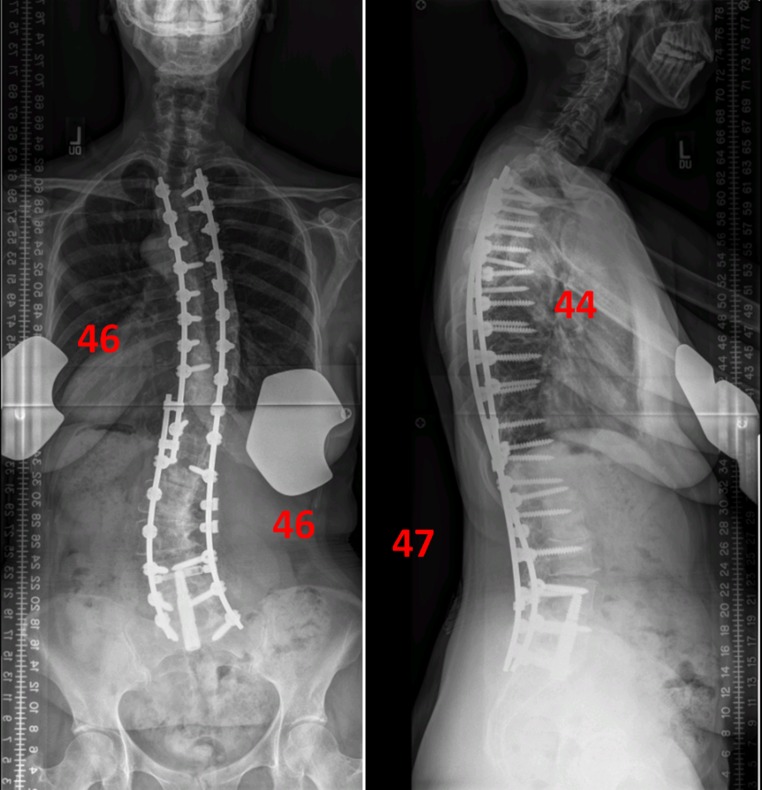

Fig. 2.

Standing X-rays at 6 months after surgery. The surgery was posterior multiple Ponte osteotomies and pedicle screw fixation from T3 to S1, and AxiaLIF was performed for two bottom levels of the construct (L4–S1) without inserting iliac screw. X-rays show the good coronal and sagittal balance with intact instrumentation. 6-month SRS score was 4 total, and ODI was 22 %

Fig. 3.

66-year-old female patient was presented with the chief complaint of back pain, loss of height, and inability of lift. Preoperative X-rays show 74° of left convex thoracolumbar curve and 65° of thoracic kyphosis

Fig. 4.

Two months after surgery, standing X-rays show intact instrumentation construct with unilateral pelvic fixation

Complications

Patil et al. [25] defined the most common complications as superficial wound infections, followed by pseudarthrosis, rectal injury, hematoma, and the irritation of a nerve root by a screw.

Lindley et al. [18] reported relatively low complication rates (26.5 %) in 68 AxiaLIF patients. They experienced 18 complications in 16 patients including psuedarthrosis (8.8 %), superficial infection (5.9 %), sacral fracture (2.9 %), pelvic hematoma (2.9 %), failure of wound closure (1.5 %), transient nerve root irritation (1.5 %), and rectal perforation (2.9 %). Regarding rectal perforation, Meyer and Mummaneni pointed out that AxiaLIF performed in outpatient clinics can be a problem considering the possibility of intrapelvic hematoma. They also emphasized that obtaining prior colorectal surgery history is important because it can cause adhesion. Careful review of preoperative imaging is also important [22]. Botolin et al. reported rectal injury during AxiaLIF thus strongly recommending a pelvic MRI or CT with contrast for patients who have had any possible abdominal adhesion [4].

Regarding AxiaLIF revision surgery, safety can be a concern because a previous surgical scar can cause possible rectal injury. DeVine et al. [9] reported on an AxiaLIF psuedarthrosis revision where a paramedian approach was performed and the AxiaLIF cage was removed through the anterior L5–S1 disc space. Regarding this innovative technique, Nasca [24] commented that the removal of an AxiaLIF cage through the previous presacral approach tract has been safe in 50 removals out of 8,600 AxiaLIF cases. Hofstetter et al. [14] also reported the feasibility of AxiaLIF cage removal percutaneously. Cohen et al. [7] reported on a revision which needed a wider cage for instability after a fall. He suggested the same presacral surgical approach for the AxiaLIF revision.

So far, we have performed about 65 cases in adult scoliosis patients. Most recently, we performed a study on 40 consecutive patients who underwent AxiaLIF after adult scoliosis correction (unpublished data). There were 25 patients with a one-level AxiaLIF and 15 patients with a two-level AxiaLIF. 9 out of 40 patients (22.5 %) had complications including: 3 transient radiculopathy, 2 thromboembolic events, 3 wound issues, and 1 implant malposition. 4 out of 40 (10 %) returned to the OR: 1 implant was repositioned, and 3 patients required superficial wound irrigation and debridement. There were no instances of deep-wound infections, bowel perforation, permanent neurologic, or vascular injuries in the series.

Conclusion

AxiaLIF is a relatively safe procedure and has provided good clinical results in short and long constructs for adult scoliosis surgery. In terms of S1 screw protection, it is as effective as pelvic fixation and equates to less blood loss and less morbidities as a minimally invasive procedure. Unless there is severe spinal stenosis requiring direct decompression, it can also provide indirect decompression and facilitate a successful fusion even without BMP. A comprehensive assessment of patient history and thorough diagnostic studies are mandatory to perform the procedure safely and to achieve a successful outcome.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Akesen B, Wu C, Mehbod AA, Transfeldt EE. Biomechanical evaluation of paracoccygeal transsacral fixation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21:39–44. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3180577242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand N, Baron EM, Thaiyananthan G, Khalsa K, Goldstein TB. Minimally invasive multilevel percutaneous correction and fusion for adult lumbar degenerative scoliosis: a technique and feasibility study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21:459–467. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318167b06b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen BL, Jr, Ferguson RL. The Galveston experience with L-rod instrumentation for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;229:59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aryan HE, Newman CB, Gold JJ, Acosta FL, Jr, Coover C, Ames CP. Percutaneous axial lumbar interbody fusion (AxiaLIF) of the L5-S1 segment: initial clinical and radiographic experience. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51(4):225–230. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridwell K, Edwards C, Lenke L. The pros and cons to saving the L5-S1 motion segment in a long scoliosis fusion construct. Spine. 2003;28(20S):S234–S242. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000092462.45111.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridwell KH, Kuklo T, Edwards CC., II . Sacropelvic fixation. Memphis: Medtronic Sofamor Danek; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen A, Miller LE, Block JE. Minimally invasive presacral approach for revision of an Axial Lumbar Interbody Fusion rod due to fall-related lumbosacral instability: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2011;5:488. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cragg A, Carl A, Casteneda F, Dickman C, Guterman L, Oliveira C. New percutaneous access method for minimally invasive anterior lumbosacral surgery. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17:21–28. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVine JG, Gloystein D, Singh N. A novel alternative for removal of the AxiaLif (TranS1) in the setting of pseudarthrosis of L5-S1. Spine J. 2009;9:910–915. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.08.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erkan S, Wu C, Mehbod AA, Hsu B, Pahl DW, Transfeldt EE. Biomechanical evaluation of a new AxiaLIF technique for two-level lumbar fusion. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:807–814. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-0953-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleischer GD, Kim YJ, Ferrara LA, Freeman AL, Boachie-Adjei O (2011) Biomechanical analysis of sacral screw strain and range of motion in long posterior spinal fixation constructs: effects of lumbosacral fixation strategies in reducing sacral screw strains. SpineLook for published date [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Gerszten PC, Tobler WD, Nasca RJ. Retrospective analysis of L5-S1 axial lumbar interbody fusion (AxiaLIF): a comparison with and without the use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Spine J. 2011;11:1027–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerszten PC, Tobler W, Raley TJ, Miller LE, Block JE, Nasca RJ. Axial presacral lumbar interbody fusion and percutaneous posterior fixation for stabilization of lumbosacral isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;25(2):E36–40. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318233725e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofstetter CP, James AR, Härtl R. Revision strategies for AxiaLIF. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31:E17. doi: 10.3171/2011.8.FOCUS11139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ledet EH, Carl AL, Cragg A. Novel lumbosacral axial fixation techniques. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2006;3:327–334. doi: 10.1586/17434440.3.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledet EH, Tymeson MP, Salerno S, Carl AL, Cragg A. Biomechanical evaluation of a novel lumbosacral axial fixation device. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127:929–933. doi: 10.1115/1.2049334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li XM, Zhang Li, Hou ZD, Wu T, Ding ZH. The relevant anatomy of the approach for axial lumbar interbody fusion. Spine. 2011;37(4):266–271. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821b8f6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindley EM, McCullough MA, Burger EL, Brown CW, Patel VV. Complications of axial lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:273–279. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.SPINE10373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luther N, Tomasino A, Parikh K, Härtl R. Neuronavigation in the minimally invasive presacral approach for lumbosacral fusion. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009;52:196–200. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1239504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marotta N, Cosar M, Pimenta L, Khoo LT. A novel minimally invasive presacral approach and instrumentation technique for anterior L5-S1 intervertebral discectomy and fusion: technical description and case presentations. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E9. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matteini LE, Kebaish KM, Volk WR, Bergin PF, Yu WD, O’Brien JR. An S-2 alar iliac pelvic fixation. Technical note. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28(3):E13. doi: 10.3171/2010.1.FOCUS09268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer SA, Mummaneni PV. Axial interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:271–272. doi: 10.3171/2011.1.SPINE10913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirkovic S, Abitbol JJ, Steinman J, Edwards CC, Schaffler M, Massie J, Garfin SR. Anatomic consideration for sacral screw placement. Spine. 1991;6(6S):S289–S294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasca RJ. Re: “a novel alternative for removal of the AxiaLIF (TranS1) in the setting of pseudarthrosis of L5-S1”. Spine J. 2010;10:945–946. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patil SS, Lindley EM, Patel VV, Burger EL. Clinical and radiological outcomes of axial lumbar interbody fusion. Orthopedics. 2012;33:883. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20101021-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen FH, Harper M, Foster WC, Marks I, Arlet V. A novel “four-rod technique” for lumbo-pelvic reconstruction: theory and technical considerations. Spine. 2006;31(12):1395–1401. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000219527.64180.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tender GC, Miller LE, Block JE. Percutaneous pedicle screw reduction and axial presacral lumbar interbody fusion for treatment of lumbosacral spondylolisthesis: a case series. J Med Case Reports. 2011;5:454. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobler WD, Ferrara LA. The presacral retroperitoneal approach for axial lumbar interbody fusion: a prospective study of clinical outcomes, complications and fusion rates at a follow-up of two years in 26 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:955–960. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B7.25188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobler WD, Gerszten PC, Bradley WD, Raley TJ, Nasca RJ, Block JE. Minimally invasive axial presacral L5-S1 interbody fusion: two-year clinical and radiographic outcomes. Spine. 2011;36:E1296–E1301. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821b3e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]