Abstract

Novel D- and L-4′-thioadenosine derivatives lacking the 4′-hydroxymethyl moiety were synthesized, starting from D-mannose and D-gulonic γ-lactone, respectively, as potent and selective species-independent A3 adenosine receptor (AR) antagonists. Among the novel 4′-truncated 2-H nucleosides tested, a N6-(3-chlorobenzyl) derivative 7c was the most potent at the human A3 AR (Ki = 1.5 nM), but a N6-(3-bromobenzyl) derivative 7d showed the optimal species-independent binding affinity.

Introduction

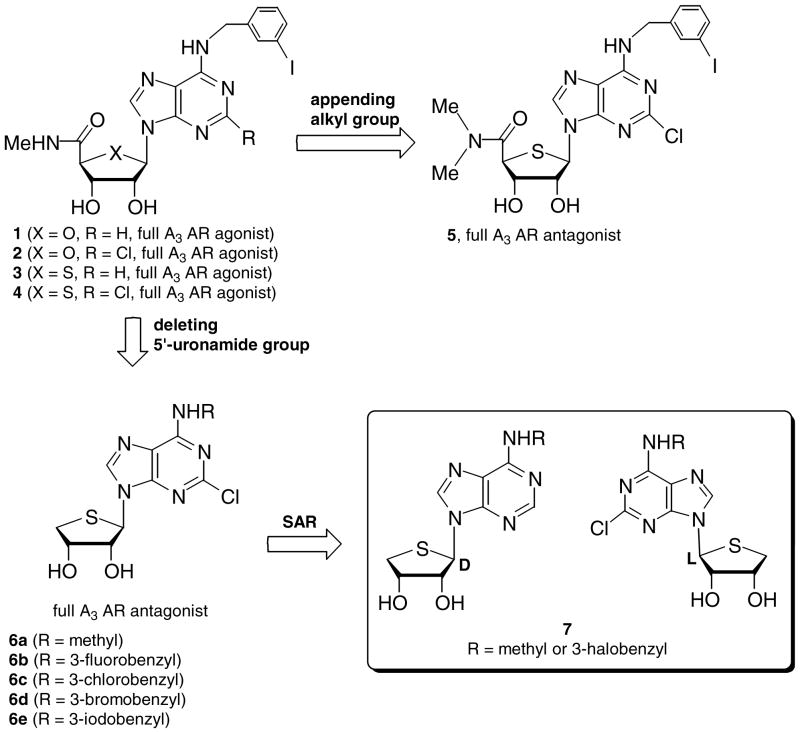

On the basis of the structure of adenosine, an endogenous cell signaling molecule that binds to four specific subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) of adenosine receptors (ARs)2, a number of nucleoside analogues have been synthesized and evaluated as adenosine receptor ligands.3 Among these, IB-MECA4 1 and Cl-IB-MECA5 2 were discovered as potent and selective A3 AR full agonists (Ki = 1.0 and 1.4 nM, respectively, at the human A3 AR) and are being developed as antiinflammatory and anticancer agents. Based on the bioisosteric rationale, we reported the 4′-thionucleosides 3 and 4, derivatives of compounds 1 and 2, to also be highly potent and selective A3 AR full agonists.6 Compound 4 exhibited potent in vitro and in vivo antitumor activities,7 resulting from the inhibition of Wnt signaling pathway (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

The rationale for the design of the target nucleosides 7.

However, because of the structural similarity to adenosine, most of these adenosine analogues were found to be A3 AR agonists. Only a few nucleoside derivatives8 have been reported to be A3 AR antagonists, but these generally exhibit weaker and less selective human A3 AR antagonism than nonpurine heterocyclic A3 AR antagonists. Although these nonpurine heterocyclic A3 AR antagonists9 bound with high affinity at the human A3 AR, they were weak or ineffective at the rat A3 AR, indicating that they were not ideal for evaluation in small animal models and thus as drug candidates.10 Therefore, it is highly desirable to develop A3 AR antagonists that are independent of species. The fact10 that nucleoside analogues show minimal species-dependence at the A3 AR prompted us to search for novel potent and selective A3 AR antagonists, derived from nucleoside templates.

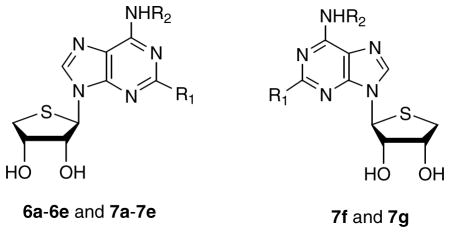

A molecular modeling study of the A3 AR indicated that hydrogen of the 5′-uronamides of compounds 1–4 serves as a hydrogen-bonding donor in the binding site of the A3 AR, which is essential for the induced-fit required for the activation of the A3 AR.11 On the basis of these findings, we appended extra alkyl groups on the 5′-uronamides of compounds 1–4 to remove hydrogen-bonding ability at this site, thus precluding the conformational change required for activation of the A3 AR. As expected, these 5′-N,N-dialkyl amide derivatives12 displayed potent and selective A3 AR antagonism, in which steric factors were crucial for affinity in binding to the A3 AR. Within this class, 5′-N,N-dimethylamide derivative 5 was discovered to be the most potent full A3 AR antagonist. Encouraged with these results, we designed and synthesized another new template to remove the 5′-uronamide group of compound 4 in order to minimize the steric repulsion at the binding region of the 5′-uronamide group and to abolish its hydrogen-bonding ability. This led to the discovery of compounds 6a – 6e as highly potent and selective human A3 AR antagonists, which was more potent and selective than compound 5.1 Among these, compound 6e also showed species-independent binding affinity, as indicated by its high affinity at the rat A3 AR.1 On the basis of these results, it is of interest to systematically establish structure-activity relationships by modifying the C2 and N6 positions of the purine moiety of compounds 6a – 6e in order to develop novel A3 AR antagonists. In this article, we extend previous observations that truncated D-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 6a – 6e containing 2-Cl substitution are selective A3 AR antagonists.1 A series of 2-H analogues were prepared and characterized biologically. The binding affinities at the human A3 AR were compared with those at the rat A3 AR to develop species-independent A3 AR antagonists. We also compared the binding affinities of D-4′-thionucleosides with those of the corresponding L-4′-thionucleosides to determine a stereochemical preference. Thus, here we report a full account of truncated D- and L-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 7 as highly potent and species-independent A3 AR antagonists.

Results and discussion

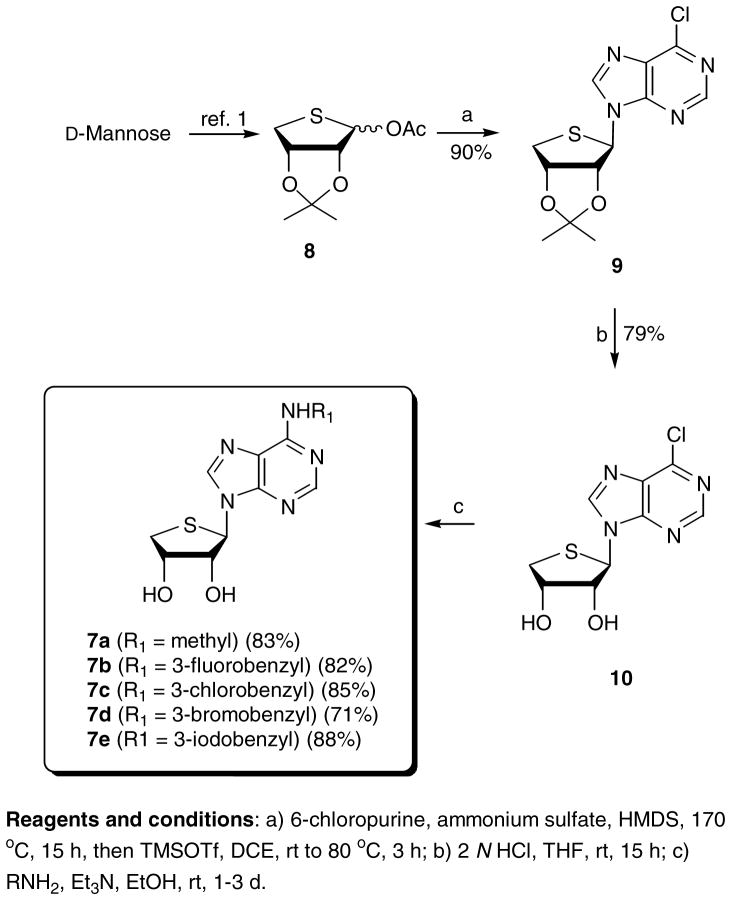

The D-glycosyl donor 8 was subjected to the Lewis acid-catalyzed condensation for the synthesis of the final D-4′-thionucleosides lacking a 4′-hydroxymethyl group, as shown in Scheme 1. The D-glycosyl donor 8 was condensed with 6-chloropurine in the presence of TMSOTf as a Lewis acid to give β-6-chloropurine derivative 9 as a single diastereomer. The anomeric configuration of compound 9 was easily confirmed by 1H NOE experiment between 3′-H and H-8. Removal of the isopropylidene group of 9 was achieved with 2 N HCl in THF to give 10. The 2-H intermediate 10 was converted to the novel N6-methyl derivative 7a and N6-3-halobenzyl derivatives 7b – 7e by treating with methylamine and 3-halobenzylamines, respectively. This route parallels the synthesis of the 2-chloro-N6-susbtituted-4′-thiopurine analogues 6a – 6e that we reported earlier1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of truncated D-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 7a–7e.

Reagents and conditions: a) 6-chloropurine, ammonium sulfate, HMDS, 170 °C, 15 h, then TMSOTf, DCE, rt to 80 °C, 3 h; b) 2 N HCl, THF, rt, 15 h; c) RNH2, Et3N, EtOH, rt, 1–3 d.

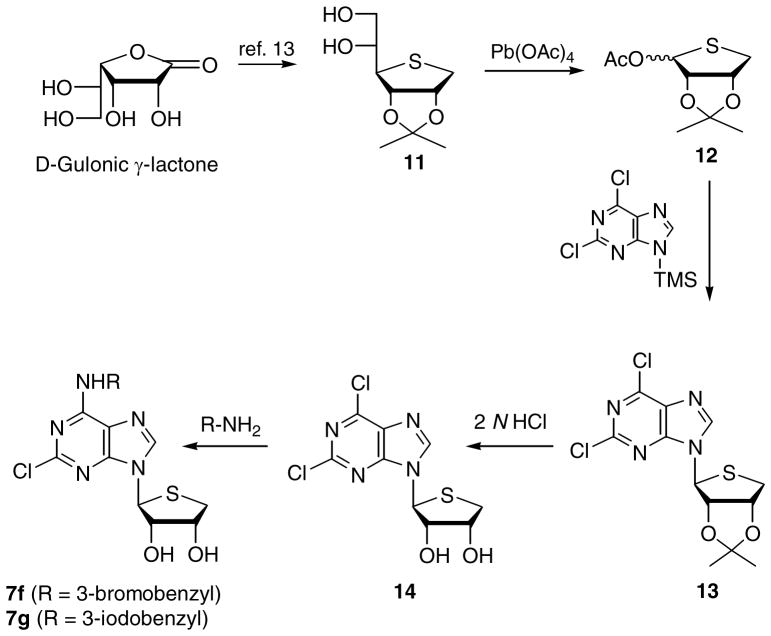

In order to determine whether a stereochemical preference exists in the binding to the A3 AR, the L-enantiomers, 7f and 7g of D-4′-thionucleosides were synthesized as illustrated in Scheme 2. D-Gulonic γ-lactone was converted to the diol 11 according to our previously published procedure.13 One-step conversion of the diol 11 into the L-glycosyl donor 12 was achieved using excess Pb(OAc)4, indicating that oxidative diol cleavage, oxidation of the resulting aldehyde to the acid, and oxidative decarboxylation occurred simultaneously.13 Using the same synthetic strategy shown in Scheme 1, L-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 7f and 7g were synthesized from L-glycosyl donor 12.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of truncated L-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 7f and 7g.

Initial binding experiments were performed using adherent mammalian cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding the appropriate human ARs (A1 AR and A3 AR in CHO cells and A2A AR in HEK-293 cells).14,15 Binding was carried out using 1 nM [3H]CCPA, 10 nM [3H]CGS-21680, or 0.5 nM [125I]I-AB-MECA as radioligands for A1, A2A, and A3 ARs, respectively. As shown in Table 1, most of the synthesized compounds exhibited high binding affinity at the human A3 AR with low binding affinities at the human A1 AR and human A2A AR. Among the novel 2-H truncated adenosine derivatives tested, compound 7c (R = 3-chlorobenzyl) showed the highest binding affinity (Ki = 1.5 ± 0.4 nM) at the human A3 AR with high selectivities versus the A1 AR (570-fold selective) and the A2A AR (290-fold selective). Compound 7e (R = 3-iodobenzyl) was also very potent (Ki = 2.5 ± 1.0 nM), with selectivities of 210- and 92-fold versus the A1 and A2A AR, respectively. N6-Substituted adenosine derivatives 7a – 7e without a 2-chloro substituent showed a very similar pattern to the corresponding 2-chloro derivatives 6a – 6e in the binding affinity at the human A3 AR but showed less selectivity versus the other subtypes of ARs. In the 3-halobenzyl series, the order of binding affinity for 2-H analogues was as follows: Cl > I > Br > F, indicating that the size of halogen alone does not determine the binding affinity at the human A3 AR. It is interesting to note that 2-H derivatives are less lipophilic than the corresponding 2-Cl derivatives, conferring more water solubility on the molecules for further biological evaluation. For example, the cLogP values of corresponding structures 6c and 7c are 1.84 and 1.12, respectively. In order to determine a stereochemical preference, the binding affinities of D-series were compared with those of L-series. As shown in Table 1, L-type nucleosides, 7f and 7g were totally devoid of binding affinities at all subtypes of ARs, indicating that the D-series induced optimal interaction with all subtypes of ARs.

Table 1.

Binding affinities of known A3 AR agonists, 1 – 4 and antagonist 5, and truncated 4′-thioadenosine derivatives 6a – 6e and 7a – 7g at three subtypes of ARs.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Affinity, Ki, nM ± SEM (or % Inhibition at 10−5M)a,b | |||

| hA1 | hA2A | rA3 | hA3c | |

| 1(IB-MECA) | 51 | 2900 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| 2 (Cl-IB-MECA) | 222 ± 22 | 5360 ± 2470 | 0.33 | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| 3 (thio-IB-MECA) | 17.3 | ND | 1.86 ± 0.36 | 0.25 ± 0.06 |

| 4 (thio-Cl-IB-MECA) | 193 ± 46 | 223 ± 36 | 0.82 ± 0.27 | 0.38 ± 0.07 |

| 5 | 6220 ± 640 | > 10,000 | 321 ± 74 | 15.5 ± 3.1 |

| 6a (R1 = Cl, R2 = methyl) | 55.4 ± 1.8 | 45.0 ± 1.4 | 658 ± 160 | 3.69 ± 0.25 |

| 6b (R1 = Cl, R2 = 3-fluorobenzyl) | (20%) | (48%) | 36.2 ± 10.7 | 7.4 ± 1.3 |

| 6c (R1 = Cl, R2 = 3-chlorobenzyl) | (38%) | (18%) | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 1.66 ± 0.90 |

| 6d (R1 = Cl, R2 = 3-bromobenzyl) | (34%) | (18%) | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 8.99 ± 5.17 |

| 6ed (R1 = Cl, R2 = 3-iodobenzyl) | 2490 ± 940 | 341 ± 75 | 3.89 ± 1.15 | 4.16 ± 0.50 |

| 7a (R1 = H, R2 = methyl) | 1070 ± 180 | (22 ± 5%) | (28 ± 10%) | 4.8 ±1.7 |

| 7b (R1 = H, R2 = 3-fluorobenzyl) | 1430 ± 420 | 1260 ± 330 | 98 ± 28 | 7.3 ± 0.6 |

| 7c (R1 = H, R2 = 3-chlorobenzyl) | 860 ± 210 | 440 ± 110 | 17 ± 5 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| 7d (R1 = H, R2 = 3-bromobenzyl) | 790 ± 190 | 420 ± 32 | 6.3 ± 1.3 | 6.8 ± 3.4 |

| 7e (R1 = H, R2 = 3-iodobenzyl) | 530 ± 97 | 45.0 ± 1.4 | 658 ± 160 | 3.69 ± 0.25 |

| 7f (R1 = Cl, R2 = 3-bromobenzyl) | (6.1%) | (45.7%) | ND | (12.6%) |

| 7g (R1 = Cl, R2 = 3-iodobenzyl) | (−8.0%) | (−0.95%) | ND | (18.4%) |

ND: Not determined.

All binding experiments were performed using adherent mammalian cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding the appropriate human AR (A1 AR and A3 AR in CHO cells and A2A AR in HEK-293 cells) or the rat A3 AR (CHO cells). Binding was carried out using 1 nM [3H]CCPA, 10 nM [3H]CGS-21680, or 0.5 nM [125I]I-AB-MECA as radioligands for A1, A2A, and A3 ARs, respectively. Values are expressed as mean ± sem, n = 3–4 (outliers eliminated), and normalized against a non-specific binder, 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA, 10 μM). Data for compounds 6a – 6e at the human ARs and compound 6e at the rat A3 AR were reported in ref. 1.

When a value expressed as a percentage refers to percent inhibition of specific radioligand binding at 10 μM, with nonspecific binding defined using 10 μM NECA.

A functional assay was also carried out at this subtype: percent inhibition at 10 μM forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP production in CHO cells expressing the human A3 AR, as a mean percentage of the response of the full agonist 3 (n = 1 – 3). None of the analogues 5 – 7 activated the hA3AR (>10% of full agonist effect) by this criterion.

Compound 6e at 10 μM displayed <10% of the full stimulation of cyclic AMP production, in comparison to 10 μM NECA; no inhibition of the stimulatory effect of 150 nM NECA in CHO cells expressing human A2B AR (ref. 1).

In order to determine if all final nucleosides show species-independent binding affinity at the A3 AR, their binding affinity at the rat A3 AR expressed in CHO cells was also measured (Table 1). As expected, most of compounds exhibited species-independent binding affinity, indicating that they are suitable for evaluation in small animal models or for further drug development Among the 2-H nucleoside analogues tested, a N6-(3-bromobenzyl) derivative 7d exhibited the most potent binding affinity at the rat A3 AR (Ki = 6.3 ± 1.3 nM) followed by N6-(3-chlorobenzyl) derivative 7c, N6-(3-iodobenzyl) derivative 7e, and N6-(3-fluorobenzyl) derivative 7b. N6-Methyl derivative 7a was totally devoid of A3AR binding affinity in this species. In the 2-Cl-N6-substituted adenosine series, the binding affinity was in the following order: I > Br ≈ Cl > F > Me. The 2-Cl derivatives generally showed more potent and species-indepndent binding affinity than the corresponding 2-H analogues. Compound 6e exhibited the highest binding affinity at the rat A3 AR (Ki = 3.89 ± 1.15 nM) among all compounds tested and was inactive as agonist or antagonist in a cyclic AMP functional assay16,17 at the hA2B AR. It is interesting to note that N6-methyl derivatives 6a and 7a showing high binding affinities (Ki = 3.69 ± 0.25 nM and 4.8 ± 1.7 nM, respectively) at the human A3 AR lost their binding affinities at the rat A3 AR, indicating that there must be a larger N6 substituent for species-independent binding affinity at the A3 AR.18,19

In a functional assay, percent inhibition at 10 μM forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP production in CHO cells expressing the human A3 AR was measured as a mean percentage of the response of the full agonist 3 (n = 1 – 3). None of the analogues 6 and 7 activated the human A3 AR (> 10% of full agonist effect) by this criterion.

Conclusion

We have established structure-activity relationships of novel truncated D- and L-4′-thionucleoside analogues as potent species-independent A3 AR antagonists. The glycosyl donors 8 and 12 were efficiently synthesized from D-mannose and D-gulonic γ-lactone, respectively, using ring closure of dimesylate with sodium sulfide and one step conversion of the diol into the acetate with lead tetraacetate as key steps. Among the novel 4′-truncated 2-H nucleosides tested, D-N6-(3-halobenzyl) derivatives 7b – 7e exhibited high binding affinities at the human A3 AR as well as at the rat A3 AR with very low binding affinities at the human A1 and A2A ARs and a N6-(3-chlorobenzyl) derivative 7c was the most potent at the human A3 AR, but at the rat A3 AR 3-bromobenzyl derivative 7d was the most potent. Among both 2-H and 2-Cl analogues tested, 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl) derivative 6e was found to exhibit the most potent binding affinity at the rat A3 AR. Since this class of potent nucleoside human A3 AR antagonists showed species-independence in interaction at this AR subtype, they are regarded as good candidates for efficacy evaluation in small animal models and for further drug development.

Experimental Section

General methods

Melting points are uncorrected. 1H NMR (400 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz) spectra were measured in CDCl3, CD3OD or DMSO-d6, and chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (δ) downfield from tetramethylsilane as internal standard. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh). Anhydrous solvents were purified by the standard procedures. cLogP values were calculated using ChemDrawUltra, version 11.0 (CambridgeSoft).

Synthesis

6-Chloro-9-((3aR,4R,6aS)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrothieno[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)-9H-purine (9)

6-Chloropurine (3.91 g, 25.3 mmol), ammonium sulfate (84 mg, 0.63 mmol) and HMDS (50 mL) were refluxed under inert and dry conditions overnight. The solution was evaporated under high vacuum. The resulting solid was re-dissolved in 1,2-dichloroethane (20 mL) cooled in ice. The solution of 81 (2.76 g, 12.6 mmol) in 1,2-dichloroethane (20 mL) was added to this mixture dropwise. TMSOTf (4.6 mL, 25.3 mmol) was added dropwise to the mixture. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min, at rt for 1 h, and then heated at 80 °C for 2 h. The mixture was cooled, diluted with CH2Cl2, and washed with saturated NaHCO3 solution. The organic layer was dried with anhydrous MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The yellowish syrup was subjected to a flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH = 50:1) to give 9 (3.59 g, 90%) as a foam: [α]23.6D-157.63 (c 0.144, DMSO); FAB-MS m/z 313 [M+H]+; UV (MeOH) λmax 265.0 nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.67 (s, 1 H), 8.23 (s, 1 H), 5.88 (s, 1 H), 5.25-5.19 (m, 1 H), 3.69 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 13.2 Hz), 3.18 (d, 1 H, J = 12.8 Hz), 1.51 (s, 3 H), 1.28 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 152.0, 151.4, 151.1, 144.3, 132.6, 111.9, 89.6, 84.3, 70.3, 40.8, 26.4, 24.6. Anal. (C12H13ClN4O2S) C, H, N, S.

(2R,3R,4S)-2-(6-Chloro-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (10)

2 N Hydrochloric acid (12 mL) was added to a solution of 9 (2.59 g, 8.28 mmol) in THF (20 mL), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The mixture was neutralized with 1 N NaOH solution, and then the volatiles were carefully evaporated under reduced pressure. The mixture was subjected to a flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH = 20:1) to give 10 (1.79 g, 79%) as a white solid: [α]23.5D-109.14 (c 0.164, DMSO); FAB-MS m/z 273 [M+H]+; mp 192.3–192.8 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 264.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.02 (s, 1 H), 8.81 (s, 1 H), 6.02 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.62 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.43 (d, 1 H, J = 4.1 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.74-4.70 (m, 1 H), 4.40-4.36 (m, 1 H), 3.47 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 11.2 Hz), 2.83 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.8, 11.2 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) 152.1, 151.6, 149.2, 146.6, 131.3, 78.6, 72.1, 62.4, 34.7. Anal. (C9H9ClN4O2S) C, H, N, S.

General procedure for the synthesis of 7a – 7e

To a solution of 10 in EtOH (5 mL) was added appropriate amine (1.5 equiv) at room temperature and the mixture was stirred at rt for a time period ranging from 2 h to 3 d and evaporated. The residue was purified by a flash silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH = 20:1) to give 7a – 7e.

(2R,3R,4S)-Tetrahydro-2-(6-(methylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl)thiophene-3,4-diol (7a)

83% yield; [α]22.8D-175.60 (c 0.123, DMSO); FAB-MS m/z 268 [M+H]+; mp 223.9–224.8 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 266.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.40 (s, 1 H), 8.23 (s, 1 H), 7.72 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 5.89 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.51 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5. 32 (d, 1 H, J = 4.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.70-4.64 (m, 1 H), 4.37-4.33 (m, 1 H), 3.40 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 10.8 Hz), 2.95 (s, 3 H), 2.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 10.8 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 154.9, 152.5, 148.8, 139.5, 119.5, 78.3, 72.2, 61.5, 34.6, 27.0. Anal. (C10H13N5O2S) C, H, N, S.

(2R,3R,4S)-2-(6-(3-Fluorobenzylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl)tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (7b)

82% yield; [α]23.7D-141.22 (c 0.114, DMSO); FAB-MS m/z 362 [M+H]+; mp 180.5–180.7 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 273.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.45 (s, 1 H), 8.43 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 8.21 (s, 1 H), 7.36-7.30 (m, 1 H), 7.18-7.11 (m, 2 H), 7.03 (dt, 1 H, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 5.90 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.53 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.35 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.70-4.66 (m, 2 H), 4.36-4.33 (m, 1 H), 3.41 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 10.8 Hz), 3.17 (d, 1 H, J = 5.2 Hz), 2.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.8, 10.8 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 163.4, 160.9, 152.4, 143.2, 140.0, 130.2, 130.1, 123.1, 123.1, 113.8, 113.6, 113.4, 113.2, 78.3, 72.2, 61.6, 48.6, 34.4. Anal. (C16H16FN5O2S) C, H, N, S.

(2R,3R,4S)-2-(6-(3-Chlorobenzylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (7c)

85% yield; [α]23.9D-162.5 (c 0.096, DMSO); FAB-MS m/z 378 [M+H]+; mp 165.0–165.3 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 274.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.46 (s, 1 H), 8.44 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 8.22 (s, 1 H), 7.39-7.24 (m, 4 H), 5.90 (d, 1 H, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.53 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.35 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.71-4.67 (m, 2 H), 4.38-4.33 (m, 1 H), 3.47-3.31 (m, 2 H), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 10.8 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 154.3, 152.4, 142.8, 140.0, 132.8, 130.1, 126.9, 126.6, 125.8, 78.3, 72.2, 61.6, 56.0, 34.4. Anal. (C16H16ClN5O2S) C, H, N, S.

(2R,3R,4S)-2-(6-(3-Bromobenzylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (7d)

71% yield; [α]23.7D-100.71 (c 0.139, DMSO); FAB-MS m/z 422 [M]+; mp 183.0–184.0 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 270.0 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.46 (s, 1 H), 8.43 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 8.21 (s, 1 H), 7.53 (s, 1H) 7.42-7.24 (m, 3 H), 5.90 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.53 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5.35 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.71-4.66 (m, 2 H), 4.37-4.34 (m, 1 H), 3.41 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.0, 10.8 Hz), 3.06 (q, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz). 2.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.8, 10.8 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 154.2, 152.4, 143.0, 140.0, 130.4, 129.8, 129.4, 126.2, 121.5, 78.3, 72.2, 61.6, 45.5, 34.5. Anal. (C16H16BrN5O2S) C, H, N, S.

(2R,3R,4S)-2-(6-(3-Iodobenzylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol (7e)

88% yield; [α]23.8D-97.08 (c 0.137, DMSO); FAB-MS m/z 370 [M+H]+; mp 198.8–199.8 °C; UV (MeOH) λmax 271.5 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.45 (s, 1 H), 8.43 (br s, 1 H, D2O exchangeable), 8.21 (s, 1 H), 7.72 (s, 1 H), 7.56 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.35 (d, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.10 (merged dd, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz), 5.90 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.53 (d, 1 H, J = 6.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 5. 35 (d, 1 H, J = 4.4 Hz, D2O exchangeable), 4.71-4.66 (m, 2 H), 4.37-4.34 (m, 1 H), 3.41 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.8, 10.8 Hz), 3.15 (d, 1 H, J = 5.2 Hz), 2.79 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.8, 10.8 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 154.2, 152.4, 149.2, 142.9, 140.0, 137.0, 135.7, 135.3, 130.4, 126.6, 94.7, 78.3, 72.2, 61.6, 42.2, 34.4. Anal. (C16H16IN5O2S) C, H, N, S.

L-4-Thiosugar acetate 12 was synthesized from D-gulonic acid γ-lactone according to a similar procedure1,13 used for the preparation of 8 (Scheme 1). Then L-4-thiosugar acetate 12 was converted to 13 according to a similar procedure used for the preparation of 9. The final L-4′-thio nucleosides 7f and 7g were synthesized from 12 according to the described general procedure for the synthesis of 7a – 7e.

The 1H, 13C NMR, UV, and mp data of L-series compounds were the same as for the D-series of compounds as described above, except that the specific optical rotations were in the opposite direction. Yields of the L-series compounds were comparable with those of the D-series of compounds.

Binding assays1,6

Human A1 and A2A ARs

For binding to human A1 AR, [3H]CCPA (1 nM) was incubated with membranes (40 μg/tube) from CHO cells stably expressing human A1 ARs at 25 °C for 60 min in 50 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4; MgCl2, 10 mM) in a total assay volume of 200 μL. Nonspecific binding was determined using 10 μM of NECA. For human A2A AR binding, membranes (20 μg/tube) from HEK-293 cells stably expressing human A2A ARs were incubated with 15 nM [3H]CGS21680 at 25 °C for 60 min in 200 μL 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, containing 10 mM MgCl2. NECA (10 μM) was used to define nonspecific binding. Reaction was terminated by filtration with GF/B filters.

Human and Rat A3 ARs

For competitive binding assay, each tube contained 100 μL of membrane suspension (from CHO cells stably expressing the human or rat A3 AR, 20 μg protein), 50 μL of [125I]I-AB-MECA (0.5 nM), and 50 μL of increasing concentrations of the nucleoside derivative in Tris·HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) containing 10 mM MgCl2. Nonspecific binding was determined using 10 μM of NECA in the buffer. The mixtures were incubated at 25 °C for 60 min. Binding reactions were terminated by filtration through Whatman GF/B filters under reduced pressure using a MT-24 cell harvester (Brandell, Gaithersburgh, MD, USA). Filters were washed three times with 9 mL ice-cold buffer. Radioactivity was determined in a Beckman 5500B γ-counter.

For binding at all three subtypes, Ki values are expressed as mean ± sem, n = 3–4 (outliers eliminated), and normalized against a non-specific binder, 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA, 10 μM). Alternately, for weak binding a percent inhibition of specific radioligand binding at 10 μM, relative to inhibition by 10 μM NECA assigned as 100%, is given.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2008-E00304) and the Intramural Research Program of NIDDK, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AR

adenosine receptor

- CCPA

2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- IB-MECA

N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine

- Cl-IB-MECA

2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine

- I-AB-MECA

2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl-ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- NECA

5′-Nethylcarboxamidoadenosine

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Elemental analyses data for all unknown compounds and pharmacological methods. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.The preliminary accounts of this work have been published in Jeong LS, Choe SA, Gunaga P, Kim HO, Lee HW, Lee SK, Tosh DK, Patel A, Palaniappan KK, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Moon HR. Discovery of a new nucleoside template for human A3 adenosine receptor ligands: D-4′-thioadenosine derivatives without 4′-hydroxymethyl group as highly potent and selective antagonists. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3159–3162. doi: 10.1021/jm070259t.

- 2.Olah ME, Stiles GL. The role of receptor structure in determining adenosine receptor activity. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;85:55–75. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nature Rev Drug Disc. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Klotz K-N. Adenosine receptors and their ligands. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:382–391. doi: 10.1007/s002100000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Baraldi PG, Cacciari B, Romagnoli R, Merighi S, Varani K, Borea PA, Spalluto GA. 3 adenosine receptor ligands: history and perspectives. Med Res Rev. 2000;20:103–128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(200003)20:2<103::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishman P, Madi L, Bar-Yehuda S, Barer F, Del Valle L, Khalili K. Evidence for involvement of Wnt signaling pathway in IB-MECA mediated suppression of melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:4060–4064. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HO, Ji X-d, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5′-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Jeong LS, Jin DZ, Kim HO, Shin DH, Moon HR, Gunaga P, Chun MW, Kim YC, Melman N, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. N6-Substituted D-4′-thioadenosine-5′-methyluronamides: potent and selective agonists at the human A3 adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3775–3777. doi: 10.1021/jm034098e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeong LS, Lee HW, Jacobson KA, Kim HO, Shin DH, Lee JA, Gao Z-G, Lu C, Duong HT, Gunaga P, Lee SK, Jin DZ, Chun MW, Moon HR. Structure-activity relationships of 2-chloro-N6-substituted-4′-thioadenosine-5′-uronamides as highly potent and selective agonists at the human A3 adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2006;49:273–281. doi: 10.1021/jm050595e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jeong LS, Lee HW, Kim HO, Jung JY, Gao Z-G, Duong HT, Rao S, Jacobson KA, Shin DH, Lee JA, Gunaga P, Lee SK, Jin DZ, Chun MW. Design, synthesis, and biological activity of N6-substituted-4′-thioadenosines at the human A3 adenosine receptor. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:4718–4730. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Lee EJ, Min HY, Chung HJ, Park EJ, Shin DH, Jeong LS, Lee SK. A novel adenosine analog, thio-Cl-IB-MECA, induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chung H, Jung J-Y, Cho S-D, Hong K-A, Kim H-J, Shin D-H, Kim H, Kim HO, Lee HW, Jeong LS, Gong K. The antitumor effect of LJ-529: a novel agonist to A3 adenosine receptor, in both estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen-negative human breast cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:685–692. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Jacobson KA, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Ji Xd, Melman N, Bellamkonda K, Meshulam Y, Stiles GL, Kim HO. Structure-activity relationships of 9-alkyladenine and ribose-modified adenosine derivatives at rat A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1995;38:1720–1735. doi: 10.1021/jm00010a017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Volpini R, Costanzi S, Lambertucci C, Vittori S, Kliotz K-N, Lorenzen A, Cristalli G. Introduction of alkynyl chains on C-8 of adenosine led to very selective antagonists of the A3 adenosine receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:1931–1934. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gao Z-G, Kim S-K, Biadatti T, Chen W, Lee K, Barak D, Kim SG, Johnson CR, Jacobson KA. Structural determinants of A3 adenosine receptor activation: Nucleoside ligands at the agonist/antagonist boundary. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4471, 4484. doi: 10.1021/jm020211+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baraldi PG, Tabrizi MA, Romagnoli R, Fruttarolo F, Merighi S, Varani K, Gessi S, Borea PA. Pyrazolo[4,3-e]1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine ligands, new tools to characterize A3 adenosine receptors in human tumor cell lines. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1319–1329. doi: 10.2174/0929867054020963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao ZG, Blaustein J, Gross AS, Melman N, Jacobson KA. N6-Substituted adenosine derivatives: Selectivity, efficacy, and species differences at A3 adenosine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1675–1684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SK, Gao ZG, Jeong LS, Jacobson KA. Docking studies of agonists and antagonists suggest an activation pathway of the A3 adenosine receptor. J Mol Graph Model. 2006;25:562–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Gao ZG, Joshi BV, Klutz A, Kim SK, Lee HW, Kim HO, Jeong LS, Jacobson KA. Conversion of A3 adenosine receptor agonists into selective antagonists by modification of the 5′-ribofuran-uronamide moiety. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeong LS, Lee HW, Kim HO, Tosh DK, Pal P, Choi WJ, Gao Z-G, Patel AR, Williams W, Jacobson KA, Kim H-D. Structure-activity relationships of 2-chloro-N6-substituted-4′-thioadenosine-5′-N,N-dialkyluronamides as the human A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1612–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunaga P, Kim HO, Lee HW, Toshi DK, Ryu JS, Choi S, Jeong LS. Stereoselective functionalization of the 1′-position of 4′-thionucleosides. Org Lett. 2006;8:4267–4270. doi: 10.1021/ol061548z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Klotz KN, Hessling J, Hegler J, Owman C, Kull B, Fredholm BB, Lohse MJ. Comparative pharmacology of human adenosine receptor subtypes – characterization of stably transfected receptors in CHO cells. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357:1–9. doi: 10.1007/pl00005131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gao ZG, Mamedova L, Chen P, Jacobson KA. 2-Substituted adenosine derivatives: Affinity and efficacy at four subtypes of human adenosine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1985–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YC, Ji X-d, Melman N, Linden J, Jacobson KA. Anilide derivatives of an 8-phenylxanthine carboxylic congener are highly potent and selective antagonists at human A2B adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 2000;43:1165–1172. doi: 10.1021/jm990421v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordstedt C, Fredholm BB. A modification of a protein-binding method for rapid quantification of cAMP in cell-culture supernatants and body fluid. Anal Biochem. 1990;189:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90113-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Post SR, Ostrom RS, Insel PA. Biochemical methods for detection and measurement of cyclic AMP and adenylyl cyclase activity. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;126:363–374. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-684-3:363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohno M, Gao ZG, Van Rompaey P, Tchilibon S, Kim SK, Harris BA, Gross AS, Duong HT, Van Calenbergh S, Jacobson KA. Modulation of adenosine receptor affinity and intrinsic efficacy in adenine nucleosides substituted at the 2-position. J Med Chem. 2004;12:2995–3007. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melman A, Gao ZG, Kumar D, Wan TC, Gizewski E, Auchamapach JA, Jacobson KA. Design of (N)-methanocarba adenosine 5′-uronamides as species-independent A3 receptor-selective agonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:2813–2819. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.