Abstract

Objective

The majority of women referred for colposcopy are not diagnosed with CIN2+ but, nonetheless, are typically asked to return much sooner than their next routine screening interval in 3-5 years. An important question is how many subsequent negative Pap results, or negative Pap and HPV cotest results, are needed prior to returning to an extended retesting interval.

Methods

We estimated 5-year risks of CIN2+ for 3 follow-up management strategies after colposcopy (Pap-alone, HPV-alone and cotesting) for 20,319 women aged 25 and older screened from 2003-2010 at Kaiser Permanente Northern California who were referred for colposcopy but for whom CIN2+ was not initially diagnosed (i.e., “Women with CIN1/negative colposcopy”).

Results

Screening results immediately antecedent to CIN1/negative colposcopy influenced subsequent 5-year CIN2+ risk: women with an antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL Pap had a lower risk (10%) than those with antecedent ASC-H (16%, p<0.0001) or HSIL+ (24%, p<0.0001). For women with an antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL, a single negative cotest approximately 1 year post-colposcopy predicted lower subsequent 5-year risk of CIN2+ (1.1%) than 2 sequential negative HPV tests (1.8%, p=0.3) or 2 sequential negative Pap results (4.0%, p<0.0001). For those with an antecedent ASC-H or HSIL+ Pap, 1 negative cotest after 1 year predicted lower subsequent 5-year risk of CIN2+ (2.2%) than 1 negative HPV test (4.4%, p=0.4) or 1 negative Pap (7.0%, p=0.06); insufficient data existed to calculate risk after sequential negative cotests for women with high grade antecedent cytology.

Conclusions

After CIN1/negative colposcopy followed by negative post-colposcopy tests, women did not achieve sufficiently low CIN2+ risk to return to 5-year routine screening. For women with antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL, a single negative post-colposcopy cotest reduced risk to a level consistent with a 3-year return. For women with antecedent ASC-H or HSIL+, no single negative test result sufficed to reduce risk to a level consistent with a 3-year return.

Precis

For women with CIN1/negative colposcopy and antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL, a single negative post-colposcopy cotest reduced risk to a level consistent with a 3-year return.

Keywords: Human Papillomavirus (HPV), cancer prevention, Pap, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2), colposcopy

Introduction

In the US, few women referred to colposcopy are diagnosed immediately with histologically confirmed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2) or worse (CIN2+) that requires treatment. This is because many women are referred to colposcopy for LSIL or HPV-positive/ASC-US, rather than higher-risk screening results, such as ASC-H or HSIL. Recent changes in screening guidelines (1, 2) that incorporate cotesting recommend that women with persistent HPV-positive/Pap-negative results also should be referred to colposcopy, further increasing the number of colposcopic examinations that will result in CIN1 or negative colposcopic diagnoses (benign colposcopic appearance, or a negative or CIN1 biopsy).

The 2006 management guidelines recommend repeat testing at 6 or 12 month intervals (3) for women with a CIN1/negative colposcopy diagnosis. While laborious, such heightened surveillance is warranted because, compared with the general population, these women remain at elevated risk of being diagnosed with subsequent CIN2+ (4-7). However, most women with a normal colposcopic impression or normal/CIN1 histology will never develop CIN2+ (6) and therefore should return to routine screening at some point. Continued intensive surveillance of these women can often find minor abnormalities that would naturally resolve without treatment. But, since the discovery of minor abnormalities misplaces women into a “higher risk” category that justifies even more surveillance, it is increasingly difficult to ever return them to a routine screening schedule.

Consequently, the resultant question in patient management is to define a sufficient number of negative follow-up tests that will provide assurance that a woman is safe for return to routine screening or, at least, to extended retesting intervals. The 2006 ASCCP management guidelines for women with a CIN1 or negative colposcopy provide recommendations for return to routine screening by the referring (i.e., “antecedent”) Pap result, because the risk of an undetected or incipient CIN2+ is expected to be greater in women with an antecedent HSIL or greater Pap result than in women with an ASCUS or LSIL Pap (3). Under the current guidelines, women with CIN1 preceded by HSIL or greater Pap results can return to routine cytologic screening at 3 years, after 2 negative colposcopy and Pap results. Women with CIN1 preceded by ASC-US, ASC-H or LSIL can return to routine cytologic screening after either 2 Pap-negative tests at 6-month intervals or 1 HPV-negative test at 1 year. (Of note, ASC-H was combined with ASC-US and LSIL in the 2006 recommendations.) However, the 2006 recommendations were largely based upon expert opinion because only limited data were available (6). Furthermore, the 2006 recommendations did not provide guidance on the use of cotesting for follow-up post-colposcopy.

Data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), a large integrated health system that routinely performs cotesting for both screening and some aspects of follow-up management, are now available to estimate more accurately the risks of subsequent CIN2+ in women following a CIN1 or negative colposcopy. In this manuscript, we evaluate the risks of CIN2+ in post-colposcopic management of women without initial evidence of CIN2, with consideration of their antecedent Pap and follow-up Pap and cotest results.

Methods

The design of our cohort study from KPNC has been described previously (8); in this report we enlarged the dataset from women age 30-64 to include all women age 25 and older, screened from 2003 to 2010, in order to increase the numbers of women with post-colposcopy information. Data on histologic outcomes were collected on all women through December 31, 2010. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved use of the data, and the National Institutes of Health Office of Human Subjects Research deemed this study exempt from IRB review. The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) develops Clinical Practice Guidelines for cervical cancer screening and management of abnormal tests in partnership with the KP National Guideline Program, Care Management Institute, to support clinical decisions of their providers. According to guidelines, women with HPV-positive/ASC-US, or with LSIL or worse Pap results, should undergo colposcopy. Per KPNC guidelines, at least 1 biopsy is taken at the great majority of colposcopy examinations to improve the sensitivity. Therefore, histological results are available for most women referred for colposcopy. For women with a CIN1/negative colposcopy, KPNC guidelines are virtually identical to those of ASCCP; in practice at KPNC cotesting, rather than Pap or HPV tests alone, is the predominant mode of screening and follow-up testing. When risk was calculated for a cytology result without regard to HPV testing, or vice versa, we refer to those risks as “Pap-alone” or “HPV-alone”.

Pap tests were performed at KPNC regional and facility labs. Conventional Pap slides were manually reviewed following processing by the BD FocalPoint Slide Profiler (BD Diagnostics, Burlington, NC, USA) primary screening and directed quality control system, in accordance with FDA-approved protocols. Starting in 2009, KPNC transitioned to liquid-based Pap testing using BD SurePath (BD Diagnostics, Burlington, NC, USA). Conventional or liquid-based Pap tests are reported according to the 2001 Bethesda System(9). HPV tests were performed only in the KPNC regional lab. Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2; Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) was used to test for high-risk HPV types according to manufacturer’s instructions.

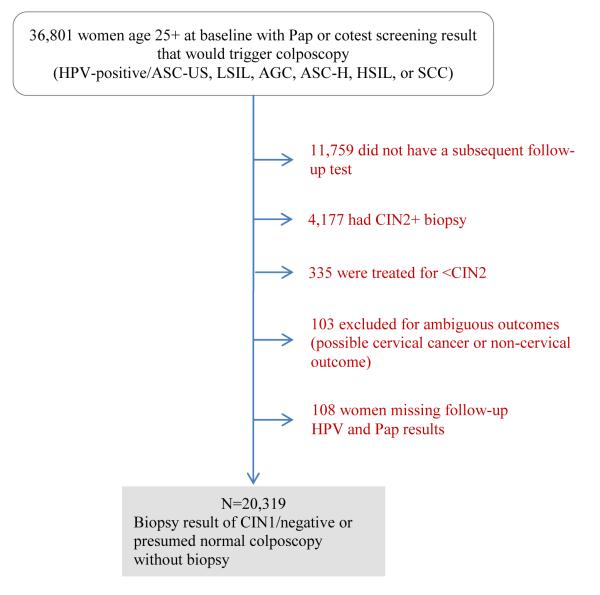

Figure 1 provides a description of the study population. This analysis was limited to women with a baseline Pap and/or cotest screening result (called “antecedent screen”) that would trigger referral for colposcopy: HPV-positive/ASC-US, LSIL, AGC, ASC-H, HSIL, or SCC. We then excluded from the analysis women who had a CIN2+ biopsy result at the colposcopy triggered by the screening results. Because we wished to define risk after follow-up testing, we also omitted women without further follow-up testing (either Pap-alone or cotests). Finally, women were excluded in the rare occasion that they were treated after the antecedent screen but before a biopsy result.

Figure 1.

Diagram of women with CIN1/negative colposcopy

Therefore, the women who remained in this analysis had (1) a biopsy result of CIN1 or normal/metaplasia, (2) a normal colposcopy without biopsy or (3) no colposcopy between the antecedent abnormal screen that would trigger referral to colposcopy and the follow-up Pap or cotest. We are unable to distinguish the women in groups (2) and (3) because this analysis is based upon histology records. We therefore chose to include them because a chart review of KPNC colposcopy records showed that the majority of women fell into group (2), having had colposcopy before their subsequent follow-up test.

By definition, women in this cohort were not diagnosed with CIN2+ before follow-up testing. Therefore, the cumulative risk of CIN2+, CIN3+, or cervical cancer was calculated as the sum of risk at the first follow-up test after the antecedent screen (plotted at time zero on each figure) and the incidence following the first follow-up test (8). The results were stratified by women’s antecedent screening results.

Although the majority of women underwent cotesting, we disaggregated results and then compared 3 management strategies to follow-up women post-colposcopy: Pap-alone, HPV-alone, and cotesting. All Pap and HPV test results from up to 2 consecutive follow-up tests were used to identify women testing negative at follow-up under a given strategy (e.g., all Pap results were included in the Pap-alone strategy, regardless if the Pap test was part of a cotest or not). In an ancillary analysis (data not shown), we verified that the risks calculated based on this Pap-alone definition were similar to risks from a Pap-alone strategy with no HPV test. The cumulative 5-year CIN2+ risks were calculated for women who had negative follow-up test results for each of the 3 management strategies. The 5-year CIN2+ risks are calculated starting from the date of the last negative follow-up test (i.e., the risk after the 1st follow-up test for 1 negative Pap result, the risk after the 2nd follow-up test for 2 consecutively negative Pap results).

In general, we focused on risk of CIN2+ for this analysis because we had too few CIN3+ events to estimate reliably the CIN3+ risks. When zero incident CIN2+ events occurred, no exact p-value or confidence interval could be calculated, so we calculated conservative confidence intervals by calculating the right-endpoint of the confidence interval with 1 CIN2+ event and inverting this interval to obtain p-values when needed.

Results

We identified 20,319 women with a biopsy result of CIN1/negative or presumed normal colposcopy exam and subsequent follow-up tests (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the data used in the following analyses, specifically the distribution, by antecedent Pap or cotest result, of the worst histologic findings through 2010, for all women with CIN1/negative colposcopy. Antecedent screening results predicted subsequent risk. Most (84%) of the antecedent Pap/cotest results were “lesser abnormalities” (HPV-positive/ASC-US, LSIL) but a minority (38%) of the 34 cancers occurred in these women. The proportions of CIN2+ diagnoses during follow-up that were CIN3/AIS or cancer (CIN3+) also differed by antecedent screening result: the proportions of CIN3+ diagnoses were higher for women with an antecedent ASC-H or HSIL+ Pap (47.7% CIN3/AIS and 6.5% cancer) than for women with an antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US cotest or LSIL Pap (CIN3/AIS: 34.7%, p<0.0001; Cancer: 1.4%, p<0.0001). The proportion of cancer following an antecedent AGC Pap (14.0%) was greater than that following ASC-H or HSIL+ (6.5%, p=0.1) or lesser abnormalities, (1.4%, p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Distribution of worst histologic diagnosis among women with CIN1/negative colposcopy aged 25 and older, given antecedent Pap or cotest result that preceded colposcopy

| Total |

Worst histologic diagnosis during follow-up after CIN1/negative colposcopy |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent Pap and HPV test result | n | <CIN1, n |

CIN1, n |

CIN2, n |

CIN3, n |

AIS, n |

Total CIN3 or AIS, n |

Squamous carcinoma, n |

Adeno- carcinoma, n |

Total cancers, n |

| Total | 20,319 | 10,381 | 8,701 | 737 | 434 | 31 | 466 | 14 | 14 | 34 |

| HPV-positive/ASC-US | 9,936 | 4,901 | 4,440 | 376 | 199 | 11 | 210 | 2 | 5 | 9 |

| LSIL | 7,161 | 3,335 | 3,448 | 246 | 125 | 2 | 128 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| AGC | 1,484 | 1,202 | 232 | 17 | 18 | 8 | 26 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| ASC-H | 1,189 | 680 | 393 | 57 | 46 | 5 | 51 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| HSIL+ | 549 | 263 | 188 | 41 | 46 | 5 | 51 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

Note: Total cancers include not only squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma but also adenosquamous carcinoma, and cervical cancer of unknown histology or histology unrelated to HPV infection. The category “Total CIN3 or AIS” also includes 1 woman with a diagnosis that did not differentiate between CIN3 and AIS. “HSIL+” includes HSIL and the few women with SCC and AIS Pap results.

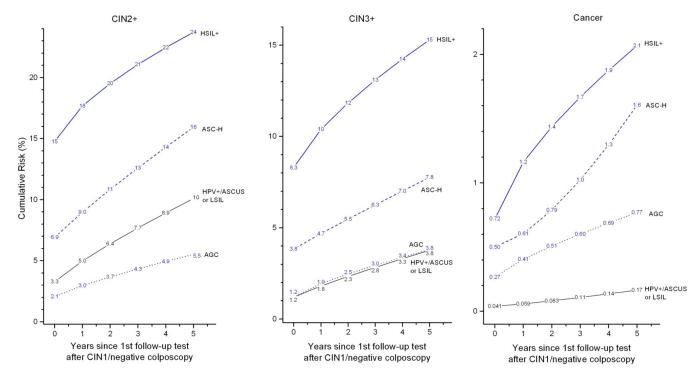

Figure 2 shows the overall risks of subsequent CIN2+, CIN3+, and cancer following a CIN1/negative colposcopy, stratified by antecedent Pap/cotest. Women with a CIN1/negative colposcopy had substantially reduced CIN2+ risks for each Pap/cotest result relative to the risks prior to colposcopy (8). However, women with high-grade antecedent Pap results continued to have elevated 5-year risks for CIN2+ (24% for women with an antecedent HSIL or worse, compared with 10% for women with HPV+/ASC-US or LSIL). Moreover, women with an antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL had a 0.17% 5-year cancer risk, considerably lower than rates for women with high-grade screening abnormalities (AGC:0.77%, p=0.006; ASC-H:1.6%, p=0.0002; HSIL+: 2.1%, p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Cumulative risk of CIN2+ (Left Panel), CIN3+ (Middle Panel), and cancer (Right Panel) following CIN1/negative colposcopy given antecedent HSIL+, ASC-H, AGC, and HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL, among women aged 25 and older. Note that the y-axes have different scales for different panels.

Table 2 shows the actual number of women who had a negative Pap, HPV or cotest result at subsequent follow-up tests. Among women with antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL, 5939 were followed with cotesting, 5450 were followed with Pap alone (11389-5939), and 1031 were followed with HPV alone (6970-5939). Among women with antecedent AGC/ASC-H/HSIL+, 1501 were followed with cotesting, 683 were followed with Pap alone, and 248 were followed with HPV alone.

Table 2.

Distribution of worst histologic diagnosis following CIN1/negative colposcopy for women age 25 and older, given antecedent Pap or cotest result and subsequent negative follow-up test results

| Total |

Worst histologic diagnosis during follow-up after CIN1/negative colposcopy |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent Pap and HPV test result and follow-up Pap result |

n | <CIN1, n |

CIN1, n |

CIN2, n |

CIN3, n |

AIS, n |

Total CIN3 or AIS, n |

Squamous carcinoma, n |

Adeno- carcinoma, n |

Total cancers, n |

| Antecedent HPV+/ASCUS or LSIL | ||||||||||

| One negative Pap | 11,389 | 6,198 | 4,953 | 157 | 69 | 5 | 74 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Two negative Paps | 5,019 | 2,698 | 2,260 | 37 | 19 | 2 | 21 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| One negative HPV test | 6,970 | 3,949 | 2,972 | 32 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Two negative HPV tests | 2,649 | 1,510 | 1,129 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| One negative cotest | 5,939 | 3,408 | 2,512 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Two negative cotests | 1,963 | 1,139 | 822 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Antecedent AGC | ||||||||||

| One negative Pap | 1,242 | 1,059 | 174 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| One negative HPV test | 1,014 | 872 | 139 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| One negative cotest | 901 | 791 | 110 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antecedent ASC-H | ||||||||||

| One negative Pap | 798 | 521 | 256 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| One negative HPV test | 550 | 383 | 158 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| One negative cotest | 456 | 326 | 127 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Antecedent HSIL+ | ||||||||||

| One negative Pap | 286 | 166 | 111 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| One negative HPV test | 185 | 109 | 70 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| One negative cotest | 144 | 89 | 54 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: Total cancer includes not only squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma but also adenosquamous carcinoma, and cervical cancer of unknown histology or histology unrelated to HPV infection. “HSIL+” includes HSIL and the few women with SCC and AIS Paps.

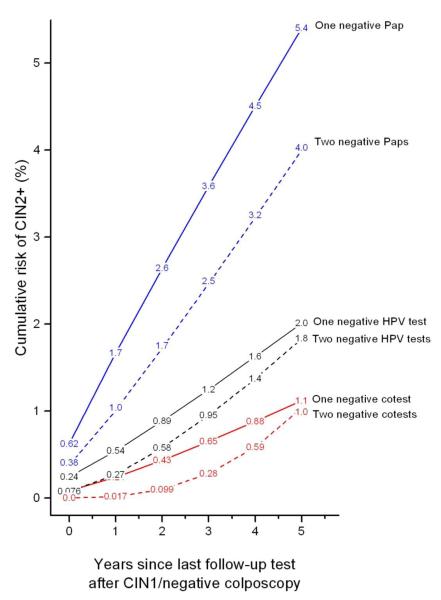

Figure 3 shows CIN2+ risks following negative follow-up tests for women with CIN1/negative colposcopy and antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL under 3 management strategies (Pap-alone, HPV-alone and cotesting). With 2 negative follow-up tests, the subsequent 5-year CIN2+ risk tended to decrease but only slightly (1 negative Pap result vs. 2 negative Pap result: 5.4% vs. 4.0% (p=0.08)); 1 negative HPV test vs. 2 negative HPV tests: 2.0% vs. 1.8% (p=0.9); 1 negative cotest vs. 2 negative cotests: 1.1% vs. 1.0% (p=0.9)). Most importantly, a single negative cotest conferred lower subsequent 5-year risk of CIN2+ (1.1%; 95%CI: 0.7% to 1.9%) than 2 negative HPV tests (1.8%, p=0.3) or 2 negative Pap results (4.0%, p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Cumulative risk of CIN2+ following CIN1/negative colposcopy given subsequent (consecutively) negative follow-up test(s), among women aged 25 and older with antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL. The negative Pap test curves are for all Pap results alone regardless of HPV test results and the HPV negative test curves are for all HPV results alone regardless of Pap test results. A “negative cotest” means testing both HPV-negative and Pap-negative.

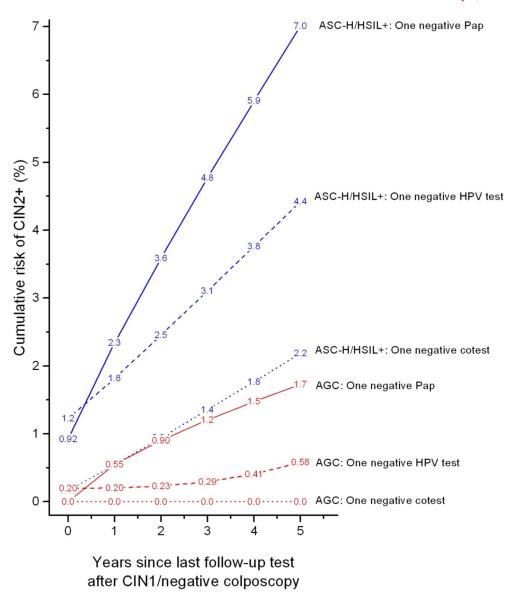

Figure 4 shows CIN2+ risks for women following negative follow-up tests among women with CIN1/negative colposcopy and antecedent ASC-H/HSIL+ or AGC under 3 management strategies (Pap-alone, HPV-alone and cotesting). A single negative cotest conferred lower risk than a single negative HPV test or Pap test. For ASC-H/HSIL+ antecedent Paps, the lowest CIN2+ risk occurred after 1 negative cotest (2.2%, 95%CI 0.7% to 6.9%) rather than 1 negative HPV test (4.4%, p=0.4) or a single negative Pap (7.0%, p=0.06). For antecedent AGC Pap results, the lowest CIN2+ risk again occurred after 1 negative cotest (0%, 95%CI 0% to 3.4%) versus 1 negative HPV test (0.58%, p=0.09) or 1 negative Pap (1.7%, p=0.07). We had insufficient numbers to address 2 consecutively negative follow-up tests with antecedent ASC-H/HSIL+ or AGC.

Figure 4.

Cumulative risk of CIN2+ following CIN1/negative colposcopy given antecedent ASC-H/HSIL+ (Blue lines) or AGC (Red lines) and negative follow-up test, among women aged 25 and older. The negative Pap test curves are for all Pap results alone regardless of HPV test results and the HPV negative test curves are for all HPV results alone regardless of Pap test results.

Table 3 benchmarks 5-year CIN2+ risk for negative follow-up tests after CIN1/negative colposcopy for antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL to the risk thresholds for management of screening Pap test results (8). Post-colposcopy Pap-negative risks were similar to those that in the screening context entail a 6-12 month return, such as ASCUS (6.9%). The post-colposcopy HPV-negative risks were intermediate between risk thresholds for a 1- and 3-year return. The post-colposcopy negative cotest risks were similar to risk thresholds for a 3-year return, in particular, the 0.68% 5-year CIN2+ risk among screening Pap-negative women. However, no negative test result following CIN1/negative colposcopy ever reached the ultra-low risk threshold of 0.27% 5-year CIN2+ risk currently required for a 5-year return.

Table 3.

Benchmarking CIN2+ risks for negative follow-up tests following CIN1/negative colposcopy with antecedent HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL in women aged 25 and older, to CIN2+ risk thresholds implicitly used to determine clinical management options based on screening Pap tests.

| Current recommended management strategy based on Pap-alone screening |

Implicit risk threshold: 5-year CIN2+ risk (%)1 by baseline Pap-alonea result |

Women with CIN1/negative colposcopy after HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL aged 25 and older |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up with Pap-alonea |

Follow-up with HPV testing-aloneb |

Follow-up with cotesting |

|||||

| Pap result(s) | 5-year CIN2+ risk after last test |

HPV test result(s) | 5-year CIN2+ risk after last test |

HPV/Pap result(s) |

5-year CIN2+ risk after last test |

||

| Immediate colposcopy |

LSIL: 16% | ||||||

| 6-12 month return | ASC-US: 6.9% | 1 negative Pap 2 negative Paps |

5.4% 4.0% |

||||

| Intermediate | 1 negative HPV test 2 negative HPV tests |

2.0% 1.8% |

|||||

| 3-year return | Pap-negative: 0.68% | 1 negative cotest 2 negative cotests |

1.1% 1.0% |

||||

Follow-up Pap result(s) alone (regardless of HPV test result)

Follow-up HPV test result(s) alone (regardless of Pap result)

Data presented in: Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, et al. Benchmarking CIN3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines J Low Genit Tract Dis In press.

Table 4 benchmarks 5-year CIN2+ risk for negative follow-up tests after CIN1/negative colposcopy for antecedent ASC-H/HSIL+ or AGC to the risk thresholds for management of screening test results. For antecedent ASC-H/HSIL+, none of the follow-up test strategies had a risk approaching the implicit risk for Pap-negative results (0.68%) for which a 3-year return is recommended (10). For AGC, 1 negative HPV test had a risk of 0.58% (95%CI: 0.1% to 2.3%), similar to the 3-year return threshold, although the confidence interval was wide. The risk estimate for women with a negative cotest was uncertain due to sparse outcome data. Of note, unlike CIN2+ risks, the cancer risks with antecedent AGC were high (1 negative Pap had a risk of 0.18% (95%CI: 0.02% to 1.4%) and 1 negative HPV test had a risk of 0.38% (95%CI: 0.05% to 2.7%)) which were comparable to the cancer risks after screening results of LSIL (0.16%) or HPV-positive/ASC-US (0.41%) for which immediate colposcopy is recommended (10).

Table 4.

Benchmarking CIN2+ risks for negative follow-up tests following CIN1/negative colposcopy with antecedent ASC-H/HSIL or AGC in women aged 25 and older, to CIN2+ risk thresholds implicitly used to determine clinical management options based on screening Pap tests.

| Current recommended management strategy based on Pap-alone screening |

Implicit risk threshold: 5-year CIN2+ risk (%)1 by baseline Pap-alonea result |

Women with CIN1/negative colposcopy aged 25 and older |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASC-H/HSIL+ Pap result antecedent to colposcopy |

AGC Pap result antecedent to colposcopy |

||||

| Follow-up result post-colposcopy |

5-year CIN2+ risk after follow-up test |

Follow-up result post-colposcopy |

5-year CIN2+ risk after follow-up test |

||

| Immediate colposcopy |

LSIL: 16% | ||||

| 6-12 month return | ASC-US: 6.9% 1 | negative Papa 1 negative HPV testb |

7.0% 4.4% |

||

| Intermediate | 1 negative cotest | 2.2% | 1 negative Papa | 1.7% | |

| 3-year return | Pap-negative: 0.68% | 1 negative HPV testb | 0.58% | ||

Note: For women with an antecedent AGC, the cancer risk remained high, justifying managing AGC similarly to ASC-H or HSIL+.

Zero CIN2+ were detected among women with an antecedent AGC and 1 negative follow-up cotest.

Follow-up Pap result(s) alone (regardless of HPV test result)

Follow-up HPV test result(s) alone (regardless of Pap result)

Data presented in: Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, et al. Benchmarking CIN3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines J Low Genit Tract Dis In press.

Discussion

Our data suggest that having a CIN1/negative colposcopy lowers 5-year risk of CIN2+ among women with abnormal screening tests referred to colposcopy; however, substantial risk remains. For women referred for colposcopy for HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL, a single negative cotest after CIN1/negative colposcopy confers substantial reassurance against subsequent CIN2+. In contrast, for women referred for colposcopy for AGC/ASC-H/HSIL+, a single negative Pap/HPV/cotest appears to confer less reassurance against CIN2+. Unfortunately, no sequence of negative tests after colposcopy for any indication reduces CIN2+ risk to a level sufficiently safe to return to 5-year screening intervals. Still, cotesting provides the most reassurance with the fewest number of follow-up tests.

The majority (84%) of women with a CIN1 or negative colposcopy had a low-grade antecedent screening result (HPV-positive/ASC-US or LSIL). Following a single negative cotest, their risk was reduced to a level sufficiently low to consider a 3-year return. Notably, a single negative cotest provided more reassurance against CIN2+ than 2 negative HPV tests or 2 negative Paps. A similar relationship was reported in the ASCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS), in which the 2-year CIN2+ risks were higher overall: 1.8% after 1 follow-up negative cotest, 2.4% after a follow-up HPV-negative test and 4.6% after a follow-up negative Pap (11). A second negative cotest did not add additional risk reduction over a single negative cotest. In the KPNC population, 46% of women with a low-grade antecedent screening result, followed with cotesting, were negative at their first follow-up test, suggesting that perhaps up to half of these women could be spared yearly intensive colposcopy and returned to a 3-year testing interval.

A minority (16%) of women with a CIN1 or negative colposcopy had a high grade antecedent screening result (AGC, ASC-H, or HSIL+), but a majority (62%) of the cancers occurred in these women. No single negative test result conferred low enough risk to consider a 3-year rather than a 1-year return; unfortunately, insufficient data existed to calculate risk after more than 1 negative test result. For women with antecedent AGC, although few CIN2 were diagnosed after a subsequent negative test result, the cancer risk remained high, justifying managing AGC similarly to ASC-H or HSIL+.

Ideally, a randomized trial comparing 3 follow-up strategies after a CIN1/negative histology, or negative colposcopy (Pap-alone, HPV-alone or cotesting) would best identify the correct management to determine when it is safe for a woman to return to routine screening. In the absence of such a study, we analyzed observational data from a large integrated health system that utilizes cotesting. There are important limitations to this analysis. Because findings were similar, we combined CIN1 with normal biopsy and also combined some antecedent screening test results. Due to few outcomes, we were unable to characterize the risks of women referred to colposcopy for repeat HPV-positive/Pap-negative screening cotests. We did not have enough information to consider the effect of age, so we combined all women age 25 and older.

In addition, our analytic sample was defined by histology records, so that in the absence of a biopsy result, we were unable to distinguish between women with a normal colposcopy without biopsy vs. women missing colposcopy between their antecedent screen and follow-up test. For antecedent HSIL+, 15% were without biopsy, but for other screening abnormalities 30-40% were without biopsy. Chart reviews suggested that most women likely had a colposcopy exam between their screening abnormality and follow-up test. We have assumed that, given the low risk of CIN2+ between a baseline screen and later normal Pap or cotest, almost all women missing colposcopy would have had a CIN1/negative result (especially if their future Pap/HPV/cotest was negative). An ancillary analysis of women without biopsy results showed similar 5-year CIN2+ risks compared to women with CIN1 or negative biopsy results.

Finally, our analysis estimated CIN2+ risks after negative follow-up Pap results taken from either Pap tests alone or in the context of cotesting. It is likely that women with an HPV-positive/Pap-negative cotest are followed more closely than a Pap-negative test alone, thereby detecting more CIN2+ and likely overestimating the short-term risks after a negative Pap. However, we assumed that Pap-alone would likely have identified within 5 years any true persistent treatable lesion found earlier by cotesting, so we focused on 5-year risk calculations. The only definitive way to resolve this issue would be a trial to randomize women to cotesting versus Pap-alone.

Our findings suggest that cotesting may be better than Pap-alone or HPV-alone testing for following women after colposcopy. More data are required to determine how many more negative cotests are required to permit returning women to routine 5-year screening, especially for women referred for colposcopy by high-grade Pap tests and not initially found to have CIN2+.

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source The funding sources did not review or approve the study design and were not involved in data collection, analysis, interpretation, or in writing the paper. The Intramural Research Program of the US National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute and Kaiser Permanente Northern California reviewed the final manuscript for publication. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved use of the data, and the National Institutes of Health Office of Human Subjects Research deemed this study exempt from IRB review.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Schiffman and Dr. Gage report working with Qiagen, Inc. on an independent evaluation of non-commercial uses of CareHPV (a low-cost HPV test for low-resource regions) for which they have received research reagents and technical aid from Qiagen at no cost. They have received HPV testing for research at no cost from Roche. Dr. Castle has received compensation for serving as a member of a Data and Safety Monitoring Board for HPV vaccines for Merck. Dr. Castle has received HPV tests and testing for research at a reduced or no cost from Qiagen, Roche, MTM, and Norchip. Dr. Castle is a paid consultant for BD, GE Healthcare, and Cepheid, and has received a speaker honorarium from Roche. No other authors report any conflicts of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moyer VA. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880–91. W312. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain JM, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16(3):175–204. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31824ca9d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright TC, Jr., Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11(4):223–39. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318159408b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostor AG. Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12(2):186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melnikow J, Nuovo J, Willan AR, Chan BK, Howell LP. Natural history of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(4 Pt 2):727–35. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox JT, Schiffman M, Solomon D. Prospective follow-up suggests similar risk of subsequent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 among women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 or negative colposcopy and directed biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(6):1406–12. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pretorius RG, Peterson P, Azizi F, Burchette RJ. Subsequent risk and presentation of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3 or cancer after a colposcopic diagnosis of CIN 1 or less. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, et al. Benchmarking CIN3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318285423c. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2114–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, et al. Five-year risk of cervical cancer and CIN3 for HPV-positive and HPV-negative high-grade Pap results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182854282. To be submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker JL, Wang SS, Schiffman M, Solomon D. Predicting absolute risk of CIN3 during post-colposcopic follow-up: results from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(2):341–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]