Abstract

It is unclear how genomic incidental finding (GIF) prospects should be addressed in informed consent processes. An exploratory study on this topic was conducted with 34 purposively sampled Chairs of institutional review boards (IRBs) at centers conducting genome-wide association studies. Most Chairs (96%) reported no knowledge of local IRB requirements regarding GIFs and informed consent. Chairs suggested consent processes should address the prospect of, and study disclosure policy on, GIFs; GIF management and follow-up; potential clinical significance of GIFs; potential risks of GIF disclosure; an opportunity for participants to opt out of GIF disclosure; and duration of the researcher's duty to disclose GIFs. Chairs were concerned about participant disclosure preferences changing over time; inherent limitations in determining the scope and accuracy of claims about GIFs; and making consent processes longer and more complex. IRB Chair and other stakeholder perspectives can help advance informed consent efforts to accommodate GIF prospects.

Keywords: informed consent, genomic incidental findings, institutional review board

Genomic research may generate individual genetic research results (IGRRs) as a component of a research study's aims, or genomic incidental findings (GIFs) not related to a study's aims. Some IGRRs and GIFs may have important health implications for research participants and their biological families, which has led experts to argue that IGRRs and GIFs should, in certain circumstances, be disclosed to research participants (Beskow & Burke, 2010; Bookman et al., 2006; Caulfield et al., 2008; Fabsitz et al., 2010). Plans to disclose IGRRs and GIFs also raise the question of whether and how potential research participants should be informed about the eventuality of IGRR and GIF disclosure.

This question is driven in part by the potential and variable risks associated with IGRR and GIF discovery and disclosure, including the potential for misinterpreting the relevance of an IGRR or GIF and receiving false reassurances or unnecessary scares; potential loss of privacy and confidentiality through disclosure; insurability issues; and possible social discrimination and/or stigmatization (Apold & Downie, 2011; Dressler, 2009; S. M. Wolf et al., 2008). While current federal informed consent requirements do not explicitly address the prospect of IGRRs and GIFs, they do stipulate that potential research participants be provided with a description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts associated with participation in a research study (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

Some scholars have questioned whether the tradition of informed consent is up to the task of addressing the unique elements of genomic research, particularly given the many problems that have been empirically associated with informed consent (Henderson, 2011; Winickoff & Winickoff, 2003). Others recognize that there will be challenges, but that informed consent practices can be tailored to the distinctive characteristics of genomic research (Rotimi & Marshall, 2010). National-level entities, including the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), provide guidelines recommending that informed consent processes include a spectrum of information on the prospects of IGRR discovery and disclosure in research (Bookman et al., 2006; Fabsitz et al., 2010).

These developments are important, but have not yet focused closely on the need for and practicalities of addressing GIF prospects through informed consent. We conducted an exploratory descriptive study to gain a preliminary understanding of emerging institutional review board (IRB) perspectives and practices in regard to the addressing of GIFs in informed consent processes. Despite key work on emerging IRB practices with respect to genetic and genomic research with human participants (Keane, 2008; Kozanczyn, Collins, & Fernandez, 2007; L. E. Wolf et al., 2008), it is unclear whether and how IRBs are addressing the prospect of GIFs and IGRRs through the tradition of informed consent. There is currently no national-level policy governing the disclosure of GIFs in research, nor is there necessarily agreement that such a policy is needed. Local IRB practices may provide valuable insight into whether and how the prospect of GIF discovery and disclosure is addressed in informed consent processes.

Characterizing GIFs

Incidental findings (IFs) are a distinctive research result. An IF has been defined as “a finding concerning an individual research participant that has potential health or reproductive importance and is discovered in the course of conduct ing research but is beyond the aims of the study” (S. M. Wolf et al., 2008, p. 2). Following this definition, GIFs might comprise a genetic or chromosomal variant of potential health importance that was found on a research-generated genomic microarray, but not “looked for” in that research study. The question of whether or not GIFs should be shared with research participants prompts consideration of multiple factors, including the reliability of the test that led to the GIF discovery; whether enough is known to make sense of the finding and what it may mean for a research participant's health; the expense to investigators or research sponsors of verifying a GIF; the potential for GIF implications to change over time with increasing knowledge; and the potential for GIF disclosure to harm research participants through, for example, breaches of confidentiality or privacy, discrimination, loss of health insurance, or emotional distress (Cho, 2008; Parker, 2008; S. M. Wolf et al., 2008).

One complication characterizing GIFs is that they may not be equally incidental or unexpected (Cho, 2008; Parker, 2008). For example, while the discovery of misattributed paternity may be unrelated to the aims or goals of a genetic family study, and therefore considered to be incidental (S. M. Wolf et al., 2008), this finding could be seen as not entirely unexpected given the focus of the study on inheritance of maternal and paternal alleles to their offspring. In this case, there may be an expectation that the researchers have a clear plan in place for managing the potential finding of misattributed paternity. By contrast, a GIF associated with a disease such as diabetes or breast cancer could be seen as notably more unpredictable and challenging to manage if discovered over the course of a study researching a different disease, such as Alzheimer disease (Couzin-Frankel, 2011). In this case, the issue of whether research participants should be informed and whether researchers need to have a plan in place with respect to the possible discovery of any incidental findings is not as clear-cut. This variability in the level of unexpectedness surrounding GIFs may affect whether or not researchers may have, or believe they have, a duty to inform participants about a GIF, and how feasible it is for them to do so (Parker, 2008).

Terminology

The determination of whether and what kind of GIFs should be disclosed to research participants continues to be examined. Multiple terms have been used to qualify what kind(s) of GIFs or IGRRs should be returned to research participants, including terms such as “clinical implication,” “strong net benefit,” “clinical utility,” and “medically actionable” findings (Bookman et al., 2006; Burke et al., 2002; S. M. Wolf et al., 2008). Recent guidelines from Fabsitz et al. (2010) refer to IGRRs with “important health implications” as one among several qualifiers for IGRRs that may warrant disclosure. To our knowledge, consensus has yet to be reached on this terminology (S.M. Wolf, 2011). In an ongoing examination of GIFs, S.M. Wolf et al. (2008) recommend a classification of research results referred to as having “strong net benefit,” which includes results revealing a condition that is likely to be life-threatening; is likely to be grave but that can be avoided or ameliorated; poses a significant risk of a condition likely to be life threatening; or involves genetic information that can be used to avoid or ameliorate a condition likely to be grave and has use in reproductive decision making.

In this paper, we follow the Fabsitz et al. (2010) guidelines on IGRRs and consider IGRRs and GIFs as potentially returnable if, among other factors, they have “important health implications” for research participants. We recognize that this definition could encompass a broad spectrum of IGRRs and GIFs and health implications. However, given that terminology and criteria for determining the returnability of IGRRs and GIFs continue to be refined, we prefer at this point in time not to adopt more restrictive terminology.

IGRRs, GIFs, and Informed Consent

To date, the Common Rule, or Title 45 CFR 46 federal regulations governing informed consent in research, do not directly specify a need for researchers to convey information about the prospect of IGRRs or GIFs to potential research participants (Tovino, 2008). However, recommendations and guidelines have been proposed for purposes of broadening informed consent processes to include the prospect of IGRRs generally (Bookman et al., 2006; Caulfield et al., 2008; Fabsitz et al., 2010; McGuire & Beskow, 2010; Miller, Mello, & Joffe, 2008; Office of Biorepositiories and Biospecimen Research, 2010a; Office of Biorepositories and Biospecimen Research, 2010b). In 2006, a working group of the NHLBI recommended that researchers address in their informed consent processes, where appropriate, the prospect of returning IGRRs “with personal health implications, implications for family members, and reproductive implications” (Bookman et al., 2006). The working group recommended that individuals be provided with an explanation of the potential relevance of the genetic results, including any risks of harm or potential for benefits for participants, their families, or communities (Bookman et al., 2006). A more recent set of NHLBI guidelines recommends that informed consent processes describe the researchers’ plans for managing the return of IGRRs, and provide an opportunity for research participants to opt in or out of receiving results (Fabsitz et al., 2010). The guidelines recommend that informed consent processes include a statement that IGRRs will ordinarily not be returned after the research award period ends (Fabsitz et al., 2010). GIFs are not the specific target of the NHLBI's guidelines, yet the criteria for disclosing IGRRs generally put forth in these documents may in certain circumstances apply to GIFs. Nonetheless, given the distinctive nature and context of GIFs as briefly reviewed above, it is unclear whether and how the prospect of GIFs needs to be addressed for the purposes of informed consent, and whether for specific research studies it is acceptable not to address the prospect of GIFs, or to address only the prospect of IGRRs in general, or even potentially to address the prospects of both GIFs and IGRRs.

The genomic era continues to evolve. Traditional approaches to informed consent may not be ideally suited to the specific contexts of genomic research and testing, and may become unwieldy or even untenable if consent cannot be obtained in a reasonable time frame (Berg, Khoury, & Evans, 2011; Henderson, 2011). At the same time, there are innovative ways of addressing challenges such as the length, complexity, and cultural specificity of informed consent processes (Beskow et al., 2010; Gikonyo et al., 2008), which may merit exploration in the context of genomic informed consent and the prospect of GIFs and IGRRs. This study takes a step toward better understanding if and how informed consent practices can accommodate the prospect for GIFs in genomic research from the perspective of one key stakeholder group, the Chairs of IRBs.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of IRB Chairs at U.S. centers with published affiliations to genome-wide association studies (GWAS). We focused on IRBs at these centers because GWAS are part of the first generation of genomic research studies that emerged subsequent to the complete mapping of the human genome. GWAS have led to the discovery of thousands of genetic variants contributing to variability in a range of common diseases including diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease (Johnson et al., 2010; Johnson & O'Donnell, 2009). It has been noted that few, if any, potentially “notifiable” variants reside on arrays used in GWAS (Johnson et al., 2010). However, this conclusion was arrived at using a more stringent set of criteria for determining the notifiability of IGRRs (Bookman et al., 2006), and not the criteria recommended by the more recent NHLBI workshop on the return of IGRRs (Fabsitz et al., 2010). Research is still needed on the potential notifiability and frequency of incidental GWAS variants using these more recent criteria. Nonetheless, GWAS foreshadow the challenges that the next-generation sequencing methods, including whole-genome sequencing (WGS), are expected to generate with respect to the return of IGRRs and GIFs with personal health and/or family health implications (Caulfield et al., 2008; S. M. Wolf, 2008).

The study was conducted by researchers at the University of Iowa, with data collection support from the Center of Social and Behavioral Research (CSBR) at the University of Northern Iowa. The study was approved by IRBs at both universities. IRB Chairs were considered eligible for this study if they were U.S.-based, English speaking, and actively chairing IRBs at degree- or non-degree-granting institutions engaged in GWAS (including federal institutions such as the NIH). VA-based IRBs were excluded from consideration owing to feasibility issues. To identify eligible Chairs, we first reviewed (between November 10, 2008 and November 9, 2009) all abstracts in the National Human Genome Research Institute's (NHGRI's) electronic catalog of published GWAS (http://www.genome.gov/26525384). We located 202 publications reporting on GWAS with human subjects. We used the addresses or affiliations of the corresponding authors to identify 56 different U.S. institutions that potentially were involved in GWAS. Next, we searched (on November 8, 2009) GWAS grant abstracts in the NIH's Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tool (RePORTER), using the acronym, “GWAS.” This search yielded 129 abstracts of GWAS studies with human subjects. We then merged the two lists, which identified 93 unique institutions. An additional 54 institutions were identified using the Heartland Regional Genetics and Newborn Screening Collaborative website (http://www.heartlandcollaborative.org/default.asp), Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) institution websites, and Google searches for GWAS consortia referred to in NIH RePORTER abstracts. The final list, completed in March 2010, contained the names of 147 unique GWAS-active institutions (98 degree granting and 49 non-degree granting).

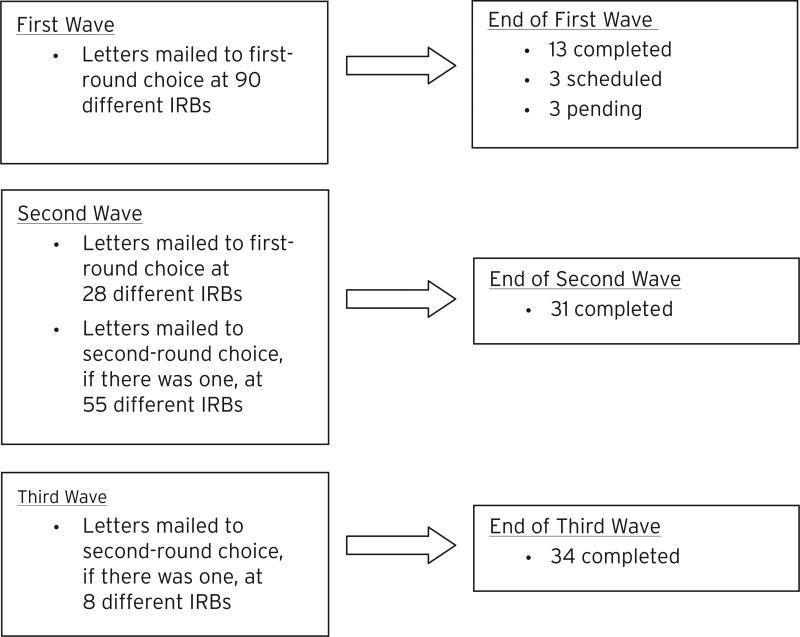

Next, we searched for the public websites of these 147 institutions in an effort to obtain contact information about their Biomedical IRBs. A total of 118 Biomedical IRBs with an accessible online website were identified. IRB websites frequently listed more than one active Chair, as well as their names and work addresses. Where multiple Chairs were listed, we selected the executive or primary Chair as a first-round choice for recruitment. Since we expected Biomedical IRB Chairs to be predominantly MDs, we oversampled Chairs with PhDs to promote diversity of professional backgrounds in our sample. Recruitment letters were surface mailed in three waves over a four-month period. Interested Chairs were invited to call or e-mail the CSBR to obtain additional information about the study and/or schedule an individual telephone interview. A total of 181 Chairs (i.e., up to two per institution) were sent a recruitment letter (see Figure 1 for details).

Fig. 1.

Recruitment Diagram.

Individual telephone interviews with consented IRB Chairs were audiotaped and conducted from March 30, 2010 to November 12, 2010. A semi-structured interview guide was used containing open-ended and closed-ended questions. All interview questions that sourced data for this report are listed in Table 1 (full interview guide available on request). The interview guide was developed with extensive input from experienced interview and survey methodologists, and was reviewed by an experienced local IRB Chair and IRB Board member, who were asked to critically evaluate and provide feedback on the guide. The audiotaped interviews were closely reviewed, and detailed debriefings with the interviewers were conducted throughout the study for quality control purposes. One question (see Table 1) was added to the guide after interview #5 was completed; no other changes were necessary.

TABLE 1.

Relevant (28 of 76) Interview Guide Questions.

| Interview Questions |

|---|

| To begin, what comes to mind when you hear the words, incidental finding? |

| Does anything else come to mind when I add the words, genetic or genomic incidental finding? |

| What information about incidental findings, if any, do you think should be included in consent documents for genetic or genomic research studies? |

| [Prompt if necessary: What about information regarding the relative likelihood of an incidental finding occurring? What about information regarding how an incidental finding would be handled? What other information, if any, should be included in consent documents?] |

| Why do you think this information should be included? |

| What information about incidental findings, if any, do you think should not be included in consent documents for genetic or genomic research studies? |

| [Prompt if necessary: What about information regarding the relative likelihood of an incidental finding occurring? What about information regarding how an incidental finding would be handled? What about information about who will be responsible for handling the incidental finding?] |

| Why do you think this information should not be included? |

| What kinds of information, if any, does your IRB require in consent documents with respect to genetic or genomic incidental findings? [Prompt if necessary: What about information regarding the relative likelihood of an incidental finding occurring? What about information regarding how an incidental finding would be handled? What other information, if any, should be included in consent documents?]* |

| *This question was introduced to the Guide after the start of the interview study; as a result, it was asked of fewer (29) IRB Chairs. |

| What are the potential benefits of providing genetic or genomic research subjects with the option of receiving or not receiving incidental findings? |

| Would you define your IRB as a “biomedical” IRB? |

| IF NOT: How would you define it? |

| More or less how many new, resubmitted, or other protocols are reviewed by the full board of your IRB every month? |

| Roughly what percentage of these protocols is genetic or genomic in focus? |

| In the past 12 months, how many full board meetings have you attended where there has been discussion of incidental findings in genetic or nongenetic research? |

| IF RESPONDENT REPORTS SOME NUMBER OF MEETINGS: In how many of these meetings was the discussion about genetic or genomic incidental findings? |

| Do you anticipate that the number of such discussions at full board meetings will in the future increase, decrease, or stay about the same? |

| And you are [MALE / FEMALE]. |

| IF NOT SURE: What is your gender? |

| And what is your age?_ |

| IF NO SPECIFIC AGE PROVIDED: Could you please tell me which age bracket you fall into? Would you say 18-25; 26-35; 36-45; 46-55; 56-65; or 65 plus? |

| In which of the following regions is your IRB located? |

| West or Northwestern United States |

| East or Southeastern United States |

| Southwestern United States |

| The Midwest or Heartland |

| Is your IRB based at a degree-granting institution? |

| What is the highest academic degree that you have earned? [PLEASE SPECIFY] |

| How long have you been a Chairperson on your IRB? |

| Do you currently or have you ever conducted research with human subjects? |

| What is the general focus of your research? |

| Have you ever encountered incidental findings in your own research? |

| Were these genetic or genomic incidental findings? |

| How would you rate your knowledge and awareness of the issues surrounding genetic or genomic incidental findings? Would you say your knowledge and awareness is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor? |

| Are you Hispanic or Latino? |

| Which of the following racial categories, if any, would you put yourself in? |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native Asian |

| Black or African American |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander |

| White (this includes persons having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa) |

| Would you put yourself in any other racial category? [If so, please specify which category or categories] |

Audiotaped interviews lasted an average of 30 minutes (range = 15–52 minutes). While 20–60 participants were originally proposed, preliminary data analysis indicated that data saturation was reached following 34 interviews. The CSBR transcribed the audiotaped interviews and validated all transcriptions. Interview questions were analyzed using conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Two members of the research team independently read and coded each transcript. A coding guide was developed and refined on an ongoing basis to identify themes and define coding parameters. Weekly meetings were held to reconcile codes and reach consensus. To verify codes and help interpret the data, a third team member independently coded the questions of interest in this paper and participated in data analysis. NVivo (2008) was used for management of the coded transcripts. Demographic data from the interviews were managed in Excel and analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Demographic and Background Data

IRB Chairs and IRBs

Tables 2 and 3 present select data about IRB Chairs and the IRBs they chair. Chairs were predominantly male (79%) and White (91%), and half (50%) had PhDs. The majority (82%) of IRBs represented in this study were based at degree-granting institutions, with the greatest proportion concentrated in the eastern or southeastern U.S. Their protocol reviews included genetic/genomic research, among other types of research. Chairs reported having an average of five years of experience chairing an IRB. The majority (88%) reported also having experience conducting research with human participants. Of these Chairs, eight had encountered IFs (27%) in their own research, and one had encountered GIFs over the course of his/her research experience. Self-rated knowledge/awareness of GIF issues was widely distributed across a five-point scale ranging from poor to excellent. The majority (71%) of Chairs expected an increase in the future need of their IRBs to engage with the topic of GIFs.

TABLE 2.

Profile of IRB Chairs (n=34).

| Background Data | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 27 | 79% |

| Male | 7 | 21% |

| Female | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 31 | 91% |

| Other | 1 | 3% |

| Unclear/data not provided | 2 | 6% |

| Age | ||

| Average (Range) | 56 (39-75) | – |

| Highest academic degree | ||

| PhD | 17 | 50% |

| MD | 10 | 29% |

| MD, PhD | 1 | 3% |

| Other | 6 | 18% |

| Years of experience chairing an IRB (average and range, in yrs) | 5 (1-12) | – |

| Experience conducting research with human subjects | 30 | 88% |

| Encountered IFs in own research | 8 | 27% |

| Encountered GIFs in own research | 1 | 3% |

| Self-rated knowledge/awareness of GIF issues: | ||

| Excellent | 4 | 12% |

| Very Good | 8 | 24% |

| Good | 11 | 32% |

| Fair | 10 | 29% |

| Poor | 1 | 3% |

TABLE 3.

Profile of Represented IRBs (n=34).

| Background Data | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Region/USA | ||

| West or Northwest | 5 | 15% |

| East or Southeast | 18 | 53% |

| Southwest | 2 | 6% |

| Midwest | 9 | 26% |

| Institution Type | ||

| Degree granting | 28 | 82% |

| Non-degree granting | 6 | 18% |

| IRB Type | ||

| Biomedical | 27 | 79% |

| Behavioral | 1 | 3% |

| Both | 6 | 18% |

| % of Protocols With a Genetic/Genomic Focus: | ||

| Less than 5% | 7 | 20% |

| 5-10% | 14 | 41% |

| 11-25% | 6 | 18% |

| Greater than 25% | 5 | 15% |

| Unclear/missing | 2 | 6% |

| Has your IRB ever engaged in discussions about GIFs? | 25 (yes) | 74% |

| Do you expect your IRB's need to discuss GIFs will: | ||

| Increase? | 24 | 71% |

| Decrease? | 1 | 3% |

| Stay the same? | 9 | 26% |

Chairs were asked, “What comes to mind when you hear the words, ‘incidental finding’” and “Does anything else come to mind when I add the words, genetic or genomic incidental finding?” Chairs used one or more descriptors to characterize IFs and GIFs, including “unexpected,” “unrelated,” and “clinical significance.” While they were not specifically asked to comment on the possible differences between IFs and GIFs, the majority (74%) of Chairs suggested that GIFs were different from IFs. Cited differences included the presumed “vagueness” of GIF significance; less likelihood of GIFs offering a possible benefit; more likelihood of GIFs affecting more people, including biological family; and having broader social implications, including discriminatory and stigmatizing effects.

IRB Requirements for Informed Consent and GIFs

Twenty-nine Chairs were asked what kinds of information, if any, their IRBs required researchers to include in informed consent documents with respect to GIFs. Only one Chair reported that his/her IRB had GIF-specific requirements, yet described this requirement as relatively informal:

To my knowledge it's not a formal requirement, but it is something that we do so routinely that it's become a de facto requirement....We always require a full statement of risks and this would include in genomic incidental findings the risk of job discrimination, the risk of, you know, future anxiety, concern and stress, emotional reaction to the news, risk of insurance loss. (Participant #1)

The remaining Chairs reported that their IRBs had no requirements pursuant to GIFs or IFs (41%), or that their IRB requirements were limited, indirect, and relatively generic (55%), for example:

[We have] generic language that any genetic study could involve loss of confidentiality of information....That's the only thing that's required and that's pretty generic, it's not specific to the incidental findings. [I]t's generic for any findings relating to the genetic study. (Participant #2)

GIF Information Suggested for Inclusion in IC Processes

A total of 33 (97%) IRB Chairs chose to answer the question, “What information about incidental findings, if any, do you think should be included in consent documents for genetic or genomic research studies?” (one respondent abstained). Seven categories of information were identified (see Table 4). Below, we summarize these categories of information using numerical data to indicate what number and proportion of Chairs made suggestions that were coded into each of these seven categories of information. We provide qualitative data (i.e., direct quotes) to illustrate typical content within each category of information. The categories are described in descending order of frequency.

TABLE 4.

IRB Chair Suggested Information for Informed Consent Processes per GIFs.

| Suggested Informed Consent Information on GIFs | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Prospect of and study disclosure policy on GIFs | 18 | 55% |

| GIF management plans | 16 | 48% |

| Potential clinical significance of GIFs | 14 | 42% |

| Potential risks of GIF disclosure | 11 | 33% |

| Elicit GIF disclosure preferences | 9 | 27% |

| Definition of GIFs | 2 | 6% |

| Duration of duty to disclose GIFs | 1 | 3% |

acknowledge GIF prospects and study disclosure policy

This was the most common suggestion made, and was made by just more than half (N = 18; 55%) of the IRB Chairs. In this category, Chairs suggested that informed consent processes needed to acknowledge when a research study had the potential to generate GIFs, for example: “At the very least, I think they should notify the subject that there is a possibility of discovery of findings that are both potentially beneficial and harmful to the subject” (Participant #5). Chairs who made this suggestion also recommended that researchers’ intentions with regard to GIF disclosure needed to be specified, for example: “They [researchers] have to say whether they will or will not reveal the results to the subjects” (Participant #6).

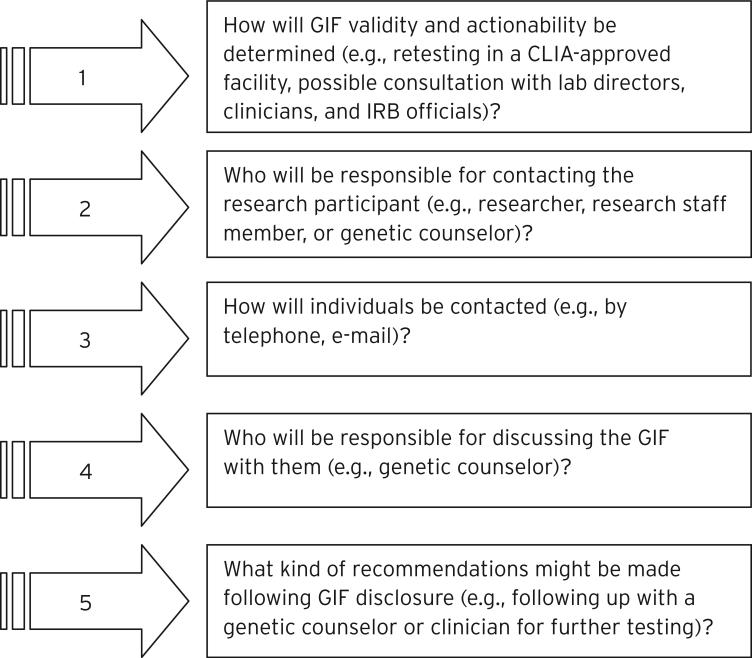

describe GIF management plans

Almost half (N = 16; 48%) of the Chairs volunteered that informed consent processes should outline the steps that would be taken to verify and disclose GIFs and to follow up on GIF disclosure. One Chair said that individuals “should be clearly told how [GIFs] will be handled. For example, will they be contacted, and under what circumstances would they be contacted” (Participant #10). Chairs suggested that informed consent processes should address a range of questions that potential research participants may want answered with respect to a research study's GIF management plans (see Figure 2). One Chair summed up the perceived need for this information as follows:

All of those elements, I think, need to be in documentation so that an individual will have a very clear understanding of who's going to know what, how it [the GIF] is going to be transmitted, who's going to handle it, and then what the responsibility of the institution is in these particular findings. (Participant #17)

Fig. 2.

Questions on GIF Management that Informed Consent Processes Should Address.

explain potential clinical significance of GIFs

A total of 14 Chairs (42%) recommended that informed consent processes address the potential clinical significance of GIFs. A typical example in this category includes: “People should be given a general understanding of the extent to which these [i.e., GIFs] have clinical significance” (Participant #10). Another Chair provided a greater level of detail:

I think in general subjects need to be aware that there's a future potential for identifying risk factors that may be of benefit to them, and give the subjects...sufficient information that they have an informed capacity to decide whether they want to be alerted of those risks in the future. (Participant #15)

Chairs emphasized that the concept of clinical significance needed to be carefully conveyed:

There should be no promise that the information will be used to help treat or prevent a disease.

I think it's important, I mean it should be stressed that participation in research is not therapy, it's not genetic testing so that you can get treatment, but it is possible that some information is discovered [that] may be relevant. (Participant #11)

Chairs suggested that consent processes should avoid implying that there could be a possible causal relationship between a GIF and the onset of disease, for example:

I think there should be information that explains to subjects that, especially in the genomic setting, that there are few diseases where the finding would actually be causally linked to a disease, and try to explain that having some kind of a finding, a genetic finding, does not necessarily mean that that subject will be getting that disease. (Participant #12)

Chairs pointed out the potential to cause anxiety or inappropriate decision making as a result of drawing certain causal connections in regard to GIFs:

I mean you could report those potential relationships [i.e., between GIFs and specific polymorphisms] to every patient who goes on a protocol and scare the daylights out of everybody, and there's virtually a rare chance that it could ever manifest, and I think that would be a huge disservice. (Participant #13)

Chairs emphasized that, from an IRB perspective, a key concern is that “people might act inappropriately or be given undue concern about incidental findings from which there isn't really solid clinical basis of what they mean” (Participant #8).

explain potential risks of GIF disclosure

A total of 11 Chairs (33%) commented on the need for informed consent processes to address the potential risks and benefits of GIF disclosure, for example: “My feeling about it would be that the person would have to...be informed about the potential risks...if there were to be any disclosure” (Participant #14). Chairs wanted to see informed consent processes address the potential for emotional, psychological, financial, or economic harm that may result from GIF disclosure, for example:

[Informed consent processes] should disclose that findings may upset people, may lead to some psychological concern and that there could potentially be some, oh, repercussions within family circles, and the need to sort of help people interpret and bring this to the awareness of other family members, if there is some likely effect. (Participant #16)

While Chairs acknowledged that loss of confidentiality was a possible risk of GIF disclosure, they saw this risk as being sufficiently addressed by existing informed consent language concerning confidentiality, as suggested by the following Chair:

We have sort of a standard thing for any genomic studies, you know, that one of the risks of being in a genetic study is loss of confidentiality, [that] potential genetic information could have unknown repercussions in terms of future insurance, et cetera. (Participant #2)

Chairs also suggested that the risks of GIF disclosure should not be exaggerated:

I think a general statement about the potential risks should be included. To be honest, I think the risks are somewhat overstated. I think there are protections in place, but I think this is an area that's of concern for patients, so...I think patients should be given this information. (Participant #1)

Chairs talked of the difficulty of documenting the potential for harm with regard to GIFs, given the unpredictability of their occurrence and significance:

It'll be hard to explain to them the statistics of this particular problem, but there's going to have to be an attempt made [by] somebody that's not a medical scientist, to understand what risk means. (Participant #12)

elicit participant disclosure preferences

A total of nine Chairs (27%) suggested that potential research participants be given an opportunity, during the informed consent process, to indicate whether or not they wanted GIFs disclosed to them. The provision of this choice was seen as a key way for researchers to respect the autonomy of individuals in regard to the prospect of GIFs. In the following example, a Chair underscores the perceived importance of autonomy in research by considering the possible need to overrule a participant's decision not to receive GIFs:

If, in the informed consent, the individuals have made the conclusion not to receive results, to force that upon them is to take a lot of responsibility because there are people who guide their own health care very carefully, and they choose or choose not to make decisions which many of us might think are foolish. But the nature of the informed consent process and of the research is actually quite different from that of the relationship, say, of a physician and his or her patient. In the case of research, we are giving great value to the issue of autonomy....” (Participant #8)

Chairs also commented on the challenges associated with efforts to document GIF disclosure preferences at the point of consent, for example:

Anytime you offer somebody the opportunity to express an opinion, you know, there's the possibility that they're going to change their mind.... That can be a little bit of a nuisance for the research coordinator or the investigator who has to deal with that. That's really the right of the patient or the subject to change their mind, so we have to be prepared to deal with that sort of eventuality. (Participant #9)

provide definition of GIFs

Two Chairs (6%) recommended that informed consent processes provide a simple definition or explanation of what GIFs are, for example:

I think a statement is needed that they [i.e., GIFs] exist and some simple explanation of what they are....Raising a whole lot of concepts which you need a reasonable background to grasp I don't think is useful in consenting people. (Participant #7)

specify duration of duty to disclose

One (3%) Chair commented on the need for informed consent processes to specify the length of time for which there would be an obligation to notify research participants about actionable GIFs. This Chair commented:

Limitations in terms of time periods, you know. For example if this is discovered beyond the termination date of the study, that there's no obligation to report. (Participant #13)

Additional Comments and Concerns

scope and accuracy of information

Chairs suggested that challenges would be involved in the effort to address GIFs in informed consent p rocesses, including with respect to the nature of the research and the scope and accuracy of information that can be provided. One Chair characterized this intersection of factors as follows:

If there's a previous indication that based on the type of study that you're doing...here's a good indication that you're gonna find an incidental finding, then I think it's worthwhile to disclose that, you know, there's a high likelihood that we will find an incidental finding that may have implications for other, you know, research, or other disease processes, whatever it may be.... If it's truly a fishing expedition—you don't know what you're gonna find—I think it's hard to disclose every, you know, different possibility out there. (Participant #18)

Another Chair commented more explicitly on the question of informational accuracy:

The dilemma, of course, is whatever incidental finding has been discovered...it's never clear how accurate that information is, how correct it is, and whether it is meaningful to the subject. (Participant #5)

added length and complexity

The possibility of confusing potential research participants with long and overly technical or speculative information on GIFs was also raised, for example:

I don't think that any details about what incidental findings might show should be in consent documents because it is going to get exhaustive and one of the things we already have a problem within the consent problem [process?] is that they're too long and they're too full of stuff. No really, honestly, asking anyone to plow through one of these 15-page documents is a little bit ridiculous even if it's at an eighth grade level. (Participant #19)

Discussion

IGRRs and GIFs are part of a spectrum of individual research results that may surface over the course of conducting genomic research. Issues surrounding the management of GIFs and IGRRs continue to be examined (Beskow & Burke, 2010; Dressler, 2009; Ramoni et al., 2011; S. M. Wolf, 2011). Questions also surround the feasibility, content, and quality of informed consent for genomic research (Caulfield et al., 2008; Henderson, 2011; Sharp, 2011). Not all genomic research studies will require informed consent processes that explicitly address the prospect of IGRRs (Fabsitz et al., 2010). Among those that will, efforts are needed to determine how IGRR and GIF prospects can be appropriately and practicably addressed. This research study was exploratory and intended to provide a preliminary understanding of IRB Chair pe rspectives on addressing the prospect of GIFs in informed consent processes. The results of the study point to several insights warranting additional discussion and research.

Recommendations for Future Discussion and Research

overlap between IRB chair perspectives and national-level guidelines

IRBs review research proposals to assure that they adhere to federal regulations and ethical standards for the protection of study participants’ rights and welfare (Abbott & Grady, 2011). Currently, there is the capacity to assess only how closely IRB perspectives and practices with respect to GIFs and informed consent overlap with national-level guidelines on IGRRs and informed consent, including NHLBI guidelines (Bookman et al., 2006; Fabsitz et al., 2010). For example, there is overlap in the suggestion by this study's IRB Chairs and NHLBI (Bookman et al., 2006; Fabsitz et al., 2010) recommendations that the potential relevance of GIF/IGRR disclosure be explained, including the potential for harm, and that research participants be given the opportunity to opt in or out of receiving GIFs and IGRRs. If supported by more generalizable research on IRB Chair and other stakeholder perspectives, this overlap presents a basis for discussing how informed consent processes can best operationalize these recommendations.

providing the opportunity to opt in/out of receiving GIFs

The view by IRB Chairs in this study that research participants should be given an opt in/out opportunity with respect to GIFs is consistent with research suggesting that individuals value having control over disclosure decisions, as well as the option of being able to change their choices with respect to the return of research results (Murphy et al., 2008; Simon et al., 2011). The potential for changing choices suggests the need for periodic reaffirmation of participant preference, which may be integrated with relatively minimal cost and effort in studies aiming to recontact research participants for other purposes such as requesting additional procedures or follow-up study participation. However, for studies not planning such recontacts, the cost, timing, and effort it may take to recontact participants for purposes to reaffirm GIF notification preferences may be significant. How possible preference changes can or should be identified, by whom, and what implications they may have for the maintenance of valid informed consent warrants further investigation.

possible perceived need to override participant preference

A particularly contentious issue is suggested by IRB Chairs who foresee special circumstances that may warrant overriding an individual's GIF disclosure preferences. Factors such as the probability or magnitude of harm associated with GIF disclosure, along with the seriousness of the GIF condition, may be factors weighing into these special circumstances. Current IGRR disclosure guidelines such as those put forth by the NHLBI do not address this contingency. Yet, there may be a tension in IRB Chair perspectives on GIF disclosure preferences, between the perceived need to do no harm and to respect personal autonomy. As Pelias has commented, this tension pervades the question of who decides whether research results should or should not be disclosed to research participants (Pelias, 2005). Studies able to randomly recruit larger samples of IRB Chairs and compare IRB Chair perspectives on the perceived permissibility of overriding participant disclosure preferences could shed useful information on this contentious issue.

addressing risks or harms of result disclosure

Both NHLBI and IRB Chair recommendations call for the addressing of potential risks or harms associated with IGGR and GIF disclosures respectively. However, while the NHLBI guidelines provide a relatively unproblematic account of the possible harms that need to be addressed (Bookman et al., 2006; Fabsitz et al., 2010), IRB Chairs voiced concerns about the potential to overstate the risks of possible GIF disclosure, and talked of the difficulty of documenting the potential for harm with regard to GIFs, given the unpredictability of their occurrence and significance. Future efforts to refine NHLBI and other guidelines on IGRRs and informed consent may want to consider taking these concerns into account.

potential burden of information

NHLBI guidelines are relatively silent on the burden (i.e., added length and complexity) of information that may accompany informed consent efforts to explain IGRR and GIF prospects. Many studies document the difficulties of conveying informed consent information in an accurate, clear, and easy-to-understand manner (Joffe et al., 2001; Lidz et al., 1983; Simon & Kodish, 2005; Simon et al., 2006). Our study findings suggest that IRB Chairs may be concerned about lengthening and complicating informed consent processes through the inclusion of GIF-related information. Members of the public have voiced concerns that informed consent processes for genetic/genomic research studies may be overly long, confusing, and time consuming, and may cause people to shy away from participation in important research (Simon et al., 2011). IRB Chairs may need to be engaged in efforts to ensure that informed consent guidelines or policies take into account the potential detriments posed by lengthening and complicating consent processes through GIF and IGRR information. Recent efforts to create simplified informed consent documents for genetic and genomic research may assist in this respect (Beskow et al., 2010).

There is a related need to examine how public literacy, including scientific, health, and/or genetic literacy, should be factored into the crafting of informed consent language on GIFs. Low literacy is a barrier in efforts to obtain informative and valid consent for research (Raich, Plomer, & Coyne, 2001). For many laypeople, basic genetic concepts are frequently confusing and frustrating to grasp (Lanie et al., 2004). Work is needed to determine how information and choices regarding GIFs can be presented to individuals across the literacy spectrum and in a manner sensitive to the intersections of individual literacy, education, culture, and community.

distinguishing GIF and IGRR prospects

Work is needed to determine if current national-level guidelines and local IRB practices on informed consent should distinguish the prospect of GIFs from IGRRs more generally. IRB Chairs in our study were asked about IFs and GIFs, yet it is unclear to what extent they were alluding more broadly to IGRRs. Whether informed consent process should distinguish between GIFs and IGRRs, including with respect to the opportunity for research participants to opt in or out of GIF versus IGRR disclosure, is also unclear, yet has ethical and practical implications for informed consent. Scholars (e.g., Parker, 2008) have argued for a separate and nuanced treatment of incidental findings in informed consent; however, whether this view is supported among IRB Chairs and architects of national-level guidelines still needs to be established.

Study Limitations

Although we reached data saturation and included Chairs from different disciplinary backgrounds and institutions (e.g., degree and non-degree granting), our results may not be representative of IRB Chair perspectives generally. The sample was purposive and not random. We were unable to determine if IRB Chairs at institutions serving traditionally underrepresented populations may hold somewhat different views on informed consent, GIFs, and related issues such as disclosure choice and literacy, when compared to Chairs at other institutions. Our interview questions were also focused on genetic and genomic research in general, and did not address specific types of genomic research. This phrasing was intentional as we presumed that IRB Chairs would likely not be as familiar as other health researchers and clinical professionals with GWAS, whole genome sequencing (WGS), and other genetic and genomic test methods (see, for example, Downing et al., in preparation). IRB interviewees responded to our interview guide questions based on their individual conceptions, rather than a common definition of GIFs, which we did not provide. Questions were limited to IFs and GIFs, and did not include IGRRs more generally. Conclusions, therefore, cannot be drawn about the extent to which Chair responses were GIF-specific.

Finally, while our larger study included perspectives of other stakeholder groups, including genomic researchers (Williams et al., in press), this study does not take into account the perspectives of researchers, members of the public, research sponsors, and research participants with respect to informed consent and GIFs. As scholars have illustrated, the perspectives of these and other groups on research-result issues are important to consider (Christensen et al., 2011; Heaney et al., 2010; Meacham et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2008). Work is needed to determine how IRB Chair perspectives on GIFs and informed consent compare to other stakeholder perspectives.

Educational Implications

Despite the relative novelty of many of the issues surrounding GIFs, IRB Chairs in our study demonstrated some knowledge and awareness of these issues. Most were able to identify several differences between IFs and GIFs. Close to one third of Chairs reported experience encountering IFs more generally; this experience may serve as a useful basis for these Chairs to help educate and be further educated on the prospect of GIFs. If IRB Chairs more generally view GIFs as distinctive from IFs, then awareness of this distinction may serve as a useful starting point for engaging IRB Chairs in the kind of researcher-IRB collaboration efforts being recommended by current guidelines (Fabsitz et al., 2010). For Chairs who anticipate that GIF issues will increasingly affect their IRB reviews and who may not be familiar with the NHLBI and other guidelines on IGRRs, exposure to these guidelines and venues at which they are frequently discussed (e.g., PRMI&R) may be beneficial. At the same time, IRB Chairs and other IRB professionals should be invited to participate in educational and policy-oriented discussions on GIFs and informed consent. Their unique position and responsibilities in relation to local oversight of research with human participants, as well as the insights some Chair researchers can bring to the table, may be invaluable in refining GIF and IGRR guidelines on informed consent. One possible outcome of these efforts may be an approach, or multiple approaches, to local informed consent policy and practice in which the issues surrounding GIF prospects are clearly explicated, transparent, and mindful of the challenges raised by the prospect of these incidental phenomena arising in genomic research.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by an American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) grant from the National Human Genome Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (RC1HG005786). Support was also provided by Grant #TL1RR024981 (training support for DB) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a part of the NIH. The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors also thank the University of Northern Iowa Center for Social and Behavioral Research for assistance in data collection.

Biography

Christian M. Simon is Associate Professor of Bioethics and Humanities in the Department of Internal Medicine and the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa. His primary research interest is the ethics of conducting clinical and translational research.

Janet K. Williams is the Kelting Professor of Nursing and Chair of the Behavioral and Social Science IRB at the University of Iowa. Her primary research interests are the psychosocial impact of genetic and genomic knowledge on individuals and families.

Laura Shinkunas is a Research Associate in the Program in Bioethics and Humanities in the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa. Her primary interest is research ethics.

Debra Brandt is a PhD student at the University of Iowa College of Nursing. Her areas of interest are clinical and research ethics.

Sandra Daack-Hirsch is Assistant Professor in the College of Nursing at the University of Iowa. She conducts research on communication and interpretation of genomic information in clinical, research, and community populations.

Martha Driessnack is Assistant Professor in the College of Nursing at the University of Iowa. Her research interests focus on issues surrounding the inclusion of children in research.

References

- Abbott L, Grady C. A systematic review of the empirical literature evaluating IRBs: What we know and what we still need to learn. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2011;6(1):3–19. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apold VS, Downie J. Bad news about bad news: The disclosure of risks to insurability in research consent processes. Accountability in Research. 2011;18(1):31–44. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2011.542681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JS, Khoury MJ, Evans JP. Deploying whole genome sequencing in clinical practice and public health: Meeting the challenge one bin at a time. Genetics in Medicine. 2011;13(6):499–504. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318220aaba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beskow LM, Burke W. Offering individual genetic research results: Context matters. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2(38):1–5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beskow LM, Friedman JY, Hardy NC, Lin L, Weinfurt KP. Simplifying informed consent for biorepositories: Stakeholder perspectives. Genetics in Medicine. 2010;12(9):567–572. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ead64d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookman EB, Langehorne AA, Eckfeldt JH, Glass KC, Jarvik GP, Klag M, et al. Reporting genetic results in research studies: Summary and recommendations of an NHLBI working group. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A. 2006;140(10):1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke W, Atkins D, Gwinn M, Guttmacher A, Haddow J, Lau J, et al. Genetic test evaluation: Information needs of clinicians, policy makers, and the public. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;156(4):311–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield T, McGuire AL, Cho M, Buchanan JA, Burgess MM, Danilczyk U, et al. Research ethics recommendations for whole-genome research: Consensus statement. PLoS Biology. 2008;6(3):e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MK. Understanding incidental findings in the context of genetics and genomics. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):280–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KD, Roberts JS, Shalowitz DI, Everett JN, Kim SYH, Raskin L, Gruber SB. Disclosing individual CDKN2A research results to melanoma survivors: Interest, impact, and demands on researchers. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20(3):522–529. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzin-Frankel J. Human genome 10th anniversary: What would you do? Science. 2011;331(6018):662–665. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6018.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing NR, Williams JK, Daack-Hirsch S, Driessnack M, Simon C. Managing genomic incidental findings in the clinical setting. in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dressler LG. Disclosure of research results from cancer genomic studies: State of the science. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(13):4270–4276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabsitz RR, McGuire A, Sharp RR, Puggal M, Beskow LM, Biesecker LG, et al. Ethical and practical guidelines for reporting genetic research results to study participants: Updated guidelines from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Circulatory and Cardiovascular Genetics. 2010;3(6):574–580. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gikonyo C, Bejon P, Marsh V, Molyneux S. Taking social relationships seriously: Lessons learned from the informed consent practices of a vaccine trial on the Kenyan Coast. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(5):708–720. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney C, Tindall G, Lucas J, Haga SB. Researcher practices on returning genetic research results. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 2010;14(6):821–827. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson GE. Is informed consent broken? American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2011;342(4):267–272. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31822a6c47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent in cancer clinical trials: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358(9295):1772–1777. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AD, Bhimavarapu A, Benjamin EJ, Fox C, Levy D, Jarvik GP, et al. CLIA-tested genetic variants on commercial SNP arrays: Potential for incidental findings in genome-wide association studies. Genetics in Medicine. 2010;12(6):355–363. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e1e2a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AD, O'Donnell CJ. An open access database of genome-wide association results. BMC Medical Genetics. 2009;10(6) doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane MA. Institutional review board approaches to the incidental findings problem. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):352–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozanczyn C, Collins K, Fernandez CV. Offering results to research subjects: U.S. institutional r eview board policy. Accountability in Research. 2007;14(4):255–267. doi: 10.1080/08989620701670179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanie AD, Jayaratne TE, Sheldon JP, Kardia SL, Anderson ES, Feldbaum M, et al. Exploring the public understanding of basic genetic concepts. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2004;13(4):305–320. doi: 10.1023/b:jogc.0000035524.66944.6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidz CW, Meisel A, Osterweis M, Holden JL, Marx JH, Munetz MR. Barriers to informed consent. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1983;99(4):539. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-4-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire AL, Beskow LM. Informed consent in genomics and genetic research. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 2010;11:361–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacham MC, Starks H, Burke W, Edwards K. Researcher perspectives on disclosure of incidental findings in genetic research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2010;5(3):31–41. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.3.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FG, Mello MM, Joffe S. Incidental findings in human subjects research: What do investigators owe research participants? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J, Scott J, Kaufman D, Geller G, LeRoy L, Hudson K. Public expectations for return of results from large-cohort genetic research. American Journal of Bioethics. 2008;8(11):36–43. doi: 10.1080/15265160802513093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NVivo qualitative data analysis software . Version 8. QSR International Pty Ltd.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Biorepositiories and Biospecimen Research Workshop on release of research results to participants in biospecimen studies. 2010a Retrieved from http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/global/pdfs/NCI_Return_Research_Results_Summary_Final-508.pdf.

- Office of Biorepositories and Biospecimen Research NCI best practices for biospecimen resources. 2010b Retrieved from http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/global/pdfs/Revised%20NCI%20Best%20Practices_public%20comment.pdf.

- Parker LS. The future of incidental findings: Should they be viewed as benefits? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):341–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelias MK. Research in human genetics: The tension between doing no harm and personal autonomy. Clinical Genetics. 2005;67(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raich PC, Plomer KD, Coyne CA. Literacy, comprehension, and informed consent in clinical research. Cancer Investigation. 2001;19(4):437–445. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100103137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramoni R, McGuire A, Morley D, Joffe S. Attitudes and practices of genome investigators regarding return of individual genetic test results; 2011 ELSI Congress; National Human Genome Research Institute, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. April 12–14.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rotimi CN, Marshall PA. Tailoring the process of informed consent in genetic and genomic research. Genome Medicine. 2010;2(3):20. doi: 10.1186/gm141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp RR. Downsizing genomic medicine: Approaching the ethical complexity of whole-genome sequencing by starting small. Genetics in Medicine. 2011;13(3):191–194. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31820f603f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CM, Kodish ED. Step into my zapatos, Doc: Understanding and reducing communication disparities in the multicultural informed consent setting. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2005;48(1 Suppl.):S123–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CM, L'Heureux J, Murray JC, Winokur P, Weiner G, Newbury E, et al. Active choice but not too active: Public perspectives on biobank consent models. Genetics in Medicine. 2011;13(9):821–831. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821d2f88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CM, Zyzanski SJ, Durand E, Jimenez X, Kodish ED. Interpreter accuracy and informed consent among Spanish-speaking families with cancer. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(5):509–522. doi: 10.1080/10810730600752043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovino SA. Incidental findings: A common law approach. Accountability in Research. 2008;15(4):242–261. doi: 10.1080/08989620802388705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health & Office for Protection from Research Risks Protection of Human Subjects, 45 C.F.R. § 46.116. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.htm.

- Williams JK, Daack-Hirsch S, Driessnack M, Downing N, Shinkunas L, Brandt D, et al. Researcher and IRB chair perspectives on incidental findings in genomic research. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 2012 doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2011.0248. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winickoff DE, Winickoff RN. The charitable trust as a model for genomic biobanks. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(12):1180–1184. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb030036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf LE, Catania JA, Dolcini MM, Pollack LM, Lo B. IRB chairs’ perspectives on genomics research involving stored biological materials: Ethical concerns and proposed solutions. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2008;3(4):99–111. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.4.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SM. Introduction: The challenge of incidental findings. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):216–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SM. New developments in governance and oversight [plenary]; Presentation exploring the ELSI universe: Ethical, legal, & social implications; National Human Genome Research Institute, Chapel Hill, NC.. April 12–14.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, Kahn JP, Cho MK, Clayton EW, et al. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: Analysis and recommendations. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):219–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]