Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes that largely contribute to the efficacy of therapeutic strategies like allogenic stem cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and application of Rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family member GITR ligand (GITRL) is frequently expressed on leukemia cells in AML and CLL and impairs the reactivity of NK cells which express GITR and upregulate its expression following activation. We developed a strategy to reinforce NK anti-leukemia reactivity by combining disruption of GITR–GITRL interaction with targeting leukemia cells for NK antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) using GITR-Ig fusion proteins with modified Fc moieties. Neutralization of leukemia-expressed GITRL by the GITR domain enhanced cytotoxicity and cytokine production of NK cells depending on activation state with NK reactivity being further largely dependent on the engineered affinity of the fusion proteins to the Fc receptor. Compared with wild-type GITR-Ig, treatment of primary AML and CLL cells with mutants containing a S239D/I332E modification potently increased cytotoxicity, degranulation, and cytokine production of NK cells in a target-antigen–dependent manner with additive effects being observed with CLL cells upon parallel exposure to Rituximab. Fc-optimized GITR-Ig may thus constitute an attractive means for immunotherapy of leukemia that warrants clinical evaluation.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes and components of innate immunity.1 Their reactivity is guided by the principles of “missing-self” and “induced-self” recognition, which implies that NK cells kill target cells with low/absent expression of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I (“missing-self”) and/or stress-induced expression of ligands for activating NK receptors (“induced-self”).2 The particular role of NK cells in the immunosurveillance of leukemia is highlighted, among others, by results of haploidentical stem cell transplantation, wherein recipient's leukemia cells fail to inhibit donor NK cells due to KIR disparity, which is associated with powerful graft versus leukemia effects and better clinical outcome.3,4 Moreover, NK cells may also participate in controlling leukemia in an autologous setting as suggested, e.g., by data that NK cell counts and activity are reduced in leukemia patients, that survival of leukemia patients is associated with activity of their NK cells and that expression of HLA class I molecules is downregulated on leukemia cells.5,6,7,8,9

Notably, a whole variety of immunoregulatory molecules far beyond the receptors involved in missing- and induced-self recognition influence NK reactivity.2,10 This comprises the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family member GITR (TNFRSF18), which potently influences immune responses in general and anti-tumor immunity in particular. Initially considered to be a major inhibitor of regulatory T-cell activity, the GITR-GITR ligand (GITRL) molecule system is meanwhile known to affect multiple different cell types and to modulate a great variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions.11,12,13 In mouse tumor models, GITR stimulation was reported to improve animal survival and even lead to the eradication of tumors, which was mainly attributed to T-cell immunity.14,15,16,17,18,19 However, evidence that GITR mediates different effects in mice and men is accumulating,13,20,21 and we and others recently demonstrated that GITR expressed on human NK cells inhibits their effector functions, resulting, among others, in impaired reactivity against GITRL-expressing AML and CLL cells.22,23,24,25

Another immunoreceptor that potently influences NK cell reactivity is the Fc receptor IIIa (FcγRIIIa, CD16), which mediates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). Induction of ADCC largely contributes to the effectiveness of clinically used anti-tumor antibodies like Rituximab, which meanwhile is an essential component in treatment of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.26 However, the efficacy of Rituximab and other available anti-tumor antibodies has its limitations: some patients do not respond at all, others for a limited time only.27 In CLL, the ability of NK cells to target malignant cells upon application of Rituximab is compromised,28,29,30,31 and NK inhibitory GITRL expression by leukemic cells contributes to the same.25 Multiple efforts are presently made to enhance the efficacy of Rituximab and other anti-tumor antibodies, and modifications of their Fc parts to enhance induction of anti-tumor immunity is an intriguing approach.32,33 Several Fc-engineered anti-lymphoma antibodies mediating markedly enhanced ADCC are presently in preclinical and early clinical development.34,35,36,37 Another major problem is that in many malignancies including AML no anti-tumor antibodies that stimulate NK reactivity are available as of yet.

Since (i) GITRL is expressed by AML and CLL cells in a high proportion of cases and inhibits direct and Rituximab-induced anti-leukemia reactivity of NK cells,24,25 and (ii) techniques to increase the affinity of Fc parts to CD16 resulting in enhanced NK cell reactivity are available,38 we here generated Fc-engineered GITR-Ig fusion proteins capable to prevent NK cell inhibition by blocking GITR–GITRL interaction while at the same time targeting the leukemia cells for NK cell reactivity. These compounds were pre-clinically characterized, among others by employing AML and CLL cells of patients in functional analyses with allogenic and autologous NK cells to avoid misinterpretations caused by species-specific particularities of the GITR-GITRL molecule system.

Results

Generation of Fc-engineered GITR-Ig fusion proteins

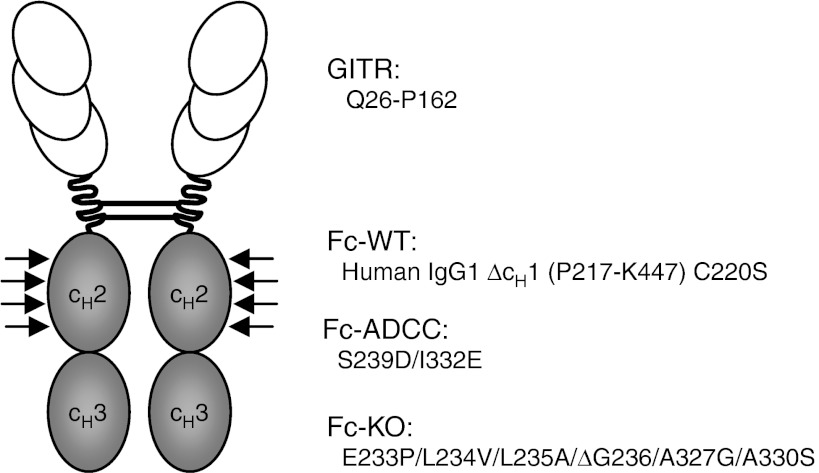

GITRL, which is frequently expressed by AML and CLL cells, impairs NK cell anti-tumor reactivity.23,24,25 To reinforce NK reactivity, we here developed a strategy combining neutralization of the inhibitory effects of GITRL with induction of ADCC. To this end, we generated fusion proteins consisting of the extracellular domain of GITR (Q26-P162) fused to the Fc part of human IgG1 (P217-K447) lacking the cH1 domain and containing a Cys to Ser substitution at position 220 (GITR-Fc-WT). To obtain GITR-Ig fusion proteins with enhanced affinity to CD16 and thus improved ability to induce ADCC (GITR-Fc-ADCC), we modified the Fc part by the amino acid substitutions S239D/I332E as previously described.38 Moreover, we engineered GITR-Ig with Fc parts containing E233P/L234V/L235A/ΔG236/A327G/A330S amino acid modifications (GITR-Fc-KO) resulting in abrogated affinity to CD16,39 which served to delineate the specific contribution of GITR–GITRL interaction, or rather its disruption, in functional analyses with NK cells (Figure 1). The different fusion proteins and also Fc-specific controls were then produced and purified as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the GITR-Ig fusion proteins. GITR-Ig fusion proteins were generated as dimeric constructs containing the extracellular domain of the GITR receptor (Q26-P162) and a human Fc tail (P217-K447 with C220S) with either the wild-type amino acid sequence or with several modifications (indicated by arrows) to enhance or to knockout its recognition by Fc receptors.

Binding characteristics of the GITR-Ig fusion proteins

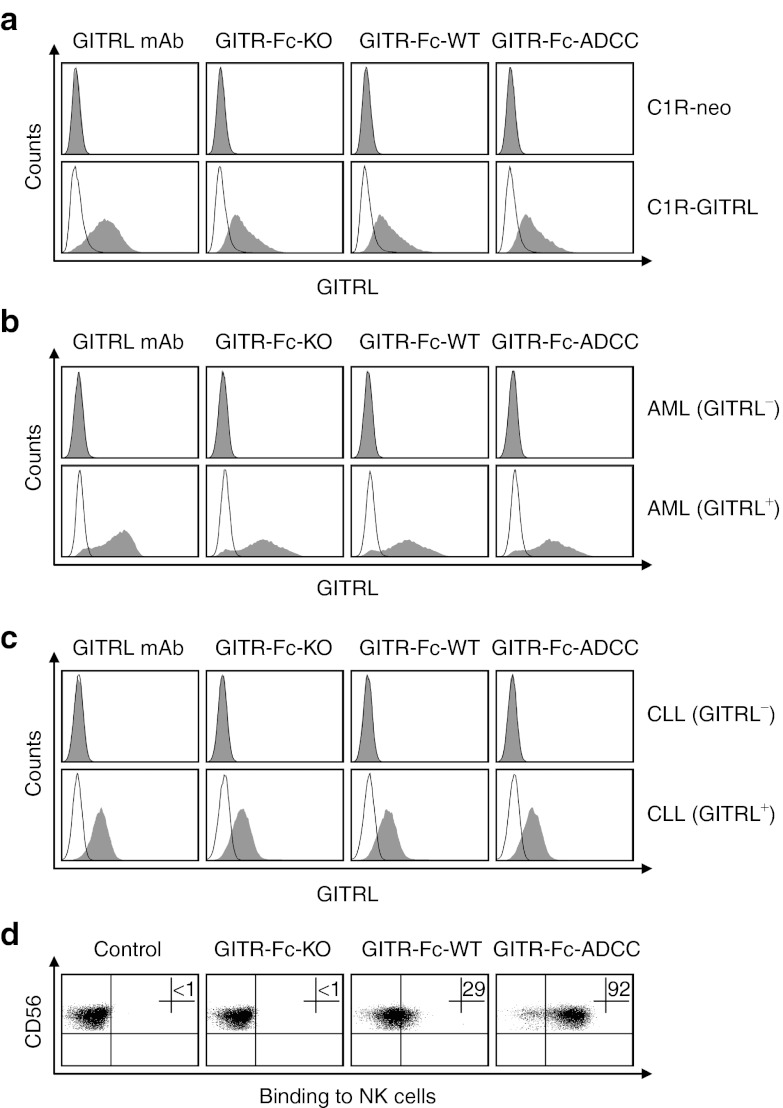

To characterize the binding of the different fusion proteins to GITRL, we first employed GITRL transfectants (C1R-GITRL) and control cells (C1R-neo). Expression or lack of GITRL on the cell surface was confirmed by analyses with GITRL-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb). No binding of the GITR-Ig fusion proteins was observed with C1R-neo cells, whereas all three fusion proteins comparably bound to the GITRL transfectants (Figure 2a). Moreover, the GITR-Ig fusion proteins specifically bound to primary AML and CLL cells that displayed GITRL expression in parallel analyses with GITRL mAb, but not to GITRL-negative patient cells. Again, all three fusion proteins comparably bound to GITRL as revealed by utilizing Fc controls containing the respective modification of the different fusion proteins (Figure 2b,c). Notably, substantially more pronounced binding of GITR-Fc fusion protein was observed with malignant cells as compared with healthy B cells, monocytes, dendritic cells (DC) or endothelial cells that reportedly also express GITRL (Supplementary Figure S1). Next, we characterized the binding of the modified Fc parts of the different fusion proteins to CD16 on polyclonal NK (pNK) cells. No binding of the GITR-Fc-KO to pNK cells, which do not express GITRL,24 was observed, which confirmed the abrogated affinity of its Fc part to CD16. In contrast, GITR-Fc-WT clearly bound to pNK cells, and GITR-Fc-ADCC displayed substantially increased binding due to the modifications in its Fc part (Figure 2d). Similar results were obtained when experiments were performed with resting NK cells among freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) of healthy donors (data not shown). Together, these data demonstrate that our GITR-Ig fusion proteins specifically recognize GITRL that is highly expressed by primary AML and CLL cells and that binding to CD16 on NK cells is dependent on, and in case of GITR-Fc-ADCC substantially enhanced by, the Fc modifications.

Figure 2.

Binding characteristics of the Fc-engineered GITR-Ig fusion proteins. (a–c) Specific binding of the indicated GITR-Ig fusion proteins to surface-expressed GITRL was confirmed by FACS after determination of GITRL positivity using GITRL mAb and isotype control as described in the Materials and Methods section. (a) GITRL transfectants (C1R-GITRL) and control cells (C1R-neo); (b) primary GITRL-positive and -negative AML and (c) primary GITRL-positive and -negative CLL cells. Shaded peaks, specific mAb or fusion proteins (10 µg/ml each); open peaks, respective controls. (d) NK cells were incubated with the different GITR-Ig fusion proteins followed by a secondary PE-conjugate and analysis by FACS to unravel binding of the Fc parts to CD16. Data of one representative experiment each out of at least five with similar results are shown. AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NK, natural killer cell.

Modulation of NK cell reactivity by the engineered Fc parts of the GITR-Ig fusion proteins

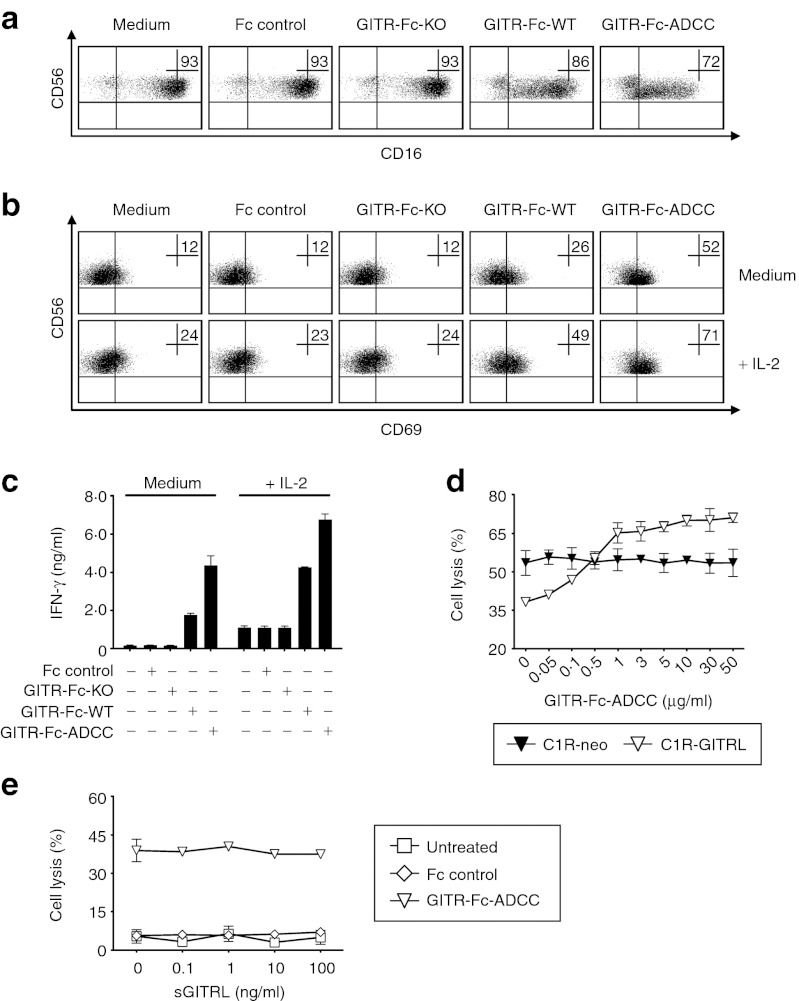

Next, we determined the capacity of the modified Fc parts of the different GITR-Ig fusion proteins to trigger CD16 and thereby alter the reactivity of NK cells. To exclude a potential interference of other immunoregulatory molecules expressed by target cells, an assay system was implemented in which the GITR-Ig fusion proteins were bound to GITR mAb immobilized on plastic. In line with the described correlation of binding of Fc parts with downregulation of CD16 surface expression and the varying binding affinity of the modified IgG1 Fc parts,38,39,40 we observed a clear reduction of CD16 on pNK cells with GITR-Fc-WT. This was by far exceeded by GITR-Fc-ADCC, whereas no effects were observed with GITR-Fc-KO (Figure 3a). Moreover, GITR-Fc-WT induced pNK cell activation as revealed by upregulation of the activation marker CD69 and also stimulated the release of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which constitutes a second major effector mechanism by which NK cells contribute to anti-tumor immunity.1,41 GITR-Fc-KO did not influence pNK reactivity in these analyses, while GITR-Fc-ADCC caused substantially pronounced activation and cytokine production as compared with GITR-Fc-WT. Additional exposure of pNK cells to interleukin (IL)-2 generally increased their reactivity without altering the differential effects of the three fusion proteins (Figure 3b,c). These results confirmed the capacity of GITR-Fc-ADCC to potently induce NK reactivity due to the modifications in its Fc part.

Figure 3.

Modulation of NK cell reactivity by the GITR-Fc constructs. (a–c) Twenty-four well plates were coated with GITR mAb and blocked by addition of 10% FCS-PBS followed by addition of GITR-Ig fusion proteins or Fc controls (10 µg/ml each) and washing. Subsequently, pNK cells were added and cultured for 24 hours in the presence or absence of 100 U/ml IL-2 (+ IL-2) as indicated. (a) Downregulation of CD16 expression and (b) upregulation of the activation marker CD69 was analyzed by FACS; the percentage of positive NK cells is indicated. (c) Supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ levels by ELISA. (d) Lysis of C1R-GITRL and C1R-neo by pNK cells (E:T ratio, 10:1) upon exposure to the indicated concentrations of GITR-Fc-ADCC was determined by 2-hour europium release assays. (e) C1R-GITRL and pNK cells (E:T ratio, 10:1) were cultured with or without GITR-Fc-ADCC or Fc control (10 µg/ml each) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of sGITRL. Cytotoxicity was determined by 2-hour europium release assay. One representative experiment each of a total of at least three with similar results is shown. FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; E:T, Effector:target; FCS, fetal calf serum; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NK, natural killer cell; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Next, we performed dose titrations of GITR-Fc-ADCC in cultures of pNK cells with GITRL transfectants and control cells and studied its effects on target cell lysis. In line with findings by us and others that GITR–GITRL interaction inhibits NK reactivity,22,23,24,25 GITRL expression on target cells resulted in substantially decreased pNK cytotoxicity. Already in concentrations as low as 0.5 µg/ml, the GITR-Fc-ADCC fusion protein compensated for the GITRL-induced suppression of NK reactivity and in higher concentrations clearly increased lysis of C1R-GITRL cells with maximal effects occurring at about 10 µg/ml. Notably, GITR-Fc-ADCC did not influence lysis of the GITRL-negative control cells, thereby confirming that stimulation of NK reactivity required binding of our construct to surface-expressed GITRL (Figure 3d).

As sera of patients with cancer including AML frequently contain a soluble form of GITRL (sGITRL),24,42 we next determined whether the capacity of our construct to stimulate NK reactivity at 10 µg/ml, the concentration chosen for further experiments, was affected by sGITRL. No relevant reduction of GITR-Fc-ADCC–induced pNK cell cytotoxicity by sGITRL up to concentrations of 100 ng/ml (which is about tenfold more than the levels found in patient sera) was observed. This can be explained by the clear excess of the fusion protein in these experiments with the employed concentration notably being in a range achieved with other, clinically already used fusion proteins upon recommended dosing (Figure 3e).43

Modulation of NK reactivity against primary AML and CLL cells by the GITR-Ig fusion proteins

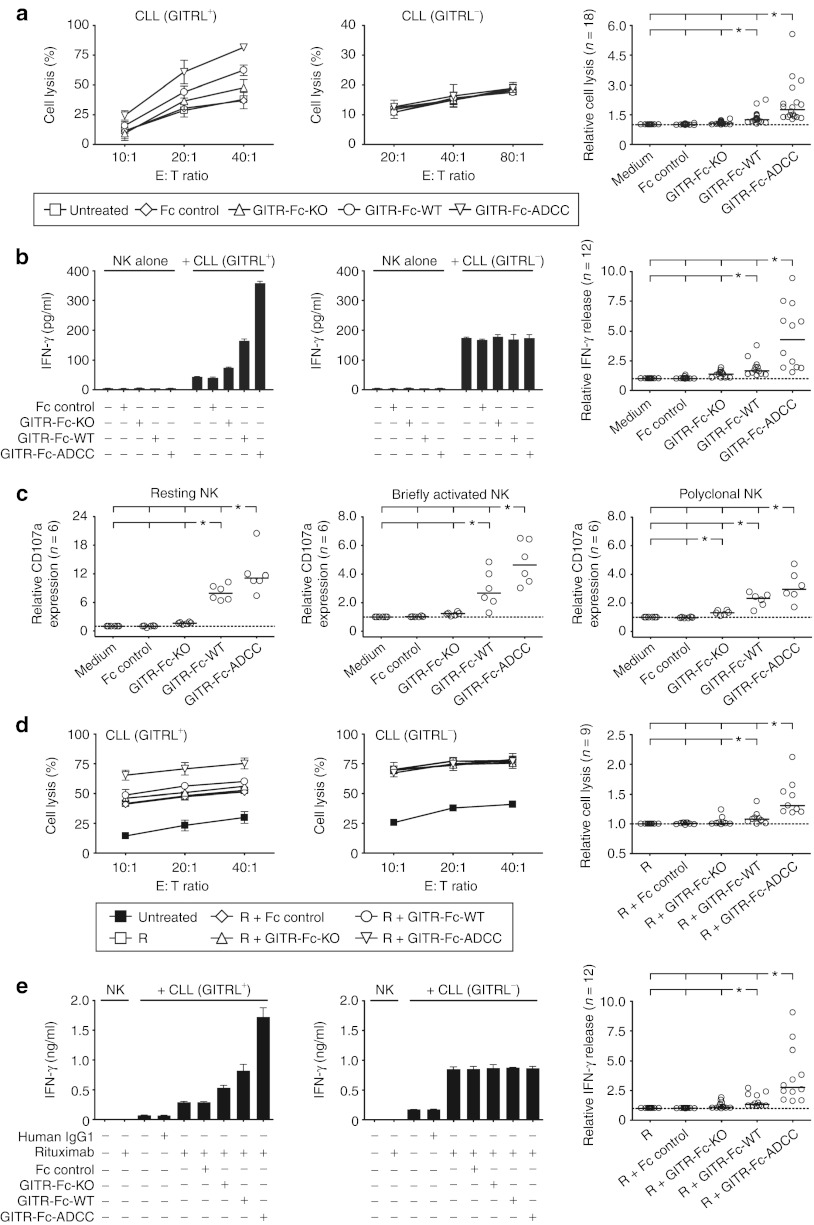

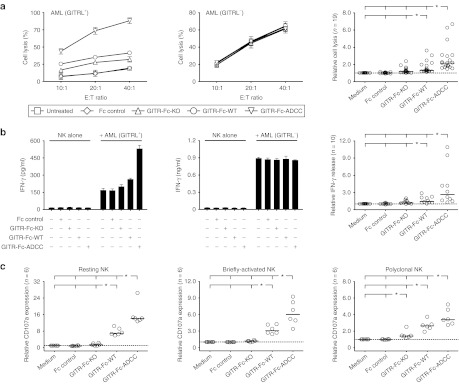

Next, we determined the capacity of our fusion proteins to stimulate the reactivity of NK cells against GITRL-expressing AML patient cells. GITR-Fc-KO increased the cytotoxicity of allogenic pNK cells due to disruption of GITR–GITRL interaction, whereas the Fc controls did not influence AML cell lysis. Compared with the effects of GITR-Fc-KO, NK reactivity was further increased with GITR-Fc-WT and potently enhanced upon treatment with GITR-Fc-ADCC (Figure 4a). Similar results were obtained with regard to the effects of the different fusion proteins on IFN-γ production of pNK cells (Figure 4b). Next, we analyzed how our constructs affected the reactivity of resting and briefly activated NK cells as compared with NK cells that were exposed to activating cytokines for longer time periods like the pNK cells. To avoid potential artifacts due to NK cell isolation, we employed PBMC of healthy donors that were either used directly or were only exposed to IL-2 for 12 hours and thus express only low levels of GITR.22 The GITR-Fc-WT significantly induced CD107a expression, a surrogate marker for granule mobilization, on resting and briefly activated NK cells as well as pNK cells, and these effects were by far exceeded by GITR-Fc-ADCC. Differential effects were observed with GITR-Fc-KO: while reactivity of pNK cells was significantly increased alike in the analyses of cytotoxicity and cytokine production, no significant effects were observed with resting/briefly activated NK cells, which most likely is attributable to the low GITR expression on the latter (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Induction of NK reactivity against primary AML cells by GITR-Ig fusion proteins. Leukemia cells of AML patients (>80% blast count) were cultured with PBMC or pNK cells as indicated in the presence or absence of GITR-Ig fusion proteins or Fc controls (10 µg/ml each). (a) Cytotoxicity of pNK cells was determined by 2-hour europium release assays. (b) IFN-γ levels released by pNK cells into supernatants were analyzed after 24 hours by ELISA. Exemplary results using GITRL-positive (left) and -negative (middle) AML cells as well as combined results obtained in the indicated number (n) of independent experiments with GITRL-positive patient cells (right) are shown. (c) Granule mobilization on resting (left panel) and briefly activated (12 hours exposure to 50 U/ml IL-2, middle panel) NK cells among PBMC of healthy donors as well as pNK cells (right panel) was analyzed by FACS for CD107a after 3 hours of culture. For combined analysis, results obtained with untreated target cells were set to one (dotted line) in each individual data set to enable statistical analysis. *Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test). AML, acute myeloid leukemia; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; NK, natural killer cell; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

When we employed primary GITRL-expressing CLL cells as targets in analyses of cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production, again already blocking GITR–GITRL interaction without inducing ADCC as achieved by GITR-Fc-KO enhanced pNK cell reactivity. Addition of GITR-Fc-WT further increased pNK cell cytotoxicity and cytokine release as compared with the effects of GITR-Fc-KO, and this was again by far exceeded by the GITR-Fc-ADCC (Figure 5a,b). When we studied the effects of our fusion proteins on degranulation using resting/briefly activated versus pNK cells with CLL cells as targets, we again found a clear induction of NK reactivity by GITR-Fc-WT and GITR-Fc-ADCC but not by GITR-Fc-KO (Figure 5c). Next, we compared the efficacy of GITR-Fc-ADCC to stimulate NK cell reactivity against CLL cells with that of Rituximab, which reportedly mediates its therapeutic effects in great part by induction of ADCC.26 Notably, despite the by far higher expression levels of CD20 as compared with GITRL on the CLL cells the capacity of GITR-Fc-ADCC to stimulate NK reactivity was comparable to that of Rituximab as revealed by analyses of cytotoxicity, IFN-γ production, and granule mobilization (Supplementary Figure S2). Combined treatment of CLL cells with GITR-Ig fusion proteins and Rituximab stimulated NK cell reactivity beyond the effects of Rituximab alone when GITRL-positive primary CLL cells were used as targets. In these analyses, the effects of GITR-Fc-ADCC again by far exceeded that of GITR-Fc-KO and also of the GITR-Fc-WT (Figure 5d,e). Notably, NK reactivity without treatment and also the effects of the different fusion proteins varied substantially with NK cells of different donors, but in all cases GITR-Fc-ADCC significantly enhanced NK reactivity and its effects were by far more pronounced as compared with the other fusion proteins. None of the fusion proteins altered pNK cell reactivity when GITRL-negative leukemia cells were employed as targets, which confirmed that stimulation of NK cell reactivity required binding of our constructs to surface-expressed GITRL (Figures 4 and 5). In line with the observed weak binding of our constructs, no relevant ADCC of allogenic pNK cells against DC or endothelial cells (human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC)) was observed (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 5.

Induction of NK reactivity against primary CLL cells by GITR-Ig fusion proteins. Leukemic cells of CLL patients (>80% lymphocyte count) were cultured with PBMC or pNK cells as indicated in the (a–c) absence or (d,e) presence of Rituximab (R) with or without GITR-Ig fusion proteins or Fc controls (10 µg/ml each). (a,d) Cytotoxicity of pNK cells was determined by 2-hour europium release assays. (b,e) IFN-γ levels released by pNK cells into supernatants were analyzed after 24 hours by ELISA. Exemplary results using GITRL-positive (left) and -negative (middle) CLL cells as well as combined results obtained in the indicated number (n) of independent experiments with GITRL-positive patient cells (right) are shown. (c) Granule mobilization on resting (left panel) and briefly activated (12 hours exposure to 50 U/ml IL-2, middle panel) NK cells among PBMC of healthy donors as well as pNK cells (right panel) was analyzed by FACS for CD107a after 3 hours of culture. For combined analysis, results obtained with untreated or Rituximab-treated target cells were set to one (dotted line) in each individual data set to enable statistical analysis. *Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test). CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; E:T, Effector:target; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; NK, natural killer cell; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Validation of the anti-leukemia effects of the GITR-Ig fusion proteins in the autologous system

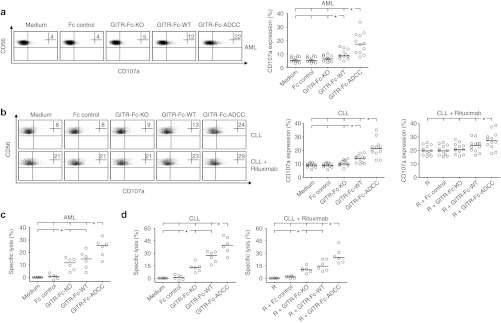

Finally, we studied the effects of the GITR-Ig fusion proteins on NK reactivity against primary AML and CLL cells in an autologous setting to mirror treatment in leukemia patients. To this end, we added our fusion proteins or Fc controls to PBMC of AML and CLL patients and analyzed the modulation of CD107a expression on NK cells. Degranulation of autologous NK cells in response to AML cells was significantly enhanced by GITR-Fc-WT. A significantly more pronounced effect was observed with GITR-Fc-ADCC, while only minor effects were observed with GITR-Fc-KO (Figure 6a). Similar results were obtained with samples of CLL patients, and degranulation was also enhanced by addition of Rituximab. Upon combined treatment with the CD20 antibody and the fusion proteins, only the combination with GITR-Fc-ADCC but not the other fusion proteins resulted in statistically significant additive effects. Notably, NK reactivity again varied among individual patients, and the effect achieved with GITR-Fc-ADCC was similar to and sometimes even exceeded that obtained upon treatment with Rituximab despite the dramatically lower surface levels of GITRL as compared with CD20 (Figure 6b and Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 6.

Reactivity of NK cells against primary AML and CLL cells upon treatment with GITR-Ig in the autologous system. (a,b) Granule mobilization of autologous NK cells within PBMC of (a) AML patients (CD56+CD3−CD33−CD34−) and (b) CLL patients (CD56+CD3−) with 50–90% content of leukemic cells was analyzed by FACS for CD107a after 3 hours of culture in the presence or absence of the indicated GITR-Ig fusion proteins or Fc controls (10 µg/ml each). In case of CLL samples, experiments were performed with and without Rituximab (R) (10 µg/ml) as indicated. Numbers in dot plots represent the percentage of CD107a-positive NK cells. Exemplary results of one experiment are shown in the upper panels. Lower panels represent combined results obtained with 12 different patients of each leukemia entity (percentages of CD107a-positive NK cells in each individual sample as well as medians of results). (c,d) PBMC of (c) AML and (d) CLL patients (both n = 6) were cultured in the presence or absence of the GITR-Ig fusion proteins or Fc controls (10 µg/ml each) for 24 hours. Where indicated, Rituximab (R) (10 µg/ml) was also added to CLL samples. Leukemia cell lysis was determined by a FACS-based assay system as described in the Materials and Methods section; PBMC of leukemia patients that had been left untreated or, in case of CLL were exposed to Rituximab only where indicated served as control. The median within each group is indicated by (:). *Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test). AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; NK, natural killer cell; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

In addition, we directly determined lysis of AML (CD33+ and/or CD34+) and CLL (CD19+CD5+) cells upon exposure of patient PBMC to the different GITR-Ig fusion proteins. In these analyses, which in contrast to experiments investigating NK cell degranulation (3 hours assay time) were performed over 24 hours, already the effect of disrupting GITR–GITRL interaction by the GITR-Fc-KO was clearly visible and resulted in significantly increased lysis of both AML and CLL cells as compared with untreated cells or controls. In the majority of experiments, lysis rates obtained upon exposure to GITR-Fc-KO were exceeded by treatment with GITR-Fc-WT, while addition of GITR-Fc-ADCC in all cases mediated significantly increased and substantially more pronounced leukemia cell lysis as compared with the other fusion proteins. With CLL samples, the effects of the fusion proteins were observed both in the presence and absence of Rituximab. Notably, the effects caused by all compounds again varied substantially with cells from different patients (Figure 6c,d). In line with the data obtained with DC and endothelial cells in the allogenic setting, no induction of lysis of B cells or monocytes within PBMC of healthy donors was observed upon exposure to the constructs (Supplementary Figure S1).

Taken together, our results demonstrate that targeting of leukemia-expressed GITRL using Fc-optimized GITR-Ig fusion proteins results in substantial enhancement of direct and, in case of CLL also Rituximab-induced NK reactivity due to both disruption of GITR–GITRL interaction and potent induction/enhancement of ADCC.

Discussion

Activity of both tumor and immune effector cells including NK cells is substantially influenced by various members of the TNF/TNF receptor family.44 The TNF receptor family member GITR is constitutively expressed by NK cells and upregulated following activation. It inhibits NK cell effector functions upon interaction with its ligand that is expressed on human tumor cells of various origins.22,23,24,25 In leukemia, substantial levels of GITRL were found to be expressed on the malignant cells of a high proportion of patients with AML and CLL (52 and 78% of cases, respectively), and application of blocking GITR antibody increased direct and, in case of CLL also Rituximab-induced NK anti-leukemia reactivity.24,25 In AML, leukemia cell-expressed GITRL may thus impair the clinical efficacy of allogenic stem cell transplantation, which relies in great part on sufficient NK cell alloreactivity.3,4,24 In CLL, available data indicate that NK cell effector functions including their ability to mediate ADCC upon application of Rituximab are compromised, and the high prevalence of GITRL positivity and its particularly high expression levels on CLL cells may contribute to the same.25,28,29,30,31 As in the meanwhile induction of ADCC is recognized as a major mechanism by which Rituximab and other anti-tumor antibodies mediate their effects,26 several strategies are presently being developed to improve the ability of antibodies to recruit Fc-receptor–bearing immune cells.32,33 Currently, three antibodies, directed to CD19, CD30, and CD40, carrying the amino acid modifications S239D and I332E (SDIE modification), and a CD20 antibody with improved low-fucose glycosylation are in early clinical development.34,35,36,37 These reagents mediate markedly enhanced ADCC, and it is hoped that their therapeutic activity is increased accordingly.

The approach to increase a Fc part's affinity to CD16 by the SDIE modification was used in our study to generate Fc-optimized GITR-Ig fusion proteins.38 With their GITR domain, these compounds block GITR–GITRL interaction thereby preventing NK inhibitory GITR signaling and, in contrast to blocking GITR antibodies, at the same time potently target GITRL-expressing leukemia cells for NK cell ADCC. GITR fusion proteins with wild-type IgG1 and Fc parts with abrogated affinity to CD16 were generated as controls. Target antigen-restricted binding of the fusion proteins was confirmed in analyses with transfectants as well as GITRL-positive and -negative primary leukemia cells. Only weak binding of our constructs to healthy hematopoietic and endothelial cells was observed, which is in line with available data on differential expression of GITRL in malignant cells compared with their healthy counterparts.25 Analyses with NK cells in the absence of target cells, thereby excluding a potential influence of other immunomodulatory surface molecules involved in NK–target cell interaction, then served to characterize the functional properties of the different Fc parts: as expected, exposure to GITR-Fc-WT induced NK cell activation as revealed by upregulated CD69 expression and induction of IFN-γ release. In agreement with their enhanced and abrogated affinity to CD16, GITR-Fc-ADCC displayed by far more pronounced effects while GITR-Fc-KO did not alter NK reactivity, and the different functional properties of the Fc moieties were mirrored by their effects on CD16 downregulation. As NK cells do not express GITRL,24 and no binding of GITR-Fc-KO to NK cells was observed, the effects of the fusion proteins on NK reactivity are thus clearly mediated via CD16. Dose titration experiments with GITR-Fc-ADCC in cocultures of pNK cells with C1R-GITRL transfectants and the respective mock controls revealed neutralization of the immunoinhibitory effects of GITRL already at 0.5 µg/ml. At concentrations above, a potent induction of target antigen-dependent cytolysis was observed with maximal effects occurring at about 10 µg/ml, a concentration easily reached in sera of patients upon recommended dosing of already clinically available fusion proteins.43 At this concentration, the effects of GITR-Fc-ADCC on NK reactivity were not altered by sGITRL, even in concentrations about tenfold exceeding that prevalent in cancer patient sera.24,42

Cocultures with primary AML and CLL cells were then employed to study the effects of the fusion proteins on NK reactivity. GITR-Fc-KO increased the anti-leukemia reactivity of NK cells depending on GITR expression levels as revealed by comparative analyses with resting/briefly activated (GITR-low) NK cells and pNK cells that are generated over longer time periods in the presence of activating stimuli and thus display substantially higher GITR levels. In contrast, GITR-Fc-WT clearly induced reactivity of resting/briefly activated NK cells and resulted in higher reactivity of pNK cell as compared with GITR-Fc-KO due to ADCC induction. Our GITR-Fc-ADCC construct always potently stimulated NK cell anti-leukemia reactivity with its effects by far exceeding that of GITR-Fc-WT due to the SDIE modification contained in its Fc part.38 When CLL cells were used as targets, the differential effects of the fusion proteins were also observed in the presence of Rituximab. Notably, the effects of GITR-Fc-ADCC on NK reactivity were similar to and in some cases even exceeded that of Rituximab despite the by far lower expression of GITRL as compared with CD20 on CLL cells, and combined treatment resulted in additive effects. As the therapeutic effects of Rituximab are in great part mediated by induction of ADCC,26 these results provide information on the therapeutic potential of our constructs and also highlight the potency of the SDIE modification to induce ADCC especially when targeting antigens expressed at relatively low levels. The potent immunostimulatory properties of our GITR-Fc-ADCC may be especially relevant when the ability of NK cells to mediate ADCC is compromised, e.g., upon ongoing immunosuppressive treatment after stem cell transplantation in AML or as reported for NK cells in CLL.7,9,24,25,31,45 In addition, GITR-Fc-ADCC may be especially well suited as therapeutic compound for combined application with adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded NK cells, as expansion usually involves the use of factors/cytokines that result in NK cell activation and thus enhanced GITR expression. Further rationale for such a combinatorial approach is derived from a recent study reporting that the ability of transferred autologous NK cells of tumor patients to directly lyse tumor cells is compromised while potent target cell lysis could be achieved upon induction of ADCC.46

Notably, besides in analyses with resting/briefly activated NK cells, also no relevant effect of GITR-Fc-KO was observed in degranulation assays with autologous patient NK cells. This could be due to exhaustion of patient NK cells and/or the immunosuppressive milieu caused by active leukemic disease, which may require longer times for therapeutic effects to manifest.4,24,31 Support for the latter hypothesis is provided by the fact that disruption of GITR–GITRL interaction by GITR-Fc-KO enhanced NK cell function in autologous lysis assays, which measure NK reactivity over 24 hours as compared with the 3 hours assay time in degranulation analyses. Importantly, GITR-Fc-ADCC, the therapeutic compound we aimed for in this study, profoundly stimulated NK reactivity in all experimental settings. It should also be noted that the effects of the fusion proteins varied substantially between different experiments, which supports the general notion that NK reactivity is governed by a balance of multiple activating and inhibitory signals that differ in individual patients and/or experimental settings.1 Varying GITRL and GITR expression levels on leukemic cells and (patient) NK cells, respectively, as well as F158V polymorphisms in CD16 that influence ADCC of allogenic and autologous NK cells but were not accounted for in our study may have contributed to the same.24,25,47 Despite these limitations, we are of the opinion that our analyses in the allogenic and autologous system together provide the best possible preclinical information on the therapeutic efficacy of our compounds, as results e.g., from mouse tumor models would be comprised by the different function(s) of GITR in mice and men.13,20,21

Induction of NK reactivity by the fusion proteins was strictly dependent on the expression of GITRL on the leukemic cells, thereby confirming that our constructs stimulate NK reactivity in a highly target antigen-restricted manner. With regard to a clinical application, it needs to be considered that expression of GITRL is not restricted to malignant cells, and expression was also detected e.g., on DC, monocytes/macrophages, B cells, and activated T cells.12,13 Thus, healthy GITRL-expressing immune effector cells could be affected upon application of GITR-Fc-ADCC. The expression levels of GITRL, but notably also of many other immunoregulatory molecules like NK inhibitory HLA class I, will determine whether the amount of activating signals is sufficient to induce relevant NK reactivity against these healthy cells or not. Even if no induction of ADCC against healthy hematopoietic cells was observed in our in vitro analyses, this does not exclude such side effects upon application of GITR-Fc-ADCC to patients in vivo. However, since GITRL is not expressed on healthy CD34+ cells,24 potential side effects, if occurring, likely would be of temporary nature, alike those occurring after application of Rituximab. Upon Rituximab treatment, healthy B cells are eliminated but reconstitute after about 9–12 months.48 While certainly further work on this and other open issues is required before patients with leukemia can ultimately be treated with GITR-Fc-ADCC, our data provide clear proof of concept that fusion proteins capable of blocking NK inhibitory molecules expressed by malignant cells while at the same time potently inducing ADCC may constitute an attractive means for immunotherapy of cancer.

Materials and Methods

Patients. PBMC of leukemia patients were isolated by density gradient centrifugation at the time of diagnosis before therapy after obtaining informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki protocol. The study was performed according to the guidelines of the local ethics committee.

Transfectants, antibodies, and reagents. The GITRL transfectants (C1R-GITRL) as well as control cells (C1R-neo) were previously described.42 The mAbs against GITR (clone 110416) and GITRL (clone 109101) as well as recombinant GITRL (sGITRL) were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The secondary Ig-PE-conjugates were from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA). All other antibodies were from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Recombinant IL-2 was from ImmunoTools (Friesoythe, Germany). Rituximab was obtained from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). All other reagents were from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Production and purification of GITR-Ig fusion proteins and Fc controls. SP2/0-Ag14 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were transfected with vectors coding for the different GITR-Ig fusion proteins by electroporation. Similar recombinant proteins lacking the GITR domain were generated as Fc controls. Subcloned transfectants were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 1 mg/ml G418. Fusion proteins were purified from culture supernatants by Protein A affinity chromatography (GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany). Purity was determined by non-reducing and reducing 10% SDS-PAGE and size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 PC3.2/30 column (SMART System; GE Healthcare). Endotoxin levels were <1 EU (endotoxin unit)/ml for all proteins.

Flow cytometry. FACS was performed using specific mAb, GITR-Ig fusion proteins, and controls at 10 µg/ml followed by specific PE-conjugates (1:100). Analysis was performed using a FC500 (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany).

Preparation of pNK cells. pNK cells were generated by incubation of non-plastic–adherent PBMC with irradiated RPMI 8866 feeder cells over 10 days in the presence of IL-2 (25 U/ml) as previously described.49 Functional experiments were performed when purity of pNK cells (CD56+CD3−) was above 90% as determined by flow cytometry.

NK cell activation, degranulation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production. Upregulation of CD69 and CD107a as markers for NK cell activation and degranulation, respectively, was analyzed by FACS using specific fluorescence conjugates. NK cells were generally selected by staining for CD56+CD3− and, in case of NK cells of AML patients, for CD56+CD3−CD33−CD34−. Direct cytotoxicity and ADCC of NK cells were analyzed by 2-hour BATDA europium assays as described previously.24 Percentage of lysis was calculated as follows: 100 × (experimental release: spontaneous release)/(maximum release: spontaneous release). IFN-γ production of NK cells was analyzed using the ELISA mAb set from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL) according to manufacturer's instructions. Lysis rates and cytokine concentrations in supernatants are shown as means of triplicate measurements.

FACS-based leukemia cell lysis assay. Leukemia cell lysis by autologous NK cells was determined using a FACS-based assay as previously described.45,50 In brief, AML and CLL cells among PBMC of leukemia patients were selected by staining for CD33+ and/or CD34+ and CD19+CD5+, respectively, and dying or dead cells were identified by 7-AAD positivity. Analysis of equal assay volumes was ascertained by adding unlabeled standard calibration beads to every sample, which also allowed for determining the number of leukemia cells that had vanished from the culture. Percentage of specific lysis was calculated as followed: 100: ((7-AAD negative cells in respective treatment/7-AAD negative cells in control) × 100). The results are shown as means of triplicate measurements.

Statistical analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test (one-tailed). Significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by asterisks (*).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Binding of GITR-Ig to healthy cells and consequences for NK reactivity. Figure S2. Comparative analysis of the effects of Rituximab and GITR-Fc-ADCC on NK cell reactivity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SA1360/7-1, SFB-685 TP A7, and C10), Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (2007.115.2), and Deutsche Krebshilfe (109620). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, Caligiuri MA, Zitvogel L, Lanier LL.et al. (2011Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells Science 33144–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:225–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Casucci M, Volpi I, Tosti A, Perruccio K.et al. (1999Role of natural killer cell alloreactivity in HLA-mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation Blood 94333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A.et al. (2002Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants Science 2952097–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins WL, Pickard A., and, Pierson GR. Deficient expression of class-I HLA in some cases of acute leukemia. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1984;18:91–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00205741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demanet C, Mulder A, Deneys V, Worsham MJ, Maes P, Claas FH.et al. (2004Down-regulation of HLA-A and HLA-Bw6, but not HLA-Bw4, allospecificities in leukemic cells: an escape mechanism from CTL and NK attack Blood 1033122–3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowdell MW, Craston R, Samuel D, Wood ME, O'Neill E, Saha V.et al. (2002Evidence that continued remission in patients treated for acute leukaemia is dependent upon autologous natural killer cells Br J Haematol 117821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson BA., and, Miller JS. CD56+bright and CD56+dim natural killer cells in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia progressively decrease in number, respond less to stimuli that recruit clonogenic natural killer cells, and exhibit decreased proliferation on a per cell basis. Blood. 1996;88:2279–2287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F, Kawatani T, Endo A., and, Kawasaki H. Natural killer cell activity and cytokine production as prognostic factors in adult acute leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:478–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretta L., and, Moretta A. Unravelling natural killer cell function: triggering and inhibitory human NK receptors. EMBO J. 2004;23:255–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM., and, Stephens GL. The GITR-GITRL interaction: co-stimulation or contrasuppression of regulatory activity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nri1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini G., and, Riccardi C. GITR: a modulator of immune response and inflammation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;647:156–173. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-89520-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placke T, Kopp HG., and, Salih HR. Glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related (GITR) protein and its ligand in antitumor immunity: functional role and therapeutic modulation. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:239083. doi: 10.1155/2010/239083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko K, Yamazaki S, Nakamura K, Nishioka T, Hirota K, Yamaguchi T.et al. (2005Treatment of advanced tumors with agonistic anti-GITR mAb and its effects on tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells J Exp Med 202885–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AD, Diab A, Perales MA, Wolchok JD, Rizzuto G, Merghoub T.et al. (2006Agonist anti-GITR antibody enhances vaccine-induced CD8(+) T-cell responses and tumor immunity Cancer Res 664904–4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Montagut T, Chow A, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Terwey TH, Kochman AA, Lu S.et al. (2006Glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family related gene activation overcomes tolerance/ignorance to melanoma differentiation antigens and enhances antitumor immunity J Immunol 1766434–6442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JS, Hsu JV., and, Morrison SL. Localized expression of GITR-L in the tumor microenvironment promotes CD8+ T cell dependent anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:1057–1069. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0622-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao J, Kamimura Y, Iwai H, Cao Y, Kikuchi K, Hashiguchi M.et al. (2009Enhancement of T-cell-mediated anti-tumour immunity via the ectopically expressed glucocorticoid-induced tumour necrosis factor receptor-related receptor ligand (GITRL) on tumours Immunology 127489–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai N, Ikeda H, Tawara I, Wang L, Wang L, Nishikawa H.et al. (2009Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor stimulation enhances the multifunctionality of adoptively transferred tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with tumor regression Cancer Sci 1001317–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levings MK, Sangregorio R, Sartirana C, Moschin AL, Battaglia M, Orban PC.et al. (2002Human CD25+CD4+ T suppressor cell clones produce transforming growth factor beta, but not interleukin 10, and are distinct from type 1 T regulatory cells J Exp Med 1961335–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuyaerts S, Van Meirvenne S, Bonehill A, Heirman C, Corthals J, Waldmann H.et al. (2007Expression of human GITRL on myeloid dendritic cells enhances their immunostimulatory function but does not abrogate the suppressive effect of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells J Leukoc Biol 8293–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz KM, Krusch M, Bringmann A, Brossart P, Mayer F, Kloss M.et al. (2007Cancer immunoediting by GITR (glucocorticoid-induced TNF-related protein) ligand in humans: NK cell/tumor cell interactions FASEB J 212442–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Li Z, Mahesh SP, Pantanelli S, Hwang FS, Siu WO.et al. (2008GITR negatively regulates activation of primary human NK cells by blocking proliferative signals and increasing NK cell apoptosis J Biol Chem 2838202–8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baessler T, Krusch M, Schmiedel BJ, Kloss M, Baltz KM, Wacker A.et al. (2009Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor-related protein ligand subverts immunosurveillance of acute myeloid leukemia in humans Cancer Res 691037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechele C, Baessler T, Wirths S, Schmohl JU, Schmiedel BJ., and, Salih HR. Glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein (GITR) ligand modulates cytokine release and NK cell reactivity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) Leukemia. 2012;26:991–1000. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner GJ. Rituximab: mechanism of action. Semin Hematol. 2010;47:115–123. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams GP., and, Weiner LM. Monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1147–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platsoucas CD, Fernandes G, Gupta SL, Kempin S, Clarkson B, Good RA.et al. (1980Defective spontaneous and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity mediated by E-rosette-positive and E-rosette-negative cells in untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: augmentation by in vitro treatment with interferon J Immunol 1251216–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler HW, Kay NE., and, Zarling JM. Deficiency of natural killer cell activity in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Cancer. 1981;27:321–327. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910270310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay NE., and, Zarling JM. Impaired natural killer activity in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with a deficiency of azurophilic cytoplasmic granules in putative NK cells. Blood. 1984;63:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglowski SM, Alinari L, Lapalombella R, Muthusamy N., and, Byrd JC. The clinical application of monoclonal antibodies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:3705–3714. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-001230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oflazoglu E., and, Audoly LP. Evolution of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapeutics in oncology. MAbs. 2010;2:14–19. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.1.10789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Wurch T, Bailly C., and, Corvaia N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of therapeutic antibodies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:345–352. doi: 10.1038/nri2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton HM, Bernett MJ, Pong E, Peipp M, Karki S, Chu SY.et al. (2008Potent in vitro and in vivo activity of an Fc-engineered anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody against lymphoma and leukemia Cancer Res 688049–8057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyil KV., and, Bartlett NL. Anti-CD30 Antibodies for Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2010;5:140–147. doi: 10.1007/s11899-010-0053-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton HM, Bernett MJ, Peipp M, Pong E, Karki S, Chu SY.et al. (2010Fc-engineered anti-CD40 antibody enhances multiple effector functions and exhibits potent in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against hematologic malignancies Blood 1163004–3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robak T. GA-101, a third-generation, humanized and glyco-engineered anti-CD20 mAb for the treatment of B-cell lymphoid malignancies. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:588–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar GA, Dang W, Karki S, Vafa O, Peng JS, Hyun L.et al. (2006Engineered antibody Fc variants with enhanced effector function Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1034005–4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour KL, Clark MR, Hadley AG., and, Williamson LM. Recombinant human IgG molecules lacking Fcgamma receptor I binding and monocyte triggering activities. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2613–2624. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2613::AID-IMMU2613>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles JA., and, Weiner GJ. CD16 polymorphisms and NK activation induced by monoclonal antibody-coated target cells. J Immunol Methods. 2005;304:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GP, Koebel CM., and, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:836–848. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz KM, Krusch M, Baessler T, Schmiedel BJ, Bringmann A, Brossart P.et al. (2008Neutralization of tumor-derived soluble glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein ligand increases NK cell anti-tumor reactivity Blood 1123735–3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Lin BR, Lin B, Hou S, Qian WZ, Li J.et al. (2009Pharmacokinetics of CTLA4Ig fusion protein in healthy volunteers and patients with rheumatoid arthritis Acta Pharmacol Sin 30364–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locksley RM, Killeen N., and, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechele C, Baessler T, Schmiedel BJ, Schumacher CE, Grosse-Hovest L, Rittig K.et al. (20124-1BB ligand modulates direct and Rituximab-induced NK-cell reactivity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia Eur J Immunol 42737–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst MR, Riley JP, Dudley ME., and, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive transfer of autologous natural killer cells leads to high levels of circulating natural killer cells but does not mediate tumor regression. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6287–6297. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koene HR, Kleijer M, Algra J, Roos D, von dem Borne AE., and, de Haas M. Fc gammaRIIIa-158V/F polymorphism influences the binding of IgG by natural killer cell Fc gammaRIIIa, independently of the Fc gammaRIIIa-48L/R/H phenotype. Blood. 1997;90:1109–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin P, Grillo-López AJ, Link BK, Levy R, Czuczman MS, Williams ME.et al. (1998Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program J Clin Oncol 162825–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedel BJ, Arélin V, Gruenebach F, Krusch M, Schmidt SM., and, Salih HR. Azacytidine impairs NK cell reactivity while decitabine augments NK cell responsiveness toward stimulation. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2911–2922. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann M, Große-Hovest L, Nübling T, Pyz E, Bamberg ML, Aulwurm S.et al. (2012Generation, selection and preclinical characterization of an Fc-optimized FLT3 antibody for the treatment of myeloid leukemia Leukemia 261228–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.