Abstract

While there have been attempts to explore the association of obesity and risky sexual behaviors among gay men, findings have been conflicting. Using a prospective cohort of gay and bisexual men residing in Pittsburgh, we performed a semi-parametric, group-based analysis to identify distinct groups of trajectories in body mass index slopes over time from 1999 to 2007 and then correlated these trajectories with a number of psychosocial and behavioral factors, including sexual behaviors. We found many men were either overweight (41.2%) or obese (10.9%) in 1999 and remained stable at these levels over time, in contrast to recent increasing trends in the general population. Correlates of obesity in our study replicated findings from the general population. However, we found no significant association between obesity and sexual risk-taking behaviors, as suggested from several cross-sectional studies of gay men. While there was not a significant association between obesity and sexual risk-taking behaviors, we found high prevalence of overweight and obesity in this population. Gay and bisexual men’s health researchers and practitioners need to look beyond HIV and STI prevention and also address a broader range of health concerns important to this population.

Keywords: Sexual behavior, Obesity, Quality of life, HIV risks, Gay and bisexual men’s health, Men who have sex with men

Introduction

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) reported that the United States is in the midst of an obesity epidemic, spanning across age, gender, racial and ethnic groups, and geographic regions (Flegal, Carroll, Ogden, & Johnson, 2002; Ogden et al., 2006). Among men, the trend towards obesity significantly increased between 1999 and 2006. The rapid increase in the prevalence of obesity in the general U.S. population suggests that psychosocial and behavioral factors may have key roles in the development and/or sustaining of these rates (Stice, Presnell, Shaw, & Rohde, 2005; Vaidya, 2006). Factors such as race/ethnicity, income, education, social support, and depression have also been linked to obesity. However, there is little information to elucidate whether similar phenomena also exist among gay and bisexual men.

The few studies that have been conducted among overweight and obese gay men tend to focus on sexual behaviors or body image alone, and these studies are often limited to cross-sectional designs with conflicting findings (Allensworth-Davies, Welles, Hellerstedt,& Ross, 2008; Kraft, Robinson, Nordstrom, Bockting, & Rosser, 2006; Moskowitz & Seal, 2010). Kraft et al. found that obesity was associated with safer sex, after adjusting for body image and age. Non-obese men, in particular, were more likely to engage in sexual activities in the past 3 months. Similarly, Allensworth-Davies et al. found that overweight and obese men engaged in less unprotected anal intercourse. However, Moskowitz and Seal found that increased body mass index (BMI) was associated with decreased condom use. Therefore, it is unclear whether there is a relationship between higher BMI and sexual risk-taking behaviors. Moreover, there is little information whether higher BMI is associated with other psychosocial factors among gay and bisexual men. In this article, we examined the trends of BMI overtime, and then evaluated whether these trends were associated with psychosocial and behavioral factors among a prospective cohort of healthy weight, overweight, and obese gay and bisexual men.

Method

Participants

We analyzed longitudinal data (n =379) from 1999 to 2007 in the Pitt Men’s Study (PMS), an on-going cohort that examines the epidemiology of HIV infection and progression among gay and bisexual men (defined as having had oral or anal sex with another male in the past 7 years) residing in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. PMS is one of four sites of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). Enrollment of participants into the cohort occurred three times: 1984–1985, 1987–1991, and 2001–2003. The inclusion criteria, recruitment, and sampling strategies are described in greater detail elsewhere (Silvestre et al., 1986, 2006). Briefly, participants were recruited using community organizing principles and social marketing campaigns that actively engaged the gay and bisexual community itself and that focused on building trust, particularly with racial and ethnic minority gay and bisexual men. A community advisory board was created and involved community members in all aspects of study design, planning, and dissemination of findings. Since 1984, participants in the study have been followed every 6 months with a detailed questionnaire-based interview, physical examination, and medical history review. The retention rate for the time period being analyzed for this article was 75%.

To mirror the time period investigated in NHANES, we used data from October 1999 to March 2007. Individuals were excluded from our analysis if they: (1) had missing data on height and weight across all visits, (2) contributed only one data point or (3)were HIV positive at any point during the time period that was analyzed. HIV-positive individuals were excluded from our analysis because we did not want the effect of HIV medications, disease progression or higher prevalence of recreational drug use, including methamphetamine use, to confound our findings(Brown et al., 2007; Plankey et al., 2007). A total of 379 participants met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis.

Measures

BMI scores were calculated (weight in pounds ×703)/(height in inches2) and grouped into CDC categories of underweight (<18.5), healthy weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9), and obese (>29.9). (We used the term “healthy weight” in place of “ normal weight” because it may seem offensive to imply that other categories are abnormal.) To test the internal validity of BMI (e.g., men with above average muscle mass and below average fat levels having higher BMI), we ran a similar analysis using waist circumference and found no differences in the trajectories over time.

Sexual activities and sexual partners were assessed by asking if participants had “any sort of sexual activity with a man,” followed by a question about the number of oral and anal sex partners as well as sexual activities with partners that did not involve sexual intercourse in the past 6 months.

Quality of life-related constructs were assessed using the modified Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992), which have previously been evaluated for reliability and validity in the MACS (Bing et al., 2000). The raw scores for the items of each subscale were summed and transformed linearly to a range of 0–100, with higher values for better functioning and well being.

Participants were asked if they were currently using the following substances in the previous 6 months: poppers or nitrite inhalants, crack cocaine, other forms of cocaine, and methamphetamines (“crystals,” “speed,” “ice”). We grouped crack cocaine, other forms of cocaine and methamphetamine, into “stimulants” for this article. Frequent use of substances was defined as weekly use or more. Participants were considered currently smoking if they reported ‘yes’ to the question: “smoke cigarettes now? (as of 1 month ago).” Binge drinking was defined as five or more drinks per occasion occurring at least monthly.

Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 20-item CES-D, which was directly adapted from the instrument developed by Raldoff (1977). The frequency of each psychological symptom in the previous week was assigned a value: 0 = “rarely or none of the time (<1 day per week),”1 = “some or little of the time (1–2 day per week),”2 = “occasionally or moderate amount of the time (3–4 days per week),” or 3 = “most or all of the time (5–7 days per week).”A threshold of 16 or more has been shown to be indicative of significant depressive symptoms and predictive of HIV morbidity and mortality among participants in the MACS (Farinpour et al., 2003). A threshold of 22 has been used to approximate “major depression” in a previous study of depression among urban gay and bisexual men (Mills et al., 2004).

Statistical Analyses

After testing for variability of the intercepts and slopes of individual BMI trajectories across time using a random effects model (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), a semi-parametric, group-based approach (Nagin, 1999) was used to model the individual trajectories of BMI across time. The random effects and group-based models were analyzed using proc mixed and proc traj, respectively (Nagin, 2005), in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC). Group-based model evaluation and selection criteria were based on recommendations by Nagin (2005). A censored normal model was used to accommodate the possibility of clustering within the scale of 0–30. The optimal number of trajectory groups was selected based on Nagin’s criteria: (1) substantive theory, (2) Bayesian information criteria, (3) average posterior probabilities (AvePP), and (4) group size. After the optimum number of trajectories was selected, the trend of each trajectory (linear, quadratic, cubic function of age) was determined. Chi-square and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to test group differences in participants’ characteristics at the most recent visit (Table 1). Multivariate logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationships between obesity and risky sexual behaviors, adjusting for age and race at baseline (Table 2). These variables have been found to be correlates of obesity in previous studies (Flegal et al., 2002; Ogden et al., 2006). The data analysis performed for this paper was determined a non-human subjects research activity by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Demographic and behavioral characteristics of different weight status groups among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in the PMS, 1999–2007 (N =379)

| Group characteristicsa | BMI

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy weight (n =182) | Overweight (n =155) | Obese (n =42) | χ2/ANOVA f-test statistics | p | |

| Non-white % | 15.9 | 21.3 | 33.3 | 6.69 | .035 |

| Less than high school | 6.0 | 2.6 | 7.1 | 2.82 | ns |

| Unemployment, seeking % | 28.0 | 23.0 | 31.0 | 3.74 | ns |

| Unemployment, not seeking % | 7.7 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 0.48 | ns |

| Financial difficultyb % | 41.2 | 39.4 | 57.1 | 4.43 | ns |

| Smoking % | 46.2 | 40.7 | 35.7 | 1.99 | ns |

| Binge drinking % | 23.1 | 21.3 | 14.3 | 1.57 | ns |

| Frequent poppers usec % | 9.9 | 10.3 | 2.4 | 2.67 | ns |

| Frequent stimulant usec,d % | 9.3 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 2.61 | ns |

| CESD ≥ 16% | 56.6 | 47.1 | 50.0 | 3.10 | ns |

| CESD ≥ 22% | 37.9 | 37.4 | 38.1 | 0.01 | ns |

| Treatment for depression % | 37.9 | 45.2 | 38.1 | 1.97 | ns |

| Used mental health services % | 34.1 | 41.9 | 33.3 | 2.52 | ns |

| Mean age at last visit (SD) | 46.7 (13.3) | 52.4 (11.6) | 49.8 (11.2) | 8.65 | <.001 |

| General health perceptione (SD) | 77.0 (15.9) | 73.4 (17.6) | 67.7 (17.8) | 5.66 | .004 |

| Physical functioninge (SD) | 93.2 (11.6) | 88.1 (17.2) | 80.2 (24.3) | 12.9 | <.001 |

| Role limitations due to physical healthe (SD) | 89.0 (18.3) | 84.6 (23.8) | 80.9 (26.2) | 3.24 | .04 |

| Emotional well-beinge (SD) | 74.5 (17.1) | 75.2 (17.3) | 73.3 (17.2) | 0.24 | ns |

| Role limitations due to emotional problemse (SD) | 80.6 (24.9) | 78.3 (30.6) | 82.1 (25.9) | 0.45 | ns |

| Social functioninge (SD) | 85.8 (15.2) | 84.5 (18.6) | 82.6 (20.6) | 0.67 | ns |

| Mean number of male intercourse partners (SD) | 5.9 (9.3) | 5.0 (8.1) | 4.6 (6.7) | 0.58 | ns |

| Any sexual activity % | 24.7 | 32.9 | 35.7 | 3.64 | ns |

| NUAII ≥ 2 partners % | 24.2 | 23.2 | 21.4 | 0.15 | ns |

| NUARI ≥ 2 partners % | 16.5 | 13.6 | 9.5 | 1.53 | ns |

BMI body mass index, NUAII number of unprotected anal insertive intercourse partners, NUARI number of unprotected anal receptive intercourse partners

The variables in this table were taken across all visits between October 1999 and March 2007

Any major financial difficulty meeting basic expenses

Weekly use or more

Stimulant includes crack, cocaine, and methamphetamines

Mean SF-36 linear scores

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic model of risky sexual behaviors and obesity among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in the PMS, 1999–2007 (N =379)

| Correlates of obesity (BMI>29.9) | Adjusted odds ratios (OR)a | 95% confidence intervals (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Consistent condom use | 0.75 | (0.14, 4.20) |

| High number of sexual partners (3 or more) | 1.27 | (0.52, 3.12) |

OR adjusted for age and race at baseline

Results

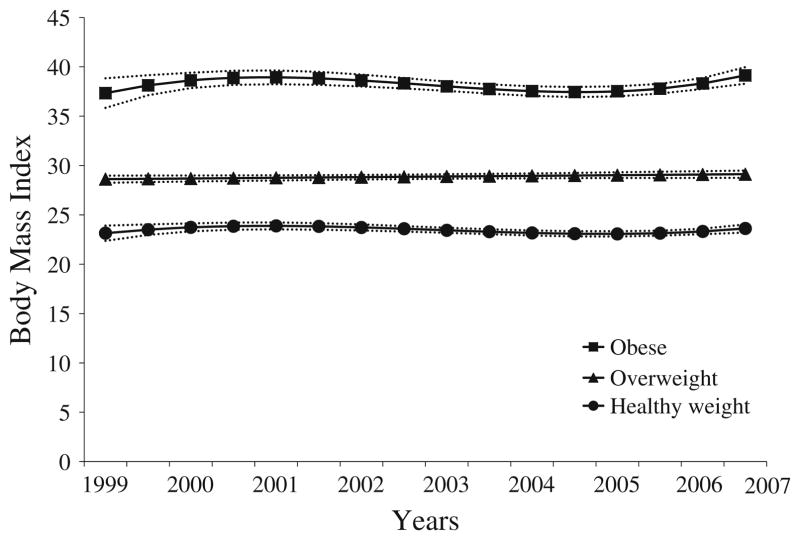

The analysis produced three distinct trajectories from 1999 to 2007 (Fig. 1): “healthy weight group”(n =182, median BMI of 23.5), “overweight group”(n =155, median BMI of 28.6), and “obese group”(n =42, median BMI of 36.9). The probabilities of being in the healthy weight, overweight, and obese groups across the visits were 47.9% (average posterior probability of group membership(AvePP) =0.969),43.5%(AvePP =0.966), and 9.4% (AvePP =0.980), respectively. The trajectories were also generally stable across the eight-year period with no significant linear increasing or decreasing trends among the healthy weight and obese groups (p =.09 and p =.88, respectively). However, the overweight group seems to be increasing over the time period, though only at borderline significance (p =.06).

Fig. 1.

Trajectories of BMI among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in the PMS, 1999–2007. BMI over time October 1999–March 2007: Group 1, healthy weight group (47.9%, n =182); Group 2, overweight group (41.2%, n =155); Group 3, obese group (10.9%, n =42). Dash lines represent the 95% confidence intervals on trajectories

Table 1 shows significant demographic correlates of over-weight or obesity that included being non-White and being older (p =.04 and p<.001, respectively). Mean SF-36 scores were significantly different across groups, with obese men reporting worse quality of life outcomes. There were no significant differences in substance abuse, depression based on CES-D scores or risky sexual behaviors across the three groups. About 40% of the obese men reported no sexual partners in the past month. Adjusting for age and race, consistent condom use or having a higher number of sexual partners were not correlates of obesity (Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal analysis of weight status of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in the United States. Consistent with national data of the general population, we found that these men had a high prevalence of being either overweight or obese. Specifically, over 50% were either overweight or obese. However, contrary to the increasing trends in the national data over this same time period(Ogden et al., 2006), these men sustained their weight levels. With respect to correlates, we found no significant differences in HIV risk behaviors, depression or substance use variables by weight status.

This study has some limitations that should be noted. First, while the PMS has a relatively diverse group of men (i.e., the proportion of non-white gay and bisexual men in the sample exceeds that of the population of southwestern Pennsylvania), the generalizablility of these findings to all southwestern Pennsylvania gay and bisexual men is limited. Second, low numbers in the obese category may limit the power to detect actual differences between groups. However, we do not feel that the recruitment methods in the PMS undersampled obese men since recruitment did not merely focus on entertainment venues (e.g., gay bars). Still, probability sampling would have been the best method to recruit participants. Hence, including sexual identity, sexual orientation, and same-sex sexual behavioral markers in national longitudinal studies is needed.

As gay men age, chronic illnesses, like heart disease, diabetes, and stroke, may become equally as important as HIV/AIDS for morbidity and mortality burdens. The gay community, along with numerous community-based organizations, do not seem to emphasize obesity prevention (Gay Men’s Health Crisis, 2011). In our analysis, we found that a significant number of gay and bisexual men were, in fact, overweight or obese, suggesting a need for obesity-related public health interventions to include gay and bisexual men. Additionally, our findings did not replicate earlier cross-sectional findings that obese gay men engage in more risky sexual activities (Moskowitz & Seal, 2010). To move the field forward, research on obesity among gay and bisexual men should extend beyond HIV concerns and expand to chronic conditions and their risk (e.g., binge eating, sedentary life style) and protective factors that are likely to become increasingly important predictors of health as men age. The Surgeon General, the American Public Health Association, and the American Medical Association have all called for more research and greater attention to the health needs of LGBT people based on several convenience studies related to drug and alcohol use, mental health issues, violence, smoking, and other health issues. This study suggests that excess weight is also an area needing attention, at least as it affects some segment of the gay and bisexual male community. Our data suggest that major longitudinal studies should be carried out to provide data not available in cross-sectional studies. It also suggests that research on weight loss interventions need to be carried out to ascertain whether they are effective for LGBT people or whether interventions need to be adapted or new ones developed. Since many interventions involve participation in groups of peers and/or require disclosing information about one’s family life or lifestyles, these interventions may not be useful for LGBT people who feel a need to maintain privacy about their sexual orientation. As with smoking, factors related to weight gain might be different for LGBT people and need to be understood if interventions are to work. Finally, new interventions may be useful, for example, an intervention could be developed with input and support from and focused on gay male social groups that have already been organized for overweight men (e.g., Bears).

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants and staff of the Pitt Men’s Study, in particular, Carol Perfetti. The U.S. National Institutes of Health funded the following individuals: Thomas E. Guadamuz (DA022936), Sin How Lim (DA025952), Michael P. Marshal (AA015100), and Mark S. Friedman (MH080648). The MACS was supported by the following grants: UO1-AI-35039, UO1-AI-35040, UO1-AI-35041, UO1-AI-35042, and UO1-AI-35043.

Contributor Information

Thomas E. Guadamuz, Email: tguadamu@hotmail.com, Center for Research on Health and Sexual Orientation, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, 231 Parran Hall, 130 DeSoto St., Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA

Sin How Lim, Center for Research on Health and Sexual Orientation, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Epidemiology, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Michael P. Marshal, Center for Research on Health and Sexual Orientation, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Mark S. Friedman, Center for Research on Health and Sexual Orientation, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, 231 Parran Hall, 130 DeSoto St., Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA

Ronald D. Stall, Center for Research on Health and Sexual Orientation, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, 231 Parran Hall, 130 DeSoto St., Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA

Anthony J. Silvestre, Center for Research on Health and Sexual Orientation, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

References

- Allensworth-Davies D, Welles SL, Hellerstedt WL, Ross MW. Body image, body satisfaction, and unsafe anal intercourse among men who have sex with men. Journal of Sex Research. 2008;45:49–56. doi: 10.1080/00224490701808142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Hays RD, Jacobson LP, Chen B, Gange SJ, Kass NE, et al. Health-related quality of life among people with HIV disease: Results from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Quality of Life Research. 2000;9:55–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1008919227665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TT, Chu H, Wang Z, Palella FJ, Kingsley L, Witt MD, et al. Longitudinal increases in waist circumference are associated with HIV-serostatus, independent of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21:1731–1738. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328270356a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinpour R, Miller EN, Satz P, Selnes OA, Cohen BA, Becker JT, et al. Psychosocial risk factors of HIV morbidity and mortality: Findings from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study(MACS) Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2003;25:654–670. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.654.14577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Accessed 12 Oct 2011.];Gay Men’s Health Crisis. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.gmhc.org/

- Kraft C, Robinson BB, Nordstrom DL, Bockting WO, Rosser BR. Obesity, body image, and unsafe sex in men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:587–595. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, Pollack L, Canchola J, Chang YJ, et al. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:278–285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DA, Seal DW. Revisiting obesity and condom use in men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:761–765. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9478-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semi-parametric group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plankey MW, Ostrow DG, Stall R, Cox C, Li X, Peck JA, et al. The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk of HIV seroconversion in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;45:85–92. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180417c99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raldoff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre AJ, Hylton JB, Johnson LM, Houston C, Witt M, Jacobson L, et al. Recruiting minority men who have sex with men for HIV research: Results from a 4-city campaign. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1020–1027. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre AJ, Lyter DW, Rinaldo CR, Kingsley LA, Forrester R, Huggins J. Marketing strategies for recruiting gay men into AIDS research and education projects. Journal of Community Health. 1986;11:222–232. doi: 10.1007/BF01325118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Presnell K, Shaw H, Rohde P. Psychological and behavioral risk factors for obesity onset in adolescent girls: A prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:195–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya V. Psychosocial aspects of obesity. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;27:73–85. doi: 10.1159/000090965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]