Abstract

MarR family proteins constitute a group of >12 000 transcriptional regulators encoded in bacterial and archaeal genomes that control gene expression in metabolism, stress responses, virulence and multi-drug resistance. There is much interest in defining the molecular mechanism by which ligand binding attenuates the DNA-binding activities of these proteins. Here, we describe how PcaV, a MarR family regulator in Streptomyces coelicolor, controls transcription of genes encoding β-ketoadipate pathway enzymes through its interaction with the pathway substrate, protocatechuate. This transcriptional repressor is the only MarR protein known to regulate this essential pathway for aromatic catabolism. In in vitro assays, protocatechuate and other phenolic compounds disrupt the PcaV–DNA complex. We show that PcaV binds protocatechuate in a 1:1 stoichiometry with the highest affinity of any MarR family member. Moreover, we report structures of PcaV in its apo form and in complex with protocatechuate. We identify an arginine residue that is critical for ligand coordination and demonstrate that it is also required for binding DNA. We propose that interaction of ligand with this arginine residue dictates conformational changes that modulate DNA binding. Our results provide new insights into the molecular mechanism by which ligands attenuate DNA binding in this large family of transcription factors.

INTRODUCTION

Microorganisms exhibit unparalleled capabilities for the consumption of naturally occurring and man-made sources of carbon. Their impressive ability to consume inert aromatic compounds is critical for environmental carbon cycling and has major implications for bioremediation, alternative energy and sustainable production of chemical feedstocks (1). Much of the microbial catabolism of aromatic compounds is related to lignin, a highly abundant polymer that is one of the components of plant biomass (2,3). A central pathway for the consumption of the lignin-derived aromatic compounds is the β-ketoadipate pathway. In this pathway, protocatechuate (3,4-dihydroxybenzoate; referred to hereafter as PCA) and catechol are converted into the eponymous β-ketoadipate and, ultimately, acetyl-coenzyme and succinyl-coenzyme A (4). The fact that these products can be converted anabolically into triglyceride precursors of biodiesel or into high-value compounds like polyketide antibiotics has motivated much renewed interest in this pathway (5).

In addition to being a prototype for the catabolism of lignin-derived aromatic compounds, the β-ketoadipate pathway has been a model system for studies of how microorganisms regulate the catabolism of aromatic compounds at the genetic level (4,6–15). The theme that has emerged from the investigations by multiple groups is that genes encoding enzymes of the pathway are regulated by either LysR or IclR family transcription factors (4,16). Mostly, these transcription factors mediate environmental surveillance as receptors for aromatic ligands that modulate their DNA-binding ability. Our recent studies of aromatic catabolism in Streptomyces bacteria resulted in the discovery of a MarR family transcription factor called PcaV that regulates genes encoding enzymes of the PCA branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway (14). Beyond its regulation of a central pathway for aromatic catabolism, PcaV is of interest because it is the only known member of the MarR family that regulates the β-ketoadipate pathway.

The MarR family of transcription factors is a large group of proteins encoded by >12 000 genes in the publicly available genomes of bacteria and archaea. While these proteins can be either transcriptional repressors or activators, they have been ascribed roles in controlling the expression of genes underlying catabolic pathways, stress responses, virulence and multi-drug resistance (17–21). To date, the physiological roles of ∼100 of these proteins have been characterized in detail (22). While a subset of MarR family members regulate adaptive responses to oxidative stress through the formation of disulfide bonds that influence DNA binding (23–27), the majority of these proteins regulate gene expression through ligand-mediated attenuation of DNA binding. Our understanding of the molecular mechanism of regulation by ligand-responsive MarR family proteins is limited because the identity of the ligand is often unknown (22,28). Further, in most cases wherein structures of MarR family members in complex with ligands have been reported, the ligand’s physiological role cannot be easily connected to the functions of the regulated genes (22,29). As MarR family members play important roles in antibiotic resistance, virulence and catabolism, studies of their molecular mechanisms have implications for medicine and biotechnology.

Our discovery that PCA regulates the PcaV-dependent transcriptional activation of the corresponding structural genes in Streptomyces coelicolor provided a unique opportunity to study how a MarR family transcription factor responds to its natural ligand. Bioinformatics, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), mutagenesis, isothermal calorimetry (ITC) and in vivo transcription assays were used to elucidate the regulatory mechanism of PcaV. Further, we report the crystal structures of apo-PcaV and PcaV bound to its ligand PCA. Our findings are particularly noteworthy because they provide a contrast to the few crystal structures of MarR family members bound to ligands whose identities cannot be connected to the functions of the genes that they regulate and, as a consequence, new insights into the molecular basis of the transcriptional regulation of MarR proteins by their native ligands.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria–Bertani medium at 37°C, unless noted otherwise. Streptomyces strains were grown on mannitol soya flour medium, on Difco nutrient agar medium and in minimal liquid medium (NMMP) (30) at 30°C. Streptomyces were grown in NMMP for RNA isolations. For selection of E. coli, ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and hygromycin (75 μg/ml) were used. In conjugations with S. coelicolor, nalidixic acid (20 μg/ml) was used to counterselect E. coli.

Mapping of transcriptional start site of pcaI

Wild-type (WT) S. coelicolor M600 was grown in NMMP for 14 h (mid-exponential phase), after which PCA was added at final concentration of 2 mM. After 1 h of induction, 1 ml of cells was pelleted and washed once with 10.3% (w/v) sucrose solution followed by the addition of 100 μl of 10 mg/ml lysozyme solution (50 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). The cells were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol and quantified using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Using Invitrogen’s 5′ RACE System for Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends kit, the first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using 20 pmol of primer pcaI GSP1 and 2000 ng of RNA template according to the manufacturer’s protocol for high GC-content transcripts. After cDNA synthesis, the reaction mixture was treated with an RNase Mix to remove template RNA and purified using the S.N.A.P. column procedure. An oligo-dC tail was added to the purified cDNA using the TdT-tailing reaction. Amplification of dC-tailed cDNA was accomplished using a 5 μl aliquot of the preceding reaction as template, the primers pcaI GSP2 and abridged Anchor primer (provided by manufacturer) and Taq DNA polymerase. The resulting polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product was used in a second PCR reaction using the primers pcaI GSP3 and abridged universal amplification primer (provided by the manufacturer). The first and second PCR products were ligated into the pGEM-T easy vector and transformed into the E. coli strain DH5α to yield pJS361 and pJS362. DNA sequencing of cloned inserts was performed by Davis Sequencing (Davis, CA).

Bioinformatic analysis of intergenic regions

Regulatory motifs were predicted using the Gibbs Motif Sampler (31). The Gibbs recursive sampler with prokaryotic default settings was used. Intergenic sequences between the pcaV gene and pcaI/pcaH genes in various Streptomyces species were compiled using Integrated Microbial Genomes provided by the Joint Genome Institute (32). ClustalW2 was used for sequence alignments, and WebLogo (33) was used to generate sequence logos.

Expression and purification

The pcaV gene (SCO6704) was PCR-amplified from S. coelicolor cosmid St4C6 and ligated into pBluescript KS+ to yield pJS363. The fragment containing the pcaV gene was excised and ligated into the vector pET28a-c(+) (Novagen) using the restriction sites NdeI and HindIII to yield pJS364. pJS364 was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) Gold cells (Stratagene). Large-scale cultures were grown to an OD600 between 0.6 and 0.8, and then pcaV expression was induced upon the addition of IPTG at a final concentration of 0.5 mM and allowed to proceed for at 18°C for 18 h. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 5 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl and 0.1% Triton X-100), subjected to high-pressure homogenization (Avestin) and centrifuged to remove cell debris. The cell lysate was loaded onto a HisTrap HP Ni2+-affinity column (GE Healthcare) and eluted using an imidazole gradient of 5–500 mM. Fractions containing PcaV were collected and dialyzed overnight against 50 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 at 4°C in the presence of thrombin for the cleavage of the N-terminal His6 tag. A second Ni2+-affinity purification was used to remove the His6 tag. Finally, dimeric PcaV was isolated using a Superdex 75 26/60 (GE Healthcare) size-exclusion chromatography column. The final purified protein was concentrated using centrifugation and stored in 10 mM Tris, 250 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, at −80°C.

Site-directed mutagenesis of PcaV

Single amino acid substitutions in PcaV were accomplished using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Primers PcaV R15A For and PcaV R15A Rev were used to generate pJS365 from pJS363. The mutagenized gene was subcloned into pET28a-c(+) to generate pJS366. Primers PcaV R15K For and PcaV R15K Rev were used to generate pJS367 from pJS364. The resulting constructs were confirmed through sequencing (Davis Sequencing) before expression. The PcaV R15A and PcaV R15K mutants were expressed and purified using the same procedure as WT PcaV, with the exception that PcaV R15A was stored in 10 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.5.

Agarose EMSAs

The DNA probes were amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase and the primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. Cosmid DNA was used to amplify probes for S. coelicolor and Streptomyces scabies, whereas genomic DNA was used for amplification of the Streptomyces avermitilis probe. The PCR program used for amplification was 94°C for 2 min, 20 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, followed by an elongation time of 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were purified using Qiagen’s PCR Purification Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA concentration was determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Binding of PcaV to DNA fragments was performed in 20 μl reactions containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 μg poly(dI-dC), 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Each reaction contained 20 nM DNA and between 65 and 780 nM PcaV. The effect of aromatic compounds on the binding of PcaV to DNA was determined by adding the compounds to the pre-formed PcaV–DNA reaction mixture. All compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 15 min, loaded onto a 2% agarose gel and run in tris-borate EDTA (TBE) buffer at 50 V for 2 h. Gels were subsequently stained in ethidium bromide for visualization of DNA. EMSA reactions with PcaV R15A and PcaV R15K were performed using the same procedure as described for WT PcaV.

Quantitative EMSAs

To generate 100-bp DNA probes, 5′ biotin-labeled primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies and used in PCR reactions with Pfu polymerase to generate biotin-labeled EMSA probes. The PCR program used for amplification was 94°C for 2 min, 20 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, followed by an elongation time of 10 min at 72°C. Labeled PCR products were purified using Qiagen’s PCR Purification Kit. DNA concentrations were determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. For 30-bp DNA probes, complementary 3′ biotin-labeled oligonucleotides containing operator sites were mixed in equimolar amounts in 10 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5, and annealed by heating to 95°C for 5 min and decreasing 1°C min−1. The Lightshift Chemilumenscent EMSA kit (Pierce) was used to prepare binding reactions. Each reaction contained either 50 fmol (PCR-amplified probes) or 100 fmol (30-bp annealed probes) of labeled DNA and varying concentrations of PcaV (purified immediately before use). Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 20 min and loaded onto a 6% DNA retardation gel (Invitrogen). Electrophoresis was accomplished at 100 V in TBE buffer for 85 min at 4°C. DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane at 395 mA for 40 min and UV cross-linked at 302 nm for 15 min. Membranes were subsequently developed using the Lightshift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Signals were detected using a Typhoon 9410 imager. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Band volumes were quantified using ImageQuant TL software, and Sigmaplot 8.0 was used to calculate dissociation constants.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

The binding of aromatic ligands to PcaV was observed using a MicroCal VP-ITC titration calorimeter. Ligand solutions were prepared in protein buffer, and the pH was adjusted to a final value of 7.5. The final concentrations of ligands were as follows: PCA (140 μM), 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate (300 μM), 3-hydroxybenzoate (350 μM), 4-hydroxybenzoate (1.5 mM) and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoate (1.5 mM). The 4-hydroxybenzoate and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoate molecules are low-affinity ligands, and thus these experiments were performed using the criteria established by Turnbull and Daranas for the analysis of low-affinity systems using ITC (34), namely, that there was a high molar ratio of ligand versus protein at the end of the titration, that the concentrations were accurately known, that there was adequate signal-to-noise and that the stoichiometry (1:1) was known. Both the ligand and protein solution were thoroughly degassed to remove air bubbles. A 15 μM solution of PcaV was loaded into the sample cell, while the injection syringe was loaded with the ligand solution. Titration reactions were performed with 28 injections, all 10 μl in volume, with constant stirring at 394 rpm at 25°C. The experiments with PcaV R15A and PcaV R15K were performed using the same procedure, with the exception that 1.5 mM PCA was used. Each experiment was done in duplicate or triplicate. Data were analyzed using Origin version 7 software (Microcal) to calculate dissociation constants.

PcaV crystallization

WT PcaV

Purified PcaV (10 mg/ml) was subjected to coarse grid crystallization screens using sitting-drop vapor diffusion. Crystals grew at 4°C in 0.2 M ammonium chloride and 20% w/v polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 in a drop containing 4 μl protein and 2 μl crystallization condition. Crystals were cryoprotected by a short soak in mother liquor supplemented with 25% glycerol and then frozen by direct transfer to liquid nitrogen.

PcaV–PCA complex

A solution containing PcaV (10 mg/ml) and a 10-fold molar excess of PCA (solubilized in protein buffer) was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, followed by brief centrifugation to remove any precipitation and immediately used in crystallization trials. Crystals grew in 0.2 M lithium acetate and 20% w/v PEG 3350 using sitting-drop vapor diffusion at 4°C in a drop containing 0.2 μl protein and 0.4 μl crystallization condition. The crystal was cryoprotected by transfer to mother liquor supplemented with 20% glycerol and then frozen directly in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection and structure refinement

PcaV–PCA

Data were collected at NSLS beamline X25 at 100 K and 0.9795 Å with the ADSC Q315 CCD detector. Data were indexed and scaled using HKL2000 (35) in space group P212121. The Fold and Function Assignment Server (FFAS) (36) identified a putative transcriptional regulator from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (−54.4 score, 29% sequence identity, PDB ID 2NNN) as a homologous structure that served as a molecular replacement (MR) search model. The initial MR search model was generated using a poly-Ala model (all side chains truncated at Cβ) of a single monomer. Molecular replacement was performed with AutoMR in Phenix (37) by searching for two copies of the search model, followed by Phenix AutoBuild using the model and map coefficients from AutoMR along with the PcaV sequence. MR yielded a single solution in P212121, and after AutoBuild, the model included 253 of 314 residues with an R/Rfree of 0.26/0.3. After an initial round of refinement, there was clear positive density (>5σ) corresponding to the PCA ligand. The PCA structure was downloaded from PDB ligand expo (PDB code DHB) and the refinement restraint parameters generated using Phenix Elbow. The PcaV–PCA model was improved through successive rounds of model building in Coot (38), followed by refinement with Phenix. A final refinement was performed using TLS groups determined by the TLSMD server (39). The final model contains 283 residues (residues 1–141 for each PcaV monomer plus one residue from the N-terminal expression tag) and two PCA molecules.

WT PcaV

Data were collected at NSLS beamline X25 at 100K and 1.1 Å using the Pilatus 6 M CCD detector. Diffraction data were indexed and scaled using HKL2000 (35) in space group I4122. Based on unit cell parameters, the calculated Matthew’s coefficient was 3.78 A3/Da, which corresponds to one molecule per asymmetric unit. The initial model was obtained by molecular replacement using the PcaV–PCA structure as a search model. The final WT PcaV model was produced through iterative rounds of model building in Coot (38) and structure refinement in Phenix (37) and contains one PcaV molecule (residues 8–143). The second molecule of the PcaV dimer is related to the first molecule through a perfect crystallographic two-fold symmetry axis. All figures were generated using Pymol (Schrödinger, LLC). A summary of the crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics is presented in Table 1. The structure factors and coordinates for WT PcaV and PcaV–PCA complex have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 4G9Y and 4FHT, respectively.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| WT PcaV | PcaV–protocatechuate | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | I4122 | P212121 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a = b = 102.77, c = 100.31 | a = 62.36, b = 63.97, c = 73.01 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.1 | 0.9795 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 50-2.05 (2.09-2.05) | 50.0-2.15 (2.19-2.15) |

| Z (molecules per ASU) | 1 | 2 |

| Rmerge (%)b | 8.1 (63.9) | 7.7 (48.5) |

| Mean I/σ | 52.7 (5.5) | 49.7 (6.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) |

| Redundancy | 24.7 (23.3) | 14.2 (14.7) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 41.28-2.05 | 44.65-2.15 |

| Rwork (%) | 17.51 | 19.71 |

| Rfree (%) | 19.70 | 24.38 |

| RMSD bond length (Å) | 0.008 | 0.003 |

| RMSD bond angle (°) | 1.115 | 0.692 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored (%) | 97.87 | 98.57 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.22 | 1.43 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PDB code | 4G9Y | 4FHT |

aHighest resolution shell data are shown in parentheses.

bRmerge = ΣhklΣi |Ii(hkl) − <I(hkl)>|/ ΣhklΣiIi(hkl) where Ii(hkl) is the ith observation of a symmetry equivalent reflection hkl.

Construction of Streptomyces mutant strains

The WT pcaV, pcaV R15A and pcaV R15K genes were cloned into the integrative constitutive expression vector pIJ10257 (40), yielding pJS368, pJS369 and pJS370, respectively. The resulting plasmids were transformed into ET12567/pUZ8002 (41), a non-methylating strain of E. coli, and introduced into the S. coelicolor ΔpcaV::apr (B760) strain through conjugation. Exconjugants containing pJS368, pJS369 or pJS370 were selected for by hygromycin resistance, yielding S. coelicolor B792, B793 and B794 strains, respectively.

Transcriptional analysis of pcaV mutant strains

Shaken liquid cultures of WT S. coelicolor, the pcaV null strain and pcaV null strains expressing genes encoding PcaV, PcaV R15A or PcaV R15K were grown for 16 h, after which RNA was isolated and quantified as previously discussed. The pcaV null strain expressing PcaV R15K was also grown in the presence of 2 mM PCA for 1 h before RNA was isolated at 16 h. Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCR) were accomplished using the OneStep RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. A 314-bp cDNA corresponding to the pcaH (SCO6700) transcript and a 486-bp cDNA corresponding to the hrdB (SCO5820) transcript were detected using the pcaH RT-PCR and hrdB RT-PCR primers, respectively. All primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The PCR program used for detection of transcripts was 50°C for 30 min, 95°C for 15 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s and 72°C for 60 s, followed by an elongation time of 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were detected on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Pfu polymerase was used to confirm the absence of contaminating DNA in RNA samples using the same cycling conditions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

PcaV binds two operator sites in the pcaV–pcaI intergenic region

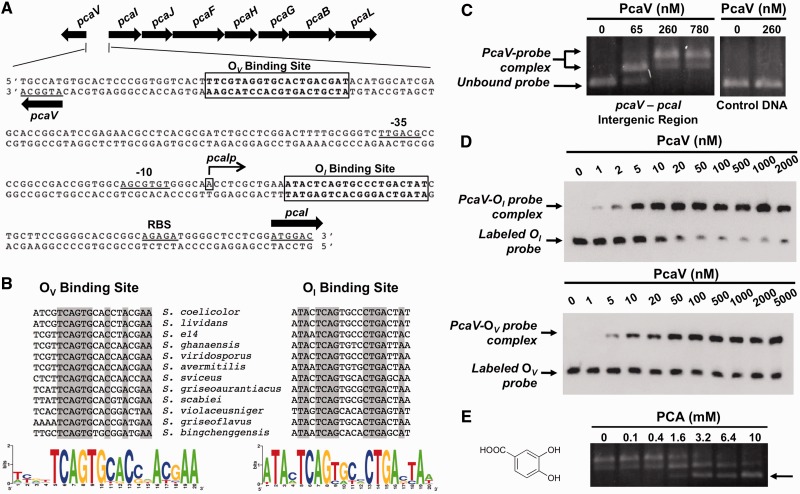

We previously reported that transcription of the pca structural genes in WT S. coelicolor is induced by PCA and de-repressed in a pcaV null strain (14). The latter observation shows that the pcaV gene product is a transcriptional repressor. By analogy to other repressors in the MarR family, we hypothesized that the molecular mechanism of transcriptional regulation would involve the binding of PcaV to a palindromic sequence near the transcription start site of the pca operon. To test this model, we used 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) analysis to map the transcription initiation of the pca operon to a site 69 bp upstream of the translational start site of pcaI (the first gene in the operon) (Figure 1A). Subsequently, using the Gibbs motif sampler (31) to search for palindromic sequences in the vicinity of the transcription start site, we identified two different 20-bp sites containing inverted repeat sequences in the pcaV–pcaI intergenic region (Figure 1A). We named the inverted repeat sequence that is proximal to the pcaI translational start site OI, which is 10 bp downstream of the transcriptional start site of pcaI, and the sequence closest to pcaV OV, which is 20 bp upstream of the pcaV translation start site. The two putative operators have different sequences but share some homology (Figure 1A). The OI site contains perfect inverted repeat sequences that are separated by 4 bp (TCAGxxxxCTGA). In contrast, the putative operator of pcaV has an imperfect inverted repeat sequence (TCAGTGxxCxxA). Both Gibbs motif sampler analyses and sequence alignments of the intergenic regions revealed that both inverted repeat sequences are conserved in the pca loci of multiple Streptomyces species (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the sequences are conserved even in S. scabies, where the pcaIJF genes are missing from the operon and the pcaV gene is divergently transcribed from pcaH.

Figure 1.

PcaV recognizes two operator sites in the pcaV–pcaI intergenic region. (A) The organization of the pca operon in S. coelicolor is depicted with the gene names above the arrows. The pcaV–pcaI intergenic sequence shows the PcaV operator sites (boxed), the transcriptional start site of pcaI (denoted as pcaIp), putative -35 and -10 pcaI promoter elements and a putative ribosome binding site (RBS). (B) Full sequence alignment of PcaV operator sites identified in the Streptomyces genus through the Gibbs Motif Sampler. Conserved nucleotides are highlighted in gray. Sequence logo images depict the sequence conservation of PcaV operator sites. (C) Agarose EMSA experiments using a PCR-amplified DNA probe spanning the pcaV–pcaI intergenic region and increasing concentrations of PcaV. In comparison with the unbound DNA probe in the electrophoresis, retarded migration of the DNA probe was observed on addition of PcaV. The formation of the PcaV–probe complex is indicated by a double arrow, whereas the unbound DNA is indicated with a single arrow. The control DNA probe spans a region of the pcaH open reading frame and does not contain PcaV operator sites. (D) Representative quantitative EMSA experiments using PCR-amplified biotin-labeled probes containing the OI site (top) or OV site (bottom) and increasing concentrations of PcaV. A single shifted band corresponding to the PcaV–probe complex is observed. Experiments were performed in triplicate to calculate dissociation constants (Kd). (E) Agarose EMSA experiments using PcaV bound to the pcaV–pcaI intergenic probe and increasing concentrations of protocatechuate. The dissociation of PcaV from the DNA is observed on addition of increasing amounts of protocatechuate. The unbound DNA is indicated with a single arrow. The structure of the PCA ligand is shown on the left.

To prove that PcaV binds DNA, purified PcaV was used in EMSAs containing a 209-bp PCR product spanning the entire pcaV–pcaI intergenic region in S. coelicolor. Titration with increasing quantities of PcaV resulted in a shift in the migration of the DNA probe (Figure 1C). Consistent with the sequence conservation of pca loci among streptomycetes, we found that the S. coelicolor PcaV also bound DNA probes spanning the pcaV–pcaI and the pcaV–pcaH intergenic regions of S. avermitilis and S. scabiei, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1A). Further, we observed two sets of shifted protein–DNA complexes in the EMSAs, which is consistent with our identification of two pseudopalindromic sites in the intergenic region. To evaluate the binding of PcaV to each of the pseudopalindromic sites, we PCR-amplified 100-bp biotinylated DNA probes containing either 20-bp site and used them in quantitative EMSAs with PcaV (Figure 1D). PcaV bound to each of the probes and only one shifted species was observed in each case, demonstrating that both operator sequences are bona fide PcaV-binding sites. From these experiments, we also calculated dissociation constants (Kd) of 4.6 ± 0.2 nM and 11.9 ± 1.4 nM for the OI and OV sites, respectively. These apparent Kd values are typical of other MarR family members and are consistent with a repressive model for transcriptional regulation (19,42,43). These data also show that PcaV binds the perfect palindrome, OI, more tightly than the imperfect palindrome, OV. To further demonstrate the binding specificity of PcaV to the operator sites, similar results were obtained using 30-bp biotinylated DNA probes containing either OI or OV (Supplementary Figure S1B). Thus, these results suggest that PcaV represses the transcription of not only the pca structural genes but also pcaV itself, consistent with the observation that more than half of the characterized MarR homologues regulate their own transcription (29).

PCA, the physiologically relevant ligand of PcaV, disrupts the PcaV–DNA complex

The fact that PCA is an inducer of the pca structural genes is significant because its catabolism is catalyzed by the pca gene products. As MarR family members typically regulate transcription through ligand-mediated attenuation of DNA binding (22), we predicted that PCA would reduce the affinity of PcaV for the operators (OI and OV) in the pcaV–pcaI intergenic region. Titration of pre-formed PcaV–DNA complexes with increasing amounts of PCA induced dissociation of PcaV from the pcaV–pcaI intergenic DNA in EMSAs (Figure 1E). The PCA-promoted dissociation of the PcaV–DNA complex is one of a few known examples in which the capacity of a MarR family member to regulate a catabolic pathway is mediated by direct association with a substrate of the pathway (20,44–46). Then, we used ITC to determine the PcaV–PCA stoichiometry and the affinity of PcaV for PCA (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure S2A). The stoichiometry of the complex is 1:1 (monomer:ligand), and the calculated dissociation constant was 668 ± 2.6 nM (Table 2), reflecting one of the highest affinities ever reported for a MarR–ligand interaction (29). Together, these observations show that the transcription of the pca catabolic genes is induced by the cognate substrate (PCA) of the encoded enzymes.

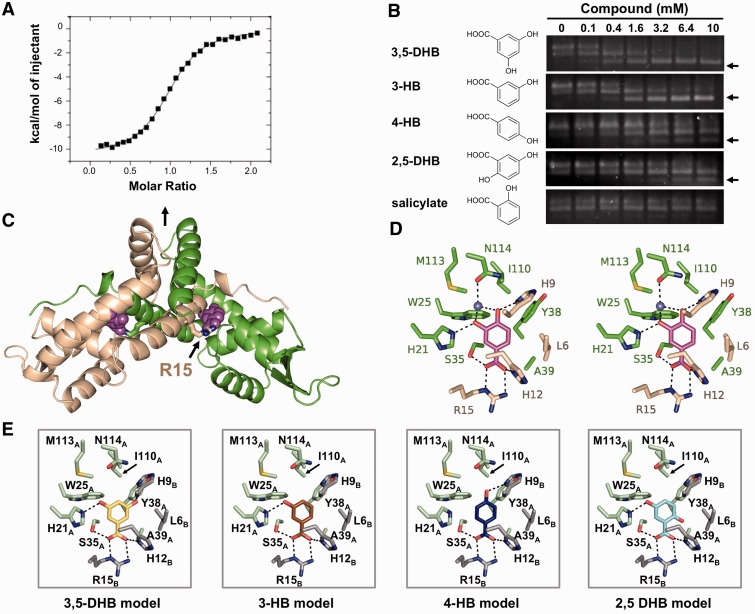

Figure 2.

The structure of PcaV bound to its ligand protocatechuate. (A) Representative binding isotherm of PCA titrated into WT PcaV. Raw data are shown in Supplementary Figure S2A. (B) EMSAs of PcaV–DNA complex in the presence of increasing amounts of the indicated ligands. Unbound DNA is indicated with an arrow. (C) The crystal structure of the PcaV–PCA complex. The PcaV dimer is shown as a ribbon representation, with one monomer in green and the second monomer in beige. The two-fold dimer interface is denoted with a vertical black arrow. The bound PCA ligands (magenta spheres) bind in symmetrical pockets buried between helices α1, α2 and α5 from one monomer and helix α1 from the second monomer; Arg15 is shown in stick representation. (D) Stereo image of the protocatechuate (colored in magenta) binding pocket; residues from both PcaV monomers are shown as sticks (colored as in C). Polar contacts are shown as dashed lines; the light blue sphere is a water molecule. (E) Models of the putative PcaV–ligand interactions from (B). Each model was generated through superposition onto the PCA molecule in the PcaV–PCA crystal structure. Potential polar interactions are shown as dashed lines.

Table 2.

Hydroxybenzoate ligand dissociation constants

| Ligand | Abbreviation | PcaV | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protocatechuate | PCA | WT | 0.67 ± < 0.01 |

| 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate | 3,5-DHB | WT | 4.34 ± 0.52 |

| 3-hydroxybenzoate | 3-HB | WT | 5.91 ± 0.54 |

| 4-hydroxybenzoate | 4-HB | WT | 141.25 ± 1.41 |

| 2,5-dihydroxybenzoate | 2,5-HB | WT | 146.86 ± 1.83 |

| Protocatechuate | PCA | R15A | No binding |

| Protocatechuate | PCA | R15K | No binding |

Phenolic compounds differentially bind PcaV and affect its ability to bind DNA

MarR family members exhibit promiscuity in ligand binding (17,20,21,29,45–53). For example, the ligands of EmrR, a MarR family member that regulates expression of a multi-drug resistance pump in E. coli, are certain antibiotics, protonophores, 2,4-dinitrophenol and salicylate (21,50). While the PcaV-mediated transcriptional response of S. coelicolor to PCA can be explained by its catabolism, we were interested in determining if PcaV could respond to any other ligands. We performed EMSAs in the presence of multiple catabolites and phenolic compounds, including β-ketoadipate, salicylate (2-hydroxybenzoate), catechol, vanillate, benzoate and six different hydroxylated benzoates. β-ketoadipate, a ligand regulator of the β-ketoadipate pathway genes in other organisms (4), did not affect the stability of the PcaV–DNA complex (Supplementary Figure S3A). Likewise, we found that catechol, vanillate and benzoate did not affect stability of the PcaV–DNA complex, as evidenced by the absence of free DNA in the titration EMSAs (Supplementary Figure S3A). Similar results were obtained for two of the six hydroxylated benzoates (2,3-dihydroxybenzoate and 2,4-dihydroxybenzoate, Supplementary Figure S3A). Unexpectedly, despite the fact that salicylate is a phenolic ligand of many characterized MarR family members (17,43,54–56), addition of up to 10 mM salicylate was also unable to disrupt the PcaV–DNA complex (Figure 2B).

In contrast, certain phenolic compounds, including 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate (3,5-DHB), 3-hydroxybenzoate (3-HB), 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HB) and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoate (2,5-DHB), promoted the dissociation of PcaV from its cognate DNA (Figure 2B). The in vitro observations were corroborated by RT-PCR analyses, wherein transcripts of pca structural genes were detected in S. coelicolor cultures grown in media supplemented with 2 mM of the phenolic compounds (Supplementary Figure S3B). This demonstrates that PcaV, like other MarR proteins, can bind multiple structurally related ligands (20,29,45,46,48,49,52). Subsequently, we used ITC to determine the affinities of the ligands for PcaV. While PcaV bound PCA most tightly, it bound the other phenolic compounds with either low micromolar dissociation constants (3,5-DHB, 3-HB) or high micromolar dissociation constants (4-HB, 2,5-DHB; Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S2). The preference of PcaV for PCA is consistent with the fact that the ligand is catabolized by the products of genes whose expression is regulated by PcaV.

The structure of the PcaV–PCA complex is the first of a MarR family member bound to a substrate for catabolism

Several structures of MarR family members bound to ligands have been reported (17,54,55). With the exception of structures of TcaR in complex with different antibiotics (17), all reported structures have salicylate bound as ligand. Arguably, there are reasons to question the biological relevance of salicylate-bound structures (22). First, the number and location of salicylate-binding sites varies significantly between MarR family members. Second, many MarR proteins display a low affinity for salicylate, with reported dissociation constants in the millimolar range (i.e., as much as 1000-fold higher than the Kd for the PcaV–PCA interaction) (47,48,51,55). The fact that PCA is the physiologically relevant ligand of PcaV and binds with high affinity motivated structural studies. Accordingly, we determined the crystal structures of apo-PcaV and the PcaV–PCA complex to 2.05 Å and 2.15 Å resolution, respectively (Table 1).

PcaV is a dimer that adopts the canonical fold characteristic of the MarR family of transcriptional regulators (α1-α2-β1-α3-α4-β2-W1-β3-α5-α6 topology, Supplementary Figure S4A; the PcaV secondary structural assignment is provided in Supplementary Table S3). Helices α1, α5 and α6 from each monomer form the dimerization interface, burying ∼4913 Å2 of solvent accessible surface area, in an interaction that is largely hydrophobic. Extending away from the dimerization interface is the winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) motif, where helix α4 and the loop between β-strands β2 and β3 (W1) form the DNA interaction surface. Apo-PcaV is a crystallographic dimer (Supplementary Figure S4A), whereas PcaV bound to PCA is a non-crystallographic dimer (Figure 2C).

As deduced from our ITC studies, PCA binds PcaV in a 1:1 ratio. The two molecules of PCA bind PcaV in two deep symmetry-related pockets at the dimerization interface, where each ligand interacts with residues from both monomers (Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure S4B-C). The PCA binding pocket includes His21A, Trp25A, Ser35A, Tyr38A, Ala39A, Ile110A, Met113A and Asn114A from monomer A and Leu6B, His9B, Gly11B, His12B, and Arg15B from monomer B (Figure 2D). The most prominent protein–ligand interaction is a bidentate salt bridge between the guanadinium group of Arg15B in helix α1 and the carboxylate moiety of PCA. Additional polar interactions include hydrogen bonds between the PCA 4-hydroxyl and His9B and the PCA 3-hydroxyl and His21A. Finally, residue Asn114A positions a water molecule that also interacts with both the 3-hydroxyl and 4-hydroxyl of PCA. The remaining residues interact with PCA through hydrophobic contacts. As a consequence, the PCA molecule is completely occluded from solvent in the PcaV–PCA complex and is also well-ordered, with an average B-factor of 21.7 Å2. Although the PcaV monomers in the PcaV–PCA complex are not identical (Supplementary Figure S4D, there are small differences in the W1 loops of each monomer), equivalent interactions are observed for the second PCA ligand, and it is also well-ordered, with an average B-factor of 21.6 Å2.

With respect to ligand binding, the structures of other MarR family members in complex with salicylate have been more difficult to interpret than the PcaV–PCA structure. In those structures, multiple molecules of salicylate are bound to the dimer at both symmetry and non-symmetry related sites (17,55,56). Comparison of the PcaV–PCA complex with the SlyA–salicylate and MTH313–salicylate complexes revealed that one of the salicylates from both complexes binds in a pocket similar to the PCA-binding pocket in PcaV (Supplementary Figure S4E). In addition to interacting with multiple hydrophobic residues from both monomers, the carboxylate moieties of the bound salicylates are also coordinated by an Arg residue from helix α1. The similar ligand-binding environment at this pocket suggests that these proteins have evolved the ability to coordinate distinct anionic phenolic ligands.

Structure of the PcaV–PCA complex explains the ligand specificity of PcaV

The structure of the PcaV–PCA complex enabled us to rationalize the differential affinities of PcaV for the various phenolic compounds (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figure S2). Like PCA, the phenolic compounds that interact strongly with PcaV have a 3-hydroxyl group (substituted at the meta position) that forms a hydrogen bond with His21. In contrast, derivatives without a hydroxyl group in this position cannot form a hydrogen bond with this residue and therefore interact more weakly with PcaV. Moreover, the presence of a second hydroxyl substituent at either the 4-position (PCA) or 5-position (3,5-DHB), both of which result in an additional hydrogen bond with His9, increases the binding affinity by 8.8- and 1.4-fold, respectively. Finally, the presence of a second hydroxyl substituent at the 2-position (substituted at the ortho position) significantly reduces the affinity by > 200-fold (2,5-DHB) or abolishes binding altogether (2,4-DHB and 2,3-DHB, Supplementary Figure S3A), suggesting that there may be a conformational rearrangement of the ligand-binding pocket in the presence of compounds containing hydroxyl groups at the 2-position. Collectively, these structure-based models and biochemical data show that PcaV exhibits ligand specificity based primarily by hydrogen bonding with the hydroxyl groups of the phenolic compounds, where the meta substitution is a positive determinant of ligand binding and the ortho substitution is a negative determinant. The only compound with a 2-hydroxyl group that bound PcaV (2,5-DHB) did so due to the presence of a favorable meta-hydroxyl substituent. PcaV exhibits a high degree of selectivity for ligand binding to regulate gene transcription.

PCA stabilizes a conformation of PcaV incompatible with DNA binding

To understand how ligand binding alters the PcaV conformation, we compared the apo and ligand-bound PcaV structures (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S5). Using the sieve_fit algorithm (57), we first identified the residues in the dimerization domain that are structurally conserved between the apo- and ligand-bound states. This dimerization ‘core’ is composed of residues Leu13-Gln19 and Gln115-Arg134 from both monomers, which superimpose with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.43 Å (Supplementary Figure S5B). The presence of a dimerization core shows that this interface is structurally conserved between the apo- and ligand-bound states. Similar comparisons of the wHTH domains from both structures revealed that they also form a rigid body, with the wHTH core composed of residues Val29-Arg83 and Ser91-Ala111 (wHTH cores superimpose with RMSDs of ∼0.4 Å; Supplementary Figure S5B).

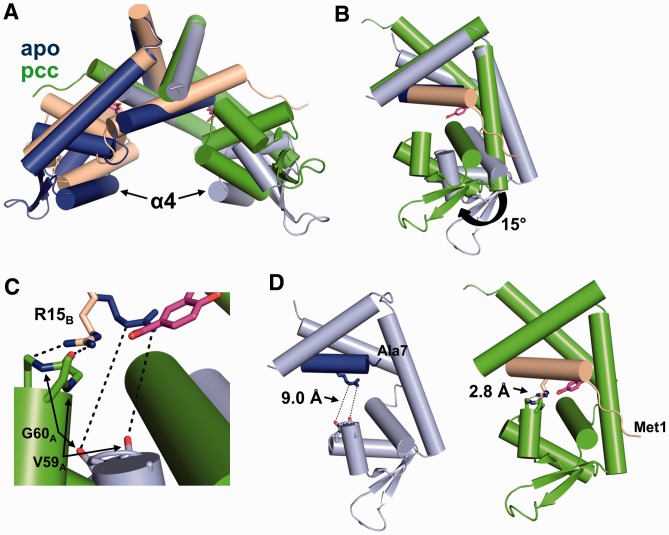

Figure 3.

Ligand binding induces significant conformational changes in PcaV. (A) Secondary structure superposition of the apo-Pcav dimer (colored in light blue and dark blue) and the PcaV–PCA dimer (colored as in Figure 2). (B) Superposition of the dimerization core of one monomer of apo-PcaV and ligand-bound PcaV (colored as in A). The PcaV wHTH domain rotates up 15° towards helix α1 of the opposite monomer on ligand binding to form the PCA-binding pocket. (C) Zoomed-in view of the interactions between Arg15 (shown as stick representation in blue and beige for apo- and ligand-bound PcaV, respectively) and the backbone carbonyl groups from Val59 and Gly60 from the opposite monomer (apo-PcaV in light blue and ligand-bound PcaV in green). (D) Orientation of Arg15B relative to Val59A and Gly60A in the apo (left panel) and PCA-bound (right panel) structures. In apo-PcaV, Arg15B is 9 Å away from the loop preceding helix α4 of the opposite monomer. Rotation of the wHTH domain on ligand-binding brings Arg15B in close proximity to the Val59A-Gly60A loop, forming polar interactions that stabilize the ligand-bound conformation.

Superposition of the apo-PcaV and PcaV–PCA complexes through the dimerization core reveals that ligand binding induces a significant conformational change in PcaV (Figure 3A). Specifically, PCA binding causes the wHTH domains to rotate up towards the dimerization interface by nearly 15° (Figure 3B). This interaction is stabilized by Arg15, which interacts not only with the bound PCA ligand but also forms two hydrogen bonds with the backbone carbonyls of wHTH residues Val59 and Gly60 (Figure 3C). The position of the wHTH domain is further stabilized by the N-terminal residues of PcaV, which are disordered in the apo state but become ordered in the presence of PCA. The rotation of the wHTH domain and the ordering of the N-terminal region of PcaV form a buried binding pocket for PCA, over which the N-terminal residues form a ‘lid’ (Figure 3D). Remarkably, residues of the apo structure move by >5 Å to form the ligand-binding pocket.

Arg15 is a determinant for both ligand and DNA binding

In the PcaV–PCA complex, Arg15 forms the base of the ligand-binding pocket and neutralizes the buried negative charge of the PCA ligand. To determine the functional importance of Arg15 in ligand binding, we used site-directed mutagenesis of pcaV to generate a protein in which this residue was substituted with either a similarly charged lysine (PcaV R15K) or an alanine (PcaV R15A). We verified that these substitutions did not affect the fold or stability of PcaV (Supplementary Figure S6A and B) and then tested their abilities to bind PCA using ITC (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S6C). We found that neither PcaV R15A nor PcaV R15K bound PCA, even up to concentrations as high as 1.5 mM, which is 2000-fold higher than the affinity of WT PcaV for PCA (Table 2). These observations are consistent with our prediction that the guanidinium moiety of Arg15 is essential for binding PCA.

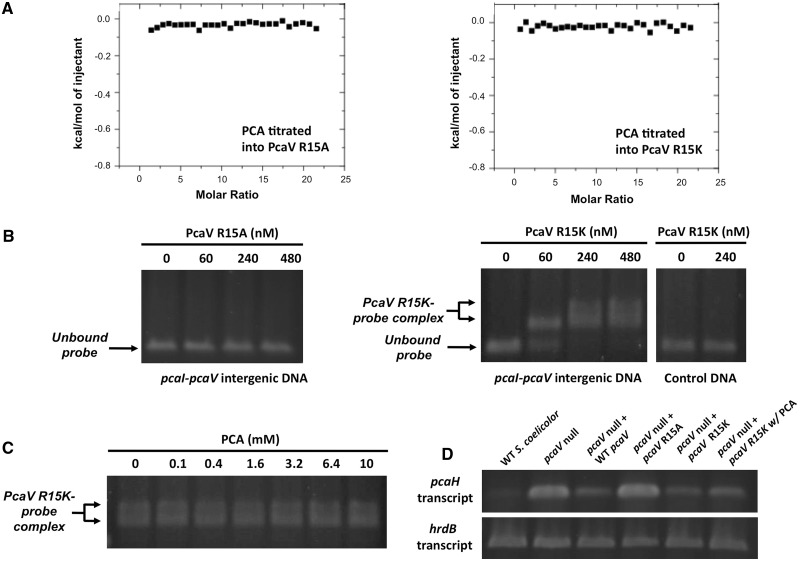

Figure 4.

PcaV Arg15 is a critical determinant for both ligand and DNA binding. (A) Representative binding isotherm of PCA titrated into PcaV R15A and PcaV R15K. Raw data are shown in Supplementary Figure S6C. (B) Agarose EMSA experiments using a PCR-amplified DNA probe spanning the pcaV–pcaI intergenic region and increasing concentrations of either PcaV R15A or R15K. In comparison with the unbound DNA probe in the electrophoresis, retarded migration of the DNA probe was observed on addition of PcaV R15K but not PcaV R15A. The formation of the PcaV R15K–probe complex is indicated by a double arrow, whereas the unbound DNA is indicated with a single arrow. The control DNA probe spans a region of the pcaH open reading frame that does not contain PcaV operator sites. (C) Agarose EMSA experiments using PcaV R15K bound to the pcaV–pcaI intergenic probe and increasing concentrations of protocatechuate. No dissociation of PcaV R15K from the DNA is observed on addition of increasing amounts of protocatechuate. (D) Reverse transcription PCR analyses of the pcaH gene in WT S. coelicolor, the pcaV null strain and pcaV null strains expressing genes encoding PcaV, PcaV R15A, or PcaV R15K under the control of the constitutive promoter (ermEp*) from pIJ10257. As previously reported, transcription of the pcaH gene is not repressed in the pcaV null strain. This transcriptional defect is suppressed in pcaV null strains over-expressing genes encoding either PcaV or PcaV R15K, but not in a strain producing PcaV R15A. Addition of protocatechuate to the pcaV null strain producing PcaV R15K did not induce transcription of the pcaH gene. The hrdB gene, which encodes a vegetative sigma factor, was used as a control and is constitutively transcribed in all samples.

To determine the potential role of PcaV Arg15 in DNA binding, we performed EMSAs with the pcaV–pcaI intergenic region and increasing quantities of either PcaV R15A or PcaV R15K (Figure 4B). Interestingly, we discovered that the PcaV R15A mutant could not bind DNA, even at concentrations up to 100-fold higher than the dissociation constant of WT PcaV for OI. In contrast, PcaV R15K did bind DNA in the EMSAs (Figure 4B), indicating that a cationic residue at position 15 is necessary and sufficient for DNA binding. However, the complex between this protein and DNA did not dissociate even in the presence of 10 mM PCA (Figure 4C). The finding that the PcaV R15K-DNA complex is not responsive to PCA is consistent with the ITC analysis (Figure 4A). To corroborate the findings of the in vitro analyses, we examined the expression of a pcaV-dependent structural gene (pcaH) in a pcaV null strain in which genes encoding either PcaV R15A or PcaV R15K were ectopically expressed. As expected, we found that the former strain could not repress pcaH transcription, whereas pcaH transcription could not be de-repressed by PCA in the latter (Figure 4D). Like PcaV, other MarR family members also have an arginine residue in helix α1 that is critical for DNA binding. For instance, substitution of an arginine residue in helix α1 of MexR with a tryptophan residue ablates DNA binding (58,59). However, this is the first time that a single residue, PcaV Arg15, in a MarR family member has been shown to be critical for both ligand and DNA binding.

The mutually exclusive binding of PcaV to PCA and DNA, and the essential role of Arg15 in both of these interactions, calls for attention to the role of this residue in the function of the transcriptional repressor. As is the case for PcaV, many MarR proteins have an arginine in helix α1 that either complexes bound ligand (SlyA Arg14; MTH313 Arg16) and/or defines the orientation of the wHTH domain in the presence of DNA (SlyA Arg14) (55,56). We used DALI to identify MarR family members whose structures are most similar to PcaV and conservatively identified structurally analogous arginine residues in ∼50% of these proteins (Supplementary Table S4). In nearly all MarR structures bound with an anionic ligand (i.e., salicylate) and in the PcaV–PCA structure, this arginine interacts directly with the ligand. Interestingly, this arginine is also conserved in members of other MarR sub-families that do not bind anionic ligands, including those regulated by oxidation, which may suggest a DNA-binding function. Our studies of PcaV demonstrate the importance of an arginine in helix α1 for both ligand and DNA binding. By extension, we anticipate that analogous arginines in other MarR family members play similar roles in ligand and/or DNA binding.

We compared both the salicylate- (PDB 3DEU, unpublished) and DNA-bound structures of SlyA (PDB 3Q5F) (56) to PcaV in an effort to explain why Arg15 is so important for both functions of the transcriptional repressor. In the SlyA-DNA structure, Arg14 interacts with the backbone carbonyl of Gly57 in the wHTH domain through hydrogen bonds. This residue is located in the loop immediately preceding the conserved DNA-binding helix α4. In the structure of the SlyA-salicylate complex, Arg14 is engaged in hydrogen bonds with the carboxylate moiety of the bound ligand (Supplementary Figure S4E) and the carbonyl of the wHTH residue Ile56. Apparently, ligand-binding changes the backbone interactions of Arg14, which in turn induces a small rotation of the SlyA wHTH domain relative to the dimerization domain that prevents DNA binding. In analogy to Arg14 of the SlyA-ligand complex, Arg15 in PcaV is engaged in hydrogen bonds with the ligand and with the backbone carbonyls of residues of the opposing monomer wHTH domain (Val59 and Gly60; Figure 3C), favoring an orientation of the wHTH domains incapable of binding DNA. Presumably, Arg15 is engaged in a different set of backbone interactions with the wHTH domain when PcaV is bound to DNA, as is the case for SlyA. These backbone interactions with Arg15 must be critically important because the R15A mutant of PcaV does not bind DNA. Based on our findings, we propose that Arg15 functions as a ‘gatekeeper’ residue that stabilizes conformations of PcaV that are either permissive or non-permissive for DNA binding in a manner dictated by its interaction with ligand.

CONCLUSIONS

There is growing interest in harnessing bacteria for bioremediation, alternative energy and the production of commodity chemicals which requires a molecular understanding of how these metabolic pathways are regulated. Here, we have shown that PcaV, a transcription factor in the MarR family, is regulated by the lignin-derived compound PCA, which is the aromatic precursor of the metabolic pathway controlled by the pca gene products in S. coelicolor. We also demonstrate that PcaV functions as a transcriptional repressor and interacts strongly with PCA, with a Kd of 668 nM, which disrupts its interaction with the pca intergenic region. The structures of the apo- and PCA-bound PcaV and detailed structure activity studies with PCA analogs also revealed that PcaV exhibits an unusually high degree of ligand selectivity and is one of few MarR homologues incapable of binding salicylate. Most importantly, we show that Arg15, which is critical for coordinating the PCA ligand, also plays an equally critical role in binding DNA and thus functions as a gatekeeper residue for regulating PcaV transcriptional activity. Because this residue is not only structurally conserved, but also has been observed to coordinate ligands and DNA in multiple MarR homologues, we predict that this arginine plays an analogous role in many members of the MarR family of transcriptional regulators. This work provides novel insights into the molecular mechanism of transcriptional repression of MarR family members and ligand-mediated attenuation of DNA binding.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID codes 4G9Y and 4FHT).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables 1–4, Supplementary Figures 1–6 and Supplementary Methods.

FUNDING

National Science Foundation CAREER awards [MCB-0952550 to R.P. and MCB-1053319 to J.K.S]; a National Science Foundation research initiation [MCB-09020713 to J.K.S.]; a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (to J.R.D); a National Institute of Health NRSA F31 fellowship [NS062630 to B.L.B.]. J.K.S. and R.P. also acknowledge a Seed award from the Office of Vice President for Research at Brown University. Data for this study were measured at beamline X25 of the National Synchrotron Light Source (supported principally by the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy, and from the National Center for Research Resources (P41RR012408) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41GM103473) of the National Institutes of Health. This research is based in part on work conducted using the Rhode Island NSF/EPSCoR Proteomics Share Resource Facility, which is supported in part by the National Science Foundation EPSCoR [1004057]; National Institutes of Health [1S10RR020923]; Rhode Island Science and Technology Advisory Council grant; Division of Biology and Medicine, Brown University. Funding for open access charge: Brown University.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Prof. Charles Lawrence, Dr. William Thompson and Dr. Lee Ann McCue for assistance in bioinformatic analyses and Prof. Wolfgang Peti for technical advice on ITC and for use of equipment. Antoni Tortajada is gratefully acknowledged for assisting with protein purification.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fuchs G, Boll M, Heider J. Microbial degradation of aromatic compounds - from one strategy to four. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:803–816. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masai E, Katayama Y, Fukuda M. Genetic and biochemical investigations on bacterial catabolic pathways for lignin-derived aromatic compounds. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007;71:1–15. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin EM. Genomics of cellulosic biofuels. Nature. 2008;454:841–845. doi: 10.1038/nature07190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harwood CS, Parales RE. The beta-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1996;50:553–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosa M, Ragauskas AJ. Bioconversion of lignin model compounds with oleaginous Rhodococci. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;93:891–900. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3743-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleichrodt FS, Fischer R, Gerischer UC. The beta-ketoadipate pathway of Acinetobacter baylyi undergoes carbon catabolite repression, cross-regulation and vertical regulation, and is affected by CRC. Microbiology. 2010;156:1313–1322. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkrolf K, Brune I, Tauch A. Transcriptional regulation of catabolic pathways for aromatic compounds in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Genet. Mol. Res. 2006;5:773–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brzostowicz PC, Reams AB, Clark TJ, Neidle EL. Transcriptional cross-regulation of the catechol and protocatechuate branches of the beta-ketoadipate pathway contributes to carbon source-dependent expression of the Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 pobA gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:1598–1606. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1598-1606.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li D, Yan Y, Ping S, Chen M, Zhang W, Li L, Lin W, Geng L, Liu W, Lu W, et al. Genome-wide investigation and functional characterization of the beta-ketoadipate pathway in the nitrogen-fixing and root-associated bacterium Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao KX, Huang Y, Chen X, Wang NX, Liu SJ. PcaO positively regulates pcaHG of the beta-ketoadipate pathway in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:1565–1572. doi: 10.1128/JB.01338-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLean AM, MacPherson G, Aneja P, Finan TM. Characterization of the beta-ketoadipate pathway in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:5403–5413. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00580-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siehler SY, Dal S, Fischer R, Patz P, Gerischer U. Multiple-level regulation of genes for protocatechuate degradation in Acinetobacter baylyi includes cross-regulation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:232–242. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01608-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parke D. Characterization of PcaQ, a LysR-type transcriptional activator required for catabolism of phenolic compounds, from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:266–272. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.266-272.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis JR, Sello JK. Regulation of genes in Streptomyces bacteria required for catabolism of lignin-derived aromatic compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;86:921–929. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vesely M, Knoppova M, Nesvera J, Patek M. Analysis of catRABC operon for catechol degradation from phenol-degrading Rhodococcus erythropolis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007;76:159–168. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tropel D, van der Meer JR. Bacterial transcriptional regulators for degradation pathways of aromatic compounds. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:474–500. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.474-500.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang YM, Jeng WY, Ko TP, Yeh YJ, Chen CK, Wang AH. Structural study of TcaR and its complexes with multiple antibiotics from Staphylococcus epidermidis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:8617–8622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913302107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Fiore A, Fiorentino G, Vitale RM, Ronca R, Amodeo P, Pedone C, Bartolucci S, De Simone G. Structural analysis of BldR from Sulfolobus solfataricus provides insights into the molecular basis of transcriptional activation in Archaea by MarR family proteins. J Mol. Biol. 2009;388:559–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuangthong M, Atichartpongkul S, Mongkolsuk S, Helmann JD. OhrR is a repressor of ohrA, a key organic hydroperoxide resistance determinant in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:4134–4141. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4134-4141.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasai D, Kamimura N, Tani K, Umeda S, Abe T, Fukuda M, Masai E. Characterization of FerC, a MarR-type transcriptional regulator, involved in transcriptional regulation of the ferulate catabolic operon in Sphingobium sp. strain SYK-6. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012;332:68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomovskaya O, Lewis K, Matin A. EmrR is a negative regulator of the Escherichia coli multidrug resistance pump EmrAB. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:2328–2334. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2328-2334.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perera IC, Grove A. Molecular mechanisms of ligand-mediated attenuation of DNA binding by MarR family transcriptional regulators. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;2:243–254. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antelmann H, Helmann JD. Thiol-based redox switches and gene regulation. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2011;14:1049–1063. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brugarolas P, Movahedzadeh F, Wang Y, Zhang N, Bartek IL, Gao YN, Voskuil MI, Franzblau SG, He C. The oxidation-sensing regulator (MosR) is a new redox-dependent transcription factor in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:37703–37712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.388611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong M, Fuangthong M, Helmann JD, Brennan RG. Structure of an OhrR-ohrA operator complex reveals the DNA binding mechanism of the MarR family. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palm GJ, Khanh Chi B, Waack P, Gronau K, Becher D, Albrecht D, Hinrichs W, Read RJ, Antelmann H. Structural insights into the redox-switch mechanism of the MarR/DUF24-type regulator HypR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4178–4192. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poor CB, Chen PR, Duguid E, Rice PA, He C. Crystal structures of the reduced, sulfenic acid, and mixed disulfide forms of SarZ, a redox active global regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:23517–23524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.015826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holley TA, Stevenson CE, Bibb MJ, Lawson DM. High resolution crystal structure of SCO5413, a widespread actinomycete MarR family transcriptional regulator of unknown function. Proteins. 2013;81:176–182. doi: 10.1002/prot.24197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson SP, Grove A. Ligand-responsive transcriptional regulation by members of the MarR family of winged helix proteins. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2006;8:51–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. Norwich, England: John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson W, Rouchka EC, Lawrence CE. Gibbs Recursive Sampler: finding transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3580–3585. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markowitz VM, Korzeniewski F, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Werner G, Padki A, Zhao X, Dubchak I, Hugenholtz P, Anderson I, et al. The integrated microbial genomes (IMG) system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D344–D348. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turnbull WB, Daranas AH. On the value of c: can low affinity systems be studied by isothermal titration calorimetry? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14859–14866. doi: 10.1021/ja036166s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In: Carter CW Jr, Sweet RM, editors. Macromolecular Crystallography, part A. Vol. 276. New York: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaroszewski L, Rychlewski L, Li Z, Li W, Godzik A. FFAS03: a server for profile–profile sequence alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W284–W288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong HJ, Hutchings MI, Hill LM, Buttner MJ. The role of the novel Fem protein VanK in vancomycin resistance in Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13055–13061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gust B, Challis GL, Fowler K, Kieser T, Chater KF. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1541–1546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337542100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkinson SP, Grove A. HucR, a novel uric acid-responsive member of the MarR family of transcriptional regulators from Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:51442–51450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin RG, Rosner JL. Binding of purified multiple antibiotic-resistance repressor protein (MarR) to mar operator sequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:5456–5460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirakawa H, Schaefer AL, Greenberg EP, Harwood CS. Anaerobic p-coumarate degradation by Rhodopseudomonas palustris and identification of CouR, a MarR repressor protein that binds p-coumaroyl coenzyme A. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:1960–1967. doi: 10.1128/JB.06817-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Providenti MA, Wyndham RC. Identification and functional characterization of CbaR, a MarR-like modulator of the cbaABC-encoded chlorobenzoate catabolism pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:3530–3541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3530-3541.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshida M, Hiromoto T, Hosokawa K, Yamaguchi H, Fujiwara S. Ligand specificity of MobR, a transcriptional regulator for the 3-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase gene of Comamonas testosteroni KH122-3s. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;362:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Alteration of the repressor activity of MarR, the negative regulator of the Escherichia coli marRAB locus, by multiple chemicals in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:4669–4672. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4669-4672.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chubiz LM, Rao CV. Aromatic acid metabolites of Escherichia coli K-12 can induce the marRAB operon. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:4786–4789. doi: 10.1128/JB.00371-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galan B, Kolb A, Sanz JM, Garcia JL, Prieto MA. Molecular determinants of the hpa regulatory system of Escherichia coli: the HpaR repressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6598–6609. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiong A, Gottman A, Park C, Baetens M, Pandza S, Matin A. The EmrR protein represses the Escherichia coli emrRAB multidrug resistance operon by directly binding to its promoter region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2905–2907. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.10.2905-2907.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu L, Fang J, Wei Y. Characterization of the ligand and DNA binding properties of a putative archaeal regulator ST1710. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2099–2108. doi: 10.1021/bi801662s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parke D, Ornston LN. Hydroxycinnamate (hca) catabolic genes from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 are repressed by HcaR and are induced by hydroxycinnamoyl-coenzyme A thioesters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:5398–5409. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5398-5409.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumaraswami M, Schuman JT, Seo SM, Kaatz GW, Brennan RG. Structural and biochemical characterization of MepR, a multidrug binding transcription regulator of the Staphylococcus aureus multidrug efflux pump MepA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1211–1224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumarevel T, Tanaka T, Umehara T, Yokoyama S. ST1710-DNA complex crystal structure reveals the DNA binding mechanism of the MarR family of regulators. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4723–4735. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saridakis V, Shahinas D, Xu X, Christendat D. Structural insight on the mechanism of regulation of the MarR family of proteins: high-resolution crystal structure of a transcriptional repressor from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dolan KT, Duguid EM, He C. Crystal structures of SlyA protein, a master virulence regulator of Salmonella, in free and DNA-bound states. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:22178–22185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Page R, Lindberg U, Schutt CE. Domain motions in actin. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;280:463–474. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andresen C, Jalal S, Aili D, Wang Y, Islam S, Jarl A, Liedberg B, Wretlind B, Martensson LG, Sunnerhagen M. Critical biophysical properties in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa efflux gene regulator MexR are targeted by mutations conferring multidrug resistance. Protein Sci. 2010;19:680–692. doi: 10.1002/pro.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lim D, Poole K, Strynadka NC. Crystal structure of the MexR repressor of the mexRAB-oprM multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:29253–29259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.