Abstract

Sclerosing peritonitis is an uncommon complication of peritoneal dialysis. It is characterized by peritoneal fibrosis and sclerosis. The most common clinical presentations of sclerosing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients are ultrafiltration failure and small bowel obstruction. The prognosis and response to immunosuppressive therapy of sclerosing peritonitis presenting with ultrafiltration failure or small bowel obstruction are poor. Here, we describe the case of a 28-yr-old man with end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis showing fulminant sclerosing peritonitis presented like acute culture-negative peritonitis and was successfully treated with corticosteroid therapy. It is not well recognized that sclerosing peritonitis may present in this way. The correct diagnosis and corticosteroid therapy may be life-saving in a fulminant form of sclerosing peritonitis.

Keywords: Peritonitis, Peritoneal Sclerosis, Peritoneal Dialysis, Steroids

INTRODUCTION

Sclerosing peritonitis (SP) is a rare form of peritoneal inflammation which involves both the visceral and the parietal surfaces of the abdominal cavity. It is characterized by a fibrous thickening and sclerotic changes of the peritoneum and is reported to complicate peritoneal dialysis (PD) in most cases. The common clinical manifestations are ultrafiltration and clearance failure in PD patients. Furthermore, small bowel obstruction due to adhesions and encapsulation with abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting is frequently observed and ultimately entails weight loss and malnutrition. It has a poor response to immunosuppressive therapy (1, 2).

We describe the case of a 28-yr-old man with end-stage renal disease on PD showing fulminant SP presented like acute culture-negative peritonitis and successfully treated with corticosteroid therapy. On review of the literature, there have been only a few case reports where the presentation of SP has been dominated by an acute inflammatory state (3-7). There was a delay in diagnosis due to the rare mode of presentation, and also a delay in commencement of appropriate therapy. A high degree of clinical suspicion is necessary to diagnose this form of SP, and initiate corticosteroid therapy which appears particularly effective for fulminant SP (1, 7).

CASE DESCRIPTION

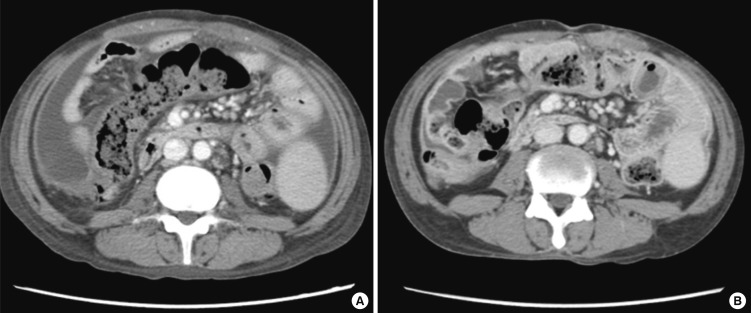

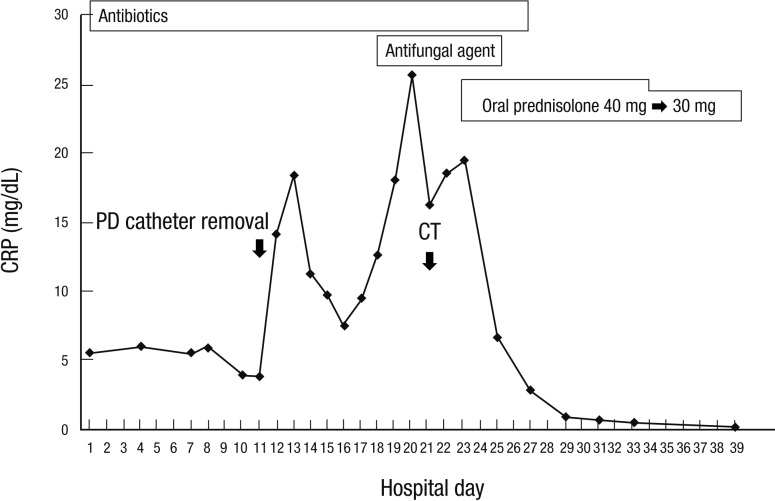

A 28-yr-old man had been maintained on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) for 6 yr due to end-stage renal disease of unknown etiology. He used Baxter CAPD system and dialysate with lactate as the base. In December 2011, he had first episode of uncomplicated peritonitis by methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus epidermidis, which was treated with intraperitoneal cefazolin. On April 06, 2012, he was admitted due to diffuse abdominal pain which had developed 5 days before admission. At the time of admission, blood pressure was 143/77 mmHg, body temperature 36.4℃, height 155 cm, and weight 39 kg. Physical examination showed decreased bowel sound and diffuse abdominal tenderness without rebound tenderness. Laboratory tests showed the following: hemoglobin 12.4 g/dL, hematocrit 35.6%, leukocyte count 8,540/µL with neutrophil 86.4%, platelet 219,000/µL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 5.17 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen 74.5 mg/dL, serum creatinine 16.59 mg/dL, glucose 184 mg/dL, cholesterol 181 mg/dL, total protein 8.2 g/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, AST 19 U/L, ALT 23 U/L, total bilirubin 0.42 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 258 IU/L, CK 96 U/L, LDH 411 U/L, amylase 7 U/L, lipase 42 U/L, and peritosol leukocyte count 66/µL with neutrophil 75%. On the fifth hospital day, CRP remained high (6.05 mg/dL) and peritosol leukocyte count was 297/µL with neutrophil 90%. Repeat cultures were all negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Despite numerous antimicrobial agents, diffuse abdominal pain persisted and peritosol leukocyte count remained high (594/µL with neutrophil 57%). On the eleventh hospital day, PD catheter was removed, and he was switched to hemodialysis. Nevertheless, his condition deteriorated. On the twenty-first hospital day, computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen (Fig. 1A) showed diffuse thickening of parietal peritoneum and moderate amount of ascites. On the twenty-third hospital day, oral prednisolone was prescribed at a dose of 40 mg/day (1.0 mg/kg/day) on the diagnosis of fulminant SP. On the next day after corticosteroid therapy, he was getting better with decreased abdominal pain. On the twenty-fifth hospital day, he did not have abdominal pain. CRP decreased significantly from 19.49 mg/dL to 6.75 mg/dL (Fig. 2). On the thirty-ninth hospital day, he was discharged with normalization of CRP (0.22 mg/dL). On June 20, 2012, a follow-up CT scan (Fig. 1B) showed decreased amount of ascites without significant change of peritoneal thickening. In August 2012, he is still free of abdominal pain with a dose of 10 mg/day of oral prednisolone.

Fig. 1.

CT scan of the abdomen. (A) On April 26, 2012, it showed diffuse thickening of parietal peritoneum, mesenteric thickening with vascular engorgement, and moderate amount of ascites. (B) On June 20, 2012, it showed decreased amount of ascites without significant change of peritoneal and mesenteric thickening.

Fig. 2.

Clinical course of the present case of fulminant sclerosing peritonitis successfully treated with corticosteroid therapy.

DISCUSSION

SP is a rare form of peritoneal inflammation which is reported to occur as an idiopathic form or secondary form in association with long-standing PD, prior abdominal surgery, recurrent peritonitis, and beta-blocker (practolol) treatment. The major risk factor for SP is PD treatment. In PD, the continual exposure to nonphysiologic PD solutions and intermittent peritonitis are probable precipitants for the development of SP, with the duration of PD being the most relevant single factor (1, 8). Nonphysiologic PD solutions such as high concentrations of glucose and lactate, low pH, and bioincompatible substances may induce a chronic sterile inflammation in the peritoneal membrane with upregulation of several cytokines resulting in collagen synthesis by mesothelial cells and fibroblasts (2). The underlying process of SP may be immunological. Moreover, they can directly damage the peritoneal membrane, and might contribute to the development of SP.

Peritoneal sclerosis has two distinct forms. Simple peritoneal sclerosis (SS form) is a mild fibrosing condition of the peritoneal membrane that appears in most patients after several years of PD. The SP form is a dramatic progression of the sclerosis after an inflammatory insult, such as peritonitis. The sclerotic tissue is thicker than in SS, and a marked chronic inflammatory infiltrate is present (9). In a small minority, these sclerotic changes are magnified so that the visceral organs are encased in a fibrotic abdominal cocoon. The severe SP like this has been termed sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) or encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) (1). Kawanishi et al. (4) proposed the stage classification and therapeutic options for EPS. Inflammatory stage with manifestations of fever, increased CRP levels, and ascites develop several weeks or months after the removal of a PD catheter. Steroid therapy is recommended during the early stage. If the EPS with ileus symptoms is not relieved or recurs within 1 month, steroid dose reduction and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is recommended at this encapsulating stage. If ileus symptoms remain despite the absence of inflammatory manifestations, laparatomy and enterolysis is considered at this ileus stage.

With the increasing number and survival of PD patients, SP becomes an important problem. Estimated prevalence of SP is reported to be 0.5%-0.9% of PD patients (1, 8, 10, 11). SP usually occurs in patients receiving PD for more than 4-5 yr, and most SP patients have a past medical history of infectious peritonitis. The clinical presentation of SP is variable. The common manifestations are ultrafiltration and clearance failure in PD patients, abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weight loss and malnutrition. These reflect fibrous thickening of the peritoneal membrane, inhibition of peristalsis, encapsulating sclerosis and small bowel obstruction. The uncommon manifestation is acute sterile peritonitis. This reflects an acute peritoneal inflammation of SP. The fulminant form of SP like this is rare, but it can occur as a second phase phenomenon immediately following acute bacterial peritonitis (7). In our case, a fulminant SP may present like or develop immediately following acute culture-negative peritonitis.

Diagnosis of SP is made by clinical and radiological methods such as CT scanning, or by surgical laparotomy with excision of sclerosed peritoneum. Histopathology is now seldom required as CT scanning with the clinical features can make a diagnosis of SP. SP should be considered in any patient on prolonged PD who develops recurrent abdominal pain or bowel obstruction in the absence of active infectious peritonitis. The combined CT imaging features of peritoneal enhancement, calcification, and thickening, bowel wall thickening, loculated fluid collections, and tethered small bowel loops in this clinical setting should be considered diagnostic of SP (1, 12). In our case, SP was diagnosed by the CT findings of peritoneal enhancement and thickening, bowel wall thickening, mesenteric thickening with nodularity, and ascites even after PD catheter removal in the clinical setting of acute sterile peritonitis developed in PD patient.

There is no evidence-based therapy for SP. Treatment of secondary SP in PD patient depends on the severity of symptoms at the time of presentation. It includes cessation of PD, change to hemodialysis, nutritional support, tamoxifen, immunosuppressive therapy (9, 13-15), and surgery. Intestinal enterolysis can be performed if intestinal obstruction symptoms are not improved by steroid administration or TPN (4, 16). Anti-fibrotic agent, such as tamoxifen, may have been used without significant benefit. The benefit with immunosuppressive agents in the previous case reports was variable according to drug chosen, clinical features, and treatment timing. Corticosteroid therapy may be effective for an acute inflammatory state of fulminant SP (3, 4, 7, 13). In our case, acute sterile peritonitis of fulminant SP was dramatically improved immediately after corticosteroid therapy.

Once EPS with ileus symptoms have appeared, mortality is extremely high due to illness related to bowel obstruction or complications of surgery. A major limitation to the success of therapy is the delayed diagnosis. A high index of suspicion is important for early intervention (1). CT scanning should be considered in the patient with the presence of clinical manifestations suspicious for SP.

References

- 1.Kawaguchi Y, Kawanishi H, Mujais S, Topley N, Oreopoulos DG International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis Ad Hoc Committee on Ultrafiltration Management in Peritoneal Dialysis. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: definition, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Perit Dial Int. 2000;20:S43–S55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merkle M, Wörnle M. Sclerosing peritonitis: a rare but fatal complication of peritoneal inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:709673. doi: 10.1155/2012/709673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori Y, Matsuo S, Sutoh H, Toriyama T, Kawahara H, Hotta N. A case of a dialysis patient with sclerosing peritonitis successfully treated with corticosteroid therapy alone. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:275–278. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawanishi H, Harada Y, Noriyuki T, Kawai T, Takahashi S, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Treatment options for encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis based on progressive stage. Adv Perit Dial. 2001;17:200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajani R, Smyth J, Koffman CG, Abbs I, Goldsmith DJ. Differential effect of sirolimus vs prednisolone in the treatment of sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:2278–2280. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.12.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evrenkaya TR, Atasoyu EM, Unver S, Basekim C, Baloglu H, Tulbek MY. Corticosteroid and tamoxifen therapy in sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in a patient on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2423–2424. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtney AE, Doherty CC. Fulminant sclerosing peritonitis immediately following acute bacterial peritonitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:532–534. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigby RJ, Hawley CM. Sclerosing peritonitis: the experience in Australia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:154–159. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int. 1999;19:478–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawanishi H, Kawaguchi Y, Fukui H, Hara S, Imada A, Kubo H, Kin M, Nakamoto M, Ohira S, Shoji T. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan: a prospective, controlled, multicenter study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:729–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim BS, Choi HY, Ryu DR, Yoo TH, Park HC, Kang SW, Choi KH, Ha SK, Han DS, Lee HY. Clinical characteristics of dialysis related sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: multi-center experience in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46:104–111. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafford-Johnson DB, Wilson TE, Francis IR, Swartz R. CT appearance of sclerosing peritonitis in patients on chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:295–299. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199803000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fagugli RM, Selvi A, Quintaliani G, Bianchi M, Buoncristiani U. Immunosuppressive treatment for sclerosing peritonitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:1343–1345. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.5.1343b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junor BJ, McMillan MA. Immunosuppression in sclerosing peritonitis. Adv Perit Dial. 1993;9:187–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhandari S, Wilkinson A, Sellars L. Sclerosing peritonitis: value of immunosuppression prior to surgery. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9:436–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawanishi H, Harada Y, Sakikubo E, Moriishi M, Nagai T, Tsuchiya S. Surgical treatment for sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. Adv Perit Dial. 2000;16:252–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]