Abstract

Fibrocartilaginous dysplasia (FCD) has occasionally led to a misdiagnosis and wrong decision which can significantly alter the outcome of the patients. A 9-yr-old boy presented with pain on his left distal thigh for 6 months without any trauma history. Initial radiographs showed moth eaten both osteolytic and osteosclerotic lesions and biopsy findings showed that the lesion revealed many irregular shaped and sclerotic mature and immature bony trabeculae. Initial diagnostic suggestions were varied from the conventional osteosarcoma to low grade central osteosarcoma or benign intramedullary bone forming lesion, but close observation was done. This study demonstrated a case of unusual fibrocartilaginous intramedullary bone forming tumor mimicking osteosarcoma, so that possible misdiagnosis might be made and unnecessary extensive surgical treatment could be performed. In conclusion, the role of orthopaedic oncologist as a decision maker is very important when the diagnosis is uncertain.

Keywords: Fibrocartilaginous Dysplasia, Osteosarcoma, Orthopaedic Oncologist, Diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Osteosarcoma is the most common malignant tumor of the bone (1). The population affected is predominantly children, teenagers, and young adults aged 10-30 yr (2). In most case, typical radiographic features clearly demonstrate the aggressive bone forming nature of the lesion, with long-bone metaphyseal location, mixed areas of lysis and sclerosis, cortical destruction, various periosteal reactions and abundant extraskeletal soft tissue mass (3, 4).

However, there can be a diagnostic dilemma. Kumar et al. (5) reported a rare form of low grade central osteosarcoma which shares some radiological and histopathological resemblance with fibrous dysplasia (FD). They warned that misdiagnosis of low grade central osteosarcoma as benign lesion may lead inadequate treatment resulting in a more malignant recurrent bone tumor. In the contrary, some cases of aggressive benign bone forming tumors including fibrocartilaginous dysplasia (FCD) or fibrocartilaginous mesenchymoma which resemble with low grade central osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma arising in FD (5-8) has occasionally led to a misdiagnosis and wrong decision which can significantly alter the outcome of the patients.

In this study, we present the radiologic and pathologic features of a fibrocartilaginous intramedullary bone forming tumor of the distal femur mimicking osteosarcoma, so that possible misdiagnosis might be made and unnecessary extensive surgical treatment could be performed.

CASE DESCRIPTION

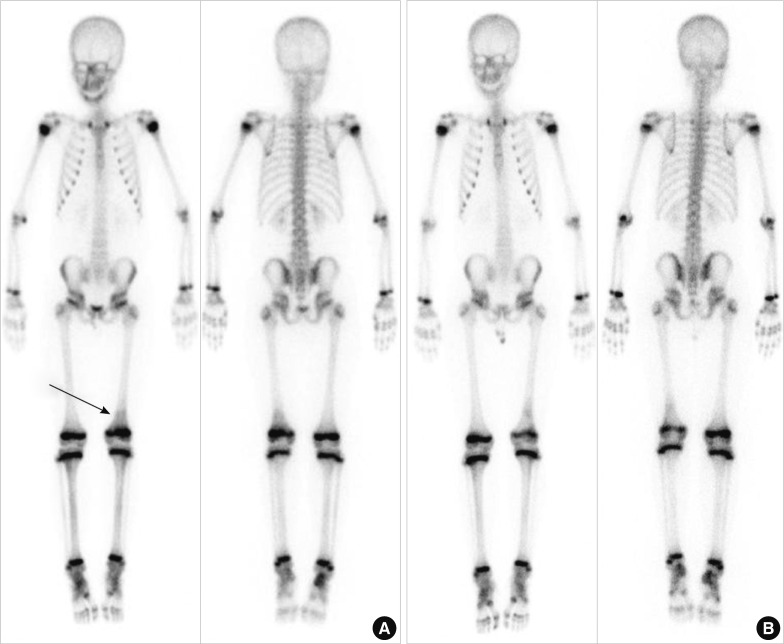

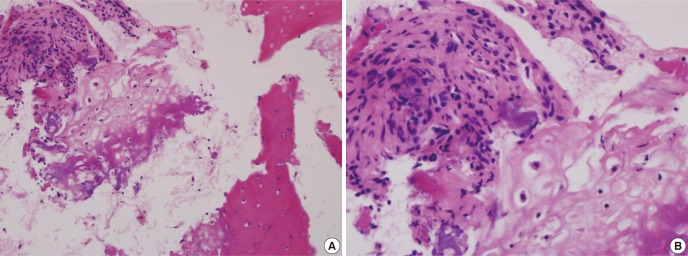

A 9-yr-old boy presented with pain on his left distal thigh for 6 months without any trauma history (date of initial consultation: 2009-12-31). On physical examination, no palpable mass, no tenderness was identified and the range of motion was full. A plain radiograph was taken (Fig. 1A, B) and it showed moth eaten both osteolytic and osteosclerotic lesions in the left distal femoral metaphysis. But there was no periosteal reaction or no cortical destruction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed T1 low and T2 heterogenous signal intensity intramedullary lesion in the metaphysis which had not crossed the growth plate and no definite cortical destruction was also identified (Fig. 1C, D, E, F). A radiologist reported that this case was consistent with an osteosarcoma but the possibility of benign lesion could not be excluded. A whole body bone scan (Fig. 2A) showed mild increased uptake in the left distal femur. Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level and blood chemistry were all within normal limits. An incisional biopsy was performed in the belief of possible malignancy. Pathologic specimen (Fig. 3) showed that the lesion revealed many irregular shaped and sclerotic mature and immature bony trabeculae with moderately cellular stroma composed of relatively uniform spindle cells and cartilaginous components without significant cellular atypia. A "diagnosis" was not easily made because of conflicting debates for the diagnosis were issued from the conventional osteosarcoma to low grade central osteosarcoma or benign intramedullary bone forming lesion after case conference discussion and consultations with foreign pathologic specialists. We informed all of the findings to his parents and decided to have a close observation without any further invasive procedures or surgical treatments, because the boy had a just minimal symptom of intermittent pain and the parents agreed.

Fig. 1.

Initial anterior-posterior and lateral plain radiographs show moth eaten both osteolytic and osteosclerotic lesions in the metaphysis without definite sign of periosteal reaction or cortical destruction. (A) anterior-posterior and (B) lateral radiograph at initial visit. Magnetic resonance imaging showed T1 low and T2 heterogenous signal intensity intramedullary lesion in the metaphysis which had not crossed the growth plate and no definite cortical destruction was also identified. (C) T1-axial cut, (D) T2-axial cut, (E) T1-sagittal cut and (F) T2-coronal cut. AXI, axial; FS, fat suppression; SAG, sagittal; COR, coronal.

Fig. 2.

Initial whole body bone scan showed mild increased uptake in the left distal femur. Whole body bone scan at the time of 36 months after the initial visit shows no definite interval changes of extent and morphology. (A) whole body bone scan at initial presentation and (B) whole body bone scan at 36 months after the initial visit.

Fig. 3.

Inicisional biopsy was done and pathologic specimen showed irregular shaped and scletoric mature and immature bony trabeculae with relatively uniform spindle cells and cartilaginous components without significant cellular atypia. Hematoxylin and eosin stained (A) low- (original magnification, ×400) and (B) high-power (original magnification, ×1,000)

Thirty-six months after initial visit, radiologic findings from the plain radiographs (Fig. 4A, B) and MRI findings (Fig. 4C, D, E, F) showed no significant interval changes of extent and morphology. A whole body bone scan showed mild decreased uptake in comparison to the initial scan (Fig. 2B). Now he is 12-yr-old and clinically he is pain free and has no restriction of any activities until now. There is no sign of growth disturbance. He will be followed annually.

Fig. 4.

Plain radiograph at the time of 36 months after the initial visit shows no definite interval changes of extent and morphology. (A) anterior-posterior and (B) lateral radiograph at the time of 36 months after the initial visit. Magnetic resonance imaging at the time of 36 months after the initial visit shows no definite interval changes of extent and morphology. (C) T1-axial cut, (D) T2-axial cut, (E) T1-sagittal cut and (F) T2-coronal cut. AXI, axial; SAG, sagittal; COR, coronal.

DISCUSSION

Generally, it is widely recognized that a small number of osteosarcoma cases are considerably difficult to interpret radiographically. According to Rosenberg et al. (3), the subtle, rare, and misleading plain film features of some types of bone tumors, such as osteosarcomas simulating osteoblastomas, intracortical osteosarcomas, etc., may produce a confusing radiologic picture. They reported that several factors contributed to the misleading radiolographic patterns of osteosarcomas. These included histological low-grade, lytic, or minimally sclerotic lesions, early detection, and confinement to the intramedullary canal, benign-appearing periosteal reactions, and rare intraosseous locations. On the contrary, some of benign bone tumor can be misdiagnosed as osteosarcoma or malignancy. A case in this study showed radiologic and pathologic findings which might be shown as intramedullary osteosarcoma. Initial plain radiograph showed moth eaten osteolytic and osteosclerotic lesions in distal femur and MRI showed heterogenous signal intensity lesion which can be thought as malignant lesion, so radiologist warned the possibility of osteosarcoma. Also pathologic findings showed many irregular shaped and sclerotic mature and immature bony trabeculae with moderately cellular stroma composed of spindle cells and cartilaginous components, so that pathologist reported similar warning as radiologist. However, the decision was made by the orthopaedic oncologist by the reason of no definite periosteal reaction, no definite cellular atypia, minimally increased uptake in bone scan and mainly due to that massive surgical procedure like wide excision and limb salvage surgery using tumor prosthesis would cause irreversible damage to 9-yr-old patient. Finally the clinical situations over than 36 months of close observation showed that this case could be diagnosed as benign fibrocartilaginous bone forming tumor.

Fibrous dysplasia (FD), a dysplastic process of the bone forming mesenchyme, is histologically characterized by a benign appearing spindle cell fibrous stroma containing scattered, irregularly shaped trabeculae of immature woven bone, lacking osteoblasts, that appear directly from the stroma (9-11). Occasionally, nodules of cartilage can be present in cases of polyostotic or monostotic forms of FD (6, 9, 12, 13). The term "fibrocartilaginous dysplasia" has been applied by some authors for cases that exhibit abundant cartilage (6, 7, 9, 14, 15). Fibrocartilaginous dysplasia is a variant of fibrous dysplasia in which cartilaginous differentiation is identified. FCD occurs in the lower extremities, especially in the proximal lesion of the femur. Radiologically, FCD is similar to conventional FD, the lesion is well demarcated. Cortical expansion can be seen, however, the cortex is always intact. The differential diagnosis of FCD include: enchondroma, chondrosarcoma and well-differentiated intramedullary osteosarcoma and FCD has occasionally led to a misdiagnosis of chondrosarcoma arising in FD or low grade central osteosarcoma (5-8). The distinction between fibrocartilaginous bone forming tumor and other benign and malignant cartilaginous tumors is critical in the management of these patients (9, 10). Our case showed somewhat similar but more aggressive initial radiologic findings than previously reported cases of FCD. Bone scintigraphy (BS) using technetium-99m methylene disphosphate (MDP), had been regarded as sufficiently accurate and adequate for detecting malignant bone tumors. However, one of the drawbacks of the BS is its insensitivity in detecting some cases, which are located intramedullary without cortical bone involvement (16). Our case also showed intramedullary lesion without definite cortical involvement, so that BS showed minimally increased uptake. We can consider that this finding may not be used as a differential point between malignant bone tumor and benign tumor in this case.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a case of unusual aggressive nature of fibrocartilaginous intramedullary bone forming tumor mimicking osteosarcoma, so that possible misdiagnosis might be made and unnecessary extensive surgical treatment could be performed. It is suggested that the role of orthopaedic oncologist as a decision maker is very important in clinical situation, especially when the diagnosis is uncertain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Dr. Scott Nelson for his excellent pathologic comment about this case.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A110416).

References

- 1.Meyers PA, Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44:973–989. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savitskaya YA, Rico-Martínez G, Linares-González LM, Delgado-Cedillo EA, Téllez-Gastelum R, Alfaro-Rodríguez AB, Redón-Tavera A, Ibarra-Ponce de León JC. Serum tumor markers in pediatric osteosarcoma: a summary review. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2:9. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg ZS, Lev S, Schmahmann S, Steiner GC, Beltran J, Present D. Osteosarcoma: subtle, rare, and misleading plain film features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1209–1214. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.5.7572505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campanacci M, Cervellati G. Osteosarcoma: a review of 345 cases. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1975;1:5–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A, Varshney MK, Khan SA, Rastogi S, Safaya R. Low grade central osteosarcoma: a diagnostic dilemma. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:613–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelzmann KS, Nagel DZ, Salyer WR. Case report 114. Skeletal Radiol. 1980;5:116–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00347333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishida T, Dorfman HD. Massive chondroid differentiation in fibrous dysplasia of bone (fibrocartilaginous dysplasia) Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:924–930. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Smet AA, Travers H, Neff JR. Chondrosarcoma occurring in a patient with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. Skeletal Radiol. 1981;7:197–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00361864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reigel DH, Larson SJ, Sances A, Jr, Hoffman NE, Switala KJ. A gastric acid inhibitor of cerebral origin. Surgery. 1971;70:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyriakos M, McDonald DJ, Sundaram M. Fibrous dysplasia with cartilaginous differentiation ("fibrocartilaginous dysplasia"): a review, with an illustrative case followed for 18 years. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:51–62. doi: 10.1007/s00256-003-0718-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bianco P, Riminucci M, Majolagbe A, Kuznetsov SA, Collins MT, Mankani MH, Corsi A, Bone HG, Wientroub S, Spiegel AM, et al. Mutations of the GNAS1 gene, stromal cell dysfunction, and osteomalacic changes in non-McCune-Albright fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:120–128. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanerkin NG, Watt I. Enchondromata with annular calcification in association with fibrous dysplasia. Br J Radiol. 1981;54:1027–1033. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-54-648-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris WH, Dudley HR, Jr, Barry RJ. The natural history of fibrous dysplasia. An orthopaedic, pathological, and roentgenographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44-A:207–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermann G, Klein M, Abdelwahab IF, Kenan S. Fibrocartilaginous dysplasia. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25:509–511. doi: 10.1007/s002560050126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drolshagen LF, Reynolds WA, Marcus NW. Fibrocartilaginous dysplasia of bone. Radiology. 1985;156:32. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.1.4001418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taoka T, Mayr NA, Lee HJ, Yuh WT, Simonson TM, Rezai K, Berbaum KS. Factors influencing visualization of vertebral metastases on MR imaging versus bone scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1525–1530. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]