Abstract

Glycopeptide-based analysis is used to inform researchers about the glycans on one or more proteins. The method's key attractive feature is its ability to link glycosylation information to exact locations (glycosylation sites) on proteins. Numerous applications for glycopeptide analysis are known, and several examples are described herein. The techniques used to characterize glycopeptides are still emerging, and recently, research focused on facilitating aspects of glycopeptide analysis has advanced significantly in the areas of sample preparation, MS fragmentation, and automation of data analysis. These recent developments, described herein, provide the foundation for the growth of glycopeptide analysis as a blossoming field.

Overview of Glycopeptide Analysis Applications

The reasons for analyzing glycopeptides are nearly as diverse as the glycopeptides themselves. In some cases, new and interesting molecules are being discovered and characterized, such as glycosylated snake venom (1). In other cases, comparative glycopeptide analysis is done on endogenous compounds to differentiate between a disease state and a healthy state (2, 3). These types of analyses can be useful both in diagnosing or treating disease and also in developing a better understanding of disease progression and pathology. Furthermore, comparative analyses can be done on endogenous glycoproteins that are isolated from various species (4), with the goal of increasing the understanding of how the same protein, from different species, can have slightly different properties, such as different circulation half-life, or receptor binding affinity, etc.

Glycopeptides originating from recombinantly expressed glycoproteins are also frequent subjects of investigation. These analyses are completed for a variety of reasons. For example, human erythropoietin, an endogenous compound, can be expressed in mammalian cells and is consumed illicitly by athletes in an effort to enhance their performance (5). Because EPO1 is classified as a banned substance, drug testers need to be able to distinguish between recombinant and endogenous forms, and the glycosylation on EPO provides quite a useful means of distinguishing the compounds. In other cases, recombinant proteins are expressed for human and animal consumption for quite legitimate reasons, such as to aid in fertility, as is the case with follicle-stimulating hormone (6). In these instances, characterizing glycosylation of recombinantly expressed proteins is one important step is assessing the overall drug product quality. Finally, glycopeptide analysis can even aid in the development of new products, such as in the development of an HIV vaccine (7–10). Glycopeptide analysis has been used to extensively compare the properties of numerous HIV envelope proteins under investigation for their potential to elicit a strong immune response against the HIV-1 virus. The following section highlights, in more detail, the examples mentioned above. These highlights are by no means an exhaustive list of important problems that are being addressed with glycopeptide analysis. Rather, the examples give the reader a sense of scope of the types of samples that are currently being studied using this technique and the types of problems that can be addressed.

Characterization of Endogenous Glycoproteins

One interesting example of the need for characterization of biologically relevant, isolated glycoproteins is the analysis of several glycopeptides from the venom of Dendroaspis angusticeps (1). These highly active polypeptide compounds were found to be both glycosylated and rich in proline; both features are unusual in snake venom compounds. Because the analytes of interest were generally under 4 kDa, no enzymatic digestion was required prior to analysis; and a top-down approach was used for assigning both the protein sequence, the glycosylation site occupancy, and the glycans themselves (1). The species contained small O-linked glycans. In this research, a variety of MS techniques were used, including MALDI and ESI for ionization and CID and ETD for fragmentation (1). This study represents the first step necessary for understanding the structure/function connection for this particular snake's venom, but it also serves as an illustrative example of the need for classifying glycosylation, as a first step, for achieving a better understanding of a glycoprotein of interest.

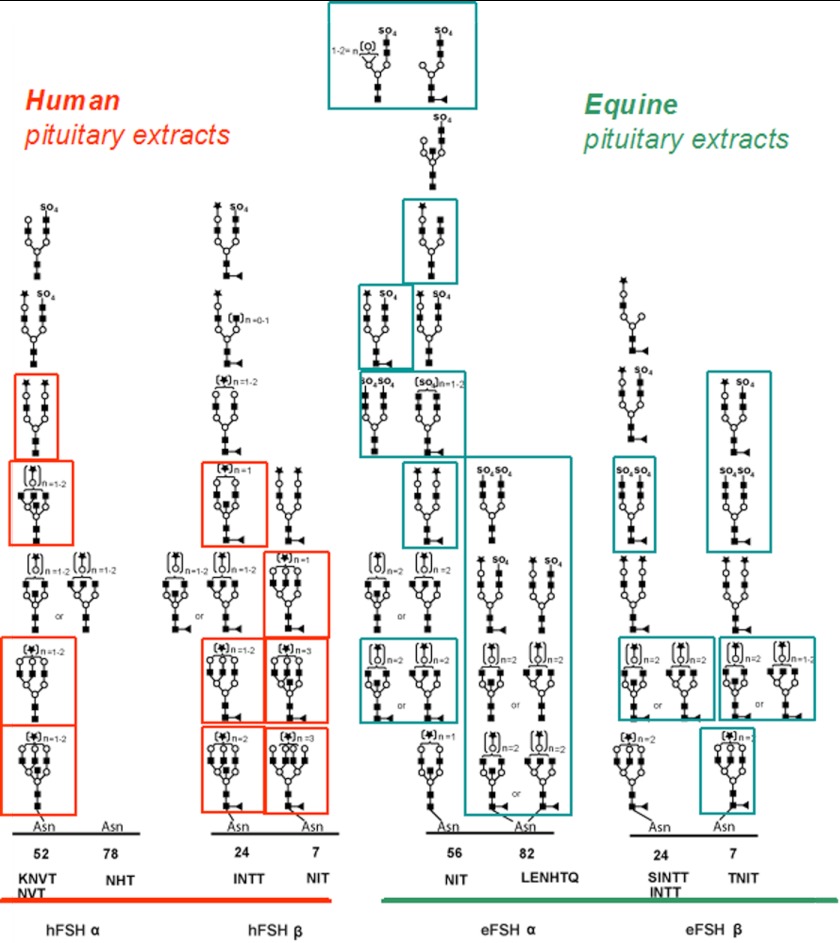

Often, classifying the glycosylation of a protein in one species is a very useful start to understanding that protein's characteristics, but if the protein of interest is present in organisms from multiple species, which is almost always the case, a comparison of the glycosylation on the same protein from different species can provide important insights into the changes in protein properties that are observed in different animals. For example, the glycosylation on the protein's FSH was characterized from human and horse isolates, and between these two species more glycoforms were identified that were unique to one species or the other than those glycoforms that were common to both species (4). The protein, with four different glycosylation sites, was characterized using a proteinase K digestion and analyzed using high resolution ESI-MS and CID data, and ∼30 glycoforms were detected for each species (4). The key data are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the glycopeptides identified from human and equine FSH. Proteins were isolated from pituitary extracts, digested with proteinase K, and characterized by ESI-MS. The glycans are described using the following key: square, HexNAc; circle, hexose; triangle, fucoses; diamond, sialic acid. Structures were inferred based on fragmentation data and biological precedence. Glycoforms in boxes are uniquely identified in one of the two species. Data were adapted from Ref. 4.

Because glycosylation is dependent on the local environment of the cell, this modification can even change when samples are obtained from the same species but from two different biological conditions (2, 3). About 10 years ago, the glycosylation state of haptoglobin was shown to be different between healthy cells and cancer cells (11), and this finding, along with other notable works showing that the glycosylation in certain proteins from individuals with cancer varies, compared with healthy controls (12, 13), opens up the possibility for using the glycosylation state both as a marker for disease state and also as a potential window into understanding the biology of the disease state itself. Although such studies are tantalizing, the analytical techniques to support the work must be in place and capable of processing clinical samples. Both the ability to detect the glycoforms from the protein of interest, from a highly complex sample, and the ability to quantify those resulting glycoforms are current challenges that are being tackled by emerging methods (2, 3).

Characterizing Recombinant Glycoproteins

In addition to the need to characterize endogenous analytes, equally important is the analysis of glycosylation from recombinantly expressed proteins. An interesting example highlighting this need is provided in Ref. 5, where the goal is to understand the glycosylation profile of recombinantly expressed EPO, a banned substance for professional athletes, so that this protein could be detected and differentiated from endogenous EPO. In this case, the recombinant protein was treated with trypsin and Glu-C, and the glycopeptide products were monitored by CE-MS using a TOF detector (5). Both O-linked and N-linked glycopeptides were detected, and the authors found several glycopeptides containing Neu5Gc in the recombinant form of the protein, which is significant because this glycoform is not native to humans and could identify the sample as being recombinantly expressed. This study is a more recent example of the successful glycopeptide analysis of recombinant EPO, which has also been accomplished previously. For examples, see Refs. 14–16.

Although glycopeptide analysis in the drug testing arena is a niche application, this analysis is much more widely practiced for the characterization of legally prescribed therapeutic glycoproteins. One report describes the glycopeptide analysis of recombinant FSH, a glycoprotein used to treat infertility (6). Characterizing the glycosylation on therapeutic glycoproteins is one important way that manufacturers can monitor the batch-to-batch consistency of their manufacturing process, and these analyses can also help to distinguish biosimilars, such as generic forms of therapeutic proteins. To obtain coverage of all four glycosylation sites on FSH, the investigators found that a chymotrypsin digestion was more useful than simply digesting with trypsin (6). Data were acquired on a qTOF mass spectrometer, and both high resolution MS and CID data were used to confirm the glycopeptide compositions (6).

In addition to characterizing the glycosylation of glycoprotein pharmaceuticals that are already on the market or in late stages of development, another important aspect of characterizing recombinant glycoproteins is supporting drug discovery. For the last decade, glycopeptide analysis has served to aid HIV researchers who are interested in developing the recombinant protein gp120 into an effective vaccine for HIV-1 (7–10). Although this protein is extensively glycosylated, with 20–30 N-linked glycosylation sites, depending on the exact sequence of the protein, glycopeptide analysis of this protein has been useful in developing a three-dimensional model of the full protein, including the glycoforms, which consume about half of the protein's mass (7). These analyses have also shown that the glycosylation on different HIV-1 variants changes (8–10). Furthermore, the glycoforms derived from recombinant gp120 proteins known to be on transmitted viruses are different from the glycoforms that are typically found on the recombinantly expressed version of the analogous protein found on the virus from chronically infected patients (10). Researchers have shown that this particular protein's glycosylation is also highly diverse, with over 300 glycoforms typically characterized per recombinantly expressed protein (8–10). These studies were all done using a tryptic digestion and HPLC-MS and MS/MS on high resolution instruments, and in some instances the work was supported with off-line HPLC followed by MALDI-TOF/TOF analyses (7–10).

In summary, the types of applications warranting glycopeptide analysis are quite diverse, and the methods used to solve each problem at hand also vary. Frequently, a digestion strategy must be designed that takes into account the nature of the specific protein to be characterized. In the examples above, no digestion was necessary in one case (1), and in another case, chymotrypsin was shown to be the enzyme of choice (6). Proteinase K was also chosen in one of the cited references (4). In most cases, trypsin was used as the sole enzyme; however, sometimes pairing trypsin with a second enzyme, such as Glu-C in the case of the EPO analysis, provides significant advantages over trypsin alone (5).

Although the analysis of recombinant glycoproteins typically does not require the use of an up front protein purification method, this step is essential when characterizing glycoproteins from endogenous sources. Again, this step is typically dependent upon the exact protein to be isolated, but more research in enhancing the detection of glycopeptides in general, along with glycopeptides from a specific protein of interest, is a developing field that is expanded upon more below.

Another interesting observation can be made in considering the above-described applications. No consensus exists in the field as to the best MS method to characterize glycoproteins. In the examples above, both MALDI and ESI data were used, along with several different types of mass spectrometers, including TOF/TOF, qTOF, oaTOF, ion traps, FT-ICR, and triple quadrupoles. Additionally, both ETD and CID data were employed, and in at least one case, no MS/MS data were used to support the assignments (5).

When a diversity of MS methods is employed, a diversity of data analysis strategies naturally follows. In many of the examples above, no particular strategy for analyzing the data, other than manually matching the candidate mass to the mass of its assigned glycopeptide, was explicitly described. In other cases, CID data were acquired and manually interpreted to support the high resolution assignments. In still other cases, some tools designed to support glycopeptide analysis were cited as being important aids. Clearly, data interpretation aspects of glycopeptide analysis are an important area that must be further developed, if glycopeptide analysis is to become routinely and more widely implemented.

One final important observation should be acknowledged regarding all the glycopeptide analysis applications described above. In each case, the analysis method provides composition information about the glycans but not full structural information, i.e. sequence, branching, linkage, and anomeric assignments. Often, investigators using glycopeptide data obtain some degree of glycan connectivity information, particularly when CID data are employed, but linkage and anomeric information is absent in typical MS/MS data for glycopeptides. It is common practice in the field to depict “best guess” assignments for the glycan structures, such as those shown in Fig. 1, using a combination of the fragmentation data and “biological precedence” or a basic understanding of the types of structures that are typically formed, based on the glycosylation processing enzymes available. If complete structural data for the glycans are required, glycopeptide analysis can be paired with glycan analysis. For more information about obtaining structural information for glycans, readers may explore Refs. 17, 18.

The remaining portion of this review focuses on the emerging work in methods development supporting the field of glycopeptide analysis. Specifically, what sample enrichment and chromatographic methods are emerging? What new tools from the MS community could aid in data acquisition? What is the state of software development for supporting the MS analysis of glycopeptide data?

Emerging Methods Supporting Glycopeptide Analysis

Sample Enrichment and Separation

Sample enrichment of glycoproteins and glycopeptides is a key step prior to acquiring useful data for glycopeptide analysis. Except for recombinantly expressed proteins, where the glycoprotein of interest is already available in high concentration and high purity, affinity enrichment is necessary for a successful analysis. Various methods of affinity enrichment have recently been reviewed elsewhere (19). Briefly, common strategies involve using an antibody that recognizes the protein of interest, when just one glycoprotein is to be profiled (20, 21), or using lectins to select for a group of proteins that are glycosylated (22, 23). One attractive recent example of proteome-wide glycoprotein enrichment involves using a series of lectins to capture proteins with specific types of glycosylation (24). For example, Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA); was used to capture sialylated structures, whereas Aleuria aurantia agglutinin (AAL) was used to capture fucosylated structures (24). This strategy can also be used in conjunction with a Multiple Affinity Removal System (MARS) column to deplete abundant (nonglycosylated) proteins, further enriching the remaining sample in glycoproteins (24).

In contrast to enrichment at the protein level, which is typically only required when the sample is from endogenous sources, enrichment and/or separation of glycosylated species at the glycopeptide level is useful for all types of glycopeptide analyses, including the characterization of recombinant glycoproteins. One useful strategy for enhancing the MS signal of glycopeptides is to first remove any peptides that may co-elute (25–28). This strategy has been utilized by multiple groups, taking advantage of a simple enrichment approach using Sepharose beads, as first demonstrated by Wada et al. (25). More recently, an alternative separation strategy using magnetic beads coated with a hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) stationary phase has also been described (29). Although the HILIC approach appears to be quite advantageous, the beads are not currently commercially available; however, the preparation does not seem to require extensive expertise (29).

In addition to (or instead of) the off-line separation methods listed above, on-line (LC-MS) separation and enrichment are almost always used for glycopeptide analysis. Although HPLC-MS separation of glycopeptides with reverse phase (C18) columns is the most widely adopted pre-MS separation method, HILIC columns are also becoming more commonly used as well. Reverse phase columns typically separate the glycopeptides based on the peptide portion, although most of the glycoforms containing the same peptide sequence co-elute. This co-elution can be an advantage, in terms of data analysis, because all the glycoforms of a given glycopeptide are easier to find in the data set. However, co-elution is also disadvantageous in that abundant glycoforms can suppress the signals of lesser abundant species. HILIC columns provide an alternative separation strategy in that the glycoforms interact with the hydrophilic column; thus, the glycoforms for a given peptide are more readily separated. Advances in the use of HILIC columns for glycopeptide analysis have been reviewed separately (30).

In the separation of glycopeptide isomers, using a graphitized carbon column is another useful strategy that could be employed (31). Lebrilla and co-workers (31) used this stationary phase in a microchip for nanoflow separations followed by MS and MS/MS analysis. This approach was useful for detecting 13 different glycoforms for RNase B, a glycopeptide that typically shows five different compositions. (Others have also shown that PGC columns provide a similar separation performance to reverse phase columns (32).)

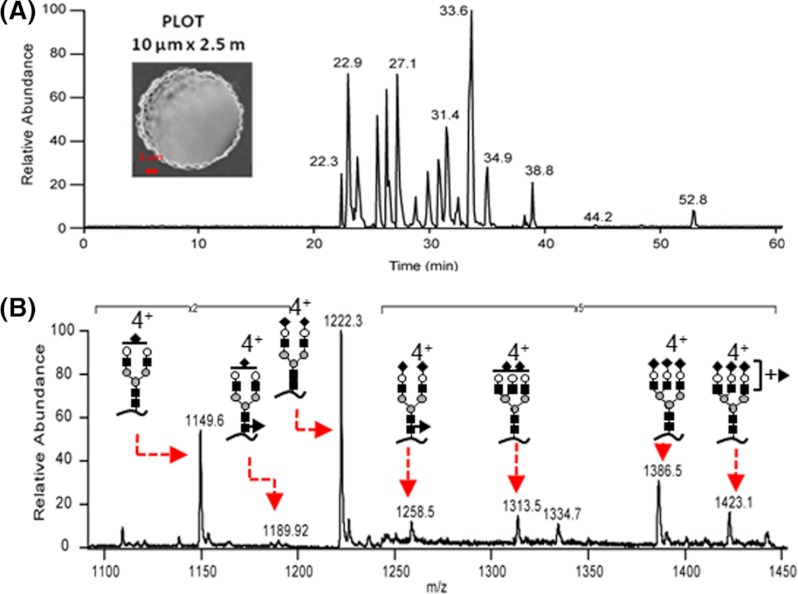

Separation at the nanoscale has significant advantages when sample quantities are limited, such as when endogenous glycoproteins are to be studied. A quite promising and emerging method for these types of separations includes porous layer open tubular (PLOT) columns (2). Recent work has shown extensive glycosylation coverage on a biologically isolated protein from lung cancer, where a total of 13 ng of protein was used for 10 LC-MS runs (2). The implementation of these types of columns will certainly open up the field of glycoproteomics to be able to answer more challenging biological questions when only limited samples are available. Fig. 2 includes data from a PLOT column.

Fig. 2.

Recent developments using porous-layer open tubular columns for separation and analysis of glycopeptides. A, base peak chromatogram of 10 fmol of tryptic digest of haptoglobin using PLOT-LTQ-CID/ETD-MS platform. B, MS data showing seven glycoforms identified in a site-specific manner on one of haptoglobin's glycosylation sites. Glycan structures are depicted using the same conventions as described in Fig. 1. Data were provided by Prof. B. Karger, Northeastern University.

A final option for separating glycopeptides is to utilize ion mobility. In reference 33, high field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry was used to separate glycoforms that had the same peptide sequence but different O-linked glycosylation sites and different glycans at those sites. This example of glycopeptide separation is interesting because the species that could be separated by ion mobility co-eluted under typical (reverse phase) chromatographic conditions. Therefore, this finding suggests that in some cases ion mobility could be used as an orthogonal separation strategy, when liquid phase chromatographic separation is insufficient.

Mass Spectrometric Fragmentation Methods

Although choosing a separation strategy that maximizes the MS detection of glycopeptides is a key step in the success of glycopeptide analysis, detecting the m/z values of the glycoforms is typically not sufficient for high confidence analysis (34). Fragmentation data on the glycoforms should be used to support the assignments. Historically, CID has been the dissociation method of choice for glycopeptides. Yet this approach has its disadvantages in that little to no fragmentation across the peptide is typically observed, and depending on the glycans present, one may (or may not) obtain sufficient fragmentation along the glycan backbone. Therefore, an active area of research in glycopeptide analysis is exploring the utility and complementarity of alternative fragmentation methods.

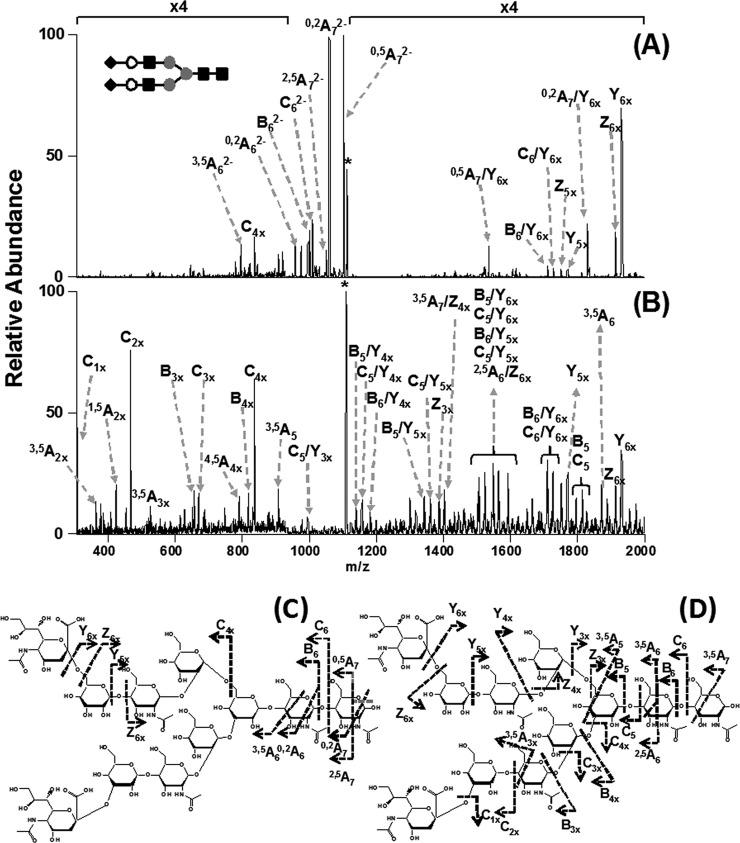

Aside from CID, the second most widely utilized fragmentation for glycopeptide analysis is ETD. For example, the snake venom glycopeptides described above were inferred based in part on their ETD fragmentation data (1); the haptoglobin analysis also relied on ETD (2). This method is useful because extensive peptide backbone cleavage is readily observed, and this fragmentation information is very complementary to the data obtained during CID. Fig. 3 shows an example of a glycopeptide fragmented both by CID and ETD, to further illustrate the differences in the dissociation methods.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of two fragmentation methods for glycopeptides. A, collision-induced dissociation data of an N-linked glycopeptide from RNase B. B, electron transfer dissociation data for the same glycopeptide. Both data sets were acquired on an LTQ-Velos linear ion trap (Thermo Scientific). Glycan structures are depicted using the same conventions as described in Fig. 1. Data were provided by Z. Zhu, University of Kansas.

Whereas the implementation of ETD is not brand new to the field of glycopeptide analysis, particularly for N-linked glycopeptides, recent work by Packer and co-workers (32) has shown that this technique is highly suitable for characterizing the very heavily O-linked protein MUC-1. This protein can frequently possess five O-linked sites in a span of less than 20 amino acids (32), and characterization of the analytes this complex is surely at the very edge of what is possible with today's technology ETD fragmentation was highly useful in discriminating the various O-linked glycoforms on multiple glycosylated peptides.

Another option for obtaining complementary fragmentation information for glycopeptides is exploring CID regimes that input more energy into the ions. Examples of higher energy CID data would include the fragmentation typically observed in a MALDI-postsource decay experiment or in implementing “HCD” on the orbitrap. Both of these dissociation methods are also being utilized (35–38), although their fragmentation is less orthogonal to low energy CID than is ETD. A recent good example of implementing postsource decay data into a glycoproteomics workflow is provided in the analysis of the O-linked glycopeptides on MUC-1 (35). The utility of HCD for glycopeptide analysis was shown by Segu and Mechref (36) and Cordwell and co-workers (37); other groups are still discovering and praising the utility of this approach (38).

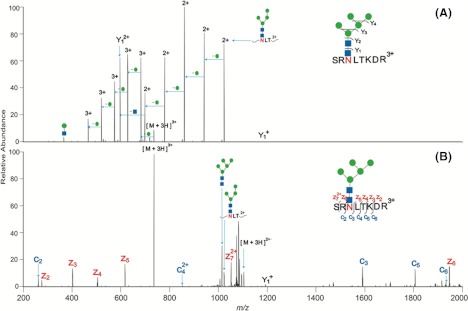

Another possible future dissociation method for glycopeptides may be UV-photodissociation (UVPD) (39). Although not yet applied to glycopeptides, this fragmentation method has shown great promise on glycans in that significantly more fragmentation across the glycan is present than is observed with CID (39). This additional fragmentation can be used to provide detailed structural information about the glycan, including the linkages of the monosaccharides. As mentioned above, obtaining structural information on the glycan portion of glycopeptides is not possible with currently implemented fragmentation methods. To obtain structural information, researchers must pair their glycopeptide analysis experiments with glycan analysis experiments. Even when these two sets of experiments are done simultaneously, a full view of the glycans is not present because glycan analysis loses the information regarding the site(s) of attachment to the protein. The ability to obtain structural information on glycopeptides would represent a significant advance in the field of glycoprotein analysis. Fig. 4 shows a comparison of fragment ions obtained from CID versus UVPD for an N-linked glycan; although not yet applied to glycopeptides, this technique is the field's current best hope for obtaining structural information at the glycopeptide level.

Fig. 4.

MS/MS data of doubly deprotonated [2Ant2SiA-2H]2− by CID (A) and by 193 nm (B) UVPD with 10 pulses and the product ions assigned from CID (C) and UVPD (D). Data were provided by Prof. J. Brodbelt, University of Texas, Austin.

Data Analysis

Although separating and detecting glycopeptides are important, the final hurdle over which glycoproteomics practitioners must ascend is assigning the MS data to glycopeptide compositions in an accurate and expedient fashion. Although analyses for simple glycoproteins, with a limited number of glycosylation sites, can often be done manually by expert researchers, automation of the analysis workflow offers several advantages. Three critical factors are as follows: 1) time savings; 2) higher confidence that the assignments are correct, because software can offer the option to calculate a false discovery rate; and 3) a lower level of expertise is necessary to interpret the results using automation versus manual analysis. Although the benefits of automation are clear, what is less clear is which automation strategy will ultimately become the approach of choice for end users. Currently, several different platforms are under development, each with their unique advantages and quirks.

The publicly available analysis tools that currently appear most promising can be delineated into three categories as follows: 1) those that facilitate the assignment of candidate compositions from (high resolution) MS data; 2) those that score potential assignments against some type of MS/MS data, typically CID; and 3) those that use both MS and MS/MS data for inputs. Generally, both MS and MS/MS data are required to provide a high confidence assignment for any glycopeptide composition (34). Unfortunately, only a few tools are currently available to the public that make use of both types of data in one package.

For obtaining potential candidate compositions, GlycoMod (http://web.expasy.org/glycomod/), is the most highly cited tool (40). It has been in existence for over a decade and has extensive functionality for matching glycopeptide compositions to MS data, including the ability to select multiple enzymes for in silico digestion and providing both “known” glycopeptide compositions along with those that are mathematically possible, even if they have not been observed in nature yet (40). Other publicly available tools designed specifically for matching the masses of glycopeptides to the MS data include GlycoPep DB (http://hexose.chem.ku.edu/glycop.htm) (41) and GlycoSpectrumScan (http://www.glycospectrumscan.org.) (42). These tools have unique advantages in that they both can handle multiply charged MS data, whereas GlycoMod only processes singly charged MS data. Additionally, GlycoPep DB uses a curated database of biologically relevant glycans, which reduces the number of irrelevant potential matches to be considered.

After obtaining candidate compositions from high resolution MS data, researchers use a different set of tools to interpret the MS/MS data. The two most powerful tools that utilize MS/MS data to identify glycopeptide compositions are GlycoMiner (http://www.chemres.hu/ms/glycominer/tutorial.html) (43) and GlycoPep Grader (44) (http://glycopro.chem.ku.edu/GPGHome.php). GlycoMiner was developed based on glycopeptide fragmentation as observed in a qTOF mass spectrometer, and GlycoPep Grader was optimized for MS/MS data from an ion trap. Therefore, the two tools are complementary in that they are aimed at different audiences. Both have been shown to be highly effective in assigning glycopeptides, and GlycoPep Grader is particularly advantageous in that its false discovery rate was shown to be very low.

An alternative to using separate software to interpret the MS and MS/MS data is to use a workflow where both data types are input and used. One highly promising and publicly available tool for glycopeptide analysis that functions in this manner is GlypID (45, 46). GlypID is still in developmental stages, but it is publicly available. One valuable feature of GlypID is that it can make use of CID data and HCD data. It is available on line at: http://mendel.informatics.indiana.edu/∼chuyu/glypID/index.html. Another semi-automated strategy for interpreting both MS and MS/MS data is to input glycan types as variable modifications into an existing proteomics software package, such as Sequest (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). This approach is described in Ref. 47. Although using robust commercial software that accepts both MS and MS/MS data is highly attractive, this approach suffers from the need to input all possible glycoforms as variable modifications. Therefore, this approach becomes impractical if a large number of glycan types are to be searched.

In summary, the field of data analysis software to support glycopeptide assignments is at least a decade behind proteomics software development. Clearly more tools are needed, particularly as new methods of fragmenting glycopeptides become more mainstream. Once robust analysis tools are developed and broadly implemented, data analysis would no longer be the chief bottleneck in glycoproteomics workflows, and a much larger pool of users could engage in these important experiments.

Concluding Remarks

Glycopeptide-based analysis by mass spectrometry is a field in flux, with researchers currently developing critically needed solutions to problems associated with sample preparation, MS analysis, and data interpretation. Continued development of tools in these areas is needed to achieve the following goals: effective separation and ionization of all glycopeptides of interest, even among complex samples; effective fragmentation so that optimal information about the glycan and peptide components can be inferred; and effective software to interpret the data in an automated fashion. Although significant progress has been made in each of these three areas in just the last 2 years, more effort is needed to reduce to common practice many of these emerging methods and tools. Researchers have already shown that glycopeptide analysis can serve diverse and extensive needs, and the number of applications for glycopeptide analysis is expected to expand as the technology to support the work becomes more refined. There is no doubt that glycopeptide analysis will continue to blossom into an essential component of basic biological and biomedical research.

Acknowledgments

The contributions to this article by Barry Karger (Fig. 2), Zhikai Zhu (Fig. 3), and Jenny Brodbelt (Fig. 4) are greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

* This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI094797 and R01GM103547.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- EPO

- erythropoietin

- UVPD

- UV-photodissociation

- HILIC

- hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography

- MALDI

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- CID

- collision-induced dissociation

- ETD

- electronic transfer dissociation

- CE

- capillary electrophoresis

- oaTOF

- orthogonal acceleration time of flight.

REFERENCES

- 1. Quinton L., Gilles N., Smargiasso N., Kiehne A., De Pauw E. (2011) An unusual family of glycosylated peptides isolated from Dendroaspis angusticeps venom and characterized by combination of collision-induced and electron transfer dissociation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 22, 1891–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang D., Hincapie M., Rejtar T., Karger B. L. (2011) Ultrasensitive characterization of site-specific glycosylation of affinity-purified haptoglobin from lung cancer patient plasma using 10-μm i.d. porous layer open tubular liquid chromatography-linear ion trap collision-induced dissociation/electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 83, 2029–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li Y., Tian Y., Rezai T., Prakash A., Lopez M. F., Chan D. W., Zhang H. (2011) Simultaneous analysis of glycosylated and sialylated prostate-specific antigen revealing differential distribution of glycosylated prostate-specific antigen isoforms in prostate cancer tissues. Anal. Chem. 83, 240–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dalpathado D. S., Irungu J., Go E. P., Butnev V. Y., Norton K., Bousfield G. R., Desaire H. (2006) Comparative glycomics of the glycoprotein follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH): glycopeptide analysis of isolates from two mammalian species. Biochemistry 45, 8665–8673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giménez E., Ramos-Hernan R., Benavente F., Barbosa J., Sanz-Nebot V. (2012) Analysis of recombinant human erythropoietin glycopeptides by capillary electrophoresis electrospray-time of flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 709, 81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grass J., Pabst M., Chang M., Wozny M., Altmann F. (2011) Analysis of recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) by mass spectrometric approaches. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 400, 2427–2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu X., Borchers C., Bienstock R. J., Tomer K. B. (2000) Mass spectrometric characterization of the glycosylation pattern of HIV-gp120 expressed in CHO cells. Biochemistry 39, 11194–11204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Go E. P., Irungu J., Zhang Y., Dalpathado D. S., Liao H.-X., Sutherland L. L., Alam S. M., Haynes B. F., Desaire H. (2008) Glycosylation site-specific analysis of HIV envelope proteins (JR-FL and CON-S) reveals major differences in glycosylation site occupancy, glycoform profiles, and antigenic epitopes' accessibility. J. Proteome Res. 7, 1660–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Go E. P., Chang Q., Liao H.-X., Sutherland L. L., Alam S. M., Haynes B. F., Desaire H. (2009) Glycosylation site-specific analysis of clade C HIV-1 envelope proteins. J. Proteome Res. 8, 4231–4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Go E. P., Hewawasam G., Liao H. X., Chen H., Ping L. H., Anderson J. A., Hua D. C., Haynes B. F., Desaire H. (2011) Characterization of glycosylation profile of HIV-1 transmitted/founder envelopes by mass spectrometry. J. Virol. 85, 8270–8284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poon T. C., Mok T. S., Chan A. T., Chan C. M., Leong V., Tsui S. H., Leung T. W., Wong H. T., Ho S. K., Johnson P. J. (2002) Quantification and utility of monosialylated α-fetoprotein in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with nondiagnostic serum total α-fetoprotein. Clin. Chem. 48, 1021–1027 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peracaula R., Tabarés G., Royle L., Harvey D. J., Dwek R. A., Rudd P. M., de Llorens R. (2003) Altered glycosylation pattern allows the distinction between prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from normal and tumor origins. Glycobiology 13, 457–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuzmanov U., Jiang N., Smith C. R., Soosaipillai A., Diamandis E. P. (2009) Differential N-glycosylation of kallikrein 6 derived from ovarian cancer cells or the central nervous system. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 791–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sasaki H., Ochi N., Dell A., Fukuda M. (1988) Site-specific glycosylation analysis of human recombinant erythropoietin. Analysis of glycopeptides or peptides at each glycosylation site by fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 27, 8618–8626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rahbek-Nielsen H., Roepstorff P., Reischl H., Wozny M., Koll H., Haselbeck A. (1997) Glycopeptide profiling of human urinary erythropoietin by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 32, 948–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takegawa Y., Ito H., Keira T., Deguchi K., Nakagawa H., Nishimura S. (2008) Profiling of N- and O-glycopeptides of erythropoietin by capillary zwitterionic type of hydrophilic interaction chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 31, 1585–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zaia J. (2008) Mass spectrometry and the emerging field of glycomics. Chem. Biol. 15, 881–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harvey D. J. (2005) Proteomic analysis of glycosylation: structural determination of N- and O-linked glycans by mass spectrometry. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2, 87–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rebecchi K. R., Desaire H. (2011) Recent mass spectrometric based methods in quantitative N-linked glycoproteomics. Curr. Proteomics 8, 269–277 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wuhrer M., Stam J. C., van de Geijn F. E., Koeleman C. A., Verrips C. T., Dolhain R. J., Hokke C. H., Deelder A. M. (2007) Glycosylation profiling of immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclasses from human serum. Proteomics 7, 4070–4081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Selman M. H., McDonnell L. A., Palmblad M., Ruhaak L. R., Deelder A. M., Wuhrer M. (2010) Immunoglobulin G glycopeptide profiling by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 82, 1073–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qiu R., Regnier F. E. (2005) Comparative glycoproteomics of N-linked complex-type glycoforms containing sialic acid in human serum. Anal. Chem. 77, 7225–7231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee H.-J., Na K., Choi E.-Y., Kim K. S., Kim H., Paik Y.-K. (2010) Simple method for quantitative analysis of N-linked glycoproteins in hepatocellular carcinoma specimens. J. Proteome Res. 9, 308–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Drake P. M., Schilling B., Niles R. K., Braten M., Johansen E., Liu H., Lerch M., Sorensen D. J., Li B., Allen S., Hall S. C., Witkowska H. E., Regnier F. E., Gibson B. W., Fisher S. J. (2011) A lectin affinity workflow targeting glycosite-specific, cancer-related carbohydrate structures in trypsin-digested human plasma. Anal. Biochem. 408, 71–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wada Y., Tajiri M., Yoshida S. (2004) Hydrophilic affinity isolation and MALDI multiple-stage tandem mass spectrometry of glycopeptides for glycoproteomics. Anal. Chem. 76, 6560–6565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin C. Y., Ma Y. C., Pai P. J., Her G. R. (2012) A comparative study of glycoprotein concentration, glycoform profile, and glycosylation site occupancy using isotope labeling and electrospray linear ion trap mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 728, 49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rebecchi K. R., Wenke J. L., Go E. P., Desaire H. (2009) Label-free quantitation: a new glycoproteomics approach. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 20, 1048–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Y., Go E. P., Desaire H. (2008) Maximizing coverage of glycosylation heterogeneity in MALDI-MS analysis of glycoproteins with up to 27 glycosylation sites. Anal. Chem. 80, 3144–3158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yeh C. H., Chen S. H., Li D. T., Lin H. P., Huang H. J., Chang C. I., Shih W. L., Chern C. L., Shi F. K., Hsu J. L. (2012) Magnetic bead-based hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography for glycopeptide enrichments. J. Chromatogr. A 1224, 70–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zauner G., Deelder A. M., Wuhrer M. (2011) Recent advances in hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) for structural glycomics. Electrophoresis 32, 3456–3466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hua S., Nwosu C. C., Strum J. S., Seipert R. R., An H. J., Zivkovic A. M., German J. B., Lebrilla C. B. (2012) Site-specific protein glycosylation analysis with glycan isomer differentiation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 403, 1291–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thaysen-Andersen M., Wilkinson B. L., Payne R. J., Packer N. H. (2011) Site-specific characterisation of densely O-glycosylated mucin-type peptides using electron transfer dissociation ESI-MS/MS. Electrophoresis 32, 3536–3545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Creese A. J., Cooper H. J. (2012) Separation and identification of isomeric glycopeptides by high field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 84, 2597–2601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Desaire H., Hua D. (2009) When can glycopeptides be assigned based solely on high resolution mass data? Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 287, 21–26 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hanisch F. G. (2011) Top-down sequencing of O-glycoproteins by in-source decay matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry for glycosylation site analysis. Anal. Chem. 83, 4829–4837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Segu Z. M., Mechref Y. (2010) Characterizing protein glycosylation sites through higher-energy C-trap dissociation. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24, 1217–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scott N. E., Parker B. L., Connolly A. M., Paulech J., Edwards A. V. G., Crossett B., Falconer L., Kolarich D., Djordjevic S. P., Hojrup P., Packer N. H., Larsen M. R., Cordwell S. J. (2011) Simultaneous glycan-peptide characterization using hydrophilic interaction chromatography and parallel fragmentation by CID, higher energy collisional dissociation, and electron transfer dissociation MS applied to the N-linked glycoproteome of Campylobacter jejuni. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, 10.1074/mcp.M000031-MCP201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hart-Smith G., Raftery M. J. (2012) Detection and characterization of low abundance glycopeptides via higher-energy C-trap dissociation and orbitrap mass analysis. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 23, 124–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ko B. J., Brodbelt J. S. (2011) 193 nm ultraviolet photodissociation of deprotonated sialylated oligosaccharides. Anal. Chem. 83, 8192–8200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cooper C. A., Gasteiger E., Packer N. H. (2001) GlycoMod–A software tool for determining glycosylation compositions from mass spectrometric data. Proteomics 1, 340–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Go E. P., Rebecchi K. R., Dalpathado D. S., Bandu M. L., Zhang Y., Desaire H. (2007) GlycoPep DB: A tool for glycopeptide analysis using a “Smart Search. ” Anal. Chem. 79, 1708–1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deshpande N., Jensen P. H., Packer N. H., Kolarich D. (2010) GlycoSpectrumScan: Fishing glycopeptides from MS spectra of protease digests of human colostrum sIgA. J. Proteome Res. 9, 1063–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ozohanics O., Krenyacz J., Ludányi K., Pollreisz F., Vékey K., Drahos L. (2008) GlycoMiner: A new software tool to elucidate glycopeptide composition. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 22, 3245–3254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Woodin C. L., Hua D., Maxon M., Rebecchi K. R., Go E. P., Desaire H. (2012) GlycoPep Grader: A web-based utility for assigning the composition of N-linked glycopeptides. Anal. Chem. 84, 4821–4829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu Y., Mechref Y., Klouckova I., Novotny M. V., Tang H. (2007) in Systems Biology and Computational Proteomics (Ideker T., Bafna V., eds) Vol. 4532, pp. 96–107 Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mayampurath A. M., Wu Y., Segu Z. M., Mechref Y., Tang H. (2011) Improving confidence in detection and characterization of protein N-glycosylation sites and microheterogeneity. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 25, 2007–2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Singh C., Zampronio C. G., Creese A. J., Cooper H. J. (2012) Higher energy collision dissociation (HCD) product ion-triggered electron transfer dissociation (ETD) mass spectrometry for the analysis of N-linked glycoproteins. J. Proteome Res. 11, 4517–4525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]