Abstract

The nutrient-responsive β-O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification of critical effector proteins modulates signaling and transcriptional pathways contributing to cellular development and survival. An elevation in global protein O-GlcNAc modification occurs during the early stages of osteoblast differentiation and correlates with enhanced transcriptional activity of RUNX2, a key regulator of osteogenesis. To identify other substrates of O-GlcNAc transferase in differentiating MC3T3E1 osteoblasts, O-GlcNAc-modified peptides were enriched by wheat germ agglutinin lectin weak affinity chromatography and identified by tandem mass spectrometry using electron transfer dissociation. This peptide fragmentation approach leaves the labile O-linkage intact permitting direct identification of O-GlcNAc-modified peptides. O-GlcNAc modification was observed on enzymes involved in post-translational regulation, including MAST4 and WNK1 kinases, a ubiquitin-associated protein (UBAP2l), and the histone acetyltransferase CREB-binding protein. CREB-binding protein, a transcriptional co-activator that associates with CREB and RUNX2, is O-GlcNAcylated at Ser-147 and Ser-2360, the latter of which is a known site of phosphorylation. Additionally, O-GlcNAcylation of components of the TGFβ-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) signaling complex, TAB1 and TAB2, occurred in close proximity to known sites of Ser/Thr phosphorylation and a putative nuclear localization sequence within TAB2. These findings demonstrate the presence of O-GlcNAc modification on proteins critical to bone formation, remodeling, and fracture healing and will enable evaluation of this modification on protein function and regulation.

Advances in proteomic approaches are revealing the abundance of β-O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc)1 modification on highly phosphorylated proteins and regulatory enzymes involved in post-translational processing (1, 2). First reported in 1984 in B-lymphocytes (3), O-GlcNAc modification is now appreciated as a nutrient-responsive mechanism for modulating signal transduction (4, 5) and transcriptional regulation (6, 7). In contrast to N- and O-linked glycosylation taking place in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, reversible O-GlcNAcylation occurs in the cytoplasm and nucleus and is catalyzed by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), which transfers GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc to Ser/Thr residues, and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which removes it. These highly conserved enzymes are expressed in all mammalian tissues (8–11).

The OGT gene encodes three splice variants differing in the number of N-terminal tetratricopeptide repeats that mediate protein-protein interactions and subcellular localization (8, 12). The full-length nucleocytoplasmic form of OGT is O-GlcNAc-modified, tyrosine-phosphorylated, and dynamically redistributed within the cell upon insulin stimulation (2, 13–15). Ablation of OGT is embryonically lethal or developmentally limiting in animal models (10, 16, 17) with the noted exception of Caenorhabditis elegans. In C. elegans, the phenotypes of oga-1 and ogt-1 null mutants suggest the enzymes are involved in macronutrient storage and life span (18–20), and subsequent studies revealed the presence of O-GlcNAc modification at over 800 promoters associated with transcriptional programs influencing carbohydrate metabolism, stress responses, and longevity (21).

The presence of OGT in polycomb group repressor complexes further implicates OGT in the regulation of myriad genes involved in tissue differentiation and spatial patterning during embryogenesis (22, 23). In cellular models of differentiation, modulation of OGT and OGA impacts the expression and activity of markers characteristic of tissue specification (24–28). This has been observed in differentiating osteoblasts whereby inhibition of OGA enhanced the expression of osteocalcin, a marker indicative of progression to the later stages of osteoblastogenesis (28). The increased rate of differentiation in osteoblasts was attributed to the potentiation of the transcriptional activity of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), a master regulator of osteogenic programs, by O-GlcNAc modification of RUNX2 (28). Accumulating evidence continues to establish the adult skeleton as a nutrient- and insulin-sensitive tissue that communicates with other organs via bone-specific endocrine signals (e.g. osteocalcin (OCN) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF23)) thereby coupling bone metabolism to whole-body nutrient and mineral homeostasis (29–33). O-GlcNAc modification of the insulin receptor substrates, critical mediators of insulin/IGF-1 signaling, raises the possibility that O-GlcNAc cycling serves as a nutrient-responsive regulatory mechanism in bone tissue (34). It is evident from immunoblot analysis that many proteins are O-GlcNAc-modified in osteoblasts, and the extent of protein O-GlcNAc modification changes during osteoblast differentiation (28). The aim of this study was to identify O-GlcNAc-modified substrates of OGT in differentiating osteoblasts.

Advances in methodology to isolate O-GlcNAcylated peptides and the recent availability of multiple modes of peptide fragmentation during tandem mass spectrometry are revealing the ubiquitous nature of this modification (1, 2, 35, 36). The enrichment of O-GlcNAc-modified peptides from complex mixtures of digested proteins has been achieved by enzymatic labeling of the N-acetylglucosamine with chemically reactive moieties amenable to affinity purification, immunoprecipitation with pan-specific anti-O-GlcNAc antibodies, or by wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) lectin affinity chromatography (1, 2, 36–40). The identification of O-GlcNAcylated peptides by conventional collision-induced dissociation (CID) tandem mass spectrometry can be complicated by the labile nature of the O-linkage, which upon fragmentation results in neutral loss of GlcNAc from the Ser/Thr prior to fragmentation of the peptide backbone (36, 41, 42). This impedes detection of O-GlcNAc-modified peptides by database search algorithms and obscures identification of the sites of modification. Peptide fragmentation by electron transfer dissociation (ETD) provides an alternative approach that leaves the fragile O-linkage intact enabling the direct detection of O-GlcNAc-modified peptides and more confident assignment of the sites of modification (43, 44). With the capability of multiple modes of fragmentation, the generation of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) oxonium ions or the neutral loss of GlcNAc from precursor ions during CID or higher energy collision-induced dissociation (HCD) (36) can trigger the acquisition of an ETD spectrum yielding complementary tandem mass spectra of the peptide. The development of algorithms for searching ETD spectra against protein databases (45), the incorporation of neutral loss information during searches of CID spectra (46), and the association of a score with the assignment of the site of modification (47) are further enabling this field. A recent study employing lectin weak affinity chromatography (LWAC) and CID/ETD permitted the identification of over 1,750 unique sites of O-GlcNAcylation on 2,434 synaptosome peptides (2).

In this study, we employed lectin chromatography to identify O-GlcNAc-modified proteins by ETD MS/MS in MC3T3E1 preosteoblasts cultured for 7 days under osteogenic conditions. Although many of the proteins observed in this study were previously reported to be O-GlcNAc-modified in other cell types, in some cases different sites of O-GlcNAc were elucidated. Of particular interest with respect to osteoblast function were sites of O-GlcNAc modification on the TFGβ-activated kinase 1/MAP3K7-binding protein 1 and 2 (TAB1/TAB2), regulatory subunits associated with the TFGβ-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) signaling node (48). Recent findings demonstrate that TAK1 signaling is essential to osteoblast differentiation and skeletal ossification, and it modulates RUNX2 activation and its association with the CREB-binding protein (CBP) (49). CBP, a histone acetyltransferase and transcriptional co-activator, is critical for osteoblast differentiation and skeletal mineralization. A new site of O-GlcNAc modification was observed in the C-terminal domain of CBP at Ser-2360, a known site of phosphorylation (53, 54). Also observed were sites of O-GlcNAcylation on nucleobindin 2 (precursor to the anorexic hormone, nesfatin-1) (55) and the Ser/Thr kinase WNK1 (56), which have roles in nutrient and electrolyte homeostasis, respectively.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Antibodies and providers were as follows: the pan-specific, monoclonal CTD 110.6 antibody specifically recognizing Ser/Thr β-O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (57) was from ThermoScientific (Rockford, IL); GAPDH (H-12), RUNX2 (M-70), α-tubulin (B-7), and HA peptide (F-7) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA); CBP (D6C5), rabbit IgG (2729), and TAB2 (3744S) antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA); OGT antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich; OGA (MGEA5) antibody was from ProteinTech Group Inc. (Chicago, IL); anti-FLAG epitope tag (3×FLAG) was from Fisher; NUCB2 (nesfatin-1) antibody recognizing nucleobindin 2 residues 1–45 was from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Burlingame, CA). The O-GlcNAcase inhibitor O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucopyranosylidene)amino N-phenyl carbamate (PUGNAc) (58) was from Toronto Research Chemicals (Ontario, Canada), and Thiamet G, a more potent and selective inhibitor of OGA enzyme activity (59), was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI).

Osteoblast Cell Culture

Primary normal human osteoblasts (NHOst) (Lonza Inc., Walkersville, MD) and murine C57BL/6 calvarial MC3T3E1 preosteoblasts (subclone E4) (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in α-minimal essential medium (Cellgro-Mediatech, Manassas, VA) with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were grown to subconfluency (90%) before inducing osteogenesis; NHOst cells were differentiated in the presence of 400 nm hydrocortisone and 7.5 mm β-glycerol phosphate (as optimized by the manufacturer), whereas MC3T3E1 cells were differentiated in the presence of 5 mm β-glycerol phosphate and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid. Cells were incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Osteogenic medium was changed every other day for up to 21 days, during which time cells were harvested for mRNA transcript or protein analysis as described below or, alternatively, stained for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. For ALP staining, the MC3T3E1 monolayer was washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 10 min in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The cells were then washed twice with PBS, twice more with 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 9.4, 100 mm NaCl, 50 mm Mg MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20 before incubating with BM Purple alkaline phosphatase substrate (Roche Applied Science) for 18 h. The reaction was terminated by washing cells three times with deionized water.

Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and the concentration was determined by UV absorbance at 260 nm using a NanoDrop 2000 UV-visible spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific). Messenger RNA (1 μg; 260/280 nm ≥2.00) was reverse-transcribed with iScript cDNA synthesis reagents (Bio-Rad), and the resulting cDNAs were amplified with an iCycler iQ real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) in the presence of IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and oligonucleotide primers. Sequence-specific primers were as follows: OCN, forward 5′-GACAAAGCCTTCATGTCCAAG-3′ and reverse 5′-AAAGCCGAGCTGCCAGAGTTT-3′; OGT forward 5′-GACGCAACCAAACTTTGCAGT-3′ and reverse 5′-TCAAGGGTGACAGCCTTTTCA-3′; OGA forward 5′-TATGCTATTTCGCCAGGACTAGA-3′ and reverse 5′-GACCTGCACCCAAACTGAGA-3′ and GAPDH forward 5′-CAGCAAGGACACTGAGCAAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GGTCTGGGATGGAAATTGTG-3′. Resulting amplification products were quantified with iCycler iQ version 3.1 system software (Bio-Rad).

Preparation of Proteins for Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 15 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40 amended with complete-mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich), phosphatase inhibitors sodium fluoride (10 mm), sodium orthovanadate (0.5 mm), sodium pyrophosphate (1 mm), and the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase inhibitor PUGNAc (50 μm). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min. Alternatively, crude nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared from cells using NE-PER extraction reagents (ThermoScientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. GAPDH, RUNX2, and/or HisH1 served as endogenous, cytosolic, or nuclear fraction markers, respectively. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (ThermoScientific) for both total cell lysates and subcellular fractions.

For immunoblot analysis, proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with protein- or modification-specific antibodies for 18 h at 4°C. Membranes were incubated with 1:20,000 secondary dye-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IRDye 680RD or goat anti-mouse 800CW IgG antibodies (Li-Cor; Lincoln, NE). Immunoblots employing the CTD 110.6 O-GlcNAc primary antibody were incubated with the secondary Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse 680 IgM antibody (Invitrogen). Proteins were visualized with an Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor).

LWAC Enrichment of O-GlcNAc-modified Peptides

MC3T3E1 cells were cultured for 7 days under osteogenic conditions and harvested in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 300 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 amended with protease, phosphatase, and O-GlcNAcase inhibitors as described above. Protein was precipitated in acetone, resolubilized in 6 m guanidine hydrochloride, and diluted with 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate. Cysteines were reduced in 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride at 55°C for 1 h and alkylated in 10 mm iodoacetamide at ambient temperature in the dark for 30 min. Protein was digested at a 1:100 concentration with sequencing-grade, modified trypsin (Promega, Madison WI) at 37°C for 40 h. Resulting peptides were centrifuged to remove any remaining insoluble material, acidified with formic acid, and desalted using tC18 Sep-Pak cartridges (Waters). Dried tryptic peptides were solubilized in 0.2 ml of column buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 7.8, 300 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2·2H2O, 1 mm MgCl2·6H2O) and loaded onto a column containing agarose-coupled WGA, prepared as described previously (38, 39). A maximum of 2 mg of peptides was loaded onto the column. The flow rate was 100 μl/min, and eluting fractions were collected and screened for the presence of O-GlcNAc-modified peptides by LC-MS/MS and dot-blot immunoassay with the CTD110.6 O-GlcNAc antibody (supplemental Fig. 2). Positive fractions were combined, desalted, and dried under vacuum.

Separation and MS/MS Analysis of O-GlcNAc-modified Peptides

Peptides from combined fractions from a single LWAC enrichment were separated by C18 reversed phase nano-LC on a 75-μm × 20-cm capillary column packed in-house (YMC ODS-AQ 120Å S5; Waters) with a gradient of 5–60% B over 120 min (mobile phase A: 2% acetonitrile, 0.2% formic acid; mobile phase B: acetonitrile, 0.2% formic acid) at 200 nl/min using an Ultimate 3000 nanoflow system equipped with Chromeleon 6.8 software (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA). To increase the yield, O-GlcNAc-positive fractions from three and then seven sequential LWAC enrichments were combined and separated by two-dimensional LC. The first dimension consisted of a step gradient of 0, 10, 20, 40, 50, 60 75, and 100 mm ammonium acetate (mobile phase A: 2% acetonitrile, 0.2% formic acid; mobile phase B: 500 mm ammonium acetate, pH 2.8) on a 0.5 × 50-mm BioBasic SCX KAPPA column (Fisher). Peptides eluted in each salt step were desalted in-line with an Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 μ-precolumn (0.3 × 5 mm, 5 μm, 100 Å; Dionex) and separated in the second dimension by C18 reversed phase nano-LC as described above.

Peptides were fragmented by alternating CID/ETD MS/MS or by ETD MS/MS only on the five most abundant ions in the full mass spectrum survey scan (m/z range, 400–2000) with an LTQ XL ion-trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher). The parameters used for ETD were as follows: 100 ms activation time; emission current, 130 μA; automatic gain control, 30,000; temperature, 170°C; supplemental activation was turned off; isolation width, 4 Da; reagent ion, fluoranthene. Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat count of two, a repeat duration of 30 s, and exclusion duration of 180 s. In subsequent studies, an aliquot of the seven-enrichment pooled fraction was analyzed using an Orbitrap Elite (ThermoFisher). Peptides were separated by two-dimensional LC as described above, and full mass spectrum survey scans (m/z 400–2000) were acquired at a resolution of 60,000. The top 10 most abundant ions in each survey scan were fragmented by HCD using a collision energy of 35, and the product ions were detected in the Orbitrap. The presence of HexNAc oxonium ions (m/z 138.06, 186.08, and 204.1) within the top 30 product ions triggered the acquisition of an ETD fragmentation spectrum of the precursor ions in the Velos ion trap.

Data Analysis

Xcalibur RAW files were converted to peak list files in -mzXML format using ReAdW-3.5.1. CID/ETD data were searched separately using the Batch Tag Web feature of Protein Prospector 2 version 5.7.3 against the SwissProt database 2011.01.11 (Mus musculus, 16,338 entries). ETD spectra were searched with allowances for variable HexNAc modifications (+203.2 Da) on Ser/Thr (O-linkage) and Asn (N-linkage) residues, as well as oxidation on Met residues with an upper limit of four modifications per peptide. Carbamidomethylated cysteine was included as a static modification. CID data were searched using the same parameters allowing the neutral loss of HexNAc from the precursor and fragment ions. Trypsin was selected as the proteolytic enzyme with a maximum of two missed cleavages allowed. Precursor ion and fragment ion mass tolerances were set at 1 and 1.5 Da, respectively. Data obtained on the Orbitrap were converted to -mzXML format using a converter obtained from ProteoWIZARD (version 3.0.4171). HCD and ETD data were searched against the SwissProt database 2012.03.21 (M. musculus, 16,520 entries) using Prospector version 5.10.8 with 50 ppm precursor tolerance and 0.5-Da fragment tolerance. The minimum peptide score was 15, and the maximum peptide expectation value was 0.05. Tandem mass spectra corresponding to putative O-GlcNAc-modified peptides were manually confirmed by comparing experimental sequence ions to theoretical fragment ions generated by Protein Prospector. CID and HCD spectra of putative O-GlcNAc-modified peptides were examined for the presence of the expected neutral loss of HexNAc from the precursor ion and/or the generation of HexNAc oxonium ions.

Transient TAB2 or CBP Expression

For immunological characterization of TAB2 and CBP O-GlcNAc modification, HEK293 cells were transfected with human CMV promoter-driven N-terminal 3×FLAG-tagged TFGβ-activated kinase 1/MAP3K7-binding protein 2 (TAB2) (GeneCopoeia Inc., Rockville, MD) or mouse RSV promoter-driven C-terminal HA-tagged CBP (Invitrogen) in the presence of PolyFect transfection reagent (Qiagen). After 48 h, cells were washed twice and then cultured for 18 h in modified improved essential medium (Invitrogen) with 1% FBS, 1% penicillin, streptomycin/amphotericin B (HyClone, Logan, UT) in the absence or presence of PUGNAc (50–100 μm) or Thiamet G (20 μm).

Total cell lysates or nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared as described above. TAB2 was immunoprecipitated from 250 to 500 μg of total protein with 3×FLAG antibody-conjugated agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C. CBP was immunoprecipitated from 0.5 to 1 mg of total protein in the presence of protein A-agarose beads (EMD Chemicals, Inc., San Diego) at 4°C. Mock immunoprecipitations were performed with normal rabbit IgG (0.5 μg/mg) antibody to control for nonspecific interactions. Beads were collected by centrifugation and washed extensively with 150–300 mm NaCl in 15 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.4. Immunoprecipitates were eluted with an equal bead volume of 2× XT gel loading sample buffer (Bio-Rad) with 10% β-mercaptoethanol at 100°C for 5 min. Gel-purified and trypsin-digested CBP was also analyzed by LC-MS/MS using HCD-triggered ETD on the Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer as described above.

RESULTS

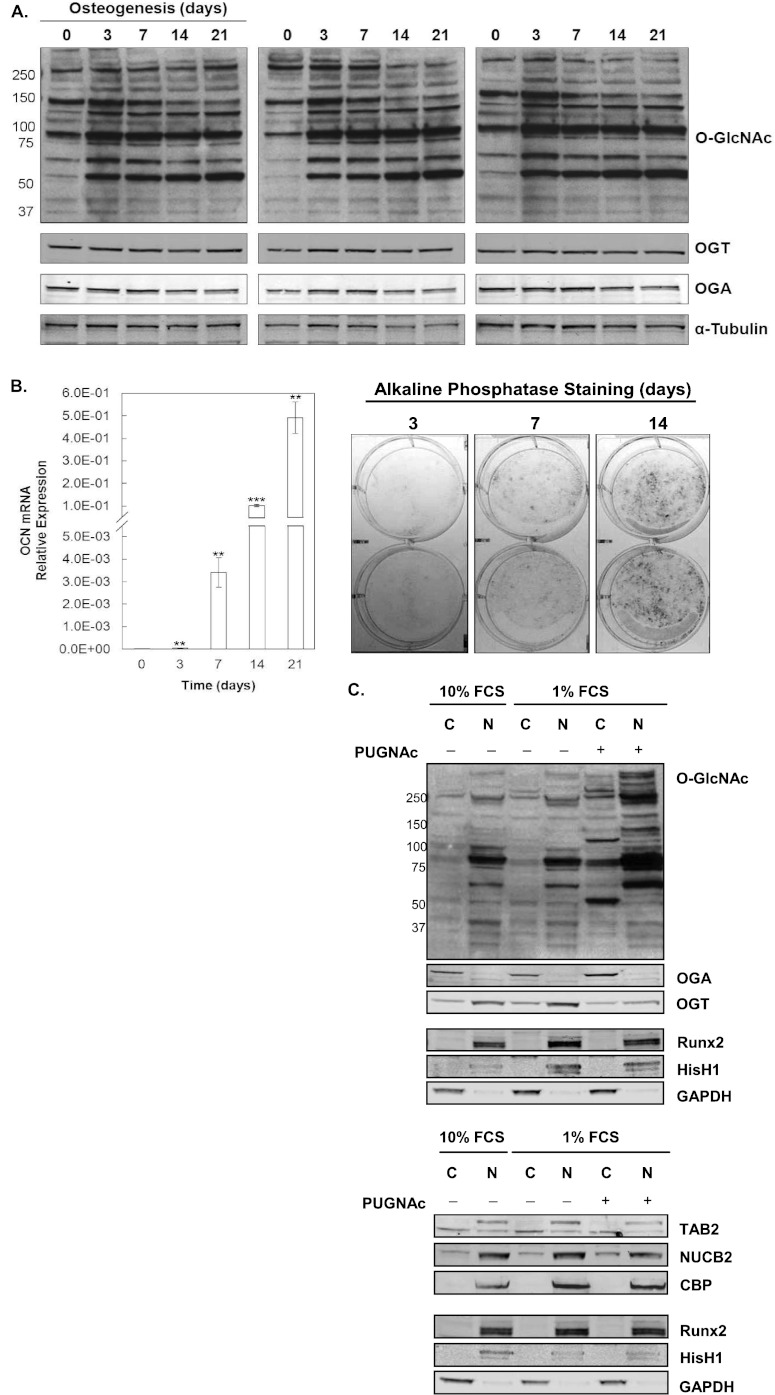

The MC3T3E1 (subclone E4) cells can be differentiated into osteoblasts in the presence of ascorbic acid and β-glycerol phosphate, resulting in increased expression of osteoblast-specific markers ALP and OCN, secretion of collagen matrix, and the formation of mineral nodules (60–62). In this study, MC3T3E1 cells were cultured under osteogenic conditions for 0, 3, 7, 14, and 21 days, and the progression of osteoblast differentiation was confirmed by measuring OCN transcript expression and ALP activity (Fig. 1). The pattern of protein O-GlcNAc modification was assessed by immunoblot analysis using a pan-specific CTD 110.6 anti-O-GlcNAc antibody. Consistent with previous observations (28), the pattern and intensity of protein O-GlcNAcylation varied during the progression of osteogenesis with the highest overall levels of modification occurring between days 3 and 7 (Fig. 1A). To test whether this also occurs in primary osteoblasts, NHOst were differentiated, and the protein was probed for O-GlcNAc modification by immunoblot analysis. Similar to murine MC3T3E1 cells, a burst of elevated protein O-GlcNAcylation occurred during the first few days of differentiation in NHOst cells (supplemental Fig. 1). Changes in the extent of protein O-GlcNAc modification occurring concomitantly with increased expression OGT and OGA have been observed during the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells toward myoblasts or chondrocytes (26, 27). During the time course of differentiation in MC3T3E1 cells the expression of OGT and OGA did not change (Fig. 1A). As this was the first analysis of OGT and OGA protein expression in osteoblasts, we also confirmed that OGT was localized preferentially in the nuclear compartment, and OGA was primarily localized in the cytosol (Fig. 1C). Inhibition of OGA with PUGNAc resulted in increased O-GlcNAc modification of nuclear and cytosolic proteins, and as observed previously in vivo, the expression of OGA increased in response to inhibition (63).

Fig. 1.

Changes in global protein O-GlcNAc modification during differentiation of MC3T3E1 osteoblasts. MC3T3E1 cells were differentiated for up to 21 days under osteogenic conditions. A, Protein lysates (30 μg) were probed for protein O-GlcNAc modification and OGT, OGA, and α-tubulin as a loading control. Three biological replicates are shown. B, Elevated expression of osteoblast markers was confirmed by quantitative PCR analysis of OCN transcript (left panel) and staining for ALP activity (right panel). OCN transcript levels were normalized against GAPDH (mean ± S.E., n = 3). Significant differences between day 0 and any given time point were determined by Student's unpaired t test: p < 0.01 < (**), or p < 0.001 (***). C, Immunoblot analysis of cytosolic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions prepared from cells differentiated in the presence of osteogenic factors (5 mm β-glycerol phosphate, 50 μg/ml ascorbate) for 3 days with 10% FCS or 1% FCS in the absence or presence of the OGA inhibitor PUGNAc. GAPDH, histone H1 (HisH1), and RUNX2 served as controls for subcellular fractionation and loading.

To identify O-GlcNAc-modified substrates of OGT in differentiating osteoblasts, WGA LWAC was employed to enrich O-GlcNAc-modified peptides from MC3T3E1 cells cultured under osteogenic conditions for 7 days. Harvested protein was digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were separated by lectin chromatography on a 3-m WGA-conjugated agarose column, as described previously (38). Fractions were collected and screened for the presence of O-GlcNAc-modified peptides by dot-blot immunoassay with the CTD 110.6 antibody (supplemental Fig. 2) and by LC-MS/MS. Peptides containing N- or O-linked HexNAc monosaccharides were minimally retained on the column and eluted at the end of the main peak after the bulk of unmodified peptides. These fractions were combined and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry using multiple complementary fragmentation approaches as follows: 1) alternating CID/ETD fragmentation; 2) ETD alone; 3) and on the Orbitrap, the acquisition of ETD spectra was triggered upon detection of HexNAc-derived oxonium ions following HCD. Of the putative O-GlcNAc-modified peptides detected, 23 could be confidently confirmed by manual inspection of the spectra (supplemental material). Nine novel sites of modification were assigned (Table I). Although the lectin chromatography enrichment approach was relatively simple, the majority of peptides identified in this study were unmodified. Recent improvements in the lectin chromatography approach are now yielding much more efficient enrichment of O-GlcNAc-modified peptides, including one of the largest O-GlcNAc-modified proteome datasets achieved to date (2).

Table I. Tandem mass spectrometric identification of O-linked HexNAc-modified peptides isolated from differentiating osteoblasts.

Novel sites of modification are in boldface, and ambiguous sites of modification are underlined. An asterisk indicates a site of HexNAc modification either at or proximal to a known site of phosphorylation (± four amino acids) (see supplemental Table 2).

| Accession | Protein | Gene symbol | Peptide | Site | MS/MS | z | m/z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P45481 | CREB-binding protein | CBP | 135QAASTSGPTPPAS(HexNAc)QALNPQAQK156 | Ser-147 | CID | 2 | 1177.59 |

| 2344SPAPVQSPRPQSQPPHS(HexNAc)SPSPR2365 | Ser-2360* | ETD | 4 | 632.51 | |||

| Q8BT14 | CCR4-NOT transcription complex subunit 4 | CNOT4 | 309SNPVIPIS(HexNAc)SSNHSAR323 | Ser-316 | ETD | 3 | 591.11 |

| Q61191 | Host cell factor 1 | HCF1 | 612TAAAQVGTSVSSAANTSTRPIITVHK637 | 620–623* | ETD | 4 | 745.12 |

| 1232QPETYHT(HexNAc)YTTNTPTTTR1248 | Thr-1238 | ETD | 3 | 739.96 | |||

| 1232QPETYHTYTT(HexNAc)NTPTTTR1248 | Thr-1241* | ETD | 3 | 739.95 | |||

| P48678 | Prelamin A/C | LMNA | 600AAGGAGAQVGGSISSGSSASSVTVTR625 | 613–624 | CID | 2 | 1213.58 |

| Q8BFW7 | Lipoma-preferred homolog | LPP | 179SATKPQPAPQAAPIPVTPIGTLKPQPQPVPAS (HexNAc)YT TASTSSRPTFNVQVK227 | Ser-210 | ETD | 5 | 1053.02 |

| Q811L6 | Microtubule- associated serine/threonine-protein kinase 4 | MAST4 | 2172SATATTTAIATTTTTTSAGHSDCSSHK2198 | 2176–2177 | ETD | 4 | 719.17 |

| Q02780 | Nuclear factor 1 A-type | NFI-A | 352SGFSSPSPSQTSSLGTAFTQHHRPVITGPR381 | 362–363* | ETD | 5 | 667.41 |

| Q6PIJ4 | Nuclear factor related to κB-binding protein | NFRκB | 1258IQTVPASHLQQGT(HexNAc)ASGSSK1276 | Thr-1270 | ETD | 3 | 701.34 |

| Q02819 | Nucleobindin 1 | NUCB1 | 399KQQLQEQS(HexNAc)APPSKPDGQLQFR419 | Ser-406 | ETD | 4 | 655.05 |

| P81117 | Nucleobindin 2 | NUCB2 | 400KLQQGIAPS(HexNAc)GPAGELK415 | Ser-408 | ETD | 3 | 599.92 |

| Q80U93 | Nuclear pore complex protein | NUP214 | 489SSASVTGEPPLYPTGS(HexNAc)DSSR508 | Ser-504* | CID | 2 | 1100.67 |

| Q6ZPK0 | PHD finger protein 21A | PHF21A | 278FTPTTLPTS(HexNAc)QNSIHPVR294 | Ser-286 | ETD | 3 | 701.00 |

| Q9DBG5 | Perilipin 3 | PLN3 | 69TLTTAAVSTAQPILSK84 | 76–77 | CID | 2 | 903.71 |

| Q6NXI6 | Regulation of nuclear pre-mRNA domain containing protein 2 | RPRD2 | 408EKPVEKPAVS(HexNAc)T(HexNAc)GVPTK423 | Ser-417, Thr-418 | ETD | 3 | 692.22 |

| Q02614 | SAP30-binding protein | S30BP | 229KGTTT(HexNAc)NATATSTSTASTAVADAQK252 | Thr-233 | ETD | 3 | 829.74 |

| Q689Z5 | Protein strawberry notch homolog 1 | SBNO1 | 106TPPAT(HexNAc)T(HexNAc)NRQTITLTK120 | Thr-110, Thr-111 | ETD | 3 | 684.62 |

| Q8CF89 | TGF-β-activated kinase 1/MAP3K7- binding protein 1 | TAB1 | 385VYPVSVPYSSAQSTSK400 | 393–399 | CID | 2 | 953.05 |

| Q99K90 | TGF-β-activated kinase 1/MAP3K7-binding protein 2 | TAB2 | 453VVVT(HexNAc)QPNTKYTFK465 | Thr-456 | ETD | 3 | 576.97 |

| Q80X50 | Ubiquitin-associated protein 2-like | UBAP2l | 621RYPSS(HexNAc)ISSSPQKDLTQAK638 | Ser-625* | ETD | 3 | 733.73 |

| P83741 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase WNK1 | WNK1 | 1834DGTEGHVTATS(HexNAc)SGAGVVK1851 | 1,844 | ETD | 3 | 625.97 |

The specificity of OGT for target proteins is thought to be mediated by associated regulatory proteins (2, 64–66). Although efforts to define a consensus motif for O-GlcNAc modification indicate a 10–25-fold enrichment of O-GlcNAcylated sites within a P-X-T(GlcNAc)-X-A and P-V-S(GlcNAc) sequence, respectively (1, 38), a strict consensus motif has not been identified. Examination of OGT substrates with three-dimensionally resolved structures reveals that modification occurs within flexible, solvent-accessible regions that may also be highly phosphorylated (2). Consistent with these findings, sites of O-GlcNAc modification identified in osteoblasts occurred in the vicinity of proline and valine residues, within stretches of multiple serines and threonines, and in close proximity to sites of phosphorylation (supplemental Table 2). In addition to the potential for cross-talk among modifications at specific residues, OGT may impact signaling through the modification of regulatory enzymes (1, 2, 67). O-GlcNAc modification was observed on CBP lysine acetyltransferase, MAST4 and WNK1 kinases, and UBAP2L, a protein involved in ubiquitin conjugation. We also observed O-GlcNAc modification of proteins involved in systemic nutrient homeostasis, including perilipin, a protein involved in lipid droplet formation, and NUCB2, the precursor to the anorexic hormone nesfatin-1. Many of the proteins identified in our screen are involved in transcriptional regulation or have been observed in the nucleus within other cell types. These include TAB2 (68), HCF1 (69), SBNO1 (70), NFRκB (71), CNOT4 (72), NUCB2 (73), PHF21A (74), NF1A (75), Nup214 (76), LPP (77, 78), and CBP (79). The nuclear localization of TAB2, CBP, and NUCB2, was confirmed in differentiated MC3T3E1 cells (Fig. 1D). With regard to osteoblastogenesis, TAK-1 and CBP are critical for skeletal development, and thus we focused further efforts on the TAK1-associated regulatory subunit TAB2 and CBP.

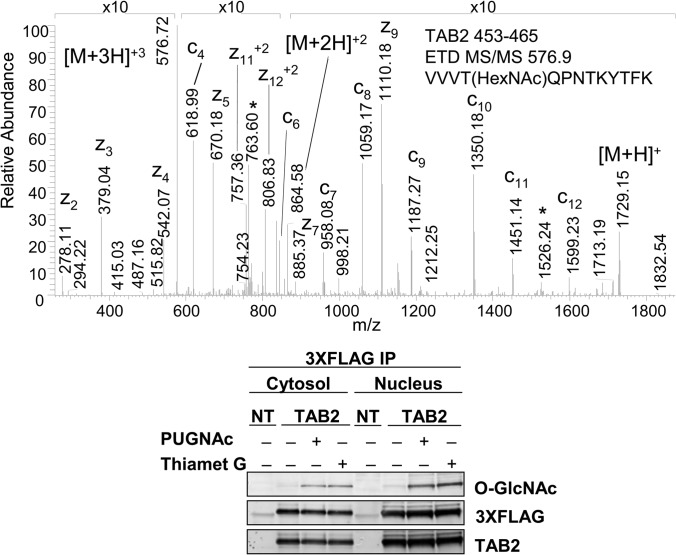

O-GlcNAc modification of TAB2 was observed at Thr-456. The CID MS/MS spectrum of the HexNAc-modified peptide, residues 453–465, of TAB2 exhibited the characteristic neutral loss of the N-acetylglucosamine moiety from the doubly (m/z 762.96) and triply (m/z 509.13) charged precursor ions and the presence of HexNAc oxonium ions at m/z 204.01, 168.08, and 186.07 (supplemental material). Dissociation of the peptide by ETD permitted localization of the site of O-GlcNAc modification at Thr-456 (Fig. 2). This peptide was observed previously in HeLa cells using an enzymatic labeling approach; however, the site could not be assigned (48). Thr-456 is proximal to several sites of phosphorylation at residues Ser-419, Ser-423, Ser-447, Thr-449, and Ser-450. In addition to modulating TAK1 signaling in the cytoplasm, TAB2 functions as a transcriptional co-repressor in association with HDAC3 and NCoR (68). Phosphorylation at Ser-419 and Ser-423, which lie within a nuclear export sequence, regulates trafficking of TAB2 from the nucleus. To determine whether O-GlcNAc modification impacted the subcellular localization of TAB2, the protein was transiently expressed in HEK293 cells grown in the presence or absence of OGA inhibitors and immunoprecipitated from nuclear and cytosolic fractions. Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that treatment with PUGNAc or Thiamet G increased the extent of TAB2 O-GlcNAcylation in the nucleus and cytoplasm; however, the subcellular localization was not significantly altered (Fig. 2). Immunoblotting with the CTD 110.6 O-GlcNAc antibody further validated the observed 203.2 Da mass shift on TAB2 as GlcNAc rather than GalNAc.

Fig. 2.

O-GlcNAc modification of TGF-β-activated kinase 1/MAP3K7-binding protein 2 (TAB2), in differentiating MC3T3E1 osteoblasts. The ETD tandem mass spectrum of TAB2, residues 453–465, confirms a 203.2-Da mass shift at residue Thr-456 (top panel). The peaks labeled with asterisks correspond to unfragmented precursor ions that have undergone a neutral loss of m/z 203.2. Immunoblot analyses of TAB2 immunoprecipitated from nontransfected (NT) or 3×FLAG-TAB2-transfected HEK293 cells cultured in the presence of PUGNAc (50 μm) or Thiamet G (20 μm) further confirm the 203.2-Da mass shift is due to O-GlcNAc modification and reveal the presence of O-GlcNAc-modified TAB2 in both the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments.

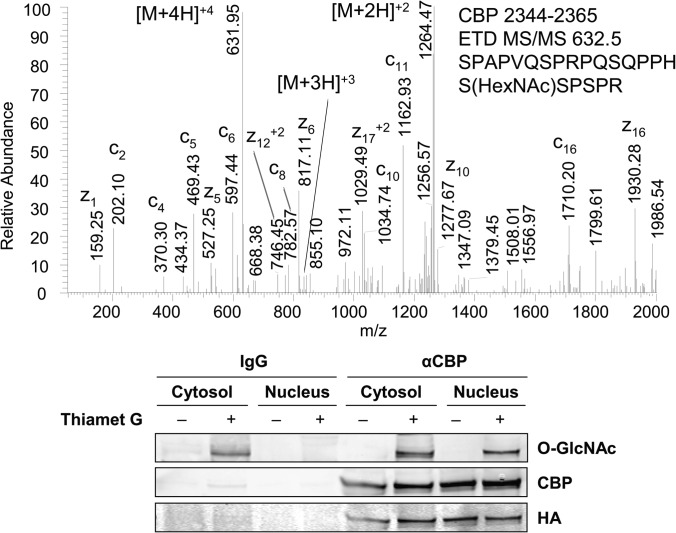

Novel sites of HexNAc modification were observed within the N and C termini of CBP, a highly modified lysine acetyltransferase that is auto-acetylated, phosphorylated, methylated, and sumoylated (53). ETD MS/MS analysis permitted the unambiguous identification of O-GlcNAc modification at Ser-2360, a known site of phosphorylation (Fig. 3) (54). O-GlcNAc modification of CBP was also observed at Ser-147 by CID MS/MS (supplemental material). Although this O-GlcNAcylated peptide, residues 135–156, was observed in brain and synaptosomal preparations, the exact site of modification had not been assigned (1, 2, 13). O-GlcNAc modification at Ser-147 was further confirmed in HEK293 cells by ETD MS/MS (supplemental Fig. 3). The extent of O-GlcNAc modification of CBP increased in the nuclear fractions upon inhibition of OGA, and the localization of protein did not appear to change with enhanced O-GlcNAc modification.

Fig. 3.

O-GlcNAc modification of CBP in differentiating MC3T3E1 osteoblasts. The ETD tandem mass spectrum of HexNAc-modified CBP, residues 2344–2365, indicates O-GlcNAc modification at Ser-2360. Immunoblot analysis of CBP immunoprecipitated from cytosolic and nuclear fractions of HEK293 treated with Thiamet G (20 μm) indicates the presence of O-GlcNAc modification of CBP localized in the nucleus. Immunoprecipitation with IgG was performed as a control for nonspecific binding.

As noted previously, the WGA lectin chromatography approach yields N-linked HexNAc-modified peptides as well as O-linked HexNAc (39). N-Linked HexNAc modification was observed on sulfated glycoprotein 1 (80) and osteonectin/SPARC, one of the most abundant secreted glycoproteins within the bone extracellular matrix (supplemental Table 1) (81).

DISCUSSION

Multiple O-GlcNAc-modified proteins were identified in MC3T3E1 lysates by MS/MS, expanding upon the results of Kim et al. (28), which demonstrated an elevation in protein O-GlcNAc modification during osteoblast differentiation. Although findings from that study suggested that global O-GlcNAc levels were indiscriminately enhanced in MC3T3E1 across a 7-day time period, our expansion of this assay to 21 days revealed more dynamic patterns of O-GlcNAc modification with the progression of osteogenesis. This suggests that O-GlcNAc modulation of specific signaling components may be altered during different phases of osteoblast differentiation.

Accumulating evidence supports a role for OGT and OGA in the modulation of master transcriptional regulators involved in the differentiation of various lineages derived from mesenchymal stromal cells, such as adipocytes, myoblasts, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts. In adipocytes, elevated O-GlcNAcylation of adipogenic CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ decreased the DNA binding and transcriptional activity, respectively, and hindered terminal adipocyte differentiation (24, 25). In C2C12 myoblasts, chronic inhibition of OGA selectively reduced expression of myogenic markers myogenin and MRF4 and blocked myotube formation (26). In ATDC5 chondrocytes, pharmacological inhibition of OGA increased the progression of chondrogenesis (59) and enhanced the expression and activity of matrix metalloprotease (MMP) 2 and 9 (27). In osteoblasts, Kim et al. (28) proposed the increased rate of PTH- and forskolin-stimulated osteoblast differentiation, which occurred with inhibition of OGA, resulted from enhanced transcriptional activity of RUNX2. In this study, we identified O-GlcNAc modification of multiple proteins potentially involved in regulating CREB- and RUNX2-mediated transcription, including CBP, TAB1, and TAB2.

O-GlcNAc modification events have been described on all major components of the TAK1-signaling node, including TAB1 (1, 2, 82), TAB2 (48), TAB3 (1, 2), and TAK1 (1); however, the functional impact of O-GlcNAc modification on TAK1-mediated signaling in osteoblasts has not been addressed. Signal transduction through the TAK1 complex is stimulated by IL-1β, TGFβ, and BMPs. In osteoblasts, signaling through TAK1 modulates transcription by enhancing the association of RUNX2 and CBP, thereby influencing osteoblast differentiation, mineralization, and skeletal development (49). In this study, we observed O-GlcNAc modification of TAB1 and TAB2 and demonstrated for the first time that TAB2 is localized in the nucleus of differentiating osteoblasts.

Two sites of O-GlcNAc modification were assigned on the transcriptional co-activator CBP a 300 kDa acetyltransferase which participates in CREB coactivation. Heterozygous mutations in CBP and its paralog, p300, are associated with Rubenstein-Taybi syndrome, a clinical conditions characterized by mental retardation, microcephaly, and craniofacial abnormalities. Mice which are haploinsufficient for CBP exhibit defects in craniofacial skeletal development and mineralization (51). In osteoblasts, CBP is thought to interact and regulate the transcriptional activity of RUNX2 and CREB and contribute to CREB-mediated expression of BMP2 (51). The activity and protein interactions of CBP are known to be regulated by post-translational modifications. For example, the phosphorylation of CBP at Ser-89 blocks the binding of CBP to transcription factors such as CREB (79). In addition to CBP, CREB and CRTC2 (79) are also O-GlcNAcylated, and OGT has been shown to co-localize with CREB (83) at unique promoter regions in mouse neurons (84). Although the O-GlcNAc modification of an epigenetic regulator such as CBP is consistent with a mechanism proposed for OGT-mediated transcriptional control in a broad sense, it also implicates O-GlcNAc modification in the regulation of the anabolic effects elicited by PTH (50), insulin/IGF-1 (51), BMPs (49, 52), and Wnts (52) in osteoblasts.

Finally, the role of protein glycosylation in osteoblast function is intriguing in the context of a new paradigm that suggests that bone metabolism can directly influence whole-body glucose homeostasis (29, 30, 32, 85, 86). It has been shown that biologically active (i.e. under-carboxylated) and circulating OCN enhances glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in mice by stimulating the production of insulin and adiponectin from pancreatic β-cells and adipocytes, respectively (29–31). Furthermore, the expression of OCN in osteoblasts is dependent upon insulin signaling, suggesting that bone and energy metabolism can reinforce one another in the absence of other negative regulatory factors. Being intimately connected to glucose flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, it has been proposed that the reversible O-GlcNAc modification is poised to respond to shifts in glucose and/or nutrient status (87). As reported for other cell types, we observe an increase in global protein O-GlcNAc modification in osteoblasts cultured in 25 mm versus 5 mm glucose (data not shown). As such, O-GlcNAcylation may represent a contributing mechanism for the control of bone anabolism at the level of the osteoblast. Studies are currently underway to explore the regulation of OGT and OGA as it relates to osteoblast survival and differentiation in the context of bone formation, fracture healing, and alveolar bone loss in diabetic patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Proteomics Center and Mass Spectrometry Facility, a University Research Resource at Medical University of South Carolina, and we thank Jennifer Rutherford Bethard for maintaining instrumentation. We also thank Robert Chalkley (University of California San Francisco) for help with the LWAC protocol and using Protein Prospector. We thank Matt Rice for technical help.

Footnotes

* This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DE020925 (to L.E.B.), and T32 DE017551 05 (to A.K.N.) from the NIDCR and Grants S10 D010731 (to L.E.B.), DK 055524-11A2S1 (to M.S.), and P20 GM103542 (to S.C.W.) from NCRR.

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- O-GlcNAc

- O-linked N-acetylglucosamine

- LWAC

- lectin weak affinity chromatography

- ETD

- electron transfer dissociation

- CBP

- CREB-binding protein

- RUNX2

- runt-related transcription factor 2

- OGT

- O-GlcNAc transferase

- OGA

- O-GlcNAcase

- WGA

- wheat germ agglutinin

- ALP

- alkaline phosphatase

- OCN

- osteocalcin

- PTH

- parathyroid hormone

- IGF-1

- insulin-like growth factor 1

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein

- HCD

- higher energy collision-induced dissociation

- PUGNAc

- O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucopyranosylidene)amino N-phenyl carbamate

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- NHOst

- normal human osteoblast.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alfaro J. F., Gong C. X., Monroe M. E., Aldrich J. T., Clauss T. R., Purvine S. O., Wang Z., Camp D. G., 2nd, Shabanowitz J., Stanley P., Hart G. W., Hunt D. F., Yang F., Smith R. D. (2012) Tandem mass spectrometry identifies many mouse brain O-GlcNAcylated proteins, including EGF domain-specific O-GlcNAc transferase targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7280–7285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trinidad J. C., Barkan D. T., Gulledge B. F., Thalhammer A., Sali A., Schoepfer R., Burlingame A. L. (2012) Global identification and characterization of both O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation at the murine synapse. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 215–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Torres C. R., Hart G. W. (1984) Topography and polypeptide distribution of terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues on the surfaces of intact lymphocytes. Evidence for O-linked GlcNAc. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 3308–3317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wells L., Vosseller K., Hart G. W. (2001) Glycosylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins: signal transduction and O-GlcNAc. Science 291, 2376–2378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hart G. W., Slawson C., Ramirez-Correa G., Lagerlof O. (2011) Cross-talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 825–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Love D. C., Krause M. W., Hanover J. A. (2010) O-GlcNAc cycling: emerging roles in development and epigenetics. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 646–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ozcan S., Andrali S. S., Cantrell J. E. (2010) Modulation of transcription factor function by O-GlcNAc modification. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 353–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lubas W. A., Frank D. W., Krause M., Hanover J. A. (1997) O-Linked GlcNAc transferase is a conserved nucleocytoplasmic protein containing tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9316–9324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heckel D., Comtesse N., Brass N., Blin N., Zang K. D., Meese E. (1998) Novel immunogenic antigen homologous to hyaluronidase in meningioma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 1859–1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shafi R., Iyer S. P., Ellies L. G., O'Donnell N., Marek K. W., Chui D., Hart G. W., Marth J. D. (2000) The O-GlcNAc transferase gene resides on the X chromosome and is essential for embryonic stem cell viability and mouse ontogeny. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5735–5739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Comtesse N., Maldener E., Meese E. (2001) Identification of a nuclear variant of MGEA5, a cytoplasmic hyaluronidase and a β-N-acetylglucosaminidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 283, 634–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kreppel L. K., Blomberg M. A., Hart G. W. (1997) Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9308–9315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tai H. C., Khidekel N., Ficarro S. B., Peters E. C., Hsieh-Wilson L. C. (2004) Parallel identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins from cell lysates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 10500–10501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olsen J. V., Vermeulen M., Santamaria A., Kumar C., Miller M. L., Jensen L. J., Gnad F., Cox J., Jensen T. S., Nigg E. A., Brunak S., Mann M. (2010) Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals widespread full phosphorylation site occupancy during mitosis. Sci. Signal. 3, ra3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang X., Ongusaha P. P., Miles P. D., Havstad J. C., Zhang F., So W. V., Kudlow J. E., Michell R. H., Olefsky J. M., Field S. J., Evans R. M. (2008) Phosphoinositide signalling links O-GlcNAc transferase to insulin resistance. Nature 451, 964–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Donnell N., Zachara N. E., Hart G. W., Marth J. D. (2004) Ogt-dependent X-chromosome-linked protein glycosylation is a requisite modification in somatic cell function and embryo viability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1680–1690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Webster D. M., Teo C. F., Sun Y., Wloga D., Gay S., Klonowski K. D., Wells L., Dougan S. T. (2009) O-GlcNAc modifications regulate cell survival and epiboly during zebrafish development. BMC Dev. Biol. 9, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanover J. A., Forsythe M. E., Hennessey P. T., Brodigan T. M., Love D. C., Ashwell G., Krause M. (2005) A Caenorhabditis elegans model of insulin resistance: altered macronutrient storage and dauer formation in an OGT-1 knockout. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 11266–11271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Forsythe M. E., Love D. C., Lazarus B. D., Kim E. J., Prinz W. A., Ashwell G., Krause M. W., Hanover J. A. (2006) Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog of a diabetes susceptibility locus: oga-1 (O-GlcNAcase) knockout impacts O-GlcNAc cycling, metabolism, and dauer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11952–11957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rahman M. M., Stuchlick O., El-Karim E. G., Stuart R., Kipreos E. T., Wells L. (2010) Intracellular protein glycosylation modulates insulin mediated life span in C. elegans. Aging 2, 678–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Love D. C., Ghosh S., Mondoux M. A., Fukushige T., Wang P., Wilson M. A., Iser W. B., Wolkow C. A., Krause M. W., Hanover J. A. (2010) Dynamic O-GlcNAc cycling at promoters of Caenorhabditis elegans genes regulating longevity, stress, and immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7413–7418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gambetta M. C., Oktaba K., Müller J. (2009) Essential role of the glycosyltransferase sxc/Ogt in polycomb repression. Science 325, 93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sinclair D. A., Syrzycka M., Macauley M. S., Rastgardani T., Komljenovic I., Vocadlo D. J., Brock H. W., Honda B. M. (2009) Drosophila O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) is encoded by the Polycomb group (PcG) gene, super sex combs (sxc). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 13427–13432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li X., Molina H., Huang H., Zhang Y. Y., Liu M., Qian S. W., Slawson C., Dias W. B., Pandey A., Hart G. W., Lane M. D., Tang Q. Q. (2009) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine modification on CCAAT enhancer-binding protein β: role during adipocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19248–19254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ji S., Park S. Y., Roth J., Kim H. S., Cho J. W. (2012) O-GlcNAc modification of PPARγ reduces its transcriptional activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417, 1158–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ogawa M., Mizofuchi H., Kobayashi Y., Tsuzuki G., Yamamoto M., Wada S., Kamemura K. (2012) Terminal differentiation program of skeletal myogenesis is negatively regulated by O-GlcNAc glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andrés-Bergós J., Tardio L., Larranaga-Vera A., Gómez R., Herrero-Beaumont G., Largo R. (2012) The increase in O-linked N-acetylglucosamine protein modification stimulates chondrogenic differentiation both in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33615–33628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim S. H., Kim Y. H., Song M., An S. H., Byun H. Y., Heo K., Lim S., Oh Y. S., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G. (2007) O-GlcNAc modification modulates the expression of osteocalcin via OSE2 and Runx2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 362, 325–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee N. K., Sowa H., Hinoi E., Ferron M., Ahn J. D., Confavreux C., Dacquin R., Mee P. J., McKee M. D., Jung D. Y., Zhang Z., Kim J. K., Mauvais-Jarvis F., Ducy P., Karsenty G. (2007) Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell 130, 456–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferron M., Wei J., Yoshizawa T., Del Fattore A., DePinho R. A., Teti A., Ducy P., Karsenty G. (2010) Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell 142, 296–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fulzele K., Riddle R. C., DiGirolamo D. J., Cao X., Wan C., Chen D., Faugere M. C., Aja S., Hussain M. A., Brüning J. C., Clemens T. L. (2010) Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition. Cell 142, 309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yoshikawa Y., Kode A., Xu L., Mosialou I., Silva B. C., Ferron M., Clemens T. L., Economides A. N., Kousteni S. (2011) Genetic evidence points to an osteocalcin-independent influence of osteoblasts on energy metabolism. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 2012–2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fukumoto S., Martin T. J. (2009) Bone as an endocrine organ. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20, 230–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Klein A. L., Berkaw M. N., Buse M. G., Ball L. E. (2009) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of insulin receptor substrate-1 occurs in close proximity to multiple SH2 domain binding motifs. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 2733–2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang Z., Udeshi N. D., O'Malley M., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Hart G. W. (2010) Enrichment and site mapping of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine by a combination of chemical/enzymatic tagging, photochemical cleavage, and electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 153–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao P., Viner R., Teo C. F., Boons G. J., Horn D., Wells L. (2011) Combining high-energy C-trap dissociation and electron transfer dissociation for protein O-GlcNAc modification site assignment. J. Proteome Res. 10, 4088–4104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vosseller K., Wells L., Hart G. W. (2001) Nucleocytoplasmic O-glycosylation: O-GlcNAc and functional proteomics. Biochimie 83, 575–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vosseller K., Trinidad J. C., Chalkley R. J., Specht C. G., Thalhammer A., Lynn A. J., Snedecor J. O., Guan S., Medzihradszky K. F., Maltby D. A., Schoepfer R., Burlingame A. L. (2006) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine proteomics of postsynaptic density preparations using lectin weak affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 923–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chalkley R. J., Thalhammer A., Schoepfer R., Burlingame A. L. (2009) Identification of protein O-GlcNAcylation sites using electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry on native peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8894–8899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Myers S. A., Panning B., Burlingame A. L. (2011) Polycomb repressive complex 2 is necessary for the normal site-specific O-GlcNAc distribution in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9490–9495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chalkley R. J., Burlingame A. L. (2001) Identification of GlcNAcylation sites of peptides and α-crystallin using Q-TOF mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 12, 1106–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jebanathirajah J., Steen H., Roepstorff P. (2003) Using optimized collision energies and high resolution, high accuracy fragment ion selection to improve glycopeptide detection by precursor ion scanning. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 14, 777–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Syka J. E., Coon J. J., Schroeder M. J., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F. (2004) Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9528–9533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mikesh L. M., Ueberheide B., Chi A., Coon J. J., Syka J. E., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F. (2006) The utility of ETD mass spectrometry in proteomic analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1764, 1811–1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baker P. R., Medzihradszky K. F., Chalkley R. J. (2010) Improving software performance for peptide electron transfer dissociation data analysis by implementation of charge state- and sequence-dependent scoring. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1795–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Darula Z., Chalkley R. J., Baker P., Burlingame A. L., Medzihradszky K. F. (2010) Mass spectrometric analysis, automated identification and complete annotation of O-linked glycopeptides. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 16, 421–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chalkley R. J., Clauser K. R. (2012) Modification site localization scoring: strategies and performance. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 3–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Parker B. L., Gupta P., Cordwell S. J., Larsen M. R., Palmisano G. (2011) Purification and identification of O-GlcNAc-modified peptides using phosphate-based alkyne CLICK chemistry in combination with titanium dioxide chromatography and mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1449–1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Greenblatt M. B., Shim J. H., Zou W., Sitara D., Schweitzer M., Hu D., Lotinun S., Sano Y., Baron R., Park J. M., Arthur S., Xie M., Schneider M. D., Zhai B., Gygi S., Davis R., Glimcher L. H. (2010) The p38 MAPK pathway is essential for skeletogenesis and bone homeostasis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 2457–2473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tyson D. R., Swarthout J. T., Partridge N. C. (1999) Increased osteoblastic c-fos expression by parathyroid hormone requires protein kinase A phosphorylation of the cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate response element-binding protein at serine 133. Endocrinology 140, 1255–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shim J. H., Greenblatt M. B., Singh A., Brady N., Hu D., Drapp R., Ogawa W., Kasuga M., Noda T., Yang S. H., Lee S. K., Rebel V. I., Glimcher L. H. (2012) Administration of BMP2/7 in utero partially reverses Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome-like skeletal defects induced by Pdk1 or Cbp mutations in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 91–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rodríguez-Carballo E., Ulsamer A., Susperregui A. R., Manzanares-Céspedes C., Sánchez-García E., Bartrons R., Rosa J. L., Ventura F. (2011) Conserved regulatory motifs in osteogenic gene promoters integrate cooperative effects of canonical Wnt and BMP pathways. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 718–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hornbeck P. V., Kornhauser J. M., Tkachev S., Zhang B., Skrzypek E., Murray B., Latham V., Sullivan M. (2012) PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D261–D270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huttlin E. L., Jedrychowski M. P., Elias J. E., Goswami T., Rad R., Beausoleil S. A., Villén J., Haas W., Sowa M. E., Gygi S. P. (2010) A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell 143, 1174–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gonzalez R., Mohan H., Unniappan S. (2012) Nucleobindins: bioactive precursor proteins encoding putative endocrine factors? Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 176, 341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. McCormick J. A., Ellison D. H. (2011) The WNKs: atypical protein kinases with pleiotropic actions. Physiol. Rev. 91, 177–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Comer F. I., Vosseller K., Wells L., Accavitti M. A., Hart G. W. (2001) Characterization of a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. Anal. Biochem. 293, 169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Haltiwanger R. S., Grove K., Philipsberg G. A. (1998) Modulation of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine levels on nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins in vivo using the peptide O-GlcNAc-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase inhibitor O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucopyranosylidene)amino-N-phenylcarbamate. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3611–3617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yuzwa S. A., Macauley M. S., Heinonen J. E., Shan X., Dennis R. J., He Y., Whitworth G. E., Stubbs K. A., McEachern E. J., Davies G. J., Vocadlo D. J. (2008) A potent mechanism-inspired O-GlcNAcase inhibitor that blocks phosphorylation of tau in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Franceschi R. T., Iyer B. S. (1992) Relationship between collagen synthesis and expression of the osteoblast phenotype in MC3T3-E1 cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 7, 235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Quarles L. D., Yohay D. A., Lever L. W., Caton R., Wenstrup R. J. (1992) Distinct proliferative and differentiated stages of murine MC3T3-E1 cells in culture: an in vitro model of osteoblast development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 7, 683–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Franceschi R. T., Iyer B. S., Cui Y. (1994) Effects of ascorbic acid on collagen matrix formation and osteoblast differentiation in murine MC3T3-E1 cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 9, 843–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Macauley M. S., Bubb A. K., Martinez-Fleites C., Davies G. J., Vocadlo D. J. (2008) Elevation of global O-GlcNAc levels in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by selective inhibition of O-GlcNAcase does not induce insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34687–34695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cheung W. D., Sakabe K., Housley M. P., Dias W. B., Hart G. W. (2008) O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase substrate specificity is regulated by myosin phosphatase targeting and other interacting proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33935–33941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Iyer S. P., Akimoto Y., Hart G. W. (2003) Identification and cloning of a novel family of coiled-coil domain proteins that interact with O-GlcNAc transferase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5399–5409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Iyer S. P., Hart G. W. (2003) Roles of the tetratricopeptide repeat domain in O-GlcNAc transferase targeting and protein substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24608–24616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dias W. B., Cheung W. D., Hart G. W. (2012) O-GlcNAcylation of kinases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 422, 224–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Baek S. H., Ohgi K. A., Rose D. W., Koo E. H., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. (2002) Exchange of N-CoR corepressor and Tip60 coactivator complexes links gene expression by NF-κB and β-amyloid precursor protein. Cell 110, 55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kristie T. M., Liang Y., Vogel J. L. (2010) Control of α-herpesvirus IE gene expression by HCF-1 coupled chromatin modification activities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 257–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Majumdar A., Nagaraj R., Banerjee U. (1997) Strawberry notch encodes a conserved nuclear protein that functions downstream of Notch and regulates gene expression along the developing wing margin of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 11, 1341–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yao T., Song L., Jin J., Cai Y., Takahashi H., Swanson S. K., Washburn M. P., Florens L., Conaway R. C., Cohen R. E., Conaway J. W. (2008) Distinct modes of regulation of the Uch37 deubiquitinating enzyme in the proteasome and in the Ino80 chromatin-remodeling complex. Mol. Cell 31, 909–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Collart M. A., Panasenko O. O. (2012) The Ccr4–not complex. Gene 492, 42–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Barnikol-Watanabe S., Gross N. A., Götz H., Henkel T., Karabinos A., Kratzin H., Barnikol H. U., Hilschmann N. (1994) Human protein NEFA, a novel DNA binding/EF-hand/leucine zipper protein. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the cDNA, isolation and characterization of the protein. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 375, 497–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Shi Y. J., Matson C., Lan F., Iwase S., Baba T., Shi Y. (2005) Regulation of LSD1 histone demethylase activity by its associated factors. Mol. Cell 19, 857–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Qian F., Kruse U., Lichter P., Sippel A. E. (1995) Chromosomal localization of the four genes (NFIA, -B, -C, and -X) for the human transcription factor nuclear factor I by FISH. Genomics 28, 66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kraemer D., Wozniak R. W., Blobel G., Radu A. (1994) The human CAN protein, a putative oncogene product associated with myeloid leukemogenesis, is a nuclear pore complex protein that faces the cytoplasm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 1519–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sheppard S. A., Loayza D. (2010) LIM-domain proteins TRIP6 and LPP associate with shelterin to mediate telomere protection. Aging 2, 432–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Petit M. M., Fradelizi J., Golsteyn R. M., Ayoubi T. A., Menichi B., Louvard D., Van de Ven W. J., Friederich E. (2000) LPP, an actin cytoskeleton protein related to zyxin, harbors a nuclear export signal and transcriptional activation capacity. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 117–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Altarejos J. Y., Montminy M. (2011) CREB and the CRTC co-activators: sensors for hormonal and metabolic signals. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 141–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Song L., Wang J., Liu J., Lu Z., Sui S., Jia W., Yang B., Chi H., Wang L., He S., Yu W., Meng L., Chen S., Peng X., Liang Y., Cai Y., Qian X. (2010) N-Glycosylation proteome of endoplasmic reticulum in mouse liver by ConA affinity chromatography coupled with LTQ-FT mass spectrometry. Science China Chemistry 53, 768–777 [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mason I. J., Taylor A., Williams J. G., Sage H., Hogan B. L. (1986) Evidence from molecular cloning that SPARC, a major product of mouse embryo parietal endoderm, is related to an endothelial cell ‘culture shock’ glycoprotein of Mr 43,000. EMBO J. 5, 1465–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Schimpl M., Schüttelkopf A. W., Borodkin V. S., van Aalten D. M. (2010) Human OGA binds substrates in a conserved peptide recognition groove. Biochem. J. 432, 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lamarre-Vincent N., Hsieh-Wilson L. C. (2003) Dynamic glycosylation of the transcription factor CREB: a potential role in gene regulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 6612–6613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rexach J. E., Clark P. M., Mason D. E., Neve R. L., Peters E. C., Hsieh-Wilson L. C. (2012) Dynamic O-GlcNAc modification regulates CREB-mediated gene expression and memory formation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 253–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Rached M. T., Kode A., Silva B. C., Jung D. Y., Gray S., Ong H., Paik J. H., DePinho R. A., Kim J. K., Karsenty G., Kousteni S. (2010) FoxO1 expression in osteoblasts regulates glucose homeostasis through regulation of osteocalcin in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 357–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yoshizawa T., Hinoi E., Jung D. Y., Kajimura D., Ferron M., Seo J., Graff J. M., Kim J. K., Karsenty G. (2009) The transcription factor ATF4 regulates glucose metabolism in mice through its expression in osteoblasts. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2807–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zachara N. E., Hart G. W. (2004) O-GlcNAc a sensor of cellular state: the role of nucleocytoplasmic glycosylation in modulating cellular function in response to nutrition and stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1673, 13–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.