Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer death in the US, and stage at diagnosis is the primary prognostic factor. To date, the interplay between geographic place and individual characteristics such as cancer stage with CRC survival is unexplored. We used a Bayesian geosurvival statistical model to evaluate whether the spatial patterns of CRC survival at the census tract level varies by stage at diagnosis (in situ/local, regional, distant), controlling for patient characteristics, surveillance test use, and treatment using linked 1991–2005 SEER-Medicare data of patients ≥ 66 years old in two US metropolitan areas. The spatial pattern of survival varied by stage at diagnosis for both cancer sites and registries. Significant spatial effects were identified in all census tracts for colon cancer and the majority of census tracts for rectal cancer. Geographic disparities appeared to be highest for distant-stage rectal cancer. Compared to those with in situ/local stage in the same census tracts, patients with distant-stage cancer were at most 7.73 times and 4.69 times more likely to die of colon and rectal cancer, respectively. Moreover, frailty areas for CRC at in situ/local stage more likely have a higher relative risk at regional stage, but not at distant stage. We identified geographic areas with excessive risk of CRC death and demonstrated that spatial patterns varied by both cancer type and cancer stage. More research is needed to understand the moderating pathways between geographic and individual-level factors on CRC survival.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Diagnosis stage, Geosurvival model, Geographic disparity

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer death in both men and women [1]. Research has demonstrated that individuals and geographic places with certain characteristics experience a disproportionate CRC burden [2]. For example, disparities in CRC survival have been observed by individual characteristics such as gender, race, and age, among others [3, 4], and an increasing number of studies have identified disparities in CRC survival across geographic areas and by neighborhood characteristics such as poverty rate [5–9].

To date, statistical limitations have hampered the study of geographic disparities in cancer survival and the reasons underlying these disparities. For example, the limited use of sophisticated spatial methods for survival analysis has prevented researchers from pinpointing exactly where disparities in survival are occurring. Conventional statistical methods used in cancer prevention and control research that examine geographic disparities are unable to adjust for spatial adjacency to estimate spatial variation and are often criticized for their inability to estimate independent neighborhood effects [10–13]. However, as the cluster detection method was developed to handle continuous survival data with different survival distribution functions, it had become the main epidemiological tools to test disease cluster in geographic areas [14].

In the last two decades, significant advances have been made to address these limitations in the study of geographic disparities in cancer survival and to identify where populations experience worse prognosis. Starting in the late 1990s, a Bayesian survival model was developed by incorporating an intrinsic conditional autoregressive term to obtain estimates from correlated neighboring areas [15, 16]. Subsequently, an unstructured exchangeable random effect was added to discrete-time or multilevel survival models to allow for examination of the spatial variability of hazard rates [17–19]. While the frequently used spatial scan statistic has been adapted to include spatial variation in time-to-event measurement [14], there are several issues that limit its functionality. These limitations include its inability to (1) perform risk assessments because it is not a model-based approach; (2) have geography interact with a prognostic factor; and (3) calculate smoothed risk estimates. Recently, a geosurvival model for continuous and discrete survival time was developed [20, 21], which includes a spatial component, nonparametric terms for both the log-baseline hazard rate and the smoothing function, and time-varying predictors [22, 23] thereby circumventing the aforementioned spatial scan statistics limitations. Mapping the spatial functions allows for the estimation and visualization of the magnitude of geographic disparity across geographic units within a study area in addition to displaying estimates of the spatial effects for these geographic units.

Using newly developed statistical models, evidence is starting to emerge that not everyone is affected by their residential geographic location to the same extent and that the extent of the effects of location may depend on individual characteristics [6, 24–28]. However, most studies have focused on the interplay between geographic location and sociodemographic characteristics of study participants [25, 26, 28]. In CRC, the primary prognostic factor is stage at diagnosis [29, 30], and CRC survival decreases significantly with advanced stage at diagnosis [31]. While geographic disparities have been identified in stage at diagnosis [32–34], likely as a function of geographic disparities in screening [6, 19, 35, 36], little is known about the interplay between stage at diagnosis and subsequent geographic disparities in CRC survival. We hypothesize that the spatial pattern of CRC survival varies by stage at diagnosis. Place-based stressors (e.g., higher psychosocial stress, lack of physical activity, high body-mass index, all factors that can cluster at a geographic level) may exacerbate the effect of stage at diagnosis on subsequent survival through increased inflammation and oxidative stress, the latter of which are also associated with CRC progression and survival [37–39].

If geographic location moderates the effect of cancer stage, the assumption that stage and geographic location at diagnosis independently affect prognosis will be called into question and the future of spatial and multilevel cancer epidemiology research will face additional complexity in both conceptualization and methodology. The potential implications of our approach for cancer prevention and control practitioners include the identification of distinct geographic areas experiencing disproportionate mortality as a function of stage, ultimately leading to context-specific interventions targeting the key factors driving local stage-specific disparities in survival. This study will examine the spatial variation in CRC survival as a function of disease stage. We hypothesize that (1) the magnitude of the spatial variation in CRC survival depends on stage at diagnosis after controlling for potential confounding factors, such as personal characteristics, surveillance test use, and type of treatment received, and (2) areas can be identified where CRC survival is significantly worse and the location of these areas will vary as a function of stage at diagnosis.

Methods

Data source

Data for this analysis were obtained from an existing linkage of the 1992–2005 National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program data with 1991–2005 Medicare claims files from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. The linked SEER-Medicare data provide detailed clinical information for Medicare patients included in SEER, a nationally representative collection of population-based cancer registries [40]. Ninety-four percent of cancer patients reported to SEER aged 66 years or older have been linked successfully with Medicare claims data. Patient follow-up data were collected by hospital-based and population-based registries depending on the size of the hospital. Follow-up policies and procedures were monitored by the governing body of the cancer registry. Different registries have similar follow-up procedures [41]. This study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University and determined to be exempt from IRB oversight. Because of potential confidentiality concerns by the National Cancer Institute, we are unable to identify either of these registries by name when we map our results. Instead, we refer to them as Registry I and II.

Study area

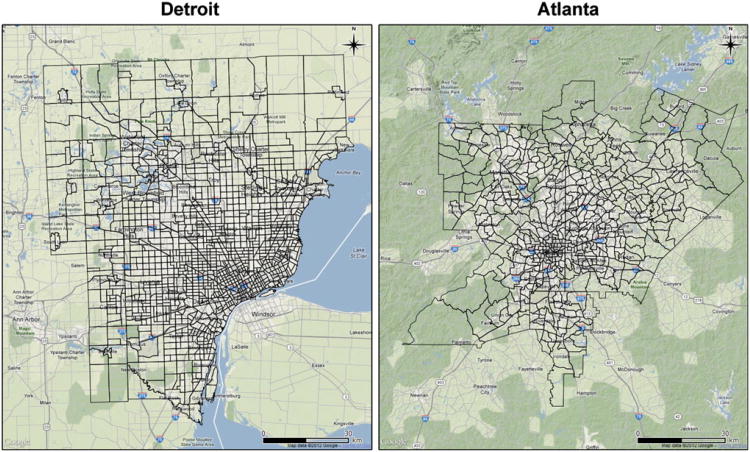

We used two metropolitan SEER registries (Detroit and Atlanta) as illustrations of our analyses, and census tract is used as the geographic unit in this study because it is relatively homogenous with respect to population characteristics, economic status, and living conditions [42]. All street addresses regardless of the date of diagnosis were geocoded to the year 2000 TIGER file and census tract geography. A census tract is a small geographic subdivision in a county with 2,500–8,000 residents. Detroit is the largest city in Michigan and the 18th most populous city in the US. The Detroit SEER registry collects data about cancer patients from 1,163 census tracts in three counties (Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne). The Atlanta metropolitan area is the largest metropolitan area from which the SEER registry collects data in the Southern US since 1974. It includes five counties (Cobb, Fulton, Clayton, Dekalb, and Gwinnett) representing 478 census tracts. The two areas have relatively similar shapes, where the total land area of metropolitan Detroit and Atlanta are 5,094.8 and 3,604.3 km2, respectively (Fig. 1). Detroit and Atlanta have an average for 6,097.46 and 3,470.79 inhabitants in each census tract based on the 2000 Census, respectively. The average proportion of the population aged 66 or older was 12.7 % in Atlanta and 8.1 % in Detroit, respectively. The two SEER metropolitan areas were chosen based on their relatively large African American population to ensure a diverse population within each area to maximize potential geographic variability and to allow for all census tracts to be contained in contiguous geographic areas.

Fig. 1. Census tracts of Detroit and Atlanta, according to Google Maps, retrieved May 18, 2012 from http://maps.google.com.

Study population

The study population was comprised of cancer patients aged 66 or older diagnosed with a first primary tumor of the colon or rectum (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology ICD-O codes C18.0–C20.9) [43] in Detroit and Atlanta from 1992 through 2005. Only CRC patients who had continuous Medicare part A and B coverage and were not enrolled in a Health Maintenance Organization were included in the analysis.

Variable definitions

The selected individual-level variables included in the geosurvival analysis are established predictors of survival [44, 45]: race (White, Black), sex (male, female), Charlson comorbidity score (0, 1, 2+) [46], disease history (yes, no), surveillance colonoscopy during 3 years after diagnosis (yes, no), radiation (yes, no), surgery (yes, no), chemotherapy (yes, no), age at diagnosis (continuous), and SEER summary stage at diagnosis (in situ/local stage, regional stage, distant stage). Disease history is defined by any personal or family history of inflammatory bowel disease, colon polyps, or bowel disease (yes, no) identified using ICD-9 codes found in Medicare claims from 1991 to 2005. Except for stage at diagnosis, sex, and race which were obtained from the SEER data, all variables were constructed using Medicare claims data and were based on previous studies [47, 48].

The location of the patient's residence at time of diagnosis was geocoded to a census tract because they are relatively homogeneous with respect to living conditions, socioeconomic status, and population characteristics [35]. There were initially 15,639 CRC patients located in the two study areas; of whom 15,273 patients (97.7 %) were assigned a census tract using street addresses, 299 using ZIP codes, 52 using other geographic information, and 15 were not assigned a census tract. Patients with unknown information on any of the variables described above (6,586 cases) or missing census tract (15 cases) were excluded. The final analysis included 9,038 CRC patients from both registries in our sample.

Statistical analysis

In conventional survival analysis, data are usually denoted by (ti, δi, xi) for patient i, who has a survival time Ti and a right censoring time Ci. Hence, the observed time is defined as ti = min(Ti, Ci), and δi is an index of censoring, where 1 denotes death, and 0 for otherwise. For colon or rectal cancer-specific survival, the definition of δi is 1 for colon or rectal cancer death and 0 for patients who were alive or who died of non-colon cancer or non-rectal cancer deaths. The vector xi contains linear factors for gender, race, comorbidity, disease history, colonoscopy, radiation, surgery, chemotherapy, and age at diagnosis. Therefore, a survival analysis in terms of the Cox PH model [49] can be established by:

Model I

log[h(ti, xi)] = log[h0(ti) ] +xiβ

Here, log[h0(ti)] is the log-baseline function. In our geosurvival modeling approach, the notation of survival data is expanded to (ti, δi, xi, si), where si represents the location of the patient's residence. Hence, Model I can be expanded to:

Model II

log[h(ti, xi, si)] = log[h0(ti) ] + xiβ+ fspat(si) where fspat(Si) denotes the spatial function, which is defined as a structured component for geographic information of the census tract. The spatial function is implemented using Markov random fields [50], which has a Normal prior denoted by:

where is defined as a neighbor adjacent to location si, and ωsi is a set of neighbors of location si. Hence, the number of neighbors in the set of ωsi is denoted by Nsi. The unknown variance parameter follows an inverse Gamma distribution IG(a, b) with two assigned hyperparameters a = 0.001 and b = 0.001. The log-baseline function h0(ti) is modeled by a cubic P-spline prior with 20 knots.

To investigate the extent to which the spatial effect depends on stage at diagnosis, we expand Model II to a goesurvival model using census tract as an effect modifier:

Model III

log[h(ti, xi, si)] = log[h0(ti)] + xiβ + fspat.1(si) + SDreg × fspat.2(si) + SDdis × fspat.3(si)

Here, fspat.1, fspat.2, and fspat.3 are the spatial functions for patients diagnosed with in situ/local stage, regional stage, and distant stage, respectively. Stage at diagnosis is coded using two dummy variables, SDreg (coded 1 if regional stage and 0 otherwise) and SDdis (coded 1 if distant stage and 0 otherwise). The mathematical attributes of the three spatial functions in Model III are identical to Model II.

The statistical inference for all unknown parameters is based on a fully Bayesian approach using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation by updating full conditional distributions of the parameters in two blocks, using a Metropolis-Hastings algorithm for the baseline function as well as all spline terms [51, 52] and adopting a Gibbs sampling scheme for the precision parameters [20]. For each model, 25,000 iterations were carried out, with the first 5,000 samples used as a burn-in. We stored every 20th sample from the remaining 20,000 samples, giving a final sample of 1,000 for constructing the posterior distribution for each of the parameter estimates. Also, corresponding 95% credible intervals (CI), which is a synonym of confidence intervals used in frequentist statistics, were calculated based on the posterior distribution of the 1,000 samples. Hazard ratios (HR) for risk factors were calculated by exponentiating parameter estimates. The exponential spatial function can be regarded as the frailty variable in Model II [16], so the exponential estimated spatial effect in each census tract can be interpreted as the relative risk (RR) for CRC. When the spatial function interacts with stage at diagnosis in Model III, the explanation of the spatial function for the reference level (i.e., in situ/local stage) is generally the same as Model II; however, for regional stage and distant stage, their exponential spatial functions should be interpreted as the number of times the RR increases or decreases from in situ/local stage. This is similar to a study using cancer registry data by Musio et al. [53].

The exponentiation of the standard deviation of the spatial function can be explained as the average variation of RR among census tracts. That is, the census tract risk of CRC is on average about larger or smaller than the overall CRC risk, reflecting the level of geographic disparities of census tract aggregation of CRC [54]. To reduce confidentiality concerns, maps display the smoothed surface of the spatial effects for each stage at diagnosis based on a simple kriging method [55] to interpolate across census tracts within each registry. The kriging model Yk = Pk + Zk + ek was used where Yk is a dependent variable representing the spatial estimate derived from Model III at location k, Pk is a low-order polynomial function, Zk is a Gaussian field with mean zero and covariance function Σ, and ek is an independent normal error. The interpolated estimates is the best linear unbiased estimate of Pk + Zk given the estimated spatial function from Model III. The spatial data in location k used the longitude and latitude of the centroid data. Hence, the smoothed maps depict the general spatial pattern while the location of patients' residences is protected.

We assessed the fit of the 3 models using the deviance information criterion (DIC) [56]. A smaller DIC denotes a better model fit, with changes in the DIC of at least 7 being in favor of a superior model choice. Statistical significance for HR and RR was determined by the 95% confidence interval not containing one. The geographic disparity was calculated by squaring the spatial variance. All models were implemented in BayesX v2.01 [57], and all maps were created using the fields package in R v2.14.1 software [58].

Results

Characteristics of the study population and areas

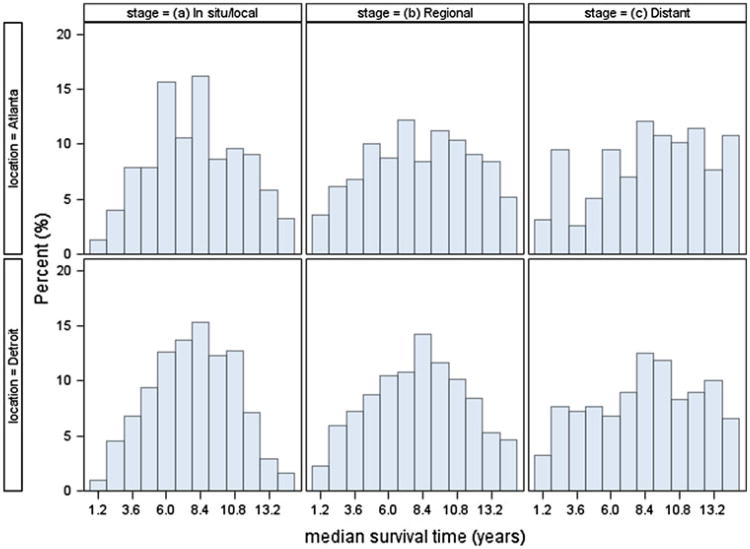

Table 1 shows patient characteristics by stage at diagnosis. All of the characteristics varied statistically by stage at diagnosis except for sex. Overall, survival declined with increasing stage at diagnosis. Figure 2 shows that the distribution of census tract level median survival times in years after diagnosis varied by stage in both SEER areas. As expected, the number of census tracts with available median survival time was lower for more advanced stage based on the number of CRC patients available. Of the 1,641 census tracts in the two study areas, there were 1,530 tracts (93.2 %) with at least one CRC patient in at least one stage group.

Table 1. Patient characteristics by stage at diagnosis in SEER Detroit and Atlanta areas, 1992–2005.

| In situ/local (N = 5598, % = 61.9) | Regional (N = 2578, % = 28.5) | Distant (N = 862, % = 9.5) | p valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 2277 (40.7)a | 1056 (41.0) | 380 (44.0) | 0.1648 |

| Female | 3321 (59.3) | 1522 (59.0) | 482 (55.9) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 4613 (82.4) | 2098 (81.4) | 663 (76.9) | 0.0005 |

| Black | 985 (17.6) | 480 (18.6) | 199 (23.1) | |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| 2+ | 964 (17.2) | 407 (15.8) | 127 (14.7) | 0.0006 |

| 1 | 1487 (26.6) | 636 (24.7) | 189 (21.9) | |

| 0 | 3147 (56.2) | 1535 (59.5) | 546 (63.3) | |

| Disease history | ||||

| Yes | 371 (6.6) | 153 (5.9) | 28 (3.3) | 0.0005 |

| No | 5227 (93.4) | 2425 (94.1) | 834 (96.8) | |

| Colonoscopy | ||||

| Yes | 2619 (46.8) | 1136 (44.1) | 374 (43.4) | 0.0262 |

| No | 2979 (53.2) | 1442 (55.9) | 488 (56.6) | |

| Radiation | ||||

| Yes | 372 (6.7) | 363 (14.1) | 88 (10.2) | <.0001 |

| No | 5226 (93.4) | 2215 (85.9) | 774 (89.8) | |

| Surgery | ||||

| Yes | 5514 (98.5) | 2567 (99.6) | 753 (87.4) | <.0001 |

| No | 84 (1.5) | 11 (0.4) | 109 (12.7) | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 874 (15.6) | 1558 (60.4) | 547 (63.5) | <.0001 |

| No | 4724 (84.4) | 1020 (39.6) | 315 (36.5) | |

| Cause-specific death | ||||

| Colon cancer | 549 (9.8) | 769 (29.8) | 558 (64.7) | <.0001 |

| Rectal cancer | 88 (1.6) | 125 (4.9) | 77 (8.9) | |

| Other causes/alive | 4961 (88.6) | 1684 (65.3) | 227 (26.3) | |

| Age at diagnosis | 76.7 (6.6)b | 76.0 (6.4) | 74.8 (6.3) | <.0001 |

Number of cases (percentage)

Mean (Standard deviation)

p value is generated by chi-square test for the categorized variables (sex, race, comorbidity, disease history, colonoscopy, radiation, surgery, chemotherapy, cause-specific death) and F test for the continuous variable (age at diagnosis)

Fig. 2. Distribution of median survival time at the census tract level after diagnosis by stage in Detroit and Atlanta.

Geosurvival analysis

Table 2 shows that the difference in goodness of fit between models I (i.e., with no spatial function) and II (i.e., with a spatial function) is negligible, but that model III (i.e., with spatial functions by stage interaction) fits substantially better (ΔDIC > 7) than either model, suggesting that the spatial effects vary by stage at diagnosis. This is the case for both colon and rectal cancer in both registries.

Table 2. DIC of models.

| Modela | Colon cancer | Rectal cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| D(θˉ) | pD | DIC | ΔDICb | D(θˉ) | pD | DIC | ΔDIC | |

| Detroit | ||||||||

| I | 10630.4 | 21.8 | 10674.0 | – | 2216.5 | 19.0 | 2254.5 | – |

| II | 10605.7 | 33.7 | 10673.1 | 0.9 | 2202.4 | 26.3 | 2255.0 | 0.5 |

| III | 10021.5 | 57.3 | 10136.0 | 538.0 | 2128.6 | 39.8 | 2208.2 | 46.3 |

| Atlanta | ||||||||

| I | 3518.1 | 21.1 | 3560.3 | – | 888.1 | 15.7 | 919.5 | – |

| II | 3509.2 | 26.1 | 3561.4 | 1.1 | 865.5 | 26.4 | 918.3 | 1.2 |

| III | 3362.7 | 44.8 | 3452.3 | 108.0 | 849.2 | 28.3 | 905.8 | 13.7 |

Model I = log-baseline function + confounding variables (race, sex age at diagnosis, comorbidity, disease history, colonoscopy, radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy); Model II = log-baseline function + confounding variables + spatial function; Model III = log-baseline function + confounding variables + spatial function × stage at diagnosis

Model assessment statistics: D(θˉ) = the posterior mean of the deviance; pD = the effective number of parameters; DIC = deviance information criterion; ADIC = the absolute difference of DIC between model III and the other two models

In Detroit, the following factors significantly increased the risk of death following colon cancer for patients regardless of stage (Table 3): Black race, more comorbidities, having a disease history, having received chemotherapy, and increasing age. Same significant factors were found in Atlanta, except for comorbidity and disease history. Table 4 shows the following factors significantly increased the risk of death for rectal cancer patients in all stages in Detroit: male sex, having received radiation, and increasing age, while only having had surgery significantly reduced the risk of death among rectal cancer patients. In Atlanta, none of these factors were associated with survival in rectal cancer patients, except for surgery.

Table 3. Hazard ratio with 95% credible interval for sex, race, comorbidity, disease history, colonoscopy, radiation, surgery, chemotherapy, and age at diagnosis for colon cancer in Detroit and Atlanta, 1992–2005.

| Detroit | Atlanta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male versus female | 1.02 | (0.91, 1.12) | 1.03 | (0.85, 1.25) |

| Race | ||||

| Black versus White | 1.32 | (1.13, 1.58)* | 1.30 | (1.02, 1.63)* |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| 2+ versus 0 | 1.46 | (1.26, 1.70)* | 1.18 | (0.87, 1.55) |

| 1 versus 0 | 1.23 | (1.08, 1.40)* | 1.07 | (0.83, 1.36) |

| Disease history | ||||

| Yes versus No | 2.27 | (1.68, 2.99)* | 1.17 | (0.62, 2.10) |

| Colonoscopy | ||||

| Yes versus No | 0.93 | (0.84, 1.04) | 0.95 | (0.78, 1.16) |

| Radiation | ||||

| Yes versus No | 1.00 | (0.83, 1.20) | 0.93 | (0.66, 1.28) |

| Surgery | ||||

| Yes versus No | 1.04 | (0.75, 1.43) | 0.59 | (0.40, 0.93) |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes versus No | 1.17 | (1.04, 1.33)* | 1.24 | (1.00, 1.56)* |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.02 | (1.01, 1.03)* | 1.01 | (1.00, 1.03)* |

HR hazard ratio, CI credible interval

Statistically significance

Table 4. Hazard ratio with 95% credible interval for sex, race, comorbidity, disease history, colonoscopy, radiation, surgery, chemotherapy, and age at diagnosis for rectal cancer in Detroit and Atlanta 1992–2005.

| Detroit | Atlanta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male versus Female | 1.51 | (1.14, 1.98)* | 0.53 | (0.32, 1.08) |

| Race | ||||

| Black versus White | 1.13 | (0.73, 1.71) | 1.55 | (0.90, 2.96) |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| 2+ versus 0 | 0.86 | (0.53, 1.31) | 0.81 | (0.38, 1.65) |

| 1 versus 0 | 1.02 | (0.72, 1.44) | 0.63 | (0.32, 1.25) |

| Disease history | ||||

| Yes versus No | 1.88 | (0.75, 4.07) | 2.28 | (0.67, 5.83) |

| Colonoscopy | ||||

| Yes versus No | 1.26 | (0.95, 1.68) | 0.73 | (0.48, 1.13) |

| Radiation | ||||

| Yes versus No | 4.92 | (3.50, 6.99)* | 5.35 | (0.77, 9.10) |

| Surgery | ||||

| Yes versus No | 0.24 | (0.14, 0.39)* | 0.39 | (0.18, 0.92)* |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes versus No | 0.92 | (0.65, 1.28) | 1.17 | (0.74, 2.45) |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.03 | (1.01, 1.06)* | 0.98 | (0.95, 1.03) |

HR hazard ratio, CI credible interval

Statistically significance

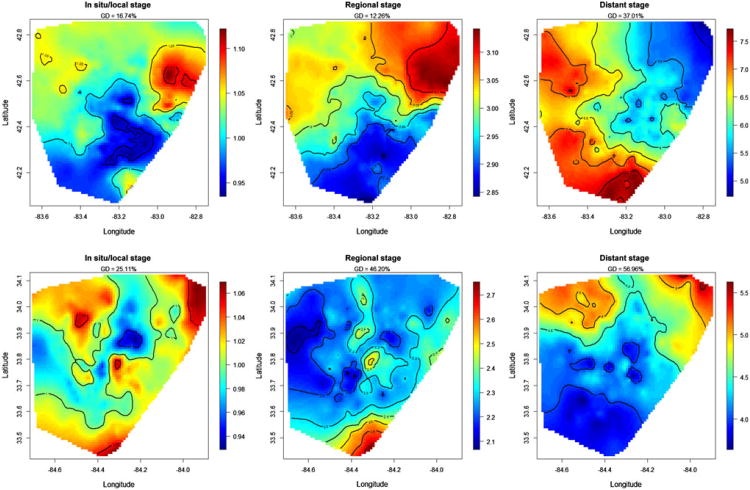

Figure 3 shows the interaction between the structured spatial effect and stage at diagnosis for colon cancer based on Model III for each registry. Distant stage had the largest geographic disparity percentage, at a high of 56.96 %. For in situ/localized colon cancer, the areas with higher risk of death (lowest survival) accounted for about half of the geographic area of each registry, and the highest risk areas were concentrated in the northwestern parts of both Detroit and Atlanta, and a part of southern Atlanta. The RR was elevated in all census tracts in both registries at regional and distant stages relative to in situ/localized colon cancer, indicating that such patients had worse survival than in situ/localized colon cancer patients in all census tracts. For regional colon cancer, higher RR highlighted by red and brown colors was present in the northeast and southern census tracts of the registries. Patients diagnosed with regional colon cancer in these census tracts were up to 3.14 times (95% CI = 2.57, 4.15) more likely to die compared to patients with in situ/localized colon cancer in the same census tracts. A different spatial pattern was observed for distant-stage colon cancer patients, with higher RRs in the western and northern part of two registries compared to regional-stage disease. Colon cancer patients diagnosed with distant disease were at least 3.50 times (95% CI = 1.33, 5.60) and up to 7.73 times (95% CI = 5.06, 15.04) more likely to die than patients diagnosed with in situ/localized colon cancer in the same tracts. For 46.9 % of census tracts, patients diagnosed with distant colon cancer were equally likely to die as those who were diagnosed with regional colon cancer in these same census tracts.

Fig. 3. Maps of relative risks (RR) for colon cancer by stage at diagnosis in both SEER registries, calculated by the exponential spatial function. Brown represents higher RR, and blue represents lower RR. The geographic disparity (GD) for each map is calculated by exponentiating the square root of the spatial variance.

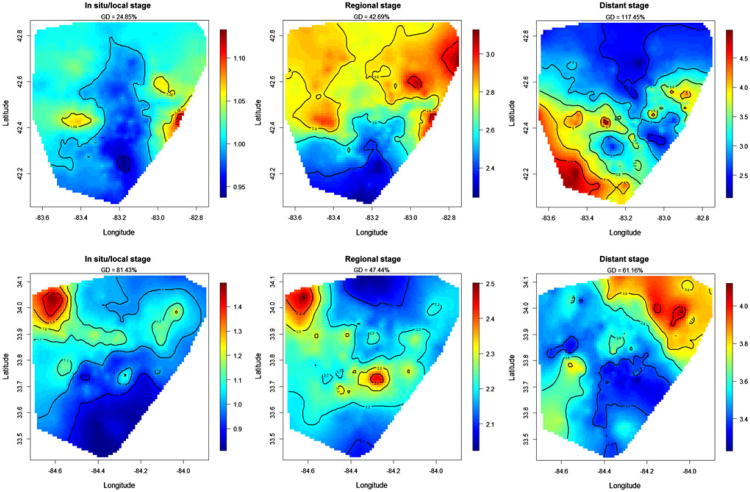

The spatial patterns by stage at diagnosis were different for rectal cancer, as compared to colon cancer, for both registries (Fig. 4). Geographic disparities were observed at all three stages at diagnosis for rectal cancer and can elevate to at most 117.45 % at distant stage. For in situ/local stage, the RR was distributed almost uniformly across both registries, except for a larger concentration near the northeastern area in one of the registries. For regional-stage rectal cancer, the RR was at least 2.02 times (95% CI = 0.65, 4.08) and up to 3.18 times (95% CI = 1.86, 7.67) higher than for in situ/localized rectal cancer in the same census tracts. A concentration of the greatest elevation of the RR appeared in the northeastern and northwestern areas in both registries. For 14.9 % of the census tracts, there was no statistical difference in survival between regional and in situ/localized rectal cancer. For distant-stage rectal cancer, the RR was at least 2.03 times (95% CI = 0.54, 4.69) and up to 4.69 times (95% CI = 1.26, 27.28) higher than for in situ/localized rectal cancer in the same census tracts. For 42.2 % of census tracts, there was no survival difference between distant and in situ/localized rectal cancer.

Fig. 4. Maps of relative risks (RR) for rectal cancer by stage at diagnosis in both SEER registries, calculated by the exponential spatial function. Brown represents higher RR, and blue represents lower RR. The geographic disparity (GD) for each map is calculated by exponentiating the square root of the spatial variance.

Discussion

While studies have shown that CRC survival varies geographically [35, 47, 59], there are no studies that have examined and observed that the residential location of CRC patients modified the well-established association between stage at diagnosis and survival. Our findings show that the spatial patterns of survival varied by disease stage after adjusting for patient, tumor, treatment, and surveillance characteristics. For several census tracts, we demonstrate that patients with more advanced stage at diagnosis had similar survival as those with in situ/local stage. We also demonstrate that the spatial patterns that identified geographic areas as having either relatively lower or higher survival varied between colon cancer and rectal cancer within the same SEER registry. Moreover, frailty areas with higher RR for CRC at in situ/local stage seem to be more tractable at regional stage than distant stage because we found similar concentrations of the greatest elevation of the RR appeared at regional stage in both registries, but those concentrations moved to other areas at distant stage. Importantly, we also revealed geographic disparities for patients explicitly varied in different stages at diagnosis for both colon and rectal cancers, and the greatest geographic disparities most likely happened at distant stage.

Previous spatial analyses showed that CRC survival varied geographically across demographic subgroups [6, 59], but we now show that where CRC patients live may differentially impact the effect of tumor stage on survival. One mechanism by which stage at diagnosis and geography could interact to affect survival is through the biological processes of increased inflammation and oxidative stress [37]. Higher inflammation and production of free radicals resulting in increased oxidative stress and associated responses adversely affect survival and both are associated with more advanced stage at diagnosis [37, 60, 61]. Features of geographic areas (e.g., lack of fruit/vegetable availability and/or features of the built environment promoting physical activity) may increase inflammation and/or oxidative stress by means of lower participation in health-related behaviors (e.g., healthy diet, physical activity) or their consequences (e.g., body-mass index) [39, 62, 63]. Elevated place-based psychosocial stress may also affect inflammation and oxidative stress and thereby CRC survival [64–66]. Focusing on inflammation and oxidative stress to improve survival may provide opportunities for intervention based on the location of residence and stage at diagnosis. For example, specific types of patients (e.g., those with more advanced stage) in selected locations could reduce their inflammation and oxidative stress by participating in physical activities, quitting smoking, reducing alcohol consumption, or using aspirin and as a result have similar survival as those with in situ/localized disease [67]. Other possible mechanisms include differential responses by stage of disease to the local health care environment including the quantity, quality, accessibility, or affordability of clinical medical care and treatment options, such as the availability of National Cancer Institute designed cancer centers. Given the variables available in this dataset and included in our statistical model (age, race, sex, comorbidity, disease history, type of treatment received, and surveillance colonoscopy), we cannot test these hypothesized mechanisms underlying the moderating effect stage and location of residence.

We demonstrated several key advantages of the geosurvival model compared to traditional spatial, multi- or single-level regression or survival analyses, or other spatial approaches to geographic risk detection. First, the geosurvival model incorporates spatial effects, controlling for the spatial autocorrelation of the outcome if it exists. The flexibility of this model also allows for the inclusion of linear or nonlinear confounders [21, 68, 69]. Second, by using this model, we were able to generate multiple maps that identified the location of differing levels of relative risk as well as the corresponding credible intervals to demonstrate significance of observed differences. Unlike frequentist approaches, the use of MCMC simulation is appropriate in small samples including in some census tracts with only a few CRC patients [70]. Third, our geosurvival models estimated the magnitude of the geographic disparity in survival following patients' diagnosis with colon or rectal cancer.

Our results should be interpreted in light of four potential limitations. First, our sample included only patients ≥ 66 years old, those insured with Medicare parts A and B, without HMO coverage, and those living in two SEER areas thereby limiting generalizability to these populations. Second, our analysis was limited to variables available in the SEER-Medicare dataset. Third, some limitations should also be noted regarding our application of the geosurvival model. The log-baseline effect estimated by a P-spline might be of a different parametric form, such as a Weibull or a Gamma distribution, but software for assigning such baseline functions is still unavailable. Fourth, potential changes in residential address during the period of follow-up for each patient were unknown, which may have biased our findings if such changes varied by stage at diagnosis.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, we present the first application of a geosurvival model for CRC survival. We demonstrated geographic disparities in CRC survival and document a variable spatial pattern of disparities by disease stage. Using direct visualization of the model parameters in a series of maps, we were able to identify geographic areas with a lower or higher relative risk of survival separately by stage. Notably, we demonstrated a greater geographic disparity at more distant stages of disease for both colon and rectal cancer. More research is needed to understand the complex interplay between geographic and individual-level factors on health outcomes. Geospatial analyses such as ours hold promise to change how population-based cancer prevention and control research is conducted and to whom and where future interventions are deployed in order to eliminate geographic disparities in cancer outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge James Struthers for his data management and programming services. We thank the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, for the use of the Health Behavior, Communications, and Outreach Core. This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number CA112159); and the Health Behavior, Communication and Outreach Core; the Core is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (grant number P30 CA91842) to the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. SLP was supported by the National Center for Research Resources Washington University-ICTS (grant number KL2 RR024994).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. The funders did not have any role in the design of the study; the analysis and interpretation of the data; the decision to submit the manuscript for publication; or the writing of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Lung-Chang Chien, Email: lchien@dom.wustl.edu, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Health Behavior, Research, Washington University School of Medicine, 4444 Forest Park Avenue, Suite 6700, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Mario Schootman, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Health Behavior, Research, Washington University School of Medicine, 4444 Forest Park Avenue, Suite 6700, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Sandi L. Pruitt, Department of Clinical Sciences, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Simmons Cancer Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390, USA

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taplin SH, Haggstrom D, Jacobs T, Determan A, Granger J, Montalvo W, et al. Implementing colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: addressing cancer health disparities through a regional cancer collaborative. Med Care. 2008;46:S74–S83. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fdf68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander DD, Waterbor J, Hughes T, Funkhouser E, Grizzle W, Manne U. African-American and Caucasian disparities in colorectal cancer mortality and survival by data source: an epidemiologic review. Cancer Biomar. 2007;3:301–313. doi: 10.3233/cbm-2007-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Haug U. Gender differences in colorectal cancer: implications for age at initiation of screening. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:828–831. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, Singh GK, Cardinez C, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socio-economic status. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu CE, Mas FS, Hickey JM, Miller JA, Lai D. Surveillance of the colorectal cancer disparities among demographic subgroups: a spatial analysis. South Med J. 2006;99:949–956. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000224755.73679.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernandez MN, Roy Chowdhury R, Fleming LE, Griffith DA. Colorectal cancer and socioeconomic status in Miami-Dade County: neighborhood-level associations before and after the Welfare Reform Act. Appl Geogr. 2011;31:1019–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naishadham D, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Siegel R, Cokkinides V, Jemal A. State disparities in colorectal cancer mortality patterns in the United States. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2011;20:1296–1302. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semrad TJ, Tancredi DJ, Baldwin LM, Green P, Fenton JJ. Geographic variation of racial/ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer testing among medicare enrollees. Cancer. 2011;117:1755–1763. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-Carr D, Davis J, Jankowska MM, Grant L, López-Carr AC, Clark M. Space versus place in complex human– natural systems: spatial and multi-level models of tropical land use and cover change (LUCC) in Guatemala. Ecol Model. 2012;229:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diez-Roux AV. Bringing context back into epidemiology: variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:216–222. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oakes JM. The (mis)estimation of neighborhood effects: causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1929–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaix B, Merlo J, Chauvin P. Comparison of a spatial approach with the multilevel approach for investigating place effects on health: the example of healthcare utilisation in France. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2005;59:517–526. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.025478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang L, Kulldorff M, Gregorio D. A spatial scan statistic for survival data. Biometrics. 2007;63:109–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osnes K, Aalen OO. Spatial smoothing of cancer survival: a Bayesian approach. Stat Med. 1999;18:2087–2099. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990830)18:16<2087::aid-sim186>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banerjee S, Wall MM, Carlin BP. Frailty modeling for spatially correlated survival data, with application to infant mortality in Minnesota. Biostatistics. 2003;4:123–142. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adebayo SB, Fahrmeir L. Analysing child mortality in Nigeria with geoadditive discrete-time survival models. Stat Med. 2005;24:709–728. doi: 10.1002/sim.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crook AM, Knorr-Held L, Hemingway H. Measuring spatial effects in time to event data: a case study using months from angiography to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) Stat Med. 2003;22:2943–2961. doi: 10.1002/sim.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lian M, Schootman M, Doubeni CA, Park Y, Major JM, Torres Stone RA, et al. Geographic variation in colorectal cancer survival and the role of small-area socioeconomic deprivation: a multilevel survival analysis of the NIH-AARP diet and health study cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:828–838. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hennerfeind A, Brezger A, Fahrmeir L. Geoadditive survival models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2006;101:1065–1075. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofner B, Kneib T, Hartl W, Küchenhoff H. Building Cox-type structured hazard regression models with time-varying effects. Stat Model. 2011;11:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hennerfeind A, Held L, Sauleau EA. A Bayesian analysis of relative cancer survival with geoadditive models. Stat Model. 2008;8:117–139. doi: 10.1002/sim.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandala NB, Ghilagaber G. A geo-additive bayesian discrete-time survival model and its application to spatial analysis of childhood mortality in Malawi. Qual Quant. 2006;40:935–957. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doubeni CA, Schootman M, Major JM, Torres Stone RA, Laiyemo AO, Park Y, et al. Health status, neighborhood socioeconomic context, and premature mortality in the United States: the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Public Health. 2011;102(4):680–688. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivory VC, Collings SC, Blakely T, Dew K. When does neighbourhood matter? Multilevel relationships between neighbourhood social fragmentation and mental health. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1993–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matheson FI, White HL, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Glazier RH. Drinking in context: the influence of gender and neighbourhood deprivation on alcohol consumption. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2012;66(6):e4. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.112441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schootman M, Andresen EM, Wolinsky FD, Miller JP, Yan Y, Miller DK. Neighborhood conditions, diabetes, and risk of lower-body functional limitations among middle-aged African Americans: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:283. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winkleby M, Cubbin C, Ahn D. Effect of cross-level interaction between individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on adult mortality rates. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2145–2153. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcella S, Miller JE. Racial differences in colorectal cancer mortality: the importance of stage and socioeconomic status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:359–366. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz KL, Crossley-May H, Vigneau FD, Brown K, Banerjee M. Race, socioeconomic status and stage at diagnosis for five common malignancies. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:761–766. doi: 10.1023/a:1026321923883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2008. [Assessed 21 May 2012];2012 Available: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/

- 32.DeChello LM, Sheehan TJ. Spatial analysis of colorectal cancer incidence and proportion of late-stage in Massachusetts residents: 1995–1998. Int J Health Geogr. 2007;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elferink MA, Pukkala E, Klaase JM, Siesling S. Spatial variation in stage distribution in colorectal cancer in the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer. 2011;48(8):1119–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rushton G, Peleg I, Banerjee A, Smith G, West M. Analyzing geographic patterns of disease incidence: rates of late-stage colorectal cancer in Iowa. J Med Syst. 2004;28:223–236. doi: 10.1023/b:joms.0000032841.39701.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henry KA, Niu X, Boscoe FP. Geographic disparities in colorectal cancer survival. Int J Health Geogr. 2009;8:48. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schootman M, Lian M, Deshpande A, McQueen A, Pruitt S, Jeffe D. Temporal trends in geographic disparities in small-area-level colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:1173–1181. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9796-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung EY, Crozier JE, Talwar D, O'Reilly DS, McKee RF, Horgan PG, et al. Vitamin antioxidants, lipid peroxidation, tumour stage, the systemic inflammatory response and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2460–2464. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skrzydlewska E, Sulkowski S, Koda M, Zalewski B, Kanczuga-Koda L, Sulkowska M. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:403–406. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vrieling A, Kampman E. The role of body mass index, physical activity, and diet in colorectal cancer recurrence and survival: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:471–490. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Cancer Institute. SEER Training Modules. [Assessed 19 Oct 2012];2012 Avariable from http://training.seer.cancer.gov/followup/

- 42.U.S. Census Bureau. [Assessed 15 Oct 2012];Geographic Areas Reference Manual. 2012 Available from http://www.census.gov/geo/www/GARM/Ch10GARM.pdf.

- 43.Fritz AG. International classification of diseases for oncology: ICD-O. 3rd. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodgson DC, Fuchs CS, Ayanian JZ. Impact of patient and provider characteristics on the treatment and outcomes of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:501–515. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.7.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polite BN, Dignam JJ, Olopade OI. Colorectal cancer model of health disparities: understanding mortality differences in minority populations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2179–2187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomez SL, O'Malley CD, Stroup A, Shema SJ, Satariano WA. Longitudinal, population-based study of racial/ethnic differences in colorectal cancer survival: impact of neighborhood socioeconomic status, treatment and comorbidity. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salz T, Weinberger M, Ayanian JZ, Brewer NT, Earle CC, Elston Lafata J, et al. Variation in use of surveillance colonoscopy among colorectal cancer survivors in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:256. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cox D, Oakes D. Analysis of survival data. Chapman and Hall; London: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kindermann R, Snell JL. Markov random fields and their applications. American Mathematical Society, Providence 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gamerman D. Sampling from the posterior distribution in generalized linear mixed models. Stat Comput. 1997;7:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knorr-Held L. Conditional prior proposals in dynamic models. Scand J Stat. 1999;26:129–144. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Musio M, Sauleau EA, Buemi A. Bayesian semi-parametric ZIP models with space-time interactions: an application to cancer registry data. Math Med Biol. 2010;27:181–194. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dqp025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pankratz VS, Andrade MD, Therneau TM. Random-effects Cox propotional hazards model: general variance components methods for time-to-event data. Genetic Epidemiol. 2005;28:97–109. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cressie N. Statistics for spatial data. Wiley; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, Van Der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J Roy Stat Soc B. 2002;64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belitz C, Brezger A, Kneib T, Lang S. BayesX: Software for Bayesian inference in structured additive regression models. Version 2.01. [Assessed 21 May 2012];2012 Available from: http://www.stat.uni-muenchen.de/∼bayesx.

- 58.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gorey KM, Luginaah IN, Bartfay E, Fung KY, Holowaty EJ, Wright FC, et al. Effects of socioeconomic status on colon cancer treatment accessibility and survival in Toronto, Ontario, and San Francisco, California, 1996–2006. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:112–119. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McMillan DC, Canna K, McArdle CS. Systemic inflammatory response predicts survival following curative resection of colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:215–219. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:149–163. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schulz AJ, Mentz G, Lachance L, Johnson J, Gaines C, Israel BA. Associations between socioeconomic status and allostatic load: effects of neighborhood poverty and tests of mediating pathways. Am J Public Health. 2012:e1–e6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load bio-markers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:901–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor L, Loerbroks A, Herr RM, Lane RD, Fischer JE, Thayer JF. Depression and smoking: mediating role of vagal tone and inflammation. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42:334–340. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin use and survival after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:649–658. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sauleau EA, Hennerfeind A, Buemi A, Held L. Age, period and cohort effects in Bayesian smoothing of spatial cancer survival with geoadditive models. Stat Med. 2007;26:212–229. doi: 10.1002/sim.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Strasak AM, Lang S, Kneib T, Brant LJ, Klenk J, Hilbe W, et al. Use of penalized splines in extended Cox-type additive hazard regression to flexibly estimate the effect of time-varying serum uric acid on risk of cancer incidence: a prospective, population-based study in 78,850 men. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dunson DB. Commentary: practical advantages of bayesian analysis of epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:1222–1226. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.12.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]