Abstract

PURPOSE

Intraarterial delivery of chemotherapeutic agents offers a new and exciting opportunity for the treatment of advanced intraocular retinoblastoma. It allows local delivery of relatively high doses of chemo agents while bypassing general blood circulation. For this reason we sought to revisit some of the FDA approved drugs for the treatment of retinoblastoma.

METHODS

High throughput screening (HTS) of 2,640 approved drugs and bioactive compounds resulted in the identification of cytotoxic agents with potent activity toward both the Y79 and RB355 human retinoblastoma cell lines. Subsequent profiling of the drug candidates was performed in a panel of ocular cancer cell lines. Induction of apoptosis in Y79 cells was assessed by immunofluorescence detection of activated Caspase-3. Therapeutic effect was evaluated in a xenograft model of retinoblastoma.

RESULTS

We have identified several FDA approved drugs with potent cytotoxic activity toward retinoblastoma cell lines in vitro. Among them were several cardiac glycosides, a class of cardenolides historically associated with the prevention and treatment of congestive heart failure. Caspase-3 activation studies provided an insight into the mechanism of action of cardenolides in retinoblastoma cells. When tested in a xenograft model of retinoblastoma, the cardenolide ouabain induced complete tumor regression in the treated mice.

CONCLUSIONS

We have identified cardenolides as a new class of antitumor agents for the treatment of retinoblastoma. We propose that members of this class of cardiotonic drugs could be repositioned for retinoblastoma if administered locally via direct intraarterial infusion.

INTRODUCTION

Retinoblastoma constitutes the most common primary ocular tumor of childhood, affecting approximately 5,000 to 8,000 children worldwide each year1..

Although the current survival rate associated with retinoblastoma is approximately 90% in developing countries2, in some cases successful treatment can often only be achieved by enucleation. Furthermore, current treatment modalities are limited by their toxicity.. Traditionally, tumor reduction is achieved by external beam radiotherapy or chemotherapy, prior to local treatment such as thermotherapy, cryotherapy radioactive plaque, brachytherapy1, 2.. Complications may arise from the use of radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy. The long term effects of external beam radiotherapy can include cataracts, radiation retinopathy, impaired vision, and temporal bone suppression2. Radiation also increases the incidence of second cancers in genetically primed patients, especially those under the age of one1.. Due to varying mechanisms of action, chemotherapy is synergistic and best used in combination with the stand three-drug regiment comprising carboplatin, etoposide, and vincristine2. Systemic chemotherapy-related side effects include cytopenia, neutropenia, gastrointestinal distress, and neurotoxicity for vincristine3–7. In addition, an increased risk for the development of second malignant neoplasms has been linked to the use of platinum-based drugs for the treatment of childhood malignancies, and secondary leukemias have been reported in retinoblastoma patients treated with etoposide8–10. In summary, the limitations of current therapeutic approaches employed to treat retinoblastoma, sometimes necessitating enucleation for effective treatment, underline the urgency of developing new and effective therapies.

There has been extensive research aimed at developing alternative agents for retinoblastoma that lack the risks associated with current chemotherapy. A series of studies have investigated the potential of calcitriol (vitamin D) and its derivatives as anti-proliferative agents11–14. However, mortality of treated animals due to hypercalcemia, remains an issue. Another example is Nutlin-3, a small-molecule inhibitor of Mdm2-p53 interaction15. Early preclinical studies have shown that Nutlin 3 induces apoptosis in two retinoblastoma cell lines16, 17. Nutlin-3 was also found to synergistically kill retinoblastoma cells in combination with topotecan, but had little effect when used alone16. Novel effective treatments for retinoblastoma have yet to emerge from those studies.

Intraarterial chemotherapy is an entirely new approach for the treatment of advanced intraocular retinoblastoma consisting in the selective ophthalmic artery infusion of chemotherapeutics18. In a first study with melphalan, drastic response to the treatment was observed with a locally administered dose of one tenth of the usual systemic dose of the chemotherapy agent18. Presumably, local intraarterial delivery of melphalan, by allowing to bypass the bloodstream, was responsible for the improved efficacy and diminished toxicity observed in this study. Intraarterial chemotherapy therefore constitutes an exciting new technique that opens the way to the use of previously neglected chemotherapeutic agents due to their high systemic toxicity for the treatment of retinoblastoma. For this reason we sought to revisit approved drugs and known bioactive compounds to identify potent agents for retinoblastoma to be administered by local intraarterial infusion.

In this paper, we describe the results of the first chemical screen specifically aimed at identifying alternative chemotherapeutic agents for retinoblastoma. We identified potent agents for retinoblastoma cells among a library of 2,640 mostly off-patent compounds consisting of marketed drugs, bioactive compounds in various therapeutic areas, toxic substances and natural products. Importantly, we found that the newly identified agents for retinoblastoma belong to well-described pharmacological classes, some agents currently being used in clinic. In this study, we characterize the potency of the newly identified drug candidates in different cellular models of retinoblastoma and we further evaluate cardenolides as a novel potent class of agents for retinoblastoma. We assess the in vivo efficacy of the cardenolide ouabain in a xenograft model of retinoblastoma, a drug historically used for the treatment of myocardial infarction. Based on our results, we propose that our strategy may lead to alternative potent treatments for retinoblastoma, with globe-conserving strategies in mind.

METHODS

Cell lines and tissue culture

The human retinoblastoma cell lines Y79 and WERI-Rb-1 were purchased from from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The human retinoblastoma cell line RB355 originally established by Dr. Brenda Gallie (University of Toronto) and the luciferase-expressing Y79LUC cell line were kindly provided by Dr. Michael Dyer (Saint Jude Children’s Research Hospital). The human uveal melanoma cell lines C918 and Mum2b originally established by Dr. Mary Hendrix (University of Iowa) were generously provided by Dr. Daniel Albert (University of Wisconsin). The cell lines Y79, WERI-Rb-1 and RB355 were grown in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 20% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA), 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin (Gemini Bio-Products, Sacramento, CA), 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 4.5 g/L glucose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cell line C918 was cultured in DMEM with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA), and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin. All cell lines were grown under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 95% air at 37°C under 85% humidity.

Cytotoxicity assay for screening in 1536-well microtiter plates

Library compounds were pre-plated in 1 µL of 1% DMSO (v/v) into 1536-well microtiter plates (#3893, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) using a TPS-384 Total Pipetting Solution (Apricot Designs. Monrovia, CA). Cells were added in 8 µL medium to the screening plates using a Flexdrop IV (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). After 72h incubation was added 1 µL Alamar Blue using Flexdrop. The cells were then incubated for another 24h, and the fluorescence intensity was read on the Amersham LEADseeker™ Multimodality Imaging System equipped with Cy3 excitation and excitation filters and FLINT epi-mirror. The signal inhibition induced by the compounds was expressed as a percentage compared to high and low controls located on the same plate, as defined as % Inhibition = (high control average – read value) / (high control average − low control average) × 100.

Cytotoxicity assay for dose response in 384-well microtiter plates

Dose response studies were performed in 384-well microtiter plates (#3712, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) according to the following protocol: cells were added in 45 µL medium to the screening plates using Flexdrop. After 72h incubation was added 5 µL Alamar Blue using Flexdrop. The cells were then incubated for another 24h, and the fluorescence intensity was read on LEADseeker™ Multimodality Imaging System as previously described. To calculate the IC50 for each compound toward each cell line, the dose response was assessed in duplicate and using 12 point doubling dilutions with 100 µM compound concentration as the upper limit. The dose response curve for each set of data was fitted separately, and the two IC50 values obtained were averaged. For compounds having an IC50 below 1 µM or 0.1 µM, the dose response study was repeated using dilutions starting at 10 µM or 1 µM for more accurate determination of the IC50 value.

Automation System & Screening Data Management

The assays were performed on a fully automated linear track robotic platform (CRS F3 Robot System, Thermo Electron, Canada) using several integrated peripherals for plate handling, liquid dispensing, and fluorescence detection. Screening data files from the Amersham LEADseeker™ Multimodality Imaging System were loaded into the HTS Core Screening Data Management System, a custom built suite of modules for compound registration, plating, data management, and powered by ChemAxon Cheminformatic tools (ChemAxon, Hungary).

Chemical Libraries, Automation System & Screening Data Management

The library used for the pilot screen combines 2,640 chemicals obtained commercially from Prestwick and MicroSource19–21. The MicroSource Library contains 2,000 biologically active and structurally diverse compounds from known drugs, experimental bioactives, and pure natural products. The library includes a reference collection of 160 synthetic and natural toxic substances (inhibitors of DNA/RNA synthesis, protein synthesis, cellular respiration, and membrane integrity), a collection of 80 compounds representing classical and experimental, pesticides, herbicides, and endocrine disruptors, a unique collection of 720 natural products and their derivatives. The collection includes simple and complex oxygen heterocycles, alkaloids, sequiterpenes, diterpenes, pentercyclic triterpenes, sterols, and many other diverse representatives. The Prestwick Chemical Library is a unique collection of 640 high purity chemical compounds, all off patent and carefully selected for structural diversity and broad spectrum, covering several therapeutic areas from neuropsychiatry to cardiology, immunology, anti-inflammatory, analgesia and more, with known safety, and bioavailability in humans. The library is constituted of 90% of marketed drugs and 10% bioactive alkaloids or related substances. A collection of naturally occuring derivatives of cardenolides was obtained from AnalytiCon Discovery22.

Apoptosis assay

Y79 cells seeded in culture medium in a 24-well plate were treated with either vincristine, etoposide, or ouabain at various concentrations in 1% DMSO (v/v) or with 1% DMSO (v/v) alone as a carrier control for 48h or 72h. After a wash in PBS, cells were fixed in solution in 4% (v/v) in PBS for 10 minutes. After a wash in PBS, cells for each condition were dried on a glass slide and washed once with water.

The immunofluorescence detection of cleaved Caspase-3 was performed at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Molecular Cytology Core Facility using a Discovery XT processor (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ). A rabbit polyclonal Cleaved Caspase 3 (Asp175) antibody (#9661L, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) was used at a concentration of 0.1 µg/ml. Cells were blocked for 30 minutes in 10% (v/v) normal goat serum, 2% (v/v) BSA in PBS prior to incubation with the primary antibody for 3 hours and subsequent 20 minutes incubation with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (#PK6101, Vector labs, Burlingame, CA) diluted 1:200. The detection was performed with Secondary Antibody Blocker, Blocker D, Streptavidin-HRP D (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ), followed by incubation with Tyramide-Alexa Fluor 488 (#T20922, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Nuclear staining was then performed by incubating the slides for 15 minutes in a 8 µM Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) solution in PBS and washing once with PBS. Automated fluorescence imaging of the green channel (activated Caspase-3) and blue channel (nuclei) was performed using an IN Cell Analyzer 1000 (GE Healthcare).

In vivo studies

Subcutaneous xenograft experiments were performed at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Antitumor Assessment Core Facility in adherence to the ARVO Animal Statement. Y79LUC cells (10E6) embedded in matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were injected subcutaneously in the right flank of 8-weeks old ICR/SCID male mice. Treatment started when the tumors reached approximately 250 mm3. The mice were randomized into three groups and two mice per group were treated with either 10% DMSO (v/v) (control group), 1.5 mg/kg ouabain or 15 mg/kg ouabain. Ouabain was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO) and its chemical identity was confirmed by mass spectrometry. Treatment was performed over a period of 19 days by continuous subcutaneous infusion using osmotic minipumps (#1007D, Alzet, Cupertino, CA), which provide a delivery rate of 0.5 µL per hour. Ouabain concentration in the minipump was 3.15 mg/mL for the 1.5 mg/kg group and 31.5 mg/mL for the 15 mg/kg group. The minipumps were inserted on the left flank, opposite to where the Y79 tumor was implanted and replaced every week.. Tumor size was measured externally two times a week with a caliper. Mouse weight was monitored as well as other signs of toxicity throughout the treatment period. Bioluminescent imaging of the tumors was performed once a week and prior to sacrifice as follows: mice were anesthetized by isofluorane inhalation and injected with D-luciferin at 50 mg/Kg (Xenogen) intraperitoneally; photonic emission was measured with the In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS 200, Xenogen) with a collection time of 5 seconds.

RESULTS

Identification of alternative cytotoxic agents for retinoblastoma among known drugs

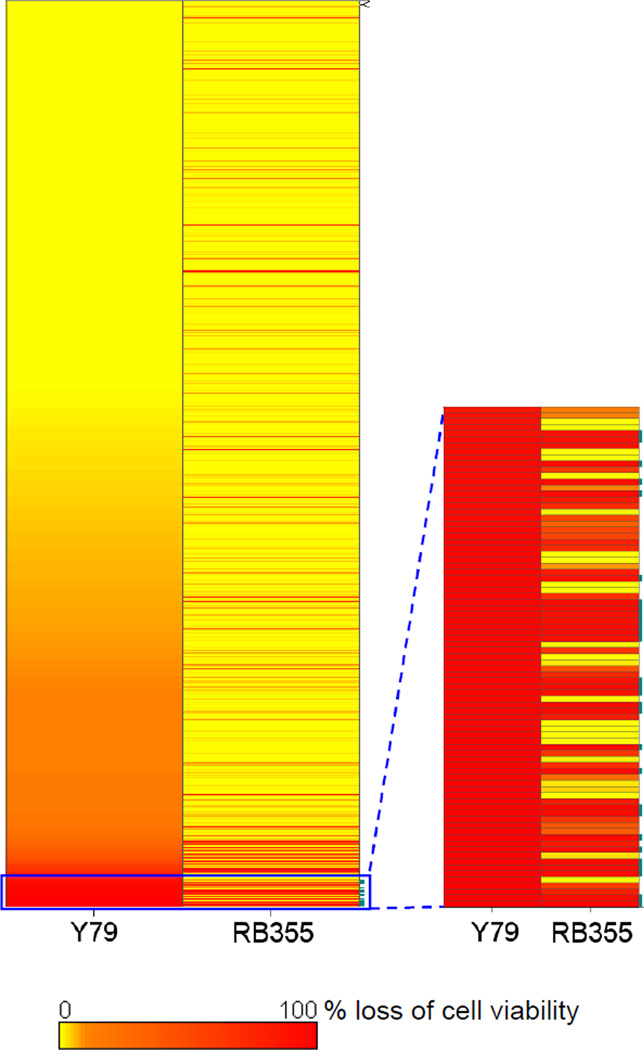

We aimed at identifying alternative cytotoxic agents for retinoblastoma among known drugs and bioactive agents. To meet this goal we screened a combined library of 2,640 commercially-obtained chemicals representing biologically active and structurally diverse compounds from known drugs, experimental bioactives, and pure natural products, mostly off-patent. We relied for the screen on the use of the well-described cytotoxicity assay based on the reduction of the dye resazurin and commercially sold as Alamar Blue23 due to its compatibility with the requirements of high-throughput screening24. In this assay, the fluorescence emitted by the living cells upon metabolism of Alamar Blue is proportional to the number of metabolically active cells. Hence, the cytotoxicity or the cytostaticity of a compound can be assessed relative to a control. Because we wanted to identify chemical scaffolds with broad activity for retinoblastoma as opposed to compounds only cytotoxic toward one specific retinoblastoma cell line, we adopted a strategy where we screened our combined drug library in parallel against two retinoblastoma cell lines. We chose to use the Y7925 and the RB35526 human cell lines as models of retinoblastoma because they are among the few well-established human retinoblastoma cell lines available and because we managed to optimize their growth in high density format (data not shown). Duplicate sets of the combined library of 2,640 compounds were tested at 10 µM consecutively the same day for each cell line. After statistical analysis of the duplicate sets of data to assess the reproducibility of the screen and to ensure the absence of systematic error, we calculated the average percentage inhibition for each compound based on high and low controls present on each plate as previously described27. When we compared the newly generated Y79 and RB355 data sets we found that a large population of the tested compounds was active only toward one of the two cell lines (Figure 1). This result validates our approach consisting in screening our combined drug library against two cell lines in parallel in order to select broad-acting compounds. We then compared in a scatter plot the percentage inhibition for each compound in both the Y79 and the RB355 data sets (Figure 2). While most tested compounds had no significant activity in either screen, or were active only in one screen, we focused on the population of compounds demonstrating greater than 95% inhibition in both screens in order to select as positives only those compounds that were likely to have broad activity for retinoblastoma. The chemical structures of the selected 11 positives at 95% inhibition threshold are depicted in Figure 3. We performed cytotoxicity profiling for these 11 positives against the human retinoblastoma cell lines Y79, RB355 and WERI-Rb-1, as well as against the uveal melanoma cell lines C918 and Mum2b. We found that all 11 selected positives had broad and potent cytotoxic activity against these five ocular cancer cell lines with calculated IC50s ranging from 40 nM to 27 µM (Table 1). All selected positives were cytotoxic toward at least three out of five cell lines while most of them (9 out of 11) were potent against all tested cell lines (Table 1). Interestingly, most of the selected positives could be grouped into two well-known pharmacological classes: ion pump effectors (five) and antimicrobial agents (four). Importantly, the four most potent compounds identified belonged to the pharmacological class of ion pump effectors. Among them was the drug digoxin, which is currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of cardiac arrythmia and for the prevention of heart failure.

Figure 1.

Overall comparative analysis of the Y79 and RB355 screens. The percentage loss of cell viability induced by each tested compound in both screens is represented as a heat map to identify those compounds potent toward both cell lines.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot comparative analysis of the Y79 and RB355 screens. The percentage loss of cell viability induced by each tested compound in both screens is represented as a scatter plot. The 29 positives at a threshold of 90% inhibition in both screens are highlighted in red, and the 19 cardenolides present in the library are highlighted in green to assess the proportion of cardenolides among all positives as well as their potency.

Figure 3.

Summary of the structures for the 11 positives selected at a threshold of 95% inhibition in both screens. (A) Cardenolides. (B) Non-cardenolides.

Table 1.

Summary of the 11 positives identified in the RB355/Y79 screening campaign. Positives belonging to the class of cardenolides are highlighted in orange. The calculated IC50s for each positive in the ocular cancer cell line cytotoxicity panel are detailed.

| IC50(µM) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound name | Chemical class | Pharmacological class | Therapeutic use | RB355 | Y79 | WERI-Rb-1 | C918 | Mum2b |

| Peruvoside | Cardenolide | Ion pump effector | Prevention of congestive heart failure | 0.32 | 0.57 | 5 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| Ouabain | Cardenolide | Ion pump effector | Prevention of congestive heart failure | 0.43 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| Neriifolin | Cardenolide | Ion pump effector | Cardiotonic | 0.44 | 0.47 | 2.1 | 0.23 | 0.04 |

| Digoxin | Cardenolide | Ion pump effector | Prevention of congestive heart failure, FDA approved | 1.8 | 2 | 5 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Digoxigenin | Cardenolide | Ion pump effector | 2.6 | 7 | 4.6 | 1.9 | 3.8 | |

| Propachlor | Chlorophenylacetamide | Herbicide | 2.1 | 2.1 | 7.1 | 6.2 | 9.8 | |

| Phenylmercuric acetate | Mercuric acetate | Antimicrobial | Fungicide | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 1.3 |

| PyrithIone zinc | Thioxopyridine | Antimicrobial | Treatment of dandruff, FDA approved | 2.3 | 7.1 | 2.1 | 7.1 | > 100 |

| Nigericin sodium | Polyether | Antimicrobial | 2.5 | > 100 | 27 | 18 | > 100 | |

| Primaquine | Methoxyquinoline | Antimicrobial | Antimalarial | 5.4 | 3.5 | 5.9 | 21 | 27 |

| Dihydrogambogic acid | Pyranoxantenone | 8.6 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 4 | ||

Cardenolides constitute a class of drugs with broad and potent cytotoxic activity toward ocular cancer cells

A structural analysis of the positives identified during the screen revealed that the five ion pump effectors that we previously characterized (Table 1): peruvoside, ouabain; neriifolin, digoxin and digoxigenin all share a common chemical scaffold (Figure 3A). This scaffold corresponds to the core structure of cardenolides. When we performed a structural search for compounds present in our combined library sharing the same scaffold, we identified 19 cardenolides. To our surprise, we found that all of them had induced greater than 75% inhibition toward at least one cell line during the screen, and that they constituted 10 out of the 29 positives at a threshold of 90% inhibition in both screens (Figure 2). In addition, 13 out of 19 cardenolides (68%) present in our combined library induced greater than 50% inhibition in both screens. This striking observation led us to focus on cardenolides as a new class of antiproliferative agents for retinoblastoma. To explore the structure activity relationship (SAR) within this chemical class we constituted a collection of 35 cardenolides and derivatives. We then assessed the dose response for each compound toward the ocular cancer cell lines Y79, RB355, WERI-Rb-1 and C918. The results of this structure-activity relationship (SAR) study are summarized in Figure 4. With 23 out of the 35 tested cardenolides (64%) having potent anti-proliferative properties toward at least two ocular cancer cell line tested (IC50<10 µM) (Figure 4A), we confirmed that cardenolides constitute a class of potent and broad-acting agents for retinoblastoma. The most potent compound among the 35 tested cardenolides (Derivative-1) had a calculated IC50 of 35 and 90 nM toward the cell lines C918 and RB355, respectively (Figure 4A and 4B). As we investigated the structure activity relationships underlying the potency of cardenolides in our panel of ocular cancer cells, we identified a clear trend among the 35 derivatives that we tested: the presence of a glycoside substituant on the 3-hydroxy group seemed to be important for potency. Indeed, 21 compounds among the 23 most potent derivatives tested (91%) had a glycoside moiety grafted to their 3-hydroxy group (Figure 4A). On the other hand, a significant proportion of the 12 less potent compounds (42%) did not have any glycoside moiety at this position (Figure 4A). This observation seems to indicate that the presence of such a glycoside substituant is beneficial to the broad and potent activity of cardenolides toward ocular cancer cells. Several cardenolides had potent activity across the entire panel of ocular cell lines tested, such as the drug ouabain, which has a long history in the treatment of heart failure28–30 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Structure-activity relationship study for a collection of 35 cardenolides in a panel of four ocular cancer cell lines. (A) Heat map and numerical summary of calculated IC50s for the 35 cardenolides in the ocular cancer cell line panel. The structure of identified chemical scaffolds is highlighted. (B) Representative dose response curves generated for Derivative-1 in the panel of ocular cancer cell lines. (C) Representative dose response curves generated for the drug ouabain in the panel of ocular cancer cell lines.

Compared potency of the cardenolide ouabain with known agents in cell models of retinoblastoma

We compared the potency of a representative of the cardenolide scaffold to known effective agents against retinoblastoma. Namely, we tested the dose response of the drug ouabain with the human retinoblastoma cell lines Y79 and RB355, and compared its potency to vincristine, etoposide, carboplatin, cisplatin, nutlin-3 and calcitriol. We chose ouabain as a representative of cardenolides because it had demonstrated broad and potent activity toward all the tested cell lines (Table 1, Figure 4A and 4B), and because of its long history as a cardiotonic drug. In our assay, ouabain was the most potent compound toward Y79 cells with an IC50 of 0.65 µM compared to 11 µM for etoposide and 78 µM for nutlin-3 (Figure 5A). The activity of vincristine toward Y79 cells reached a plateau at 50% inhibition, which prevented us from calculating an IC50 for this compound. Carboplatin, cisplatin and calcitriol did not demonstrate any significant activity toward Y79 cells below 100 µM in our assay. Oubain had a similar potency toward RB355 cells with an IC50 of 0.40 µM compared to 1.6 nM for vincristine, 0.97 µM for etoposide and 11 µM for nutlin-3 (Figure 5B). Cisplatin reached a maximum of 65% inhibition at 100 µM, and neither caboplatin or calcitriol had any significant activity below 100 µM. These results demonstrate that the in vitro potency of the cardenolide ouabain is comparable to or even greater than the most potent agents for retinoblastoma currently known. Interestingly, the fact that ouabain was equally potent toward these two cell lines suggests that its mechanism of action might be independent of DNA replication or cell division.

Figure 5.

Compared potency of the drug ouabain toward (A) Y79 cells and (B) RB355 cells with clinical agents and experimental drugs. (C) Summary of the calculated IC50s.

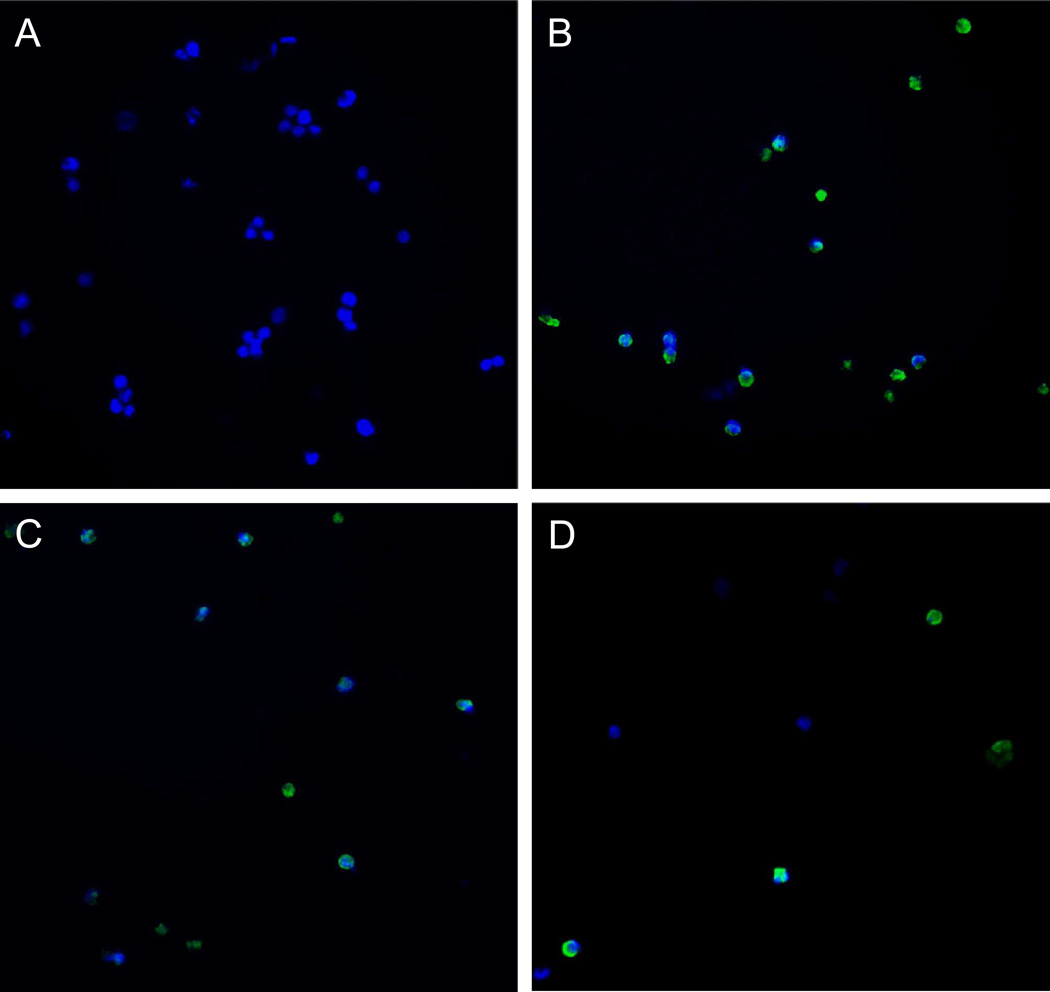

Compared effect of ouabain and clinical agents on apoptosis of Y79 cells

To determine whether the anti-proliferative effects of the drug ouabain was mediated by induction of apoptosis, we performed immunostaining of activated Caspase-3 in Y79 cells treated with cardenolides or known agents for retinoblastoma for 72h (green channel); treated cells were also stained with Hoechst to image the nuclei (blue channel) (Figure 6). The drug concentrations used in this experiment were previously determined according to a pilot study where treated Y79 cells were live-stained with the dye Yo-Pro, which stains apoptic cells31. Based on this study we identified 72h as the optimum incubation time and selected drug concentrations that maximized the number of apoptotic cells (data not shown). Baseline Caspase-3 activation was evaluated with control Y79 cells treated with 1% DMSO (v/v) (Figure 6A). We found that vincristine (Figure 6B) and etoposide (Figure 6C) induced significant apoptosis in Y79 cells compared to baseline levels, as previously described17, 32, 33. Interestingly, oubain in this experiment was used at a concentration of 0.5 µM compared to 100 µM for vincristine and 10 µM for etoposide because higher concentrations of ouabain erradicated Y79 cells in our pilot study with the dye Yo-Pro. At this lower concentration ouabain still induced significant apoptosis in our assay (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence detection of activated Caspase-3 in Y79 cells treated with (A) 1% DMSO (v/v); (B) 100 µM vincristine, 1% DMSO (v/v); (C) 10 µM etoposide, 1% DMSO (v/v); (D) 0.5 µM ouabain, 1% DMSO (v/v).

Assessment of the in vivo efficacy of ouabain in a xenograft model of retinoblastoma

We investigated the therapeutic effect of the drug ouabain in a mouse xenograft model of retinoblastoma. Three groups of two 8 weeks old ICR/SCID male mice bearing Y79 tumors implanted in the flank were treated with either vehicle only, 1.5 mg/kg ouabain or 15 mg/kg ouabain. Mice were continuously infused subcutaneously using an osmotic minipump delivery system, in order to mimic the local delivery that intraarterial chemotherapy allows to achieve. Evaluation of tumor burden by bioluminescent imaging shows that ouabain at 15 mg/kg rapidly induced a dramatic decrease in tumor size leading to complete tumor regression (as assessed by bioluminescence imaging) after 14 days of treatment (Figure 7). In comparison, tumors in the vehicle-treated control group continuously grew, necessitating to euthanize the animals at day 19. Quantification of tumor size confirmed this result: the average tumor size for the control group reached 1,000 mm3 at day 14 and kept growing while both animals treated with 15 mg/kg ouabain had their tumor nearly eradicated by day 14 (18 mm3 average size) (Figure 8A). At a lower dose of 1.5 mg/kg, ouabain seemed to reduce the tumor burden compared to the control group (Figure 8A). Throughout the treatment period, the average body weight of treated and control animals did not differ significantly, indicating that even at the high dose of 15 mg/kg ouabain did not induce any significant toxicity (Figure 8B).

Figure 7.

In vivo antitumor effect of the drug ouabain evaluated by bioluminescent imaging of tumor burden in a mouse xenograft model of retinoblastoma. Images for one representative mouse per group treated with either vehicle only (10% DMSO v/v) or 15 mg/kg ouabain, 10% DMSO v/v over 19 days are shown.

Figure 8.

(A) In vivo antitumor effect of the drug ouabain evaluated by tumor volume measurement in a mouse xenograft model of retinoblastoma. The average tumor volume per group over 19 days treatment is plotted. (B) Monitoring of animal weight. The average animal weight per group over 19 days treatment is plotted.

DISCUSSION

While effective treatments for retinoblastoma exist, they have important limitations. External beam radiation was once the standard therapy for retinoblastoma but has largely been abandoned due to risks of secondary malignancies34. Now replaced by the standard 3-drug regimen of carboplatin, vincristine and etoposide, concerns are emerging that the currently used chemotherapeutic agents for retinoblastoma may play a significant role in the occurence of secondary acute myelogenous leukemia7. Because of the limitations of currently available treatments, extensive research has aimed at discovering new agents for retinoblastoma. While preclinical studies were conducted on vitamin D analogs and nutlins, safety and efficacy for the use of these compounds in patients has yet to be demonstrated.

We present in this article an alternative strategy aiming at identifying novel agents for retinoblastoma among already approved drugs. We hypothesized that known drugs may have previously unreported antiproliferative properties for retinoblastoma, and could therefore potentially be repositioned as novel drugs for retinoblastoma. To test our hypothesis we constituted a combined library of 2,640 marketed drugs and bioactive compounds and developed a cytotoxicity assay amenable to high-throughput screening for the human retinoblastoma cell lines Y79 and RB355. A striking finding of our screening campaign was the discovery of the broad and potent antiproliferative activity toward retinoblastoma cells of the well-described chemical class of cardenolides. We confirmed this observation by establishing basic SAR for a series of 35 cardenolides and derivatives in a panel of four ocular cancer cell lines. We concluded from that study that a glycoside moiety grafted onto the cardenolide scaffold is important for broad activity. We identified a series of naturally occuring derivatives of cardenolides with broad and potent activity in our panel of ocular cancer cell lines, which are currently being further investigated. When comparing the in vitro antiproliferative properties of the drug ouabain to known or experimental agents for retinoblastoma, we reported that the potency of ouabain is comparable to agents currently used in clinic. The apparent discrepancy between the potency of vincristine and etoposide toward Y79 and RB355 cells could be explained by the difference in the doubling time of these cells: 45h for Y79 cells vs 24h for RB355 cells. Due to the mechanism of action of etoposide and vincristine relying on DNA replication and cell division respectively, these drugs most likely demonstrated a greater activity in our assay with RB355 cells because they divide faster than Y79 cells. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the drug ouabain induces apoptosis in Y79 human retinoblastoma cells at a dose of 0.5 µM. This observation is in agrement with previous studies showing that cardenolides induce apoptosis in various cell types30. Finally, when we assessed the therapeutic effect of ouabain in a xenograft model of retinoblastoma using a local delivery system, we observed a drastic response leading to complete tumor regression after 14 days of treatment. Even at the high dose of 15 mg/kg ouabain used in this study, no signs of toxicity were observed. Altogether, our results clearly validate our strategy, in that we have identified among other drugs the well-known class of cardenolides as novel agents for retinoblastoma.

Plant extracts from the genus Digitalis containing a mixture of cardenolides have been employed to treat congestive heart failure for centuries 30. Cardenolides such as the drug ouabain have been extensively used in clinic for 200 years as cardiotonics30. Cardenolides are still used in clinic today, including the FDA-approved drug digoxin for the treatment of cardiac arrythmia and for the prevention of congestive heart failure. The antiproliferative properties of cardenolides were initially investigated 40 years ago but the idea of using cardenolides to treat cancer was abandoned because of the narrow therapeutic index of this class of compounds30. It was later suggested that the concentration at which cardenolides induce apoptosis in cancer cells may be compatible with their therapeutic use30, 35. Clinical evidence seems to confirm this hypothesis, since breast cancer patients treated with digitalis were protected from aggressive disease and beneficiated from a lower cancer recurrence rate36, 37. Nevertheless, the potential for cardiovascular toxicity does exist when using this class of drugs systemically. For our purpose however, cardenolides constitute an exciting new class of agents for retinoblastoma because we have the opportunity to deliver them locally by selective ophthalmic artery infusion, as recently described in a phase I/II study18. In that study, direct infusion into the ophthalmic artery allowed the delivery of high concentrations of melphalan to the eye with markedly decreased toxicity compared to systemic administration. These promising results indicate that we could deliver high concentrations of cardenolides to the eye using intraarterial infusion without exposing the patient to potential cardiovascular toxicity.

Altogether our results demonstrate that cardenolides constitute an exciting new class of drug candidates for retinoblastoma. Among this class of drugs, digoxin which is approved by the FDA for the treatment of cardiac arrhytmia and to prevent congestive heart failure proved to be broadly potent across a panel of human retinoblastoma cell lines (Table 1). In light of the results of our study we therefore propose that the well-known cardiotonic drug digoxin could be repositioned for the treatment of retinoblastoma if administered locally via direct intraarterial infusion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the members of the MSKCC Antitumor Assessment Core Facility and the Molecular Cytology Core Facility for their contribution to this study. The authors are thankful to Dr. Mike Dyer (Saint Jude Children’s Research Hospital) for providing us with the cell lines RB355 and Y79LUC, and to Dr. Daniel Albert (University of Wisconsin) for the gift of the C918 and Mum2b cell lines. The authors are also grateful to Aida Bounama and other members of the HTS laboratory for their help during the course of this study. This study was sponsored in part by the Fund for Ophthalmic Knowledge. The HTS Core Facility is partially supported by the Mr. W.H. Goodwin and Mrs. A. Goodwin and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, The William Randolph Hearst Foundation, The Lillian S. Wells Foundation and The Experimental Therapeutics Center of MSKCC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson DH. Retinoblastoma in the 20th century: past success and future challenges the Weisenfeld lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2683–2691. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Potter P. Current treatment of retinoblastoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:331–336. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brichard B, De Bruycker JJ, De Potter P, Neven B, Vermylen C, Cornu G. Combined chemotherapy and local treatment in the management of intraocular retinoblastoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:411–415. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benz MS, Scott IU, Murray TG, Kramer D, Toledano S. Complications of systemic chemotherapy as treatment of retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:577–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck MN, Balmer A, Dessing C, Pica A, Munier F. First-line chemotherapy with local treatment can prevent external-beam irradiation and enucleation in low-stage intraocular retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2881–2887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.15.2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DL, Himelstein B, Shields CL, et al. Chemoreduction and local ophthalmic therapy for intraocular retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:12–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzuti AE, Dunkel IJ, Abramson DH. The adverse events of chemotherapy for retinoblastoma: what are they? Do we know? Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:862–865. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.6.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein G, Michaelis J, Spix C, et al. Second malignant neoplasms after treatment of childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:808–817. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00875-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura S, Sato T, Ueda H, Ueda K. Acute myeloblastic leukemia as a second malignancy in a patient with hereditary retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4182–4183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.21.4182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chantada G, Fandino A, Casak S, Manzitti J, Raslawski E, Schvartzman E. Treatment of overt extraocular retinoblastoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40:158–161. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert DM, Kumar A, Strugnell SA, et al. Effectiveness of vitamin D analogues in treating large tumors and during prolonged use in murine retinoblastoma models. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1357–1362. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.9.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert DM, Plum LA, Yang W, et al. Responsiveness of human retinoblastoma and neuroblastoma models to a non-calcemic 19-nor Vitamin D analog. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Audo I, Darjatmoko SR, Schlamp CL, et al. Vitamin D analogues increase p53, p21, and apoptosis in a xenograft model of human retinoblastoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4192–4199. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner N, Wagner KD, Schley G, Badiali L, Theres H, Scholz H. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells is associated with reciprocal changes of Bcl-2 and bax. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laurie NA, Donovan SL, Shih CS, et al. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature. 2006;444:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nature05194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elison JR, Cobrinik D, Claros N, Abramson DH, Lee TC. Small molecule inhibition of HDM2 leads to p53-mediated cell death in retinoblastoma cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1269–1275. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.9.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abramson DH, Dunkel IJ, Brodie SE, Kim JW, Gobin YP. A phase I/II study of direct intraarterial (ophthalmic artery) chemotherapy with melphalan for intraocular retinoblastoma initial results. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1398–1404. 1404, e1391. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prestwick Chemical, Inc., http://www.prestwickchemical.fr/

- 20.Microsource Discovery Systems, Inc., http://www.msdiscovery.com/

- 21.Desbordes SC, Placantonakis DG, Ciro A, et al. High-throughput screening assay for the identification of compounds regulating self-renewal and differentiation in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:602–612. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AnalytiCon Discovery GmbH, http://www.ac-discovery.com/

- 23.Ahmed SA, Gogal RM, Jr, Walsh JE. A new rapid and simple non-radioactive assay to monitor and determine the proliferation of lymphocytes: an alternative to [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. J Immunol Methods. 1994;170:211–224. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shum D, Radu C, Kim E, et al. A high density assay format for the detection of novel cytotoxic agents in large chemical libraries. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2008;23:931–945. doi: 10.1080/14756360701810082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reid TW, Albert DM, Rabson AS, et al. Characteristics of an established cell line of retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1974;53:347–360. doi: 10.1093/jnci/53.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fournier GA, Sang DN, Albert DM, Craft JL. Electron microscopy and HLA expression of a new cell line of retinoblastoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:690–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antczak C, Shum D, Escobar S, et al. High-throughput identification of inhibitors of human mitochondrial peptide deformylase. J Biomol Screen. 2007;12:521–535. doi: 10.1177/1087057107300463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoner W, Scheiner-Bobis G. Endogenous and exogenous cardiac glycosides: their roles in hypertension, salt metabolism, and cell growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C509–C536. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00098.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahimtoola SH, Tak T. The use of digitalis in heart failure. Curr Probl Cardiol. 1996;21:781–853. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2806(96)80001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman RA, Yang P, Pawlus AD, Block KI. Cardiac glycosides as novel cancer therapeutic agents. Mol Interv. 2008;8:36–49. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Idziorek T, Estaquier J, De Bels F, Ameisen JC. YOPRO-1 permits cytofluorometric analysis of programmed cell death (apoptosis) without interfering with cell viability. J Immunol Methods. 1995;185:249–258. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conway RM, Madigan MC, Billson FA, Penfold PL. Vincristine- and cisplatin-induced apoptosis in human retinoblastoma. Potentiation by sodium butyrate. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1741–1748. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giuliano M, Lauricella M, Vassallo E, Carabillo M, Vento R, Tesoriere G. Induction of apoptosis in human retinoblastoma cells by topoisomerase inhibitors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1300–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eng C, Li FP, Abramson DH, et al. Mortality from second tumors among long-term survivors of retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1121–1128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.14.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lopez-Lazaro M, Pastor N, Azrak SS, Ayuso MJ, Austin CA, Cortes F. Digitoxin inhibits the growth of cancer cell lines at concentrations commonly found in cardiac patients. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1642–1645. doi: 10.1021/np050226l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stenkvist B, Bengtsson E, Eriksson O, Holmquist J, Nordin B, Westman-Naeser S. Cardiac glycosides and breast cancer. Lancet. 1979;1:563. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90996-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stenkvist B. Is digitalis a therapy for breast carcinoma? Oncol Rep. 1999;6:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]