What are Streaming Potentials?

Streaming potentials occur in virtually every filtration process. For example, they occur when groundwater seeps through the soil, and of course they must also occur in filtering capillaries. Nevertheless, streaming potentials have attracted relatively little attention so far.

A streaming potential is generated whenever an ionic solution is forced though a charged filter. When the solute passes the filter, counterions will adhere to the filter surface in several layers. For example, a negatively charged filter perfused with NaCl solution will first attract a counterion layer of sodium ions, followed by a layer of chloride ions and so on until the order finally breaks down at some distance (usually 1 nm from the surface). Because of the increasing viscosity toward the filter surface, fluid moves at different speeds and finally comes to a halt within one of these layers of counterions (i.e., at the slip plane). The different spatial distribution of ions and speed of solute flux add up so that ions will pass the filter at different speeds (i.e., will be hindered differently; see Fig. 1). In most cases, filters or gels with a negative (anionic) electrostatic charge show a typical electrokinetic behavior: They will create an electrical field (a streaming potential), which is positive at the downstream side (cations pass the filter easier). For a more detailed review on the physics of streaming potentials, see Hausmann et al. (1) and Moeller and Tenten (2).

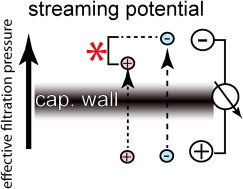

Figure 1.

Generation of streaming potentials. When an ionic solute is pushed though a charged filter (i.e., the capillary wall) by the effective filtration pressure, ions interact with the filter surface. As outlined in more detail in Hausmann et al. (1), ions pass the filter at different speeds, so that charge is separated only during the filtration process although the filter has virtually no electrical resistance.

Streaming Potentials and Capillary Permeability

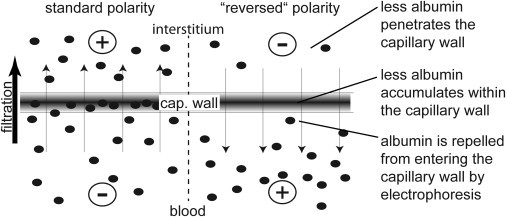

As already mentioned above, streaming potentials must also be generated across filtering capillaries. Because virtually all plasma proteins are negatively charged, the passage of plasma proteins across the capillary wall will be influenced by an additional novel force: electrophoresis. So far, this concept was dismissed because the walls of the filtering capillaries are negatively charged and therefore the polarity of the electrical field generated by filtration was predicted to be positive on the outside of the capillary and negative within the capillary lumen. Streaming potentials with this polarity would be counterproductive: They would increase the flux of plasma proteins into and across the capillary walls—which is in contrast to experimental observations (Fig. 2, left side).

Figure 2.

Consequences of a standard or reversed streaming potential across a filtering capillary. Plasma proteins (solid dots) are negatively charged. Because of continuous ongoing filtration, plasma proteins are driven across the capillary wall by convection and diffusion. (Left) When assuming a significant streaming potential, plasma proteins are in addition driven into and across the capillary wall by electrophoresis. This causes additional accumulation (clogging) within the capillary wall and increases the concentration of plasma proteins in the interstitial fluid (lymphatic fluid or primary urine). (Right) When assuming a reversed streaming potential, plasma proteins are repelled from entering or crossing the capillary wall by electrophoresis. The concentration of the plasma proteins is lower in the interstitium (lymphatic fluid or primary urine), consistent with experimental findings.

Reversed Streaming Potentials in Filtering Capillaries of Kidney Glomeruli

Recently, a streaming potential with a reverse polarity (positive in the capillary lumen, and negative downstream) was measured for the first time (to our knowledge) in vivo by direct micropuncture measurements in the common mudpuppy, an amphibian with larger capillaries (3). These measurements were performed in the glomerular capillaries of the kidney, which has the highest filtration pressures facilitating the detection of streaming potentials (of ∼−0.1 mV). A reversed streaming potential can explain multiple strange and so far unexplained phenomena: For example, why the filtering capillaries of the kidney never clog, although they produce 180 L of virtually protein-free ultrafiltrate: (Fig. 2, right side) Although streaming potentials with reversed polarity are physically possible by an electrokinetic phenomenon called overcharging (4–6), their detection in vivo spurred some controversy. The apparently false polarity of the streaming potential was the major argument brought forward against the proposed model of capillary filtration (i.e., the electrokinetic model) (7,8).

A Reversed Streaming Potential Across Bovine Lens Basement Membrane

As reported in this issue, Ferrell et al. (9) have used an endogenous basement membrane (from bovine lens basement membrane, LBM) for in vitro permeability studies to make two major observations:

-

1.

They rule out pressure-dependent changes in the intrinsic membrane properties—as it has been observed previously in other (more artificial) membrane preparations.

-

2.

The authors measure a streaming potential across the LBM, which has an opposite sign to what one would normally expect (i.e., the reversed polarity).

To our knowledge, this article of Ferrell et al. (9) is the first study to show convincingly that isolated basement membrane (resembling the basement membrane of capillaries) may generate a streaming potential with a reversed sign under the described experimental conditions. This is a little surprising because the endothelial glycocalyx was believed to be a more likely candidate—however, these results do not exclude this possibility. Of note, the magnitude of the observed streaming potential of isolated LBM (about two orders of magnitude less than in mudpuppy) is not necessarily of central importance. Filtering capillary walls are composed of several layers (endothelial cells plus basement membrane). In addition, the ionic composition, pH, and effective filtration pressure of the perfusate also modify the magnitude of the streaming potential. Finally, although a large body of indirect evidence already exists (summarized in Moeller and Tenten (2)), it still remains to be experimentally verified whether streaming potentials significantly influence the permeability of macromolecules (plasma proteins) by electrophoresis.

In summary, this study shows that reversed streaming potentials can be generated by extracellular matrix alone and is an independent confirmation that reversed streaming potentials are also generated in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant No. TP17 SFB/Transregio 57 of the German Federal and State Governments (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft), and a START grant by the Medical Faculty of the Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-Attribution Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.Hausmann R., Grepl M., Moeller M.J. The glomerular filtration barrier function: new concepts. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2012;21:441–449. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328354a28e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moeller M.J., Tenten V. Renal albumin filtration: alternative models to the standard physical barriers. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.58. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hausmann R., Kuppe C., Moeller M.J. Electrical forces determine glomerular permeability. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:2053–2058. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010030303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado A.V., Gonzalez-Caballero F., Lyklema J. Measurement and interpretation of electrokinetic phenomena. Pure Appl. Chem. 2005;77:1753–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyklema J. Overcharging, charge reversal: chemistry or physics? Colloids Surfaces Physicochem. Eng. Aspects. 2006;291:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyklema J. Quest for ion-ion correlations in electric double layers and overcharging phenomena. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;147–148:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harper S.J., Bates D.O. Glomerular filtration barrier and molecular segregation: guilty as charged? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:2009–2011. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010101071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson S.C., Blantz R.C. A new role for charge of the glomerular capillary membrane. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:2011–2013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010101089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrell N.J., Cameron K.O., Fissell W.H. Effects of pressure and electrical charge on macromolecular transport across bovine lens basement membrane. Biophys. J. 2013;104:1476–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]