Abstract

Purpose

Periodic limb movements (PLMs) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may present as overlapping conditions. This study investigated the occurrence of PLM during continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) titration, with the hypothesis that the presence of PLM during CPAP represented “unmasking” of a coexisting sleep disorder.

Methods

A total of 78 polysomnographic recordings in 39 OSA subjects with an hourly PLM index ≥5 during CPAP application were evaluated.

Results

Application of CPAP significantly improved sleep architecture without change in the PLM index when compared with baseline. The PLM indices and PLM arousal indices were linearly correlated during both nights (r = 0.553, P < 0.01; r = 0.548, P < 0.01, respectively). Eleven subjects with low PLM indices at baseline had greater changes in the PLM index as compared with the sample remainder (P = 0.004). Sixteen subjects with significantly lower PLM indices at baseline required optimal CPAP levels higher than the sample average of 8.2 cm H2O (P = 0.032). These subjects also showed significantly higher median apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) at baseline than the sample remainder (74.4 events per hour [range: 24.2–124.4 events per hour] vs. 22.7 events per hour [range: 8.6–77.4 events per hour], respectively, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that PLM seen during CPAP titration may be related to a concurrent sleep disorder because of “unmasking” in patients with treated OSA.

Keywords: Periodic limb movements (PLM), Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), Sleep disorders, Polysomnography

INTRODUCTION

Periodic limb movements represent a sleep-related condition characterized by repetitive limb movements. Although its prevalence is difficult to discern, researchers have found PLM to increase significantly with age (Coleman et al., 1981; Hening et al., 2007; Nicolas et al., 1999) while affecting genders undifferentially (AASM, 2007; Scofield et al., 2008). Periodic limb movements may be present in 80% to 90% of patients with restless legs syndrome (AASM, 2007). Periodic limb movement disorder is characterized by episodes of repetitive limb movements during sleep associated with clinical sleep disturbances, according to formal diagnosis criteria established by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (AASM, 2007). A large cross-sectional study found PLM disorder to affect 3.9% of a sample population of nearly 19,000 (Ohayon and Roth, 2002).

Periodic limb movements are more likely to occur in the lower extremities and consist of stereotypical limb movements lasting from 0.5 to 10 seconds reaching amplitude of at least 25% of baseline’s toe dorsiflexion during calibration, occurring in runs of ≥4 with an intermovement interval of 5 to 90 seconds during sleep. Movements may be associated with arousals from sleep or changes in sleep stage (AASM, 2007; Walters et al., 2007).

This condition has been associated with hypertension (Walters and Rye, 2009), restless legs syndrome (Allen et al., 2003; Barriere et al., 2005; Montplaisir et al., 1997), and reduced serum ferritin levels (AASM, 2007; Earley et al., 2008). The diagnosis of PLM during sleep is made based on surface electromyography (EMG) of the anterior tibialis during nocturnal polysomnography, which is judged to be the diagnostic gold standard (Flemons et al., 2003; Kushida et al., 2005).

It has been estimated that 25% of patients with PLM have a coexisting sleep disorder (Karatas, 2007). Of special interest is the relationship between PLM and OSA, as the clinical relevance of their coexistence remains unclear. Significant PLM has been found in 25% to 50% of patients with OSA in 2 studies (Al–Alawi et al., 2006; Chervin, 2001). A recent study (O’Brien et al., 2009) hypothesized that OSA would produce lower serum ferritin levels, which in turn would promote the development of PLM. Other researchers (Baran et al., 2003; Fry et al., 1989) have taken a specific interest in exploring the presence of PLM during the initiation of nasal CPAP. The most common treatment for OSA, CPAP provides a constant stream of pressurized air to splint open the upper airway and promotes unobstructed breathing during sleep. The mechanism by how CPAP implementation affects PLM has not yet been clearly demonstrated; however, the two main theories relate to either limb movements resulting from disturbances caused by the application of positive pressure or to CPAP’s “unmasking” of underlying coexistent PLM in those subjects (Baran et al., 2003; Fry et al., 1989; Iriarte et al., 2009).

Our study aimed to investigate the finding of PLM during first exposure to CPAP in a group of adult subjects who had undergone a full night baseline polysomnography for the diagnosis of OSA. We sought to expand on previous research to (1) better understand the relationship between PLM and OSA in subjects being treated with CPAP and (2) investigate the importance of PLM with associated arousals. For this preliminary study, we hypothesized that PLM is often “unmasked” during CPAP application.

METHODS

The subjects with a PLM index ≥5 per hour during a second night polysomnography for manual titration of CPAP were included in this study after approval by the institutional review board at Weill Cornell Medical College. Additional inclusion criteria were an AHI ≥5 events per hour on a full night baseline polysomnography and no previous exposure to CPAP. A total of 126 consecutive sleep studies of 63 subjects were examined for this study. Twenty-four subjects with the use of dopaminergic agents, gabapentin, or anti-depressants were excluded (Trenkwalder et al., 2008). For the remaining 39 subjects, polysomnographic information on sleep parameters, respiratory measurements, and oximetry were recorded and scored using standard clinical criteria (AASM, 2007). Scoring of all records was performed by an experienced registered polysomnographic technician, blinded to CPAP application. Respiratory events were scored according to the recommended rules by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM, 2007). Manual titration of CPAP was performed according to standard published criteria to eliminate all respiratory events (Kushida et al., 2008). Limb movements were calculated from EMG of the right and left anterior tibialis and required a minimum amplitude increase of 8 μV above the resting EMG voltage. The PLM index was calculated based on four or more stereotypical limb movements lasting between 0.5 and 10 seconds with an intermovement interval between 5 and 90 seconds during sleep. Periodic limb movements with associated electrocortical arousals were also calculated during sleep, generating the periodic limb movement arousal index. Arousals were defined as a 3- to 15-second increase in electroencephalogram activity occurring within <0.5 seconds of the PLM event. Arousals were scored if preceded by a period of at least 10 seconds of sleep (AASM, 2007). Leg movements occurring within 0.5 seconds of a respiratory event (apnea or hypopnea) were not counted (AASM, 2007).

Descriptive statistics for sleep characteristics (including mean, SD, median, and range, as appropriate) are presented for (1) all patients at baseline and during CPAP titration, (2) patients stratified by PLM index <5 vs. ≥5 (during CPAP titration), and (3) patients stratified by optimal level of CPAP as compared with the sample’s average of 8.2 cm H2O pressure. The paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used, as appropriate, to compare sleep characteristics between baseline and during CPAP titration. The 2-sample (unpaired) t-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used, as appropriate, to compare sleep characteristics between PLM index <5 vs. ≥5 and CPAP ≤8 vs. >8 (between-group analyses performed both at baseline and during CPAP titration). The Pearson correlation coefficient was also used to quantify the degree of linear correlation between PLM index and PLM arousal index at baseline and during CPAP titration. Multivariate analysis was not possible because of the small number of patients in some of the stratified classifications of interest and because of the high level of collinearity between many of the sleep characteristics. All P values are 2-sided with statistical significance evaluated at the 0.05 alpha level. Because approximately 14 comparisons involving the sleep characteristics were conducted (i.e., sleep characteristics compared between PLM index <5 vs. ≥5 and CPAP ≤8 vs. >8), the issue of multiplicity of outcomes may be a concern. Although all of the above comparisons were defined a priori for the primary outcomes of the study, readers may wish to evaluate statistical significance at a modified alpha level of 0.05/14 comparisons = 0.004. Under this alpha level, statistical significance is achieved when a P value for a given group comparison is <0.004. As a result, the overall and stratified univariate analyses presented are to be considered exploratory/hypothesis-generating when interpreted from this study. All analyses were performed in SPSS Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

A total of 39 subjects (27 men and 12 women) were included in this analysis. All the subjects had an initial polysomnographic diagnosis of OSA and, on a separate night, underwent an in-laboratory attended CPAP titration which revealed a PLM index ≥5 events per hour, meeting the study’s inclusion criteria. Their average age was 61.7 years (range 22–84) with a mean body mass index of 30.9 kg/m2 (SD ± 7.3). A total of 8 patients reported PLM symptoms at baseline during either wakefulness or sleep (20.5%). There were no significant differences in sleep study characteristics between groups of patients according to PLM symptoms, except for a lower mean percentage of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep at baseline (8.2% vs. 11.6%, P = 0.026). The polysomnographic characteristics of all the subjects at baseline and during CPAP titration are shown in Table 1. Overall, sleep architecture and sleep continuity showed marked improvement during first exposure to CPAP. As compared with baseline, the subjects on the CPAP night showed a significant increase in slow wave sleep (median = 1 minute [range: 0–29 minutes] vs. median = 0 minutes [range: 0–12 minutes], respectively, P = 0.051) and REM sleep (17.7 ± 5.7 vs. 10.9 ± 7.0 minutes, respectively, P < 0.0001), along with a significant decrease in stage 1 sleep (11.1 ± 6.2 vs. 21.9 ± 17.0 minutes, respectively, P = 0.001). Sleep efficiency was not significantly changed and remained relatively low at 74.8% (±15.7%) during CPAP application in this sample. Treatment with CPAP led to a reduction in median AHI compared with baseline (3 events per hour [range: 0–14 events per hour] vs. 38.2 events per hour [range: 8.6–124.4 events per hour], respectively, P < 0.001), demonstrating effective treatment of the underlying OSA. The average CPAP level needed to overcome obstructive respiratory events in this group was 8.2 cm H2O (range 5–16). None of these subjects presented a significant central component of respiratory disturbance during sleep.

TABLE 1.

Sleep Study Characteristics for All Subjects at Baseline and During CPAP Titration

| Baseline (n = 39) Mean ± SD Median (Min, Max) | CPAP (n = 39) Mean ± SD Median (Min, Max) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TST (min) | 302.13 ± 76.45 | 327.08 ± 86.26 | 0.127 |

| SE (% of TST) | 70.36 ± 14.89 | 74.77 ± 15.66 | 0.108 |

| Stage 1 (% of TST)* | 21.85 ± 16.99 | 11.08 ± 6.19 | 0.001 |

| Stage 2 (% of TST) | 64.90 ± 15.34 | 67.10 ± 8.02 | 0.368 |

| Stages SWS (% of TST) | 0 (0, 12.0) | 1 (0, 29.0) | 0.051‡ |

| Stage REM (% of TST)* | 10.85 ± 6.96 | 17.67 ± 5.66 | <0.001 |

| Sleep latency (min) | 12 (1.0, 278.0) | 11 (1.0, 88.0) | 0.812‡ |

| Latency to REM sleep (min)* | 154.92 ± 78.27 | 99.14 ± 55.98 | <0.001 |

| AHI (events/h)* | 38.2 (8.6, 124.4) | 3 (0, 14.0)† | <0.001‡ |

| Mean SaO2 sleep (%Hgb)* | 92.37 ± 2.13 | 94.21 ± 1.78 | <0.001 |

| SaO2 nadir sleep (%Hgb)* | 76.44 ± 8.31 | 84.51 ± 4.55 | <0.001 |

| PLMI (events/h) | 17.9 (0, 103.0) | 31.8 (5.0, 83.0) | 0.125‡ |

| PLMAI (events/h)* | 0.9 (0, 26.7) | 3.7 (0, 33.6) | <0.001‡ |

AHI, apnea–hypopnea index; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; PLMAI, periodic limb movement arousal index; PLMI, periodic limb movement index; REM, rapid eye movement; SaO2, oxyhemoglobin saturation; SE, sleep efficiency; SWS, slow wave sleep; TST, total sleep time.

Significance at P ≤ 0.05.

Residual AHI at optimal CPAP pressure (cm H2O).

P value from Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Eleven subjects (28%), including two with clinical symptoms of PLMs, met inclusion criteria based on the CPAP study but failed to demonstrate significant PLM on the baseline sleep study, as demonstrated in Table 2. These subjects showed a greater amount of REM sleep rebound during the CPAP night (P = 0.003), despite similar AHI (P = 0.569) and final CPAP pressure (P = 0.342) as compared with the remaining subjects (n = 28). A significant difference in the median ΔPLM indices was seen between these groups (P = 0.004), with a median increase in the PLM index of 17.0 events per hour (range: 5–71) in the group that did not meet diagnostic criteria for PLM at baseline. The median change in the arousal index associated with PLM was not significantly different between groups (P = 0.177). There was no difference in age between groups.

TABLE 2.

Sleep Study Characteristics for Groups Based on PLM Index at the Baseline Study

| PLM Index <5 Mean ± SD Median (Min, Max) (n = 11) | PLM index ≥ 5 Mean ± SD Median (Min, Max) (n = 28) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| TST (min) | 303.09 ± 110.09 | 301.75 ± 61.13 | 0.970 |

| SE (% of TST) | 66.64 ± 17.86 | 71.82 ± 13.63 | 0.399 |

| Stages NREM (% of TST) | 89.91 ± 8.53 | 88.75 ± 6.63 | 0.691 |

| Stage REM (% of TST) | 9.91 ± 8.44 | 11.21 ± 6.42 | 0.650 |

| AHI (events/h) | 60.6 (8.6, 124.4) | 38.0 (11.1, 79.8) | 0.469† |

| PLMI (events/h)* | 0 (0, 4.0) | 28.6 (5.0, 103.0) | <0.001† |

| PLMAI (events/h)* | 0 (0, 1.5) | 1.6 (0, 26.7) | <0.001† |

| CPAP | |||

| TST (min) | 349.82 ± 73.86 | 318.14 ± 90.32 | 0.271 |

| SE (% of TST) | 79.82 ± 9.81 | 72.79 ± 17.17 | 0.119 |

| Stages NREM (% of TST)* | 77.91 ± 5.32 | 84.14 ± 4.81 | 0.004 |

| Stage REM (% of TST)* | 22.09 ± 5.21 | 15.93 ± 4.89 | 0.003 |

| Residual AHI (events/h) | 3 (0, 14.0) | 2.1 (0, 4.0) | 0.569† |

| CPAP (cm H2O) | 9.00 ± 3.23 | 7.93 ± 2.64 | 0.342 |

| PLMI (events/h) | 17 (5.0, 71.0) | 32.9 (5.0, 83.0) | 0.346† |

| PLMAI (events/h) | 3.2 (0.5, 13.1) | 4.4 (0, 33.6) | 0.485† |

| Change between nights | |||

| Δ PLMI (CPAP—baseline)* | 17 (5.0, 71.0) | −3.2 (−91.0, 73.0) | 0.004† |

| Δ PLMAI (CPAP—baseline) | 3.2 (1.0, 13.0) | 1.2 (−8.0, 20.0) | 0.177† |

Significance at P ≤ 0.05.

P value from Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

AHI, apnea–hypopnea index; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; NREM, nonrapid eye movement; PLMAI, periodic limb movement arousal index; PLMI, periodic limb movement index; REM, rapid eye movement; SE, sleep efficiency; TST, total sleep time.

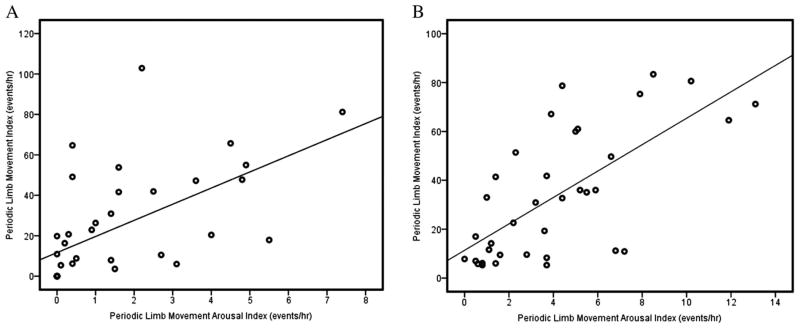

During each night, PLM indices and PLM arousal indices were positively correlated among all the subjects (baseline r = 0.553, P < 0.01; CPAP r = 0.548, P < 0.01), as shown in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Among the 39 subjects, periodic limb movement (PLM) index and PLM arousal index showed a significant positive correlation at baseline (A) and during continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) titration (B). Significance was determined at P < 0.01.

Periodic limb movement indices increased in 23 subjects (59%) during the CPAP night as compared to the baseline study by an average of 26.4 events per hour. The remaining 16 subjects (41%) showed a decrease in PLM index on the CPAP night by an average of 19.3 events per hour as compared with the baseline study. The average AHI and optimal CPAP levels were not statistically different between these 2 groups (P = 0.893 and P = 0.764, respectively). When specifically looking at the PLM arousal indices, they were higher during the CPAP night in 31 subjects (80%).

The study sample was also examined based on optimal level of CPAP relative to the sample average (8.2 cm H2O pressure) because of concerns about potential sleep fragmentation associated with higher CPAP pressures. A total of 16 subjects (41%) required CPAP levels >8 cm H2O, whereas 23 (59%) were optimally titrated at levels ≤8, as shown in Table 3. The groups differed in OSA severity, with the subjects requiring higher average CPAP levels having higher baseline AHI (median = 74.4 events per hour [range: 24.2–124.4 events per hour] vs. median = 22.7 events per hour [range: 8.6–77.4 events per hour], respectively, P < 0.001). The PLM indices at baseline were significantly lower in the group requiring higher CPAP pressure (median = 7.1 events per hour [range: 0–49 events per hour] vs. median = 26.3 events per hour [range: 0–103 events per hour], respectively, P = 0.032), and this group’s median PLM index during the CPAP night was thrice that of its average diagnostic (baseline) PLM index. During CPAP titration, those with optimal CPAP >8 cm H2O pressure showed larger improvements in sleep architecture-—including higher sleep efficiency (P = 0.03) and longer total sleep time (P = 0.016)—over those titrated to lower levels.

TABLE 3.

Sleep Study Characteristics for Groups Based on Optimal CPAP Requirement as Compared With the Group’s Average

| CPAP ≤ 8 Mean ± SD Median (Min, Max) (n = 23) | CPAP > 8 Mean ± SD Median (Min, Max) (n = 16) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| TST (min) | 295.43 ± 88.20 | 311.75 ± 56.84 | 0.487 |

| SE (% of TST) | 68.48 ± 16.43 | 73.06 ± 12.33 | 0.326 |

| Stages NREM (% of TST) | 88.87 ± 7.63 | 89.38 ± 6.53 | 0.826 |

| Stage REM (% of TST) | 11.13 ± 7.40 | 10.44 ± 6.48 | 0.759 |

| AHI (events/h)* | 22.7 (8.6, 77.4) | 74.4 (24.2, 124.4) | <0.001† |

| PLMI (events/h)* | 26.3 (0, 103.0) | 7.1 (0, 49.0) | 0.032† |

| PLMAI (events/h)* | 1.6 (0, 26.7) | 0.3 (0, 4.8) | 0.032† |

| CPAP | |||

| TST (min)* | 298.43 ± 71.12 | 368.25 ± 91.45 | 0.016 |

| SE (% of TST)* | 70.52 ± 16.71 | 80.88 ± 11.99 | 0.030 |

| Stages NREM (% of TST)* | 84.30 ± 4.90 | 79.63 ± 5.64 | 0.012 |

| Stage REM (% of TST)* | 15.74 ± 4.80 | 20.44 ± 5.79 | 0.012 |

| Residual AHI (events/h) | 2.1 (0, 4) | 3.0 (0, 14.0) | 0.404† |

| CPAP (cm H2O) | 6.30 ± 1.18 | 11.00 ± 2.03 | <0.001 |

| PLMI (events/h) | 36.0 (5.0, 83.0) | 21.0 (6.0, 79.0) | 0.489† |

| PLMAI (events/h)* | 5.1 (0, 33.6) | 2.7 (0.5, 7.9) | 0.029† |

| Change between nights | |||

| Δ PLMI (CPAP—baseline) | 3.6 (−91.0, 71.0) | 10.9 (−35.0, 73.0) | 0.301† |

| Δ PLMAI (CPAP—baseline) | 2.8 (−8.0, 20) | 1.1 (−1.0, 5.0) | 0.563† |

Denotes significance at P ≤ 0.05.

P value from Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

AHI, apnea–hypopnea index; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; NREM, nonrapid eye movement; PLMAI, periodic limb movement arousal index; PLMI, periodic limb movement index; REM, rapid eye movement; SE, sleep efficiency; TST, total sleep time.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the presence of significant PLM during CPAP application in a sample of subjects with OSA, and we found indication that PLM represent a coexisting sleep disturbance, unmasked by treatment of the underlying sleep apnea. In addition, several indicators of sleep architecture were markedly improved during the CPAP night as compared with the baseline study.

For several years, there has been a discussion regarding the true etiology of PLM that present during CPAP titration studies in patients with underlying OSA. There are conflicting theories (Fry et al., 1989): Some point to the “unmasking” of the PLM disorder, whereas others stress the causative effect of CPAP on PLM, arguing that the positive pressure exposure triggers repetitive limb movements in association with sleep fragmentation and bodily discomfort. In this sample, sleep efficiency was not significantly changed as compared with baseline, which may be attributed to the presence of underlying PLM in these subjects, instead CPAP use. Researchers (Iriarte et al., 2009) have shown that subjects with PLM exhibit disrupted sleep architecture, sometimes even more so than subjects with OSA, as demonstrated by lower sleep efficiency and total sleep time. In our study, total sleep time and sleep efficiency failed to significantly improve during CPAP application in these subjects with PLM indices ≥5 events per hour. Still, the effect of CPAP as a trigger for PLM is doubtful. Our study revealed that the 28% of the subjects with the largest increase in PLM during CPAP application had more pronounced REM sleep rebound, likely reflecting improved sleep architecture because of resolution of respiratory events and providing no evidence to support that residual respiratory changes may be causative factor for PLM in that group.

In analyzing the subjects according to CPAP requirements, there was no major change in PLM frequency between nights in the group requiring CPAP levels lower than the sample’s average. This finding corroborated previous results (Carelli et al., 1999), which demonstrated a relatively constant periodicity of PLM before and after CPAP treatment. Moreover, these results support the “unmasking” theory, and add to the findings of increased PLM indices during CPAP titration in subjects with moderate-to-severe OSA (Baran et al., 2003). Building on previous research (Briellmann et al., 1997), the group of Baran et al. (2003) proposed the notion that PLM may be either spontaneous (“unmasked” during CPAP) or induced (brought on by respiratory effort related arousals). Spontaneous PLM often appear during CPAP titration in subjects with high AHI and likely signify a true coexisting PLM disorder, as suggested by our study findings. Induced PLM may result from residual respiratory events not fully treated by CPAP. In our study, by using a strict methodology to CPAP titration, it is not likely that the PLM events were related to respiratory events; however, the lack of scoring of more subtle events such as respiratory event related arousals adds an important limitation when interpreting the data. Evaluating the periodicity of PLM may be a useful strategy to differentiate between respiratory-related PLM and pure neurological PLM (Nicolas et al., 1999).

A first night effect of CPAP application on sleep architecture has also been described by other researchers (Kaplan et al., 2007; Lorenzo and Barbanoj, 2002); however, it should not have caused the differential effect of PLM indices seen between CPAP groups in our study. The literature also cites evidence of increased PLM arousal indices over continued CPAP use, as the arousal threshold is lowered after an initial sleep rebound and the brain is more susceptible to register EMG activation, further reinforcing the “unmasking” theory (Fry et al., 1989; Kaplan et al., 2007).

Researchers (Fry et al., 1989) found a significant increase in electrocortical arousals associated with PLM after treatment with CPAP. The literature has shown that PLM are associated with corresponding changes in traditional and spectral electroencephalogram analyzes (Ferri and Zucconi, 2008; Walters et al., 2007). Currently, there remains some disagreement in scoring of PLM with associated arousals, particularly as it relates to the duration of the arousal and timing in relation to PLM (Allena et al., 2009; Bonnet et al., 2007; Sforza et al., 2003; Walters et al., 2007). In our study, CPAP was not titrated to eliminate PLM events, and it showed that the PLM index and the PLM arousal index were closely correlated for each night.

This preliminary study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged besides its small sample size, including the absence of a clinical component for the verification of symptoms pertaining to limb movements during wakefulness or sleep, and the lack of a prospective evaluation of the persistence of limb movements over time. Therefore, our results should be viewed as exploratory at this time.

The perception that CPAP may fragment sleep and trigger PLM was not supported by this study, which leads us to conclude that PLM, when seen during CPAP polysomnography, are likely related to “unmasking” after removal of the obstructive respiratory events. In addition, given that nearly 80% of our sample showed an increase in PLM arousal indices during the CPAP titration, our data support previous research (Bonnet et al., 2007; Exar and Collop, 2001; Fry et al., 1989), which suggests that PLM with associated arousals deserve further evaluation, Arousals associated with PLM may contribute to clinical symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness and worse quality of life, while possibly increasing the chances for the development of adverse health effects because of sleep fragmentation and increased sympathetic tone.

In conclusion, this study underscores the importance of recognizing PLM as a concurrent sleep disorder in several subjects with OSA presenting for CPAP titration. Further prospective studies are recommended to address the long-term effects of CPAP on the “unmasking” of PLM after treatment of sleep apnea. In a clinical environment, the potential for an additive effect on cardiovascular risk because of coexisting PLM in patients with OSA further highlights the clinical relevance of this problem.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the entire staff of the Center for Sleep Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College for their assistance in this project. They also wish to thank Barnard College professors Dr. John Glendinning and Dr. Peter Balsam for their guidance and support throughout this project. Dr. Christos was partially supported by the following grant: Clinical Translational Science Center (UL1-RR024996).

Footnotes

There is no financial disclosure from the participating authors.

The abstract was presented at the 24th Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies, LLC in San Antonio, TX, on June 7, 2010.

References

- AASM. American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Alawi A, Mulgrew A, Tench E, Ryan CF. Prevalence, risk factors and impact on daytime sleepiness and hypertension of periodic leg movements with arousals in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101–119. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allena M, Campus C, Morrone E, et al. Periodic limb movements both in non-REM and REM sleep: relationships between cerebral and autonomic activities. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:1282–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baran AS, Richert AC, Douglass AB, et al. Change in periodic limb movement index during treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep. 2003;26:717–720. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriere G, Cazalets JR, Bioulac B, et al. The restless legs syndrome. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;77:139–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet MH, Doghramji K, Roehrs T, et al. The scoring of arousal in sleep: reliability, validity, and alternatives. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:133–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briellmann RS, Mathis J, Bassetti C, et al. Patterns of muscle activity in legs in sleep apnea patients before and during nCPAP therapy. Eur Neurol. 1997;38:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000113173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli G, Krieger J, Calvi-Gries F, Macher JP. Periodic limb movements and obstructive sleep apneas before and after continuous positive airway pressure treatment. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:211–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervin RD. Periodic leg movements and sleepiness in patients evaluated for sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1454–1458. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.8.2011062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RM, Miles LE, Guilleminault CC, et al. Sleep–wake disorders in the elderly: polysomnographic analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1981;29:289–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1981.tb01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley CJ, Ponnuru P, Wang X, et al. Altered iron metabolism in lymphocytes from subjects with restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2008;31:847–852. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.6.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exar EN, Collop NA. The association of upper airway resistance with periodic limb movements. Sleep. 2001;24:188–192. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri R, Zucconi M. Heart rate and spectral EEG changes accompanying periodic and isolated leg movements during sleep. Sleep. 2008;31:16–17. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.1.16. discussion 18–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemons WW, Littner MR, Rowley JA, et al. Home diagnosis of sleep apnea: a systematic review of the literature. An evidence review cosponsored by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the American Thoracic Society. Chest. 2003;124:1543–1579. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry JM, DiPhillipo MA, Pressman MR. Periodic leg movements in sleep following treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 1989;96:89–91. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hening W, Allen RP, Tenzer P, Winkelman JW. Restless legs syndrome: demographics, presentation, and differential diagnosis. Geriatrics. 2007;62:26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte J, Murie-Fernandez M, Toledo E, et al. Sleep structure in patients with periodic limb movements and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;26:267–271. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3181aed01e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JL, Chung SA, Fargher T, Shapiro CM. The effect of one versus two nights of in-laboratory continuous positive airway pressure titration on continuous positive airway pressure compliance. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5:117–129. doi: 10.1080/15402000701190614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatas M. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements during sleep: diagnosis and treatment. Neurologist. 2007;13:294–301. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181422589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushida CA, Chediak A, Berry RB, et al. Clinical guidelines for the manual titration of positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Positive airway pressure titration taskforce of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:157–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushida CA, Littner MR, Morgenthaler T, et al. Practice parameters for the indications for polysomnography and related procedures: an update for 2005. Sleep. 2005;28:499–521. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo JL, Barbanoj MJ. Variability of sleep parameters across multiple laboratory sessions in healthy young subjects: the “very first night effect”. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:409–413. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, et al. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: a study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord. 1997;12:61–65. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas A, Michaud M, Lavigne G, Montplaisir J. The influence of sex, age and sleep/wake state on characteristics of periodic leg movements in restless legs syndrome patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1168–1174. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien LM, Koo J, Fan L, et al. Iron stores, periodic leg movements, and sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;05:525–531. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scofield H, Roth T, Drake C. Periodic limb movements during sleep: population prevalence, clinical correlates, and racial differences. Sleep. 2008;31:1221–1227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sforza E, Jouny C, Ibanez V. Time course of arousal response during periodic leg movements in patients with periodic leg movements and restless legs syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:1116–1124. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenkwalder C, Hening WA, Montagna P, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice. Mov Disord. 2008;23:2267–2302. doi: 10.1002/mds.22254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters AS, Lavigne G, Hening W, et al. The scoring of movements in sleep. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:155–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters AS, Rye DB. Review of the relationship of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep to hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. Sleep. 2009;32:589–597. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.5.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]