Abstract

Hypoxia is a dynamic feature of the tumor microenvironment that contributes to drug resistance and cancer progression. We previously showed that components of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) elicited by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, are also activated by hypoxia in vitro and in animal and human patient tumors. Here, we report that ER stressors, such as thapsigargin or the clinically used proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, exhibit significantly higher cytotoxicity towards hypoxic compared to normoxic tumor cells, which is accompanied by enhanced activation of UPR effectors in vitro and UPR reporter activity in vivo. Treatment of cells with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide, which relieves ER load, ameliorated this enhanced cytotoxicity, indicating that the increased cytotoxicity is ER stress-dependent. The mode of cell death was cell-type dependent, since DLD1 colorectal carcinoma cells exhibited enhanced apoptosis, whereas in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells, activated autophagy blocked apoptosis and eventually led to necrosis. Pharmacologic or genetic ablation of autophagy increased the levels of apoptosis. These results demonstrate that hypoxic tumor cells, which are generally more resistant to genotoxic agents, are hypersensitive to proteasome inhibitors and suggest that combining bortezomib with therapies that target the normoxic fraction of human tumors can lead to more effective tumor control.

Keywords: Hypoxia, UPR, proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, autophagy

Introduction

Tumor hypoxia, or fluctuating regions of low oxygen tension, is an important feature of the tumor microenvironment that is known to promote cancer progression, decreased response to therapy and poor overall patient survival(1). Hypoxic tumor cells activate hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent and HIF-independent survival mechanisms that promote adaptation to low oxygen availability(2, 3). Previous work from our lab and others demonstrated that cells respond to hypoxic stress by phosphorylating the translation initiation factor eIF2α thereby reducing global translation rates(4–7). The eIF2α phosphorylation at serine 51 (Ser51) under hypoxia is dependent upon the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) kinase PERK(4, 7) and was found to occur independently of HIF-1α status, as HIF-1α−/− MEFs exhibited similar levels of eIF2α phosphorylation as HIF-1α+/+ MEFs(4).

This rapid and reversible inhibition of protein synthesis under hypoxia not only leads to energy conservation by reducing the quantity of proteins being made that require folding within the ER(8) but also upregulates gene products involved in the recovery from ER stress, such as protein chaperones and others promoting amino acid sufficiency and redox homeostasis (6, 9). Some of the effects of PERK activation are mediated by ATF4, a transcription factor translationally upregulated by ER stress in an eIF2α phosphorylation-dependent manner(8). This PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 pathway, is one arm of a larger, coordinated ER stress program known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). In addition to PERK, UPR signaling is mediated by two other ER transmembrane proteins: IRE1 and ATF6. Upon ER stress, active IRE1 processes XBP-1 mRNA, removing a 26-nucleotide intron to generate a spliced XBP-1 mRNA encoding the functional XBP-1 transcription factor(10, 11). Together, these pathways coordinately upregulate transcription of UPR target genes, such as the ER chaperone BiP/GFP78 and proteins involved in ER-associated degradation (ERAD), which aid in restoring ER homeostasis. However, IRE1 and another UPR target, CHOP, are also involved in ER stress-induced apoptosis(12). Thus the UPR, while activated as a pro-survival response under moderate or intermittent ER stress, can also lead to cell death under conditions of acute or chronic stress(8).

The ERAD system shuttles misfolded proteins from the ER lumen to the cytosol where they become ubiquitinated and degraded by the 26S proteasome (13). Bortezomib (PS-341; Velcade™), a highly selective and reversible inhibitor of the 26S proteasome approved for clinical use against multiple myeloma, is in clinical trials as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapeutics against other solid tumor malignancies(14). The mechanisms involved in its anti-cancer activity are still being elucidated, but evidence suggests that it is in part due to the altered degradation of key regulatory proteins such as IκB(15). More recently, bortezomib was shown to induce ER stress and ER-dependent apoptosis by blocking the ERAD system thereby promoting the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER that induce proteotoxicity and cell death(13, 16–19).

Several studies have established that the UPR is activated in human tumors and that disruption of the UPR inhibits tumor growth. GRP78/BiP, a major ER chaperone protein that negatively regulates UPR activation, is upregulated in many human tumors, confers drug resistance, promotes angiogenesis and correlates with malignancy(20–22). Results from our lab showed cells with a compromised PERK-eIF2α pathway are more sensitive to hypoxic stress in vitro and grow smaller tumors in vivo, suggesting this pathway is important for hypoxia tolerance in growing tumors(9). Moreover, ATF4 levels are increased by hypoxia in a HIF-independent manner and are upregulated near necrotic areas in human tumors(9, 23, 24). Romero-Ramirez et al. demonstrated that the IRE1-XBP-1 pathway is also critical for surviving hypoxic stress in vitro and more importantly, for optimal tumor growth in vivo(25). While one attractive approach to target the UPR in tumors is to develop inhibitors against its critical effectors (e.g., against PERK or IRE1), we postulated that another approach could take advantage of its pro-death activity under extreme or prolonged stress.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

DLD1 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells, HeLa human cervical adenocarcinoma cells (ATCC), HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells and PERK mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were maintained in DMEM media. HT29 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (ATCC) were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium. All media were supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, 10% FBS and L-glutamine (2mM). Bortezomib (Velcade; PS-341; Millennium Pharmaceuticals), thapsigargin, staurosporine, MG132, cycloheximide, chloroquine and etoposide (Sigma) were dissolved in DMSO and stored at −20°C.

Hypoxia Treatments

Cells were placed in an InVivo 400 Hypoxia Workstation (Biotrace, Inc.) for the time(s) indicated. Cells were sustained as indicated at severe hypoxia (<0.2% O2; 5% CO2; 10% H2) or moderate hypoxia (1% O2; 5% CO2). Oxygen concentrations were verified using the OxyLite pO2 E-series probe (Oxford Optronix).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (Koumenis et al, 2002) (4). Primary antibodies used are detailed in the Supplemental Material.

Nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation

Isolating nuclear protein was performed as described in the Supporting Information. Nuclear protein (40–70μg) was analyzed by immunoblotting for ATF4, CHOP and XBP-1.

Detecting XBP-1 splicing by RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was generated from 2μg RNA using AMV-reverse transcriptase (Promega). XBP-1 was amplified by PCR as described in the Supplemental Material.

Bioluminescence experiments

HT1080 cells or PERK MEFs stably-expressing the ATF4-luciferase construct were treated as indicated, washed with 1xPBS and lysed (30min, 24°C) in 400μl 1x Reporter Lysis Buffer (RLB; Promega). Lysates (100μl) were mixed with an equal volume of luciferase substrate (Promega) and assayed using a luminometer. CB17-SCID mice were injected SQ with 0.5–2×106 HT1080-CMV-luc cells on the left flank and HT1080-ATF4-luc cells on the right flank and allowed to grow for 2–3 weeks. Mice were then injected i.p. with vehicle or bortezomib (1mg/kg) and 8h later optical bioluminescence imaging was performed using the IVIS-100 system (Xenogen). Mice were imaged for 1–4 minutes per acquisition scan. Signal intensities were analyzed using Living Image software (Xenogen). Quantification based on 5 untreated mice and 4 treated mice in two experiments. Average tumor volume was 1808 ± 321 mm3 (HT1080-CMV-luc) and 1311 ± 293 mm3 (HT1080-ATF4-luc).

siRNA transfections

Beclin1 or non-targeting negative control siRNAs (50nM; Dharmacon) were transfected into HeLa cells (1×106cells/plate) using siPORT NeoFX (Ambion). 30h post-transfection the cells were treated as indicated, harvested for immunoblots or plated for clonogenic survival assays.

Clonogenic survival assays

Cells were plated in 6-cm diameter dishes at three different densities (100, 300, 1000 cells/plate) and were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions (0–1% O2) before treatment with vehicle (DMSO) or different concentrations of thapsigargin, etoposide, MG132 or bortezomib for the indicated times. For the cycloheximide experiments, cycloheximide (1μg/ml) was added at the same time as the various doses of bortezomib. Then the drug/media was removed, cells were rinsed with 1X PBS and allowed to incubate in fresh media under normal conditions for 7–14 days. Platings were performed in triplicate. After incubation, cells were fixed with 10% methanol-10% acetic acid and stained with a 0.4% solution of crystal violet. Colonies with more than 50 cells were counted. Plating efficiencies were determined for each treatment and normalized to controls. Error bars represent standard error (s.e.).

Analysis of autophagy and necrosis

Acridine orange staining and electron microscopy for analysis of autophagy and LDH detection assay and HMGB1 isolation for analysis of necrosis were performed as described in the Supplemental Material.

GFP-LC3 transfections

HeLa cells were transfected with 0.4 μg pcDNA3.1/GFP-LC3 plasmid using Lipofectamine LTX and PLUS reagent (Invitrogen) and 24h-post transfection cells were treated for 4h with DMSO, bortezomib or chloroquine under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. The cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (1:1000, 5min, RT), rinsed with 1xPBS, fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (15min, RT) and mounted on glass slides with hardening gel. Images were obtained using a Nikon epifluorescence microscope at 60× magnification.

Results

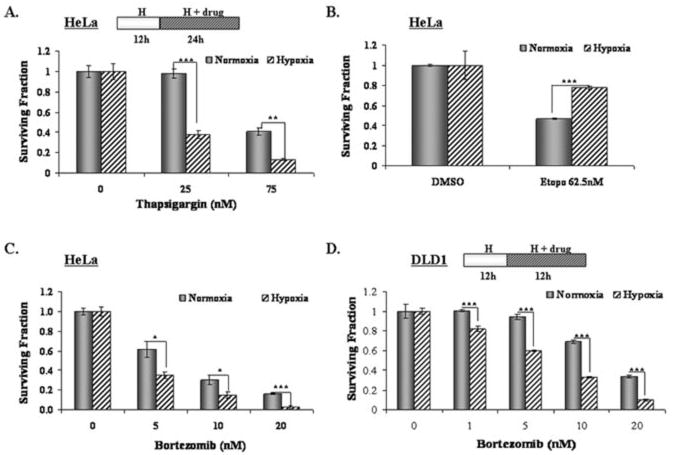

Hypoxia sensitizes human tumor cells to the ER stressor thapsigargin

Tumor hypoxia increases cellular resistance to various chemotherapeutic agents (1). We hypothesized that hypoxic cells would be hypersensitive to agents that induce ER stress. To test this, we compared the cytotoxic effects of thapsigargin, a pharmacologic inhibitor of the SERCA pump, on normoxic and hypoxic tumor cells. As shown in Figure 1A, HeLa cells pre-exposed to hypoxia (<0.2% O2) were significantly more sensitive to low doses of thapsigargin compared to normoxic cells. In contrast, etoposide, a genotoxic chemotherapeutic agent was less effective in killing tumor cells under hypoxia (Fig. 1B). The preferential sensitivity to thapsigargin was also evident under more moderate hypoxic conditions (1% O2) (Fig. S1A). This response was not cell-type specific as hypoxic HT29 colorectal cells were also more sensitive to thapsigargin compared to their normoxic counterparts (data not shown). These results suggested that hypoxic tumor cells are preferentially sensitive to pharmacologic ER stressors.

Figure 1. Hypoxic tumor cells are sensitive to ER stressors.

Tumor cells were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 12h before treatment with the indicated agents for 12h (DLD1) or 24h (HeLa). Error bars represent s.e. values. (A) Clonogenic survival of HeLa cells treated with thapsigargin. ** p = 0.001; *** p = 0.0002. (B) Hypoxic HeLa cells are more resistant to etoposide. *** p < 0.001. (C) Clonogenic survival of HeLa cells treated with bortezomib. * p ≤ 0.03; *** p < 0.001. (D) Hypoxic DLD1 cells are also more sensitive to bortezomib than normoxic cells. *** p < 0.001.

Hypoxic tumor cells are preferentially sensitive to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib

While a potent UPR activator, thapsigargin has a narrow therapeutic window since it is also highly toxic towards normal, untransformed cells(26). Therefore, its clinical potential is limited. Conversely, the dipeptide boronic acid proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (PS-341; Velcade™) which was shown to induce ER stress in human tumor cells, is in clinical use(14, 16–19). While work by Veschini et al. reported that endothelial cells (HUVECs) are sensitive to bortezomib(27), its toxicity towards hypoxic tumor cells has not been examined. Low nM concentrations of bortezomib induced the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins under both normoxia and hypoxia, indicating that bortezomib inhibited 26S proteasome activity to the same extent (Fig. S1C). Similar to the results obtained with thapsigargin, hypoxic HeLa cells were significantly more sensitive to bortezomib compared to normoxic cells (Fig. 1C, Fig. S1B). A similar response was seen in DLD1 colorectal carcinoma cells treated with bortezomib (Fig. 1D, Fig. S1B). Moreover, hypoxic DLD1 cells were also hypersensitive to another proteasome inhibitor, MG132, compared to normoxic cells (Fig. S1D), indicating this increased sensitivity was not due to non-specific effects of bortezomib. These results demonstrate that hypoxic tumor cells are more sensitive to proteasome inhibition and suggest that the enhanced cytotoxicity may be due to overactivation of ER stress-dependent pathways.

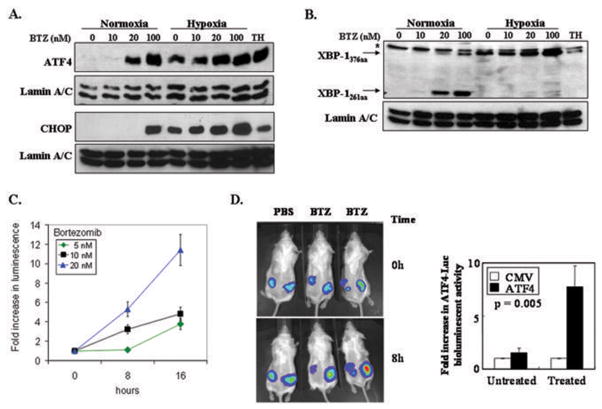

UPR signaling is enhanced in hypoxic tumor cells treated with bortezomib

Although it has been reported that bortezomib can induce the UPR in solid tumor cell lines(17–19), other studies have shown that it compromised UPR activation in myeloma cells(16). To assess the effect of hypoxia and bortezomib on the UPR, we analyzed the induction of UPR targets ATF4, CHOP and XBP-1. Under normoxic conditions, bortezomib induced eIF2α phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S2A). Hypoxia alone induced eIF2α phosphorylation and although this phosphorylation was not enhanced with bortezomib, the levels of the downstream targets ATF4 and CHOP, which accumulate in an eIF2α phosphorylation-dependent manner, were enhanced with the combined treatment (Fig. 2A). Thapsigargin treatment also induced a robust accumulation of ATF4 and CHOP. A higher concentration of Thapsigargin was used compared to treat in the clonogenic assay experiments (Fig. 1), since the duration of the treatments here was substantially shorter and we wanted to avoid any toxicity by this agent. While the reason for maximal induction of eIF2α phosphorylation by the combined stress is unclear, it is likely due to the activation of the GADD34-PP1 negative feedback loop responsible for dephosphorylating eIF2α which may limit further phosphorylation of eIF2α(28, 29).

Figure 2. Bortezomib enhances UPR signaling under normoxia and hypoxia.

(A) ATF4 levels in HeLa cells exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 2h before treatment with DMSO or bortezomib for 6h. Thapsigargin (TH; 1μM, 4h) was used as a positivecontrol. CHOP levels in HeLa cells exposed to hypoxia 6h before treatment with DMSO or bortezomib for 12h. Thapsigargin (TH; 500nM, 12h) was used as a positive control. Nuclear protein was isolated and immunoblotted for ATF4 and CHOP; lamin A/C (loading control). (B) Active XBP-1 protein (XBP-1376aa) was induced in HeLa cells exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 6h before treatment with DMSO or bortezomib for 18h. Thapsigargin (1μM, 12h) was used as a control. Nuclear protein was isolated and immunoblotted for XBP-1; lamin A/C (loading control). (C) HT1080-ATF4-Luc cells were treated with DMSO or bortezomib and luminescence was measured 8h later. (D) Left Panel: mice with HT1080-CMV-Luc tumors on the left flank and HT1080-ATF4-Luc tumors on the right flank were given IP injections of the vehicle or bortezomib (1mg/kg) and imaged for optical bioluminescence 8h later. Right panel: Quantitation of in vivo bioluminescence of mice shown on the left panel. Results are normalized to CMV-luc activity in untreated (vehicle-injected) animals.

To assess the activity of the IRE1-dependent UPR pathway under these conditions, we examined XBP-1 mRNA splicing and the accumulation of the active XBP-1 protein. Bortezomib alone led to an accumulation of the spliced XBP-1 mRNA in a dose-dependent manner as detected by RT-PCR (Fig. S2B-C). XBP-1 mRNA splicing was induced by hypoxia alone; however, the amount of spliced XBP-1 mRNA was not further enhanced by the addition of bortezomib, indicating a binary “on-off” rather than a graded response to hypoxia.

The spliced mRNA encodes for the larger, functional XBP-1 (XBP-1376aa) transcription factor, which can be distinguished from the non-functional protein (XBP-1261aa) encoded by the unprocessed XBP-1 mRNA by their difference in electrophoretic mobilities(10). In HeLa cells treated with bortezomib under normoxic conditions, only at the higher doses were both forms of XBP-1 protein detected (Fig. 2B). The accumulation of the XBP-1261aa protein in the presence of bortezomib suggests this form was stabilized in the absence of a functional proteasome. Hypoxia alone induced the expression of XBP-1376aa which was further enhanced by bortezomib, suggesting all available spliced XBP-1 mRNA being processed is translated into the active transcription factor. Altogether, these results demonstrate that bortezomib hyperactivates both the PERK and IRE1 arms of the UPR in hypoxic tumor cells.

Bortezomib treatment increases UPR reporter gene activity in vitro and in vivo

We further examined the effects of bortezomib using an ATF4-luciferase reporter in vitro and in vivo. HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells were stably-transfected with a luciferase reporter gene fused to the 5′ UTR region of ATF4 which confers translational upregulation to any 5′-fused heterologous reporter gene under conditions of ER stress in a PERK-dependent manner (Fig. S3). Bortezomib induced a dose-dependent and time-dependent increase in ATF4-luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 2C). We also tested whether bortezomib could activate the reporter in an in vivo tumor model by using the ATF4-luciferase expressing HT1080 cells to grow tumor xenografts in nude mice. All tumors exhibited a basal level of ATF4-luciferase reporter activity, likely reflecting activation by ER stress produced by the tumor microenvironment. However, the tumors treated with bortezomib showed an increase in bioluminescence after 8h compared to the vehicle-treated tumors (Fig. 2D), demonstrating that bortezomib enhanced the ATF4-luciferase reporter activity in vivo. These results suggest that bortezomib can further increase the levels of ER stress produced by the tumor microenvironment.

Ameliorating ER stress protects hypoxic tumor cells from bortezomib

The results thus far suggested that the enhanced cytotoxicity produced by the combination of hypoxia and bortezomib induced levels of ER stress incompatible with tumor cell survival. Therefore, we hypothesized that amelioration of ER protein load should reduce the cytotoxicity of the combined treatment. We examined the effects of cycloheximide (CHX), previously shown to decrease ER stress by reducing the overall levels of client proteins in the ER(30), on XBP-1 mRNA splicing under the combined treatment. CHX blocked IRE1-dependent XBP-1 splicing in HeLa cells by both individual treatments as well as the combination (Fig. 3A). More importantly, CHX significantly reduced the cytotoxic effect of bortezomib in HeLa cells (Fig. 3B). This effect was more pronounced under hypoxic conditions, indicating the overall amount of ER stress produced by the combination of limited oxygen availability and proteasome inhibition led to increased lethality to tumor cells.

Figure 3. Ameliorating ER stress with CHX reverses the enhanced cytotoxic activity of bortezomib towards hypoxic tumor cells.

(A) Unspliced XBP-1U (473bp) and spliced XBP-1S (447bp) mRNA detected by RT-PCR on RNA from HeLa cells exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 6h before treatment with DMSO, bortezomib and cycloheximide (1μg/ml) for 18h. Thapsigargin (250nM, 8h) was used as a control; GAPDH (loading control). (B) Clonogenic survival of HeLa cells exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 12h before treatment with DMSO, bortezomib and cycloheximide (1μg/ml) for 24h. Experiments were performed in triplicate and error bars represent S.E. values.

To further examine the role of increased ER stress in the enhanced sensitivity of tumor cells to the combined effects of hypoxia and bortezomib, we exposed cells lacking a functional UPR to the combination treatment. PERK−/− MEFs are more sensitive to ER stressors, including thapsigargin and hypoxia, compared to PERK+/+ MEFs(4, 30, 31). PERK−/− MEFs were more sensitive to the combination of hypoxia and bortezomib compared to MEFs with wild-type PERK function (Fig. S4), indicating that the cytotoxicity of bortezomib to hypoxic cells resulted from the high levels of ER stress generated being incompatible with cell survival.

Hypoxic tumor cells treated with bortezomib undergo apoptosis and autophagy

To further investigate the mechanism of cell death under hypoxia and bortezomib, we analyzed the expression of apoptotic markers in DLD1 and HeLa cells. In DLD1 cells, bortezomib induced cleavage of PARP (Fig. 4A) and processing of caspase-4 (Fig. S5A), which has been implicated in ER stress-induced apoptosis(32). This activity was enhanced under hypoxia. In HeLa cells, bortezomib induced similar processing of PARP, caspase-3 and caspase-4. Surprisingly, the processing of PARP and caspase-3 in HeLa cells was completely abolished under severe or moderate hypoxia (Fig. 4B, Fig. S5B), suggesting that pre-exposure to hypoxia blocked apoptosis induced by bortezomib downstream of caspase-4 but upstream of caspase-3 and PARP cleavage. This lack of terminal apoptosis was also supported by the fact that bortezomib did not significantly enhance the sub-G1 population (Fig. S5C) in hypoxic HeLa cells. These results suggested that although the combined effects of hypoxia and bortezomib led to increased cell death in several tumor cell types, the mode of cell death induced by the combined treatment was cell-type dependent.

Figure 4. Bortezomib induces apoptotic cell death in hypoxic DLD1 but not in HeLa cells.

(A) DLD1 cells were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 12h before treatment with DMSO or bortezomib for 24h. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies specific for cleaved PARP and β-actin (loading control). (B) HeLa cells were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 12h before treatment with DMSO or bortezomib for 24h. Staurosporine (STS; 1μM, 4hr) was used as a control. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies specific for cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP and β-actin (loading control).

Previous work in yeast(33, 34) and mammalian cells(35, 36) established that ER stress can activate autophagy, a highly conserved lysosome-dependent mechanism for degrading intracellular constituents. It has been proposed that autophagy, as a pro-survival mechanism under short-term nutrient deprivation, can counteract apoptotic mechanisms and that the inhibition of autophagy makes cells more susceptible to stress-induced apoptosis(37). Interestingly, hypoxic HeLa cells treated with bortezomib had more and larger cytoplasmic vacuoles compared to similarly treated normoxic HeLa cells, suggesting that autophagy was occurring under these conditions (Fig. S6A). The LC3-II protein, processed from the phosphatidylethanolamine conjugation of LC3-I, translocates to the autophagosome membrane, and is used as a marker of autophagy(38). GFP-LC3 remained mostly cytoplasmic in HeLa cells treated with DMSO or bortezomib alone while it appeared more punctate in hypoxic HeLa cells (Fig. 5A). HeLa cells treated under hypoxia with chloroquine, an agent known to increase the lysosomal pH and allow for LC3-II accumulation, exhibited a strong punctate pattern indicating that most of the GFP-LC3 was incorporated into autophagosome membranes. A similar pattern of GFP-LC3 was seen in the hypoxic HeLa cells treated with bortezomib. Electron microscopy (Fig. S6B) confirmed that the vesicles formed in hypoxic HeLa cells treated with 20nM bortezomib exhibited the classic double membrane morphology characteristic of autophagosomes. To quantitate the level of autophagy under these conditions, we analyzed the intensity of acridine orange staining in normoxic and hypoxic HeLa cells treated with bortezomib. While bortezomib alone increased the intensity of acridine orange staining, the levels under hypoxia were further enhanced with bortezomib (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Bortezomib induces increased autophagy in hypoxic HeLa cells.

(A) HeLa cells 24h-post transfection with GFP-LC3 were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions with bortezomib for 4h. Chloroquine (CQ; 10μM, 4h) was used as a control. Two different cells are shown for each treatment. (B) HeLa cells were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 6h before treatment with DMSO or bortezomib for 18h. EBSS was used as a control. Cells were stained with acridine orange and red fluorescence was detected by flow analysis. (C) HeLa cells were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 12h before treatment with DMSO or bortezomib for 24h. Chloroquine (10μM) was present during the last 4h of treatment. TRAIL (TR; 50ng/ml, 4h) was used as a control. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies specific for cleaved PARP and β-actin (loading control). (D) HeLa cells, transfected with si RNA against Beclin1 or a non-targeting control siRNA, were treated 30h-post transfection as in B. Staurosporine (STS; 1μM, 4hr) was used as a control. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies specific for Beclin1, cleaved PARP and β-actin (loading control).

To test if HeLa cells activate autophagy as a survival response under low oxygen and proteasome inhibition, we blocked autophagy with pharmacologic and genetic ablation. HeLa cells treated during the last 4h of bortezomib treatment with chloroquine, which inhibits the progression of autophagy(39), led to increased levels of cleaved PARP in hypoxic cells (Fig. 5C), indicating that blocking autophagy under the combined treatment led to enhanced apoptosis. Knockdown of Beclin1, an important regulator of autophagy(40), by siRNA in hypoxic HeLa cells treated with bortezomib, resulted in increased PARP cleavage (Fig. 5D). However, overall clonogenic survival was not substantially altered (Fig. S6C), suggesting that hypoxic HeLa cells activated autophagy as an adaptive response that initially blocked bortezomib-induced apoptosis but did not ultimately prevent cell death.

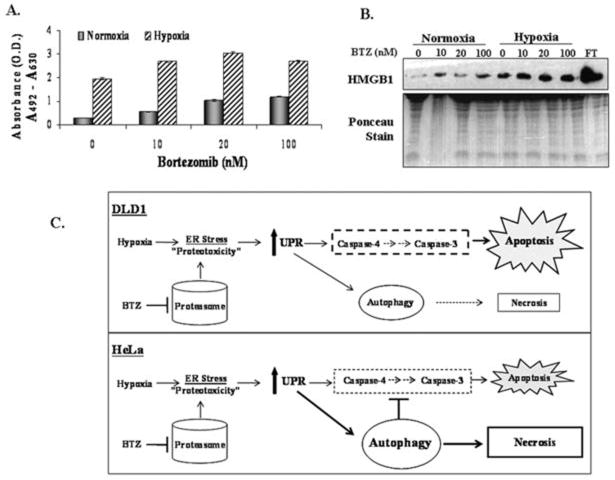

Hypoxic HeLa cells treated with bortezomib undergo necrosis

Previous work suggested that necrosis, yet another form of cell death, may be triggered by metabolic stress under conditions of defective apoptosis or prolonged autophagy(37). Therefore we analyzed the extracellular activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and levels of HMGB1, two markers of necrosis. LDH, a cytoplasmic enzyme, and HMGB1, a chromatin-binding protein, are released into the extracellular space under conditions that compromise the integrity of the plasma membrane (41). While there was very low LDH activity detected in the media of HeLa cells treated with bortezomib under normoxic conditions, it was increased in bortezomib-treated hypoxic cells (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, bortezomib enhanced the levels of HMGB1 in the extracellular media of hypoxic HeLa cells compared to normoxic cells (Fig. 6B), suggesting that the increase in HeLa cell lethality induced by the combination of bortezomib and hypoxia correlated with enhanced necrosis.

Figure 6. Hypoxic HeLa cells treated with bortezomib undergo necrotic death.

(A) HeLa cells were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 12h before treatment with DMSO or bortezomib for 24h. LDH activity was assayed in media off each sample at the indicated doses. Error bars represent s.e. values. (B) Protein was isolated from the media off HeLa cells treated as in A. Freeze/thawed HeLa cells (FT) were used as a control. Immunoblotting was performed using an antibody specific for HMGB1; the Ponceau-stained membrane is shown as a loading control. (C). Model describing the lethal effects of the combination of hypoxia and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in DLD1 cells (top) or HeLa cells (bottom). See Discussion for more details.

Discussion

We have investigated the effects of combining ER stressors with the physiologic stress of hypoxia on tumor cells. While we found that hypoxia and bortezomib individually induce ER stress by allowing unfolded proteins to accumulate in the ER, combining these stresses together enhances UPR activity and cytototoxicity against solid tumor cells. Importantly, reducing the protein burden on the ER with cycloheximide alleviates not only UPR signaling but also the cytotoxicity of either stress alone and in combination, suggesting that the severe toxicity of hypoxia and bortezomib combined is induced by the increased amount of ER stress generated. Interestingly, the mechanism of clonogenic cell death is different in the two tumor cell types tested. In DLD1 cells, the ER stress generated by hypoxia and bortezomib induced significant ER-dependent apoptosis (Fig. 6C, top). However, HeLa cells responded to the combined treatment by robust activation of autophagy, which blocked apoptosis and eventually led to necrotic cell death (Fig. 6C, bottom). It is possible that some tumor cells like DLD1 either have a lower apoptotic threshold or the kinetics of apoptosis are more rapid compared to cells like HeLa in which the combined treatment leads to autophagy.

While several studies have now established that proteasome inhibitors activate the UPR, there are reports suggesting they may compromise UPR signaling. Lee et al. reported the sensitivity of myeloma cells to proteasome inhibition was in part due to disrupted IRE1-mediated signaling(16). Similarly, MG132 did not appreciably activate IRE1 or ATF6 in MEFs, but led to GCN2-dependent eIF2α phosphorylation and reduced rates of translation(42). Our results demonstrate that solid tumor cells treated with bortezomib under normoxic and hypoxic conditions upregulated the PERK and IRE-dependent arms of the UPR (Fig. 2). These apparent differences likely reflect variations in the UPR pathways in the cell types used (e.g., multiple myeloma vs. cervical or colorectal carcinoma) or the treatment durations and doses of the proteasome inhibitors. In our study, we examined the effects of bortezomib at low, physiologic doses which have been reported to exist in the plasma of bortezomib-treated patients. Interestingly, in agreement with the report by Lee et al., we also observed upregulation of unspliced XBP-1 protein by bortezomib treatment, which could inhibit spliced XBP-1(16). However, under hypoxic conditions, XBP-1 splicing was complete and no accumulation of the smaller XBP-1 protein was evident, suggesting that the combination of bortezomib and hypoxia led to UPR overactivation.

Autophagy can provide a survival advantage for tumor cells in regions of metabolic stress, such as in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment(37, 43). Since autophagy is generally viewed as a pro-survival mechanism and an impediment to chemotherapy, our findings suggest that it may be possible to overcome this pro-survival pathway induced by hypoxia and “push” hypoxic tumor cells into necrosis by overactivating ER stress-dependent mechanisms. It will be interesting to test the combined effects of bortezomib and autophagy inhibitors like chloroquine in vivo, which we predict will show even greater cytotoxicity towards hypoxic tumor cells.

The precise mechanism of hypoxia-induced, ER-dependent cell death is still unknown. One potential player may be the pro-apoptotic protein CHOP. In agreement with other reports(18, 19), CHOP was induced by bortezomib, hypoxia and the combined treatment. However, markers of terminal apoptosis were not detected in HeLa cells under the combination treatment even in the presence of CHOP, suggesting that autophagy may also be able to block the pro-death functions of CHOP. Caspase-4 is also activated by the IRE1-TRAF2-ASK1 complex which is induced upon ER stress(44). Indeed, others have reported that bortezomib can induce phosphorylation of JNK(18), which is also involved in proteasome inhibition-induced autophagy and important for tumor cell survival after ER stress(36, 45). Although our results point to enhanced ER stress-induced events in tumor cells under the combined stresses of hypoxia and proteasome inhibition, we cannot exclude the possibility that other, non-ER dependent pathways, may also be involved. For example, some of bortezomib’s cytotoxic effects towards hypoxic tumor cells could be due to the inhibition of NF-κB via IκB stabilization(15). However, our findings that thapsigargin, an ER stressor with a different mode of action from proteasome inhibitors exhibits similarly preferential cytotoxicity towards hypoxic tumor cells, supports the notion that the combined cytotoxicity occurs through an ER stress-dependent mechanism.

A recent report by Shin et al. indicates that bortezomib, despite increasing HIF-1α levels, actually inhibited HIF-1α transcriptional activity by enhancing the interaction with the factor inhibiting HIF (FIH)(46). These findings suggest that bortezomib’s inhibitory effects on angiogenesis and increased cell death may involve the inhibition of HIF-1α activity. Although we cannot rule out a role for HIF-1α inhibition in increasing bortezomib-induced lethality towards hypoxic tumor cells, it is unlikely that this mechanism plays a significant role in this response for the following reasons: First, as mentioned earlier, UPR activation under hypoxia was found to occur independently of HIF-1α status, as HIF-1α−/− MEFs exhibited similar levels of eIF2α phosphorylation as HIF-1α+/+ MEFs(4). Second, thapsigargin, an ER stressor that does not inhibit HIF-1α levels or activity, demonstrates a similar synergy with hypoxia as bortezomib. Third, it has been shown that HIF-1α plays little, if any, role in promoting epithelial cell survival under stringent hypoxic conditions. The fact that thapsigargin causes ER stress by a different mechanism than bortezomib and also preferentially kills hypoxic tumor cells argues against a HIF-mediated role in this response, at least in the epithelial cell lines tested.

Currently, tumor hypoxia represents a significant clinical problem. However, the reliance of hypoxic tumor cells on a functional UPR may provide a unique therapeutic opportunity. Indeed, the concept of hypoxia selective cytotoxicity has received significant attention and one such hypoxia-selective agent, tirapazamine, is in late phase clinical trials(1). One approach to target the UPR in tumors is to develop inhibitors that would compromise UPR signaling via PERK, IRE1 or molecular chaperones like GRP78/BiP(47, 48) and screening of small molecule libraries is underway by several groups (Koong et al, unpublished results). Our findings suggest a second approach for targeting the UPR in hypoxic tumor cells, which relies on a clinically used agent to hyperactivate the UPR in hypoxic cells. As only a fraction of a patient’s tumor is hypoxic at any given time, administering low doses of an ER stressor such as bortezomib is unlikely to eradicate the bulk of the tumor and provide efficient tumor control. However, we propose that the significance of our findings lie in the opportunity to incorporate bortezomib with other modalities like radiotherapy and chemotherapy which preferentially target normoxic tumor cells with the expectation that killing the hypoxic cells will allow for more effective tumor control and longer overall patient survival.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by NIH grants CA94214 to DRF, JY, ATS, SK and CK and CA112108 to MS, MO, and ACK.

We thank Drs. Julian Lum and Craig Thompson (Univ. of Pennsylvania) for the GFP-LC3 plasmid, the anti-LC3 antibody and for helpful discussions; Dr. Andrew Thorburn (Univ. of Colorado) for the pcDNA3.1/GFP-LC3 plasmid and Dr. Serge Fuchs (Univ. of Pennsylvania) for critically reading our manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants CA94214 to CK and CA112108 to AK.

References

- 1.Brown JM. Tumor hypoxia in cancer therapy. Methods Enzymol. 2007;435:297–321. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)35015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–32. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le QT, Denko NC, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxic gene expression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:293–310. doi: 10.1023/B:CANC.0000031768.89246.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koumenis C, Naczki C, Koritzinsky M, et al. Regulation of protein synthesis by hypoxia via activation of the endoplasmic reticulum kinase PERK and phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7405–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7405-7416.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blais JD, Filipenko V, Bi M, et al. Activating Transcription Factor 4 Is Translationally Regulated by Hypoxic Stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7469–82. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7469-7482.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koritzinsky MMM, van den Beucken T, Seigneuric R, Savelkouls K, Dostie J, Pyronnet S, Kaufman RJ, Weppler SA, Voncken JW, Lambin P, Koumenis C, Sonenberg N, Wouters BG. Gene expression during acute and prolonged hypoxia is regulated by distinct mechanisms of translational control. Embo J. 2006;25:1114–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu L, Cash TP, Jones RG, Keith B, Thompson CB, Simon MC. Hypoxia-Induced Energy Stress Regulates mRNA Translation and Cell Growth. Molecular Cell. 2006;21:521–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bi M, Naczki C, Koritzinsky M, et al. ER stress-regulated translation increases tolerance to extreme hypoxia and promotes tumor growth. Embo J. 2005;24:3470–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, et al. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–6. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang X, et al. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–95. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and Genomic Analyses Reveal an Essential Coordination between the Unfolded Protein Response and ER-Associated Degradation. Cell. 2000;101:249–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson PG, Mitsiades C, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. BORTEZOMIB: Proteasome Inhibition as an Effective Anticancer Therapy. Annual Review of Medicine. 2006;57:33–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.042905.122625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hideshima T, Richardson P, Chauhan D, et al. The Proteasome Inhibitor PS-341 Inhibits Growth, Induces Apoptosis, and Overcomes Drug Resistance in Human Multiple Myeloma Cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3071–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee A-H, Iwakoshi NN, Anderson KC, Glimcher LH. Proteasome inhibitors disrupt the unfolded protein response in myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9946–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1334037100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fribley A, Zeng Q, Wang C-Y. Proteasome Inhibitor PS-341 Induces Apoptosis through Induction of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Reactive Oxygen Species in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9695–704. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9695-9704.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nawrocki ST, Carew JS, Dunner K, Jr, et al. Bortezomib Inhibits PKR-Like Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Kinase and Induces Apoptosis via ER Stress in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11510–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obeng E, Carlson L, Gutman D, Harrington JW, Lee KLHB. Proteasome inhibitors induce a terminal unfolded protein response in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107:4907–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy RK, Mao C, Baumeister P, Austin RC, Kaufman RJ, Lee AS. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein GRP78 protects cells from apoptosis induced by topoisomerase inhibitors: role of ATP binding site in suppression of caspase-7 activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20915–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212328200. Epub 2003 Mar 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong D, Ni M, Li J, et al. Critical Role of the Stress Chaperone GRP78/BiP in Tumor Proliferation, Survival, and Tumor Angiogenesis in Transgene-Induced Mammary Tumor Development. Cancer Res. 2008;68:498–505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pyrko P, Schonthal AH, Hofman FM, Chen TC, Lee AS. The Unfolded Protein Response Regulator GRP78/BiP as a Novel Target for Increasing Chemosensitivity in Malignant Gliomas. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9809–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ameri K, Lewis CE, Raida M, Sowter H, Hai T, Harris AL. Anoxic induction of ATF-4 through HIF-1-independent pathways of protein stabilization in human cancer cells. Blood. 2004;103:1876–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koditz J, Nesper J, Wottawa M, et al. Oxygen-dependent ATF-4 stability is mediated by the PHD3 oxygen sensor. Blood. 2007;110:3610–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero-Ramirez L, Cao H, Nelson D, et al. XBP1 Is Essential for Survival under Hypoxic Conditions and Is Required for Tumor Growth. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5943–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denmeade SR, Jakobsen CM, Janssen S, et al. Prostate-Specific Antigen-Activated Thapsigargin Prodrug as Targeted Therapy for Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:990–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.13.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veschini L, Belloni D, Foglieni C, et al. Hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-1 alpha determines sensitivity of endothelial cells to the proteosome inhibitor bortezomib. Blood. 2007;109:2565–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-032664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novoa IZY, Zeng H, Jungreis R, Harding HP, Ron D. Stress-induced gene expression requires programmed recovery from translational repression. Embo J. 2003;22:1180–7. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Y, Hendershot LM. Delineation of a Negative Feedback Regulatory Loop That Controls Protein Translation during Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34864–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheuner D, Song B, McEwen E, et al. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1165–76. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hitomi J, Katayama T, Eguchi Y, et al. Involvement of caspase-4 in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and A{beta}-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:347–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernales SMK, Walter P. Autophagy Counterbalances Endoplasmic Reticulum Expansion during the Unfolded Protein Response. PLoS Biology. 2006;4:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yorimitsu T, Nair U, Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Triggers Autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30299–304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kouroku Y, Fujita E, Tanida I, et al. ER stress (PERK/eIF2alpha phosphorylation) mediates the polyglutamine-induced LC3 conversion, an essential step for autophagy formation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:230–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401984. Epub 2006 Jun 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogata M, Hino S-i, Saito A, et al. Autophagy Is Activated for Cell Survival after Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9220–31. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, et al. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabeya YMN, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. Embo J. 2000;19:5720–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amaravadi RK, Thompson CB. The Roles of Therapy-Induced Autophagy and Necrosis in Cancer Treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7271–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–6. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191–5. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang H-Y, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of the {alpha}-Subunit of the Eukaryotic Initiation Factor-2 (eIF2{alpha}) Reduces Protein Synthesis and Enhances Apoptosis in Response to Proteasome Inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14189–202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karantza-Wadsworth V, Patel S, Kravchuk O, et al. Autophagy mitigates metabolic stress and genome damage in mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1621–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.1565707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–6. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding W-X, Ni H-M, Gao W, et al. Linking of Autophagy to Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Is Important for the Regulation of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Cell Viability. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:513–24. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin DH, Chun YS, Lee DS, Huang LE, Park JW. Bortezomib inhibits tumor adaptation to hypoxia by stimulating the FIH-mediated repression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Blood. 2008;111:3131–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-120576. Epub 2008 Jan 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu Y, Lee AS. Glucose regulated proteins in cancer progression, drug resistance and immunotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:741–4. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2970. Epub 2006 Jul 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma Y, Hendershot LM. The role of the unfolded protein response in tumour development: friend or foe? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:966–77. doi: 10.1038/nrc1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]