Abstract

This study on aquaculture ponds investigated how diet sources affect methyl mercury (MeHg) bioaccumulation of the worldwide key diet fish, common carp (Cyprinus carpio). We tested how MeHg concentrations of one and two year-old pond-raised carp changed with different food quality: a) zooplankton (natural pond diet), b) cereals enriched with vegetable oil (VO ponds), and c) compound feeds enriched with marine fish oils (FO ponds). It was hypothesized that carp preferentially feed on supplementary diets with the highest biochemical quality (FO diet over VO diets over zooplankton). Although MeHg concentrations were highest in zooplankton of FO ponds, MeHg concentrations of carp were clearly lower in FO ponds (17–32 ng g− 1 dry weight) compared to the reference (40–46 ng g− 1 dry weight) and VO ponds (55–86 ng g− 1 dry weight). Stable isotope mixing models (δ13C, δ15N) indicated selective feeding of carp on high quality FO diets that caused MeHg concentrations of carp to decrease with increasing dietary proportions of supplementary FO feeds. Results demonstrate that carp selectively feed on diets of highest biochemical quality and strongly suggest that high diet quality can reduce MeHg bioaccumulation in farm-raised carp.

Keywords: Methyl mercury, Stable isotopes, Trophic transfer, Common carp

Highlights

► Common carp of semi-intensive aquacultures feed on natural and artificial food sources. ► Main dietary sources of methyl mercury of cultivated common carp are identified. ► Carp actively select diets of highest biochemical quality. ► Carp preferentially feed on artificial diets based on marine fish oils. ► Artificial diets reduce methyl mercury accumulation of cultivated common carp.

1. Introduction

The potent neurotoxin methyl mercury (MeHg) bioaccumulates in aquatic organisms from lower to higher trophic levels and with increasing body size and age (Kainz et al., 2006, 2008; McIntyre and Beauchamp, 2007). Methyl Hg may negatively affect human health (Clarkson, 2002; Guallar et al., 2002) as concentrations in diet fish increase with increasing trophic position, thus with the length of the food chain (Power et al., 2002; Vander Zanden and Rasmussen, 1996). In the case of planktivorous and benthivorous fish raised in semi-intensive aquaculture (Valente et al., 2011), the use of formulated compound feeds based on fish from marine sources may represent an ‘artificial elongation’ of their food chain that may thus cause a higher dietary MeHg supply to fish. Such additional diet supply may equally increase somatic growth performance of fish, which also results in a higher productivity of aquaculture systems. However, the effects of supplementary fish feeds on MeHg concentrations in fish are still contradictory. For example, while Foran et al. (2004) found no effects of supplementary feeding of formulated compound feeds on MeHg bioaccumulation in aquaculture fish (i.e., Salmo salar), other studies reported higher MeHg concentrations in a variety of aquaculture fish when exposed to supplementary, marine fish-based feeds (Berntssen et al., 2010; Cheung et al., 2008). However, elucidating such differing effects of MeHg bioaccumulation requires a mechanistic explanation.

Understanding how dietary MeHg affects its bioaccumulation in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.), as a major diet fish worldwide (FAO, 2008), is crucial, yet thus far poorly understood. In semi-intensive aquaculture, carp are exposed to different diet sources: zooplankton and benthic organisms are natural sources, whereas cereals or formulated pellet feeds represent supplementary diet sources. As cultured freshwater fish species are an important source of protein and essential fatty acids for landlocked countries (Arts et al., 2001; Steffens and Wirth, 2007; Zheng et al., 2005), current and future knowledge about the possibilities of modulating diet quality with respect to the requirements of fish species and human nutrition should be used to produce sustainable, high-quality fish for human consumption. Thus, the potential risks of feeding commercial diets to farm-raised fish include MeHg bioaccumulation that needs to be assessed to gain an understanding of how different food sources affect MeHg bioaccumulation in carp.

The aim of this study was to evaluate how natural and supplementary diet sources affect MeHg concentrations of one (K1) and two (K2) year-old farm-raised common carp. The dietary effect on MeHg bioaccumulation can be best investigated during the early ontogeny of carp, as prior to sexual maturity the potential allocation of contaminants to reproductive tissue is negligible (Muus and Dahlström, 1998).

Based on previous results showing that marine fish-based feeds are of high biochemical quality and contain, in particular, higher concentrations of beneficial polyunsaturated fatty acids than VO based feeds (Olsen, 1999; Turchini et al., 2009), it was hypothesized that carp preferentially feed on and retain supplementary FO diets over VO based diets and natural zooplankton. It is expected that the results of this study will provide detailed information on how MeHg bioaccumulation in carp is affected by diet sources and can thus be manipulated using different diet quality. Furthermore, these results will help to identify the main dietary routes of MeHg bioaccumulation in fish produced using semi-intensive aquaculture (Valente et al., 2011).

2. Materials and methods

MeHg bioaccumulation in one- (K1) and two-year (K2) old common carp (C. carpio L.) was investigated over two growth seasons (K1-carp: 2008 and K2-carp: 2009), respectively, in six aquaculture ponds in temperate Lower Austria (N 48.815049, E 15.297321). In April, carp from the same stock were introduced to six different ponds, of which five were supplemented with feeds of different dietary qualities according to established aquaculture practice. The quality with respect to nutritional values was defined by different lipid concentrations (high lipid concentration = higher quality) and their sources (vegetable oils = medium quality; fish oils = high quality).

The reference pond only contained a natural pond diet, i.e., zooplankton. Fish of ponds 2 and 3 additionally received a commonly used cereal diet (triticale) with 1% (VO1) and 3% (VO3) milk thistle oil supplements (vegetable oil; VO). Carp of ponds 4, 5, and 6 additionally obtained commercial compound feeds based on marine fish meal, enriched with marine fish oil (FO) of different lipid concentrations; i.e., 6% (FO6), 10% (FO10), and 18% (FO18). This setup was chosen to investigate the relationships among different diet qualities and MeHg bioaccumulation in common carp under ‘real world’ aquaculture conditions. Feeds were supplied using pendulum feeders that were activated by the fish.

The quantity of feed supply and stocking rates of carp were designed according to established aquaculture methods. The quantity of supplementary fish feed applied per fish was 0.24 ± 0.06 kg year− 1 (2008) for K1-carp and 1.22 ± 0.24 kg year− 1 (2009) for K2-carp of each pond. The nutritional values of the marine compound feeds were provided by the manufacturer (Garant-Tiernahrung™, Austria; Table 1).

Table 1.

Relative composition (> 0.5%) and ingredients of commercial compound feeds (Garant-Tiernahrung™, Austria).

| Composition | FO6 | FO10 | FO18 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude protein | 30.0 | 32.0 | 36.0 |

| Total lipids | 6.0 | 10.0 | 18.0 |

| Fiber | 3.8 | 3.3 | 2.5 |

| Ash | 12.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Ingredients | FO6 | FO10 | FO18 |

| Soybean meal | 29.9 | 24.5 | 25.3 |

| Wheat | 14.0 | 14.2 | 13.3 |

| Rapeseed press cake | 12.5 | 10.0 | 7.5 |

| Corn | 10.0 | 7.5 | 3.5 |

| Wheat flour | 10.0 | 7.5 | – |

| Peas | 7.5 | 7.5 | 5.0 |

| Fish meal (68%) | 6.7 | 14.4 | 24.3 |

| Soy beans | 2.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Fish oil | 2.3 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Fish oil (sprayed on) | – | 2.7 | 10.5 |

| Monocalciumphosphate | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| Calcium carbonate | 1. 6 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

2.1. Sampling

Carp (K1, n = 10; K2, n = 5–7; per pond and campaign) and corresponding zooplankton of each pond were collected after 100 (July, summer campaign) and 200 days of the growth season (November; fall campaign). For logistical reasons it was not possible to collect carp from the reference pond during summer and from the pond supplied with diet VO1 in fall 2008. Fish were measured (± 0.1 cm), weighed (± 0.1 g), and kept frozen (− 80 °C) until further analyses.

Zooplankton was sampled at each pond using net tows (100 μm mesh size), subsequently separated into different size fractions (250–500 μm and > 500 μm) by using a separation tower, and kept frozen (− 80 °C) until further analyses. These two larger size classes were used as they represented the primary natural food source of farm-raised common carp (Schlott, 2007).

2.2. MeHg analysis of carp and corresponding diets

Methyl Hg was analyzed (triplicates) for each pond from freeze-dried, homogenized fish (fall campaign) and supplementary fish feeds (approximately 250 mg) as described by Vallant et al. (2007). In brief, the extraction of MeHg was conducted by ultrasonic extraction in the mobile phase utilized for chromatographic separation. An aliquot of the extract was filtered (0.22 μm) and analyzed using HPLC coupled to an ICP-MS. The most abundant mercury isotope (m/z 202) was used for data evaluation. Subsequently, MeHg was quantified compared to known standards. For MeHg analysis of freeze-dried zooplankton (0.5–1 mg; summer and fall samples), organisms were homogenized and digested in 0.5 mL of a KOH/MeOH (1 g · 4 mL− 1) solution for 8 h at 70 °C. MeHg was separated by GC and subsequently quantified using atomic fluorescence spectrometry (Pichet et al., 1999). Means (± SD) of analytical duplicates were reported and precision and reproducibility were evaluated using known MeHg standards and certified reference materials (NIST 2976, IAEA 405 and TORT-2 with recovery rates of 97, 95 and 101%, respectively).

2.3. Stable isotopes analysis and 13C lipid correction

Signatures of stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) of freeze-dried and homogenized fish, zooplankton, and supplementary feed samples (≈ 1 mg) were analyzed using an elemental analyzer (EA 1110, CE Instruments, Milan, Italy) interfaced via a ConFloII device (Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) to a continuous flow stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta Plus, Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) as described elsewhere (Göttlicher et al., 2006; Watzka et al., 2006). Nitrogen (Air Liquide™) and CO2 were used as reference gases. Calibration was performed using the air international standard IAEA-N-1, IAEA-N-2, and IAEA-NO-3 (IAEA, Vienna, Austria) for nitrogen and IAEA-CH-6, IAEA-CH-7 (International Atomic Energy Agency) for carbon. The standard deviations (SD) of repeated measurements of laboratory standards were 0.10‰ and 0.15‰ for δ13C and δ15N, respectively.

A lipid correction was applied to 13C values, based on the model of McConnaughey and McRoy (1979), as values for 13C in lipids were generally depleted compared to values of lipid extracted tissues (Kiljunen et al., 2006). The model used C:N ratios as a proxy for total lipid contents and normalized 13C values of samples varying to large extent in lipid concentrations (e.g., fish and zooplankton). The proportional lipid content (L) and lipid-normalized δ13C values were defined as:

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

where δ13C′ is the lipid-normalized value of the sample and δ13C the measured value of the sample. L represents the proportional lipid content of the sample and C:N the proportion of carbon and nitrogen in the sample. The protein-lipid discrimination (D) was set to 7‰ as suggested by Sweeting et al. (2007). I defines the intersection on the x-axis (Kiljunen et al., 2006) and assigned a value of − 0.207.

All stable isotope values were reported in the δ notation where δ13C or δ15N = ([Rsample / Rstandard] − 1) × 1000 were 13C:12C or 15N:14N (Peterson and Fry, 1987).

2.4. Food source identification/mixing models

The dietary contribution of zooplankton and added feeds to the carp diets was assessed using SIAR (Stable Isotope Analysis in R). Fractionation factors of 13C and 15N between trophic levels (i.e., potential food sources and carp) were set at 1.1 ± 0.3‰ and 2.8 ± 0.4‰ for C and N, respectively (McCutchan et al., 2003). Zooplankton and the additional fish feeds were used as the only potential food sources in the mixing models as zooplankton was identified (gut content analyses) to be the major natural food source for carp in all ponds. Moreover, benthic invertebrates were absent in sediments (analyses of sediments) and carp (gut content analysis).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Differences between mean MeHg concentrations were analyzed by using non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis). For pair-wise comparisons (MeHg of carp), Mann–Whitney-U-test was used as a post hoc test and the Bonferroni–Holm's correction was applied for local alpha. Linear regression analysis (Spearson's correlation) was used to investigate relationships between food source proportions and MeHg concentrations of carp. Differences between means of fish length and weight were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post hoc tests. The level of significance of all statistical tests was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (15.0) and R.

3. Results

3.1. Zooplankton composition and fish size

Daphnia longispina and Bosmina longirostis dominated both zooplankton size classes, followed by cyclopoid (Eucyclops sp.) and, to a lesser extent, calanoid copepods (Eudiaptomus sp.). Body length and weight of K1- and K2-carp differed significantly among ponds (Table 2). K1-carp of pond VO3 were significantly larger and had significantly higher body weight than K1-carp of all other ponds. K2-carp of pond FO18 were significantly larger than fish of VO or reference ponds and had significantly higher body weight, whereas K2-carp of pond VO1 were significantly smaller and had the lowest body weight of all K2-carp.

Table 2.

Standard length (seedlings K1 = total length) and weight of one- (K1) and two- (K2) year old carp (C. carpio; mean ± SD). Same letters indicate significant differences between means among ponds (p < 0.05; Bonferroni's post hoc test). Diets: natural pond diet (Ref.), cereal diet with 1% (VO1) and 3% vegetable oil (VO3), compound feeds with 6% (FO6), 10% (FO10) and 18% fish oil (FO18). n/a: samples not available.

| Diet |

C. carpio K1 |

C. carpio K2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (cm) | Weight (g) | Length (cm) | Weight (g) | |

| Seedlings | 9.0 ± 1.5 | 10.7 ± 5.3 | 18.6 ± 2.8 | 196.6 ± 51.8 |

| Ref. | 18.5 ± 1.0a | 207.7 ± 28.0a | 27.9 ± 2.7a,b | 686.5 ± 205.5a,b,c |

| VO1 | n/a | n/a | 21.2 ± 1.9a,c,d,e,f | 268.2 ± 56.5a,d,e,f,g |

| VO3 | 24.8 ± 1.2a,b,c,d | 485.2 ± 83.0a,b,c,d | 28.6 ± 1.9c,g | 668.4 ± 114.6d,h,i,j |

| FO6 | 17.7 ± 1.3b | 173.6 ± 38.0b | 31.2 ± 1.3d | 952.6 ± 66.8e,h,k |

| FO10 | 19.5 ± 2.4c | 256.2 ± 104.7c | 31.4 ± 1.5e | 1022.5 ± 119.1b,f,i,l |

| FO18 | 19.1 ± 2.2d | 260.2 ± 91.0d | 33.6 ± 2.2b,f,g | 1413.7 ± 228.1c,g,j,k,l |

3.2. MeHg concentrations of zooplankton and supplied fish feeds

MeHg concentrations of zooplankton (Table 3) were generally higher in FO (17–264 ng g− 1) than in VO ponds or the reference pond (10–54 ng g− 1). In summer 2008, MeHg concentrations were higher in zooplankton > 500 μm of the reference pond than of ponds FO10 and FO18. In fall 2009, MeHg concentrations of medium sized zooplankton (250–500 μm) of pond FO18 were likewise slightly decreased compared to the reference pond. MeHg concentrations of zooplankton (250–500 μm) significantly differed among ponds of summer 2008 and fall 2009, whereas no significant differences among ponds were recorded during fall 2008 and summer 2009. MeHg concentrations of zooplankton > 500 μm generally differed significantly among ponds (Table 3). No MeHg concentrations were detectable in supplementary FO and VO feeds (detection limit 6 ng g− 1).

Table 3.

MeHg concentrations (ng g− 1 dry weight; mean ± SD) of zooplankton size classes. Asterisks indicate significant differences among ponds (Kruskal–Wallis-H-test, p < 0.05). Diets: natural pond diet (Ref.), cereal diet with 1% (VO1) and 3% vegetable oil (VO3), compound feeds with 6% (FO6), 10% (FO10) and 18% fish oil (FO18). n/a: samples not available.

| Diet |

250–500 μm |

> 500 μm |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Summer* | Fall | Summer* | Fall* |

| Ref. | 15.5 ± 0.7 | 25.5 ± 0.7 | 43.5 ± 2.1 | 34.0 ± 1.4 |

| VO1 | 12.5 ± 0.7 | 41.0 ± 1.4 | 10.0 ± 6.4 | 35.0 ± 9.8 |

| VO3 | 11.5 ± 0.7 | 49.5 ± 0.7 | 12.0 ± 0.0 | 38.3 ± 8.4 |

| FO6 | 87.0 ± 2.8 | 70.0 ± 2.8 | 103.0 ± 1.4 | 87.5 ± 3.5 |

| FO10 | 51.5 ± 2.1 | 151.0 ± 5.7 | 17.5 ± 0.7 | 134.5 ± 7.8 |

| FO18 | 26.5 ± 4.6 | 55.5 ± 2.1 | 35.5 ± 2.1 | 52.0 ± 2.8 |

| 2009 | Summer | Fall* | Summer | Fall* |

| Ref. | 60.2 ± 2.9 | 51.0 ± 2.8 | n/a | n/a |

| VO1 | 54.4 ± 2.6 | 21.0 ± 0.0 | n/a | 21.6 ± 2.3 |

| VO3 | 47.5 ± 0.8 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | n/a | 11.0 ± 0.0 |

| FO6 | 130.6 ± 0.3 | 228.0 ± 75.2 | 122.9 ± 3.6 | 113.0 ± 1.4 |

| FO10 | 170.4 ± 74.9 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| FO18 | 116.2 ± 5.1 | 46.0 ± 4.8 | 264.8 ± 61.6 | 70.5 ± 12.3 |

3.3. MeHg concentrations of common carp

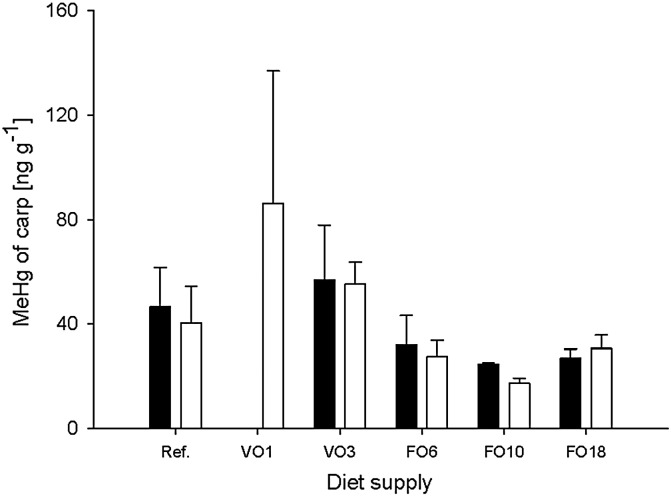

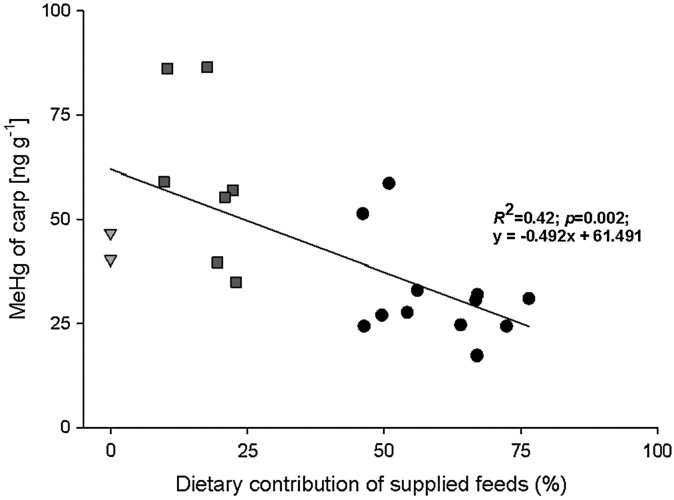

Carp generally showed a clear trend of lower MeHg concentrations in FO ponds and higher MeHg concentrations in VO ponds (up to 86 ng g− 1 dry weight in K2-carp of pond VO1). MeHg concentrations of K1- and K2-carp of VO ponds were generally higher than those of carp of the reference pond (Fig. 1). At the end of the respective growth season, MeHg concentrations differed significantly among groups of K2-carp, whereas no significant differences were found among the ponds for K1-carp. Due to high standard deviations and low local alpha, pairwise comparisons (Mann–Whitney-U-test) could not detect any significant differences between distinct ponds, but regression analysis revealed that increasing dietary proportions of additional fish feeds caused MeHg concentrations of K1 and K2-carp to decrease (Fig. 2). Feeding on different diet sources accounted for 42% of MeHg variability in carp (p < 0.002; R2 = 0.42; slope: − 0.492).

Fig. 1.

MeHg concentrations (mean ± SD; dry weight) of one-year (K1; black bars; n = 3) and two-year old carp (K2; white bars; n = 3) at the end of growing season (fall). Ponds: Natural pond diet (Ref.), cereal diet with 1% (VO1) and 3% vegetable oil (VO3), compound feeds with 6% (FO6), 10% (FO10) and 18% fish oil (FO18).

Fig. 2.

Effect of dietary food source retention on MeHg concentrations of one- and two-year old carp (summer and fall sampling). Gray triangles: natural diet (zooplankton); dark gray squares: terrestrial diets (VO1; VO3); black dots: marine compound feeds (FO6; FO10; FO18).

3.4. Stable isotopes and mixing models

Carp had generally lighter δ13C signatures (lipid corrected) when fed on VO than FO diets, whereas no diet-specific patterns of δ15N signatures were detected (Table 4). Zooplankton δ13C and δ15N signatures ranged from − 22.2‰ to − 35‰ and 3.7‰ to 12.1‰, respectively. Supplementary feeds had generally similar δ13C signatures (− 20.9‰ to − 22.7‰; but − 16.3‰ for FO6 in 2008) and δ15N signatures ranged from 2.6‰ to 7.3‰ (Table 4). Zooplankton size classes of each pond and sampling campaign did not differ in their stable isotope signatures and where pooled for the analysis of mixing models.

Table 4.

Delta-13C (lipid corrected) and δ15N signatures of one- (K1) and two- (K2) year old carp, pond zooplankton, and supplementary feeds (‰; mean ± SD). Diets: natural pond diet (Ref.), cereal diet with 1% (VO1) and 3% vegetable oil (VO3), compound feeds with 6% (FO6), 10% (FO10) and 18% fish oil (FO18). n/a: samples not available.

| 2008 | Carp K1 (summer) |

Zooplankton (summer) |

Carp K1 (fall) |

Zooplankton (fall) |

Supplementary feeds |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ13C | δ15 | δ13C | δ15N | δ13C | δ15N | δ13C | δ15N | δ13C | δ15N | |

| Ref. | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | − 31.2 ± 0.3 | 10.8 ± 0.4 | − 31.6 ± 0.3 | 8.4 ± 0.1 | n/a | n/a |

| VO1 | − 27.4 ± 0.2 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | − 24.8 ± 0.3 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | n/a | n/a | − 25.4 ± 1.0 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | − 21.9 ± 0.0 | 2.8 ± 0.0 |

| VO3 | − 29.5 ± 0.8 | 11.7 ± 0.0 | − 31.9 ± 1.0 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | − 28.2 ± 0.3 | 10.8 ± 0.2 | − 31.3 ± 0.3 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | − 22.7 ± 0.0 | 3.4 ± 0.0 |

| FO6 | − 23.0 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | − 31.5 ± 1.4 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | − 23.4 ± 0.0 | 6.9 ± 0.2 | − 22.0 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | − 16.3 ± 0.0 | 2.6 ± 0.0 |

| FO10 | − 23.0 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.4 | − 32.0 ± 0.2 | 9.2 ± 0.1 | − 22.8 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 0.1 | − 28.2 ± 0.6 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | − 20.9 ± 0.0 | 4.7 ± 0.0 |

| FO18 | − 22.5 ± 0.3 | 9.6 ± 0.2 | − 30.5 ± 0.5 | 12.1 ± 0.2 | − 22.2 ± 0.2 | 9.0 ± 0.2 | − 24.5 ± 0.2 | 8.7 ± 0.5 | − 21.0 ± 0.0 | 5.8 ± 0.0 |

| 2009 | Carp K2 (summer) | Zooplankton (summer) | Carp K2 (fall) | Zooplankton (fall) | Supplementary feeds | |||||

| δ13C | δ15N | δ13C | δ15N | δ13C | δ15N | δ13C | δ15N | δ13C | δ15N | |

| Ref. | n/a | n/a | − 35.0 ± 1.2 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | − 30.6 ± 1.7 | 10.3 ± 0.3 | − 33.8 ± 2.3 | 9.0 ± 0.3 | n/a | n/a |

| VO1 | − 25.8 ± 2.4 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | − 28.1 ± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | − 26.4 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 1.2 | − 26.1 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.0 | − 22.1 ± 0.0 | 3.1 ± 0.0 |

| VO3 | − 27.3 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | − 30.4 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | − 28.1 ± 0.1 | 7.6 ± 0.2 | − 27.9 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 1.3 | − 22.5 ± 0.0 | 3.2 ± 0.0 |

| FO6 | − 24.2 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 0.4 | − 24.7 ± 0.1 | 8.2 ± 0.4 | − 24.2 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | − 26.0 ± 0.6 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | − 21.7 ± 0.0 | 3.0 ± 0.0 |

| FO10 | − 23.5 ± 0.1 | 7.9 ± 0.2 | − 27.0 ± 0.5 | 9.6 ± 0.5 | − 23.1 ± 0.5 | 8.2 ± 0.1 | − 27.7 ± 1.8 | 8.9 ± 1.4 | − 21.2 ± 0.0 | 5.4 ± 0.0 |

| FO18 | − 24.6 ± 0.2 | 10.3 ± 0.6 | − 30.0 ± 1.0 | 7.5 ± 0.8 | − 24.2 ± 0.3 | 10.4 ± 0.4 | − 32.3 ± 0.3 | 11.0 ± 0.3 | − 21.4 ± 0.0 | 7.3 ± 0.0 |

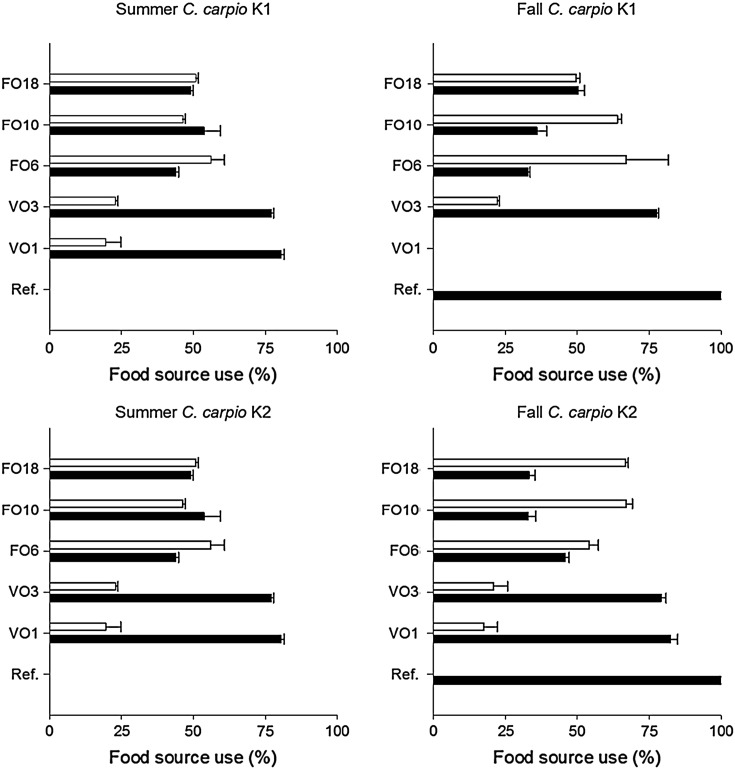

Stable isotope mixing models showed that supplied feeds contributed 59.7 ± 10.5% (46.1–76.5%, min–max) to the diets of carp of FO ponds (Fig. 3). In contrast, carp fed on VO feeds relied mostly on zooplankton and only used 17.7 ± 5.5% (9.8–22.9%, min–max) of the supplied feeds as a dietary source.

Fig. 3.

Dietary retention (SIAR mixing models) of natural diet (zooplankton; dark bars) and additional fish feeds (white bars) in one- (K1) and two-year old (K2) carp. Labels of the y-axis represent dietary supply: natural pond diet (Ref.), cereal diet with 1% (VO1) and 3% vegetable oil (VO3), compound feeds with 6% (FO6), 10% (FO10) and 18% fish oil (FO18).

4. Discussion

MeHg concentrations were lowest in carp of ponds supplied with FO diets. Carp of these ponds exhibited lower MeHg concentrations compared to carp fed exclusively on zooplankton or on additional VO diets. It is noticeable that MeHg concentrations of carp of VO and reference ponds were higher than MeHg measured in corresponding zooplankton, while MeHg concentrations of carp of FO ponds were generally lower than concentrations detected in zooplankton. These findings are unexpected as the MeHg concentrations of zooplankton of the FO ponds showed generally higher concentrations compared to those of VO or reference ponds. Because MeHg bioaccumulates in organisms with increasing trophic levels (Power et al., 2002; Vander Zanden and Rasmussen, 1996), MeHg concentrations of carp were expected to be higher than of pond zooplankton in all ponds (effect of higher trophic level). In particular, MeHg concentrations should have been higher in carp of FO ponds compared to carp of VO ponds due to the generally higher MeHg concentrations in zooplankton of FO ponds.

By selectively feeding on supplementary feeds, carp exposed to FO feeds retained lower dietary MeHg than carp of VO and reference ponds, the latter feeding mainly or exclusively on zooplankton. These results strongly indicate that MeHg concentrations of carp were therefore directly influenced by their feeding behavior and correlated negatively with increasing dietary proportions of supplemented fish feeds. In contrast, supplementary VO feeds contributed generally less to the carp diet, but carp exposed to VO feeds contained highest MeHg concentrations. This demonstrates that pond zooplankton, but not supplementary feeds, was the main vector for MeHg bioaccumulation of carp and possibly even other fish raised in semi-intensive aquaculture.

Differences in dietary proportions of supplementary fish feeds (VO vs. FO) were unexpected as the fish equally initiated the supply of all additional feeds. Clearly, the higher quality of supplementary compound feeds directly affected the feeding behavior of carp (higher demand for FO diets) and therefore MeHg concentrations of carp muscle tissues. The contribution of supplied feeds to the diet of carp did not differ among K1- and K2-carp and FO diets were generally assimilated to a large extent (46.1–76.5%). The much lower proportion of ingested VO diets (9.8–22.9%) resulted in a higher amount of zooplankton food for carp exposed to VO diets. Regression analyses revealed that increasing dietary proportion of supplementary, high-quality diets resulted in lower MeHg concentrations in carp and predicted 42% of the MeHg variability of carp. Seasonal variation of MeHg concentrations in zooplankton and/or growth dilution effects may have reduced the predictive power of food source use with respect to MeHg bioaccumulation in carp for the current study.

The correlation coefficient may have been lowered by strong variability of MeHg concentrations in zooplankton between the different seasons and ponds. Although carp exposed to FO feeds used a much higher proportion of this supplemented diet source, they concurrently fed to various degrees upon zooplankton. Therefore, MeHg concentrations of carp muscle tissues reflected an integrated value of zooplankton-derived MeHg consumed over the entire growing season in the fish of all ponds. In addition to naturally varying MeHg concentrations among different aquatic systems, it was demonstrated that zooplankton shows a strong seasonal variation of MeHg concentrations with lowest concentrations in spring, peaking MeHg during mid summer and slightly decreased concentrations in late summer (Garcia et al., 2007; Kainz et al., 2006). Although such clear seasonal variations were not found in this study, MeHg concentrations of zooplankton differed among ponds and between summer and fall. Although MeHg concentrations in carp represent a time integrated value of MeHg bioaccumulation, the proportion of supplementary feeds consumed by carp still correlates negatively with their MeHg concentrations, emphasizing the high importance of diet source quality on MeHg bioaccumulation of carp.

As the bioaccumulation of MeHg is a function of body size, weight, and age of an organism (Kainz et al., 2006; McIntyre and Beauchamp, 2007), enhanced somatic growth, in particular of the K2-carp of the FO ponds, may have suppressed the dietary effect of zooplankton-derived MeHg in these carp. It needs to be noticed that MeHg concentrations of the zooplankton in FO ponds were clearly higher than in other ponds. Although feeding on relatively less zooplankton, dietary contribution of zooplankton-derived MeHg to carp of the FO ponds might have reached similar MeHg concentrations compared to carp of the VO and reference ponds, the latter feeding on a higher zooplankton proportion, yet lower zooplankton-derived MeHg concentrations. MeHg concentrations did not differ significantly between K1- and K2-carp, however, the K2-carp of FO ponds had significantly higher body weights than the carp of VO ponds, which strongly suggests that the low MeHg concentrations may have also been caused, in part, by growth dilution in these ponds receiving high quality diets. Such diet quality related effect is likely because the K2-carp of pond VO1 had the highest MeHg concentrations, yet the lowest body weight of all ponds. Thus, finding the lowest MeHg concentrations and highest body weight/length in K2-carp of ponds supplied with FO diets emphasizes the importance of high diet quality on lowering MeHg concentrations per unit biomass. We relate such beneficial effects to dietary fish oils that are, compared to vegetable oils, rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), in particular long chain omega-3 PUFA (Olsen, 1999). Even if weakly lipophilic and not directly related to fatty acids (Kainz and Fisk, 2009), MeHg concentrations may be directly influenced by omega-3 PUFA rich diets (FO diets) as these generally support the somatic growth of fish (Copeman et al., 2002; Tocher, 2003). Therefore, modulating the effect of growth dilution, feeds of biochemically high quality potentially lead to considerable reductions of total MeHg concentrations in farm-raised fish, yet provide increased fish yields.

This study has shown that carp preferably ingest and retain high quality diet sources. This important diet fish clearly preferred feeding on supplementary compound feeds (up to 76.5%) over zooplankton, suggesting that these feeds contain highly suitable dietary compounds that carp require for their physiological development. The FO diet selection resulted in lower MeHg bioaccumulation in carp because this preferentially obtained diet contained, per unit biomass, less MeHg than zooplankton. These results suggest that carp, and perhaps also other farm-raised freshwater fish, can reduce their MeHg bioaccumulation by selective feeding on biochemically high quality diet sources that subsequently support somatic growth and fish health (Arts and Kohler, 2009). However, we stress that such high quality feeds should be derived from either autochthonous or other environmentally sustainable sources and not from marine sources. Identifying such sustainable high quality food sources without MeHg or other contaminants for diet fish still remains a scientific challenge for the near future.

Author contributions

SS and MJK designed the research. SS, BV and MJK performed the research, data analysis, and wrote the paper. SS and BV contributed new reagents/analytical tools.

Acknowledgments

We thank Z. Changizi-Magrhoor and J. Watzke (WasserCluster Lunz), M. Watzka (University of Vienna), and S. Chen (University of Québec at Montréal, Canada) for analytical support, Teichwirtschaft Waldviertelfisch for logistical help and feeding, and GarantTiernahrung™ (Pöchlarn; Austria) for providing marine compound feeds. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF project L516-B17) to MJK. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Contributor Information

Sebastian Schultz, Email: Sebastian.schultz@wkl.ac.at.

Birgit Vallant, Email: Birgit.Vallant@umweltbundesamt.at.

Martin J. Kainz, Email: martin.kainz@donau-uni.ac.at.

References

- Arts M.T., Kohler C.C. Health and condition of fish: the influence of lipids on membrane competency and immune response. In: Arts M.T., Brett M.T., Kainz M.J., editors. Lipids in Aquatic Ecosystems. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 237–255. [Google Scholar]

- Arts M.T., Ackman R.G., Holub B.J. “Essential fatty acids” in aquatic ecosystems: a crucial link between diet and human health and evolution. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2001;58(1):122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Berntssen M.H.G., Julshamn K., Lundebye A.-K. Chemical contaminants in aquafeeds and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) following the use of traditional- versus alternative feed ingredients. Chemosphere. 2010;78(6):637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K.C., Leung H.M., Wong M.H. Metal concentrations of common freshwater and marine fish from the Pearl River Delta, South China. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2008;54(4):705–715. doi: 10.1007/s00244-007-9064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson T.W. The three modern faces of mercury. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110(1):11–23. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeman L.A., Parrish C.C., Brown J.A., Harel M. Effects of docosahexaenoic, eicosapentaenoic, and arachidonic acids on the early growth, survival, lipid composition and pigmentation of yellowtail flounder (Limanda ferruginea): a live food enrichment experiment. Aquaculture. 2002;210(1–4):285–304. [Google Scholar]

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations World aquaculture production of fish, crustaceans, molluscs, etc., by principal species in 2008. FAO Rome. 2008. http://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/global-aquaculture-production/en [online] Available from. [accessed 25 August 2011]

- Foran J.A., Hites R.A., Carpenter D.O., Hamilton M.C., Mathews-Amos A., Schwager S.J. Vol. 23. Wiley Periodicals, Inc; 2004. pp. 2108–2110. (A survey of metals in tissues of farmed Atlantic and wild Pacific salmon). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia E., Carignan R., Lean D. Seasonal and inter-annual variations in methyl mercury concentrations in zooplankton from boreal lakes impacted by deforestation or natural forest fires. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2007;131(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10661-006-9442-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göttlicher S., Knohl A., Wanek W., Buchmann N., Richter A. Short-term changes in carbon isotope composition of soluble carbohydrates and starch: from canopy leaves to the root system. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2006;20(4):653–660. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guallar E., Sanz-Gallardo M.I., Van't Veer P., Bode P., Aro A., Gomez-Aracena J., D. Karl J.D., Riemersma R.A., Martin-Moreno J.M., Kok F.J. Mercury, fish oils, and the risk of myocardial infarction. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:1747–1754. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kainz M.J., Fisk A.T. Integrating lipids and contaminants in aquatic ecology and ecotoxicology. In: Arts M.T., Brett M.T., Kainz M.J., editors. Lipids in Aquatic Ecosystems. Springer; Berlin: 2009. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kainz M., Telmer K., Mazumder A. Bioaccumulation patterns of methyl mercury and essential fatty acids in lacustrine planktonic food webs and fish. Science of the Total Environment. 2006;368(1):271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kainz M., Arts M.T., Mazumder A. Essential versus potentially toxic dietary substances: a seasonal comparison of essential fatty acids and methyl mercury concentrations in the planktonic food web. Environmental Pollution. 2008;155(2):262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiljunen M., Grey J., Sinisalo T., Harrod C., Immonen H., Jones R.I. A revised model for lipid-normalizing δ13C values from aquatic organisms, with implications for isotope mixing models. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2006;43(6):1213–1222. [Google Scholar]

- McConnaughey T., McRoy C.P. Food-web structure and the fractionation of carbon isotopes in the Bering Sea. Marine Biology. 1979;53(3):257–262. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchan J.H., Jr., Lewis W.M., Jr., Kendall C., McGrath C.C. Variation in trophic shift for stable isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. Oikos. 2003;102(2):378–390. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre J.K., Beauchamp D.A. Age and trophic position dominate bioaccumulation of mercury and organochlorines in the food web of Lake Washington. Science of the Total Environment. 2007;372(2–3):571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muus B.J., Dahlström P. Vol. 8. Auflage — BLV Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; München, Wien, Zürich: 1998. (Süßwasserfische Europas — Biologie, Fang, wirtschaftliche Bedeutung). [Google Scholar]

- Olsen Y. Lipids and essential fatty acids in aquatic food webs: what can freshwater ecologists learn from mariculture? In: Arts M.T., Wainman B.C., editors. Lipids in Freshwater Ecosystems. Springer; New York: 1999. pp. 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B.J., Fry B. Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1987;18:293–320. [Google Scholar]

- Pichet P., Morrison K., Rheault I., Tremblay A. Analysis of total mercury and methyl mercury in environmental samples. In: Lucotte M., Schetagne R., Thérien N., Langlois C., Tremblay A., editors. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 1999. pp. 41–52. (Mercury in the Biogeochemical Cycle, Natural Environments and Hydroelectric Reservoirs of Northern Québec). [Google Scholar]

- Power M., Klein G.M., Guiguer K.R.R.A., Kwan M.K.H. Mercury accumulation in the fish community of a sub-Arctic lake in relation to trophic position and carbon sources. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2002;39:819–830. [Google Scholar]

- Schlott K. Die planktische Naturnahrung und ihre Bedeutung für die Fischproduktion in Karpfenteichen. Schriftenreihe des Bundesamtes für Wasserwirtschaft. 2007;27:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens W., Wirth M. Influence of nutrition on the lipid quality of pond fish: common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and tench (Tinca tinca) Aquaculture International. 2007;15(3–4):313–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting C.J., Barry J.T., Polunin N.V.C., Jennings S. Effects of body size and environment on diet-tissue δ13C fractionation in fishes. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2007;352(1):165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Tocher D.R. Metabolism and functions of lipids and fatty acids in teleost fish. Reviews in Fisheries Science. 2003;11(2):107–184. [Google Scholar]

- Turchini G.M., Torstensen B.E., Ng W.-K. Fish oil replacement in finfish nutrition. Reviews in Aquaculture. 2009;1(1):10–57. [Google Scholar]

- Valente L.M.P., Cornet J., Donnay-Moreno C., Gouygou J.P., Bergé J.P., Bacelar M., Escórcio C., Rocha E., Malhão F., Cardinal M. Quality differences of gilthead sea bream from distinct production systems in Southern Europe: intensive, integrated, semi-intensive or extensive systems. Food Control. 2011;22(5):708–717. [Google Scholar]

- Vallant B., Kadnar R., Goessler W. Development of a new HPLC method for the determination of inorganic and methyl mercury in biological samples with ICP-MS detection. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry. 2007;22:322–325. [Google Scholar]

- Vander Zanden M.J., Rasmussen J.B. A trophic position model of pelagic food webs: impact on contaminant bioaccumulation in lake trout. Ecological Monographs. 1996;66(4):451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Watzka M., Buchgraber K., Wanek W. Natural 15N abundance of plants and soils under different management practices in a montane grassland. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2006;38(7):1564–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Tocher D.R., Dickson C.A., Bell J.G., Teale A.J. Highly unsaturated fatty acid synthesis in vertebrates: new insights with the cloning and characterization of a Δ6 desaturase of Atlantic salmon. Lipids. 2005;40(1):13–24. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]