Abstract

Anthropogenic 236U (t½=23.4 My) is an emerging isotopic ocean tracer with interesting oceanographic properties, but only with recent advances in accelerator mass spectrometry techniques is it now possible to detect the levels from global fall-out of nuclear weapons testing across the water column. To make full use of this tracer, an assessment of its input into the ocean over the past decades is required. We captured the bomb-pulse of 236U in an annually resolved coral core record from the Caribbean Sea. We thereby establish a concept which gives 236U great advantage – the presence of reliable, well-resolved chronological archives. This allows studies of not only the present distribution pattern, but gives access to the temporal evolution of 236U in ocean waters over the past decades.

Keywords: oceanic tracer, 236U, coral, accelerator mass spectrometry, fallout

Highlights

► This is the first ever annually-resolved record of 236U from global fall-out. ► We demonstrate the usefulness of 236U as oceanic tracer using coral cores. ► Using the record a value for the total global fall-out of 236U has been determined.

1. Introduction

Thermo-nuclear weapons of the fission–fusion–fission type (“Teller–Ulam design”) produce 236U via neutron capture on 235U and (n,3n) on 238U in the final stage, when the fast neutrons from the fusion are employed to fission uranium in the so-called tamper. The anthropogenic input of 236U is significantly larger than the ambient natural 236U expected from cosmogenic and nucleogenic production (Sakaguchi et al., 2009; Steier et al., 2008).

Uranium has an oceanic residence time of 0.3–0.5 million years (Bloch, 1980; Dunk et al., 2002) – due to the uranyl carbonate ion which forms under oxic conditions – and strongly correlates to salinity (Chen et al., 1986; Pates and Muir, 2007). This is the basis of the conservative behavior of uranium in the oceans and a good basis for using 236U as an oceanic tracer.

Although in terms of abundance 236U is one of the most prominent anthropogenic radionuclides dispersed by nuclear weapons testing until recently it has eluded detection from this source (Sakaguchi et al., 2009). 236U has been measured routinely for nuclear safeguards and national security applications (Boulyga et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2004; M. Hotchkis et al., 2000a; M.A.C. Hotchkis et al., 2000b; Ketterer et al., 2003), but only with significant advances in the techniques of measurement (Berkovits et al., 2000; Fifield, 2008; Paul et al., 2000; Purser et al., 1996; Steier et al., 2010; Vockenhuber et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 1997, 1994) has it been possible to conduct first studies on global fall-out 236U in ocean water samples (Christl et al., 2012; Sakaguchi et al., 2012).

What makes 236U particularly interesting as oceanic tracer is the existence of reliable geological archives in the form of coral cores: since corals build uranium into their aragonite skeleton at a level of 2–4 ppm by substitution of uranium for calcium in the lattice, they are an ideal archive to trace the input of 236U by nuclear testing and further 236U evolution in the ocean. In this study we have applied this principle to the study of the input and evolution of bomb-pulse 236U in the oceans.

2. Samples and methods

2.1. The HMF-1 coral core

The coral core labeled HMF-1 (species Montastraea faveolata) was sampled at a depth of 6 m on the fore-reef off the eastern coast of Turneffe Atoll, Belize (17°18′25″N, 87°48′04″W) in the Caribbean Sea. It was taken in 2006, and has been previously analyzed for trace elements (Carilli et al., 2009b). The coral core revealed a well-defined annual banding structure by X-ray and stretches back more than 100 years (Fig. 1). The stratigraphy has been cross-dated with other cores from the region using standard dendrochronological methods (Fritts, 1976; Carilli et al., 2010). We sub-sampled on a year-by-year basis from 1944 to 2006, but took multiyear samples for the pre-nuclear period in order to improve the detection limit, which depends on the sample mass of uranium.

Fig. 1.

The coral core HMF-1 under X-ray: a well-defined stratigraphy going back 100 years. The prominent dense double band in the piece in the upper left corner marks the years 1998 and 1999, when the colony was stressed by both exceptionally high sea surface temperatures (due to the 1998 El Nino) and Hurricane Mitch (Carilli et al., 2009a).

2.2. Sample preparation

Based on the X-ray image, one half-core was sliced year by year along the approximate banding structure, with typical slices weighing 4 g. Samples were cleaned mechanically and followed by several ultrasonic cleaning steps, including one in a 1:1 mixture of 30% H2O2 and 1% NaOH to hydrolyze organics, followed by an ultrasonic bath in 0.15 M HNO3 to remove potential surface contaminants (∼10% material loss). For 4 samples this cleaning solution was preserved and analyzed for 236U/238U. Results are in agreement within statistics with those from the cleaned bulk.

For uranium extraction, the cleaned CaCO3 was disolved in HCl (suprapur, previously passed through an UTEVA column) after adding 233U spike (IRMM-58 in-house diluted, 1.12·109 atoms of 233U for each sample). 2–3 mg of iron carrier was added and U coprecipitated with iron hydroxide. The iron carriers used were Goodfellow 99.99+% high purity iron for most of the samples and later in the project a p.a. iron reagent (Merck) supposedly from the pre-nuclear era was tested, with the same result for blank levels.

The precipitate was redisolved in 3 M HNO3 and loaded onto an in-house prepared UTEVA column. Elution steps of 3 M HNO3, 9 M HCl, and 5 M HCl with 0.05 M oxalic acid separated uranium from contaminants. U was eluted with 0.2 M HCl. 3 mg of iron carrier was added and once again precipitated. The iron hydroxide matrix was oxidized in air (900 °C) and pressed into sputter cathodes for AMS analysis.

Several procedural blanks were prepared. Also, since there was sample material from before 1945, we had effectively full chemistry blanks as well. Typically, 1–2 counts per hour were seen on the procedural blank targets with targets lasting between 3–5 h. This seems to be independent of the total amount of uranium in the targets (for details see Supplementary Fig. S1). For the older part of the core, several years were sampled together in order to increase the amount of U per sample and thus improve the detection limit.

2.3. AMS measurements of 236U

The AMS measurements were carried out at the Vienna Environmental Research Accelerator (VERA). In AMS, the interference of molecules is removed by selecting a sufficiently high charge state (5+ in the case of the 236U measurements) which does not allow for stable molecules. Highly-resolving electrostatic and magnetostatic analyzers are combined to deal with potentially interfering products from molecular break-up. At VERA the low energy side consists of an electrostatic analyzer and a bending magnet.(Steier et al., 2010) The high energy side comprises a Wien Filter, the main analyzing magnet, a high resolution electrostatic analyzer (specifically added to the setup for heavy ion AMS), and a switching magnet. A time-of-flight (ToF) spectrometer is available for reliable particle identification followed by a Bragg-type ionization chamber.(Steier et al., 2010) For the measurements presented, the ToF was only used on a few samples for checking that there is no non-236U background in the 236U bin of the Bragg detector spectrum. Results from measurements from the same sample with and without the ToF agreed within uncertainties. Therefore, the use of the ToF detector, which in our present setup lowers the overall efficiency by a factor of 5, was omitted for most of the measurements presented. The measurements using the ToF are still valuable in that they confirm that the seen blank levels are actual 236U counts (from picked up ambient 236U) and not machine background from other scattered ion species.

The total record is the combined result of several measurement series with some samples carried over for quality control purposes. Several hours of measurement on each sample were required to accumulate significant statistics. The results given in this paper are blank-corrected using the overall blank value from procedural blanks. For this correction, the average number of blank 236U counts per 233U spike count on the procedural blanks was used.

The measurement is relative to our Vienna-KkU standard which has been determined to (6.98±0.32)×10−11, as a result of an intercomparison (Steier et al., 2010). Reproducibility was tested for two categories: (a) inter beam-time reproducibility by carrying over already measured samples to other beam-times and (b) sampling and preparation reproducibility by duplicates separately sampled from the other halves or overlapping sections of the core. We find reduced Chi-squares of 1.50 (for 12 cathodes carried over), and 1.20 (for 8 pairs of samples) for these categories, respectively. The Chi-square for inter beam-time variability would point to a contribution to uncertainty of about 6% independent of counting statistics. The Chi-square for sampling and preparation still has a 29% probability of being random chance.

The uncertainties we give for the 236U/238U ratios are the combined result of counting statistics on the sample and on the standard, inter-run scatter of the samples and the standard, and the blank correction.

3. Results and discussion

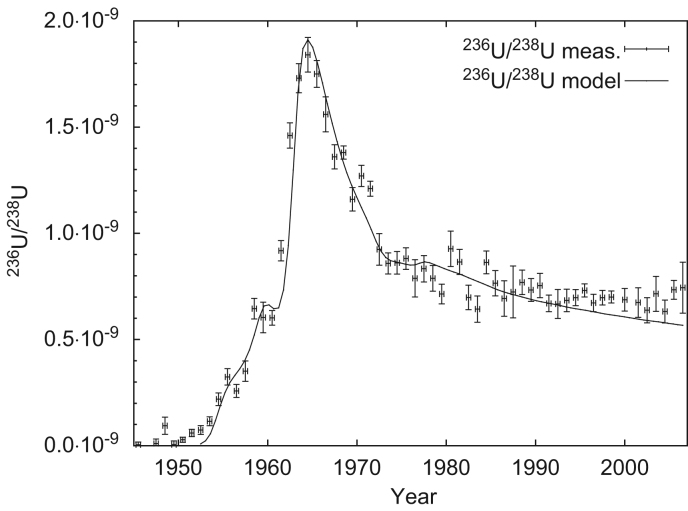

In the coral core record, we see an increase of 236U from 1953 to 1963, a sharp drop from 1964 to 1972, followed by a relatively slow decline until today (Fig. 2). The shape of the record can be explained by three main effects, which work simultaneously at all times, but each of them dominating the qualitative picture for a certain period: (1) the input of 236U by the global stratospheric fall-out from bomb-testing which is mostly responsible for the features during the increasing time period; (2) the drop from 1964 to 1972 is dominated by transport of southern hemispheric surface water into the Caribbean, displacing water masses exposed to the more intense northern hemispheric fall-out; and (3) 236U is transported to greater depth by turbulent diffusion.

Fig. 2.

The 236U/238U record from the HMF-1 coral core compared to our simple model: the 236U/238U data is shown with associated error bars for the isotope ratio (1σ) and the timing uncertainty for the coral slices (total range estimate); the model is shown as a black line interpolated between the calculated points.

From the pre-nuclear test (earlier than 1945) samples we can give a conservative experimental upper limit of 4×10−12 for the pre-anthropogenic level of the 236U/238U isotopic ratio in ocean water (Table 1). This still represents a detection limit, though, since the actual pre-anthropogenic level is expected to be in the 10−13 to 10−14 range.

Table 1.

236U/238U ratios for large pre-nuclear age samples.

| Coral years | Dry mass | 236U/238U (×10−12) | Corresponding blank value (×10−12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (g) | |||

| 1905–1911 | 71 | 3.3±0.6 | 2.8±1.6 |

| 1929–1938 | 63 | 5.2±1.5 | 3.7±2.1 |

| 1939–1943 | 37 | 8.0±2.3 | 4.4±2.5 |

The 236U/238U values shown are not corrected for chemistry procedural blank levels. The 4th column shows the corresponding blank level value, which is undistinguishable from the measured values for these samples. 1σ-errors are given.

3.1. Modeling the 236U record

Unlike tracers distributed in gaseous form (e.g. Chloro-Fluoro-Carbons, 14C) 236U has a strong local variation in fall-out intensity and oceanic uptake. While this complicates the picture in interpreting the data, it also offers opportunities, particularly helping to estimate water mass transfer between northern and southern hemisphere.

With regard to fall-out function, we expect that the situation is comparable with 137Cs, except for the presence of additional contributions to 137Cs from fission device fall-out.

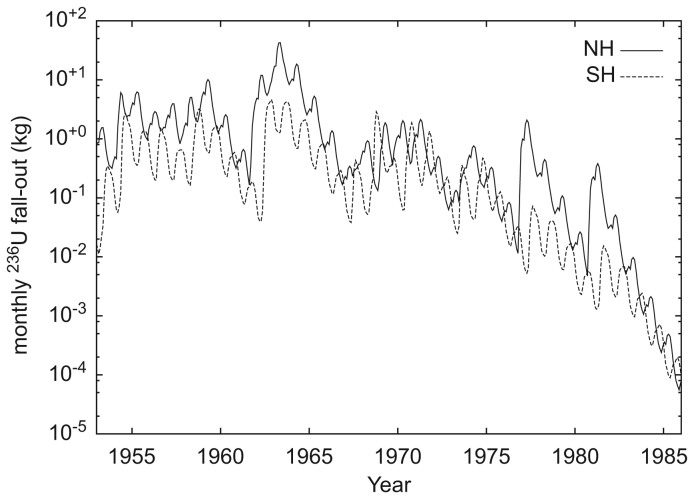

The global fall-out function (Fig. 3) was calculated by adapting the semi-empirical model of the 2000 UNSCEAR report (UNSCEAR, 2000). Only a subset of nuclear tests contribute to the production of globally dispersed 236U: thermonuclear devices that display high fission yields from the uranium tamper by neutrons from the fusion stage. In absence of better information, the fission yield (in Mt TNT equivalent) of these devices can be used as a proxy for the 236U production. The fission yield of these devices stems almost exclusively from the fission of the uranium tamper by the neutrons released from the fusion last stage. These are the same key ingredients as for the production of 236U although the relative efficiency for fission versus 236U production may still vary depending on design.

Fig. 3.

Global stratospheric 236U fall-out in kg/month. Northern (solid) and southern (dashed) hemispheric fall-out from testing of thermonuclear devices are shown separately. This is a new version of the model presented in the UNSCEAR (2000) report, adapted to gauge 236U production from these tests. The initial output of the model is actually in terms kt TNT equivalent fission yield, which has been converted to kg of 236U using our conversion factor (7.4 kg per Mt TNT equivalent) derived from the 236U/238U ratios in the coral core record. The fall-out model indicates that by the end of 1964 more than 80% of all bomb-produced 236U had already been deposited on the earth's surface.

From Table 1 of the Annex C of the 2000 UNSCEAR report we obtain a fission yield of 143 Mt TNT equivalent injected into the stratosphere by these devices. The fall-out model indicates that by the end of 1964 more than 80% of all bomb-produced 236U had already been deposited on the earth's surface. Such a spike, if confirmed, could also be a useful time marker for dating purposes.

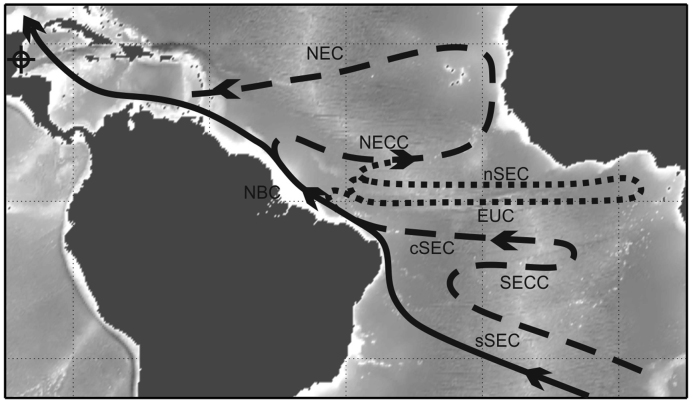

The water masses in the Caribbean from which our coral precipitated the uranium into its aragonite skeleton predominantly originate from the southern hemisphere, transported via the Southern Equatorial Current (SEC), the North Brazil Current (NBC), and the Antilles Current (AC) to the Caribbean Sea (Fig. 4). Fall-out in the southern hemisphere is significantly lower in intensity than in the northern hemisphere. This means that only in the period of on-going tests (1952 to 1963) is there a strong contribution of northern hemispheric fall-out, which was introduced after the water masses had already arrived north of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The fall-out intensity declines from peak fall-out with a time constant of ∼8 months (as can be discerned from Fig. 3), if seasonal effects are removed, which is of the same order as the average travel (10 months) of Caribbean current eddies from the Lesser Antilles to the Yucatan as suggested by (Murphy et al., 1999). After the atmospheric test ban was implemented, the effect of on-going northern hemispheric addition becomes negligible and over time the 236U/238U ratio changes to southern hemisphere levels, by 236U transported by ocean currents.

Fig. 4.

Surface currents of the South Atlantic and the location of coral core HMF-1. Shown are the approximate locations of the South Equatorial Current (SEC) with the southern (sSEC), central (cSEC), and northern (nSEC) branch; the South Equatorial Counter Current (SECC); the Equatorial Undercurrent (EUC); the North Equatorial Counter Current (NECC); the north equatorial current (NEC) and the North Brazil Current (NBC).(Stramma and Schott, 1999) The cross-hair marks the location of our coral core. The solid line marks the shortest plausible trajectory from the central South Atlantic to the Caribbean Sea.

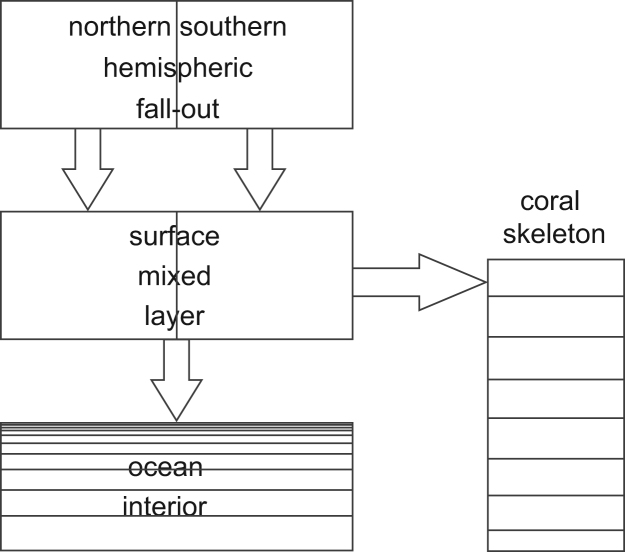

To take into account the dynamics of the ocean transport combined with the location dependency of fall-out, we model a water body which stretches from the southern hemisphere to the sampling site, and moves at a constant speed (advection-only) in that direction (for details see Appendix A and Fig. 5). The water body is topped by a mixed layer of 100 m, and Fickian diffusion is assumed for vertical transport. The chosen mixed layer depth corresponds to the layer of water which has been in contact with the surface at some point over the course of one year looking back (de Boyer Montégut et al., 2004; Guilyardi et al., 2001).

Fig. 5.

Sketch of the model depicting the flux of 236U between the boxes. The fall-out is separated into a Caribbean (“northern”) and a south Atlantic (“southern”) fall-out which accumulates in the mixed layer until the water arrives at the location of our coral core. During transit from the south Atlantic to the coral core some 236U is lost to the ocean interior due to diffusion.

A location-dependent fall-out intensity (fall-out per unit area) modifier accounts for the latitude and rainfall dependence of the fall-out in our model. In absence of specific data on 236U, we anchor the fall-out intensity over the South Atlantic to available 137Cs data and models of 137Cs fall-out (Aoyama et al., 2006). A ratio of 0.36 of South Atlantic fall-out intensity to global average (stratospheric) fall-out intensity is assumed in the model. Over the South Atlantic both 137Cs and 236U can be expected to be entirely from thermo-nuclear devices, however in the total fall-out over the planet we have to discount the contribution (a 8% correction) from fission devices to relate 137Cs to 236U.

The ratio between Caribbean fall-out intensity to the northern hemispheric average was assumed as 0.57 for best fit, giving a ratio of 2.58 between the Caribbean and the South Atlantic end-member. The Aoyama evaluation of 137Cs data (Aoyama et al., 2006) suggests a significantly higher value for the latter number, a ratio of 9 if the grid value closest to the location of our core is selected. However, the Caribbean end-member would then depend on one grid value in a rather coarse grid. Averaging over the next neighbors for this grid point yields a factor of 3.6 between the Caribbean and South Atlantic fall-out intensities, which is close to our adjusted value.

Corals do not build their skeleton only on their outmost surface, but aragonite formation is rather spread over the full thickness of the still living organic layer (Barnes and Lough, 1993). In our model, we accounted for that with an averaged 6 month time-lag: a triangular distribution peaking at 12 months was used to represent each coral year. This is in line with an estimate of the organics layer at the top of the core and gives a good fit to the data. Due to the size of the coral pieces required (4 g), there is also an uncertainty associated with the slicing of our sample. We do not expect this to exceed 3 months.

3.2. The input of 236U into the ocean

The features of the modeled fall-out function are reflected in our 236U/238U record: The so-called moratorium period from autumn 1958 to autumn 1961 shows up as a hiatus in the increase of 236U from coral years 1958 to 1960. 236U has a typical atmospheric residence time of up to one year, depending on season and the location of the specific test. Our fall-out model for 236U and the coral record are in good agreement regarding the atmospheric residence time.

Using our model, we can also obtain the amount of 236U dispersed globally by nuclear weapons testing from the coral data. The contribution the HMF-1 core sees from local fall-out of 236U is negligible. Thus we assume exclusively stratospheric fall-out and find a production of 7.4±1.6 kg 236U per Megaton TNT fission yield of a thermo-nuclear device. This translates to a global dispersion of 1060 kg 236U as stratospheric fall-out. In addition, we expect a rather significant local contribution of about 240 kg to the equatorial Pacific by US testing. This input should be visible in coral cores of the region and may also show up in oceanic 236U concentrations.

The conversion of test yields in kt to kilograms of 236U emerges naturally via the amplitude from fitting the model curve to the measured 236U/238U ratios over the years 1952 to 1980. For the assumption about the effective mixed layer depth, we assume an uncertainty (∼15%) which directly affects the yield-to-fallout conversion factor and thus the estimated total fall-out. The other main contribution to the uncertainty comes from the spatial fallout intensity modulator. From the 137Cs data of Aoyama et al. (2006) we can estimate this contribution to be 15% as well. As these two are independent the total uncertainty from these factors is 22%.

Our determination of the total 236U fall-out is in agreement with the estimate of 900 kg by Sakaguchi et al. (2009), which was derived from measured 236U/239Pu ratios of global fall-out in soil samples, and somewhat lower than the estimate of 2100 kg by Christl et al. (2012) based on two 236U profiles from the equatorial Atlantic.

3.3. Evolution of 236U in the ocean

From the first, steeper decline after the bomb-pulse we can derive the effective time of transit from the ITCZ to the Caribbean. Our simple model fits best with an effective transit time of 10 yr. It is difficult to obtain this result from average water velocities, because the real flow pattern is more complex, particularly because of recirculation due to the North Equatorial Counter Current (NECC) and the Equatorial Undercurrent (EUC). An assumed single trajectory from the Angola Basin via the SEC, and the NBC to Turneffe atoll in the Caribbean Sea has a path length of 1.2×107 m (Fig. 4). That would make the typical net velocity 0.04 m/s, but up to 0.06 m/s if the additional path due to recirculation via the NECC/EUC is considered. The OSCAR (NOAA, 2012) long-term average suggests an average of 0.20 m/s for the East to West transport in the SEC, and about the same for the NBC and the AC. However, these velocities do not represent the average velocity of the mixed layer. The Stramma and England evaluation (Stramma and England, 1999) of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment suggests a somewhat lower velocity (∼0.05 m/s) and different vectors at 90 m depth for the region of the SEC. The discrepancies between our estimated numbers and data from current meters are not atypical for tracer studies. (Waugh and Hall, 2005) Given that our simple model does not consider lateral mixing and diffusion, the transit time estimated from the coral core is roughly in agreement with these mean velocities.

The vertical diffusion coefficient dominates the decrease of the 236U level after ca. 1973, which is surprisingly slow. If diffusion really is the only effective process, the corresponding diffusion coefficient would be ∼0.1 cm2/s. While this is reasonable for open ocean isopycnal diffusivities, it is interesting that the basin-wide effective transport of water masses to depth is that slow. An alternative explanation, not taken into account by our simple model, could be leakage of northern hemispheric waters into the South Atlantic via the Agulhas Current, which has been suggested based on 137Cs observations in South Atlantic surface waters (Aoyama et al., 2011; Sanchez-Cabeza et al., 2011; Tsumune et al., 2011). This effect would take some decades to be seen, since the fall-out over the Indian Ocean is not much higher than the fall-out over the South Atlantic and the transit time from the Pacific via the Indian Ocean is roughly two decades (Aoyama et al., 2011; Sanchez-Cabeza et al., 2011; Tsumune et al., 2011). Since this is not taken into account in our model and could explain deviation from the measured 236U/238U ratio from 1995 onwards. The most recent levels of 236U found in the coral agree with the result of Christl et al. (2012) for a surface ocean water sample from the equatorial Atlantic (2°5′45.127″N, 41°7′0.307″W, corresponding to the nSEC) collected in 2010 by the GEOTRACES (2011) cruise PE321, but is significantly below surface water samples from the northern hemisphere (Eigl et al., 2012, 2011; Sakaguchi et al., 2012).

The case regarding coral records that can be made for 236U also applies to 90Sr and some studies on coral records of this isotope have been published (Benninger and Dodge, 1986; Purdy et al., 1989; Toggweiler and Trumbore, 1985). This makes it an interesting isotope to compare with given its present level also originates from nuclear testing, although the 90Sr will also have a contribution from fission-only devices. Therefore such records are also more likely to be affected by local fall-out from low-yield devices if they are located near test-sites.

The study by Toggweiler and Trumbore includes several coral records from locations in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. The record of a coral core from Oahu, an unambiguously northern hemispheric location, shows a pronounced fall-out peak for the band centring on the year 1964 and a subsequent fall (similar to our 236U record) in the 90Sr levels until 1979, where the record ends. This is compared with records from the equatorial and southern hemispheric records, which stay flat (perhaps rise slightly) after the peak fall-out. Toggweiler and Trumbmore interpret this as the result of inter-gyre exchange between the relevant Pacific current systems. This is similar to our argument for the shape of our record after the fall-out peak, which is based on the pronounced cross-equatorial western boundary current in the Atlantic.

4. Conclusions

Using our cutting-edge heavy isotope AMS-system we measured the first ever yearly resolved coral record for 236U from bomb-fallout. From this record we could confirm that this fall-out on a global scale follows a model adapted from existing models for other isotopes. Applying these models we have determined the total fall-out of 236U to 1300 kg (with an estimated uncertainty of 20%) of which we attribute 1060 kg to the global stratospheric fall-out.

We could exploit the differential between northern and southern hemispheric fall-out to extract a transit time estimate from the core, demonstrating the use of 236U as a tracer for ocean water. This principle could be applied to coral cores from other suitable locations. The anticipated large local contribution in the Pacific and the availability of suitable corals could be another interesting opportunity for this tracer Table 2.

Table 2.

236U/238U data for coral core HMF-1.

| Sample | Coral year | Dry mass | 236U/238U (×10−9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (g) | |||

| HMF-1-1944B4 | 1944 | 3.33 | <0.01 |

| HMF-1-1945B4 | 1945 | 2.35 | <0.02 |

| HMF-1-1946B4 | 1946 | 1.45 | <0.03 |

| HMF-1-1947B4 | 1947 | 1.28 | <0.04 |

| HMF-1-1948B4 | 1948 | 1.31 | 0.09±0.04 |

| HMF-1-1949B3 | 1949 | 2.24 | <0.03 |

| HMF-1-1950B3 | 1950 | 3.74 | 0.03±0.01 |

| HMF-1-1951B3 | 1951 | 3.89 | 0.06±0.02 |

| HMF-1-1952B3 | 1952 | 3.69 | 0.07±0.02 |

| HMF-1-1953B3 | 1953 | 3.93 | 0.12±0.02 |

| HMF-1-1954B3 | 1954 | 4.30 | 0.22±0.03 |

| HMF-1-1955B3 | 1955 | 3.36 | 0.32±0.04 |

| HMF-1-1956B3 | 1956 | 3.32 | 0.26±0.03 |

| HMF-1-1957B3 | 1957 | 3.98 | 0.35±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1958B3 | 1958 | 3.35 | 0.65±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1959B3 | 1959 | 3.31 | 0.60±0.07 |

| HMF-1-1960B3 | 1960 | 3.85 | 0.60±0.03 |

| HMF-1-1961B3 | 1961 | 4.14 | 0.92±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1962B3 | 1962 | 4.12 | 1.46±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1963B2 | 1963 | 2.38 | 1.73±0.07 |

| HMF-1-1964B3 | 1964 | 2.06 | 1.84±0.08 |

| HMF-1-1965B2 | 1965 | 5.21 | 1.75±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1966B2 | 1966 | 3.75 | 1.56±0.08 |

| HMF-1-1967B2 | 1967 | 4.85 | 1.36±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1968B2 | 1968 | 4.48 | 1.38±0.03 |

| HMF-1-1969B2 | 1969 | 3.20 | 1.16±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1970B2 | 1970 | 3.98 | 1.27±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1971B2 | 1971 | 4.10 | 1.21±0.04 |

| HMF-1-1972B2 | 1972 | 4.99 | 0.92±0.07 |

| HMF-1-1973B2 | 1973 | 5.14 | 0.86±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1974B2 | 1974 | 4.59 | 0.86±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1975B2 | 1975 | 4.86 | 0.88±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1976B2 | 1976 | 5.23 | 0.79±0.09 |

| HMF-1-1977B2 | 1977 | 4.24 | 0.83±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1978B2 | 1978 | 3.47 | 0.79±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1979B2 | 1979 | 3.96 | 0.71±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1980B2 | 1980 | 4.38 | 0.93±0.08 |

| HMF-1-1981B2 | 1981 | 2.85 | 0.87±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1982B2 | 1982 | 5.83 | 0.70±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1983B2 | 1983 | 5.63 | 0.64±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1984B2 | 1984 | 4.60 | 0.86±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1985B2 | 1985 | 4.12 | 0.77±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1986B2 | 1986 | 3.03 | 0.69±0.08 |

| HMF-1-1987B2 | 1987 | 3.85 | 0.72±0.12 |

| HMF-1-1988B2 | 1988 | 4.57 | 0.77±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1989B2 | 1989 | 3.76 | 0.73±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1990B2 | 1990 | 4.95 | 0.75±0.06 |

| HMF-1-1991B2 | 1991 | 5.67 | 0.67±0.04 |

| HMF-1-1992B2 | 1992 | 1.90 | 0.67±0.07 |

| HMF-1-1993B1 | 1993 | 4.02 | 0.68±0.05 |

| HMF-1-1994B1 | 1994 | 3.03 | 0.70±0.04 |

| HMF-1-1995B1 | 1995 | 3.97 | 0.73±0.03 |

| HMF-1-1996B1 | 1996 | 4.38 | 0.67±0.04 |

| HMF-1-1997B1 | 1997 | 3.65 | 0.70±0.03 |

| HMF-1-1998B1 | 1998 | 4.21 | 0.70±0.03 |

| HMF-1-2000B1 | 1999–2000 | 2.55 | 0.69±0.05 |

| HMF-1-2001B1 | 2001 | 3.33 | 0.67±0.07 |

| HMF-1-2002B1 | 2002 | 3.07 | 0.64±0.06 |

| HMF-1-2003B1 | 2003 | 3.38 | 0.72±0.08 |

| HMF-1-2004B1 | 2004 | 4.39 | 0.63±0.05 |

| HMF-1-2005B1 | 2005 | 4.49 | 0.73±0.04 |

| HMF-1-2006B1 | 2006 | 2.67 | 0.74±0.12 |

1σ-errors are given.

One problem associated with 236U as a global oceanic tracer is that during the time of peak fall-out this isotope could not be measured. Therefore localized fall-out is not as constrained as, for example, for 137Cs. However, a future combined approach of using time resolved 236U coral core data, 236U data from ocean water sampling, and global fall-out data (corrected for fission device contribution) on elements which behave similar to uranium in fall-out (e.g. plutonium, cesium) should overcome this obstacle. As a bonus coral core data of 236U may also add value to existing data on 137Cs and 90Sr in ocean water.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Scripps Institution of Oceanography Geological Collections for use of the archived coral core, and B. Katz and two anonymous donors who funded the original expedition to retrieve it from the Turneffe Atoll. This work was partially funded by the FWF Austrian Science Fund (Project No. P21403-N19, Principal Investigator Gabriele Wallner).

Editor: G. Henderson

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at 10.1016/j.epsl.2012.10.004.

Appendix A. Formulae and model description

Separate northern (fN′(t)) and southern (fs′(t)) hemispheric stratospheric fall-out functions are calculated with the box model as shown in the UNSCEAR 2000 report. These function give the kt yield per hemisphere and unit time at any given time t. Only the stratospheric input of fission yield from thermonuclear devices was used. The resulting fall-out functions with monthly resolution are shown in Fig. 3, however with inclusion of the yield to 236U production conversion factor which is determined as the result of the model.

The total stratospheric fall-out with the above restrictions is 114.20 Mt for the northern and 26.84 Mt for the southern hemisphere, a ratio of 4.25:1 between the hemispheres.

Within the hemispheres there is considerable variation of the fall-out intensity depending on rainfall and latitude. We use available 137Cs data and models of 137Cs fall-out (Aoyama et al., 2006) to account for this. We use a south Atlantic end-member of fall-out intensity fSA defined as follows:

| (1) |

where c1 is the conversion to fallout per unit area and the factor of 0.95 the fall-out intensity over the South Atlantic between latitudes of 10°S to 40°S compared to the average fall-out intensity for the southern hemisphere from the UNSCEAR Model.

Similarly we define an end-member for the Caribbean fall-out as:

| (2) |

where a1 is the relative fall-out intensity of the of the Caribbean compared to the northern hemispheric fall-out intensity. This value was adjusted for best fit to 0.57. Estimating a value from the coarse fall-out grid for 137Cs from (Aoyama et al., 2006) seems problematic. At the grid point closest to the location of the HMF-1 core the value would actually be 1.12. However the high fall-out total for 15°N 85°W seems to be quite an outlier to adjacent grid points. Averaging over nine grid points gives (15°N 85°W and the 8 surrounding ones) would put this factor to 0.49. The fitted value lies between these limits.

The assumed input into the mixed layer at time t for water masses travelling from a region in the South Atlantic arriving at the location of the coral core at time t1 is

| (3) |

with t0=t1−T, the moment when northern hemispheric fall-out begins to gain influence. (In reality this has also a seasonal component due to the annual cycle of the ITCZ.) Linear interpolation over time is used between the South Atlantic and the Caribbean end-member. The time T was the second parameter that was adjusted for fitting to the data. Independent of the other fitting parameters a T of 10±1 years seems to be required to explain the measured peak shape within the framework this model.

Vertical diffusion was taken into account implementing Fick's law in an 11 layered model with an ocean of 5000 m of depth. The layer thickness was increased with depth as the bigger gradients in 236U concentration will be in the top layers. The impact of salinity or temperature gradients was not considered. The change in top layer 236U concentration can finally be written as:

| (4) |

with

| (5) |

where Dv is the diffusion constant, C0 and C1 the concentrations in the top and the next deeper layer, h0 and h1 are the thickness of the respective layers (both 100 m, further layers 100 m, 200 m, 300 m, 400 m, 500 m, 600 m, 700 m, 900 m, 1200 m), and hMLD is the mixed layer depth for which we used 100 m. A Dv of 0.1 cm2/s seems to fit the data well until 1995. Lower values have difficulty matching the period from 1975 to 1995.

The uranium that will be built into the coral core at a given time t1 in our model has been advected from the south Atlantic with a 236U concentration of

| (6) |

where tn is beginning of nuclear testing.

What was ultimately measured, is the isotope ratio of 236U to 238U. In order to convert assumptions about the average 238U concentration in surface waters have to be made. We used a uniform value of 3.4 ng/l in line with the U-salintiy relationship of Pates and Muir (2007) and a salinity of 35 psu.

To emulate a coral slice 236U in seawater has to be averaged. The coral slice model used has already been described in Section 3.1.

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

Supplementary Material

References

- Aoyama M., Fukasawa M., Hirose K., Hamajima Y., Kawano T., Povinec P.P., Sanchez-Cabeza J.A. Cross equator transport of 137Cs from North Pacific Ocean to South Pacific Ocean (BEAGLE2003 cruises) Prog. Oceanogr. 2011;89:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama M., Hirose K., Igarashi Y. Re-construction and updating our understanding on the global weapons tests 137Cs fallout. J. Environ. Monit. 2006;8:431–438. doi: 10.1039/b512601k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D.J., Lough J.M. On the nature and causes of density banding in massive coral skeletons. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 1993;167:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Benninger L.K., Dodge R.E. Fallout plutonium and natural radionuclides in annual bands of the Coral Montastrea-Annularis, St-Croix, United-States Virgin-Islands. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1986;50:2785–2797. [Google Scholar]

- Berkovits D., Feldstein H., Ghelberg S., Hershkowitz A., Navon E., Paul M. 236U in uranium minerals and standards. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B. 2000;172:372–376. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch S. Some factors controlling the concentration of uranium in the world ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1980;44:373–377. [Google Scholar]

- Boulyga S.F., Matusevich J.L., Mironov V.P., Kudrjashov V.P., Halicz L., Segal I., McLean J.A., Montaser A., Becker J.S. Determination of 236U/238U isotope ratio in contaminated environmental samples using different ICP-MS instruments. J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom. 2002;17:958–964. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T.A., Marchetti A.A., Martinelli R.E., Cox C.C., Knezovich J.P., Hamilton T.F. Actinide measurements by accelerator mass spectrometry at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B. 2004;223–224:788–795. [Google Scholar]

- Carilli J.E., Norris R.D., Black B., Walsh S.M., McField M. Century-scale records of coral growth rates indicate that local stressors reduce coral thermal tolerance threshold. Global Change Biol. 2010;16:1247–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Carilli J.E., Norris R.D., Black B.A., Walsh S.M., McField M. Local stressors reduce coral resilience to bleaching. PLoS ONE. 2009:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carilli J.E., Prouty N.G., Hughen K.A., Norris R.D. Century-scale records of land-based activities recorded in Mesoamerican coral cores. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009;58:1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.H., Lawrence Edwards R., Wasserburg G.J. 238U, 234U and 232Th in seawater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1986;80:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Christl M., Lachner J., Vockenhuber C., Lechtenfeld O., Stimac I., van der Loeff M.R., Synal H.-A. A depth profile of uranium-236 in the Atlantic Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2012;77:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- de Boyer Montégut C., Madec G., Fischer A.S., Lazar A., Iudicone D. Mixed layer depth over the global ocean: An examination of profile data and a profile-based climatology. J. Geophys. Res. C. 2004;109:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dunk R.M., Mills R.A., Jenkins W.J. A reevaluation of the oceanic uranium budget for the Holocene. Chem. Geol. 2002;190:45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Eigl, R., Srncik, M., Steier, P., Wallner, G., 236U/238U isotopic ratios in small (2 L) sea and river water samples, in preparation. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Eigl, R., Wallner, G., Srncik, M., Steier, P., Winkler, S., 2011. The Suitability of 236U as an Ocean Tracer Mineralogical Magazine, vol. 75, p. 802.

- Fifield L.K. Accelerator mass spectrometry of the actinides. Quat. Geochronol. 2008;3:276–290. [Google Scholar]

- Fritts H. Tree Rings and Climate. Academic Press; London, New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- GEOTRACES, 2011. Available from: 〈http://www.geotraces.org〉.

- Guilyardi E., Madec G., Terray L. The role of lateral ocean physics in the upper ocean thermal balance of a coupled ocean-atmosphere GCM. Clim. Dynam. 2001;17:589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkis M., Fink D., Tuniz C., Vogt S. Accelerator mass spectrometry analyses of environmental radionuclides: Sensitivity, precision and standardisation. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 2000;53:31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(00)00186-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkis M.A.C., Child D., Fink D., Jacobsen G.E., Lee P.J., Mino N., Smith A.M., Tuniz C. Measurement of 236U in environmental media. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res Sect. B. 2000;172:659–665. [Google Scholar]

- Ketterer M.E., Hafer K.M., Link C.L., Royden C.S., Hartsock W.J. Anthropogenic 236U at Rocky Flats, Ashtabula river harbor, and Mersey estuary: three case studies by sector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J. Environ. Radioact. 2003;67:191–206. doi: 10.1016/S0265-931X(02)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S.J., Hurlburt H.E., O'Brien J.J. The connectivity of eddy variability in the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. C. 1999;104:1431–1453. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA, 2012. Ocean surface current analyses real time. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- Pates J.M., Muir G.K.P. U-salinity relationships in the Mediterranean: implications for 234Th:238U particle flux studies. Mar. Chem. 2007;106:530–545. [Google Scholar]

- Paul M., Berkovits D., Ahmad I., Borasi F., Caggiano J., Davids C.N., Greene J.P., Harss B., Heinz A., Henderson D.J., Henning W., Jiang C.L., Pardo R.C., Rehm K.E., Rejoub R., Seweryniak D., Sonzogni A., Uusitalo J., Vondrasek R. AMS of heavy elements with an ECR ion source and the ATLAS linear accelerator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B. 2000;172:688–692. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy C.B., Druffel E.R.M., Hugh D.L. Anomalous levels of 90Sr and 239, 240Pu in Florida corals: evidence of coastal processes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1989;53:1401–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Purser K.H., Kilius L.R., Litherland A.E., Zhao X. Detection of 236U: a possible 100-million year neutron flux integrator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B. 1996;113:445–452. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi A., Kadokuraa A., Steier P., Takahashia Y., Shizumac K., Hoshid T., Nakakukia T., Yamamoto M. Uranium-236 distribution in the Japan/East Sea system seawater, suspended solid and sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi A., Kawai K., Steier P., Quinto F., Mino K., Tomita J., Hoshi M., Whitehead N., Yamamoto M. First results on 236U levels in global fallout. Sci. Total Environ. 2009;407:4238–4242. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Cabeza J.A., Levy I., Gastaud J., Eriksson M., Osvath I., Aoyama M., Povinec P.P., Komura K. Transport of North Pacific 137Cs labeled waters to the south-eastern Atlantic Ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 2011;89:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Steier P., Bichler M., Keith Fifield L., Golser R., Kutschera W., Priller A., Quinto F., Richter S., Srncik M., Terrasi P., Wacker L., Wallner A., Wallner G., Wilcken K.M., Maria Wild E. Natural and anthropogenic 236U in environmental samples. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B. 2008;266:2246–2250. [Google Scholar]

- Steier P., Dellinger F., Forstner O., Golser R., Knie K., Kutschera W., Priller A., Quinto F., Srncik M., Terrasi F., Vockenhuber C., Wallner A., Wallner G., Wild E.M. Analysis and application of heavy isotopes in the environment. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B. 2010;268:1045–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Stramma L., England M. On the water masses and mean circulation of the South Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. C. 1999;104:20863–20883. [Google Scholar]

- Stramma L., Schott F. The mean flow field of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II. 1999;46:279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Toggweiler J.R., Trumbore S. Bomb-test 90Sr in Pacific and Indian Ocean surface water as recorded by banded corals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1985;74:306–314. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumune D., Aoyama M., Hirose K., Bryan F.O., Lindsay K., Danabasoglu G. Transport of 137Cs to the Southern Hemisphere in an ocean general circulation model. Prog. Oceanogr. 2011;89:38–48. [Google Scholar]

- UNSCEAR, 2000. ANNEX C: exposures from man-made sources of radiation. Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. United Nations, New York.

- Vockenhuber C., Christl M., Hofmann C., Lachner J., Müller A.M., Synal H.A. Accelerator mass spectrometry of 236U at low energies. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect B. 2011;269:3199–3203. [Google Scholar]

- Waugh D.W., Hall T.M. Propagation of tracer signals in boundary currents. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2005;35:1538–1552. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.L., Kilius L.R., Litherland A.E., Beasley T. AMS measurement of environmental U-236 Preliminary results and perspectives. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect B. 1997;126:297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.L., Nadeau M.J., Kilius L.R., Litherland A.E. The first detection of naturally-occurring 236U with accelerator mass spectrometry. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B. 1994;92:249–253. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material