Abstract

The beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on plants are expected to be compromised by the negative effects posed by other global changes. However, little is known about ozone (O3)-induced modulation of elevated CO2 response in plants with differential sensitivity to O3. An old (Triticum aestivum cv. Beijing 6, O3 tolerant) and a modern (T. aestivum cv. Zhongmai 9, O3 sensitive) winter wheat cultivar were exposed to elevated CO2 (714 ppm) and/or O3 (72 ppb, for 7h d–1) in open-topped chambers for 21 d. Plant responses to treatments were assessed by visible leaf symptoms, simultaneous measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence, in vivo biochemical properties, and growth. It was found that elevated CO2 resulted in higher growth stimulation in the modern cultivar attributed to a higher energy capture and electron transport rate compared with the old cultivar. Exposure to O3 caused a greater growth reduction in the modern cultivar due to higher O3 uptake and a greater loss of photosystem II efficiency (mature leaf) and mesophyll cell activity (young leaf) than in the old cultivar. Elevated CO2 completely protected both cultivars against the deleterious effects of O3 under elevated CO2 and O3. The modern cultivar showed a greater relative loss of elevated CO2-induced growth stimulation due to higher O3 uptake and greater O3-induced photoinhibition than the old cultivar at elevated CO2 and O3. Our findings suggest that the elevated CO2-induced growth stimulation in the modern cultivar attributed to higher energy capture and electron transport rate can be compromised by its higher O3 uptake and greater O3-induced photoinhibition under elevated CO2 and O3 exposure.

Keywords: elevated CO2, in vivo biochemical parameters, ozone, photosynthesis, relative growth rate, stomatal conductance, Tritium aestivum L., winter wheat.

Introduction

The atmospheric concentration of CO2 is predicted to increase accompanied by a concurrent rise in background ozone (O3) level in the 21st century (Prather et al., 2001; IPCC, 2007). The projected rise in atmospheric CO2 level is expected to increase the growth and yield of many agricultural crops (Long, 1991; Kimball et al., 1995; Long et al., 2006). The positive effects of increased atmospheric CO2 concentration on crop growth and yield may be compromised by the deleterious aspects of atmospheric O3 on crop systems (Long, 1991; McKee et al., 1995; McKee et al., 2000; Long et al., 2006; Ainsworth et al., 2008a ). However, little is known about the extent of O3-induced modification of the beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on crop plants that would have differential responses to atmospheric O3.

Elevated CO2 can cause an increase in biomass and yield of 30–40% in many crops including wheat (10–20%) (Kimball, 1983; Poorter, 1993; McKee and Woodward, 1994; Tuba et al., 1994). The extent of the beneficial effect of elevated CO2 depends largely on the sink strength of a plant (Stitt, 1991; Bowes, 1993; Sicher et al., 2010). Wheat breeding in China, as elsewhere, has progressed over time with reduced plant height (less biomass production) and an increase in grain yield through higher flag leaf photosynthesis (current photosynthesis) and a higher harvest index (Manderscheid and Weigel, 1997; Jiang et al., 2003; Biswas et al., 2008a ). Consequently, the sink strength as well as the extent of the CO2 response in wheat cultivars is decreasing following years of cultivar release (Manderscheid and Weigel, 1997). This may incur a penalty on the potential beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on agricultural production and food security using future high-yielding modern crop cultivars, as the plant CO2 response will be modified further by other global changes including atmospheric O3 (Ainsworth et al., 2008b ). It is therefore important to ensure that selection for improved responsiveness to elevated CO2 is not at the expense of tolerance to other features of global climatic and atmospheric change, notably increased temperature, O3, and drought to maximize the benefit of elevated CO2 on the major food crops (Ainsworth et al., 2008b ).

The extent of downregulation of photosynthesis under elevated CO2 depends on the duration of CO2 exposure, the plant species, the plant developmental stage, the canopy leaf position, and leaf age (McKee et al., 1995; Osborne et al., 1998). The possible physiological mechanisms of downregulation of photosynthesis to elevated CO2 include a decrease in the amounts and activity of Rubisco, and in the capacity for regeneration of the substrate ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) (Stitt, 1991; Bowes, 1993; Sage, 1994). In addition, the intrinsic limitation of photosynthesis under elevated CO2 shifts from CO2 fixation in carboxylation towards energy capture by the photochemical component of photosynthesis (Long and Drake, 1992). Therefore, it should be beneficial for plants to invest relatively more resources into energy capture and electron transport rate at the expense of reduced carboxylation capacity (Long and Drake, 1992; Medlyn, 1996). Whilst growth and yield responses of wheat to elevated CO2 and their underlying mechanisms have been well studied (McKee et al., 1995; Manderscheid and Weigel, 1997), little is known about the mechanistic physiological responses of wheat cultivars with different years of release (i.e., differential sink sizes) to elevated CO2.

In contrast, both old and modern wheat cultivars have been well characterized for their differential responses to O3 (Barnes et al., 1990; Biswas et al., 2008a , b , 2009; Biswas and Jiang, 2011). O3-induced loss of photosynthesis and growth is higher in the recently released winter wheat cultivars due to higher stomatal conductance, a larger reduction in antioxidative activities, and lower levels of dark respiration leading to higher oxidative damage to proteins and integrity of the cellular membrane than in the older cultivars (Biswas et al., 2008a ). It has been reported that the decline in photosynthetic capacity induced by O3 is caused primarily by a decrease in the maximum in vivo rate of Rubisco carboxylation due to a reduction in the activity and/or quantity of Rubisco (Pell et al., 1992; Farage and Long, 1995, 1999; Long and Naidu, 2002; Biswas and Jiang, 2011). In contrast, the impacts of O3 on light-harvesting processes and photosynthetic electron transport are believed to be of secondary importance (Nie et al., 1993; Farage and Long, 1999).

In the combined presence of elevated CO2 and O3 concentrations, the deleterious effect of O3 is often offset by the beneficial effect of elevated CO2 on many crop plants including wheat, although results are variable depending on the crop cultivars, developmental stage, and other growth conditions (Polle and Pell, 1999; McKee et al., 2000; Cardoso-Vilhena et al., 2004). Previous studies have demonstrated that modern wheat cultivars are less responsive to elevated CO2 (Manderscheid and Weigel, 1997) but more sensitive to O3 compared with old cultivars (Barnes et al., 1990; Biswas et al., 2008a , 2009) in terms of growth and yield. It was therefore hypothesized that the beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on an old wheat cultivar could be attributed to its higher O3 tolerance under elevated CO2 and O3 conditions. As protection against O3 (i.e. the efficiency of metabolism of O3-induced reactive oxygen species) is an energy-dependent process (Tausz et al., 2007), it was also hypothesized that O3-induced loss of the beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on plants might be higher in a modern wheat cultivar than in an old cultivar under elevated CO2 and O3. An old and a modern cultivar of winter wheat were therefore utilized to test these hypotheses. Plant responses to elevated CO2 and/or O3 were determined by simultaneous measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence, in vivo biochemical parameters, and growth analysis. The results from this study may be valuable in understanding the extent of the beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on crop cultivars and food security under changing climate conditions such as elevated CO2 and O3.

Materials and methods

Plant establishment and gas treatments

An old (Triticum aestivum cv. Beijing 6; released in 1961) and a modern (T. aestivum L. cv. Zhongmai 9; released in 1997) winter wheat cultivar were selected to assess photosynthetic acclimation and growth under elevated CO2 and/or O3. The study was carried out at the experimental station at the Institute of Botany of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In a temperature-controlled double-glazed greenhouse, three germinated seeds were each sown in 60 plastic pots (6cm diameter, 9cm high) per cultivar for each of the two runs, which were carried out continuously by adjusting planting dates. The pots were filled with local field top soil (clay loam) ideal for wheat growth. Organic C, total N, total P, and total K in the soil were determined as 1.24, 0.045, 0.296, and 14.7g kg–1, respectively. The seedlings were thinned to one per pot d 7 after planting. On d 8 after planting, 15 pots per cultivar were moved to each of four open-topped chambers (OTCs) placed in the same greenhouse. The plants were allowed to grow up to d 17 after planting to adapt to the chamber environments before starting O3 and CO2 treatments. During this adaptation period, all plants received charcoal-filtered air (<5 ppb O3) and ambient CO2. The chambers were illuminated by natural daylight supplemented with fluorescence light providing a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of ~220 µmol m–2 s–1 at canopy height during the 14h photoperiod. An artificial light source was continuously used to extend the day length and to maximize light intensity in the OTCs. The average midday light level (PPFD) in the chambers was ~1230 µmol m–2 s–1. The temperature in the OTCs fluctuated from 17 °C (night) to 27 °C (day), and relative humidity varied from 57 to 85% during the experiment runs. Plants were irrigated as required to avoid drought, and the hard soil crust formed after irrigation was broken to ensure better aeration in the soil.

Pure CO2 was dispensed for 24h a day through manual mass flow meters into blowers and then into the chambers to produce the elevated CO2 treatment. The concentration of CO2 in the OTCs was monitored during the day and night using an infrared gas analyser (GFS-3000; Walz, Germany). O3 was generated by electrically discharging ambient oxygen (Balaguer et al., 1995) with an O3 generator (CF-KG1; Beijing Sumsun Hi-Tech. Co., China) and then was bubbled through distilled water before entering the higher O3 chambers. Water traps were used to remove harmful compounds other than O3 (Balaguer et al., 1995). The flow of O3-enriched air into the OTCs was regulated by manual mass flow controllers. O3 concentrations in the OTCs were continuously monitored at ~10cm above the plant canopy using an O3 analyser (APOA-360; Horiba, Japan), which was cross-calibrated once before starting O3 treatment with another O3 monitor (ML 9810B; Eco-Tech, Canada). The concentrations of CO2 and O3 in the four OTCs was averaged over the entire experimental period: control [CO2, 385±4 ppm+carbon-filtered air (CFA), 4±0.02 ppb O3]; O3 (ambient CO2, 385±4 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb O3 for 7h d–1, 9.00–16.00h); elevated CO2 (CO2, 714±16 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); and elevated CO2+O3 (elevated CO2, 714±16 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb for 7h d–1). To minimize the effects from the chambers and environmental heterogeneities, plants and O3 treatments were switched among the chambers every other day and the location of the plants within the chambers was randomized each time.

Visible symptoms of O3 damage

Visible symptoms were assessed on all leaves of the main stem of each plant after termination of gas treatments. The percentage of mottled or necrotic areas on the leaves was assessed for five plants per cultivar sampled from each of the four gas treatments.

Photosystem II (PSII) functionality

On d 19 of fumigation treatment, five plants per cultivar were sampled from each of the four treatments and taken into an adjacent laboratory for dark adaptation (40min) to ensure maximal oxidization of the primary quinone acceptor. Modulated chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were made in the middle of two fully expanded leaves (i.e. mature: leaf 3, and recently developed: leaf 4) using a PAM-2000 (Heinz Walz, Germany). The room temperature was maintained at 25 °C during measurements. The minimum fluorescence, F 0, was determined with modulated light, which was sufficiently low (<1 µmol m–2 s–1) so as not to induce any significant variable fluorescence. The maximum fluorescence, F m, was determined using a 0.8 s saturating pulse at 8000 µmol m–2 s–1. Data obtained after recording fluorescence key parameters included F 0, F m, variable fluorescence, F v (=F m–F 0), and maximum photochemical efficiency in the dark-adapted state, F v/F m (Krause and Weis, 1991).

Simultaneous measurement of gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence

Two fully expanded leaves (i.e. mature: leaf 3, and recently developed: leaf 4) of each of the sampled plants (four plants per cultivar per treatment) were used for simultaneous measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence with a portable Gas Exchange Fluorescence System (GFS-3000; Heinz Walz). The system was connected to a PC with data acquisition software (GFS-Win; Heinz Walz) and calibrated to the zero point prior to measurements. The measurement was programmed for simultaneously measurement of gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence (Biswas and Jiang, 2011). Relative humidity was maintained at 65% and leaf temperature was set at 25 °C in the leaf chamber. The flow rate was set at 400 µmol s–1 and a CO2 concentration of 400 ppm was maintained in the leaf chamber. The leaf was illuminated with a PPFD of 1500 µmol m–2 s–1 of internal light source in the leaf chamber. Steady-state fluorescence and maximum and minimum fluorescence were recorded along with gas-exchange parameters. In addition, dark-adapted (at least 40min) steady-state fluorescence and maximum and minimum fluorescence were also recorded in leaf 3 and leaf 4 of the sampled plants with the same environmental settings in the leaf chamber except for the light used for gas exchange and light-adapted fluorescence parameters using the Gas Exchange and Fluorescence System. Data obtained as part of the gas exchange measurements included the area-based light-saturated net photosynthetic rate (A sat), stomatal conductance (g s) and intercellular CO2 concentration (C i). Plant intrinsic water-use efficiency (WUEint) at the instantaneous level was calculated as the ratio of A sat/g s (Guehl et al., 1995). After recording fluorescence key parameters in both dark- and light-adapted states, chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters were calculated as follows:

| Quantum yield of PSII, ФPSII=(Fm’–Fs)/Fm’ | (1) |

| Photochemical quenching coefficient, qP=(Fm’–Fs)/(Fm’–F0’) | (2) |

| Non-photochemical quenching, NPQ=(Fm–Fm’)/Fm’ (Bilger and Bjorkman, 1990) | (3) |

| Electron transport rate, ETR=yield×PAR×0.5×0.85 (Meyer et al., 1997) | (4) |

where F m’, F 0’ and F s are the maximum, minimum, and steady-state fluorescence, respectively in the leaf adapted to 1500 µmol m–2 s–1 PPFD and F m is the maximum fluorescence in the dark-adapted leaf.

Determination of A/Ci and A/Q response curves

A/C i (where A is CO2 assimilation rate) and A/Q (where Q is photon flux) response curves were recorded only in the recently developed leaf (leaf 4) of each plant using an automatic curve program with a portable Gas Exchange Fluorescence System (GFS-3000; Heinz Walz). Three plants per cultivar were selected randomly from each treatment for in vivo biochemical parameters. The system connected to a PC was calibrated to zero point prior to measurements. The leaf chamber environment conditions (temperature, flow rate, and relative humidity) were kept the same as described above. Firstly, A/C i curve was recorded and then the A/Q response curve was started automatically. For A/C i curves, the steady-state rate of net photosynthesis under a saturating irradiance of 1500 µmol m–2 s–1 (A sat) was determined at external CO2 concentrations of 400, 300, 200, 100, 50, 400, 400, 600 and 800 ppm. For the A/Q response curves, the CO2 concentration of 700 ppm in the leaf chamber was maintained to visualize photosynthetic acclimation (if any) to elevated CO2. Gas exchange parameters in response to PPFDs of 1800, 1500, 1000, 500, 300, 150, 80, 50, 20, 0 (µmol m–2 s–1) at the leaf surface level were recorded. Each step of the A/C i and A/Q curves lasted for 4 and 3min, respectively, with data being recorded twice at the end of each step. The data obtained for the A/C i curve of each plant were analysed using a curve-fitting program (Photosynthesis Assistant, version 1.1; Dundee Scientific, UK) to obtain the maximum rate of carboxylation by Rubisco (V cmax) and maximum electron transport rate for RuBP regeneration (J max). The program followed the model proposed by Farquhar et al. (1980). Data obtained as a part of the A/Q response curve included CO2 assimilation rate (A), g s and WUEint.

Determination of growth and resource allocation

Plants were sampled for growth analysis before O3 and elevated CO2 treatments (on d 17 after planting) and after 21 d of O3 and elevated CO2 exposure (on d 38 after planting). Five plants per cultivar were harvested from each of the four treatment chambers and partitioned into shoot and root before being dried to a constant weight at 72 °C. The difference in dry weight between the pre-fumigation and final harvest was used to calculate the relative growth rate of whole plants and plant parts over 21 d. The mean plant relative growth rate (RGR), relative growth rate of shoot (RGRs), relative growth rate of root (RGRr), allometric coefficient (K), specific leaf area and net assimilation rate (NAR) were calculated as described by Hunt (1990).

Statistical analysis

The experiment consisted of two blocks (i.e. two runs) in which the four gas treatments were assigned to the chambers in a randomized complete block design. The results from two runs were checked for homogeneity of variance prior to analysis and were then combined for statistical analysis. Analyses of variance was performed for the eight treatment combinations (i.e. two cultivars, two levels of CO2 and two levels of O3) for leaf 3 and leaf 4 on the measurable variables. The data were also analysed for the overall effect of CO2, O3, and cultivar, and for all interactions. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using a general linear model within the SPSS package (PASW Statistics 18.0, Chicago, USA). A Tukey comparison of means was performed when the F-test showed significance (P ≤0.05).

Results

Visible O3 injury

Fully developed leaves of the main stem of each sampled plant were named from the oldest (leaf 1) to the youngest (leaf 5) to assess visible O3 injury of wheat plants. Scoring of visible symptoms demonstrated that there was no difference in the extent of premature leaf senescence (leaf 1) between the cultivars. There was significant cultivar variation in development of visible injury appearing in leaf 2 and leaf 3 (Table 1). No visible symptoms of O3 injury were found in leaf 4 and leaf 5. Elevated O3 led to higher visible O3 injury both in leaf 2 and 3 in the modern cultivar than in the old one. Leaf 2 demonstrated a greater amount of visible O3 injury than leaf 3, irrespective of cultivars. There was no visible symptom of O3 injury in any leaf of the plants exposed to ambient CO2, elevated CO2, and elevated CO2 and O3.

Table 1.

Development of visible symptoms of O3 damage in different leaves of an old (released in 1961) and a modern (released in 1997) winter wheat cultivar exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3. Fully developed leaves of the main stem of each sampled plant were named from the oldest (leaf 1) to the youngest (leaf 5). Control (CO2, 385±4 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); elevated CO2 (CO2, 714±16 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); O3 (ambient CO2, 385±4 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb O3 for 7h d–1, 9.00–16.00h); and elevated CO2+O3 (elevated CO2, 714±16 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb 7h d–1). Overall, the modern cultivar showed significantly (P <0.01) higher level of visible symptoms of O3 injury than the old cultivar. Results are shown as means±1 standard error (n=10).

| Treatment | Visible symptoms of O3 damage (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf 1 | Leaf 2 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 5 | |

| (a) Beijing 6 (1961) | |||||

| Control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CO2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| O3 | 100±2 | 62±6 | 34±4 | 0 | 0 |

| CO2+O3 | 38±4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (b) Zhongmai 9 (1997) | |||||

| Control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CO2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| O3 | 100±2 | 84±9 | 59±5 | 0 | 0 |

| CO2+O3 | 42±5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Dark-adapted chlorophyll a fluorescence

Overall, elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.01) increased F v/F m both in mature (leaf 3) and young (leaf 4) leaves of wheat cultivars (data not shown). Elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.05) increased F m and F v in the young leaf. Elevated O3 significantly decreased F v/F m in mature (P <0.001) and young (P <0.1) leaves. Exposure to O3 decreased F m and F v in the mature leaf, but increased F o, F m, and F v in the young leaf. The variety×CO2 interaction was non-significant for all dark-adapted fluorescence parameters. The old cultivar exhibited a higher F v/F m value in the mature leaf than the modern cultivar at elevated O3 (variety×O3, P <0.05). Elevated CO2 considerably ameliorated O3-induced alterations in basic fluorescence parameters in the mature leaf of both cultivars under elevated CO2 and O3 (CO2×O3, P <0.05). The modern cultivar displayed higher F o, F m, and F v values, along with a lower value of F v/F m in the mature leaf, than the old cultivar under combined gas treatment (variety×CO2×O3, P <0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Minimum fluorescence (F 0), maximum fluorescence (F m), variable fluorescence (F v), and maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (F v/F m) in leaf 3 and leaf 4 of an old (released in 1961) and a modern (released in 1997) winter wheat cultivar exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3 for 21 d in OTCs. Control (CO2, 385±4 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); elevated CO2 (CO2, 714±16 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); O3 (ambient CO2, 385±4 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb O3 for 7h d–1, 9.00–16.00h) and elevated CO2+O3 (elevated CO2, 714±16 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb for 7h d–1). Overall, elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.05) increased F m and F v in the young leaf. Elevated CO2 considerably (P <0.01) increased F v/F m in both matured and young leaves. Exposure to O3 decreased F m and F v in the matured leaf, but increased F 0, F m, and F v in the young leaf. High O3 decreased F v/F m in the mature (P <0.001) and young (P <0.1) leaves of wheat cultivars. Results are shown as means±1 standard error (n=10). Means with the same letter were not significantly different.

| Treatment | F 0 | F m | F v | F v/F m | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | |

| (a) Beijing 6 (1961) | ||||||||

| Control | 248±12c | 237±19bc | 1356±48c | 1299±88c | 1108±38c | 1062±71c | 0.82±0.00a | 0.82±0.01ab |

| CO2 | 246±13c | 216±21c | 1345±53c | 1236±87c | 1099±42c | 1020±73c | 0.82±0.00a | 0.82±0.01ab |

| O3 | 252±15c | 261±22bc | 1209±55c | 1303±97c | 957±46d | 1041±77c | 0.79±0.00c | 0.80±0.01c |

| CO2+O3 | 242±14c | 277±21bc | 1246±50c | 1605±81b | 1004±44cd | 1328±74b | 0.81±0.00ab | 0.83±0.01a |

| (b) Zhongmai 9 (1997) | ||||||||

| Control | 308±15ab | 291±20ab | 1713±51a | 1635±82b | 1405±41a | 1344±75b | 0.82±0.00a | 0.82±0.01ab |

| CO2 | 273±13bc | 263±21bc | 1509±53b | 1459±87bc | 1236±42b | 1196±77bc | 0.82±0.00a | 0.82±0.01ab |

| O3 | 275±17bc | 271±24bc | 1216±57c | 1384±91bc | 941±47d | 1113±78bc | 0.77±0.00d | 0.80±0.01c |

| CO2+O3 | 323±12a | 347±22a | 1586±53ab | 1956±84a | 1262±42b | 1608±76a | 0.80±0.00bc | 0.82±0.01ab |

Simultaneous measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence at ambient CO2 concentration (400 ppm)

Overall, elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.05) increased A sat and g s but decreased C i in both mature and young leaves of wheat cultivars at the CO2 concentration of 400 ppm in the leaf chamber (data not shown). Elevated CO2 also decreased WUEint in the young leaf but not in the mature leaf. Exposure to O3 significantly decreased A sat (P <0.001) but increased C i (P <0.1) in the mature leaf. Elevated O3 did not alter A sat and C i but lowered g s and increased WUEint in the young leaf. Overall, the old cultivar displayed lower values of A sat and g s in the mature leaf but showed a lower g s and higher WUEint in the young leaf than the modern variety. The variety×CO2 interaction was non-significant for all gas exchange parameters in both leaves. The modern cultivar displayed higher C i and a lower WUEint in the young leaf than the old cultivar at elevated O3 (variety×O3, P <0.01). Elevated CO2 ameliorated the O3-induced reduction in mesophyll cell activity (C i) and photosynthetic capacity (A sat) in both leaves of wheat cultivars under elevated CO2 and O3 (CO2×O3, P <0.01; Table 3). The old cultivar showed a higher WUEint in the mature leaf than the modern variety under elevated CO2 and O3 (variety×CO2×O3, P <0.001).

Table 3.

Light saturated rate of net assimilation (A sat), stomatal conductance (g s), intercellular CO2 concentration (C i) and intrinsic water-use efficiency (WUEint) at instantaneous level in leaf 3 and leaf 4 of an old (released in 1961) and a modern (released in 1997) winter wheat cultivar exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3 for 21 d in OTCs. The leaf chamber CO2 concentration was maintained at 400 ppm during gas exchange measurements: control (CO2, 385±4 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); elevated CO2 (CO2, 714±16 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); O3 (ambient CO2, 385±4 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb O3 for 7h d–1, 9.00–16.00h); and elevated CO2+O3 (elevated CO2, 714±16 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb for 7h d–1). Overall, elevated CO2 significantly increased A sat (P <0.01) and g s (P <0.1) in both matured and young leaves, but decreased WUEint in the young leaf. Exposure to O3 significantly decreased A sat (P <0.001), but increased C i (P <0.1) in the matured leaf. Elevated O3 did not alter A sat but decreased g s (P <0.05) and increased WUEint (P <0.001) in the young leaf. Results are shown as means±1 standard error (n=8). Means with the same letter were not significantly different.

| Treatment | A sat (µmol m–2 s–1) | g s (mol m–2 s–1) | C i (ppm) | WUEint (µmol mol–1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | |

| (a) Beijing 6 (1961) | ||||||||

| Control | 8.68±0.63a | 14.73±0.85ab | 0.20±0.02ab | 0.28±0.01bc | 333±8bc | 393±6a | 43.30±4.41ab | 52.89±3.43bc |

| CO2 | 8.31±0.60a | 14.38±0.76ab | 0.19±0.02ab | 0.28±0.01bc | 331±8bc | 348±5cd | 44.05±4.31ab | 52.89±3.07bc |

| O3 | 3.75±0.48b | 13.50±0.98b | 0.13±0.02b | 0.16±0.01d | 360±5a | 359±7bcd | 31.11±3.54b | 82.71±3.97a |

| CO2+O3 | 8.55±0.52a | 16.50±0.76a | 0.17±0.02ab | 0.29±0.01bc | 321±5c | 360±5bc | 51.24±4.84a | 56.66±3.07b |

| (b) Zhongmai 9 (1997) | ||||||||

| Control | 8.93±0.75a | 15.55±0.76ab | 0.21±0.02ab | 0.32±0.01ab | 332±9bc | 388±5a | 43.30±4.35ab | 49.23±3.31bc |

| CO2 | 10.08±0.73a | 16.70±0.74a | 0.25±0.02a | 0.32±0.01ab | 334±8bc | 342±5d | 40.68±4.40ab | 51.90±3.34bc |

| O3 | 4.87±0.53b | 13.70±0.71b | 0.16±0.02ab | 0.24±0.01c | 352±8ab | 391±5a | 36.20±4.40ab | 59.47±3.36b |

| CO2+O3 | 10.08±0.60a | 15.87±0.77ab | 0.25±0.02a | 0.37±0.01a | 334±9bc | 368±5b | 40.72±4.39ab | 42.64±3.30c |

Overall, elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.01) increased ФPSII, q P, and ETR in the young leaf of wheat. Elevated CO2 also considerably increased q P but decreased NPQ in the mature leaf. Exposure to O3 significantly (P <0.01) increased NPQ in the mature leaf of wheat cultivars. Elevated O3 did not alter any light-adapted fluorescence parameter in the young leaf. The modern cultivar showed higher ФPSII, q P and ETR in the mature leaf than the old cultivar under elevated CO2 (variety×CO2, P <0.05). The modern cultivar also showed considerably greater q P in the young leaf than the old cultivar at elevated CO2 (variety×CO2, P <0.1). The variety×O3 interaction was non-significant for all light-adapted fluorescence parameters. The modern cultivar showed higher decreases in ФPSII and q P in the mature leaf than the old cultivar with combined gas treatment compared with elevated CO2 (variety×CO2×O3, P <0.05; Table 4). The modern cultivar also a displayed higher NPQ in the young leaf than the old cultivar under elevated CO2 and O3 (variety×CO2×O3, P <0.1).

Table 4.

Yield (F v’/F m’), quantum yield (ФPSII), photochemical quenching coefficient (q P), non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), and electron transport rate (ETR) in leaf 3 and leaf 4 of an old (released in 1961) and a modern (released in 1997) winter wheat cultivar exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3 for 21 days in OTCs. Chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters were recorded simultaneously with gas exchange measurement. Leaf chamber environment conditions (i.e. PPFD, temperature, relative humidity, flow rate, and CO2 concentration) were the same as those used for gas exchange measurement: control (CO2, 385±4 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); elevated CO2 (CO2, 714±16 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); O3 (ambient CO2, 385±4 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb O3 for 7h d–1, 9.00–16.00h); and elevated CO2+O3 (elevated CO2, 714±16 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb for 7h d–1). Overall, elevated CO2 significantly increased (P <0.01) ФPSII, qP, and ETR in the young leaf but decreased NPQ in the matured leaf. Elevated O3 did not alter any light-adapted fluorescence parameter in the young leaf but considerably increased NPQ (P <0.01) in the mature leaf. Results are shown as means±1 standard error (n=8). Means with the same letter were not significantly different.

| Treatment | F v’/F m’ | ФPSII | q P | NPQ | ETR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | Leaf 3 | Leaf 4 | |

| (a) Beijing 6 (1961) | ||||||||||

| Control | 0.60±0.04 | 0.50±0.01a | 0.098±0.01a | 0.091±0.00ab | 0.13±0.01b | 0.18±0.01bcd | 2.48±0.02bc | 1.78±0.01b | 46±4ab | 57±3ab |

| CO2 | 0.62±0.04 | 0.48±0.01ab | 0.079±0.01ab | 0.095±0.00ab | 0.13±0.01b | 0.20±0.01abc | 2.12±0.02bc | 2.01±0.01ab | 43±4ab | 60±3ab |

| O3 | 0.54±0.03 | 0.50±0.01a | 0.072±0.01ab | 0.084±0.01b | 0.13±0.01b | 0.17±0.01d | 4.87±0.02a | 1.93±0.01ab | 46±3ab | 53±3b |

| CO2+O3 | 0.57±0.03 | 0.51±0.02a | 0.070±0.01ab | 0.092±0.00ab | 0.12±0.01b | 0.18±0.01bcd | 2.43±0.02bc | 1.84±0.01ab | 42±3b | 58±3ab |

| (b) Zhongmai 9 (1997) | ||||||||||

| Control | 0.51±0.04 | 0.51±0.01a | 0.052±0.01b | 0.086±0.00ab | 0.10±0.01b | 0.17±0.01cd | 2.41±0.02bc | 1.67±0.01b | 37±5b | 54±3ab |

| CO2 | 0.59±0.04 | 0.46±0.01b | 0.103±0.01a | 0.094±0.00ab | 0.18±0.01a | 0.21±0.01ab | 1.93±0.02c | 1.55±0.01b | 57±4a | 59±3ab |

| O3 | 0.56±0.03 | 0.51±0.01a | 0.077±0.01ab | 0.082±0.00b | 0.14±0.01b | 0.16±0.01d | 4.54±0.02ab | 1.56±0.01b | 45±4ab | 51±3b |

| CO2+O3 | 0.49±0.02 | 0.46±0.01b | 0.066±0.01ab | 0.098±0.00a | 0.13±0.01b | 0.21±0.01a | 3.16±0.02abc | 2.73±0.01a | 48±5ab | 62±3a |

In vivo biochemical parameters

Elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.05) increased V cmax, J max, and J max/V cmax in the young leaf of wheat cultivars (Fig. 1). Exposure to O3 did not alter the in vivo biochemical parameters in the young leaf. Overall, the modern cultivar showed considerably (P <0.05) lower values of J max and J max/V cmax than the old cultivar. The old cultivar displayed a higher J max/V cmax value than the modern one at elevated CO2 (variety×CO2, P <0.05). The variety×CO2×O3 interaction was non-significant for all in vivo biochemical parameters.

Fig. 1.

Maximum in vivo rate of Rubisco carboxylation (V cmax) and maximum electron transport rate for RUBP regeneration (J max) and J max/V cmax in the young leaf (leaf 4) of an old (released in 1961) and a modern (released in 1997) wheat cultivar exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3 for 21 d in OTCs. Control (CO2, 385±4 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); elevated CO2 (CO2, 714±16 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); O3 (ambient CO2, 385±4 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb O3 for 7h d–1, 9.00–16.00h) and elevated CO2+O3 (elevated CO2, 714±16 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb for 7h d–1). Overall, elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.05) increased V cmax, J max, and J max/V cmax in the young leaf. Exposure to O3 did not alter in vivo biochemical parameters in the young leaf. Results are shown as means±1 standard error (n=6).

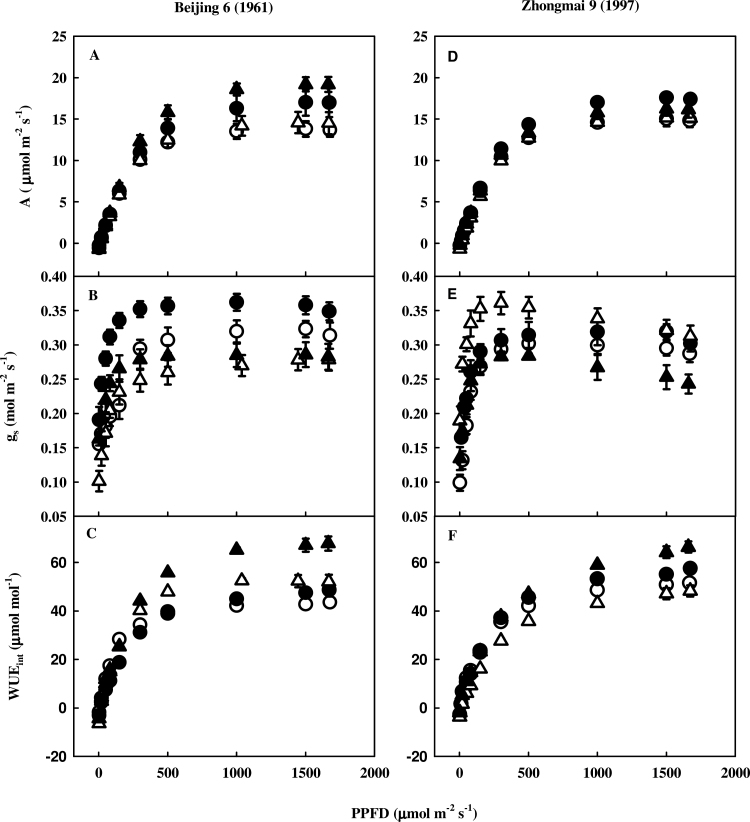

Gas exchange parameters at elevated CO2 (700 ppm) under varying PPFDs

Both cultivars, regardless of treatment, had increased A, g s and WUEint with increasing PPFDs at the CO2 concentration of 700 ppm in the leaf chamber (Fig. 2). None of the wheat cultivars showed photosynthetic acclimation to elevated CO2. Elevated CO2 resulted in higher A in the modern cultivar than in old one at high PPFDs. Exposure to O3 showed a higher relative increase in A in the old cultivar than in the modern one under higher PPFDs. The combined gas treatment decreased A in the modern cultivar but increased A in the old one compared with elevated CO2 at higher PPFDs. Elevated CO2 exhibited a higher relative increase in g s in the old cultivar compared with the modern one over different PPFDs. Exposure to O3 decreased g s in the old cultivar but increased g s in the modern one under varying PPFDs. The combined gas treatment resulted in a decline in g s in both cultivars compared with elevated CO2 over different PPFDs. Elevated CO2 increased WUEint in both cultivars at higher PPFDs. Elevated O3 increased WUEint in the old cultivar but decreased WUEint in the modern one at higher PPFDs. The combined gas treatment resulted in a greater increase in WUEint in the old cultivar than in the modern one relative to elevated CO2 at higher PPFDs.

Fig. 2.

Assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (gs), and intrinsic water-use efficiency (WUEint) at instantaneous level in the young leaf (leaf 4) of an old (released in 1961) and a modern (released in 1997) winter wheat cultivar under varying levels of PPFD after they were exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3 for 21 d in OTCs. Leaf chamber CO2 concentration was maintained at 700 ppm. Control (CO2, 385±4 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3; open circles); elevated CO2 (CO2, 714±16 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3; filled circles); O3 (ambient CO2, 385±4 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb O3 for 7h d–1, 9.00–16.00h; open triangles); and elevated CO2+O3 (elevated CO2, 714±16 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb for 7h d–1; filled triangles). Results are shown as means±1 standard error (n=6).

Plant growth and resource allocation

Overall, elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.001) increased RGR, RGRs, and RGRr, but did not alter K in wheat cultivars (data not shown). Elevated O3 significantly (P <0.05) decreased RGR, RGRs, RGRr, and K in wheat cultivars. Overall, the modern cultivar showed considerably higher (P <0.001) RGR, RGRs, and RGRr values than the old one. The modern cultivar displayed higher RGR, RGRs, and RGRr values than old one at elevated CO2 (variety×CO2, P <0.05). The old cultivar showed considerably higher RGR, RGRs, and RGRr values than the modern one at high O3 (variety×O3, P <0.05). Elevated CO2 significantly ameliorated the negative effects of O3 on RGR, RGRs, and RGRr under elevated CO2 and O3 (CO2×O3, P <0.05). The combined gas treatment resulted in a greater reduction in RGR, RGRr, and K in the modern cultivar than in the old one relative to elevated CO2 (variety×CO2×O3, P <0.05; Table 5).

Table 5.

Relative growth rate of whole plant (RGR), relative growth rate of shoot (RGRs), relative growth rate of root (RGRr), allometric coefficient (K=RGRr/RGRs), specific leaf area (SLA), and net assimilation rate (NAR) of an old (released in 1961) and a modern (released in 1997) winter wheat cultivar exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3 for 21 d in OTCs. Control (CO2, 385±4 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); elevated CO2 (CO2, 714±16 ppm+CFA, 4±0.02 ppb O3); O3 (ambient CO2, 385±4 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb O3 for 7h d–1, 9.00–16.00h); and elevated CO2+O3 (elevated CO2, 714±16 ppm+elevated O3, 72±5 ppb 7h d–1). Overall, elevated CO2 significantly (P <0.001) increased RGR, RGRs, and RGRr but did not alter K. Exposure to O3 significantly (P <0.05) decreased RGR, RGRs, RGRr, and K in wheat cultivars. Results are shown as means±1 standard error (n=10). Means with the same letter were not significantly different.

| Treatment | RGR (g g–1 d–1) | RGRs (g g–1 d–1) | RGRr (g g–1 d–1) | K | SLA (cm2 g–1) | NAR (g m–2 d–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Beijing 6 (1961) | ||||||

| Control | 0.065±0.003c | 0.068±0.003c | 0.056±0.003d | 0.83±0.05a | 603±34ab | 2.34±0.13 |

| CO2 | 0.067±0.002c | 0.070±0.003c | 0.059±0.003d | 0.84±0.05a | 548±32ab | 2.54±0.13 |

| O3 | 0.062±0.002c | 0.066±0.003c | 0.050±0.003e | 0.76±0.04b | 658±30a | 2.17±0.12 |

| CO2+O3 | 0.066±0.002c | 0.069±0.003c | 0.056±0.003d | 0.82±0.04a | 571±30ab | 2.37±0.12 |

| (b) Zhongmai 9 (1997) | ||||||

| Control | 0.075±0.002b | 0.077±0.003b | 0.064±0.003b | 0.84±0.04a | 592±30ab | 2.43±0.12 |

| CO2 | 0.081±0.002a | 0.084±0.003a | 0.071±0.003a | 0.84±0.05a | 527±32ab | 2.76±0.13 |

| O3 | 0.054±0.002d | 0.058±0.003d | 0.040±0.003c | 0.71±0.04c | 655±30a | 1.98±0.12 |

| CO2+O3 | 0.076±0.002b | 0.083±0.003a | 0.065±0.003b | 0.78±0.04b | 492±30b | 2.48±0.12 |

Discussion

Visible symptoms of O3 damage in the two cultivars of winter wheat as affected by elevated CO2

Scoring of visible symptoms in two wheat cultivars exposed to four treatment combinations of O3 and CO2 for 21 d revealed that only elevated O3 showed a differential degree of visible symptoms, varying with leaf age and wheat cultivar. The extent of visible symptoms increased with leaf age, regardless of cultivar. Visible symptoms varied from 62 to 84% and from 34 to 59% in leaf 2 and leaf 3, respectively. This suggested that O3-induced oxidative stress was higher in old and mature leaves, despite their lower O3 uptake compared with recently developed leaves at the upper canopy (Noormets et al., 2010). Significant varietal difference was noted in the visible symptoms of O3 damage that developed on leaf 2 and leaf 3. The modern cultivar showed a higher level of visible symptoms than the old cultivar, irrespective of leaf levels. No visible symptom was found on leaves of the two winter wheat cultivars exposed to elevated CO2, elevated CO2 and O3, and CFA, as found in an O3-sensitive spring wheat cultivar exposed to elevated CO2 and/or O3 (Cardoso-Vilhena et al., 2004).

Photosynthetic and growth responses of an old and modern winter wheat cultivar to elevated CO2

Elevated CO2 is expected to increase the productivity of C3 plants and enhance water-use efficiency at the leaf level through a simultaneous increase in photosynthesis and a decline in stomatal conductance (Cure and Acock, 1986; Eamus, 1991; Drake et al., 1997). We found differential photosynthetic responses of the mature (leaf 3) and recently developed young (leaf 4) leaves of wheat cultivars to elevated CO2. Overall, elevated CO2 significantly increased F v/F m in both mature and young leaves with a larger increase in F v/F m in the former than in the latter. Elevated CO2 also produced a larger increase in A sat in the mature leaf (41%) than in the young leaf (10%). Exposure to elevated CO2 decreased WUEint in the young leaf due to a higher relative increase in g s (26%) at the CO2 concentration of 400 ppm in the leaf chamber. However, elevated CO2 increased both g s and WUEint in the young leaf at the CO2 concentration of 700 ppm in the leaf chamber. This indicated that elevated CO2 increased WUEint in the young leaf without high C i-induced partial stomatal closure. A significant increase in g s in wheat cultivars at elevated CO2, as found in this study, is consistent with previous reports (Norby and O’Neil, 1991; Pettersson and McDonald, 1992; Wang et al., 2000). Elevated CO2 significantly increased ФPSII, ETR, and q P in the young leaf but not in the mature leaf when chlorophyll a fluorescence was recorded simultaneously with gas exchange. The results are consistent with the report of Rascher et al. (2010), which demonstrated an increase in ETR in soybean at elevated CO2. Overall, elevated CO2 significantly decreased NPQ in the mature leaf but did not alter NPQ in the young leaf. We found that a 10% increase in A sat in the young leaf was attributed to an increase in V cmax and J max by 27 and 29%, respectively, under elevated CO2. These results indicated that mature and young leaves show differential strategies in energy acquisition and carbon assimilation. Our findings of higher levels of V cmax and J max in winter wheat under elevated CO2 are consistent with the fact that the short-term response can be attributed largely to stimulation of Rubisco at the vegetative stage of plants when sink strength is less limited (Sharkey, 1988; Long, 1991). However, the stimulation of photosynthesis by elevated CO2 was reflected on growth, as elevated CO2 significantly increased RGR, RGRs, RGRr, and NAR in the wheat cultivars. The results are consistent with the findings of Cardoso-Vilhena et al. (2004), which demonstrate an increased relative growth rate in a spring wheat cultivar under elevated CO2.

The modern cultivar demonstrated higher levels of ETR, q P, and ФPSII in the mature leaf but showed higher q P in the young leaf than the old one at high CO2. This suggested that the modern cultivar had a higher level of energy capture and electron transport rate compared with the old one at elevated CO2. In addition, the modern wheat also displayed higher electron-use efficiency for RuBP regeneration, as documented by a lower value of J max/V cmax compared with the old one at elevated CO2 (variety×CO2, P <0.05). The intrinsic limitation of photosynthesis under elevated CO2 shifts from CO2 fixation in carboxylation towards energy capture by the photochemical components of photosynthesis (Long and Drake, 1992). It is therefore believed that an investment of relatively more resources into the components of light harvesting and electron transport at the expense of reduced carboxylation capacity is beneficial to a plant under elevated CO2 (Long and Drake, 1992; Medlyn, 1996). In agreement with the abovementioned idea, we found that the modern cultivar showed higher relative increases in RGR, RGRs, and RGRr than old one at elevated CO2.

Photosynthetic and growth responses of an old and a modern wheat cultivar to elevated O3

Exposure to O3 significantly reduced the maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (F v/F m) in wheat cultivars, but a higher reduction in F v/F m was noted in the mature leaf (leaf 3) than in the young leaf (leaf 4). The two leaves also showed different mechanisms of photoinhibition. An O3-induced decrease in F m in the mature leaf indicated the occurrence of damage to PSII reaction centres, whilst an O3-induced increase in both F 0 and F m in the young leaf suggested the occurrence of photoinhibition due to an increase in non-radiative thermal deactivation (Butler, 1978). O3-induced damage to PSII in the mature leaf resulted in a significant reduction in A sat accompanied by a greater increase in C i. In contrast, O3-induced non-radiative thermal deactivation of PSII in the young leaf resulted in a non-significant reduction in A sat with a significant decrease in g s. As a result, O3 increased WUEint in the young leaf but not in the mature leaf. Analysis of the quenching components of chlorophyll a fluorescence recorded simultaneously with gas exchange indicated that O3 significantly increased NPQ in the mature leaf but not in the young leaf. These results also suggested that O3-induced loss of A sat in the mature leaf might be due to both stomatal and non-stomatal limitations, as evidenced by the O3-induced reduction in g s and increase in C i (Farage et al., 1991; Farage and Long, 1995; Biswas et al., 2008a ; Biswas and Jiang, 2011). Greater negative effects of O3 on the mature leaf of winter wheat cultivars, as found in this study, are consistent with observations made previously on a cultivar of spring wheat (Cardoso-Vilhena et al., 2004). Loss of Rubisco triggered by exposure to O3 is considered to constitute the primary cause of the O3-induced decline in CO2 assimilation (Farage et al., 1991; Farage and Long, 1995). It has also been documented that the maximal effect of O3 on Rubisco coincided with the period when Rubisco concentration reached its peak (Dann and Pell, 1989; Pell et al., 1992). We found that O3 had no effect on V cmax, J max, and J max/V cmax in the young leaf. This might be the cause underlying the non-significant reduction in A sat in the young leaf of wheat cultivars at elevated O3, as found in the newly expanded leaf of soybean plants exposed to O3 (Bernacchi et al., 2009). Nevertheless, the O3-induced negative effect on photosynthesis resulted in a marked reduction in RGR, RGRs, RGRr, and K in wheat cultivars. Root growth was more negatively affected by O3 than shoot growth, regardless of cultivar, as reported elsewhere (Davison and Barnes, 1998; Biswas et al., 2008a , b ).

The modern cultivar demonstrated a higher loss of PSII efficiency in the mature leaf than the old cultivar at elevated O3 (variety×O3, P <0.01). This suggested that the old cultivar was relatively less sensitive to O3 compared with the modern one, as has been found elsewhere (Barnes et al., 1990, 2008b). In a previous study, the extent of O3 sensitivity of a large number of modern winter wheat cultivars in terms of growth and antioxidative activities was positively associated with O3 uptake and loss of mesophyll cell activity (Biswas et al., 2008a ). We found that the modern cultivar showed a greater loss of mesophyll cell activity, as documented by higher C i in the young leaf than the old wheat cultivar at high O3 (variety×O3, P <0.01). This can be explained by higher O3 uptake, as evidenced by higher g s in both leaves of modern cultivar compared with the old cultivar at high O3 (Biswas et al., 2008a , b ). Consequently, the old cultivar demonstrated higher WUEint in the young leaf than the modern one at high O3. However, higher O3-induced physiological impairment resulted in greater reductions in RGR, RGRs, and RGRr in the modern cultivar compared with the old one. These results are consistent with our earlier reports that demonstrate higher O3 sensitivity of the newly released winter wheat cultivars compared with older ones in terms of growth and grain yield (Biswas et al., 2008a , b ; Biswas and Jiang, 2011).

Differential responses of winter wheat cultivars to the combination of elevated CO2 and O3

The deleterious aspects of atmospheric O3 on crop systems may partly be offset by the beneficial effects of increased atmospheric CO2 concentration on crop plants (Ainsworth et al., 2008a ). In our study, elevated CO2 fully protected both old and modern cultivars against the negative effects of O3 under elevated CO2 and O3. However, the beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on plants varied significantly between the two cultivars under elevated CO2 and O3. We found that the combined gas treatment resulted in higher O3-induced photoinhibition due to non-radiative thermal deactivation of PSII, as evidenced by greater increases in F 0 and F m in the mature leaf of the modern cultivar than that of the old one relative to elevated CO2. High O3-induced photoinhibition in the modern cultivar was associated with higher O3 uptake, as documented by higher g s compared with the old cultivar at elevated CO2 and O3. Consequently, the combined gas treatment showed larger decreases in ФPSII and q P in the mature leaf of the modern cultivar than in that of the old one compared with elevated CO2. In addition, the modern wheat displayed a greater increase in NPQ in the young leaf than the old one under elevated CO2 and O3 relative to elevated CO2. Higher levels of photoinhibition and NPQ in the modern cultivar compared with the old cultivar at elevated CO2 and O3 might be due to a greater reduction in total antioxidant capacity in the modern cultivar at elevated CO2 (Gillespie et al., 2011). Our results also indicated that the old cultivar had a higher WUEint in the young leaf than the modern one under elevated CO2 and O3. Although the modern cultivar displayed a higher energy capture and electron transport rate compared with the old one at elevated CO2, the positive effect of elevated CO2 on plants was largely diminished in the modern cultivar under combined elevated CO2 and O3 exposure. For instance, the modern cultivar showed greater reductions in RGR, RGRs, RGRr, and K than old one in combined elevated CO2 and O3 exposure relative to elevated CO2. These results are in agreement with the notion that the beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on plants may be compromised by nutrient limitation and other environmental stresses (Ainsworth et al., 2008b ). Our results also suggested that the beneficial effects of elevated CO2 on the old cultivar were sustained due to lower O3 uptake and lower O3-induced photoinhibition under elevated CO2 and O3. In addition, a greater O3-induced loss of the positive effects of elevated CO2 on the modern cultivar suggests that elevated CO2-induced growth stimulation in the recently released wheat cultivar attributed to higher energy capture and electron transport rate could be compromised by its higher O3 uptake and greater O3-induced photoinhibition under elevated CO2 and O3 conditions.

In conclusion, elevated CO2 resulted in higher growth stimulation in the modern cultivar attributed to a higher energy capture and electron transport rate compared with the old cultivar. In contrast, O3 induced a greater reduction in growth due to higher O3 uptake and greater loss of PSII efficiency (in the mature leaf) and mesophyll cell activity (in the young leaf) in the modern cultivar than in the old one. Exposure to O3 resulted in greater photoinhibition in the mature leaf compared with the young leaf. The mature and young leaves showed photoinhibition due to the occurrence of damage to PSII reaction centres and an increase in non-radiative thermal deactivation, respectively. Elevated CO2 fully protected both cultivars against the deleterious effects of O3 under elevated CO2 and O3. The modern cultivar showed a greater relative loss of elevated CO2-induced growth stimulation attributed to higher O3 uptake and O3-induced photoinhibition than the old one under combined elevated CO2 and O3 exposure. These results suggest that cultivar selection with improved responsiveness to elevated CO2 as well as tolerance to O3 can maximize agricultural production under the anticipated elevation of CO2 and O3 levels in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Handling Editor, Dr. Elizabeth Ainsworth and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions on an earlier version of the manuscript. D.K.B thanks Protima Biswas for her continuous inspiration and acknowledges funding of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and China Scholarship Council. This is a joint contribution between Institute of Botany of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Agriculture Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). AAFC-ECORC contribution No. 12-358. This study was co-funded by the Shandong Province Taishan Scholarship (no. 00523902), the Innovative Group Grant of Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30521002), the State Science and Technology Supporting Project Eco-agriculture Technological Engineering (2012BAD14B07-8), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30900200).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- A

CO2 assimilation rate

- Asat

area-based light-saturated net photosynthetic rate

- CFA

charcoal-filtered air

- Ci

intercellular CO2 concentration

- ETR

electron transport rate

- F0

minimum fluorescence

- Fm

maximum fluorescence

- Fv

variable fluorescence

- gs

stomatal conductance

- Jmax

maximum electron transport rate for RuBP regeneration

- K

allometric coefficient

- NAR

net assimilation rate

- NPQ

non-photochemical quenching

- O3

ozone

- OTC

open-topped chamber

- PPFD

photosynthetic photon flux density

- PSII

photosystem II

- Q

photon flux

- qP

photochemical quenching coefficient

- RGR

relative growth rate

- RGRr

relative growth rate of root

- RGRs

relative growth rate of shoot

- Vcmax

maximum rate of carboxylation by Rubisco

- WUEint

intrinsic water-use efficiency

- ФPSII

quantum yield of PSII.

References

- Ainsworth EA, Beier C, Calfapietra C, et al. 2008. b Next generation of elevated CO2 experiments with crops: a critical investment for feeding the future world. Plant Cell and Environment 31, 1317–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth EA, Rogers A, Leakey ADB. 2008. a Targets for crop biotechnology in a future high-CO2 and high-O3 world. Plant Physiology 147, 13–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer L, Barnes JD, Panicucci A, Borland AM. 1995. Production and utilization of assimilate in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) leaves exposed to O3 and/or CO2 . New Phytologist 129, 557–568 [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JD, Velissariou D, Devison AW, Holevas CD. 1990. Comparative ozone sensitivity of old and modern Greek cultivars of spring wheat. New Phytologist 116, 707–714 [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Leakey ADB, Heady LE, et al. 2009. Hourly and seasonal variation in photosynthesis and stomatal conductance of soybean grown at future CO2 and ozone concentrations for 3 years under fully open-air field conditions. Plant Cell and Environment 29, 2077–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilger W, Bjorkman O. 1990. Role of the xanthophyll cycle in photoprotection elucidated by measurements of light-induced absorbance changes, fluorescence and photosynthesis in leaves of Hedera canariensis . Photosynthesis Research 25, 173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas DK, Jiang GM. 2011. Differential drought-induced modulation of ozone tolerance in winter wheat species. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 4153–4162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas DK, Xu H, Li YG, Liu MZ, Chen YH, Sun JZ, Jiang GM. 2008. b Assessing the genetic relatedness of higher ozone sensitivity of modern wheat to its wild and cultivated progenitors/relatives. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 951–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas DK, Xu H, Li YG, Sun JZ, Wang XZ, Han XG, Jiang GM. 2008. a Genotypic differences in leaf biochemical, physiological and growth responses to ozone in 20 winter wheat cultivars released over the past 60 years. Global Change Biology 14, 46–59 [Google Scholar]

- Biswas DK, Xu H, Yang JC, et al. 2009. Impacts of methods and sites of plant breeding on ozone sensitivity in winter wheat cultivars. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 134, 168–177 [Google Scholar]

- Bowes G. 1993. Facing the inevitable-plants and increasing CO2 . Annual Review of Plant Physiology 44, 309–332 [Google Scholar]

- Butler WL. 1978. Energy distribution in the photochemical apparatus of photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 29, 345–378 [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso-Vilhena J, Balaguer L, Eamus D, Ollerenshaw JH, Barnes J. 2004. Mechanisms underlying the amelioration of O3-induced damage by elevated atmospheric concentrations of CO2 . Journal of Experimental Botany 55, 771–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cure JD, Acock B. 1986. Crop responses to carbon dioxide doubling. A literature survey. Agriculture and Forest Meteorology 38, 127–145 [Google Scholar]

- Dann MS, Pell EJ. 1989. Decline of activity and quantity of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase and net photosynthesis in ozone-treated potato foliage. Plant Physiology 91, 427–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison AW, Barnes JD. 1998. Effects of ozone on wild plants. New Phytologist 139, 135–151 [Google Scholar]

- Drake BG, Gonzalez-Meler MA, Long SP. 1997. More efficient plants: a consequence of rising atmospheric CO2 . Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 48, 609–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eamus D. 1991. The interaction of rising CO2 levels and temperature with water-use efficiency. Plant, Cell and Environment 14, 25–40 [Google Scholar]

- Farage PK, Long SP, Lechner EG, Baker NR. 1991. The sequence of change within the photosynthetic apparatus of wheat following short-term exposure to ozone. Plant Physiology 95, 529–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farage PK, Long SP. 1995. An in vivo analysis of photosynthesis during short-term ozone exposure in three contrasting species. Photosynthesis Research 43, 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farage PK, Long SP. 1999. The effects of O3 fumigation during leaf development on photosynthesis of wheat and pea: an in vivo analysis. Photosynthesis Research 59, 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Caemmerer von S, Berry JA. 1980. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149, 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie KM, Rogers A, Ainsworth EA. 2011. Growth at elevated ozone or elevated carbon dioxide concentration alters antioxidant capacity and response to acute oxidative stress in soybean (Glycine max). Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 2667–2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guehl JM, Fort C, Ferhi A. 1995. Differential response of leaf conductance, carbon isotope discrimination and water use efficiency to nitrogen deficiency in maritime pine and pedunculate oak plants. New Phytologist 131, 149–157 [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R. 1990. Basic growth analysis. London: Unwin Hyman; [Google Scholar]

- IPCC 2007. Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB, Tignor M, Miller HL, eds. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Annual Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 996 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang GM, Sun JZ, Liu HQ, et al. 2003. Changes in the rate of photosynthesis accompanying the yield increase in wheat cultivars released in the past 50 years. Journal of Plant Research 116, 347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball BA, Pinter PJ, Garcia RL, LaMorte RL, Wall GW, Hunsaker DJ, Wechsung F, Kartschall T. 1995. Productivity and water use of wheat under free-air CO2 enrichment. Global Change Biology 1, 429–442 [Google Scholar]

- Kimball BA. 1983. Carbon dioxide and agricultural yield: an assemblage and analysis of 770 prior observations. Agronomy Journal 75, 779–788 [Google Scholar]

- Krause GH, Weis E. 1991. Chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis: the basics. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 42, 313–349 [Google Scholar]

- Long SP. 1991. Modification of the response of photosynthetic productivity to rising temperature by atmospheric CO2 concentrations: has its importance been underestimated? Plant, Cell and Environment 14, 729–739 [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Ainsworth EA, Leakey ADB, Nosberger J, Ort DR. 2006. Food for thought: lower than expected crop yield stimulation with rising CO2 concentrations. Science 312, 1918–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Drake BG. 1992. Photosynthetic CO2 assimilation and rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations. In: Baker NR, Thomas H, eds. Crop photosynthesis: spatial and temporal determinants Amsterdam: Elsevier; 669–704 [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Naidu SL. 2002. Effects of oxidants at the biochemical, cell and physiological levels. In: Treshow M, ed. Air pollution and plants. London: John Wiley; 68–88 [Google Scholar]

- Manderscheid R, Weigel HJ. 1997. Photosynthetic and growth response of old and modern spring wheat cultivars to atmospheric CO2 enrichment. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 64, 65–73 [Google Scholar]

- McKee IF, Farage PK, Long SP. 1995. The interactive effects of elevated CO2 and O3 concentrations on photosynthesis in spring wheat. Photosynthesis Research 45, 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee IF, Mulholland BJ, Craigon J, Black CR, Long SP. 2000. Elevated concentrations of atmospheric CO2 protect against and compensate for O3 damage to photosynthetic tissues of field-grown wheat. New Phytologist 146, 427–435 [Google Scholar]

- McKee IF, Woodward FI. 1994. The effect of growth at elevated CO2 concentrations on photosynthesis in wheat. Plant, Cell and Environment 17, 853–859 [Google Scholar]

- Medlyn BE. 1996. The optimal allocation of nitrogen within the C3 photosynthetic system at elevated CO2 . Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 23, 593–603 [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U, Kollner B, Willenbrink J, Krause GHM. 1997. Physiological changes on agricultural crops induced by different ambient ozone exposure regimes I. Effects on photosynthesis and assimilate allocation in spring wheat. New Phytologist 136, 645–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie GY, Tomasevic M, Baker NR. 1993. Effects of ozone on the photosynthetic apparatus and leaf proteins during leaf development in wheat. Plant, Cell and Environment 16, 643–651 [Google Scholar]

- Noormets A, Kull O, Sober A, Kubiske ME, Karnosky DF. 2010. Elevated CO2 response of photosynthesis depends on ozone concentration in aspen. Environmental Pollution 158, 992–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norby RJ, O’Neil EG. 1991. Leaf area compensation and nutrient interactions in CO2-enriched seedlings of yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera L.). New Phytologist 117, 515–528 [Google Scholar]

- Osborne CP, LaRoche J, Garcia RL, Kimball BA, Wall GW, Pnter PJ, Lamorte RL, Hendrey GR, Long SP. 1998. Does leaf position within a canopy affect acclimation of photosynthesis to elevated CO2? Plant Physiology 117, 1037–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell EJ, Eckardt N, Enyedi AJ. 1992. Timing of ozone stress and resulting status of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and associated net photosynthesis. New Phytologist 120, 397–405 [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson R, McDonald AJS. 1992. Effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentration on photosynthesis and growth of small birch plants (Betula pendula Roth.) at optimal nutrition. Plant, Cell and Environment 15, 911–919 [Google Scholar]

- Polle A, Pell EJ. 1999. Role of carbon dioxide in modifying the plant response to ozone. In: Luo Y, Mooney HA, eds. Carbon dioxide and environmental stress. San Diego: Academic Press; 193–213 [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H. 1993. Interspecific variation in the growth response of plants to elevated ambient CO2 concentration. Vegetatio 104, 77–97 [Google Scholar]

- Prather M, Ehhalt D, Dentener F, et al. 2001. Atmospheric chemistry and greenhouse gases. In: Houghton JT, Ding Y, Griggs DJ, Noguer M, van der Linden PJ, Dai X, Maskell K, Johnson CA, eds. Climate change 2001: the scientific basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 239–287 [Google Scholar]

- Rascher U, Biskup B, Leakey ADB, McGrath JM, Ainsworth EA. 2010. Altered physiological function, not structure, drives increased radiation-use efficiency of soybean grown at elevated CO2 . Photosynthesis Research 105, 15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. 1994. Acclimation of photosynthesis to increasing atmospheric CO2: the gas exchange perspective. Photosynthesis Research 39, 351–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD. 1988. Estimating the rate of photorespiration in leaves. Physiological Plantarum 73, 147–152 [Google Scholar]

- Sicher Jr RC, Bunce JA, Matthews BF. 2010. Differing responses to carbon dioxide enrichment by a dwarf and a normal-sized soybean cultivar may depend on sink capacity. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 90, 257–264 [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M. 1991. Rising CO2 levels and their potential significance for carbon flow in photosynthetic cells. Plant, Cell and Environment 14, 741–762 [Google Scholar]

- Tausz M, Grulke NE, Wieser G. 2007. Defense and avoidance of ozone under global change. Environmental Pollution 147, 525–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuba Z, Szente K, Koch J. 1994. Response of photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, water use efficiency and production to long-term elevated CO2 in winter wheat. Journal of Plant Physiology 144, 661–668 [Google Scholar]

- Wang XZ, Curtis PS, Prigitzer KS, Zak DR. 2000. Genotypic variation in physiological and growth responses of Populus tremuloides to elevated CO2 concentration. Tree Physiology 20, 1019–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]