Abstract

Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are pure anion uniporters, which mediate fatty acid (FA) uniport leading to FA cycling. Protonated FAs then flip-flop back across the lipid bilayer. An existence of pure proton channel in UCPs is excluded by the equivalent flux-voltage dependencies for uniport of FAs and halide anions, which are best described by the Eyring barrier variant with a single energy well in the middle of two peaks. Experiments with FAs unable to flip and alkylsulfonates also support this view. Phylogenetically, UCPs took advantage of the common FA-uncoupling function of SLC25 family carriers and dropped their solute transport function.

Keywords: mitochondrial uncoupling proteins, fatty acid anion uniport, anion uniport, proton conductance, Eyring barrier model for transport

1. Introduction – mitochondrial uncoupling proteins

The uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are members of the mitochondrial solute carrier gene family SLC25 which contains 46 members in mammals [1–11]. Five distinct isoforms have been identified as members of the UCP subfamily in mammals, including UCP1 to UCP5, and up to six isoforms in plants, originally called PUMPn. The UCP2 isoform exhibits the widest expression pattern in mammals, UCP3 is expressed typically in skeletal muscle, and UCP4 and UCP5 are expressed typically in brain [3,9,10]. The UCP1 isoform was originally ascribed exclusively to brown adipose tissue [3,4,6–8], but it has recently been reported in thymocytes [7], skin [12], brain, [13] and pancreatic β-cells [14].

The transport phenotype of UCPs has been studied extensively for UCP1, UCP2, UCP3, and PUMP1. Classic mitochondrial experiments as well as reconstitution studies have revealed three types of phenomenological results (categories of transport) for these UCPs. (a) Apparent electrophoretic transport of protons. Fatty acid (FA)-facilitated UCP-mediated proton uniport is of course the cause of mitochondrial uncoupling and energy dissipation [4]. (b) Electrophoretic transport of alkylsulfonates. UCP1 [6,15–22], UCP2 and UCP3 [23], and PUMP1 [24,25] catalyze anion uniport of long-chain alkylsulfonates, which are univalent, hydrophobic fatty acid mimetics. (c) Electrophoretic transport of halides and other polar univalent anions has been reported for UCP1, i.e. electrophoretic transport of Cl− and other halides [6,16], along with other small anions such as hypophosphate [15], pyruvate and other keto-carboxylates [15,21], and short-chain alkylsulfonates [15]. Recombinant reconstituted human UCP2 and UCP3 were mentioned to transport chloride [26]. Interestingly, transport of chloride, pyruvate, and other small anions has been excluded for PUMP1 [24,25].

This review is focused on the mechanism of UCP-mediated proton and anion uniport. Two fundamentally different models have been proposed. Klingenberg and coworkers [8] favor the view that UCPs are direct proton uniporters, and fatty acids only facilitate the proton uniport. We favor the view that any UCPn isoform is a pure anion uniporter and that uncoupling is mediated by fatty acid cycling [3–7,27]. In this respect, anion uniport might occur outside the central cavity, at the protein-lipid interface. The FA-cycling model [3–7,27] has been supported by numerous reconstitution studies in liposomes [3–5,7,17–20,22–25] and black lipid membranes (BLM) [28–33]. In this model, FA anions are regarded as true anionic transport substrates of UCPs, so that the anionic FA head group is translocated by UCPs. After protonation on trans-side, a rapid return of the protonated FA through the bilayer occurs yielding the proton movement [18]. In the absence of inhibitory concentrations of nucleotide such mechanism would act until all cycling substrates are removed from the membrane either by metabolism or being bound to sites with higher affinities, if exist [4]. Moreover, transport of poly-unsaturated FAs (PUFAs) is faster with UCP1 and UCP2 reconstituted into liposomes [28] and BLM [32,33]. Also hydroperoxy-FAs [29] and nitrolinoleic acid (Jabůrek et al., unpublished) have been confirmed as UCP2 anion transport substrates [29]. Consequently, both schools of thought agree that FAs are essential for UCPn-mediated proton uniport [8,18]. The differing roles of FAs in the two models has given rise to terminology that may be confusing to those new to the field. Thus, the proton uniport school considers FAs to “activate” the UCPs, whereas the FA cycling school considers FAs to be transport substrates of the UCPs.

We present these two models in details and discuss their relevance toward the available experimental data. We also address the question of how the UCPs are integrated into the mitochondrial solute carrier family. We suggest that during its evolution, UCPs dropped the solute transport function altogether, while preserving the uncoupling function that is exhibited by several of the solute carriers, including the adenine nucleotide translocase.

2. UCP as a hypotetical electrophoretic proton uniporter

Klingenberg [8] and Nicholls [6] hypothesized the existence of a pure proton uniport pathway in the UCPs, in which FAs are enhancers of otherwise basal H+ uniport. A considerable disadvantage of this model is that it does not account at all for the well-established anion uniport function of the UCPs.

2.1. Other proton channels

The membrane (FO) sector of the ATP synthase contains a linear array of ionizable amino acid carboxyl residues [34]. It conducts protons with an ohmic conductance of 10 fS [35]. In the simplest model, deprotonation on the trans-side and protonation on the cis-side evokes jumps of H+ unidirectionally toward the deprotonation side. Proton transport through gramicidin has been described as H+ jumps through a single-file chain of water molecules, using the hydrogen-bond network (a Grotthuss-type mechanism) [36]. There is evidence, however, that more sophisticated models are required for gramicidin [37,38], including conformational modeling of known structures, such as has been applied to the M2 H+ channel [39]. Thus, protein-mediated H+ conductance occurs in nature, but it is important to note that there is a structural requirement for residues to facilitate H+ transport.

2.2. Does the UCP cavity contain amino acid residues favoring H+ transport?

There is no array of easily protonatable residues found within the central cavity region common to all members of the mitochondrial solute carrier family [1,2,11]; however, Echtay, et al. [40] have suggested D28 as being involved in proton transport by UCP1.

2.3. Can fatty acids enhance H+ uniport via UCP?

FAs are essential for UCP-mediated H+ uniport [8,17,30–33]. Several other “enhancers” have been suggested, including 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and similar compounds [41]. Klingenberg [8] considers the role of FA is to provide sites for H+ jumps through the UCP cavity or at least external sites directing H+ to the hypothetical H+ channel in UCPs. Thus, a FA anion head group positioned at the middle of the membrane would hypothetically provide a site for a single-jump model. The free energy of such an awkward distribution of FA would seem to be highly unfavorable. If the free energy were reduced by a cationic residue in the cavity, the carboxylate would be neutralized and would lose its ability to accept protons.

3. UCP as an electrophoretic anion uniporter

It is generally agreed that UCP1 catalyzes nucleotide-inhibited, electrophoretic anion uniport, as summarized in Introduction. Some years ago, we found that UCP1 transports alkylsulfonates and that the rate and alkylsulfonate affinity increase with hydrophobic chain length [15,22]. The alkylsulfonates are analogues of FAs, with the crucial difference that the pKa of the sulfonate head group is ~ 0, thus preventing head group protonation. The transport kinetics of the alkylsulfonates were also found to be strikingly similar to the [FA]-dependence of uncoupling. We reasoned that, if long-chain alkylsulfonates are transported by UCP, there is no obvious reason that FA would not be transported. This led to the FA cycling model of UCP action [18], which was first proposed by Skulachev [27]. Other support has been provided by the inability of so-called inactive FAs to induce H+ uniport by UCP1 [19,20]. These inactive FAs are unable to flip-flop in a protonated form across the membrane, hence this negative result excluded the model of Klingenberg [8].

3.1. Eyring barrier model for ion leak across biomembranes

Unfacilitated ion leak across biomembranes is of great significance for bioenergetics and can be used as a starting point for considering anion uniport via the UCPs. Classic Eyring theory has been applied by Garlid et al. [42,43] to problems of ion leak across the bilyer in liposomes and across the inner membrane of mitochondria (Fig.1). A nearly identical equation was later derived by Fujitani and Bedeaux [44], based on ion velocity distribution and density fluctuation of lipids. Both of these theories can be extended to cases where ion flux is promoted by the existence of one or more ion binding sites on a protein, as discussed below.

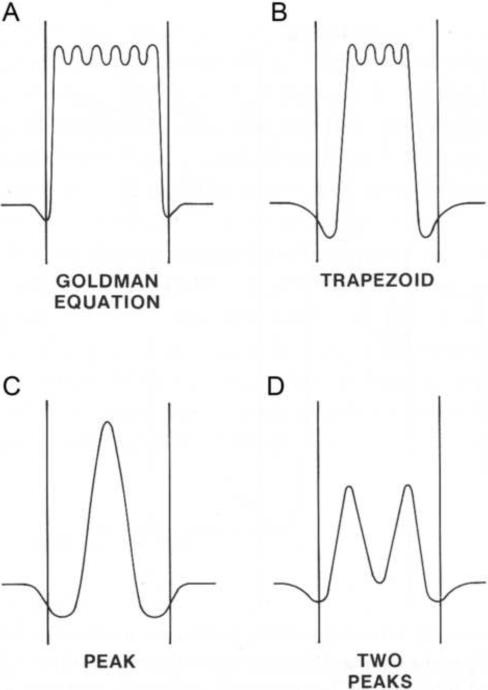

Fig. 1. Classic and Eyring barrier models for typical energy barrier profiles and their limiting cases.

Energy profiles are illustrated corresponding to (A) Goldman equation, (B) trapezoid barrier, (C) single-peak, and (D) double-peak energy barrier with a well (binding site).

The single Eyring barrier model (C) and its modification containing an energy well (D) are described in the Sections 3.1 and 3.2, respectively. A Goldman equation, J = P· u ·(C1·eu - C2 / (eu2 - 1), is a special case of equation {8} with N approaching to infinity (Fig.1A) [42]. Alternatively a trapezoid barrier (Fig.1B) is introduced [42], for which flux J is given, J = P ·W·u·(C1·eu - C2·e−u/22) / (eWu/2 - e−Wu/2), where W is a fractional width of the trapezoid (Fig.1B). At the limit W = 1, one gets the Goldman equation, whereas at the limit W = 0, equation changes to the expression for a single sharp peak (β= 0.5) (Fig.1C).

Let's recall how the Garlid's simplification was derived [42]. Assume the membrane energy barrier has a single sharp maximum (peak), as shown in Fig. 1C. This assumption appears to be valid for biomembranes rich in integral membrane proteins. The probability of an ion having sufficient energy to move to the peak is given by a Boltzmann distribution term e−Δμp/RT, where Δμp = μp − μwell is the Gibbs energy of the ion at the peak relatively to its value of the energy well at the membrane surface. The net flux of the ion J is proportional to the probability to reach the peak from either side and to the ion concentration at the peak, Cp:

| {1} |

while Gibbs energies are expressed as follows:

| {2}, {3} |

where z is the valence of the ion, ϕ is the local electrical potential, and C is the local concentration of the ion at the denoted locations. R, T, and F are gas constant, absolute temperature, and Faraday constant, respectively. The term Δμop/RT represents the height of the barrier. For a sharp barrier located halfway through the membrane profile the local potential difference ϕp−ϕ1 is equal to ΔΨ/2, if the constant field assumption is applied [42]. Equation {1} is therefore reduced to the following equation:

| {4} |

| {5},{6} |

For hydrophilic ions, the reasonable assumption is made that the membrane is symmetric with respect to surface potentials and ion extraction and that surface energy wells are not saturated with ions [42]. Consequently, aqueous ion concentrations may be used, and the surface partition coefficient is then included in the permeability constant.

At the high values of ΔΨ maintained by mitochondria, the back-flux of ions is negligible. Thus, at 180 mV, the back-flux of cations is about 1000-fold smaller than the forward flux. This allows a further simplification of equation {4}:

| {7} |

Equation {7} fits very well with experimental data for non-ohmic flux-voltage relationships for cation and proton leak in lipid vesicles and for cation leak in mitochondrial membranes [42,45]. The flux-voltage curves for proton leak and cation leak (tetraethylammonium) are superimposable when adjusted for their permeability constants [46]. This conveys the important information that leak of (hydrated) protons follows the same pathway as leak of (hydrated) cations, so there is no “special” H+ leak pathway, such as jumps along a water wire.

3.2. Eyring barrier model when there are energy wells in the transport pathway

The flux J for an ion crossing N uniformly high, sharp barriers at the membrane potential ΔΨ (Fig.1D) with all the simplifications outlined above, is described as [42]:

| {8} |

| {9} |

Again, at high ΔΨ, when the back-flux is negligible, equation {8} reduces to:

| {10} |

For this expression Garlid et al. [42] have introduced parameter β equal to 1/2N, leading to:

| {11} |

Note that for a single energy well (binding site) in the middle of the membrane will divide the barrier into two peaks, and the parameter β will equal 0.25 (Fig. 1D).

3.3. A summary of experimental evidence for the FA cycling hypothesis

From our first presentation of the FA cycling mechanism of uncoupling by the UCPs [18], we have emphasized that evidence for the physical transport of FA anion is indirect. This is necessarily so, because anion transport by UCP is orders of magnitude slower than the subsequent protonation and back-diffusion of the protonated species, making it impossible to measure FA anion uniport in isolation. The FA cycling hypothesis is supported by a broad array of data obtained in mitochondria, liposomes, and black lipid membranes [3–5,7,17–20, 22–25, 28–33,47] and has not been refuted by experiment. Importantly, it encompasses in one model the two distinct transport functions of the UCPs - anion uniport and proton uniport. The following summarizes three major areas of experimental support.

3.3.1. Energy barrier studies

We investigated the flux-voltage dependence of halide uniport in liposomes reconstituted with UCP1, with results contained in Fig. 2A and 2B. Cl− and Br− fluxes were exponential with diffusion potential (voltage), as predicted by Equation {11}. The slopes of the semilogarithmic plots in Figure 2B give values for the parameter β that are close to 0.25. As described in Section 3.2, this suggests a single binding site (energy well) mid-way in the transport pathway that is surrounded by two sharp energy barrier peaks (Fig. 1D). We compared this behavior to that of thiocyanate (SCN−) anion, this time in liposomes without UCP (Fig. 3A and 3B). Here, as predicted for unfacilitated diffusion across the barrier, we obtained β = 0.5, consistent with a sharp energy barrier near the center of the membrane.

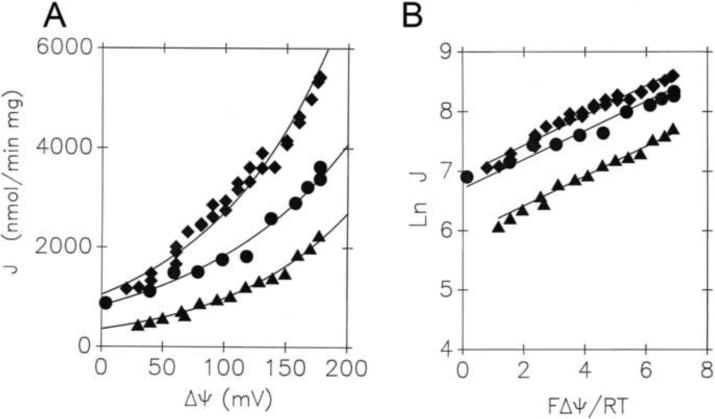

Fig. 2. Nonohmic Cl− and Br− uniport mediated by reconstituted UCP1 reflects a double-peak energy barrier with a well (binding site) in the middle.

Rates of ion uptake in UCP1-proteoliposomes (J) for Cl− (●), Br− (◆), and Br− in vesicles loaded with 2 mM GDP (▲) are plotted as a function of K+ diffusion potential ΔΨ in direct plots, where fits of the data were done using equation {11} (A). Data were linearized while plotting ln J vs. zFΔΨ/RT (B). Fits yielded (R2 of 0.98) the following parameters β: 0.22 ± 0.01 for Cl− flux and 0.25 ± 0.01 for Br− flux into UCP1-proteoliposomes; and 0.26 ± 0.02 for Br− flux into GDP-loaded UCP1-proteoliposomes.

ΔΨ was calculated from the Nernst distribution of K+ in the presence of 1 μM valinomycin. Reconstitution of hamster brown adipose tissue UCP1 and 6-methoxy-N-(3-sulfopropyl)-quinolinium (SPQ) fluorometric quantification of ion fluxes has been performed as described in [17]. UCP1-proteoliposomes contained 50 mM tetraethyl ammonium (TEA)-sulfate, 100 mM TEA- N-tris(hydroxymethyl)-methylamino-ethanesulfonic acid (TES) pH 7.2, containing 0.14 mM KCl (KBr), while the external assay medium was composed of 150 mM KCl (KBr, respectively), 25 mM TEA-TES, pH 7.2, for maximum ΔΨ, which was further decreased by proportional mixing with 150 mM TEA-Cl (TEA-Br, respectively), 25 mM TEA-TES, pH 7.2.

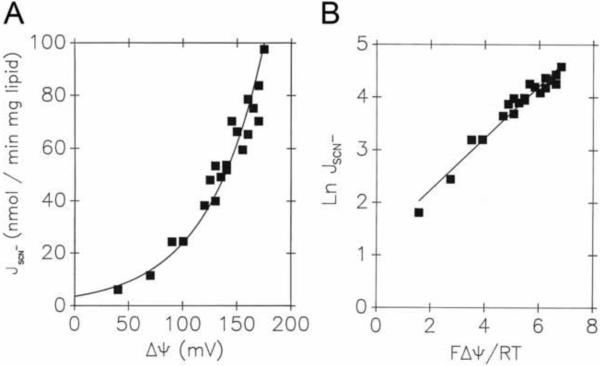

Fig. 3. Nonohmic SCN− uniport in protein-free liposomes reflects a single-peak energy barrier.

Rates of ion uptake in lecithin liposomes (JSCN−) for SCN− are plotted as a function of K+ diffusion potential ΔΨ in direct plots, where data were fitted by equation {11} (A). Data were linearized while plotting ln J vs. zFΔΨ/RT (B). The fit yielded (R2 of 0.98) the parameters β of 0.49 ± 0.02.

ΔΨ was calculated from the Nernst distribution of K+ in the presence of 10 μM valinomycin. Liposomes were prepared and SPQ fluorometric quantification of ion fluxes has been performed as described in [17]. Liposome lumen contained 50 mM TEA-sulfate, 75 mM TEA-TES pH7.2, 25 mM Li-TES, and 0.14 mM KSCN, while the external assay medium was composed of 25 mM KSCN,125 mM KTES, 25 mM Li-TES, pH 7.2, for maximum ΔΨ, which was further decreased by proportional mixing with 25 mM LiSCN, 150 mM TEA-TES, pH 7.2.

Recent data from Rupprecht, et al. [33] are in agreement with these results. They studied the flux-voltage characteristics of H+ flux in BLM reconstituted with UCP1 and UCP2. In the presence of unsaturated fatty acids, they obtained β = 0.3. However, with sole UCP in BLM without the fatty acid only negligible conductance has been found. Its flux-voltage characteristics exhibited β = 0.2. Similar negligible conductance for only BLM free of protein and FAs has been measured. Thus Rupprecht, et al. [33] have considered even the trapezoid barrier (Fig. 1B) to fit these data obtained in the absence of FAs.

Due to the polarization potential of biomembranes, the energy barrier for anions is intrinsically lower than that for cations. The panoply of anions transported by UCP includes very hydrophobic anions, such as the long-chain alkylsulfonates and, of course, FA. Given the preference of UCPs for hydrophobic substrates, it seems likely that all or part of the conductance pathway lies on the outer surface of the protein, at the lipid-protein interface [18]. Thus, the energy well is probably created by a polar residue in UCP located near the center of the membrane. The residue D28, identified by mutagenesis as being essential for UCP1-mediated uncoupling [40] is located near this region and could serve this function. We infer that inhibition by nucleotide binding to its pocket in UCP causes a conformational change that shields the polar residue or moves it away from the lipid interface.

3.3.2. Studies using inactive fatty acids

As noted, fatty acids “activate” the UCPs - that is, they induce protonophoretic H+ transport [3–10]. We set out to identify FAs that did not activate UCP, and we found many. Some were dicarboxylic, with a carboxyl at both ends, others were bipolar in other ways, such as ω-hydroxy and ω-phenyl fatty acids [19,20]. These “inactive” FAs are unable to induce H+ uniport via UCP [20], nor they do induce charge movement [20,47]. They do not compete with Cl− uniport [20]. Furthermore, they do not induce H+ movement by virtue of nonionic diffusion [19]. These features emphasize the fact that the FA cycling mechanism employs membrane flip-flop for both legs of the cycle. The polar groups prevent flip-flop, so uncoupling is prevented. Again, these results are most easily explained if FA “activation” is understood as FA anion transport by UCP [3,5,7,18].

3.3.3. Alkylsulfonate studies

We have long considered UCP-mediated anion uniport to hold the key to the mechanism of uncoupling, because, as pointed out by Nicholls and Locke [48], there is no physiological role for this transport. It is a case of “The dog that didn't bark”. Moreover, there was a brief period of controversy over whether UCP1 even transported anions (referenced in [15]). Accordingly, we set out to clarify the nature and extent of anion uniport by UCP1, and found a large number of new substrates, including alkylsulfonates, alkylsulfates, oxohalogenides, hypophosphate, and pyruvate [15]. Each of these anions were shown to compete with Cl− for transport by the reconstituted uncoupling protein. Although the spectrum is broad, we found strong structural requirements for transport: the anion must be monovalent, and polar groups must be close to the charge, hence must not be attached to alkyl or aryl chains. The most striking finding was that transport increased dramatically with anion hydrophobicity.

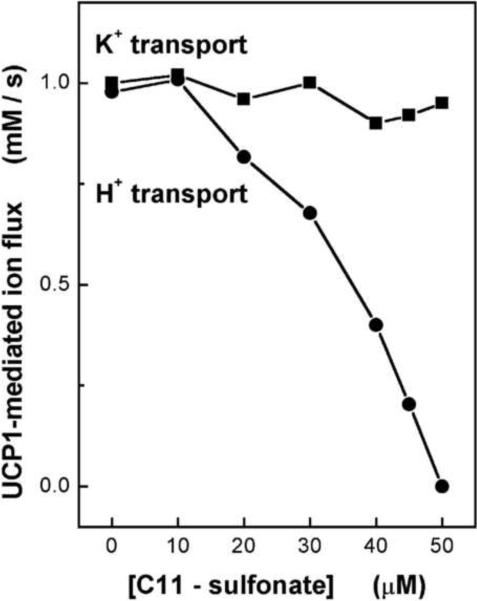

Among this group of anions, we chose to focus on the alkylsulfonates, because they are analogues of fatty acids. In particular, we compared the properties of laurate with its close analogue, undecanesulfonate (C11-sulfonate). We found the Km for laurate as a mediator of H+ uniport to be about the same as the Km for C11-sulfonate uniport, and their Vmax values were also similar [18]. Moreover, C11-sulfonate inhibited laurate-induced H+ uniport with competitive kinetics. Alkylsulfonates exhibit a very useful difference from fatty acid anions, in that the sulfonate head group is an extremely strong anion, and cannot be protonated at biological pH values. Thus, alkylsulfonates cannot diffuse back across the bilayer by nonionic diffusion. We exploited this difference in several ways. Fig. 4 contains data from an experiment in which [laurate] and [C11-sulfonate] were varied, while the total substrate anion concentration was maintained constant [22]. Counter-ion was provided by K+ in the presence of valinomycin. Two measurements were made: H+ efflux and K+ influx, the latter as a measure of UCP-mediated charge movement. It can be seen that charge movement remained constant at all combinations of laurate and C11-sulfonate, whereas H+ efflux dropped to zero as C11-sulfonate took over the transport pathway by competition with laurate. The results of this experiment are predicted by the FA cycling hypothesis, but they are very difficult to explain in terms of the H+-conducting hypothesis of UCP uncoupling.

Fig. 4. Simultaneous lauric acid cycling and C11-sulfonate uniport in UCP1-proteoliposomes.

H+ efflux and K+ influx are plotted vs. C11-sulfonate concentration. Total substrate anion concentration [C11-sulfonate] plus [lauric acid] was held constant at 50 μM as [C11-sulfonate] was increased. H+ efflux and K+ influx were indicated by fluorescent probes SPQ and PBFI loaded in two parallel proteoliposomal preparations, respectively. Ion fluxes were initiated by 0.1 μM valinomycin in the presence of a [K+ ] gradient. Reconstitution of hamster brown adipose tissue UCP1 was performed as described in [22]. UCP1-proteoliposomes contained 30 mM TEA-TES, pH 7.2, 80 mM TEA-sulfate, 0.6 mM TEA-EGTA. Reprinted from Jabůrek et al. [22].

4. The solute carrier model of Kunji and coworkers

It is essential to integrate the UCPs with the mitochondrial solute carrier family. Given the lack of crystal structure of the UCPs, can anything be learned from sequence information? Kunji and coworkers [11] have provided an elegant answer to this question that is particularly useful in considering UCPn function. They reasoned that residues involved in the transport mechanism are likely to be symmetrical, whereas residues involved in substrate binding will be asymmetrical. They then scored the symmetry of residues in the 3 homologous repeats to identify the substrate-binding sites and the surface salt bridge networks involved in the transport mechanism. This analysis also provided clues to the chemical identities of substrates for a given porter.

The model successfully recapitulates properties of the adenine nucleotide transporter (ANT) that had been identified using other techniques, including molecular dynamics [49–51]. During the transport cycle, the ANT forms the cytoplasmic and matrix states in which the substrate-binding site of the carrier is open to the mitochondrial intermembrane space and matrix, respectively. ADP and ATP each bind to 3 sites on the even-numbered helices, and the binding cavity is located near the middle of the membrane. Interconversion of the two states via a transition intermediate leads to substrate translocation.

The method also leads to a number of predictions for UCP [11]. Residues in the cavity region of UCP are highly symmetrical and there are few conserved asymmetric residues. There are no hydrophobic asymmetric residues in the cavities of UCPs, as was observed in the carnitine/acylcarnitine transporter, indicating that FAs are not the intended substrates or that FAs are not transported through the central cavity. Most mitochondrial transporters operate according to a strict exchange mechanism, and Robinson, et al. [11] conclude, “Notably, the uncoupling proteins are predicted to be strict exchangers also.” The net result of their analysis is that the intended substrates of UCPs are likely to be small carboxylic or keto acids, transported in symport with protons.

It is safe to say that no experimental data support such a transport mechanism for the UCPs. Our substrate screening for UCP1 identified exclusively unipolar monovalent anions as substrates [15]. The UCPs are strict uniporters and have never been observed to catalyze electroneutral exchange or proton symport. This discrepancy does not mean that the Kunji approach is wrong. Instead, it conveys the very important information that the UCPs do not use the transport mechanism common to other members of the family and described by the model. It also suggests, as we proposed [18], that the UCPs do not use the central cavity for transport; rather, the anions are transported along the protein-lipid interface. As noted earlier, D28 in UCP1, which lies near the center of the membrane [11], is a candidate for the polar group responsible for the energy well used by anions.

There is further evidence for the view that transport via UCPn does not use the central cavity. The Kunji model describes solute transport very well; however, it does not describe or address an important non-canonical function of these carriers. ANT, for example, mediates a FA-dependent, protonophoretic uncoupling that is inhibited by carboxyatractyloside (reviewed by Skulachev [52]). Like the UCPs, the ANT contains no hydrophobic asymmetric residues in the cavities, nor is there any evidence for involvement of proton-anion symport in the uncoupling activity. The Kunji model also does not describe the uncoupling catalyzed by the aspartate/ glutamate antiporter or the dicarboxylate carrier [52]. From this, we conclude that if the FA anion is the transported species responsible for uncoupling by these carriers or by UCPs, it must be transported at a different location on the protein.

In summary, the Kunji model [11] is an excellent description of the primary transport functions of the mitochondrial solute carrier family. It does not account for FA-dependent uncoupling by the ANT, the aspartate/ glutamate antiporter, the dicarboxylate carrier, or the UCPs. Moreover, the Kunji analysis leads us to infer that transport of anions, including the FA anion, by these proteins takes place outside the central cavity containing the substrate binding sites. Transport of protons through the central cavity seems particularly unlikely for the uncoupling solute carriers such as ANT. The fact that FA-dependent uncoupling by ANT is inhibited by carboxyatractyloside suggests that uncoupling by the solute carriers is regulated by conformational changes occurring during the solute exchange. The corresponding regulation in the UCPs is mediated by conformational changes induced by nucleotide binding. The presumed effect of these conformational changes is to remove the polar group(s) that form the energy well for anion transport at the protein-lipid interface. Our overall conclusion is that the UCPs transport no solutes by the Kunji mechanism. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the UCPs evolved from the uncoupling solute carriers, taking advantage of the existing, regulated uncoupling function and dropping the solute transport function.

5. Summary and future directions

The fatty acid cycling model has the singular advantage of explaining in parallel the translocation of both anions and protons by the UCPs. The proton uniport model has the corresponding disadvantage that it does not include an explanation of anion uniport. Nevertheless, it cannot be said that either model can be definitively confirmed or rejected at present. How can this conundrum be resolved? It would be helpful to obtain crystal structure of the UCPs, but it is not entirely clear that this will solve the problem of mechanism. A potentially valuable approach that has not yet been attempted is to examine more closely the uncoupling function of the adenine nucleotide exchanger, whose solute transport function has been well worked out ([11] and references therein). For example, can molecular dynamics simulations [50,51] identify which central residues move back-and-forth to the protein-lipid interface as an aid to identifying the source of the energy well for FA anion transport on ANT? Does ANT uncoupling exhibit flux-voltage profiles that are similar to UCP?

Compounds arising from increased reactive oxygen species production including lipid peroxidation have been shown to increase uncoupling in isolated mitochondria ([29, 41] and references therein). This ability led to the suggestion of a feedback suppression of oxidative stress through activation of uncoupling [29,41]. This area needs further exploration. For example, the mechanism by which lipid peroxidation products “activate” UCPs is unknown. The interesting finding that induction of carbon-centered radicals leads to increased uncoupling of kidney mitochondria [41] raises several major questions. For example, it is not clear which protein is being affected by this treatment, and the observed total blockade of uncoupling by carboxyatractylate suggests that it is ANT rather than UCP. Moreover, a plausible scenario that has not been investigated is that lipid peroxidation is followed by production of hydroperoxy-FAs through the action of certain phospholipase A2 isoforms, which occurs rapidly in mitochondria. Both PUFAs and hydroperoxy-FAs that might be cleaved off, in turn, are excellent substrates for uncoupling by the UCPs [29,32,33].

There are profound issues of physiology which are not discussed in this review. We really don't know what UCP1 is doing in thymocytes [7], skin [12], brain, [13] and pancreatic β-cells [14]. And what are the physiological functions of UCP2-5? It is not often recognized that all the UCPs are extremely sluggish in their transport function. UCP1 provides abundant heat only because it is expressed at very high amounts in brown adipose tissue mitochondria. UCP2-5 expression levels are low, raising the question of their function. Can such a weak effect (optimistically 1 mV depolarization) lead to reduced superoxide production in vivo [9,10]?

All of these problems are amenable to experimental resolution, and it is hoped that this brief and focused review will stimulate further research on this fascinating group of transport proteins.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the grant No. 303/07/0105 from the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic; ME09018 from the Czech Ministry of Education, and AV0Z50110509 from the Academy of Sciences (P.J.) and by grant HL067842 from the National Institutes of Health (K.G.).

Abbreviations

- ANT

adenine nucleotide transporter, i.e. ADP/ATP carrier

- BLM

bilayer (black) lipid membrane

- FA(s)

fatty acid(s)

- FAOOH or FAOOH-COOH

fatty acid hydroperoxides

- PUFAs

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- PUMPn

plant uncoupling mitochondrial protein, isoform n

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SPQ

6-methoxy-N-(3-sulfopropyl)-quinolinium

- TEA

tetraethyl ammonium

- TES

N-tris(hydroxymethyl)-methylamino-ethanesulfonic acid

- UCP, UCPn

any uncoupling protein, isoform n

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6. References

- [1].Hanák P, Ježek P. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins and phylogenesis-UCP4 as the ancestral uncoupling protein. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:137–41. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ježek P, Ježek J. Sequence anatomy of mitochondrial anion carriers. FEBS Lett. 2003;534:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03779-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ježek P, Žáčka M, Růžička M, Škobisová E, Jabůrek M. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins – facts and fantasies. Physiol. Res. 2004;53(S1):S199–S211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ježek P, Engstová H, Žáčková M, Vercesi AE, Costa ADT, Arruda P, Garlid KD. Fatty acid cycling mechanism and mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1365:319–27. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ježek P. Fatty acid interaction with mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1999;31:457–66. doi: 10.1023/a:1005496306893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nicholls DG. The physiological regulation of uncoupling proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Porter RK. Uncoupling protein 1: a short-circuit in the chemiosmotic process. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2008;40:457–61. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Klingenberg M, Echtay KS. Uncoupling proteins: the issues from a biochemist point of view. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1504:128–43. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nedergaard J, Cannon B. The `novel' `uncoupling' proteins UCP2 and UCP3: what do they really do? Pros and cons for suggested functions. Exp. Physiol. 2003;88:65–84. doi: 10.1113/eph8802502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Krauss S, Zhang CY, Lowell BB. The mitochondrial uncoupling-protein homologues. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:248–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Robinson AJ, Overy C, Kunji ERS. The mechanism of transport by mitochondrial carriers based on analysis of symmetry. Proc. Acad. Natl. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:17766–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809580105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mori S, Yoshizuka N, Takizawa M, Takema Y, Murase T, Tokimitsu I, Saito M. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008;128:1894–1900. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lengacher S, Magistretti PJ, Pellerin LJ. Quantitative rt-PCR analysis of uncoupling protein isoforms in mouse brain cortex: methodological optimization and comparison of expression with brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:780–788. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000122743.72175.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sale MM, Hsu FC, Palmer ND, Gordon CJ, Keene KL, Borgerink HM, Sharma AJ, Bergman RN, Taylor KD, Saad MF, Norris JM. The uncoupling protein 1 gene, UCP1, is expressed in mammalian islet cells and associated with acute insulin response to glucose in African American families from the IRAS Family Study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2007;30:7–1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ježek P, Garlid KD. New substrates and competitive inhibitors of the Cl− translocating pathway of the uncoupling protein of brown adipose tissue mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:19303–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ježek P, Orosz DE, Garlid KD. Reconstitution of the uncoupling protein of brown adipose tissue mitochondria: Demonstration of GDP-sensitive halide anion uniport. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:19296–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ježek P, Orosz DE, Modrianský M, Garlid KD. Transport of anions and protons by the mitochondrial uncoupling protein and its regulation by nucleotides and fatty acids: A new look at old hypotheses. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:26184–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Garlid KD, Orosz DE, Modrianský M, Vassanelli S, Ježek P. On the mechanism of fatty acid-induced proton transport by mitochondrial uncoupling protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2615–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ježek P, Modrianský M, Garlid KD. Inactive fatty acids are unable to flip-flop across the lipid bilayer. FEBS Lett. 1997;408:161–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ježek P, Modrianský M, Garlid KD. A structure activity study of fatty acid interaction with mitochondrial uncoupling protein. FEBS Lett. 1997;408:166–70. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ježek P, Borecký J. The mitochondrial uncoupling protein may participate in futile cycling of pyruvate and other monocarboxylates. Amer. J. Physiol. 1998;275:C496–504. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jabůrek M, Vařecha M, Ježek P, Garlid KD. Alkylsulfonates as probes of uncoupling protein transport mechanism. Ion pair transport demonstrates that direct H+ translocation by UCP1 is not necessary for uncoupling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:31897–905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jabůrek M, Vařecha M, Gimeno RE, Dembski M, Ježek P, Zhang M, Burn P, Tartaglia LA, Garlid KD. Transport function and regulation of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins 2 and 3. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26003–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ježek P, Costa ADT, Vercesi AE. Evidence for anion translocating plant uncoupling mitochondrial protein (PUMP) in potato mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32743–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ježek P, Costa ADT, Vercesi AE. Reconstituted plant uncoupling mitochondrial protein (PUMP) allows for proton translocation via fatty acid cycling mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24272–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Echtay KS, Brand MJ. Coenzyme Q induces GDP-sensitive proton conductance in kidney mitochondria. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2001;29:763–8. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Skulachev VP. Fatty acid circuit as a physiological mechanism of uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 1991;294:158–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80658-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Žáčková M, Škobisová E, Urbánková E, Ježek P. Activating ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inhibitory purine nucleotides are high affinity ligands for novel mitochondrial uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20761–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jabůrek M, Miyamoto S, Di Mascio P, Garlid KD, Ježek P. Hydroperoxy fatty acid cycling mediated by mitochondrial uncoupling protein UCP2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:53097–102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Urbánková E, Voltchenko A, Pohl P, Ježek P, Pohl EE. Transport kinetics of uncoupling proteins: Analysis of UCP1 reconstituted in planar lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:32497–500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Beck V, Jab rek M, Breen EP, Porter RK, Ježek P, Pohl EE. A new automated technique for the reconstitution of hydrophobic proteins into planar bilayer membranes. Studies of human recombinant uncoupling protein 1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:474–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Beck V, Jabůrek M, Demina T, Rupprecht A, Porter RK, Ježek P, Pohl EE. High efficiency of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the activation of human uncoupling protein 1 and 2 reconstituted in planar lipid bilayers. FASEB J. 2007;21:1137–44. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7489com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rupprecht A, Beck V, Ninnemann O, Jab rek M, Trimbuch T, Klishin SS, Ježek P, Skulachev VP, Pohl EE. Role of the transmembrane potential in the mitochondrial membrane proton leak. Biophys. J. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schulten Z, Schulten K. A model for the resistance of the proton channel formed by the proteolipid of ATPase. Eur. Biophys. J. 1985;11:149–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00257393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Feniouk BA, Kozlova MA, Knorre DA, Cherepanov DA, Mulkidjanian AY, Junge W. The proton-driven rotor of ATP synthase: ohmic conductance (10 fS), and absence of voltage gating. Biophys. J. 2004;86:4094–109. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.036962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Smondyrev AM, Voth GA. Molecular dynamics simulation of proton transport near the surface of a phospholipid membrane. Biophys. J. 2002;82:1460–8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75500-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Till MS, Essigke T, Becker T, Ullmann GM. Simulating the proton transfer in gramicidin A by a sequential dynamical Monte Carlo method. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:13401–10. doi: 10.1021/jp801477b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Akinaga Y, Hyodo SA, Ikeshoji T. Lattice Boltzmann simulations for proton transport in 2-D model channels of Nafion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008;10:5678–88. doi: 10.1039/b805107k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yi M, Cross TA, Zhou HX. Conformational heterogeneity of the M2 proton channel and a structural model for channel activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:13311–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906553106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Echtay KS, Winkler E, Bienengraeber M, Klingenberg M. Site-directed mutagenesis identifies residues in uncoupling protein (UCP1) involved in three different functions. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3311–7. doi: 10.1021/bi992448m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Murphy MP, Echtay KS, Blaikie FH, Asin-Cayuela J, Cochemé HM, Green K, Buckingham J, Tailor ER, Hurrell F, Hughes G, Miwa S, Cooper CE, Svistunenko DA, Smith RAJ, Brand M. Superoxide activates uncoupling protein by generating carbon-centered radicals and initiating lipid peroxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:48534–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308529200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Garlid KD, Beavis AD, Ratkje SK. On the nature of ion leaks in energy-transducing membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;976:109–20. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(89)80219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sun X, Garlid KD. On the mechanism by which bupivacaine conducts protons across the membranes of mitochondria and liposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:19147–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fujitani Y, Bedeaux D. A molecular theory for nonohmicity of the ion leak across the lipid-bilayer membrane. Biophys. J. 1997;73:1805–14. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Krishnamoorthy G, Hinkle PC. Non-ohmic proton conductance of mitochondria and liposomes. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1640–5. doi: 10.1021/bi00303a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Garlid KD. Chemiosmotic Theory. In: Carafoli E, editor. Encylopedia Biol. Chem. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wojtczak L, Wieckowski MR, Schönfeld P. Protonophoric activity of fatty acid analogs and derivatives in the inner mitochondrial membrane: a further argument for the fatty acid cycling model. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;357:76–84. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nicholls DG, Locke RM. Thermogenic mechanisms in brown fat. Physiol. Rev. 1984;64:1–64. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Johnston JM, Khalid S, Sansom MSP. Conformational dynamics of the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier: a simulation study. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2008;25:506–17. doi: 10.1080/09687680802459271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wang Y, Tajkhorshid E. Electrostatic funneling of substrate in mitochondrial inner membrane carriers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9598–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801786105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Dehez F, Pebay-Peyroula E, Chipot C. Binding of ADP in the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier is driven by an electrostatic funnel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12725–33. doi: 10.1021/ja8033087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Skulachev VP. Anion carriers in fatty acid-mediated physiological uncoupling. J Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1999;31:431–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1005492205984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]