Abstract

Parallel language activation in bilinguals leads to competition between languages. Experience managing this interference may aid novel language learning by improving the ability to suppress competition from known languages. To investigate the effect of bilingualism on the ability to control native-language interference, monolinguals and bilinguals were taught an artificial language designed to elicit between-language competition. Partial activation of interlingual competitors was assessed with eye-tracking and mouse-tracking during a word recognition task in the novel language. Eye-tracking results showed that monolinguals looked at competitors more than bilinguals, and for a longer duration of time. Mouse-tracking results showed that monolinguals’ mouse-movements were attracted to native-language competitors, while bilinguals overcame competitor interference by increasing activation of target items. Results suggest that bilinguals manage cross-linguistic interference more effectively than monolinguals. We conclude that language interference can affect lexical retrieval, but bilingualism may reduce this interference by facilitating access to a newly-learned language.

Keywords: language processing, bilingualism, language interference, language learning, eye-tracking, mouse-tracking

1. Introduction

There is substantial variability in individual ability to acquire a second or third language, and many learners do not achieve native-like proficiency, particularly later in life (Birdsong, 2006; Birdsong, 2009). Successful acquisition depends not only on learning new words and grammar, but also on the ability to retrieve words from memory during language use. Learning outcomes may be improved by ensuring that words, once acquired, can be retrieved effectively. One obstacle to word retrieval in a new language is competition from similar-sounding words in one’s native language. Cross-linguistic interference is common in bilinguals (Bijeljac-Babic, Biardeau, & Grainger, 1997; Duyck, Assche, Drieghe, & Hartsuiker, 2007; Schwartz & Kroll, 2006; van Heuven, Dijkstra, & Grainger, 1998; Voga & Grainger, 2007), and as a result bilinguals may develop mechanisms to control competition more effectively than monolinguals. We propose that the ability to manage competition from other languages during novel language use is improved in bilinguals relative to monolinguals due to previous linguistic experience.

While listening to speech in a new language, words in other known languages can become activated and compete for selection. Speech unfolds over time, and words that sound similar to the input can become partially activated and interfere with selection of the target word (Allopenna, 1998; Tanenhaus, Magnuson, Dahan, & Chambers, 2000). For example, upon hearing the /k/ at the onset of ‘candle,’ an English speaker initially co-activates ‘candy’ before converging on the target. If ‘candy’ is not suppressed when it becomes inconsistent with the unfolding input, it can interfere with target processing. This interference is especially pronounced when the competitors are of higher lexical frequency than the target (Magnuson, Tanenhaus, Aslin, & Dahan, 2003), as is typically the case when native-language words compete with words in a novel language. If interference from native-language competitors can be mitigated, comprehension in the new language may be improved.

Bilinguals have more potential competitor words to suppress compared to monolinguals; this increase in competitor words may provide bilinguals with more experience managing competition, yielding an advantage in novel-language speech comprehension. Bilinguals activate words that overlap with auditory input in either language (Blumenfeld & Marian, 2007; Marian & Spivey, 2003; Marian, Spivey, & Hirsch, 2003; Spivey & Marian 1999), so that when a Spanish-English bilingual hears the /k/ sound in ‘candle,’ they co-activate ‘car’ and ‘candy’ as an English monolingual would, but they also co-activate ‘casa’ and ‘cabeza’ in Spanish. Word recognition becomes more difficult when the number of competitors increases (Luce & Pisoni, 1998), and bilinguals may adapt to the increased demands by augmenting their ability to suppress irrelevant information. Experience suppressing irrelevant words is thought to contribute to bilinguals’ improved cognitive control across the lifespan compared to monolinguals (Bialystok, 1999, 2007; Bialystok, Craik, Klein, & Viswanathan, 2004; Costa, Hernández, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2008). Bilinguals may thus be better equipped to manage native-language interference during novel-language processing, which could facilitate access to novel-language words.

Bilinguals’ vocabulary knowledge in a newly-learned language surpasses that of monolinguals with comparable training (Cenoz, 2003; Cenoz & Valencia, 1994; Kaushanskaya & Marian, 2009a,b; Keshavarz & Astaneh, 2004; Sanz, 2000; Thomas, 1992; van Hell & Mahn, 1997), but this advantage could be attributed to either better word learning or easier access to learned words in bilinguals. Learning and access are difficult to disentangle, as failure in either step produces the same result—an inability to retrieve the target word. In order to specifically investigate word retrieval in bilingual and monolingual language learners, the present study took a different approach compared to traditional language learning studies. Instead of comparing bilinguals’ and monolinguals’ knowledge of a novel language after a fixed training protocol, all participants were trained up to a performance criterion to ensure that novel words had been acquired. Retrieval difficulty was manipulated by testing participants’ ability to manage competition between languages during spoken comprehension of the newly-learned language. The extent to which competitors interfered with target processing provided an indicator of difficulty accessing novel language words.

Since lexical access during spoken word comprehension occurs over time, between-language competition was assessed using two online measures of lexical processing: eye-tracking and mouse-tracking. Both techniques can be used to covertly measure how temporal processing of a target is affected by competitors in a visual display. Competing items interfere with target processing because the lexical items they depict resemble the target (e.g., phonological overlap), and this similarity causes participants to visually fixate and manually approach competitors more than unrelated control items.

Eye-movements are closely time-locked to relevant features of the input (Cooper, 1974; Tanenhaus, Magnuson, & Dahan, 2000), and are executed without conscious awareness. As a result, they have been used extensively to investigate the timecourses of both word (Allopenna, Magnuson, & Tanenhaus, 1998; Blumenfeld & Marian, 2007; Marian & Spivey, 2003) and sentence processing (Altmann, 1998; Chambers & Cooke, 2009). However, one limitation of eye-tracking is that visual saccades are inherently all-or-nothing events. Continuous changes in item activation over time are inferred by averaging across multiple discrete looks to candidate objects in a display across trials and participants. In contrast, perceptual-motor hand movements are continuous, graded responses (Freeman & Ambady, 2010), and can be affected by sub-threshold processes, so that deviations in smooth trajectories are observed even in the absence of visual saccades to a competitor. It has been shown that movements of the hand are executed contiguously with cognitive processing (Shin & Rosenbaum, 2002), and that fine adjustments can be made in midflight as information about a visual scene is processed (Goodale, Pelisson, & Prablanc, 1986; Song & Nakayama, 2008). The resulting trajectory can be conceptualized as a record of a gradual decision process that converges on one of many attractors in a two-dimensional space (Spivey, Grosjean, & Knoblich, 2005). Although mouse-tracking has only recently been used to inform psycholingusitic processing, it has already proven valuable for investigating the activation of phonological competitors (Spivey, Grosjean, & Knoblich, 2005), object categorization (Dale, Kehoe, & Spivey, 2007), and aspects of syntactic processing (Farmer, Cargill, Hindy, Dale, & Spivey, 2005).

By combining eye-tracking and mouse-tracking, we are able to investigate the time-course and the pattern of cross-linguistic interference and resolution in monolinguals and bilinguals. We predict that bilinguals’ extensive experience managing between-language competition and documented cognitive control advantages will improve their ability to manage cross-linguistic interference after learning a novel language. Specifically, it is expected (1) that monolinguals will look at native-language competitors more often and for a longer duration of time than bilinguals, and (2) that monolinguals’ mouse movement trajectories will show more attraction towards native-language competitors relative to those of bilinguals.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Twelve bilingual Spanish-English speakers and twelve monolingual English speakers completed the experiment. (Four additional participants were tested but were not included in the analyses due to their failure to learn the new language to criterion during the training phase of the study.) Bilinguals had acquired their second language early in life (M=3.83 years, SE=0.78) and were highly proficient in both English and Spanish; language history was obtained using the Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (Marian, Blumenfeld, & Kaushanskaya, 2007) and is summarized in Table 1. Monolinguals and bilinguals did not differ in performance IQ (Weschler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, block design and matrix reasoning subtests; PsychCorp, 1999), English vocabulary size (Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test III; Dunn & Dunn, 1997), working memory (Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, digit span subtest; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1999), or phonological working memory (CTOPP, nonword repetition subtest), all p’s>0.05. Bilinguals' Spanish vocabulary was also assessed (Test de Vocabulario en Imagenes Peabody; Dunn, Ludo, Padilla, & Dunn, 1986). Participant demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Monolingual and Bilingual Participant Demographics

| Demographics | Monolingual English | Bilingual Spanish-English | t(22) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | |||

| Age (years) | 19.75 | 0.95 | 25.83 | 2.94 | 1.97 | ns |

| Education (years) | 13.92 | 0.64 | 15.73 | 0.68 | 1.94 | ns |

| WASI (performance IQ) | 103.33 | 2.44 | 103.75 | 2.22 | 0.13 | ns |

| WASI (percentile) | 58.17 | 6.05 | 59.17 | 5.51 | 0.12 | ns |

| Digit Span (percentile) | 72.50 | 7.91 | 68.25 | 5.96 | 0.43 | ns |

| Nonword Repetition (percentile) | 46.50 | 5.79 | 60.83 | 6.45 | 1.65 | ns |

| PPVT-III (percentile) | 78.00 | 4.90 | 66.33 | 5.55 | 1.57 | ns |

| L2 acquisition age (years) | 3.83 | 0.78 | ||||

| Daily L2 exposure (percentage) | 25.33 | 3.43 | ||||

| Self-rated L2 speaking proficiency (scale 1–10) | 7.25 | 0.35 | ||||

| Self-rated L2 reading proficiency (scale 1–10) | 7.08 | 0.44 | ||||

Note: WASI = Weschler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; PPVT-III = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test III; L2 = second language, according to proficiency.

2.2. Stimuli and Materials

Stimuli consisted of black and white line drawings and represented two-syllable English words with stress on the first syllable; none of the words were English-Spanish cognates. Twenty-four drawings were selected based on high naming consistency norms by native English speakers (N=34, none participated in the current study). No participants experienced difficulty naming the objects in English at the conclusion of the study.

Twenty-four words were created in an artificial language named Colbertian1. The words were recorded by a female speaker of Standard American English and were constructed to follow phonotactic rules of English and Spanish. The twenty-four words did not differ in English and Spanish wordlikeness ratings by bilingual speakers (N=5), or in English and Spanish phonological neighborhood size2 (p’s > 0.05). Each of the twenty-four pictures was assigned a Colbertian translation, which overlapped phonologically with the English name of another picture (e.g., acorn is translated as shundo, which overlaps with the English word shovel). These overlapping Colbertian-English pairs were used to assess phonological competition between languages; a complete list of all pairings is presented in Appendix A. English competitor words and targets’ English translations did not differ (p’s>0.05) in word frequency (SUBTLEXUS; Brysbaert & New, 2009), concreteness, familiarity, imageability (MRC Psycholinguistic Database; Coltheart, 1981), or number of orthographic (Duyck, Desmet, Verbeke, & Brysbaert, 2004) or phonological (N-Watch; Davis, 2005) neighbors. Targets’ Spanish translations and competitors’ Spanish translations did not differ (p’s>0.05) in word frequency (LEXESP; Sebastián-Gallés, Martí, Cuetos, & Carreiras, 1996), or in number of orthographic or phonological neighbors (BuscaPalabras; Davis & Perea, 2005).

Eye movements were recorded with a head-mounted ISCAN eyetracker system. A scene camera captured the participant's field of view, and an infrared camera allowed the software to track the participant's pupil and corneal reflection. The participant’s gaze was indicated by crosshairs superimposed over the scene camera's output and recorded to digital video. Mouse-movements, accuracy, and reaction time were recorded using Psyscope (Cohen, MacWhinney, Flatt, & Provost, 1993), which also controlled stimuli presentation.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Learning the New Language

The learning paradigm was designed to equate novel language attainment across monolingual and bilingual groups, so that any observed differences in between-language competition could not be attributed to novel-language proficiency. Participants were first familiarized with the 24 pictures and their translations in Colbertian. A picture appeared on a computer screen and 500ms later the participant heard the Colbertian word over headphones; the participant was instructed to repeat the word aloud. The picture remained on the screen 1500ms after audio presentation, and was followed by an inter-trial interval of 1000ms. The 24 pictures were presented in four random orders. A two-alternative forced-choice recognition test, during which each picture appeared as a target once, ensured that participants were familiar with Colbertian before production training began. In the recognition test, monolinguals and bilinguals did not differ in accuracy or reaction time, p’s>0.1 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Learning the Novel Language

| Monolingual English | Bilingual Spanish-English | Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | ||

| Training – Recognition Task | |||||

| Accuracy | 92.10% | 0.02% | 95.80% | 0.01% | t(21)=1.35, ns |

| Reaction Time (ms) | 2024 | 89.7 | 2089 | 65.1 | t(21)=0.60, ns |

| Training – Production Task | |||||

| First Block Accuracy | 13.54% | 0.03% | 25.00% | 0.05% | t(22)=1.84, p=0.08 |

| Time to Learn (Blocks) | 15.25 | 1.23 | 13.5 | 1.81 | t(22)=0.80, ns |

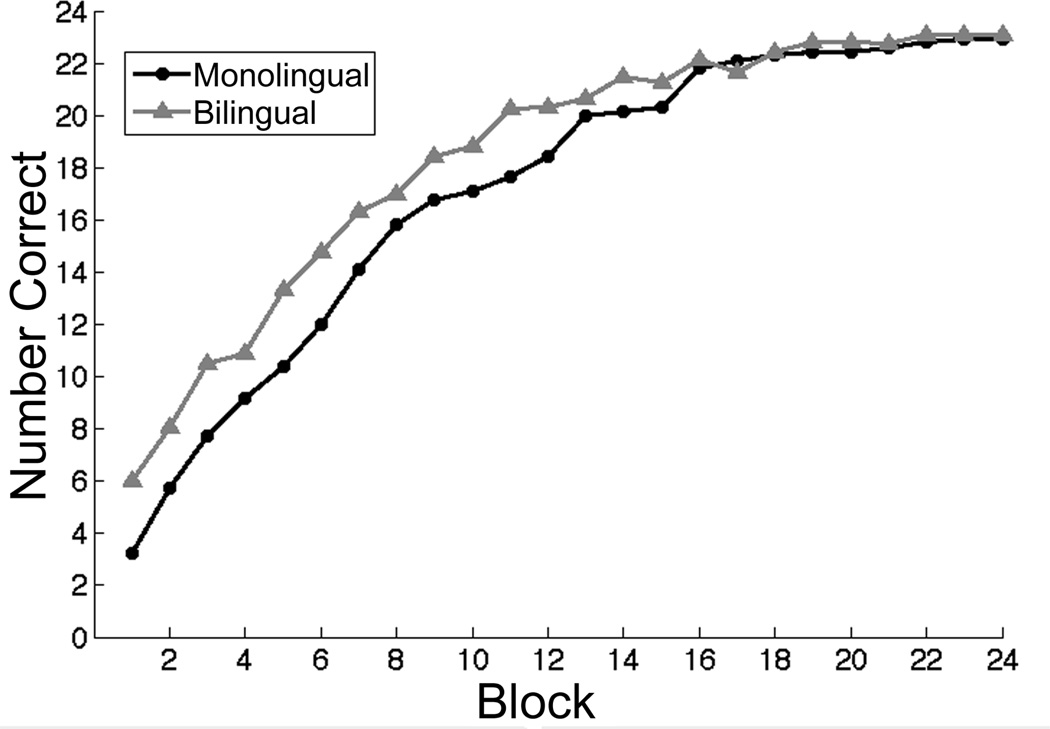

As production is more difficult than recognition in a new language, participants were trained to produce the Colbertian names of pictures to ensure that their knowledge of the language would be sufficient for the subsequent recognition task testing English-interference. During production training, a picture appeared on the screen and the participant was instructed to name the object aloud in Colbertian. The participant's response was recorded with a microphone. Trials timed out after 4000ms without a response. Errors were indicated by a beep over headphones, and all trials were followed by audio presentation of the correct object name. In a single training block each picture appeared once in a random order. Training blocks were repeated until a learning criterion was met (90% of the objects named correctly on two consecutive blocks); monolinguals and bilinguals did not differ in the number of blocks required to reach criterion3. Any participant who did not reach criterion after 24 blocks did not advance to the English-interference condition (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Monolingual and bilingual performance learning the new language. Within each block, participants attempted to name all twenty-four items in the new language and received feedback. Blocks were repeated until a learning criterion was reached (90% named correctly on two consecutive blocks). No significant group differences in learning were found after any training block or in final attainment.

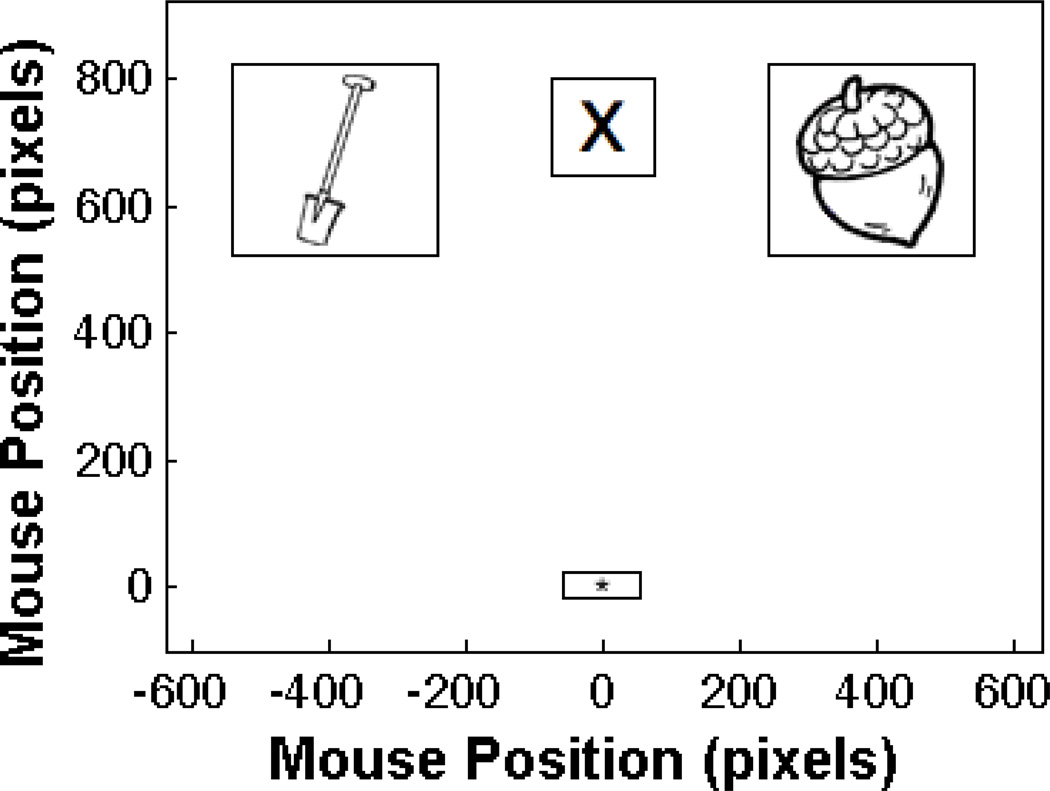

2.3.2. Testing Interference from English

After reaching criterion in the new language, between-language competition was assessed. The participant began each trial by clicking in a small box at the bottom of the screen. Target and distractor pictures appeared on the screen, one in the top left and one in the top right corner, with target position counterbalanced. A red “X” appeared in a box in the top center of the screen (see Fig. 2 for an example trial). After 500ms, the target word in Colbertian was played over headphones. The participant’s instructions were to click the target or, if the target was not present (i.e., filler trials), the red “X”. The trial ended when the participant clicked in one of the three boxes.

Fig. 2.

Sample trial. Participants began each trial by clicking in the small box at the bottom of the screen with an asterisk to reset the mouse cursor position. Upon clicking the box, it disappeared and three boxes appeared at the top of the screen containing a target picture (left or right box), a red ‘X’ (center box, used for filler trials), and a phonological competitor or control picture (left or right box, opposite target). 500ms after trial onset, the name of the target was spoken in the new language over headphones; the trial ended when the participant clicked in one of the three boxes at the top of the screen.

The target was always a word in Colbertian. In 12 Competitor trials, the English name of the distractor phonologically overlapped with the Colbertian name of the target (e.g., target shundo /ʃʌndoʊ/ (picture of an acorn) and competitor shovel /ʃʌvəl/). In 12 matching Control trials, the same targets were paired with non-overlapping control items (e.g. target shundo /ʃʌndoʊ/ and control mushroom /mʌʃru:m/). In 24 filler trials, two novel pictures with no Colbertian translation were shown on the screen. The participant heard a word in Colbertian, but the correct response was to click on the red “X,” as the word matched neither picture. The names of non-target objects (e.g., fummop/shovel and panbo/mushroom) were used in filler trials.

2.4. Data Analysis

Eye-movements were sampled at 30 Hz and coded for looks to target, competitor, and control pictures from 500ms pre-word-onset to 2000ms post-word-onset. Mouse position was sampled by the computer at approximately 60 Hz. Incorrect trials were removed from all analyses (1.6% of trials). One monolingual's mouse-tracking and reaction time data were dropped due to recording difficulties. Mouse-tracking trials with a left-target were flipped horizontally across the midline of the screen. In order to average across trials, movement curves were re-centered to a common origin (0,0) and normalized for duration (Spivey, Grosjean, & Knoblich, 2005). Time normalization involved linear interpolation to resample the x- and y-coordinates of each curve at 101 equally-spaced points in time, separately for competitor and control trials.

3. Results

3.1. Eye-tracking

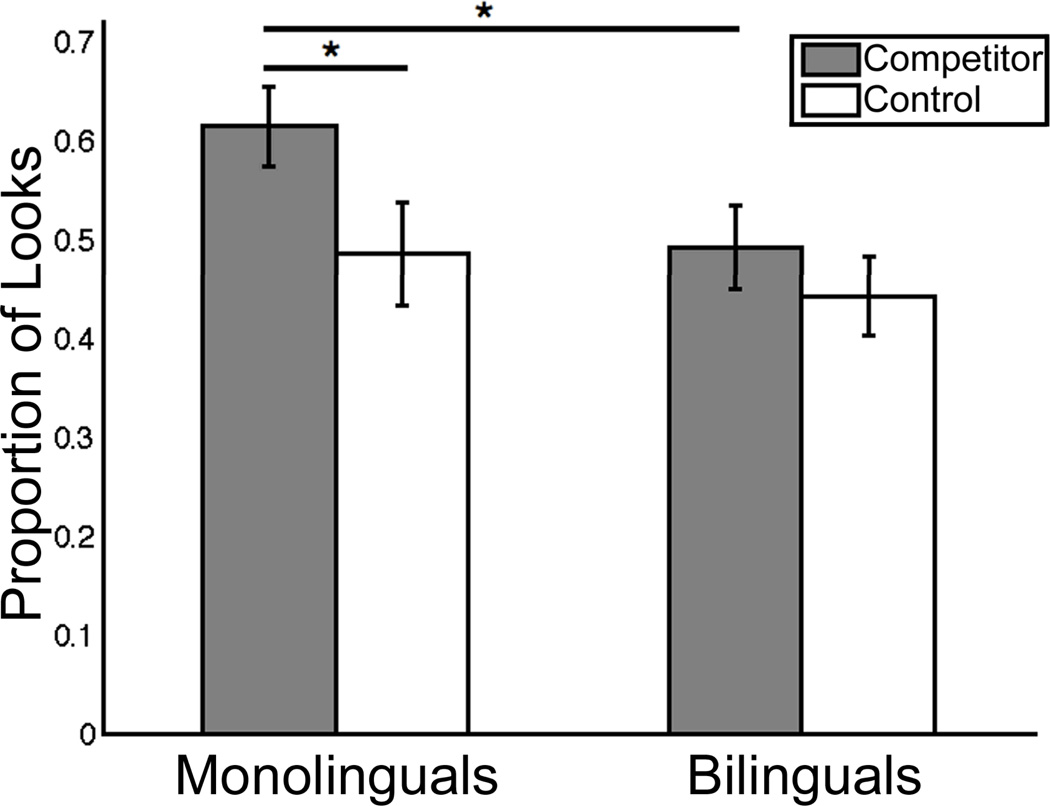

Monolinguals, but not bilinguals, were more likely to fixate between-language competitors than control items, indicating that bilinguals managed competition from a known language more effectively. Time-course analysis revealed that monolinguals looked at competitors more than at control items for a longer duration of time compared to bilinguals, indicating that bilinguals resolved between-language competition earlier. Since the minimum latency to execute a saccade in a visual search task falls between 200–300ms (Viviani, 1990), we analyzed proportion of looks to competitor and control items starting 200ms post-word-onset, and ending 1500ms post-word-onset, at which time fixation curves approached an asymptote. Proportion of looks was analyzed with a 2×2 (Condition [competitor, control] × Group [monolingual, bilingual]) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Condition, F1(1,22)=5.20, p<0.05, partial eta2=0.086, F2(1,22)=3.10, p=0.08, partial eta2=0.033 (Fig. 3), but no main effect of Group, F1(1,22)=3.51, partial eta2=0.074, F2(1,22)=2.47, partial eta2=0.026 and no interaction F1(1,22)=0.82, partial eta2=0.018, F2(1,22)=0.88, partial eta2=0.009. Planned comparisons4 indicated that bilinguals did not differ in looks to competitors (M=0.49, SE=0.04) versus controls (M=0.44, SE=0.04), t(11)=−0.84, p>0.1, d=0.36, but monolinguals looked at competitors (M=0.62, SE=0.04) more than at controls (M=0.49, SE=0.05), t(11)=−2.50, p<0.05, d=0.83. Additionally, monolinguals looked at competitors more than bilinguals, t(22)=2.08, p<0.05, d=0.94 but monolinguals and bilinguals did not differ in looks to controls, t(22)=0.65, p>0.1, d=0.32.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of looks to interlingual competitor and control items from 200–1500ms post word onset. Error bars represent one standard error, and asterisks indicate significance at an alpha of 0.05.

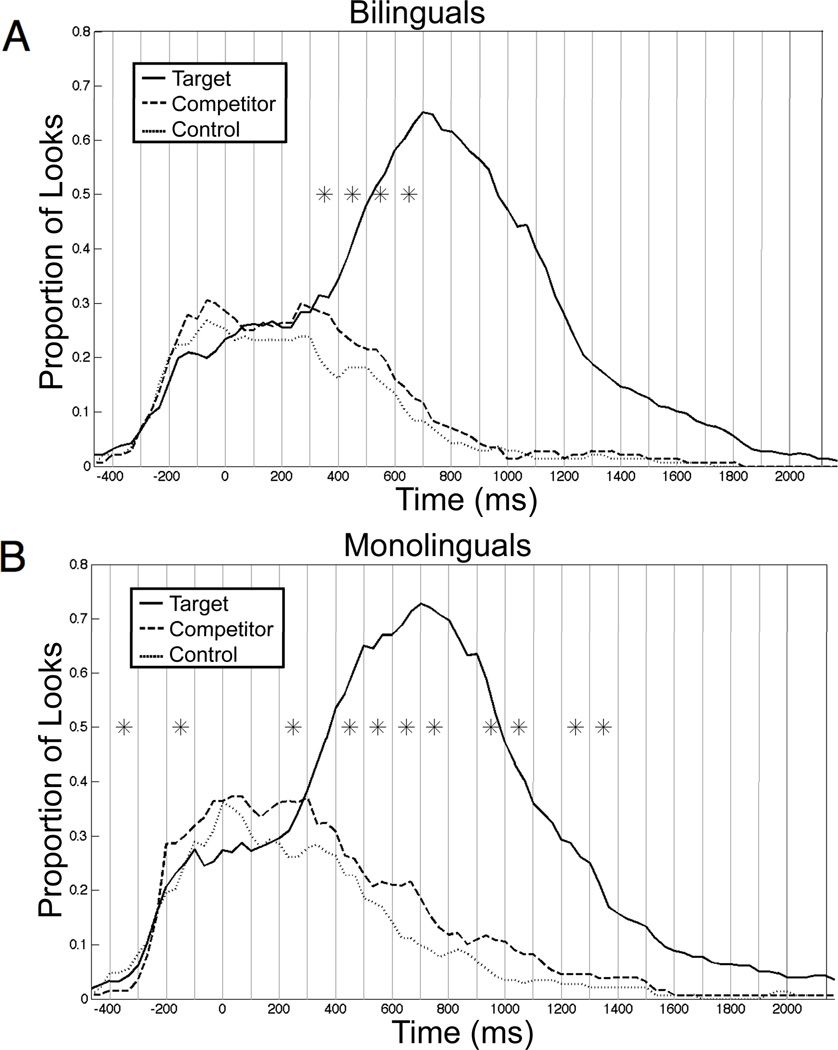

The time-course of competitor activation was examined by calculating eye-tracking fixations in 100ms time windows starting 500ms pre-word-onset. Bilinguals (Fig. 4a) showed more looks to competitors than controls continuously from 300–700ms post-word-onset (all p's<0.05). Monolinguals experienced competitor activation for a longer duration of time (Fig. 4b), with more looks to competitors compared to controls from 200–300ms, 400–800ms, 900–1100ms, and 1200–1400ms post-word-onset (all p's<0.05). Monolinguals also looked at controls more than at competitors from −400 to −300ms pre-word-onset, and looked at competitors more than at controls from −200 to −100ms pre-word-onset (all p’s<0.05). In addition, monolinguals looked at controls more than at targets from −100ms pre-word-onset to 100ms post-word-onset, and looked at competitors more than at targets from −100ms pre-word-onset to 200ms post-word-onset. Bilinguals looked at controls more than at targets from −500 to −300ms, and from −100 to 0ms pre-word-onset, and looked at competitors more than at targets from −200 to 0ms pre-word-onset. Results suggest that while both groups showed activation of the interlingual competitor, competition was resolved earlier in bilinguals, indicating that bilingual experience improves the ability to manage cross-linguistic interference.

Fig. 4.

Bilingual and monolingual eye-tracking fixations. Proportion of looks to competitor and control items were analyzed in 100ms time windows. Bilinguals looked at competitors more than controls contiguously from 300 – 700ms post word onset, and monolinguals looked at competitors more than controls at intervals from 200 – 1400ms post word onset. Asterisks indicate significance at an alpha of 0.05.

3.2. Mouse-tracking

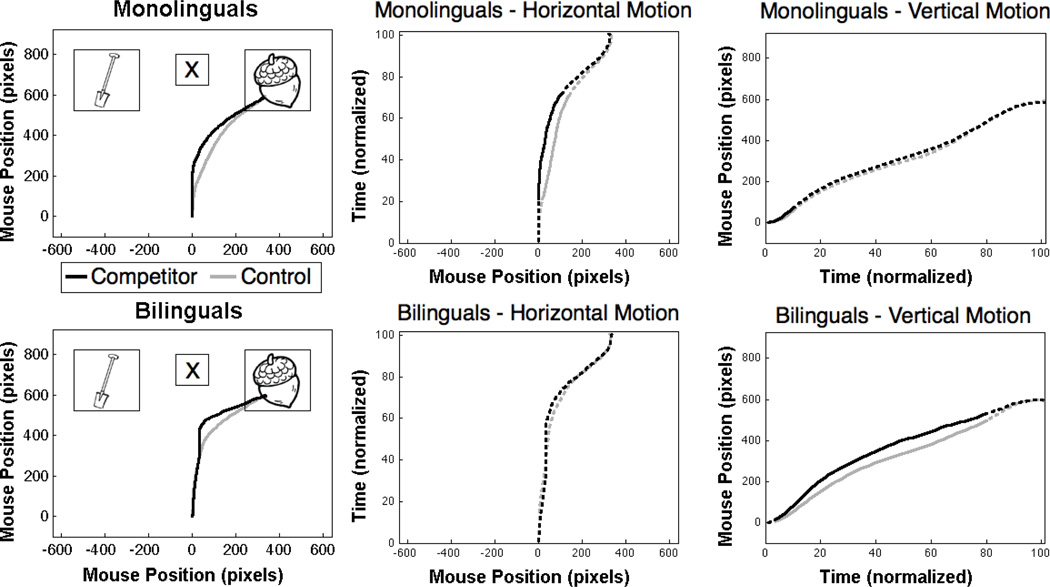

Mouse movement curves reliably diverged between competitor and control conditions in both monolinguals and bilinguals. Notably, the effect of the competitor was realized differently between groups. In monolinguals, competition affected the horizontal motion component, thereby disrupting movement towards the target. In bilinguals, the competitor affected vertical motion, but did not disrupt target approach, suggesting that language experience affects patterns of cross-linguistic competition. Individual mouse movement curves were normalized for duration by re-sampling the time vector at 101 equally spaced intervals and computing x- and y-coordinate vectors by linear interpolation. The x- and y-coordinates, representing horizontal and vertical motion, were analyzed separately (Fig. 5). Competitor and control curves were compared with point-to-point t-tests; a reliable divergence was defined as significant differences on 8 consecutive comparisons (p<0.05) based on a bootstrap criterion from 10,000 simulated experiments (Appendix B, and see Dale, Kehoe, & Spivey, 2007).

Fig. 5.

Results from the mouse-tracking analysis. Lines represent average movement trajectories normalized for duration (left column). The solid line indicates a significant difference between competitor and control curves (p < 0.05); x- (middle column) and y- (right column) components of the movement vector were analyzed separately. Bilinguals show no differences in the x-coordinate, but show a difference in the y-coordinate from the 4th to the 80th segment. Monolinguals show a difference in the x-coordinate from the 21st to the 72nd of 101 segments, and in the y-coordinate from the 2nd to the 10th segments.

Horizontal motion emerges from opposed target- and distractor-attraction, since the attractors pull movement towards opposite sides of the screen (Spivey, Grosjean, & Knoblich, 2005). When the distractor competes with the target, these opposing influences slow target approach. In monolinguals, competitor and control curves diverged in the x-coordinate for 51 consecutive time points (21st–72nd segment, all p’s<0.05), indicating increased competition between the target and the distractor when they overlapped phonologically across languages. Bilinguals did not show an effect of condition on horizontal motion (all p’s>0.05), suggesting that the activations of competitors and controls relative to targets did not differ.

Vertical motion emerges from combined target- and distractor-attraction, since both attractors pull in the same direction (Spivey, Grosjean, & Knoblich, 2005). Monolinguals’ competitor and control curves diverged for 8 consecutive time points in the y-coordinate (2nd–10th segment, all p’s<0.05), while bilinguals’ curves diverged for 76 consecutive time points (4th–80th segment, all p’s<0.05), in both cases due to faster movement upwards in the competitor condition compared to control. The effect of Condition on vertical motion, but not horizontal motion, in bilinguals suggests that although the difference in target and distractor activation was not affected by the presence of a competitor (lack of a horizontal motion effect), there were equivalent increases in activation of the target and of the distractor when a competitor was present. This suggests that bilinguals experienced competition between languages, similarly to monolinguals, but were able to successfully manage competition due to an increase in target activation concurrent with the increase in competitor activation. This increase in target activation was sufficient to offset the competitor’s pull in the x-coordinate. However, the increase in target activation combined with competitor activation had the side effect of increasing overall attraction towards both items in the display (along the y-coordinate) compared to the control condition.

3.3. Accuracy and Reaction Time

Recognition accuracy in the new language was assessed with a 2×2 (Condition [competitor, control] × Group [monolingual, bilingual]) repeated-measures ANOVA. No main effects or interactions were found (all p’s>0.1), likely due to near-ceiling performance for both monolinguals and bilinguals, and in both competitor and control conditions (all accuracies above 97.9%).

Reaction times were obtained for response initiation and target selection, and analyzed separately with 2×2 (Condition [competitor, control] × Group [monolingual, bilingual]) repeated-measures ANOVAs. No main effects or interactions were found for response initiation (all p’s>0.05), suggesting that groups did not differ in response strategy and approached all trials similarly. A significant main effect of Condition was found for target selection, F(1,21)=8.17, p<0.01, where competitor trials (M=1781ms, SE=60ms) took longer than control trials (M=1671ms, SE=44ms), but there was no main effect of Group, F(1,21)=0.04, p>0.1, and no interaction F(1,21)=1.16, p>0.1, suggesting that both groups were affected by the competitor manipulation.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of bilingual experience in managing competition between a known language and a newly-learned language. Bilinguals were found to resolve between-language competition earlier than monolinguals, and to do so in a manner consistent with a target-facilitation account. Results suggest that bilingual experience affects how novel language learners manage activation of multiple languages.

Eye-tracking analyses revealed that monolinguals looked at native language competitors more than bilinguals, and that monolinguals looked at competitors more than controls. The time course of activation showed that both monolinguals and bilinguals experienced early activation of the native-language competitor (as soon as 200ms post-word-onset), though groups differed in efficiency managing between-language competition. While bilinguals resolved competitor activation by 700ms post-word-onset, monolinguals sustained activation of the competitor up to 1400ms post-word-onset. Differences in competitor processing suggest that bilingual experience affects how interference from non-target languages is managed, and may contribute to the emergence of executive control advantages typically found in bilinguals (Bialystok, 1999, 2007; Bialystok, Craik, Klein, & Viswanathan, 2004). The surprising pre-word-onset differences in looks to targets, competitors, and controls were too early to be related to the auditory stimulus, but may indicate an interaction between visual and linguistic information during language co-activation. Before word onset, the visual input alone may have been sufficient to increase activation of competitors due to the similarity between the English label of the competitor image and the Colbertian label of the target image. Notably, by 200ms post-word-onset (the last point at which fixations may be unaffected by the auditory stimulus, since visual saccades take 200ms to plan and execute), any early effects had been terminated, suggesting that early effects did not persist to influence processing of the auditory target.

While eye-tracking showed that monolinguals and bilinguals differed in the time course of between-language competition, mouse-tracking revealed differences in how competition was managed. In monolinguals, increased competitor activation relative to targets curved mouse trajectories away from the target (evidence from horizontal motion). Monolinguals did not move upwards on the computer screen faster in the competitor condition, indicating that they failed to increase target activation to compensate for the competitor (evidence from vertical motion). In sum, parallel activation of the known language, English, interfered with monolinguals’ novel-language processing as between-language cohorts became activated.

In contrast, bilinguals showed no difference in relative activation between conditions, but did show greater combined activation of the target and distractor during the competitor condition. This suggests greater activation of the competitor compared to the control, concurrent with greater activation of the target in the competitor condition compared to the target in the control condition. Bilinguals experienced competition from a known language, but compensated by facilitating the target. This is consistent with recent findings that the bilingual advantage in executive control stems from improved goal maintenance, and not from active competitor inhibition (Colzato et al., 2008). Overall, the mouse-tracking results suggest that extensive bilingual experience improves the ability to retrieve and process targets despite interference during early novel language learning.

Although eye-tracking and mouse-tracking results both indicated that bilinguals manage between-language competition more effectively than monolinguals, no group differences in RT emerged. Since RTs are an outcome-based measure, they are affected both by online processing and by post-perceptual decision processes, and this may have obscured the fine-grained temporal dynamics apparent in the eye-tracking and mouse-tracking data. For instance, in addition to managing interference caused by experimental competitors, participants also needed to globally suppress non-target languages. Bilinguals needed to suppress two other languages during the decision process—the English language that the monolinguals were also suppressing, as well as an entire other language, and this may have obscured group differences in RT.

It is necessary to point out that while there were individual differences in language learning aptitude, these differences were controlled for by using an iterated training paradigm that ended once a proficiency criterion was met. In natural language instruction, where training is constant and final proficiency varies, bilinguals outperform monolinguals in learning novel language vocabulary (Cenoz, 2003; Cenoz & Valencia, 1994; Kaushanskaya & Marian, 2009a,b; Keshavarz & Astaneh, 2004; Sanz, 2000; Thomas, 1992; van Hell & Mahn, 1997), grammar (Klein, 1995; Sanz, 2000; Thomas, 1992), and pragmatic rules (Safont Jorda, 2003). Differences in language transfer (MacWhinney, 2007; Murphy, 2003), metalinguistic awareness, (Jessner, 1999, 2008), and phonological working memory (Papagno & Vallar, 1995) are thought to contribute to the bilingual language learning advantage, but by training participants to a proficiency criterion, the effect of these factors on our results is reduced. We suggest that bilinguals’ ability to control interference contributes to their performance advantage in novel language learning by facilitating word retrieval in the target language. This view is supported by recent findings that bilinguals learn a novel language better than monolinguals when the new language contains rules that conflict with the native language (Kaushanskaya & Marian, 2009b). Bilinguals’ ability to manage conflict between languages is likely affected by several aspects of bilingual experience, including age of second language acquisition, first and second language proficiency, and relative language exposure. The precise roles of these factors on the ability to control language interference should be explored in further research.

We have suggested that bilinguals are better than monolinguals at controlling between-language competition, based on both groups experiencing similar competition from the native language and bilinguals being able to manage this competition more effectively. An alternative explanation is that groups manage competition similarly, but bilinguals experience less competition than monolinguals due to decreased native language activation, since each of a bilingual’s two languages receive less practice than a monolingual’s one. Proficiency in the non-target language has an important influence on parallel language activation (Blumenfeld & Marian, 2007; Jared & Kroll, 2001; Weber & Cutler, 2004), and it is conceivable that bilinguals co-activated English less than monolinguals, resulting in less interference. In the present study, however, this explanation is not sufficient. Monolinguals and bilinguals did not differ on English vocabulary size (p>0.1), and although bilinguals’ language use was divided between English and Spanish, English use predominated. In addition, the mouse-tracking results suggest that the difference between groups was not strictly one of degree, but also one of kind, and involved changes in how interference was managed. If bilinguals were to experience less competition from English than monolinguals but managed it in a similar way, we would have expected the mouse-tracking curves to look qualitatively similar between groups, but with greater divergence towards the competitor in the monolingual group. Instead, we saw that groups reacted to between-language competition differently, with competitor effects emerging in different movement patterns, suggesting different underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, we have shown that bilinguals experience less competition from the native language while processing a newly-learned language compared to monolinguals. We suggest that interference from other languages is one of the reasons why novel language acquisition is more difficult than first-language acquisition (Birdsong, 2006, 2009; MacWhinney, 2007; Rast, 2010). We propose that previous experience using multiple languages hones the ability to control cross-linguistic competition and improves processing of words in a newly-learned language.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants 1R03HD046952 and 1R01HD059858 to VM. The authors would like to thank Anthony Shook, Scott Schroeder, and Sarah Chabal for comments on this work, Amanda Kellogg for recording the materials, and Han-Gyol Yi for assistance with testing.

Appendix A

Target words in Colbertian with translations, competitors, and controls

| Target (Colbertian) |

IPA | Target (English translation) |

Target (Spanish Translation) |

Competitor (English) |

IPA | Control (English) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acrip | ˈeɪkrɪp | easel | caballete | acorn | ˈeɪkɔ:n | mushroom |

| appint | ˈæpɪnt | iron | plancha | apple | ˈæpəl | necklace |

| bakloo | 'bæklu: | necklace | collar | basket | 'bæskət | glasses |

| cattoss | ˈkætɑ:s | pencil | lápiz | candle | ˈkændḷ | iron |

| caddip | ˈkedɪp | elbow | codo | carrot | ˈkerət | garlic |

| eazoond | ˈi:zu:nd | funnel | embudo | easel | ˈi:zəl | zipper |

| eldin | ˈɛldɪn | vacuum | aspiradora | elbow | ˈɛlˌboʊ | scissors |

| fenip | 'fenɪp | carrot | zanahoria | feather | 'feðər | hammer |

| fummawp | ˈfʌmɑ:p | shovel | pala | funnel | ˈfʌnḷ | onion |

| ganteh | ˈgɑntə | scissors | tijera | garlic | ˈgɑɚlɪk | carrot |

| glolay | ˈgloʊle | apple | manzana | glasses | ˈglæsɛz | basket |

| hannawl | ˈhænɑ:l | garlic | ajo | hammer | ˈhæmɚ | feather |

| iyork | ˈajɔ:rk | toilet | inodoro | iron | ˈajɚn | candle |

| lateep | 'læti:p | hammer | martillo | ladder | 'lædər | vacuum |

| munbo | 'mʌnboʊ | zipper | cremallera | mushroom | 'mʌʃru:m | acorn |

| nepri | ˈnepri: | candle | vela | necklace | ˈnekləs | apple |

| unyops | ˈʌnjɑ:ps | parrot | loro | onion | ˈʌnjən | funnel |

| panboe | ˈpænboʊ | mushroom | hongo | parrot | ˈpærət | shovel |

| peftoo | ˈpɛftu: | basket | cesta | pencil | ˈpɛnsəl | toilet |

| simmoz | ˈsɪmɑ:z | ladder | escalera | scissors | ˈsɪzɚz | elbow |

| shundoe | ˈʃʌndoʊ | acorn | bellota | shovel | ˈʃʌvəl | parrot |

| toymeen | ˈtoɪmi:n | glasses | lentes | toilet | ˈtoɪlət | pencil |

| vadip | ˈvædɪp | feather | pluma | vacuum | ˈvækjuəm | ladder |

| zinnul | ˈzɪnʌl | onion | cebolla | zipper | ˈzɪpɚ | easel |

Appendix B

To control for alpha-escalation in the point-to-point comparisons of the mouse-tracking results, a minimal reliable sequence of significant comparisons was established with the bootstrapping simulation of Dale, Kehoe, and Spivey (2007). A simulated “experiment” was performed 10,000 times for each combination of monolinguals/bilinguals and x-/y-coordinates. Model participants (11 for the monolingual simulations and 12 for the bilingual simulations) were constructed based on actual group means and standard deviations of the actual movement curves. The competitor and control curves were compared at each time point, and the longest consecutive sequence of significant t-tests (p<0.05) was recorded for each simulation. The frequency with which a sequence of length N or longer occurred across all simulations was assessed; it was found that a sequence of length 8 occurred with a probability of 0.01 or lower across all group/coordinate combinations, and was selected as a conservative minimum sequence of significant comparisons.

Sequence Frequency in 10,000 Simulated Experiments for Monolinguals and Bilinguals and for X- and Y-Coordinates

| ML – X | ML – Y | BL – X | BL – Y | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Size | % | p | % | p | % | p | % | p |

| 3 | 64 | 3 | <0.05 | 4 | <0.1 | 25 | ||

| 4 | 26 | 0.2 | <0.01 | 0.5 | <0.01 | 5 | ||

| 5 | 10 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.7 | <0.05 | |

| 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | <0.01 | |||

| 7 | 1 | <0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | <0.001 | ||

| 8 | 0.4 | <0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 9 | 0.1 | <0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 10 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

Footnotes

Naming the artificial language simplified explaining the task to participants and made it more engaging. The name Colbertian was chosen in reference to media personality and Northwestern University alum Stephen Colbert who was Homecoming Grand Marshall and Commencement speaker around the time this study was designed and conducted at Northwestern.

Phonological neighbors were defined as single phoneme substitutions, deletions, or additions that yielded an English or Spanish word with frequency greater than 0.34 per million (English: SUBTLEXus, Brysbaert & New, 2009; Spanish: LEXESP; Sebastián-Gallés, Martí, Carreiras, & Cuetos, 2000) as per Davis (2005) and Davis and Perea (2005). There was no difference between phonological neighborhood size in English (M=0.21 neighbors, SE=0.08) and Spanish (M=0.67, SE=0.35), t(23)=1.52, p>0.05.

Overall learning in the first block was low due to the difficulty of novel word production in comparison to recognition, which may have reduced our ability to detect an early difference in learning aptitude between groups. There was a trend for bilinguals to correctly name more words in the first training block (see Table 2), and although attainment rate was in the expected direction, the difference was not significant. A consequence of our closed twenty-four item learning set is that learning rates must decrease over time, as the set of unlearned words shrinks. This flattens attainment curves and minimizes group differences over time.

Failure to reject the null on an F test can mask significant pair-wise comparisons, a phenomenon referred to as nonconsonance (Gabriel, 1969; Hancock & Klockers, 1996; Keppel & Zedeck, 1989). In the current study, planned pair-wise comparisons were carried out based on prior visual world eye-tracking studies (Blumenfeld & Marian, 2007; Chambers & Cooke, 2009; Ju & Luce, 2004; Marian & Spivey, 2003; Weber & Cutler, 2004).

References

- Allopenna P. Tracking the time course of spoken word recognition using eye movements: Evidence for continuous mapping models. Journal of Memory and Language. 1998;38(4):419–439. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann GTM. Ambiguity in sentence processing. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1998;2:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E. Cognitive complexity and attentional control in the bilingual mind. Child Development. 1999;70(3):636–644. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E. Cognitive effects of bilingualism: How linguistic experience leads to cognitive change. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2007;10(3):210–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Craik FI, Klein R, Viswanathan M. Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: Evidence from the Simon task. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):290–303. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijeljac-Babic R, Biardeau A, Grainger J. Masked orthographic priming in bilingual word recognition. Memory & Cognition. 1997;25(4):447–457. doi: 10.3758/bf03201121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong D. Age and second language acquisition and processing: A selective overview. Language Learning. 2006;56:9–49. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong D. Age and the end state of second language acquisition. In: Ritchie W, Bhatia T, editors. New Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld HK, Marian V. Constraints on parallel activation in bilingual spoken language processing: Examining proficiency and lexical status using eye-tracking. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2007;22(5):633–660. [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert M, New B. Moving beyond Kucera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(4):977–990. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenoz J. The additive effect of bilingualism on third language acquisition: A review. International Journal of Bilingualism. 2003;7(1):71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cenoz J, Valencia JF. Additive trilingualism: Evidence from the Basque Country. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1994;15(2):195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CG, Cooke H. Lexical competition during second-language listening: Sentence context, but not proficiency, constrains interference from the native lexicon. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2009;35(4):1029–1040. doi: 10.1037/a0015901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, MacWhinney B, Flatt M, Provost J. PsyScope: An interactive graphic system for designing and controlling experiments in the psychology laboratory using Macintosh computers. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 1993;25(2):257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M. The MRC psycholinguistic database. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A: Human Experimental Psychology. 1981;33(4):497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Colzato LS, Bajo MT, van den Wildenberg W, Paolieri D, Nieuwenhuis S, La Heij W, Hommel B. How does bilingualism improve executive control? A comparison of active and reactive inhibition mechanisms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2008;34(2):302–312. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Hernández M, Sebastián-Gallés N. Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition. 2008;106(1):59–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale R, Kehoe C, Spivey MJ. Graded motor responses in the time course of categorizing atypical exemplars. Memory & Cognition. 2007;35(1):15–28. doi: 10.3758/bf03195938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C. N-Watch: A program for deriving neighborhood size and other psycholinguistic statistics. Behavior Research Methods. 2005;37(1):65–70. doi: 10.3758/bf03206399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Perea M. BuscaPalabras: A program for deriving orthographic and phonological neighborhood statistics and other psycholinguistic indices in Spanish. Behavior Research Methods. 2005;37(4):665–671. doi: 10.3758/bf03192738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra T, van Heuven WJ. The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2002;5(3):175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Duyck W, Assche EV, Drieghe D, Hartsuiker RJ. Visual word recognition by bilinguals in a sentence context: Evidence for non-selective lexical access. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2007;33(4):663–679. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyck W, Desmet T, Verbeke LP, Brysbaert M. WordGen: A tool for word selection and nonword generation in Dutch, English, German, and French. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36(3):488–499. doi: 10.3758/bf03195595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer T, Cargill S, Hindy N, Dale R, Spivey MJ. Streaming x, y coordinates imply continuous interaction during on-line syntactic processing. Proceedings of the 28th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society; 2005. pp. 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J, Ambaddy N. MouseTracker: Software for studying real-time mental processing using a computer mouse-tracking method. Behavior Research Methods. 2010;42(1):226–241. doi: 10.3758/BRM.42.1.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel KR. Simultaneous test procedures—Some theory of multiple comparisons. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1969;40(1):224–250. [Google Scholar]

- Goodale MA, Pélisson D, Prablanc C. Large adjustments in visually guided reaching do not depend on vision of the hand or perception of target displacement. Nature. 1986;320:748–750. doi: 10.1038/320748a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR, Klockars AJ. The quest for alpha: Developments in multiple comparison procedures in the quarter century since Games (1971) Review of Educational Research. 1996;66(3):269–306. [Google Scholar]

- Jared D, Kroll JF. Do bilinguals activate phonological representations in one or both of their languages when naming words? Journal of Memory and Language. 2001;44(1):2–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jessner U. Metalinguistic awareness in multilinguals: Cognitive aspects of third language learning. Language Awareness. 1999;8(3):201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Jessner U. A DST model of multilingualism and the role of metalinguistic awareness. The Modern Language Journal. 2008;92(2):270–283. [Google Scholar]

- Ju M, Luce P. Falling on sensitive ears: Constraints on bilingual lexical activation. Psychological Science. 2004;15(5):314–318. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushanskaya M, Marian V. The bilingual advantage in novel word learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009a;16(4):705–710. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushanskaya M, Marian V. Bilingualism reduces native-language interference during novel-word learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2009b;35(3):829–835. doi: 10.1037/a0015275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G, Zedeck S. Data analysis for research designs: Analysis-of-variance and multiple regression/correlation approaches. New York: W. H. Freeman; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz MH, Astaneh H. The impact of bilinguality on the learning of English vocabulary as a foreign language (L3) International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2004;7(4):295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Klein E. Second versus third language acquisition: Is there a difference? Language Learning. 1995;45(3):419–465. [Google Scholar]

- Luce PA, Pisoni DB. Recognizing spoken words: The neighborhood activation model. Ear & Hearing. 1998;19(1):1–36. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B. A unified model of language acquisition. In: Ellis NC, Robinson P, editors. Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson JS, Tanenhaus MK, Aslin RN, Dahan D. The time course of spoken word learning and recognition: Studies with artificial lexicons. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132(2):202–227. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian V, Spivey M. Competing activation in bilingual language processing: Within- and between-language competition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2003;6(2):97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Marian V, Blumenfeld HK, Kaushanskaya M. The language experience and proficiency questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:940–967. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/067). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian V, Spivey MJ, Hirsch J. Shared and separate systems in bilingual language processing: Converging evidence from eyetracking and brain imaging. Brain and Language. 2003;86(1):70–82. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00535-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuter R, Allport A. Bilingual language switching in naming: Asymmetrical costs of language selection. Journal of Memory and Language. 1999;40(1):25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S. Second language transfer during third language acquisition. Working Papers in TESOL & Applied Linguistics. 2003;3(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Papagno C, Vallar G. Verbal short-term memory and vocabulary learning in polyglots. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1995;48A(1):98–107. doi: 10.1080/14640749508401378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rast R. The role of linguistic input in the first hours of adult language learning. Language Learning. 2010;60(s2):64–84. [Google Scholar]

- Safont Jorda MP. Metapragmatic awareness and pragmatic production of third language learners of English: A focus on request acts realizations. International Journal of Bilingualism. 2003;7(1):43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz C. Bilingual education enhances third language acquisition: Evidence from Catalonia. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2000;21(1):23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AI, Kroll JF. Bilingual lexical activation in sentence context. Journal of Memory and Language. 2006;55(2):197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián-Gallés N, Marti MA, Cuetos F, Carreiras M. LEXESP: Base de datos informatizada de la lengua española (LEXESP: Computerized database of Spanish language) Departmento de Psicologia Basica, Universitat de Barcelona; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Rosenbaum D. Reaching while calculating: Scheduling of cognitive and perceptual-motor processes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2002;131(2):206–219. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.131.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Joo-hyun, Nakayama K. Target selection in visual search as revealed by movement trajectories. Vision Research. 2008;48(7):853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivey MJ, Marian V. Cross talk between native and second languages: Partial activation of an irrelevant lexicon. Psychological Science. 1999;10(3):281–284. [Google Scholar]

- Spivey MJ, Grosjean M, Knoblich G. Continuous attraction toward phonological competitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(29):10393–10398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503903102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenhaus MK, Magnuson JS, Dahan D, Chambers CG. Eye movements and lexical access in spoken-language comprehension: Evaluating a linking hypothesis between fixations and linguistic processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2000;29(6):557–580. doi: 10.1023/a:1026464108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. Metalinguistic awareness in second and third language learning. Advances in Psychology. 1992;83:531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Viviani P. Eye movements in visual search: Cognitive, perceptual and motor control aspects. Reviews of Oculomotor Research. 1990;4:353–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voga M, Grainger J. Cognate status and cross-script translation priming. Memory & Cognition. 2007;35(5):938–952. doi: 10.3758/bf03193467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hell JG, Mahn AC. Keyword mnemonics versus rote rehearsal: Learning concrete and abstract foreign words by experienced and inexperienced learners. Language Learning. 1997;47(3):507–546. [Google Scholar]

- van Heuven WJ, Dijkstra T, Grainger J. Orthographic neighborhood effects in bilingual word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language. 1998;39(3):458–483. [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Cutler A. Lexical competition in non-native spoken-word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language. 2004;50(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]