Abstract

This prospective study examined the pathways by which religious involvement affected the post-disaster psychological functioning of women who survived Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The participants were 386 low-income, predominantly Black, single mothers. The women were enrolled in the study before the hurricane, providing a rare opportunity to document changes in mental health from before to after the storm, and to assess the protective role of religious involvement over time. Results of structural equation modeling indicated that, controlling for level of exposure to the hurricanes, pre-disaster physical health, age, and number of children, pre-disaster religiousness predicted higher levels of post-disaster (1) social resources and (2) optimism and sense of purpose. The latter, but not the former, was associated with better post-disaster psychological outcome. Mediation analysis confirmed the mediating role of optimism and sense of purpose.

Keywords: Religiousness, Hurricane Katrina, Psychosocial resources

Introduction

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita devastated the Gulf Coast region of the United States, contributing to the loss of nearly 2,000 lives and displacing approximately 1.5 million residents. Recent studies document exceptionally high levels of exposure to traumatic events and psychological distress among survivors (e.g., Galea et al. 2007; Galea et al. 2008; Kessler et al. 2006; Rateau 2009; Rhodes et al. 2010; Sastry and VanLandingham 2009; Wang et al. 2007; Weems et al. 2007; Weisler et al. 2006). The hurricanes were particularly stressful to the low-income and Black residents of New Orleans (Elliott and Pais 2006; Jones-DeWeever 2008; Rhodes et al. 2010), many of whom were left homeless and isolated from their social and community networks.1

Noteworthy, however, is the considerable variation in adaptive coping among survivors of natural disasters. Indeed, declines in functioning following natural disasters are neither consistent nor inevitable (Norris et al. 2002a; b), and researchers have identified a range of factors that may offset the risk (Brewin et al. 2000). Better mental health functioning prior to the storm and supportive social networks are among the most robust protective factors (Brewin et al. 2000; Norris et al. 2002a; Vernberg et al. 1996). In addition, religion and spirituality have long been recognized as an important resource Black communities (Taylor 1988; Taylor et al. 1999) and appear to be particularly salient in the face of traumatic events (Lawson and Thomas 2007). The purpose of the current study was to examine the protective influence of religiousness among hurricane survivors.

Background

The detrimental effects of large-scale disasters on survivors’ psychological well-being have been documented extensively (e.g., Norris et al. 2002a; b; Rubonis and Bickman 1991; Sundin and Horowitz 2003). Studies of the impacts of hurricanes have revealed that as many as half of survivors suffer from some form of disaster-related mental illness (David et al. 1996; Norris et al. 1999; Kessler et al. 2006; Weems et al. 2007; Weisler et al. 2006). Researchers have estimated a prevalence of 30% for PTSD and rates ranging from 31 to 49% for mood disorders among survivors of Hurricane Katrina (Galea et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2007).

Within this context, low-income Black women are at particularly high risk for adverse consequences, including post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression (Brewin et al. 2000; Norris et al. 2005; Solomon and Green 1992; Solomon et al. 1987; Steinglass and Gerrity 1990). Indeed, compared to their male counterparts, Black female survivors of Hurricane Katrina have reported more PTSD and mental health symptoms (Chen et al. 2007). The communities of low-income, Black survivors were hit hard by Katrina, and residents were less likely to have an evacuation plan in place or to evacuate (Spence et al. 2007; Elliott and Pais 2006), increasing their risk of exposure to the storm. Not surprisingly, Black survivors reported greater levels of stress, anger, and depression than White survivors of Katrina (Elliott and Pais 2006; White et al. 2007). Additional factors, including degree of exposure, pre-disaster mental health functioning and younger age (e.g., Brewin et al. 2000) can also exacerbate the risk for post-disaster psychopathology. Likewise, the presence of children is associated with exposure and negative responses to natural disasters, especially among mothers (Bromet et al. 1982; Gibbs 1989; Morrow 1997).

Even among the most vulnerable populations, however, there is considerable variability in post-disaster functioning (Ferraro 2003. Researchers have identified a range of protective factors associated with better psychological well-being following disasters, including active coping, internal locus of control, low perception of threat, and high socioeconomic status (Gibbs 1989. Likewise, personal faith and involvement in spiritual and religious communities are thought to be vital protective resources. Religious involvement is thought to provide survivors with a sense of hope and meaning as well as access to social support networks (Lim and Putnam 2010; Smith et al. 2000; Weaver et al. 1996). These protective factors, in turn, can enhance survivors’ overall happiness (Lim and Putnam 2010) and resilience in the face of major life stressors (e.g., Pargament et al. 2005) and contribute to healing (Maton and Wells 1995). Indeed, this may be particularly true for Black Americans, for whom the mental health benefits of religious practice, affiliation, and belief have been widely documented (Chatters et al. 1999; Taylor et al. 1999; Levin et al. 1995). In one study, for example, Black Americans were more than twice as likely as White Americans to report relying on religious faith to cope within the after-math of Katrina (Elliott and Pais 2006). It is hence important to consider the processes through which religion might serve as a protective factor among Black survivors of Hurricane Katrina.

Religiousness and Psychological Distress

Many studies have provided evidence of a positive relationship between religiousness/spirituality and well-being (e.g., George et al. 2002; Koenig et al. 2001; Miller and Thoresen 2003). Religious attendance and involvement are strongly related to physical health (e.g., Koenig et al. 1997), mental health (e.g., Ellison 1995; Smith et al. 2003), longevity (e.g., Hummer et al. 1999; Koenig et al. 1999; Strawbridge et al. 1997), and post-traumatic growth (Koenig et al. 2001; Milam et al. 2004; Tedeschi and Calhoun 1996). Moreover,Smith et al. (2000) found that religious factors—measured retrospectively—were strong predictors of the well-being of the survivors of the 1993 Midwest flood.

Religious involvement appears to promote well-being through both external (or social) processes, such as providing opportunities for social engagement and volunteerism, and internal (or personal) processes, such as inspiring a sense of purpose and optimism (Koenig 2001); Koenig et al. 2001). Relative to non-religious individuals, religious people tend to be more socially active and have higher levels of perceived social support (Krause 2002); Krause et al. 2001; Lim and Putnam 2010; Oman and Reed 1998). Perceived social support, in turn, appears to partially mediate the effects of religious involvement on measures of both physical (Myer 2000; Powell et al. 2003) and psychological well-being (Ai et al. 2007; Lim and Putnam 2010; Salsman et al. 2005). In addition, researchers have suggested a link between social support and better adjustment after major life events (Ai et al. 2007; Brummett et al. 1998; Pirraglia et al. 1999) and natural disasters (Benight et al. 1999; Brewin et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2000), including Hurricane Katrina (Chen et al. 2007; Lowe et al. 2010). A Gallup poll (2005) conducted shortly after Hurricane Katrina indicated that many survivors saw their religious faith and church-based social networks as important sources of emotional support.

Social support may be an especially salient component of the religious experience of Black Americans. In one study, for example, social support mediated the association between religious involvement and physical health for Black Americans, but not for White Americans (Ferraro and Koch 1994). Black churches can provide a rich source of social support, both through organized church-based volunteer efforts and informal acts of charity and kindness among congregates. This in turn could lead to a higher sense of social efficacy, that is, the extent to which an individuals see themselves as capable of relating to and providing support to others (e.g., Patrick et al. 2007).

In addition to these social processes, psychological processes are also thought to mediate the relationship between religion and better outcomes. Indeed, religion can provide a range of psychological benefits (Koenig et al. 2001; Park and Folkman 1997), which can be particularly salient in the face of stressful and catastrophic events (Ai et al. 2003; Pargament 1997). Religiousness is significantly and positively related to optimism (Idler and Kasl 1995; Salsman et al. 2005; Sethi and Seligman 1993), particularly among people encountering significant life stress (Koenig et al. 2001; Ai et al. 2003). Optimism, a cornerstone of religious teaching and beliefs, is conceptualized as global, stable, and positive faith, or expectations that good things will be plentiful in the future while bad things will be scarce (Scheier and Carver 1985, 1993). Optimism, in turn, is related to better physical health (Peterson et al. 1988), longevity (e.g., Seligman 1991), as well as better mental health (e.g., Giltay et al. 2006; Puskar et al. 1999) in vulnerable populations, including individuals with chronic diseases (for a review, see Andersson 1996) and people exposed to the September 11 terrorist attacks (Ai et al. 2006). Optimism has also been associated with post-traumatic growth, that is, improvements relative to baseline functioning following traumatic events (e.g., Davis et al. 1998; Evers et al. 2001). Researchers have found that individuals who rate higher in optimism tend to engage in adaptive problem-focused coping and constructive thinking and have greater acceptance of uncontrollable situations than those who are less optimistic (Aspinwall et al. 2001; Aspinwall and Taylor 1992). As with social support, optimism has been found to mediate the association between religiousness and well-being (Salsman et al. 2005).

Similarly, there is a growing body of research to support the centuries-old notion that religion provides people with a sense of meaning and purpose in life (Dufton and Perlman 1986; French and Joseph 1999; George et al. 2002; Park 2005). Researchers have documented that a sense of meaning and purpose in life are positively associated with psychological well-being (e.g., Hill et al. 2010; Krause 2003), suggesting a potential meditating role (George et al. 2002; Vilchinsky and Kravetz 2005). For example,Nelson et al. (2009) found that a sense of inner peace and meaning mediated the inverse relationship between religiousness and depression among men with prostate cancer. Results from a recent exploratory qualitative study on African American survivors of Hurricane Katrina suggest that seeking meaning and purpose through religiousness and spirituality is a salient coping response among this population (Salloum and Lewis 2010).

Present Study

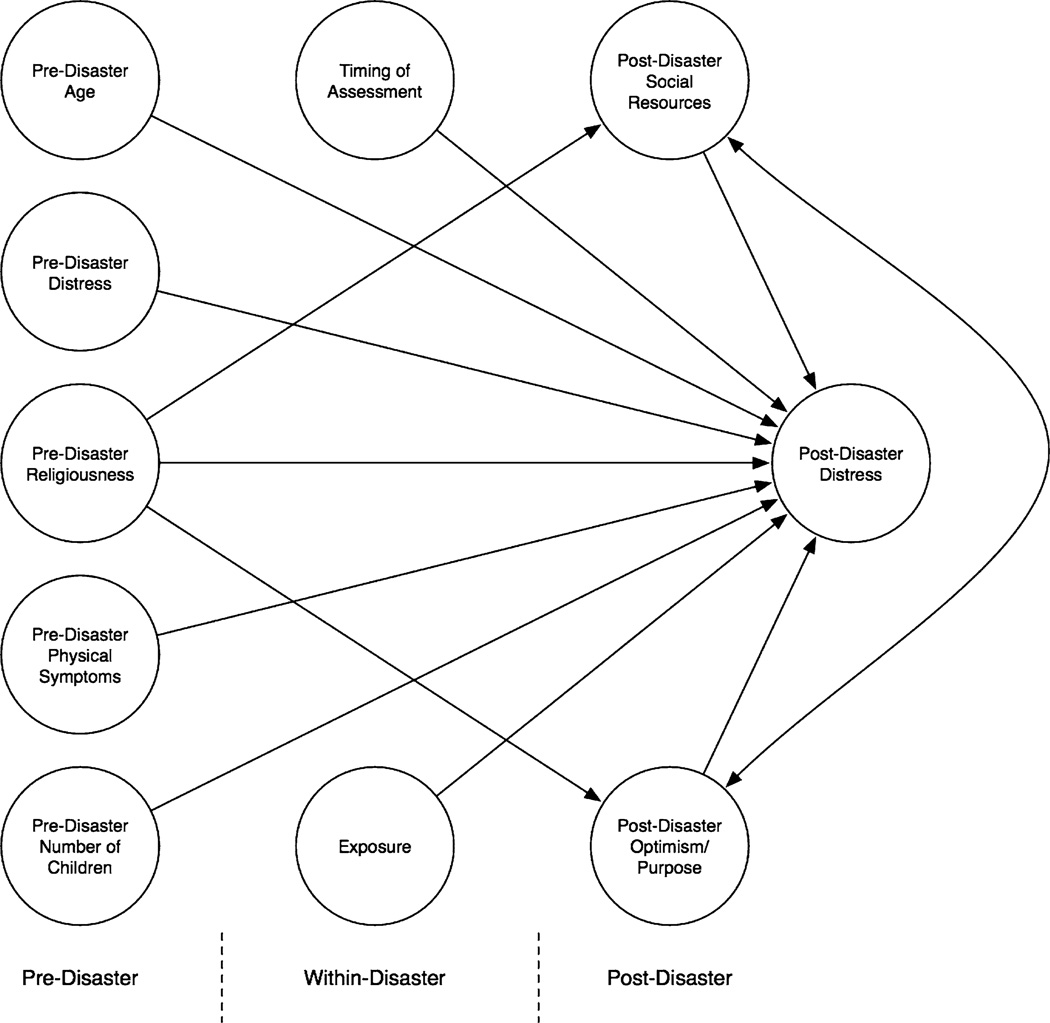

Taken together, the literature suggests that religion might serve as a protective resource against the negative psychological effects of natural disasters through its positive influence on survivors’ (1) social relations, including perceived social support and social efficacy, and (2) psychological functioning, including sense of optimism and purpose in life. These two pathways were explored in the context of a longitudinal study, which included both pre- and post-Hurricane Katrina data.2 The vast majority of studies of disaster outcomes lack pre-disaster data (Norris and Elrod 2006). Pre-disaster data allow researchers to better clarify the temporal order of the event and outcome variables, as well as to control for pre-existing levels of psychological health. In the current study, we hypothesized that, after controlling for pre-disaster levels of distress and levels of exposure to the disaster, religiousness would be associated with protective interpersonal and intrapersonal factors, which in turn would be associated with post-disaster distress (Fig. 1). In particular, we predicted that higher levels of pre-disaster religiousness would be associated with better post-disaster psychological outcomes via (1) post-disaster social resources and (2) post-disaster optimism and sense of purpose.

Fig. 1.

The hypothesized model predicting post-disaster distress

Method

Sample and Procedure

The sample consisted of residents in the greater New Orleans region who survived Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. This study includes three waves of data. The baseline (T0) data were collected from 1,019 students in two community colleges in New Orleans. These students were enrolled in Opening Doors, an education intervention program (Brock and Richburg-Hayes 2006). The participants provided information on socio-demographic characteristics, family background, and education history. Participants also reported their physical and mental health, including, but not limited to, health conditions that limit activities, height and weight, tobacco use, symptoms of stress, and psychological distress.

The Pre-Katrina survey (T1) was administered to respondents a year after T0 in the months preceding Hurricane Katrina. The collection of data was interrupted by Hurricane Katrina, by which point 492 of the 1,019 original respondents had completed the survey. The survey included a range of background demographic questions as well as specific questions about religiousness, physical health (e.g., difficulties with activities of daily living and obesity), and mental health (e.g., psychological distress, stress, substance use, and risky sexual behaviors). The survey also contained measures of optimism, social support and social efficacy. Within a year after Hurricane Katrina, telephone follow-ups with those who completed the pre-Katrina survey (T1) were conducted by trained interviewers. Four hundred and two (81.7%) of the 492 respondents who participated in T1 were successfully contacted and completed the post-Katrina survey (T2). Data collection for T2 began in May 2006, 9 months after the Hurricane, and ended in March 2007. In addition to the questions in T1, the T2 survey included a detailed set of questions about experiences during and after the hurricane (e.g., the timing of evacuation, traumatic experiences during and shortly after the hurricane, property damage, and sources of formal and informal support).

The final sample consisted of 386 women who completed interviews at all three time points. At baseline, most participants were unmarried and had one or two children. Many participants were financially disadvantaged: approximately 70% received some type of government assistance (e.g., food stamps) at the time they enrolled in the study (T0). At the time of enrollment, the average monthly income of the participants was low (M = $1,617; SD = $1,092). To determine whether those who completed the post-disaster interview differed from those who did not, t tests were conducted on all variables assessed before Hurricane Katrina (i.e., T1). Results indicated no differences between the two groups on any of the variables included in this study. Table 1 shows the demographic information of the participants included in the current analyses.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of participants at time 1 (pre-disaster)

| Characteristic | Present study (N = 386) |

|---|---|

| Female | 100% |

| Average age (years at baseline) | 25.4 (SD = 4.43) |

| Living with neither spouse nor partner | 72.8% |

| Hispanic | 2.8% |

| Black non-Hispanic | 82.1% |

| White non-Hispanic | 9.8% |

| Number of children | |

| One | 42.5% |

| Two | 32.1% |

| Three or more | 25.4% |

| Households receiving any social benefits (UI, SSI, food stamps, or TANF) | 72.0% (at baseline) |

Measures

A series of surveys containing questions concerning health and social resources were administered in both waves of the study.

Psychological Distress

Two indicators were used to measure pre-disaster distress: the K6 scale (Kessler et al. 2002) and the abbreviated Perceived Stress Scale (PSS4; Cohen and Williamson 1988). The K6 scale is a six-item measure of nonspecific psychological distress and has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Furukawa et al. 2003). It includes items such as “During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up?” Respondents answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (all the time) to 5 (none of the time). A previous validation study (Kessler et al. 2003) suggests that a score of 0 to 7 can be considered as probable absence of mental illness, a score of 8 to 12 can be considered as probable mild or moderate mental illness, and a score of 13 or greater can be considered as probably serious mental illness. Cronbach’s alpha of the K6 scale in this study was .76 for T1 and .82 for T2.

The PSS4 is a four-item stress measure that assesses whether the individual feels overwhelmed by current life events in the past month. It has been widely used in studies of the effects of stress on health outcomes. An example of the items is “In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?” Participants answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Cronbach’s alpha was .74 for T1 and .82 for T2.

Religiousness

This was measured with two single-item questions inquiring about the frequency of attending religious services and the importance of religion to the participant. Report of religious attendance was based on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (several times per week). Religious importance was measured with an item asking participants to rate the level of importance of religion in their lives using a 5-point scale. Responses ranged from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (very important). Because the scales of the two items are different, the average of their proportion of maximum scores was used in the analysis. Only T1 religiousness was included in the current analysis.

Social Resources

This was assessed with an abbreviated form of the Social Provisions Scale (SPS; Cutrona and Russell 1987) and the Social Efficacy Scale (SES; Brock and Richburg-Hayes 2006). Eight items from the SPS, a widely used measure of perceived social support, were administered, including questions asking whether participants have people in their lives who value them and on whom they can count. Response options were given in a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was .82 for T2. The SES was developed by the MacArthur Network on Transitions to Adulthood for the evaluation of the Opening Doors program (Brock and Richburg-Hayes 2006). It contains five items (e.g., “You feel that you are important, that you ‘matter,’ to other people,” “People often seek your advice and support”). Response options were given in a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). In this analysis, only T2 social support was included and the Cronbach’s alpha was .72.

Optimism and Sense of Purpose

The Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) is a self-report measure of optimism that consists of six items (Scheier et al. 1994). Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Three of the six items were framed positively (e.g., “I am always optimistic about my future”), and the remaining three were framed negatively (e.g., “If something can go wrong for me, it will”). In this study, only optimism at T2 was used and the Cronbach’s alpha was .70.

The Life Engagement Test (LET) is a six-item self-report measure of purpose in life (Scheier et al. 2006). Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Three of the six items were framed positively (e.g., “I have lots of reasons for living”), and the remaining three were framed negatively (e.g., “There is not enough purpose in my life”). In this study, only optimism at T2 was used and the Cronbach’s alpha was .85.

Physical Symptoms

Participants were asked to indicate if they have had any of a range of physical symptoms over the year before T1: (1) an episode of asthma or an asthma attack, (2) trouble with one’s back, (3) trouble with digestion, such as stomach ulcers, frequent indigestion or stomach upset, (4) trouble with frequent headaches or migraines, and (5) diagnosed with or treated for anemia. For all questions, responses were coded as “Yes” = 1, and “No” = 0. Positive responses to these items were summed for the analysis.

Hurricane Exposure

This was measured with a scale designed by the Washington Post, the Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Harvard School of Public Health (Brodie et al. 2006). Participants were asked in the T2 survey to indicate if they experienced any of the following as a result of the hurricanes: (1) no fresh water to drink, (2) no food to eat, (3) felt their life was in danger, (4) lacked necessary medicine, (5) lacked necessary medical care, (6) had a family member who lacked necessary medical care, (7) lacked knowledge of safety of their children, (8) lacked knowledge of safety of their other families members, and (9) whether there was any death among family and friends. Participants were asked these questions for both Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. In addition, participants were asked whether they had lost a house, a vehicle (e.g., car, motorcycle), and whether a family pet had died or been lost due to the hurricanes and their aftermath. For all questions, responses were dichotomous (“Yes” = 1 and “No” = 0). A composite score (possible range = 0 to 20) was created with the count of affirmative responses to these items.

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic questions were collected at all three time points. In this study, participants’ reported age and race at T0 and number of children at T1 were included in the analyses (see Table 1).

Timing of T2 Assessment

Data collection for T2 began in May 2006 and ended in March 2007. The number of months between Hurricane Katrina the T2 assessment was included in the analyses.

Data Analysis

First, the normality of the data was examined to determine whether the assumptions of multivariate statistical estimations used in the study were met. All measured continuous variables were examined for departure from normality in terms of skewness and kurtosis. Items of each scale with continuous variables (i.e., pre-disaster psychological distress, post-disaster psychological distress, social resources, and optimism/sense of purpose) were then arranged into parcels, resulting in three partials per variable (Little et al. 2002). Parcel arrangements (i.e., which items to put together) were based on each item’s factorial loading on their latent construct, and then the average of the items on each parcel was taken. Second, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to evaluate the adequacy of the measurement model and the structural model (Fig. 1). Latent constructs were created for each variable, including the single-item variables. The construct of “social resources” was created with the three parcels from perceived social support and social efficacy. The construct of “optimism/sense of purpose” was created with the three parcels from optimism and purpose in life. One-item latent variables were created for each of the other variables (i.e., age, number of children, religiousness, timing of T2 assessment, exposure, and physical symptoms). Third, bootstrapping was used to test the significance of mediated effects in the model.

Results

Missing Data Analysis

Although not missing completely at random (Little’s MCAR test: χ2 [1112] = 1,399.91, p < .001), the overall missingness was .3%. None of the variables had more than 1.6% of missing values. Due to the low missing rate, missing data were handled with single imputation.

Descriptive Results

A large majority of the participants were religious. Only 2.0% rated religion as not at all important or not too important, while most participants (76.2%) reported that religion was very important in their lives. Similarly, most (72.1%) reported attending religious services at least once to twice per month. The average of the proportion of maximum scores of the two variables was used in the current analyses.

As expected, psychological distress increased from pre-disaster to post-disaster. The average on the K6 scale increased from 5.56 to 6.69, t(385) = 4.19, p < .001. The results of the K6 scale indicated that the fraction of the sample with probable mild or moderate mental illness rose from 16.3 to 23.6%, whereas the fraction with probable serious mental illness increased from 6.5 to 14.0%. The post-disaster prevalence rates are comparable to those reported by other researchers studying the mental health of survivors of Hurricane Katrina (e.g., Galea et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2007). No violation of normal distribution was found in the variable included in the hypothetical model. The means, standard deviations, and correlations of the measured variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, zero-order correlations, [and 95% confidence intervals] of measured variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Disaster | |||||||||||||||

| 1. Age | – | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Number of Children | .33*** | – | |||||||||||||

| [.24, .42] | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Physical Symptoms | .10† | .06 | – | ||||||||||||

| [.00, .20] | [−.04, .16] | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Importance of Religion | 0.09 | .01 | −.05 | – | |||||||||||

| [−.01, .19] | [−.09, .11] | [−.15, .05] | |||||||||||||

| 5. Frequency of Church attendance | .09† | −.02 | −.05 | .47*** | – | ||||||||||

| [−.01, .19] | [−.12, .08] | [−.15, .05] | [.39, .55] | ||||||||||||

| 6. K6 | 0.04 | .06 | .38*** | −.09† | −.12* | – | |||||||||

| [−.06, .14] | [−.04, .16] | [.29, .46] | [−.19, .01] | [−.22, −.02] | |||||||||||

| 7. PSS4 | 0 | −.07 | 26*** | −.13* | −.16** | .62*** | – | ||||||||

| [−.10, .10] | [−.17, .03] | [.16, .35] | [−.23, −.03] | [−.26, −.06] | [.56, .68] | ||||||||||

| Post-disaster | |||||||||||||||

| 8. Timing of T2 assessment | −.02 | −.09 | −.05 | .02 | −.02 | .12* | .18** | – | |||||||

| [−.11, .08] | [−.19, .01] | [−.14, .05] | [−.08, .12] | [−.12, .08] | [.02, .22] | [.08. .28] | |||||||||

| 9. Exposure to disaster | .20*** | .17** | .16** | .12* | .06 | .15** | .05 | −.10 | – | ||||||

| [.10, .29] | [.07, .27] | [.06, .26] | [.02, .22] | [−.04, .06] | [.05, .25] | [−.05, .15] | [−.20, .00] | ||||||||

| 10. SPS | −.07 | −.16** | .00 | .03 | .08 | −.08 | −.17** | −.05 | −.17** | – | |||||

| [−.17, .03] | [−.26, −.06] | [−.10, .10] | [−.07, .13] | [−.02, .18] | [−.18, .02] | [−.28, −.08] | [−.15, .05] | [−.28, −.08] | |||||||

| 11. SES | −.02 | −.08 | −.04 | .09† | .13* | .03 | −.14** | −.06 | −.06 | .50*** | – | ||||

| [−.12, .08] | [−.18, .02] | [−.14, .06] | [−.01, .19] | [.03, .23] | [−.07, .13] | [−.25, −.04] | [−.16, .04] | [−.16, .04] | [.43, .58] | ||||||

| 12. LOT-R | −.01 | .13* | −.05 | .13* | .20*** | −.15** | −.27*** | −.12* | −.03 | .31*** | .43*** | – | |||

| [−.13, .07] | [.03, .23] | [−.15, .05] | [.03, .23] | [.10, .29] | [−.25, −.05] | [−.37, −.18] | [−.22, −.02] | [−.13, .07] | [.22, .40] | [.35, .51] | |||||

| 13. LET | −.02 | .06 | .00 | .18*** | .14** | −.08 | −.21*** | −.10* | −.02 | .40*** | .45*** | .66*** | – | ||

| [−.12, .08] | [−.04, .16] | [−.10, .10] | [.08, .28] | [.04, .24] | [−.18, .02] | [−.31, −.12] | [−.20, −.00] | [−.12, .08] | [.32, .49] | [.38, .53] | [.60, .72] | ||||

| 14. K6 | .09 | −.01 | .22*** | .02 | −.05 | .36*** | .33*** | .03 | .29*** | −.28*** | −.15** | −.31*** | −.29*** | – | |

| [−.01, .19] | [−.11, .09] | [.13, .32] | [−.09, .12] | [−.15, .05] | [.28, .45] | [.25, .43] | [−.07, .13] | [.20, .38] | [−.38, −.19] | [−.25, −.05] | [−.40, −.22] | [−.38, −.20] | |||

| 15. PSS4 | .10† | −.06 | .17** | −.07 | −.12* | .27*** | .37*** | .03 | .20*** | −.31*** | −.19*** | −.39*** | −.29*** | .69*** | – |

| [.00, .20] | [−.16, .04] | [.07, .27] | [−.17, .03] | [−.22, −.02] | [.18, .37] | [.29, .46] | [−.07, .13] | [.11, .31] | [−.40, −.22] | [−.29, −.09] | [−.48, −.31] | [−.38, −.20] | [.64, .75] | ||

| Mean | 25.42 | 1.95 | 1.46 | 3.61 | 2.33 | 5.56 | 4.28 | 11.94 | 4.09 | 17.52 | 17.26 | 12.44 | 14.86 | 6.69 | 5.35 |

| [24.98, 25.87] | [1.84, 2.05] | [1.33, 1.60] | [3.53, 3.69] | [2.20, 2.45] | [5.15, 5.96] | [3.95, 4.61] | [11.69, 12.19] | [3.74, 4.42] | [17.13, 17.90] | [16.94, 17.57] | [12.12, 12.76] | [14.56, 15.15] | [6.16, 7.21] | [4.99, 5.71] | |

| SD | 4.43 | 1.06 | 1.35 | 0.8 | 1.25 | 4.06 | 3.3 | 2.46 | 3.49 | 3.84 | 3.13 | 3.18 | 2.97 | 5.21 | 3.6 |

p <. 10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Measurement Model

Prior to testing the hypothesized model, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine the fit of the measurement model. In this study, the measurement model was estimated using the maximum-likelihood method in Mplus 6.0. Model fit statistics suggested good fit, χ2 (df = 93, N = 386) = 143.92, p < .001, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .038 (90% confidence interval [CI]: .025, .049). Correlations among the latent variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlations of latent variables in the measurement model

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-disaster age | – | |||||||||

| 2 | Pre-disaster number of children | .33*** | – | ||||||||

| 3 | Pre-disaster physical symptoms | .10 | .07 | – | |||||||

| 4 | Pre-disaster religiousness | .10 | .01 | −.07 | – | ||||||

| 5 | Pre-disaster psychological distress | .03 | −.01 | .39*** | −.18** | – | |||||

| 6 | Timing of T2 assessment | −.02 | −.09 | −.05 | −.00 | .18** | – | ||||

| 7 | Exposure to disaster | .20*** | .17** | .15** | .09 | .12** | −.10 | – | |||

| 8 | Post-disaster social resources | −.07 | −.16** | −.02 | .12* | −.15** | −.07 | −.14** | – | ||

| 9 | Post-disaster optimism/sense of purpose | −.03 | .11* | −.04 | .24*** | −.27*** | −.15** | .01 | .60*** | – | |

| 10 | Post-disaster psychological distress | .11* | −.04 | .23*** | −.09 | 46*** | .03 | .29*** | −.33*** | −.44*** | – |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Structural Model Fit

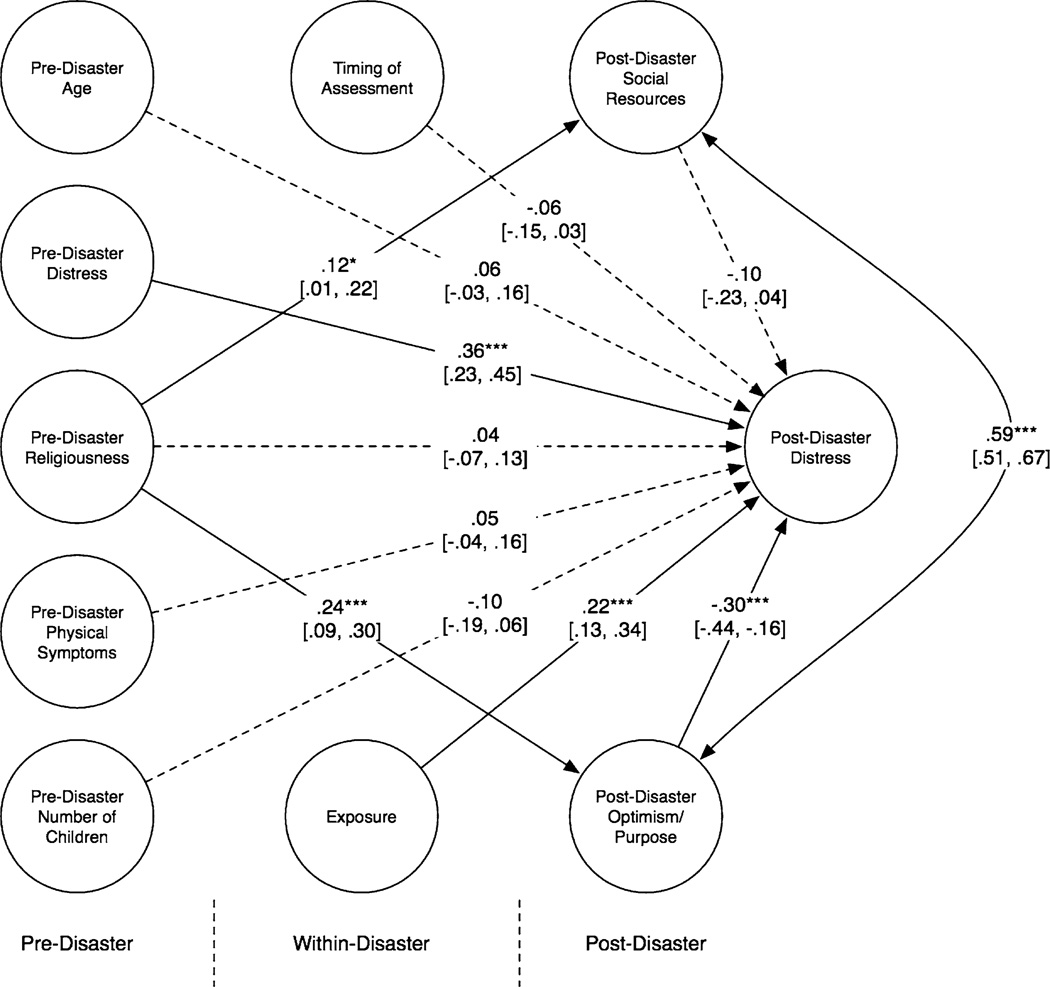

We hypothesized that, controlling for age, number of children, pre-disaster psychological distress, physical health, timing of assessment, and level of exposure to the disasters, pre-disaster religiousness would be associated with post-disaster psychological distress via two mediators: post-disaster social resources and post-disaster optimism/ sense of purpose (Fig. 1). The estimation of the hypothesized model with Mplus resulted in a good fit to the data, χ2 (df = 105, N = 386) = 198.34, p<.001, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .048 (90% CI: .038, .058). The model accounted for 35.7% of the variance in post-disaster distress.

Major Pathways to Post-disaster Distress

Standardized coefficients of each pathway are shown in Fig. 2. The significant paths were partially consistent with the hypothesized model. While no direct effect of religiousness on post-disaster distress was found, significant pathways from pre-disaster religiousness to post-disaster social resources and optimism/sense of purpose were indicated. Results also showed that post-disaster distress was predicted by lower levels of optimism/sense of purpose, after controlling for pre-disaster psychological distress, the time lapse between Hurricane Katrina and post-disaster assessment, level of exposure, age, number of children, and pre-disaster physical health.

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model predicting post-disaster distress. Estimates are all standardized. Numbers in brackets represent 95% confidence intervals. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Indirect Effects

In order to test the magnitude and significance of mediation effects in predicting post-disaster distress in the hypothesized model (Fig. 1), a bootstrap procedure was used. Bootstrapping was conducted with Mplus, following the guidelines offered by Shrout and Bolger (2002). First, 1,000 bootstrap samples were formed using existing data-set. Second, the path coefficients of the final model (Fig. 2) were estimated 1,000 times. Third, the estimates of each path coefficient were used to calculate mean and standard error of the indirect effects across the 1,000 bootstrap samples. According to Shrout and Bolger (2002), if the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean indirect effect does not include zero, the indirect effect is considered statistically significant at the .05 level. The results indicated that optimism/sense of purpose, but not social resources, mediated the relationship between religiousness and post-disaster psychological distress ( = −.07, p < .05; 95% CI: −.13, −.02).

Discussion

The present prospective study provides important evidence about how religious involvement may influence the psychological functioning of low-income, female survivors of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Although a direct effect between pre-disaster religiousness and post-disaster psychological distress was not found, pre-disaster religiousness was predictive of better post-disaster psychosocial functioning, including more social resources and a stronger sense of optimism and purpose. The latter, in turn, was associated with lower levels of psychological distress after the storm. The results also indicated that this was a mediation effect.

Several findings in the present study are consistent with previous work (Norris et al. 2002b). First, post-disaster distress was predicted by severity of exposure to the hurricanes. Those who suffered greater exposure to the disaster and related stressors reported more psychological symptoms. Also consistent with past findings (Norris et al. 2002b), pre-disaster distress was a strong predictor of post-disaster distress. Those who were psychologically distressed prior to the hurricane tended to get worse after the hurricane. Psychologically distressed individuals may have been more affected by the disaster than those who were relatively less distressed. Indeed, although not a focus of the current study, our results indicate that pre-disaster psychological distress was positively correlated with level of exposure, suggesting that those who were more distressed prior to the storm either experienced a greater number of stressful events during and after the Katrina or they perceived more stressful events. In addition, pre-disaster psychological distress was negatively correlated with social resources and optimism/sense of purpose. Hence pre-disaster distress might have negatively affected both participants’ perceptions of the hurricanes as well as their capacity to mobilize support in ways that might have minimized actual severity of exposure. Objective indicators, such as flood depth, and additional subjective ratings, would have helped strengthen the assessment of exposure.

The hypothesis that pre-disaster religiousness would be associated with lower levels of post-disaster psychological distress was partially confirmed. Contrary to predictions, pre-disaster religiousness did not directly predict post-disaster distress. This lack of a direct association is consistent withAi et al. (2007), who reported only indirect effects of religiousness on psychological functioning, via coping style and psychosocial resources, among surgery patients. In our study, higher pre-disaster religiousness was, however, a significant predictor of post-disaster social resources and optimism/sense of purpose. These findings converge with those of previous studies on the psychological and social pathways of the benefits of religiousness (e.g., Koenig 2001).

Although a significant negative correlation between social support and post-disaster psychological distress was found at both the scale-level (Table 2) and the latent-level (Table 3), a negative association between social resources and psychological distress did not emerge in our SEM model. It could hence be speculated that, after controlling for internal psychosocial resources (e.g., optimism/sense of purpose), the contribution of social resources may have been attenuated. Some past studies have failed to model different psychosocial resources simultaneously (e.g., Salsman et al. 2005), rendering potentially biased estimations. Like the current one, future studies of social resources and psychological distress should consider including other psychosocial factors and testing them in the same model, controlling for their associations.

Another possibility is that in the context of large-scale faith community upheaval and dispersion, social support was a less salient predictor than internal resources. In the current student, we found a negative correlation between levels of hurricane exposure and post-disaster perceived social support (Table 2), which concurs with previous observations of post-disaster social support deterioration (Kaniasty and Norris 2004, 2009). Furthermore, using the same sample as the current study, Lowe, Chan, and Rhodes (2010) found support for the deterioration model, especially the impact of social support deterioration on mental health. Nonetheless, other psychosocial resources were not included in their model. Additional studies are needed to further substantiate social support deterioration models and to shed light on the potentially interdependent, or even causal, relationships between various psychosocial resources, and their impact on mental health.

Consistent with our predictions, optimism/sense of purpose was negatively associated with post-disaster distress, even after controlling for the timing of assessment, severity of exposure, physical health, and pre-disaster distress. These findings contribute to the existing literature, which consistently demonstrates that internal psychosocial resources negatively predict psychological distress (e.g., Aspinwall and Taylor 1992; Rice et al. 1993) and are protective in stressful situations (e.g., Scheier and Carver 1992), including natural disasters (e.g., Sumer et al. 2005). Our results suggest that, in the face of a devastating event, religiousness provides a sense of optimism and purpose that might have helped the survivors maintain their psychological health. This was further strengthened by the mediation analysis, which indicated that psychological, but not social, resources mediated the relationship between pre-disaster religiousness and post-disaster psychological distress.

Taken together, our findings are in line with past research on resistance and resilience and highlight the process through which religiousness helps maintain psychological well-being in the context of aversive situations (e.g., Bonanno 2004). Religious communities have the potential to serve individuals in areas of need, which are often beyond the reach of government services. They can fill the void in both prevention and intervention efforts, especially among vulnerable populations. Our results underscore the relative importance of internal, or personal, resources in the context of a natural disaster.

A major strength of this study is the inclusion of pre-disaster data. Most disaster studies rely on retrospective data when investigating the factors and pathways through which post-disaster outcomes are affected (see Norris and Elrod 2006). This study controlled for pre-disaster demographic variables as well as psychological distress, which permitted a test of the influence of pre-disaster religiousness on post-disaster psychosocial resources and psychological distress. Furthermore, the resulting structural equation model accounted for a sizable 35.2% of variance in post-disaster distress, indicating its robustness.

In interpreting the results of this study, several limitations should be kept in mind. First, religiousness was measured with two general, single-item questions. Because the population of interest has a relatively high level of religious involvement (e.g., Taylor et al. 1999), the variability of the key indicators of religiousness might have been limited. Furthermore, additional items would have helped to capture the multifaceted and multilevel nature of the construct (e.g., Emmons and Paloutzian 2003; Gorsuch 1984; Hill 2005; Hill and Pargament 2003) and its effects on mental health processes (Levy et al. 2009). Many aspects of religious beliefs and experiences were left unexamined, including denomination, level of commitment, history of religiousness, religious attribution, and religious coping. Particularly relevant to the current context is religious attribution, that is, the extent to which one perceives stressful events as caused by God’s love or God’s anger (Pargament and Hahn 1986; Pargament 1997; Smith et al. 2000). Studies examining the pathways through which such religious factors benefit mental health outcomes should consider including other psychosocial resources as well as attribution style and religious coping variables.

Second, the causal relationship between post-disaster psychosocial resources and post-disaster distress cannot be confidently established. It is just as possible that heightened psychological distress led to lower levels of optimism/ sense of purpose. Similarly, we did not model the causality between psychosocial resources and exposure to hurricane-related events. Although we found significant correlations between social resources and exposure and between optimism/ sense of purpose and exposure, the direction of causality cannot be confidently established.

Third, this study relied on self-report measures, which are susceptible to subjective biases. Particularly problematic is the exposure measure, since it is based on a person’s report of resource loss and perceived threat. It is possible that the self-report of exposure was influenced by the person’s post-disaster mental health, thus confounding the present findings. Compared with objective measures of trauma, however, subjective experiences of events might be even more predictive of psychological functioning (Friedman 2006). Nonetheless, future research should seek to supplement subjective reports with more objective measures of exposure and post-trauma functioning.

Finally, participants in this study are not representative of the entire population affected by the hurricanes, thus reducing the generalizability of the findings. Nonetheless, by highlighting the experience of poor, predominately Black, single mothers—a population that is faced with multiple stressors and of higher risk of adverse outcomes— our findings shed light on to a particularly vulnerable, underserved, and understudied group.

Conclusions

This study highlights the role of religion, especially to those who have religious faith and regularly attend religious events. The findings of this study suggest that religiousness, specifically its perceived importance and the frequency of religious participation, provides important psychological resources, especially optimism and sense of purpose, that could help to promote more favorable post-disaster outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01HD046162, the National Science Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, the Center for Economic Policy Studies at Princeton University, and the National Poverty Center at the University of Michigan. We thank Alice Carter and Sarah Schwartz for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

Footnotes

Acknowledging that different communities have different preferences, in this article we use the terms “African American,” “Black American,” and “Black” interchangeably.

For the sake of brevity, unless otherwise indicated, “Hurricane Katrina” refers to both Hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

Contributor Information

Christian S. Chan, Email: christian.chan@umb.edu, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, MA 02125, USA.

Jean E. Rhodes, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, MA 02125, USA

John E. Pérez, College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

References

- 1.Ai AL, Evans-Campbell T, Santangelo LK, Cascio T. The traumatic impact of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the potential protection of optimism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:689–700. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ai AL, Park CL, Huang B, Rodgers W, Tice TN. Psychosocial mediation of religious coping styles: A study of short-term psychological distress following cardiac surgery. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:867–882. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ai AL, Peterson C, Huang B. The effect of religiousspiritual coping on positive attitudes of adult Muslim refugees from Kosovo and Bosnia. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2003;13:29–47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson G. The benefits of optimism: A meta-analytic review of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences. 1996;21:719–725. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aspinwall LG, Richter L, Hoffman RR, II I. Understanding how optimism works: An examination of optimists’ adaptive moderation of belief and behavior. In: Chang EC, editor. Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. Modeling cognitive adaptation: A longitudinal investigation of the impact of individual differences and coping on college adjustment and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:989–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benight CC, Swift E, Sanger J, Smith A, Zeppelin D. Coping self-efficacy as a mediator of distress following a natural disaster. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1999;12:2443–2464. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewin C, Andrews B, Valentine J. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brock T, Richburg-Hayes L. Paying for persistence: Early results of a Louisiana scholarship program for low-income parents attending community college. New York: MDRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brodie M, Weltzien E, Altman D, Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Experiences of Hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston shelters: Implications for future planning. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1402–1408. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bromet EJ, Parkinson DK, Schulberg HC, Dunn LO, Gondek PC. Mental health of residents near the Three Mile Island reactor: A comparative study of selected groups. Journal of Preventive Psychiatry. 1982;1:225–276. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Barefoot JC, Bosworth HB, Clapp-Channing NE, Siegler IC, et al. Social support and hostility as predictors of depressive symptoms in cardiac patients one month after hospitalization: A prospective study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60:707–713. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199811000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD. African American religion participation: A multi-sample comparison. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999;38:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen AC-C, Keith VM, Airriess C, Li W, Leong KJ. Economic vulnerability, discrimination, and Hurricane Katrina: Health among Black Katrina survivors in eastern New Orleans. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2007;13:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cutrona CE, Russell DW. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Advances in Personal Relationships. 1987;1:37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 18.David D, Mellman TA, Mendoza LM, Kulick-Bell R, Ironson G, Schneiderman N. Psychiatric morbidity following Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:607–612. doi: 10.1007/BF02103669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis CG, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J. Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: Two construals of meaning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:561–574. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dufton B, Perlman D. The association between religiosity and the Purpose-in-Life Test: Does it reflect purpose or satisfaction? Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1986;14:42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott JR, Pais J. Race, class, and Hurricane Katrina: Social differences in human responses to disaster. Social Science Research. 2006;35:295–321. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellison CG. Race, religious involvement, and depressive symptomatology in a southeastern U.S. community. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;40:1561–1572. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00273-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emmons RA, Paloutzian RF. The psychology of religion. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:377–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evers AWM, Kraaimaat FW, van Lankveld W, Jongen PJH, Jacobs JWG, Bijlsma JWJ. Beyond unfavorable thinking: The Illness Cognition Questionnaire for chronic diseases. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1026–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferraro FR. Psychological resilience in older adults following the 1997 flood. Clinical Gerontologist. 2003;26:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferraro KF, Koch JR. Religion and health among Black and White adults: Examining social support and consolation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33:362–375. [Google Scholar]

- 27.French S, Joseph S. Religiosity and its association with happiness, purpose in life, and self-actualisation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 1999;2:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman MJ. Disaster mental health research: Challenges for the future. In: Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, editors. Methods for disaster mental health research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:357–362. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, Jones RT, King DW, King LA, et al. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1427–1434. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galea S, Tracy M, Norris F, Coffey SF. Financial and social circumstances and the incidence and course of PTSD in Mississippi during the first two years after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:357–368. doi: 10.1002/jts.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallup Organization. Gallup/CNN/USA today/red cross poll # 2005–45: Hurricane Katrina survivors. Princeton: Gallup; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:190–200. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibbs MS. Factors in the victim that mediate between disaster and psychopathology: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1989;2:489–514. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giltay EJ, Zitman FG, Kromhout D. Dispositional optimism and the risk of depressive symptoms during 15 years of follow-up: The Zutphen elderly study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;91:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorsuch RL. Measurement: The boon and bane of investigating religion. American Psychologist. 1984;39:228–236. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill PC. Measurement in the psychology of religion and spirituality: Current status and evaluation. In: Paloutzian RF, Park CL, editors. Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 435–459. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill PL, Burrow AL, Brandenberger JW, Lapsley DK, Quaranto JC. Collegiate purpose orientations and well-being in early and middle adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. American Psychologist. 2003;58:64–74. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Nam CB, Ellison CG. Religious involvement and US adult mortality. Demography. 1999;36:273–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Idler EL, Kasl SV. Self-ratings of health: Do they also predict change in functional ability? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1995;508:S344–S353. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.6.s344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones-DeWeever A. Women in the wake of the storm: Examining the post-Katrina realities of the women of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast. Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaniasty K, Norris FH. Social support in the aftermath of disasters, catastrophes, and acts of terrorism: Altruistic, overwhelmed, uncertain, antagonistic, and patriotic communities. In: Ursano R, Fullerton C, editors. Bioterrorism: Psychological and public health interventions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2004. pp. 200–229. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaniasty K, Norris FH. Distinctions that matter: Received social support, perceived social support, and social embeddedness after disasters. In: Neria Y, Galea S, Norris F, editors. Mental health consequences of disasters. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-LT, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalances and trends in nonspecific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kessler RC, Galea S, Jones RT, Parker HA. Mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006;84:930–939. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.033019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koenig HG. Religion and medicine II: Religion, mental health, and related behaviors. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2001;31:97–109. doi: 10.2190/BK1B-18TR-X1NN-36GG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, George LK, Hays JC, Larson DB, Blazer DG. Attendance at religious services, interleukin-6, and other biological indicators of immune function in older adults. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1997;27:233–250. doi: 10.2190/40NF-Q9Y2-0GG7-4WH6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koenig HG, Hays JC, Larson DB, George LK, Cohen HJ, McCullough ME, et al. Does religious attendance prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3, 968 older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 1999;54A:M370–M376. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.m370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journal of Gerontology. 2002;57:332–347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krause N. Religious meaning and subjective well-being in late life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58:S160–S170. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krause N, Ellison CG, Shaw BA, Marcum JP, Boardman JD. Church-based social support and religious coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40:637–656. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lawson EJ, Thomas C. Wading in the waters: Spirituality and older Black Katrina survivors. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18:341–354. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levin JS, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Religious effects on health status and life satisfaction among Black Americans. Journal of Gerontology. 1995;50:154–163. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.3.s154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levy BR, Slade MD, Ranasinghe P. Causal thinking after a tsunami wave: Karma beliefs, pessimistic explanatory style and health among Sri Lankan survivors. Journal of Religion and Health. 2009;48:38–45. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim C, Putnam R. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review. 2010;75:914–933. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Little T, Cunningham W, Shahar G, Widaman K. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowe SR, Chan CS, Rhodes JE. Pre-disaster social support protects against psychological distress: A longitudinal analysis of Hurricane Katrina survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:551–560. doi: 10.1037/a0018317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maton KI, Wells EA. Religion as a community resource for well-being: Prevention, healing, and empowerment pathways. Journal of Social Issues. 1995;51:177–193. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Milam JE, Ritt-Oson A, Unger JB. Posttraumatic growth among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:192–204. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller WR, Thoresen CE. Spirituality, religion, and health. An emerging research field. American Psychologist. 2003;58:24–35. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morrow BH. Stretching the bonds: The families of Andrew. In: Peacock WG, Morrow BH, Gladwin H, editors. Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, gender, and the sociology of disasters. New York: Routledge; 1997. pp. 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Myer DG. The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist. 2000;55:56–67. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelson C, Jacobson C, Weinberger M, Bhaskaran V, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, et al. The role of spirituality in the relationship between religiosity and depression in prostate cancer patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;38:105–114. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9139-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Norris FH, Baker CK, Murphy AD, Kaniasty K. Social support mobilization and deterioration after Mexico’s 1999 flood: Effects of context, gender, and time. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Norris FH, Elrod CL. Psychological consequences of disaster: A review of past research. In: Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, editors. Methods for disaster mental health research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 20–44. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Norris F, Friedman M, Watson P. 60, 000 disaster victims speak: Part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry. 2002a;65:240–260. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Norris F, Friedman M, Watson P, Byrne C, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60, 000 disaster victims speak. Part I: An empirical review of the empirical literature. Psychiatry. 2002b;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Norris FH, Perilla JL, Riad JK, Kaniasty K, Lavizzo EA. Stability and change in stress, resources, and psychological distress following natural disaster: Findings from Hurricane Andrew. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 1999;12:363–396. doi: 10.1080/10615809908249317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oman D, Reed D. Religion and mortality among the community-dwelling elderly. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1469–1475. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pargament KI, Hahn J. God and the just world: Causal and coping attributions to God in health situations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1986;25:193–207. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pargament KI, Magyar-Russell G, Murray-Swank NA. The sacred and the search for significance: Religion as a unique process. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:665–687. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park CL. Religion and meaning. In: Paloutzian RF, Park CL, editors. Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality. New York: Guilford; 2005. pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology. 1997;12:115–144. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Patrick H, Ryan AM, Kaplan A. Early adolescents’ perception of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007;99:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peterson C, Seligman MEP, Vaillant G. Pessimistic explanatory style as a risk factor for physical illness: A thirtyfive year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:23–27. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pirraglia PA, Peterson JC, Williams-Russo P, Gorkin L, Charlson ME. Depressive symptomatology in coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1999;14:668–680. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199908)14:8<668::aid-gps988>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist. 2003;58:36–52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Puskar KR, Sereika SM, Lamb J, Tusaie-Mumford K, McGuinness T. Optimism and its relationship to depression, coping, anger, and life events in rural adolescents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1999;20:115–130. doi: 10.1080/016128499248709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rateau MR. Differences in emotional well-being of hurricane survivors: A secondary analysis of the ABC news Hurricane Katrina anniversary poll. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2009;23:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rhodes J, Chan C, Paxson C, Rouse CE, Waters M, Fussell E. The impact of Hurricane Katrina on the mental and physical health of low-income parents in New Orleans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rice KG, Herman MA, Petersen AC. Coping with challenge in adolescence: A conceptual model and psychoeducational intervention. Journal of Adolescence. 1993;16:235–251. doi: 10.1006/jado.1993.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rubonis AV, Bickman L. Psychological impairment in the wake of disaster: The disaster-psychopathology relationship. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:384–399. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Salloum A, Lewis M. An exploratory study of African American parent-child coping strategies post-Hurricane Katrina. Traumatology. 2010;16:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Salsman JM, Brown TL, Brechting EH, Carlson CR. The link between religion and spirituality and psychological adjustment: The mediating role of optimism and social support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:522–535. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sastry N, VanLandingham M. One year later: Mental illness prevalence and disparities among New Orleans residents displaced by Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:S725–S731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implication of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:201–228. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Scheier MF, Carver CS. On the power of positive thinking: The benefits of being optimistic. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1993;2:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges M. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scheier MF, Wrosch C, Baum A, Cohen S, Martire LM, Matthews KA, et al. The life engagement test: Assessing purpose in life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29:291–298. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Seligman MEP. Learned optimism. New York: Knopf; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sethi S, Seligman ME. Optimism and fundamentalism. Psychological Science. 1993;4:256–259. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J. Religiousness and depression: Evidence for amain effect and themoderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:614–636. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Smith BW, Pargament KI, Brant C, Oliver JM. Noah revisited: Religious coping by church members and the impact of the 1993 Midwest flood. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:169–186. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Solomon SD, Green BL. Mental health effects of natural and human-made disasters. PTSD Research Quarterly. 1992;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Solomon SD, Smith E, Robins LN, Fischbach RL. Social involvement as a mediator of disaster-induced stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1987;17:1092–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Spence PR, Lachlan KA, Griffin DR. Crisis communication, race, and natural disasters. Journal of Black Studies. 2007;37:539–554. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Steinglass P, Gerrity E. Natural disasters and posttraumatic stress disorder: Short-term versus long-term recovery in two disaster-affected communities. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1990;20:1746–1765. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:957–961. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sumer N, Karanci AN, Berument SK, Gunes H. Personal resources, coping self-efficacy, and quake exposure as predictors of psychological distress following the 1999 earthquake in Turkey. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:331–342. doi: 10.1002/jts.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Horowitz’s impact of event scale: Evaluation of 20 years of use. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:870–876. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000084835.46074.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Taylor RJ. Structural determinants of religious participation among Black Americans. Review of Religious Research. 1988;20:114–125. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Taylor RJ, Mattis J, Chatters LM. Subjective religiosity among African Americans: A synthesis of qualitative research and findings from five national samples. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25:524–543. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:455–472. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vernberg EM, La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Prinstein MJ. Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:237–248. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vilchinsky N, Kravetz S. How are religious belief and behavior good for you? An investigation of mediators relating religion to mental health in a sample of Israeli Jewish students. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44:459–471. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang P, Gruber MJ, Powers RE, Schoenbaum M, Speier AH, Wells KB, et al. Mental health service use among Hurricane Katrina survivors in the eight months after the disaster. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1403–1411. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.11.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Weaver AJ, Koenig HG, Ochberg FM. Posttraumatic stress, mental health professionals, and the clergy: A need for collaboration, training, and research. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:847–855. doi: 10.1007/BF02104106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Weems CF, Watts SE, Marsee MA, Taylor LK, Costa NM, Cannon MF, et al. The psychosocial impact of Hurricane Katrina: Contextual differences in psychological symptoms, social support, and discrimination. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2295–2306. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Weisler RH, Barbee JG, Townsend MH. Mental health and recovery in the Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina and Rita. JAMA. 2006;296:585–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.White IK, Philpot TS, Wylie K, McGowen E. Feeling the pain of mypeople: Hurricane Katrina, racial inequality, and the psyche of Black America. Journal of Black Studies. 2007;37:523–538. [Google Scholar]