Abstract

Neutrophilic inflammation might have a pathophysiological role in both carotid plaque rupture and ischemic stroke injury. Here, we investigated the potential benefits of the CXC chemokine-binding protein Evasin-3, which potently inhibits chemokine bioactivity and related neutrophilic inflammation in two mouse models of carotid atherosclerosis and ischemic stroke, respectively. In the first model, the chronic treatment with Evasin-3 as compared with Vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) was investigated in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice implanted of a ‘cast' carotid device. In the second model, acute Evasin-3 treatment (5 minutes after cerebral ischemia onset) was assessed in mice subjected to transient left middle cerebral artery occlusion. Although CXCL1 and CXCL2 were upregulated in both atherosclerotic plaques and infarcted brain, only CXCL1 was detectable in serum. In carotid atherosclerosis, treatment with Evasin-3 was associated with reduction in intraplaque neutrophil and matrix metalloproteinase-9 content and weak increase in collagen as compared with Vehicle. In ischemic stroke, treatment with Evasin-3 was associated with reduction in ischemic brain neutrophil infiltration and protective oxidants. No other effects in clinical and histological outcomes were observed. We concluded that Evasin-3 treatment was associated with reduction in neutrophilic inflammation in both mouse models. However, Evasin-3 administration after cerebral ischemia onset failed to improve poststroke outcomes.

Keywords: acute stroke, atherosclerosis, brain ischemia, carotid artery, inflammation

Introduction

Recent epidemiologic projections have indicated that cerebrovascular diseases will be the second cause of death (after ischemic heart diseases) in the world population in 2030.1 Since ischemic stroke is a relevant entity of cerebrovascular diseases that can provoke not only death, but also dramatic disabilities,2, 3 preventive strategies represent a hot-topic issue for both research and public health. Despite its highly frequent cardioembolic origin,4 ischemic stroke has been associated with the rupture of a vulnerable carotid plaque.5 Thus, an effective stroke prevention strategy has to increase atherosclerotic plaque stabilization. However, immediately after the cerebral ischemia onset, a pathophysiological cascade triggers the oxidative microvascular damage, blood–brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction, and postischemic inflammation, mediating the cerebral ischemic injury.6 Thus, a promising stroke treatment cannot leave out of cerebral tissue preservation from the ischemic insult. Since common inflammatory pathways have been recently indicated as promising pathophysiological targets for both prevention and treatment in ischemic stroke,7 we focused on the pharmacological inhibition of CXC chemokines (mainly CXCL1 and CXCL2, which have been shown as the major leukocyte chemoattractants and activators).8 In particular, we used the selective CXC chemokine-binding protein Evasin-3 (which has been recently shown to potently inhibit neutrophil-mediated cardiac injury after an acute myocardial infarction)9 to abrogate CXC chemokine bioactivity in both prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke. Two validated mouse models (shear stress-induced carotid atherogenesis developing both vulnerable and stable plaques and transient focal cerebral ischemia)10, 11 were used to assess the potential benefits of Evasin-3 on neutrophil-mediated atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability and poststroke cerebral injury, respectively.

Materials and methods

Prevention Strategy: Treatment with Evasin-3 in a Mouse Model of Shear Stress-Induced Atherogenesis and Plaque Vulnerability

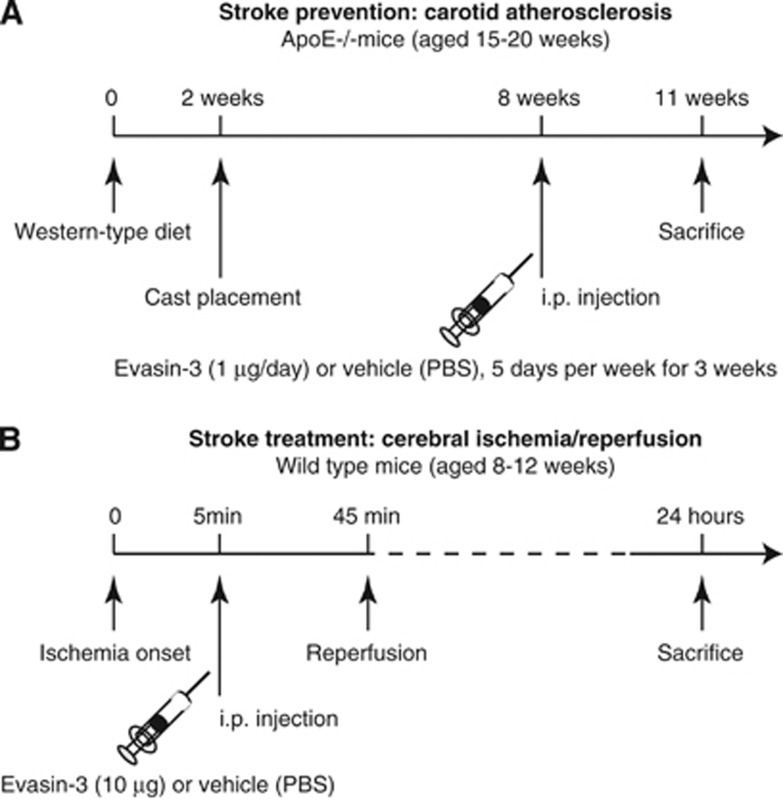

Apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice in a C57BL/6J background were obtained from The Charles River Laboratories (Lyon, France). Animals at 15 to 20 weeks of age were randomly assigned to receive either Vehicle (n=11) or the selective CXC chemokine-binding protein Evasin-3 (n=13) treatment. During the experimental period, all animals were fed a western-type diet consisting of 15% (wt/wt) cocoa butter and 0.25% (wt/wt) cholesterol (Diet W; abDiets). After a 2-week period of western diet, shear stress in the right common carotid artery was altered by cast placement, as previously described.11 Blood flow vortices (oscillatory shear stress (OSS) region) are produced by the cast stricture in the downstream common carotid artery. In addition, the constrictive stenosis decreases the blood flow, resulting in a low shear stress (LSS) region upstream from the cast. For the surgical procedure of cast implantation, the animals were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, and the anterior cervical triangles were accessed by a sagittal anterior neck incision. Nine weeks after surgery, the animals were euthanized to collect tissue and serum samples. During the last 3 weeks before euthanizing (from week 6 to 9 of cast implantation), mice were intraperitoneally injected with Evasin-3 (1 μg/day for 5 consecutive days per week, provided by Merck Serono, Geneva, Switzerland) or equivalent volume of control Vehicle (PBS, 200 μL/mouse) (Figure 1A). The dose of Evasin-3 administered was based on previous studies, showing marked efficacy to reduce in vivo neutrophil infiltration within inflamed tissues.8, 9 In selective experiments, to assess both intraplaque and systemic levels of CXCL1 and CXCL2, wild-type and ApoE−/− mice (n=5 to 7/group) were fed under normal diet for 28 weeks and followed without any surgical procedures till kill. No animal death was reported during the study protocols. These mouse protocols were approved by local ethics committee (‘Commision pour l'Experimentation Animale' of Canton Vaud) and Swiss authorities and conformed to the ‘position of the American Heart Association on Research Animal Use' and to ARRIVE guidelines.

Figure 1.

Evasin-3 treatment protocols. (A) Stroke prevention strategy with Evasin-3 treatment in the apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mouse model of shear stress-induced carotid atherogenesis and plaque vulnerability. (B) Stroke treatment strategy with Evasin-3 treatment in a cerebral ischemia/reperfusion model in wild-type mice. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Stroke Therapeutic Approach: Treatment with Evasin-3 in a Mouse Model of Acute Focal Brain Ischemia/Reperfusion

Adult wild-type (aged 8 to 12 weeks) C57BL/6J mice were temporarily anesthetized with 4% isoflurane and placed on a warm heating pad to maintain body temperature at 37±0.3°C. Anesthesia was maintained by nose cone with 1.5% isoflurane in 80% medical air/20% O2. After a midline skin incision, the left external carotid artery was exposed and its branches were electrocoagulated. A blunted monofilament nylon suture (Dafilon 6.0, Braun Medical AG, Sempach-Station, Switzerland) was introduced into the left internal carotid artery through the external carotid artery stump to occlude the middle cerebral artery. Interruption of regional cerebral blood flow in the middle cerebral artery territory was confirmed by documenting a >80% decrease in relative regional cerebral blood flow using laser Doppler flowmetry (Perimed AB, Stockholm, Sweden). Five minutes after ischemia onset, either Evasin-3 (at doses ranging from 1 to 10 μg/mouse) or equivalent volume of control Vehicle (PBS, 200 μL/mouse) was administered intraperitoneally to neutralize the bioactivity of CXC chemokine in vivo. The dose of Evasin-3 administered was based on previous studies, showing marked efficacy to reduce in vivo neutrophil infiltration within inflamed tissues.8, 9 After 45 minutes of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion, blood flow was restored by the withdrawal of the nylon suture (Figure 1B). A return to >50% of baseline regional cerebral blood flow within 5 minutes of suture withdrawal confirmed a reperfusion of the middle cerebral artery territory. Three animals (on total 117 animals used in the study) not meeting both ischemic and reperfusion flow criteria were excluded from the study. Only two animals (both treated with Evasin-3) died during the 24 hours of reperfusion. At different time points of reperfusion (up to 24 hours), animals were killed for infarct size determination or immunohistochemical analysis. This protocol was approved by local ethics committee (‘Commision d'Ethique de l'Experimentation Animale' of the University of Geneva) and Swiss authorities and conformed to the ‘position of the American Heart Association on Research Animal Use' and to ARRIVE guidelines.

Determination of Neurologic Deficits

Evaluation of neurologic deficits has been performed by a blinded observer 24 hours after surgical procedures.12, 13 Animals were scored neurologically, according to a 6-point scale: 0=no apparent neurologic deficit, 1=contra lateral forelimb flexion, 2=decreased grip of the contra lateral forelimb, 3=spontaneous movement in all directions, but contra lateral circling if pulled by tail, 4=spontaneous contra lateral circling, and 5=death.14, 15, 16

Infarct Volume and Brain Edema Measurements

Brains were cut in 20 μm coronal sections from the anterior to the posterior side. Every 150 μm, the brain sections were stained with a solution of 0.5% cresyl violet. Infarct size was obtained by summing infarct measurements on digital images of each section, acquired with an Epson perfection V750 scanner (Wädenswil, Switzerland), using ImageJ after compensation for edema as previously described.10 Brain edema was assessed on digital images by measuring the hemispheric enlargements as described previously.17 Infarct and hemispheric areas were manually drawn on digital images by a blinded operator using Adobe Photoshop.

Evans Blue Extravasation within the Ischemic Hemisphere

The BBB disruption was assessed after injection into the femoral vein of 4 mL/kg of Evans blue, prepared at a concentration of 2% in saline, immediately after reperfusion. The animals were euthanized 24 hours later. Quantitative analysis was performed with the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology, Bad Homburg, Germany) by measuring the total infrared emission of Evans blue on serial 30 μm coronal brain sections spanning the entire hemispheres.

Detection of Inflammatory Mediators in Mouse Serum

In mouse serum, levels of CXCL1, CXCL2, and pro-matrix metalloproteinase (pro-MMP)-9 were measured by colorimetric enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), following manufacturer's instructions. The limits of detection for ELISA were 15.625 pg/mL for CXCL1, 15.625 pg/mL for CXCL2, and 31.250 pg/mL for pro-MMP-9. Mean intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation were <8% for all markers. Serum triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were routinely measured and expressed in mmol/L.

Immunohistochemistry in Atherosclerotic Plaques and Infarcted Brain

Mouse carotid artery was macroscopically cut in three portions: region upstream of the cast device (LSS) and downstream of the cast (OSS) and frozen in Optimum Cutting Temperature (OCT). However, LSS and OSS portions and aortic sinus from all mice were serially cut in 5 μm transversal sections, as described previously.18 Cerebral coronal sections through the infarct area were cut at 20 μm. Sections from mouse specimens were fixed in acetone and immunostained with specific antibodies CD68 (macrophages, dilution: 1:400; ABD Serotec, Dusseldorf, Germany), anti-mouse Ly-6B.2 (neutrophils, dilution: 1:50; ABD Serotec), anti-mouse CXCL1 (dilution: 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-mouse CXCL2 (dilution: 1:13; R&D Systems) and anti-mouse MMP-9 (dilution: 1:60; R&D Systems). Quantifications were performed using the MetaMorph software (Visitron Systems, Puchleim, Germany). Results for other parameters were calculated as percentages of stained area on total lesion area or number of infiltrating cells per mm2 of lesion area.

Oil Red O Staining for Lipid Intraplaque Content

Eleven sections per mouse carotid LSS and OSS and five sections per mouse aortic sinus were stained with Oil Red O, as previously described.18 Sections and aortas were counterstained with Mayer's hemalun and rinsed in distilled water. Quantifications were performed using the MetaMorph software. Data were calculated as ratios of stained area on total lesion area.

Sirius Red Staining for Collagen Intraplaque Content

Eleven sections per mouse carotid LSS and OSS and five sections per mouse aortic sinus were rinsed with water and incubated with 0.1% Sirius red (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO, USA) in saturated picric acid for 90 minutes. Sections were rinsed twice with 0.01 N HCl for 1 minute and then immersed in water. After dehydration with ethanol for 30 seconds and coverslipping, the sections were photographed with identical exposure settings under ordinary polychromatic or polarized light microscopy. Total collagen content was evaluated under polychromatic light. Interstitial collagen subtypes were evaluated using polarized light illumination; under this condition thicker type I collagen fibers appeared orange or red, whereas thinner type III collagen fibers were yellow or green.19 Quantifications were performed with MetaMorph software. Data were calculated as percentages of stained area on total lesion area.

Oxidative Stress Determination

The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the infarcted brain hemispheres was assessed by immunostaining. Consecutive sections from the same brains were immunostained on their highly toxic product of lipid membrane peroxidation 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (mouse anti-4-HNE monoclonal antibody at 1 μg/mL; Oxis International Inc, Foster City, CA, USA)20 and for the neuroprotective 3,5-dibromotyrosine (mouse anti-Di bromo tyrosine monoclonal antibody at 10 μg/mL; AMS Biotechnology, Ltd, Abingdon, UK).21 Both stainings were performed as previously described in mouse hearts.20 To avoid any potential cross-reactivity with mouse heart antigens and to increase the specificity of the primary antibodies, the VECTOR M.O.M Immunodetection kit and the VECTOR VIP substrate kit for peroxidase (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) were used, following manufacturer's instructions. Quantification was performed with MetaMorph software. Results were expressed as percentages of stained area on total ischemic hemisphere surface area.

Real-Time RT-PCR

Total mRNA was isolated with Tri-reagent (Molecular Research Center (MRC), Cincinnati, OH, USA) from each mouse cerebral hemisphere. Reverse transcription was performed using the ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR (StepOne Plus, Applied Biosystems, Zweigniederlassung Zug, Switzerland) was performed with the ABsolute QPCR Mix (ABgene, ABgene Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Specific primers and probes (Supplementary Table 1) were used to determine the mRNA expression of neutrophil chemoattractants (Cxcl1 and Cxcl2), their selective receptors (Cxcr1 and Cxcr2), tumor necrosis factor (Tnf), interleukin-6 (Il6), neutrophil mediators (neutrophil elastase (Elane), matrix metalloproteinase (Mmp)-9, myeloperoxidase (Mpo)) and Hprt (housekeeping gene).18, 22 The fold change of mRNA levels was calculated by the comparative Ct method. The measured Ct values were first normalized to the Hprt internal control, by calculating a delta Ct (ΔCt). This was achieved by subtracting the GADPH Ct values from the gene of interest Ct value. A delta delta Ct (ΔΔCt) was calculated by subtracting the designated control ΔCt (right cerebral hemisphere) value from the study group ΔCt values. The ΔΔCt was then plotted as a relative fold change with the following formula: 2−ΔΔCt.

Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Extraction from the Ischemic Brain and Zymography

Brains were homogenized in five volumes (w/v) of 50 mmol/L Tris-saline buffer containing 5 mmol/L CaCl2. Protein concentrations were measured in the homogenates with a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Homogenates were then centrifuged and part of the supernatants was incubated for 60 minutes with gelatin-sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and centrifuged again. Gelatinases were eluted from the pellets with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and MMP activity was detected by gelatin zymography as previously described.17 Human pro-MMP-9 (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA, no. CC079) was loaded onto each gel as a standard. The MMP-9 concentration was assessed on inverted digital images by measuring the optical density of the bands with ImageJ. Data were expressed in arbitrary units.

Statistical Analysis

The Mann–Whitney nonparametric test (the normality assumption of the variables' distribution in both groups was violated) was used for comparisons of continuous variables and results were expressed as medians (interquartile range). Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were used to assess correlations. Values of P<0.05 (two-tailed) were considered as significant. All analyses were performed with GraphPad Instat software version 3.05 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Circulating and Tissue Levels of CXCL1 are upRegulated in Mouse Models of Carotid Atherosclerosis and Ischemic Stroke

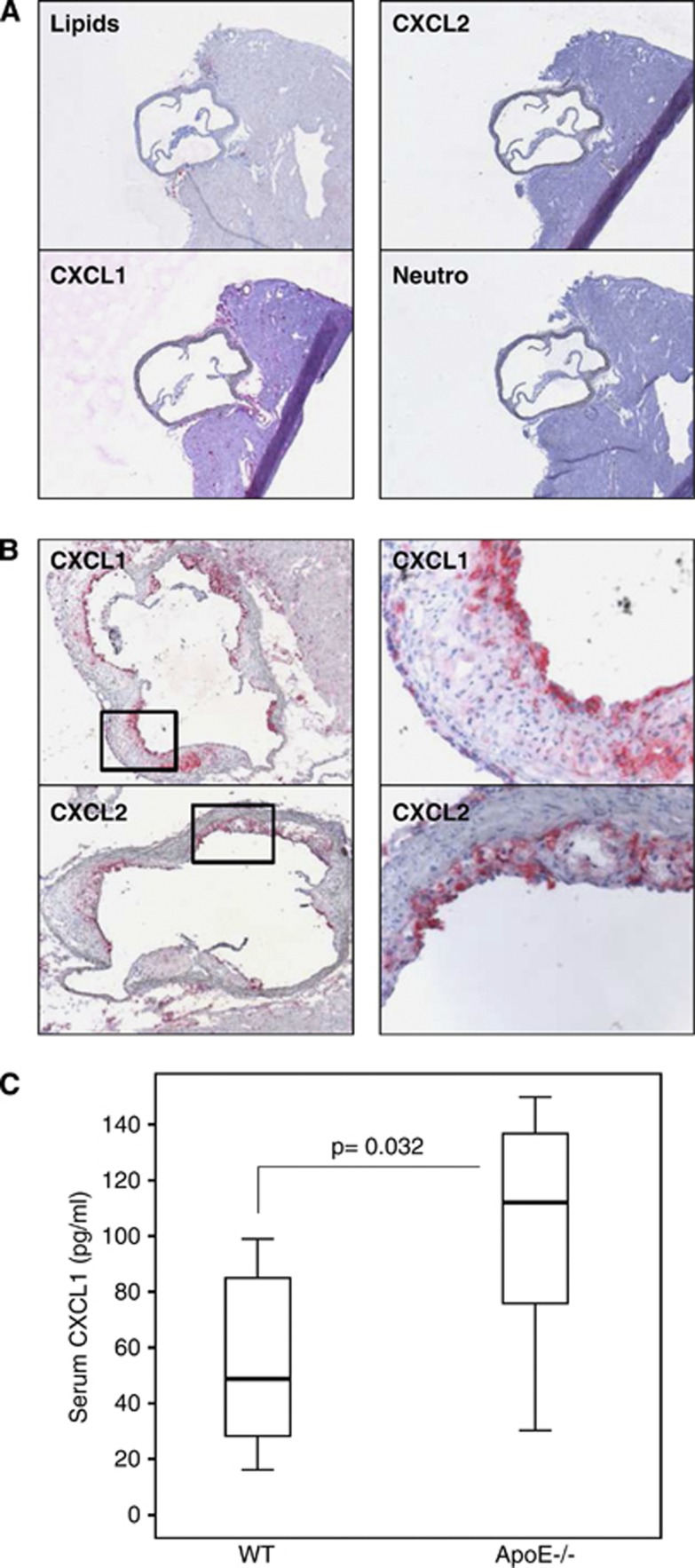

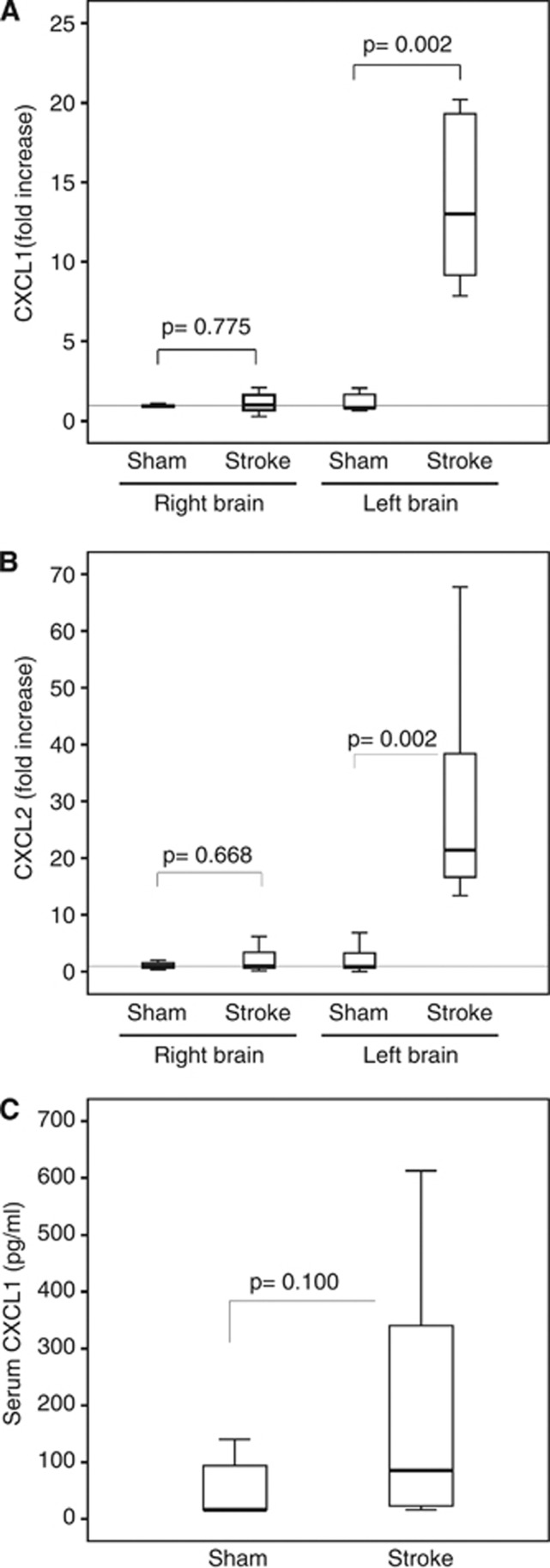

The levels of CXC chemokines were investigated in the systemic circulation, atherosclerotic plaques, and ischemic brain in the mouse models of carotid atherosclerosis (ApoE−/− mice) and ischemic stroke (wild-type mice). As predicted, wild-type mice did not develop atherosclerotic plaques (vessels negative for lipid and inflammatory cell stainings) in aortic roots (Figure 2A). Accordingly, CXCL1, CXCL2 as well as neutrophils were not detected in normal aortic roots from wild-type mice (Figure 2A). CXCL1 and CXCL2 proteins were well expressed within aortic root plaques from ApoE−/− mice (Figure 2B). CXCL1 serum levels were significantly increased in ApoE−/− mice (atherosclerotic model) as compared with age-matched wild-type mice (Figure 2C). CXCL1 and CXCL2 mRNA levels were markedly upregulated in the ischemic brain portion (left hemisphere) of mice subjected to 45 minutes of cerebral ischemia and 8 hours of reperfusion as compared with sham-operated animals (Figures 3A and 3B). At 24 hours of reperfusion, a nonsignificant (P=0.100) increase in CXCL1 serum levels was shown in cerebral ischemic mice as compared with sham-operated controls (Figure 3C). However, CXCL2 serum levels were found undetectable (below the lower range of detection: 15.625 pg/mL) in atherosclerotic and stroke models as well as in control wild-type mice (data not shown). In agreement with previously published data,7, 23 these results indicate that CXCL1 protein is upregulated at both systemic and tissue levels during atherogenesis. However, mRNA levels of both CXC chemokines (CXCL1 and CXCL2) are increased by ischemic injury in mouse brain.

Figure 2.

CXC chemokine levels are upregulated in serum and plaques of atherosclerotic mice. (A) Representative sections of aortic roots from wild-type mice, showing staining for lipids (Oil Red O), CXCL1, CXCL2, and neutrophils. (B) Representative sections of aortic root plaques from apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice showing staining for CXCL1 and CXCL2. On the right panel, representative higher magnifications ( × 20) of stained regions. (C) Serum CXCL1 levels in wild-type and ApoE−/− mice at 28 weeks of age under normal diet (n=5 to 7/group).

Figure 3.

Acute brain ischemia/reperfusion increases cerebral and circulating levels of CXC chemokines. Transient focal ischemia/reperfusion protocol was performed in the left brain hemisphere in male C57Bl/6 mice. Cerebral and serum levels of CXC chemokines were assessed in infarcted and sham-operated (Sham) mice. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range). (A) CXCL1 mRNA expression in the brain hemispheres at 8 hours of reperfusion. Relative expression normalized to Hprt was calculated with the comparative Ct method and shown as fold change of mRNA levels (n=6 to 8/group). (B) CXCL2 mRNA expression in the brain hemispheres at 8 hours of reperfusion. Relative expression normalized to Hprt was calculated with the comparative Ct method and shown as fold change of mRNA levels (n=6 to 8/group). (C) Serum CXCL1 levels at 24 hours of reperfusion (n=6 in Sham and n=17 in infarcted mice).

Treatment with Evasin-3 Reduces Histologic Parameters of Plaque Vulnerability in a Mouse Model of Shear Stress-Induced Carotid Atherosclerosis

The selective inhibition of CXC chemokine bioactivities in stroke prevention was first assessed in a mouse model of carotid atherogenesis, characterized by both vulnerable and stable plaques.11 The bioactivity of each Evasin-3 batch was verified before use by verifying Evasin-3-mediated inhibition of CXCL1 and CXCL2 bioactivity in vitro using mouse neutrophil microchemotaxis assay (data not shown). Six weeks after the cast placement, ApoE−/− mice were treated for 3 weeks with Evasin-3 or Vehicle and then euthanized for the histologic analysis of plaque vulnerability in the aortic roots and in the LSS and OSS regions of carotid arteries. At kill, no significant differences were found between Evasin-3- and Vehicle-treated mice in terms of body weight and lipid profile (Supplementary Table 2). To further investigate the potential concomitant reduction in the vascular and serum levels of CXC chemokines associated with Evasin-3 treatment, we measured these molecules in mouse samples at kill. No significant differences were found between Evasin-3- and Vehicle-treated mice regarding CXCL1 (both serum and intraplaque protein) and CXCL2 (intraplaque protein) expression (Supplementary Table 3). Importantly, CXCL2 serum levels in ApoE−/− mice were confirmed below the lower range of detection of the ELISA kit (<15.625 pg/mL), suggesting CXCL1 to have a more relevant role in atherosclerosis. Evasin-3 treatment did not induce any effect on lipid content in LSS carotid and aortic root plaques (Table 1; Supplementary Figures 1A and 1B). A slight decrease in lipid content was associated with Evasin-3 treatment in OSS carotid plaques (Table 1; Supplementary Figure 1A). No difference between treatment groups was observed on macrophage intraplaque content in both carotid and aortic sinus (Table 1; Supplementary Figures 2A and 2B). In carotid plaques (both LSS and OSS) and aortic sinus, Evasin-3 treatment abrogated neutrophil infiltration (Table 1; Supplementary Figures 3A and 3B) as compared with control Vehicle. No significant difference in intraplaque collagen content was shown between Evasin-3- and Vehicle-treated mice in both LSS and OSS carotid plaques (Table 1; Supplementary Figures 4A and 4B). Conversely, Evasin-3 treatment was associated with a marked increase in collagen content in aortic root plaques (Table 1; Supplementary Figures 4A and 4B). Lower MMP-9 intraplaque content in both OSS and LSS carotid plaques was shown in Evasin-3-treated mice as compared with control Vehicle (Table 1; Supplementary Figures 5A and 5B). No statistically significant effect on MMP-9 intraplaque content was induced by Evasin-3 treatment in aortic roots (Table 1; Supplementary Figures 5A and 5B). Taking together, these results indicate that in vivo systemic CXC chemokine inhibition with the selective CXC chemokine-binding protein Evasin-3 was associated with a weak improvement of neutrophilic intraplaque inflammation potentially associated with mouse plaque vulnerability.18

Table 1. Parameters of mouse plaque vulnerability.

| Parameters | Vehicle-treated mice (n=11) | Evasin-3-treated mice (n=13) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid LSS | |||

| Oil Red O, × 103 μm2 | 393.88 (227.52–971.66) | 217.32 (168.23–376.91) | 0.192 |

| Macrophage+ area, % | 12.69 (8.81–27.76) | 13.79 (5.68–23.78) | 0.664 |

| Neutrophils/mm2 | 10.89 (2.10–18.58) | 1.05 (0.19–2.78) | 0.005 |

| Total collagen, % | 14.07 (10.56–19.92) | 17.12 (15.28–25.96) | 0.052 |

| MMP-9, % | 5.22 (2.50–9.23) | 1.04 (0.27–2.12) | 0.006 |

| Carotid OSS | |||

| Oil Red O, × 103 μm2 | 325.73 (199.70–592.09) | 175.08 (128.63–245.40) | 0.035 |

| Macrophage+ area, % | 3.30 (2.66–4.59) | 4.50 (2.25–28.88) | 0.510 |

| Neutrophils/mm2 | 5.36 (0.67–8.70) | 0.21 (0.10–2.43) | 0.048 |

| Total collagen, % | 18.63 (15.46–24.29) | 22.55 (17.20–28.17) | 0.210 |

| MMP-9, % | 4.17 (2.24–7.84) | 0.40 (0.28–1.83) | 0.005 |

| Aortic roots | |||

| Oil Red O, × 103 μm2 | 332.92 (242.93–478.84) | 286.56 (230.98–452.48) | 0.758 |

| Macrophage+ area, % | 21.83 (19.90–34.40) | 29.00 (20.76–39.89) | 0.356 |

| Neutrophils/mm2 | 13.71 (11.35–20.54) | 7.03 (3.22–12.37) | 0.036 |

| Total collagen, % | 6.88 (5.12–13.20) | 16.62 (9.91–22.46) | 0.036 |

| MMP-9, % | 11.14 (6.89–16.76) | 6.99 (3.08–8.61) | 0.065 |

LSS, low shear stress; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; OSS, oscillatory shear stress.

Data are expressed as medians (interquartile range).

Treatment with Evasin-3 Does Not Affect CXC Chemokine Levels and Cerebral Injury in a Mouse Model of Cerebral Transient Focal Ischemia/Reperfusion

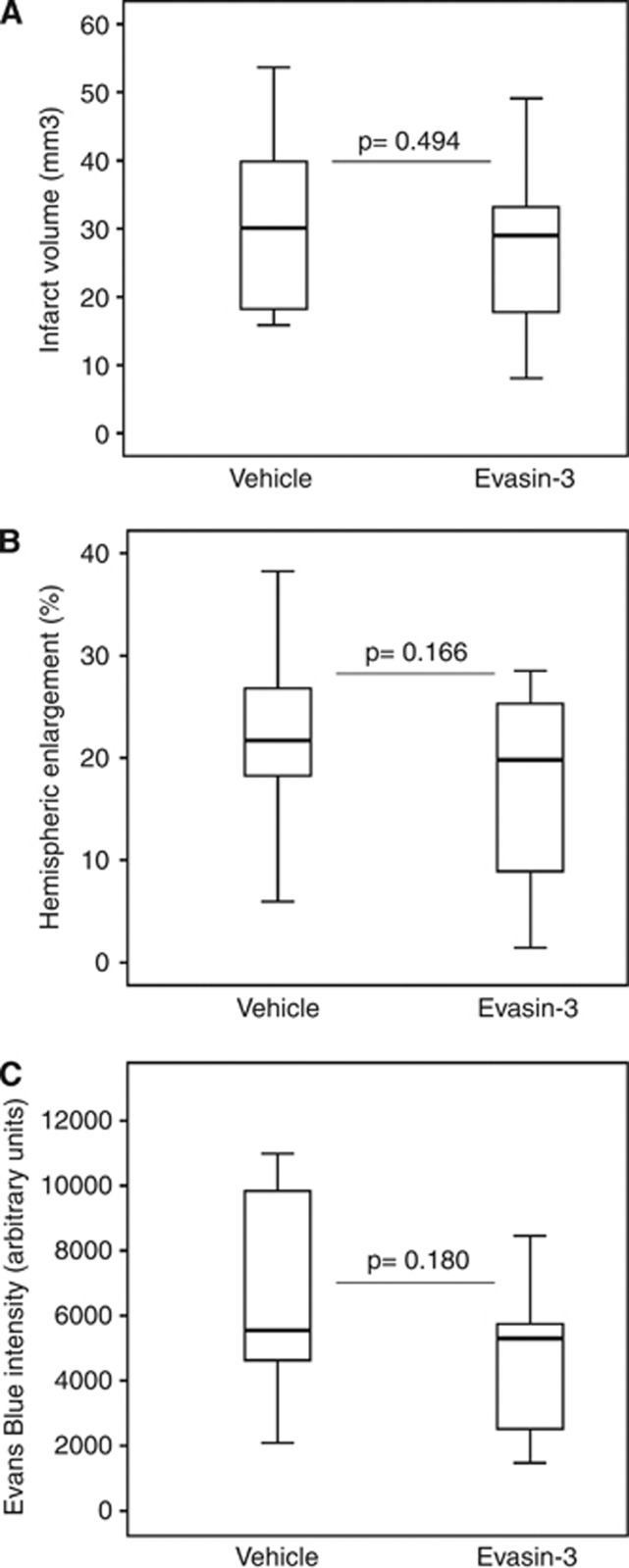

Evasin-3 has been shown to mainly inhibit CXC chemokine bioactivity rather than tissue and serum levels.8, 9 In the stroke model, the bioactivity of each Evasin-3 batch was verified in vitro using mouse neutrophil chemotaxis assay before use (data not shown). To further confirm the neutralizing properties of Evasin-3, we also investigated if Evasin-3 treatment (a single intraperitoneal dose (10 μg/mouse), administered 5 minutes after the initiation of 45-minute cerebral ischemia) was associated with modifications in CXC chemokine levels in the brain 24 hours after stroke. As shown in Supplementary Figures 6A to 6D, the mRNA levels of CXC chemokines (CXCL1 and CXCL2) and their receptors (CXCR1 and CXCR2) in the ischemic hemisphere were not significantly altered by Evasin-3 as compared with control Vehicle. The potential benefit of Evasin-3 treatment in poststroke cerebral injury (assessed by infarct size, brain edema, and BBB permeability measurements) was then investigated by treating mice with a single intraperitoneal dose of Evasin-3 (1 to 10 μg/mouse) or control Vehicle (PBS). Evasin-3 treatment did not significantly improve the clinical neurological outcomes (assessed by a validated neurologic score) at 12 hours as well as 24 hours after stroke (Supplementary Table 4). Red blood cell, white blood cell, and platelet counts were not altered by Evasin-3 treatment as compared with control Vehicle (Supplementary Table 4). Evasin-3 administration did not significantly reduce cerebral infarct size as compared with Vehicle (Figure 4A). Accordingly, Evasin-3 treatment did not affect poststroke brain edema (Figure 4B) and BBB permeability (Figure 4C) as compared with Vehicle, indicating that the single administration of Evasin-3 failed to improve early injury in poststroke treatment.

Figure 4.

Treatment with Evasin-3 does not affect cerebral infarct size, edema, and blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability. Evasin-3 (10 μg/mouse) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Vehicle) was administered 5 minutes after ischemia onset. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range). (A) Quantification of infarct size after 24 hours of reperfusion (n=16 to 20/group). (B) Quantification of ipsilateral hemispheric enlargements within the ischemic hemispheres after 24 hours of reperfusion (n=16 to 20/group). (C) Quantification of Evans blue fluorescent intensity within the infarcted hemisphere (n=6/group).

Single Administration of Evasin-3 Inhibits Poststroke Neutrophil Recruitment, But Not Neutrophil Activation within the Infarcted Brain

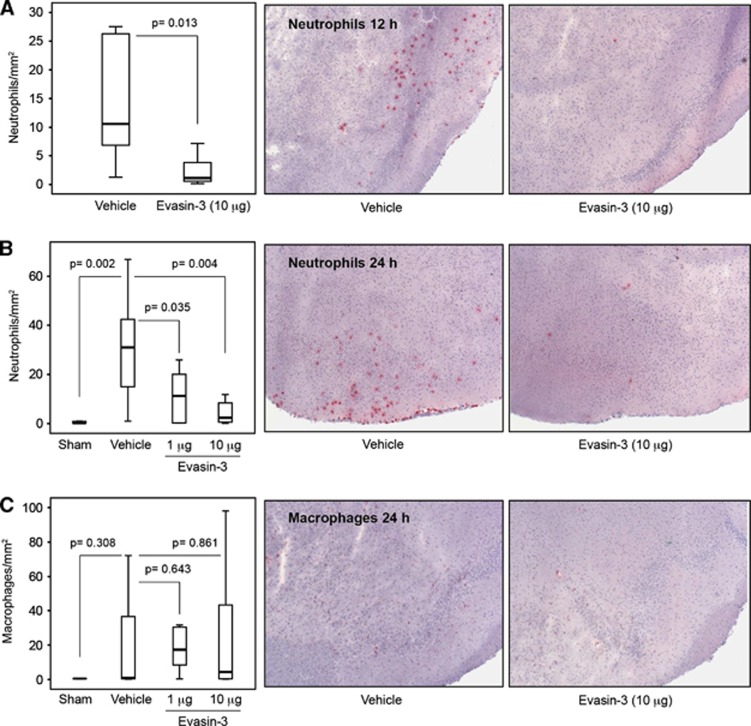

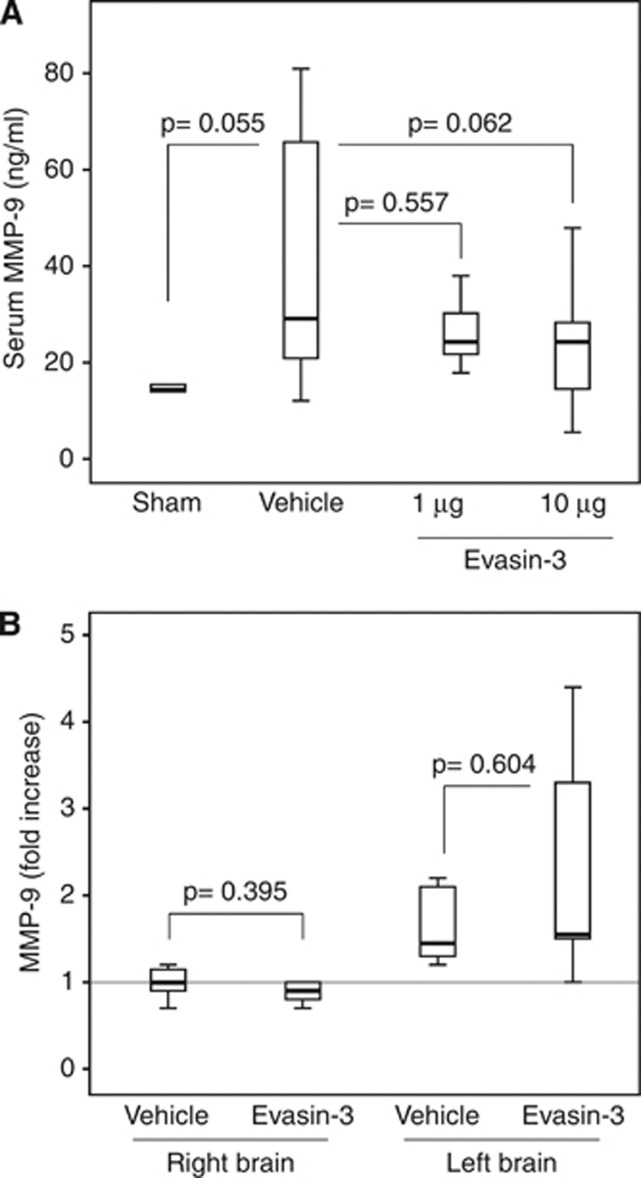

Leukocyte infiltration in ischemic left brain hemisphere was assessed at 12 and 24 hours of reperfusion. High-dose (10 μg/mouse) Evasin-3 treatment significantly reduced neutrophil (Ly-6B.2+ cell) infiltration already after 12 hours of reperfusion as compared with Vehicle (Figure 5A). At 24 hours of reperfusion, brain ischemia was associated with a remarkable cerebral infiltration of neutrophils as compared with sham-operated group (Figure 5B). Evasin-3 treatment (at both low (1 μg/mouse) and high (10 μg/mouse) doses) abrogated neutrophil infiltration within the ischemic brain hemisphere (Figure 5B). No effect on macrophage (CD68+ cell) recruitment was shown in the different treatment groups as compared with control Vehicle or sham-operated mice (Figure 5C), indicating that selective inhibition of CXC chemokine bioactivity mainly affect neutrophil recruitment within inflamed or infarcted peripheral tissues.8, 9 The production of some neutrophilic products (such as MMP-9, MMP-8, Neutrophil elastase, and myeloperoxidase, previously shown to increase brain and cardiovascular injuries)10, 18 within the infarcted brain hemispheres was also investigated. Evasin-3 treatment failed to significantly reduce pro-MMP-9 serum levels as compared with control Vehicle at 24 hours of reperfusion (Figure 6A). Accordingly, Evasin-3 administration had no effect in tissue MMP-9 mRNA expression (Figure 6B) and gelatinolytic activity (Supplementary Figures 7A and 7B) in both brain hemispheres as compared with control Vehicle. Similarly, Evasin-3 treatment did not affect the cerebral mRNA expression level of different neutrophil granule products (such as Neutrophil Elastase, MMP-8, and myeloperoxidase) (Supplementary Figures 8A to 8C). Given the potential association between neutrophilic inflammation and the release of potential mediators of ischemic injury (such as some ROS and inflammatory molecules) during reperfusion within brain and heart,20, 24 we also investigated the expression of these mediators during the postischemic period. In particular, the expression of the neuroprotective mediator dibromotyrosine was also assessed.21 Evasin-3 treatment reduced dibromotyrosine-positive immunostaining (Supplementary Figures 9A and 9B), but not 4-HNE-positive areas (Supplementary Figures 9C and 9D) within the infarcted hemisphere as compared with Vehicle. Similarly to what was observed in infarcted hearts,20 neutrophil cerebral infiltration positively correlated with dibromotyrosine-positive areas (r=0.8182, P=0.003), but not with 4-HNE levels (r=−0.4912, P=0.053). Moreover, Evasin-3 treatment did not induce any significant effect on the mRNA expression of TNF (Supplementary Figure 10A) and IL-6 (Supplementary Figure 10B) within the infarcted brain when compared with control Vehicle.

Figure 5.

Treatment with Evasin-3 reduces neutrophil cerebral infiltration during reperfusion. The transient focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion protocol was performed in male sham-operated (Sham), Evasin-3-, or Vehicle-treated wild-type mice. Evasin-3 (1 or 10 μg/mouse) or Vehicle was administered 5 minutes after ischemia onset. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range). (A) Left panel: quantification of infiltrated neutrophils per area in frozen sections of infarcted hemispheres at 12 hours of reperfusion (n=7/group). Right panel: representative images of cerebral neutrophil (Ly-6B.2+ cell) infiltration at 12 hours of reperfusion are shown. (B) Left panel: quantification of infiltrated neutrophils per area in frozen sections of infarcted hemispheres at 24 hours of reperfusion (n=5 to 12/group). Right panel: representative images of neutrophil infiltration at 24 hours of reperfusion are shown. (C) Left panel: quantification of infiltrated macrophages per area in frozen sections of infarcted hemispheres at 24 hours of reperfusion (n=5 to 12/group). Right panel: representative images of macrophage (CD68+ cell) infiltration at 24 hours of reperfusion are shown.

Figure 6.

Treatment with Evasin-3 does not affect serum levels and the cerebral expression of metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) after stroke. Evasin-3 (1 or 10 μg/mouse) or Vehicle was administered 5 minutes after ischemia onset. Cerebral and serum levels of MMP-9 were assessed at 24 hours of reperfusion. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range). (A) Serum levels of pro-MMP-9 (n=5 to 17/group). (B) mRNA expression of MMP-9 in the brain hemispheres. Relative expression normalized to Hprt was calculated with the comparative Ct method and shown as fold change of mRNA levels (n=6 to 8/group).

Discussion

Evasin-3 Treatment in Carotid Atherosclerosis

The major finding of the present article is the remarkable efficacy of the selective inhibition of CXCL1 and CXCL2 with Evasin-3 as a potential prevention treatment of ischemic stroke because of carotid atherosclerosis. After having confirmed that CXC chemokines were markedly upregulated in both systemic circulation and atherosclerotic plaques of ApoE−/− mice,23 we showed that their selective pharmacological inhibition was associated with the improvement of histologic parameters of plaque vulnerability. Similar results were obtained in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis,8 a chronic treatment approach with low-dose Evasin-3 (5 daily injections of 1 μg/mouse per week for total 3 weeks of treatment) abrogated neutrophil infiltration and activation within the peripheral inflamed tissues (both carotid and aortic root atherosclerotic plaques). Importantly, Evasin-3-mediated inhibition of neutrophil activation was supported by the reduction in the intraplaque content of the neutrophilic granule enzyme MMP-9. This effect was observed in both aortic root and carotid atherosclerotic plaques, previously shown as characterized by different degree profiles of vulnerability.12 Since this neutrophilic protease has been described to induce a ‘cannibal' digestion of protective collagen products within atherosclerotic plaques,18 we also considered the potential effects of Evasin-3 treatment on intraplaque collagen. Despite a weak effect, we observed a significant increase in collagen deposition in aortic root plaques in Evasin-3-treated mice as compared with controls. Since final intraplaque collagen content results from the complex balance between its production and degradation, we cannot exclude that the selective but limited beneficial effect of Evasin-3 was probably influenced by a complementary activation/inhibition of other cell players within atherosclerotic plaques. In particular, CXC chemokine-mediated activation of smooth muscle cells and macrophages in the atherosclerotic microenvironment might counteract the potentially protective neutrophil inhibition, resulting in a modest final effect on the stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques. Intriguingly, Evasin-3 treatment was not associated with reduction in macrophage intraplaque infiltration. Since CXC chemokine-mediated macrophage recruitment within atherosclerotic plaques was previously described in mice,23, 25 these data were partially surprisingly. However, given the redundancy of chemokine system, we cannot exclude that a chronic anti-chemokine treatment (i.e., Evasin-3) might induce a compensatory upregulation of other chemoattractants or chemokine receptors responsible for macrophage intraplaque recruitment.26 Another limitation of the present study is represented by the assessment of mouse plaque vulnerability based on histologic surrogate biomarkers, instead of clinical cardiovascular outcomes (i.e., acute cerebral events). Since ApoE−/− mice have been shown to develop accelerated atherogenesis (also associated with microglial inflammation),27, 28, 29 but not spontaneous ischemic events in the life time comparable to our shear stress-induced protocol (max 31 weeks of age), we were not able to assess carotid plaque vulnerability on the basis of a clinical thrombotic rupture. Therefore, despite highly speculative, the use of Evasin-3 in stroke prevention (targeting carotid atherogenesis) showed that the selective CXC chemokine inhibition potently abrogates atherosclerosis-related neutrophilic inflammation, potentially resulting in less inflamed and more stable plaques.

Evasin-3 Treatment in Ischemic Stroke

Given the partial successful results observed in stroke prevention, we also investigated the potential protective role of the selective CXC chemokine inhibition as a stroke treatment. In fact, poststroke cerebral infiltration of neutrophils has been previously described as a potential pathophysiological feature mediating ischemic brain injury.30 In addition, neutrophil products (such as MMP-9) have been indicated as pivotal mediators of postischemic cerebral damage and hemorrhagic transformation.31 Although the source of MMP-9 within the infarcted cerebral tissue remains a matter of debate,31, 32 neutrophils have been clearly shown as probable candidates.32 Since neutrophils have been shown to be differently activated in culture condition mimicking the systemic circulation and in adherence to an inflamed tissue,33 we assessed MMP-9 levels in both serum and within the infarcted brain. Considering this common background on neutrophil infiltration within both vulnerable plaques and ischemic brain, we investigated Evasin-3 treatment to also abrogate neutrophil recruitment and activation within the ischemic hemisphere. The treatment protocol and doses (single administration of 1 or 10 μg/mouse) were selected on the basis of recent successful results of Evasin-3 in a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction.9 We also investigated if CXCL1 and CXCL2 were upregulated in both systemic circulation and ischemic brain by acute ischemic stroke in our mouse model of transient focal cerebral ischemia.10 Our results showed that both CXC chemokines were significantly increased already 8 hours after ischemia onset. However, both serum CXCL1 and CXCL2 levels were not significantly modified by the ischemic cerebral event in the first 24 hours. These results indicated that a ‘true' chemoattractant gradient toward the ischemic brain might be established during reperfusion, thus, favoring neutrophil transmigration and infiltration. The results confirmed this hypothesis, showing that Evasin-3 treatment (neutralizing CXC chemokine bioactivity instead of tissue and serum levels) significantly reduced the cerebral infiltration of neutrophils at both 12 and 24 hours after the ischemia onset as compared with control Vehicle. At 24 hours of reperfusion, neutrophil infiltration was positively associated with the production of certain ROS (dibromotyrosine-positive area) in the infarcted hemispheres. Although we did not provide direct evidence on Evasin-3 accumulation within the infarcted brain, the reduction in cerebral neutrophil infiltration during reperfusion (associated with Evasin-3) might represent a proof of the pharmacologic efficacy of this drug, which neutralizes CXC chemokine gradient from the blood stream toward the infarcted brain. However, Evasin-3 treatment was not associated with further beneficial effects on the systemic and cerebral expression of other neutrophil products (i.e., MMP-9) and inflammatory mediators of brain injury (i.e., TNF and IL-6)24 nor with clinical and histological improvements in stroke size, brain edema, and BBB dysfunction. These data suggest that, despite statistically significant, the reduction in neutrophil infiltration was not ‘clinically relevant' for improving poststroke outcomes. Differently from acute myocardial infarction,9, 20 these data also raised some questions on the real pathophysiological importance of the neutrophilic inflammation in poststroke neuroprotection. In fact, potent neutrophilic mediators might be differently activated by heart or brain ischemia, suggesting that the reduction in the number of infiltrated neutrophils might not be necessarily related to the degree of their activation. In addition, neutrophils might also indirectly increase (via ROS release)20 the production of some neuroprotective mediators, such as dibrotyrosine.21 This endogenous halogenated derivative the aromatic amino acid ℒ-Phenylalanine has been recently shown to protect neurons from ischemic brain injury in rats.21 Thus, beside that fact Evasin-3 treatment did not improve the cerebral levels of specific inflammatory mediators of cerebral injury (such as proteases, TNF, IL-6, and other oxidants),24, 34 the selective reduction in neutrophilic ROS in the presence of Evasin-3 treatment might even be deleterious for the ischemic brain.20, 33 Our results are in partial contrast with previous studies indicating that the abrogation of poststroke neutrophil cerebral infiltration might be a promising therapeutic target to reduce brain injury during reperfusion.21, 35 However, although the majority of the article focused on neutrophil infiltration, less is known on the selective release and expression of neutrophilic products that might increase the cerebral ischemic injury.36 Finally, no evidence on a direct protective role of CXC chemokine inhibition on neurons or microglial cells has been clearly shown in the animal models of ischemic stroke.37 Our results showed that, although Evasin-3-mediated neutralization of CXC chemokine bioactivity result in a reduction in neutrophil infiltration after stroke, the potential beneficial effect was weak. We believe that neutrophils might induce both protective and deleterious effects in the infarcted brain.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that treatment with Evasin-3 (that neutralizes in vivo and in vitro bioactivity of CXCL1 and CXCL2) selectively reduced neutrophilic inflammation and potentially related plaque vulnerability in mice. CXC chemokines inhibition should be also considered to abrogate the intraplaque neutrophilic release of MMP-9. This therapeutic approach might represent a promising prevention strategy against ischemic stroke caused by carotid atherosclerotic stenosis. Despite this relevant role in atherogenesis, Evasin-3 treatment has a marginal role in stroke treatment. In fact, no poststroke clinical outcomes were improved by CXC chemokine inhibition as compared with controls. Evasin-3 treatment was selectively associated with reduction in poststroke neutrophil infiltration. This potential histologic improvement was accompanied by the absence of reduction in neutrophilic mediators of cerebral injury and the concomitant inhibition of the neuroprotective dibromotyrosine. Given these weak modifications associated with Evasin-3 treatment during poststroke early phases, the selective inhibition of CXC chemokine pathway might be of particular importance to prevent carotid plaque rupture, but not ischemic brain injury.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism website (http://www.nature.com/jcbfm)

This research was funded by the Brazilian Swiss Joint Research Program (BSJRP) to Dr F Mach, Dr N Stergiopulos, and AS Robson. This research was funded by EU FP7, Grant number 201668, AtheroRemo to Dr F Mach. This work was also supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation Grants to Dr F Mach (#310030-118245) and Dr F Montecucco (#32003B-134963/1). This work was also supported by a Grant from Novartis Foundation to Dr F Montecucco.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. e442. 2006;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevalence of stroke—United States, 2006-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:379–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn RW, MacWalter RS, Doney AS. The cost of cerebral ischaemia. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, Markus HS. Doppler embolic signals in cerebrovascular disease and prediction of stroke risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:3711–3717. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.563056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkind MS. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and stroke. Neurologist. 2006;12:140–148. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000215789.70804.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A, Hofer M. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: therapeutic approaches. J Transl Med. 2009;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabelli-Badenier M, Braunersreuther V, Viviani GL, Dallegri F, Quercioli A, Veneselli E, et al. CC and CXC chemokines are pivotal mediators of cerebral injury in ischaemic stroke. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:409–420. doi: 10.1160/TH10-10-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déruaz M, Frauenschuh A, Alessandri AL, Dias JM, Coelho FM, Russo RC, et al. Ticks produce highly selective chemokine binding proteins with antiinflammatory activity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2019–2031. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecucco F, Lenglet S, Braunersreuther V, Pelli G, Pellieux C, Montessuit C, et al. Single administration of the CXC chemokine-binding protein Evasin-3 during ischemia prevents myocardial reperfusion injury in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1371–1377. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.206011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copin JC, Goodyear MC, Gidday JM, Shah AR, Gascon E, Dayer A, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in apoptosis after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats and mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1597–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, van der Baan A, Grosveld F, Daemen MJ, et al. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation. 2006;113:2744–2753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardehali MR, Rondouin G. Microsurgical intraluminal middle cerebral artery occlusion model in rodents. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;107:267–275. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata R, Mies G, Wiessner C, Fritze K, Hesselbarth D, Brinker G, et al. A reproducible model of middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice: hemodynamic, biochemical, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:367–375. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidday JM, Gasche YG, Copin JC, Shah AR, Perez RS, Shapiro SD, et al. Leukocyte-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates blood-brain barrier breakdown and is proinflammatory after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H558–H568. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01275.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Tsuji M, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski H. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: evaluation of the model and development of a neurologic examination. Stroke. 1986;17:472–476. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Irie K, Anwer MS, Fisher M. Delayed triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining remains useful for evaluating cerebral infarct volume in a rat stroke model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:1132–1135. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199710000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copin JC, Merlani P, Sugawara T, Chan PH, Gasche Y. Delayed matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces intracerebral hemorrhage after embolic stroke in rats. Exp Neurol. 2008;213:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecucco F, Di Marzo V, da Silva RF, Vuilleumier N, Capettini L, Lenglet S, et al. The activation of the cannabinoid receptor type 2 reduces neutrophilic protease-mediated vulnerability in atherosclerotic plaques. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:846–856. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisby M, Nordin-Fredriksson G, Shah PK, Yano J, Zhu J, Nilsson J. Pravastatin treatment increases collagen content and decreases lipid content, inflammation, metalloproteinases, and cell death in human carotid plaques: implications for plaque stabilization. Circulation. 2001;103:926–933. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecucco F, Bauer I, Braunersreuther V, Bruzzone S, Akhmedov A, Lüscher TF, et al. Inhibition of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase reduces neutrophil-mediated injury in myocardial infarction Antioxid Redox Signal 2012. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kagiyama T, Glushakov AV, Sumners C, Roose B, Dennis DM, Phillips MI, et al. Neuroprotective action of halogenated derivatives of L-phenylalanine. Stroke. 2004;35:1192–1196. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125722.10606.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecucco F, Vuilleumier N, Pagano S, Lenglet S, Bertolotto M, Braunersreuther V, et al. Anti-Apolipoprotein A-1 auto-antibodies are active mediators of atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:412–421. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert WA, Santiago R, Curtiss LK, Terkeltaub RA. A leukocyte homologue of the IL-8 receptor CXCR-2 mediates the accumulation of macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions of LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:353–363. doi: 10.1172/JCI1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmerbach K, Schefe JH, Krikov M, Müller S, Villringer A, Kintscher U, et al. Comparison between single and combined treatment with candesartan and pioglitazone following transient focal ischemia in rat brain. Brain Res. 2008;1208:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, de Boer HC, Segers D, Huisman M, et al. Shear stress-induced changes in atherosclerotic plaque composition are modulated by chemokines. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:616–626. doi: 10.1172/JCI28180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunersreuther V, Zernecke A, Arnaud C, Liehn EA, Steffens S, Shagdarsuren E, et al. Ccr5 but not Ccr1 deficiency reduces development of diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:373–379. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000253886.44609.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama J, Faraci FM, Lentz SR, Heistad DD. Cerebral vascular dysfunction during hypercholesterolemia. Stroke. 2007;38:2136–2141. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.481879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisby M, Rahman SM, Sylvén C, Winblad B, Schultzberg M. Effects of high cholesterol diet on gliosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Implications for Alzheimer's disease and stroke. Neurosci Lett. 2004;369:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Uscio LV, Smith LA, Katusic ZS. Hypercholesterolemia impairs endothelium-dependent relaxations in common carotid arteries of apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Stroke. 2001;32:2658–2664. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.097393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly ES, Winfree CJ, Springer TA, Naka Y, Liao H, Yan SD, et al. Cerebral protection in homozygous null ICAM-1 mice after middle cerebral artery occlusion. Role of neutrophil adhesion in the pathogenesis of stroke. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:209–216. doi: 10.1172/JCI118392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Guo Q, Hossain M, Fazio V, Zeynalov E, Janigro D, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells are the major source of MMP-9 contributing to blood-brain barrier dysfunction and infarct formation after ischemic stroke in mice. Brain Res. 2009;1294:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell A, Cuadrado E, Ortega-Aznar A, Hernández-Guillamon M, Lo EH, Montaner J. MMP-9-positive neutrophil infiltration is associated to blood-brain barrier breakdown and basal lamina type IV collagen degradation during hemorrhagic transformation after human ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:1121–1126. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quercioli A, Mach F, Bertolotto M, Lenglet S, Vuilleumier N, Galan K, et al. Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) increases the release of neutrophil products associated with coronary vulnerability. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:124–139. doi: 10.1160/TH11-05-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz L, Zhang QG, Zhou CF, Han D, Gulati P, Yang LC, et al. Role of Rac1 GTPase in NADPH oxidase activation and cognitive impairment following cerebral ischemia in the rat. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murikinati S, Jüttler E, Keinert T, Ridder DA, Muhammad S, Waibler Z, et al. Activation of cannabinoid 2 receptors protects against cerebral ischemia by inhibiting neutrophil recruitment. FASEB J. 2010;24:788–798. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-141275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony DC, Walker K, Perry VH. The therapeutic potential of CXC chemokine blockade in acute inflammation in the brain. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 1999;8:363–371. doi: 10.1517/13543784.8.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brait VH, Rivera J, Broughton BR, Lee S, Drummond GR, Sobey CG. Chemokine-related gene expression in the brain following ischemic stroke: no role for CXCR2 in outcome. Brain Res. 2011;1372:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.