Abstract

It is well known that many of the actions of estrogens in the central nervous system are mediated via intracellular receptor/transcription factors that interact with steroid response elements on target genes. However, there now exists compelling evidence for membrane estrogen receptors in hypothalamic and other brain neurons. But, it is not well understood how estrogens signal via membrane receptors, and how these signals impact not only membrane excitability but also gene transcription in neurons. Indeed, it has been known for sometime that estrogens can rapidly alter neuronal activity within seconds, indicating that some cellular effects can occur via membrane delimited events. In addition, estrogens can affect second messenger systems including calcium mobilization and a plethora of kinases to alter cell signaling. Therefore, this review will consider our current knowledge of rapid membrane-initiated and intracellular signaling by estrogens in the hypothalamus, the nature of receptors involved and how they contribute to homeostatic functions.

Keywords: ERα, ERβ, GABAB receptor, Gαq-mER, GIRK channels, GnRH, μ-opioid receptor, PKA, PKC, POMC

I. CLASSICAL ESTROGEN RECEPTORS AND 17β-ESTRADIOL (E2) BINDING SITES

ERα and ERβ

Studies utilizing 3H-17β-estradiol to explore binding sites in the brain revealed that estradiol-concentrating neurons are localized in hypothalamic regions including the preoptic (POA), periventricular (PV) and arcuate nuclei [154,177,179,204,217]. Since these initial autoradiography studies, two different estrogen receptors (transcription factors), ERα and ERβ, have been cloned and their distribution thoroughly elucidated using in situ hybridization and/or immunocytochemistry [48,71,78,116,117,119,148,178,181,182,184]. ERα is robustly expressed in regions such as the preoptic area (POA), bed nucleus stria terminalis (BNST), amygdala, periventricular nucleus (PV), ventrolateral part of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH) and the arcuate nucleus. ERβ is found in many of the same regions, but is more highly expressed in the BNST, POA, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) and supraoptic nuclei (SON), with some variation across species [116,119,137,181,218]. ERα and ERβ are also found in other brain regions including the cortex, hippocampus, midbrain, striatum, diagonal band of Broca and basal nucleus of Meynert [133,181]. Co-localization studies have identified ERα in neurons containing GABA, neurotensin, somatostatin, galanin, dopamine, norepinehprine, NPY, proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and kisspeptin [60,84,87,90,95,119,124,171,190]. For the most part, ERβ is expressed in different populations of neurons such as those containing gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH), vasopressin (VP), oxytocin (OT), and nociceptin/orphanin FQ, as well as in midbrain serotonin neurons [25,79,86,91–94,97,101,191]. In addition, ERα and ERβ are both localized in neurons expressing corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), as well as in subpopulations of unidentified hypothalamic neurons [7,25,71,183].

Selective membrane binding sites for E2 were first identified on endometrial cells [155,156], and later studies revealed relatively high affinity, specific binding of [3H]-17β-estradiol to synaptosomal membranes prepared from the adult rat brain [213]. The CNS findings were later corroborated using the membrane impermeant 17β-estradiol-6-[125I]-conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA) [233]. Furthermore, competition-binding assays of synaptosomal membranes showed that the hypothalamus exhibited a relatively high affinity (3 nM) binding site for E2 and somewhat lower affinity binding sites in the olfactory bulb and cerebellum [166,167]. The stereospecificity of the binding was demonstrated by displacement of the radiolabeled E2 with cold E2 or E2-BSA, but not by 17α-estradiol or 17α-estradiol-BSA even at micromolar concentrations [167]. These biochemical data complemented earlier electrophysiological findings that gonadal steroid signaling could rapidly be initiated at the membrane (see below) [102–106,109].

II. ESTROGEN SIGNALING

Nuclear-Initiated Signaling of Estrogen

Estrogen receptors regulate cellular function through at least two signaling pathways previously broadly classified as “genomic” and “nongenomic” [12,130]. However, the FASEB Steroid Signaling working group suggested that “membrane-initiated steroid signaling” and “nuclear-initiated steroid signaling” are more appropriate terminologies [81]. The nuclear-initiated signaling of estrogen via ERα and ERβ exert diverse effects on a variety of tissues that involves gene stimulation as well as gene repression [38,54,85,112,145,198]. In general, this “classical” signaling pathway of estrogen involves steroid-dependent formation of nuclear estrogen receptor homo- or heterodimers and the subsequent binding of this complex with a unique DNA sequence known as an estrogen response element (ERE), in E2-responsive gene promoters [73,140,147]. The inactive ER exists in a complex of several proteins that disassociate upon ligand binding, which transforms the receptor to an active state [38,73]. More specifically, recruitment of other nuclear co-activator and co-regulatory proteins and interactions with the transcription machinery results in transactivation of genes that contain EREs [73,140].

Several genes in the brain that are clearly estrogen-responsive do not appear to contain ERE sequences [73,127]. There is compelling evidence that ERα and ERβ can regulate transcription of some of these “estrogen-responsive” genes by interacting with other DNA-bound transcription factors, such as specificity protein-1 (SP-1) and activator protein 1 (AP-1), rather than binding directly to DNA [73,99,151]. For example, the ligand-induced responses with ERβ, in contrast to ERα, at an AP-1 site illustrate the negative transcriptional regulation by estrogens and strong positive regulation by ER antagonists like ICI 164,384 [151].In addition, Kiss1 mRNA is differentially regulated by E2 in the anteroventral periventricular (AVPV) nucleus and arcuate nucleus; and although the positive E2 regulation of Kiss1 mRNA expression in the AVPV is dependent on an ERE-binding site the down regulation of Kiss1 mRNA in the arcuate nucleus is via an ERE-independent mechanism [70]. Therefore, there are potentially multiple mechanisms for differential regulation of gene expression by E2 via nuclear-initiated signaling. Using suppression subtraction hybridization, we have identified a number of high as well as low abundant estradiol-regulated genes in the guinea pig arcuate nucleus [127]. Generating a guinea pig specific microarray of these genes, allowed us to compare the effects of E2 and STX, a selective ligand for a membrane estrogen receptor (see below).

Membrane-initiated signaling of E2

It has been known for a number of years that E2 has acute, membrane-initiated signaling actions in the brain [108,134,174]. A decade ago the nature and physiological significance of these actions were a matter of debate, but it is now widely accepted that some of the actions of E2 are quite rapid and cannot be attributed to the classical nuclear-initiated steroid signaling of ERα or ERβ. Importantly, ERα and ERβ can associate with signaling complexes in the plasma membrane [15,20,46,153,169,201]. In addition, many of the rapid effects of E2 can be induced by selective ERα or ERβ ligands, antagonized by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 and are absent in animals bearing mutations in ERα and/or ERβ genes [2,19,20,38,49,188,214]. However, it is also evident that E2 can activate bona fide G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), the most notable GPR30 and a Gαq-coupled membrane ER [75,110,146,160,161,211,212,231].

Substantial evidence has been generated in the support of a novel Gαq-coupled membrane ER (Gαq-mER). Intracellular sharp electrode and whole cell patch recording from guinea pig and mouse hypothalamic slices have been used to characterize this Gαq-mER [121,160,161]. Electrophysiological studies are one of the most direct methods for establishing membrane-initiated signaling. These hypothalamic slice studies established that E2 acts rapidly and stereospecifically within physiologically-relevant concentrations (EC50 = 7.5 nM) to significantly reduce the potency of μ-opioid and GABAB agonists (i.e., desensitize) to activate an inwardly rectifying K+ conductance [121,160]. Estrogenic desensitization of μ-opioid and GABAB receptors is mimicked either by stimulation of adenylyl cyclase with forskolin or by direct protein kinase A (PKA) activation with the non-hydrolyzable cAMP analog Sp-cAMP, in a concentration-dependent manner [121,160]. Furthermore, the selective PKA antagonists KT5720 and Rp-cAMP block the effects of E2. As one would predict from the literature on densitization of GPCRs [67], PKA is downstream in a signaling cascade that is initiated by a Gαq-coupled membrane ER that is linked to activation of phospholipase C (PLC)-protein kinase C (PKC)-PKA [160,161]. Importanly, E2 does not alter the affinity of the μ-opioid and GABAB ligands for their respective receptors [40]. Furthermore, the ER antagonists ICI 164,384 and ICI 182,780 block the actions of E2 with subnanomolar affinity (Ki = 0.5 nA) that is similar to Ki for antagonism of ERα [121,221]. These pharmacological findings clearly argue for a novel G-protein-coupled membrane receptor with high selectivity for E2 (Fig. 1).

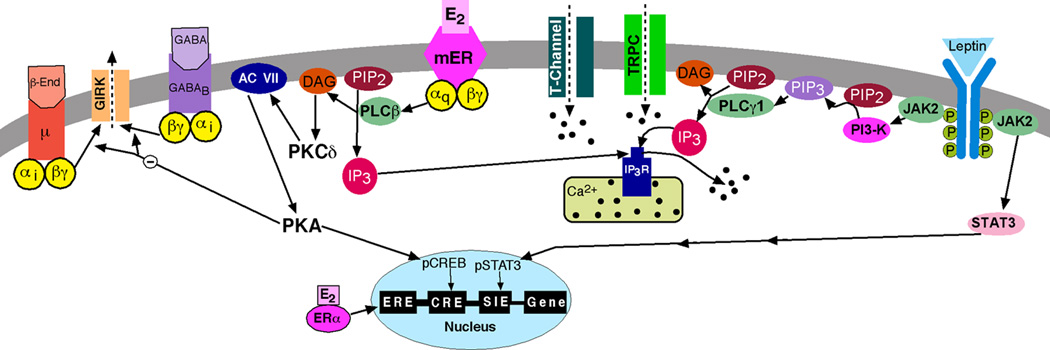

Figure 1. Cellular actions of 17β-estradiol (E2) and leptin in POMC neurons.

Schematic overview of the E2-mediated modulation of Gαi,o-coupled (μ-opioid and GABAB) receptors via a membrane-associated receptor (mER) in hypothalamic POMC neurons. E2 binds to a mER that is Gαq –coupled to activate phospholipase C and catalyzes the hydrolysis of membrane-bound phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) to inositol 1,4,5 triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). Calcium is released from intracellular stores (endoplasmic reticulum) by IP3, and DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC). Through phosphorylation, adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity is upregulated by PKC. The generation of cAMP activates PKA, which can uncouple μ-opioid (μ) and GABAB receptors from their signaling pathway through phosphorylation of a downstream effector molecule (e.g., G protein-coupled, inwardly rectifying K+, GIRK, channels). PKA can also potentially phosphorylate other channels (e.g., TRPC channels) to alter their function (not shown). In addition, the membrane-initiated E2 signaling through PKA can phosphorylate cAMP-responsive element binding protein (pCREB), which can alter gene transcription through its interaction with the cAMP responsive element (CRE). Therefore, the rapid membrane-initiated signaling can alter gene expression in an estrogen-response element-independent fashion. Leptin binds to its receptor (LRb) to activate Jak2, which phosphorylates IRS proteins and in turn activates PI3 kinase (PI3-K). PI3 kinase subsequently activates PLCγ1 to augment TRPC channel activity. All of these signaling events initiated by E2 and leptin enhance POMC neuronal excitability.

In view of the differences between circulating levels of E2 and working concentrations of E2 used for in vitro analysis, it is important to clarify the pharmacological analysis of in vitro E2 physiological responses: When applying E2 in a bath superfusing hypothalamic slices, the physiological actions depend on the pharmacokinetics of E2 in the slice as it does for all other tissues. Therefore, it is important to do a dose-response to establish the potency and efficacy of E2. The potency (EC50) of an agonist is the concentration required to produce fifty percent of the maximum effect in an experimental preparation. The value is obtained from a mathematical curve fitted to experimental data points. The potency (EC50) is dependent on the binding affinity, the efficacy of agonist, the receptor reserve in the tissue or cell, and the ability of the agonist (i.e., E2) to penetrate to the site of action [66]. As discussed above, the EC50 value for E2 to rapidly attenuate (desensitize) the μ-opioid response is 7.5 nM [121], whereas the EC50 for E2 to augment the KATP channel activity in in GnRH neurons is an order of magnitude lower (0.6 nM), which is probably reflective of the receptor reserve in GnRH neurons versus POMC neurons [231]. Most importantly, the sin quo non for establishing a specific receptor-mediated response is the blockade by a selective antagonist. Indeed, the selective ER antagonists ICI 164,384 and ICI 182,780 block the actions of E2 in POMC neurons and GnRH neurons with subnanomolar affinity (Ki = 0.5 nM), which is similar to Ki for inhibition of E2 binding to ERα [121,221]. Therefore, based on all of the criteria for establishing a physiological response, these rapid actions of E2 are physiological. The importance of this rapid response is discussed in physiological contexts below.

About a decade ago a diphenylacrylamide compound, STX, that does not bind ERα or ERβ [160,161] was developed to selectively target the Gαq-mER and its downstream signaling cascade--phospholipase Cβ-protein kinase Cδ-protein kinase A pathway--that mediates μ-opioid and GABAB desensitization in hypothalamic neurons (Fig. 1). The design arose out of studies in which we found that E2 stereospecifically (17α-estradiol is not active) activates the Gαq-mER signaling pathway (see above), and these actions were blocked by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 [121,160,161]. The results from these physiological and pharmacological experiments led to the design of STX, which is structurally similar to 4-OH tamoxifen, to target the Gαq-mER signaling pathway [160]. As predicted, STX had greater affinity (~20-fold) for the Gαq-mER than E2 and does not bind to ERα or ERβ [161,210]. Most importantly, both STX and E2 activated this Gαq signaling pathway in mice lacking both ERα and ERβ and in GPR30-knockout mice [161,163]. Definitive characterization (i.e., cloning ) of this novel Gαq-mER is currently a work in progress.

Parallel studies initiated in hippocampal slices some twenty years ago showed that E2 enhanced N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-mediated excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) and long-term potentiation (LTP) following Schaffer (collateral) fiber stimulation [61,175,224]. Also, E2 potentiated non-NMDA (kainate)-mediated excitation of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons via activation of a cAMP/PKA pathway [76,77]. Importantly, these rapid actions of E2 on glutamate excitation of hippocampal neurons were still present in animals deficient in ERα (from Dr. Ken Korach, NIH), suggesting a novel mechanism (receptor) for the rapid actions of E2 in the hippocampus [75]. In addition E2 and E2-BSA applied acutely to the hippocampus in ovariectomized animals produced a sustained reduction of the slow afterhyperpolarization current (IAHP) in CA1 pyramidal neurons, which is mediated by a Ca2+ - activated K+ conductance [26]. This provided further evidence for the involvement of a membrane ER, although the mechanism by which E2 regulates Ca2+ influx into CA1 neurons is currently unknown. More recent studies from the Woolley lab have shown that E2 via ERβ has presynaptic effects to enhance glutamate release (increased vesicle release probability) and hence excitation of CA1 neurons [192]. In addition, E2 via ERα association with metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) supresses GABA-A mediated inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) [96]. The ERα mediated effects are via mGluR1-dependent mobilization of the endocannabinoid anandamide that retrogradely suppresses GABA from presynaptic boutons. Interestingly, this only occurs in females and not males, which is reminiscent of the findings from the Boulware et al. [19,20] who showed in female and not male hippocampal CA3-CA1 neuronal cultures that E2 rapidly stimulates MAPK-dependent cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation. This modulation of CREB activity also occurs via ERα interactions with mGluR 1. The protein-protein interaction between the “classical” ERs and mGluRs has not been fully elucidated, but ERα and GluR1a have been co-immunoprecipitated in membrane fractions from both astrocytes and neurons [46,47,118]. This interaction is discussed further below.

Recently, the orphan GPCR GPR 30 has received notoriety because of its role in mediating E2’s effects in the CNS [110,123,146]. GPR30 exhibits the signaling characteristics of a bonafide ER [158,208]. In breast cancer cells that are transfected with GPR30, E2 activates the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), ERK1 and ERK2, and these actions are independent of ERα or ERβ [56,59]. Accordingly, E2 activates Gβγ-subunits that promote the release and activation of an epidermal growth factor precursor (proHB-EGF). The active HB-EGF binds to the EGF receptor (ErbB) to facilitate receptor dimerization and downstream activation of ERK [56–58]. Interestingly, the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) tamoxifen and ER antagonist ICI 182,780 both promote GPR30-dependent transactivation of the EGF receptor and subsequent MAPK activation. It is important to note that the Gαq-mER-mediated response to E2 in arcuate neurons is still present in GPR30 KO mice [163]. GPR30 has been localized in the brain and E2 binds to this receptor [14,21,65,157], and recent studies from the Terasawa lab have shown that GPR30 is involved in mediating the rapid actions of E2 in monkey placode GnRH neurons (see below). Therefore, it is evident that estrogen can rapidly alter cell function through ERα, ERβ and/or novel GPCRs that bind E2.

III. CONSEQUENCES OF E2 MEMBRANE SIGNALING IN HYPOTHALAMUS

E2 Signaling in GnRH Neurons

Despite having been studied extensively for over 30 years, the mechanisms by which estrogens regulate gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons is not well understood. It has been obvious for a number of years that GnRH neurons are modulated by E2 in a complex manner. For example, loss of estrogens by ovariectomy disrupts GnRH regulation of pituitary LH secretion and results in elevated levels of plasma LH. This effect is due to the loss of negative feedback actions of E2. However, both negative and positive (induction of the LH surge) feedback regulation of LH (and GnRH) secretion can be restored by replacement with E2 [17,24,28,125,138]. The positive feedback is believed to be by an action of E2 in the AVPV nucleus at least in rodents [82,85,195]. In fact, ERα has been localized to AVPV neurons, and knockout of the receptor in forebrain neurons including AVPV neurons abrogates the positive feedback effects of E2 on GnRH neurons [223]. Neurons in the AVPV and adjacent periventricular areas express kisspeptin, a neuropeptide encoded by the Kiss1 gene, and GABA, both of which are important for regulation of GnRH neurosecretion [29,44,98,126,195,215]. Although the AVPV neurons express high levels of ERα (and also ERβ), and the actions of E2 are mediated, in part, via nuclear-initiated signaling mechanism (Smith et al 2005) [181,194,195], AVPV neurons are also sensitive to the rapid actions of E2. For example, E2 within 30 min increases the expression of pCREB in AVPV neurons [74]. At the cellular level, individual AVPV neurons that co-localize GABA respond to both β-adrenergic and α-adrenergic input by a reduction in the medium afterhyperpolarization current (mIAHP), which increases the action potential firing in these neurons [216]. Moreover, the α1-adrenergic, but not β-adrenergic inhibition of the mIAHP is potentiated after acute (15–20 min) exposure to E2, which further increases neuronal excitability [216]. The E2 enhancement of the α1-adrenergic receptor-mediated inhibition of small conductance, calcium-activated K+ (SK) channels (underlying the IAHP) is initiated within 15 min in vitro and lasts for at least 24 h following systemic steroid administration, suggesting both rapid and sustained effects [216]. Since SK channels are critical for modulating neuronal firing rate and pattern [176,197], estrogen-induced modulation of these channels would have significant functional consequences for AVPV neurons and their downstream target GnRH neurons.

In terms of negative feedback by E2, the relatively quick inhibition of GnRH and LH secretion (~15 min) [35,111] is congruent with a membrane initiated signaling of E2. In fact years ago, we showed that guinea pig GnRH neurons are rapidly hyperpolarized by E2 via activation of an inwardly-rectifying (G protein-coupled) K+ (GIRK) conductance in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX), which blocks fast Na+ channel activity and essentially “electrically isolates” GnRH neurons from synaptic inputs [36,109,120]. In GT1-7 cells, an immortalized GnRH neuronal cell line, E2 inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity and cAMP production via a pertussis toxin-sensitive (Gαi,o coupling) mechanism [144]. In mice, physiological concentrations (picomolar) of E2 rapidly augments KATP channel (also of the inwardly rectifying family) activity to hyperpolarize GnRH neurons. E2 activates a PKC-PKA signaling pathway and hence the selective Gαq-mER ligand STX is also able to mimic the effects of E2 [231]. Both the effects of E2 and STX are abrogated by ICI with a Ki of 0.5 nM [121] (Zhang et al. unpublished observations).

The membrane initiated “negative feedback” effects of E2 on GnRH neurons is important for recruiting the critical channels that underlie burst firing behavior [107]. Moreover after providing an initial hyperpolarizing stimulus, G protein-coupled responses can be rapidly inhibited to allow the excitatory inputs (e.g., kisspeptin) and intrinsic conductances to take over and generate burst firing in GnRH neurons. More specifically, K+ (Kir) channel-mediated hyperpolarization is potentially involved in recruitment of excitatory channels that are critical for burst firing of GnRH neurons, including T-type calcium channels that are highly up-regulated by both membrane-initiated and nuclear-mediated E2 signaling in GnRH neurons [16,230]. In addition, nanomolar concentrations of E2 enhance action potential firing by modulating intrinsic afterhyperpolarizing and afterdepolarizing potentials via a PKA-dependent mechanism involving ERβ [30]. Picomolar concentrations of E2 also inhibit action potential firing via presynaptic ERα-dependent mechanisms [30]. Also, E2 via ERβ and/or GRP30 rapidly potentiates high-voltage-activated Ca2+ currents (L- and R-type Ca2+ channels) suggesting that Ca2+ signaling is also a target for E2 membrane actions in GnRH neurons [199]. Overall, the membrane-initiated E2 signaling plays a critical role in sculpting GnRH burst firing activity.

In primate and mouse olfactory placode GnRH (immature) neurons, E2 modulates Ca2+ oscillations, which synchronize with a periodicity of approximately 60 minutes [205–207], a rhythm which is similar to the pulsatile GnRH release [68,125]. Furthermore, nanomolar concentrations of a membrane-delimited E2 (E2-dendrimer, EDC) alter the patterns of Ca2+ oscillations in primate GnRH neurons [1]. The E2 membrane signaling modulation of Ca2+ oscillations in primate GnRH neurons is suppressed by pertussis toxin (PTX) treatment, attenuated by knockdown of GPR30 mRNA and partially mimicked by the GPR30 agonist G1 [146]. In addition, Terasawa and colleagues have found that a Gαq-coupled mER is also involved based on the findings that STX increases calcium oscillations and GnRH release from monkey placode neurons [110,146].

In the mouse, E2-induced Ca2+ oscillations are preserved in TTX-treated immature GnRH neurons, mimicked by E2-BSA and blocked by both PTX and by ICI 182,780 [205,206]. This would suggest that a direct G protein-associated (Gαi,o) ER is present in these immature GnRH neurons. The response is also present in 21 division GnRH neurons, which express essentially no ERβ, and therefore, ERβ may not be the ER mediating E2’s actions [206]. In addition, in adult mouse GnRH neurons, nanomolar concentrations of E2 increase Ca2+ transients via presumably presynaptic GABA input in an ERα-dependent manner [173]. These E2-mediated effects on Ca2+ oscillations are maintained in ERβKO mice [173]. However, E2 activation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in mouse GnRH neurons is present in ERαKO mice, but absent in ERβKO mice [2]. Collectively, these findings indicate that there are multiple membrane-initiated (acute) actions of E2 in GnRH neurons, some of which are directly on GnRH neurons and involve ERβ but also GPR30 and a Gq-coupled mER. Other acute actions of E2 are presynaptic and involve ERα as well as other ERs.

Although E2 membrane signaling may be involved in negative feedback, it has been difficult to incorporate ERβ-, GPR30- and/or Gαq-mER-dependent signaling into a physiological context of E2 positive feedback when either global or neuronal-specific ERα knockdown in mice apparently abrogates positive feedback and the LH surge in mice [223]. These findings suggest that the estrous cycle in lower mammals only requires ERα-mediated E2 actions in neurons. However, these gene deletion experiments do not necessarily mean that only ERα signaling is involved. Clearly ERα is a transcription factor that affects hundreds of genes important for cell signaling – i.e., some of these genes may be essential for a mER-initiated response that normally contributes to female reproduction but is defective in ERαKO mice [88,127].

E2 Membrane Signaling and Reproductive Behavior

Traditionally nuclear-initiated E2 signaling was considered sufficient for female sexual receptivity - lordosis in rodents. This behavior, characterized by the ventral arching of the spine in response to mounting by a male, is displayed during behavioral estrus and is controlled by E2 through a complex hypothalamic circuitry involving the arcuate nucleus, medial preoptic nucleus (MPN) and the VMH [13,134]. Within the past decade, it has become clear that in addition to the direct nuclear actions of E2 in these various hypothalamic sub-regions, membrane-initiated signaling is important for sexual behavior. An important discovery was that an initial E2 membrane signaling activates both PKC and PKA signaling cascades in VMH neurons that augments the nuclear-mediated E2 signaling and lordosis behavior [114]. The interaction between E2 membrane-initiated and nuclear-initiated signaling is being further discussed below.

Another proposed mechanism of E2 membrane-initiated signaling involved in lordosis behavior is based on data indicating that classical ERα at the cell membrane transactivates mGluR1a to initiate cell signaling [20,46,135]. This ERα-mGluR1a interaction regulates the hypothalamic circuitry controlling female sexual receptivity [46]. ERα and mGluR1a are co-expressed in arcuate cells and can be co-immunoprecipitated from membrane fractions [46,47,118]. Blocking either ERs or mGluR1a in the arcuate nucleus prevents the rapid PKC phosphorylation and activation of MPN projecting proopiomelanocortin (POMC, the precursor of β-endorphin) neurons that are responsible for activating/internalizing μ-opioid receptors [50,136,186]. Similarly, activation of arcuate neurons with a membrane-impermeant E2 or mGluR1a agonist (DHPG, (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine) stimulates μ-opioid receptor internalization [46]. These MPN μ-opioid receptor neurons, in turn, project to the VMH, and the transient activation of μ-opioid receptors is necessary for full sexual receptivity that is apparent 30–48 hrs after E2 treatment [187]. While full sexual receptivity also requires E2-induced gene transcription, one question about membrane-initiated E2 action is how the transient, E2-induced activation and internalization of μ-opioid receptors in the MPN facilitate full sexual receptivity at the later time points? One possible explanation is that μ-opioid receptor activation produces a transient inhibition of the MPN neurons that project to the VMH. These neurons rebound from a hyperpolarized state (as we describe above for GnRH neurons) with facilitated firing that excites VMH neurons, ultimately facilitating sexual receptivity.

E2 Signaling in Energy and Temperature Homeostasis

Besides its obvious role in the feedback control of the reproductive axis, E2 modulates a number of hypothalamic-regulated autonomic functions, most notably energy homeostasis and temperature. E2 signaling via ERα is a necessary component of the regulation of energy homeostasis [69]. In rodents, hypo-estrogenic states are clearly associated with decreased activity and an increase in body weight [6,23,32,33,41,42,100,129,161]. In humans, a loss-of-function mutation in ERα has a clear metabolic phenotype in man with expression of type 2 diabetes, hyperinsulinemia and obesity [193]. However, global reinstatement of an ERα that is lacking the ERE targeting domain is sufficient for “rescuing” the metabolic deficits in mice [152]. These findings suggest an important role for non-ERE mediated E2 signaling. Moreover, brain-specific knockout of ERα causes hyperphagia and hypometabolism [141,226], and selective knockdown of ERα in POMC neurons recapitulates the hyperphagic phenotype in female mice [226]. However, there are at least two caveats that impact the interpretation of gene deletion experiments. Firstly, ERα is a transcription factor affecting the expression of hundreds of genes important for cell signaling, and many of these genes are essential for mER initiated responses that contribute to POMC excitability and hence control of energy homeostasis [88,127]. Secondly, POMC-Cre (mice utilized in [226]) is also expressed in progenitor neurons that are destined to become NPY and perhaps other hypothalamic and extrahypothlalamic neurons [149,150]. Therefore, ERα knockout spreads well beyond the single neuron phenotype as originally thought. Hence, one must be cautious in interpreting ERα knockout (global or targeted) experiments.

Experiments dating back to 30–40 years ago determined that the anorectic effects of E2 in rodents are mediated through CNS sites of action since direct injections of E2 into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) or arcuate/ventromedial nucleus are effective to reduce food intake, body weight and increase wheel running activity in females [4,23,34]. More recent experiments have shown that E2 up-regulates the expression of the peptide β-endorphin in POMC neurons in ovariectomized female guinea pigs [9,209]. Furthermore, there is a decrease in hypothalamic β-endorphin levels in the hypothalamus that correlates with weight gain in postmenopausal women who do not take hormone therapy [122]. In contrast, E2 reverses the ovariectomy-induced increase in arcuate NPY mRNA expression in rodents [180]. Therefore, it appears that the arcuate nucleus and specifically POMC neurons are major targets for the anorectic actions of estrogen, which underscores their importance in the control of energy homeostasis. In addition, POMC neurons are critical for the regulation of feeding behavior and are also involved in the rewarding aspects of food intake [5,83].

The ability of STX to robustly mimic the effects of E2 on POMC neuronal activity led to the hypothesis that the Gαq-mER may have a role in the control of energy homeostasis. Indeed, in translational animal experiments we have demonstrated that peripheral administration of STX mimics the effects of E2 in controlling energy homeostasis (Fig. 2) [161,170,172]. As predicted from the E2- and STX-induced increase in POMC neuronal activity, both E2 and STX reduce food intake and, subsequently, the post-ovariectomy body weight gain. STX and E2 inhibit food intake in ovariectomized guinea pigs by reducing meal frequency, and there is a subsequent reduction in abdominal fat accumulation [170]. Furthermore, treatment with STX, similar to E2, induces new gene transcription in the arcuate nucleus [172]. Many of the STX-regulated genes in the arcuate nucleus are involved in the control of neuronal excitability (e.g., Cav3.1) and intracellular signaling in POMC neurons [172] (Fig. 3). For example, the phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3) kinase regulatory subunits are regulated by E2 and STX: PI3 kinase p55γ mRNA is increased by E2 treatment [128] and PI3 kinase p85α mRNA is upregulated by STX [172] (Fig. 3). Therefore, Gαq-mER appears to function in the estrogenic control of energy homeostasis through activation of POMC neurons in the arcuate nucleus, although other hypothalamic neurons are involved via synaptic input from POMC neurons and/or via direct actions of E2.

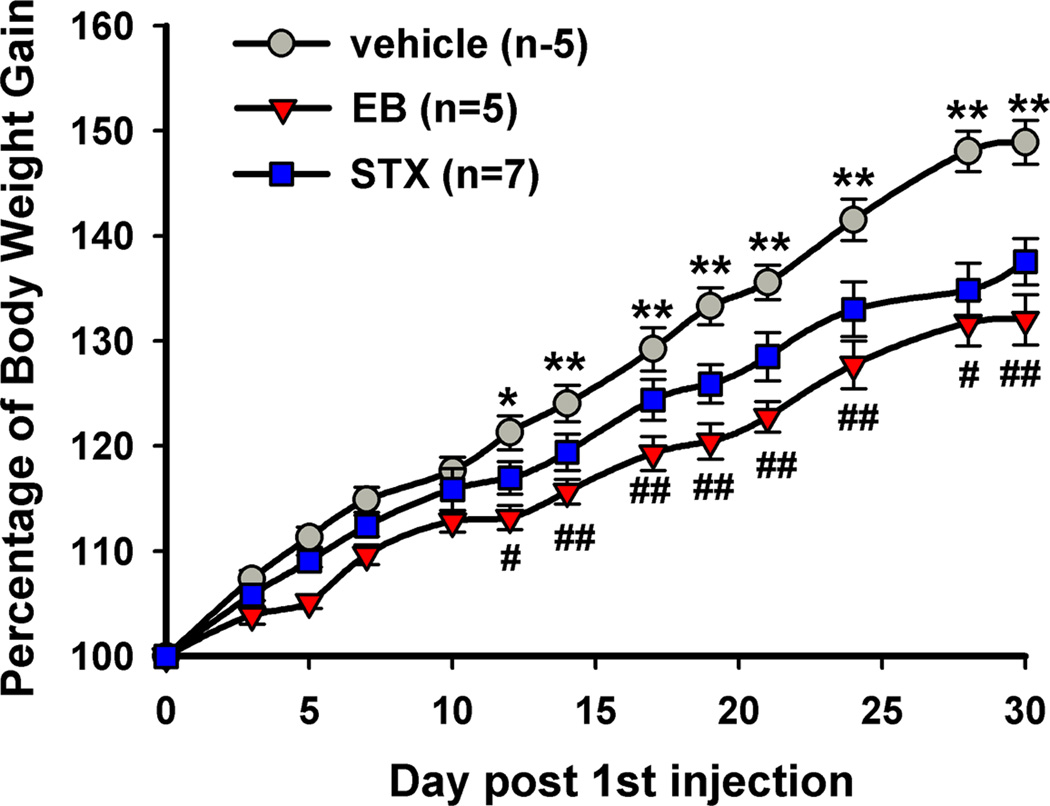

Figure 2. 17β-Estradiol and STX attenuate the body weight gain in female guinea pigs after ovariectomy.

Female guinea pigs were ovariectomized and after a one-week recovery period were given bi-daily subcutaneous injections of vehicle, 17β-estradiol benzoate (EB), or STX starting on day 0. A two-way ANOVA (repeated measures) revealed an overall significant effect of both EB and STX (p<0.001), and post hoc Newman-Keuls analysis revealed daily significant differences between EB and vehicle-treated, and STX and oil-treated groups (** p< 0.01). (Reproduced from Roepke et al. Endocrinology 149: 6113–24, 2008, with permission from the Endocrine Society)

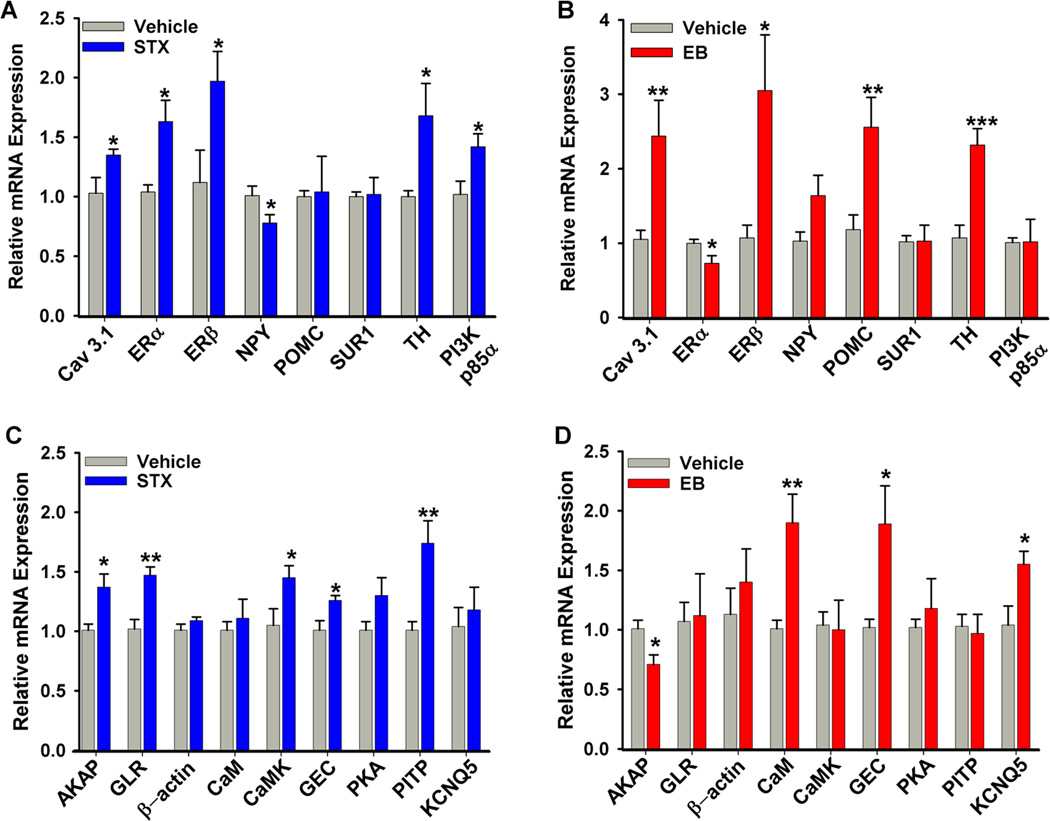

Figure 3. Genes regulated by E2 and STX in guinea pig arcuate nucleus.

Quantitative real-time PCR confirmed regulation of multiple genes by STX in the arcuate nucleus [172]. The relative mRNA expression for selected control genes (A, B) and selected genes of interest (C, D) from microdissected arcuate tissue from vehicle-treated (PPG (n-5) or oil (n=7)) females and STX- (n=7) or EB-treated (n=6) females. The expression values were calculated using the CT method where the calibrator was the average CT of the vehicle-treated samples. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. Statistics: two-tailed Student’s t-test (p<0.05*; p<0.01**; p<0.001*** compared to vehicle). AKAP11, A-kinase anchoring protein 11; CaM-1, calmodulin 1; CaMKIIα, calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II αsubunit; Cav3.1, T-type calcium channel 3.1 subunit; ERα, estrogen receptor α; ERβ, estrogen receptor β; GEC-1, GABA-A receptor associated protein-like 1; GLR, Glycine Receptor β; KCNQ5, M-current potassium channel subunit 5; NPY, neuropeptide Y; PI3K p85, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, p85α subunit; PKAα1, protein kinase A α1 subunit; PITP, phosphatidylinositol transfer protein β; POMC, pro-opiomelanocortin; SUR1, sulfonylurea receptor 1; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase. (Reproduced from Roepke et al. Endocrinology 149: 6113–24, 2008, with permission from the Endocrine Society)

Another critical homeostatic function modulated by circulating estrogens is the maintenance of core body temperature (Tc). In fact, hot flashes affect 75–85% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women [139]. Hot flashes are characterized by periods of sweating and peripheral vasodilation and are often associated with increased environmental temperature [168]. Therefore, a hot flash can be defined as an exaggerated heat dissipation response initiated by the preoptic temperature sensitive neurons. Although the mechanism behind this response is not known, repeated observations have found that the majority of hot flashes are preceded by elevation in Tc independent of peripheral vasoconstriction or elevated metabolic rate [62,64]. Therefore, it has been postulated that elevated Tc may serve as one trigger of menopausal hot flashes [63,168]. In general, there is compelling experimental evidence that the incidence of hot flashes in hypo-estrogenic females is decreased by E2 treatment [22,63,203]. The estrogenic reduction in the naloxone-induced rise in tail skin temperature of morphine-dependent ovariectomized rats has been the industry standard for a hot flash model [113,132,185]. The morphine-dependence, naloxone-precipitated withdrawal rat model has a number of drawbacks because of the adverse autonomic reactions independent of an elevation in core and skin temperature. But the model does highlight the involvement of CNS opioid effects (e.g., from POMC neurons) directly or indirectly on preoptic temperature sensitive neurons [229].

We have established a guinea pig “hot flash” model based on the hypothesis that the expression of vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women is due to the reduced thermo-neutral zone in core body temperature [62]. In the ovariectomized female guinea pig, both E2 and STX significantly reduce Tc compared to animals receiving vehicle injections (Fig. 4) [170]. The exact cellular target for E2 and specifically the Gαq-mER modulation of Tc has not been identified. However, one potential cellular mechanism is the direct action of E2 via the Gαq-mER on thermosensitive (GABAergic) neurons in the medial preoptic area of the hypothalamus [18,72,142]. Previous studies in ovariectomized female guinea pigs have shown that medial preoptic GABAergic neurons respond to acute E2 treatment via the Gαq-mER signaling pathway to attenuate GABAB inhibitory input, leading to increased GABA neuronal activity [215]. Moreover, activation of these medial preoptic GABA neurons are responsible for evoking the vasomotor responses in rodents [143] underlying heat dissipation responses (i.e., vasodilatation, sweating) seen in women experiencing hot flashes.

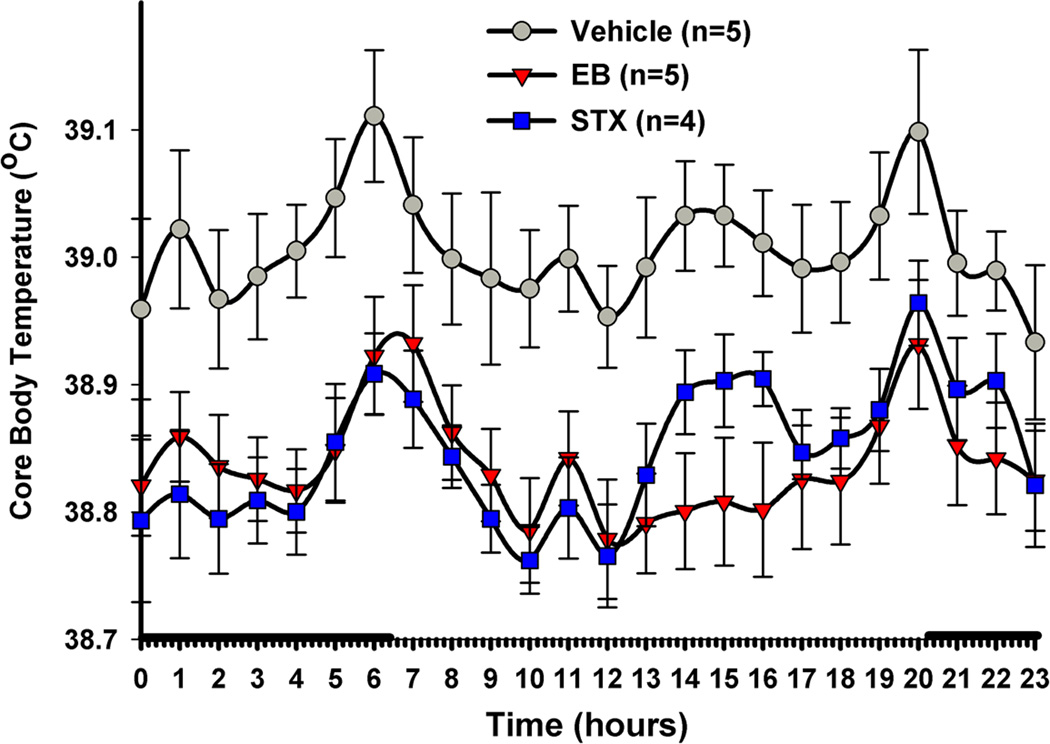

Figure 4. E2 and STX reduce core body temperature (Tc) of ovariectomized female guinea pigs.

Similar to 17β-estradiol benzoate (EB)-treated females (8 g/kg), the mER selective ligand STX (6 mg/kg) significantly decreased the Tc compared to the propylene glycol vehicle (PPG). Females were given daily injections of drug at 1000. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM for each hour of the day averaged over three weeks of temperature probe recordings. The data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA (p < 0.05, F = 4.787, df = 2) with post-hoc Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. All data points for both STX and EB were significantly different from vehicle (p<0.01) except for the STX 1400–1600 hr time points (p<0.05). The solid bars above the x-axis represent lights off or nighttime. (Reproduced from Roepke et al. Endocrinology 151: 4926–37, 2010, with permission from the Endocrine Society)

Importantly, the coupling of Gαq-mER to downstream signaling pathways is similar to the serotonin 5HT2A/2C receptors, which when activated, lower Tc and are implicated in thermoregulation dysfunction caused by ovariectomy [8,189]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors elevate endogenous serotonin levels and are therefore efficacious for treating hot flashes [196] and can significantly attenuate the effects of ovariectomy on thermoregulation in rodents [43]. Moreover, both the Gαq-mER and 5HT2C receptors attenuate inhibitory GABAergic signals in POMC neurons [164]. These similarities imply that serotonin via its Gαq-coupled receptor and E2 via Gαq-mER have similar cellular targets in the hypothalamic neurons that control Tc and energy homeostasis.

Recently, STX has been found to mimic the ability of E2 to maintain bone density in the ovariectomized female guinea pigs [170]. Although E2 has direct effects on the osteoclast/osteoblast cells involved in bone remodeling [53,200], E2 can reduce bone loss, a hallmark of hypo-estrogenic states, in part, by controlling the hypothalamic control of bone remodeling. It is known that the preautonomic paraventricular (PVN) neurons that drive sympathetic activity are involved in bone remodeling [202,227]. These PVN neurons receive a robust μ-opioid receptor inhibitory input, presumably from POMC neurons [225], and therefore, E2 via Gαq-mER can affect their excitability via inhibitory POMC input. Indeed, we have found that STX, like E2, preserves cancellous bone density, which supports potential role of this hypothalamic signaling pathway in maintanence of bone density (Fig. 5). However, STX, like E2, may also have peripheral effects (e.g., directly on osteoblasts) which cannot be ruled out at this time. Certainly, the decreased PVN output would dampen the sympathetic nervous system activity that controls bone remodeling via the adrenergic β2 receptor activity in the osteoblast cells [202]. In fact, there is an increase in bone formation and a decrease in bone reabsorption in adrenergic β2 receptor knockout mice [51]. Unlike in wild-type mice, gonadectomy of adrenergic β2 receptor knockout-mice does not alter bone mass or bone resorption parameters, indicating that increased sympathetic activity may be responsible for the bone loss in hypo-estrogenic states [51].

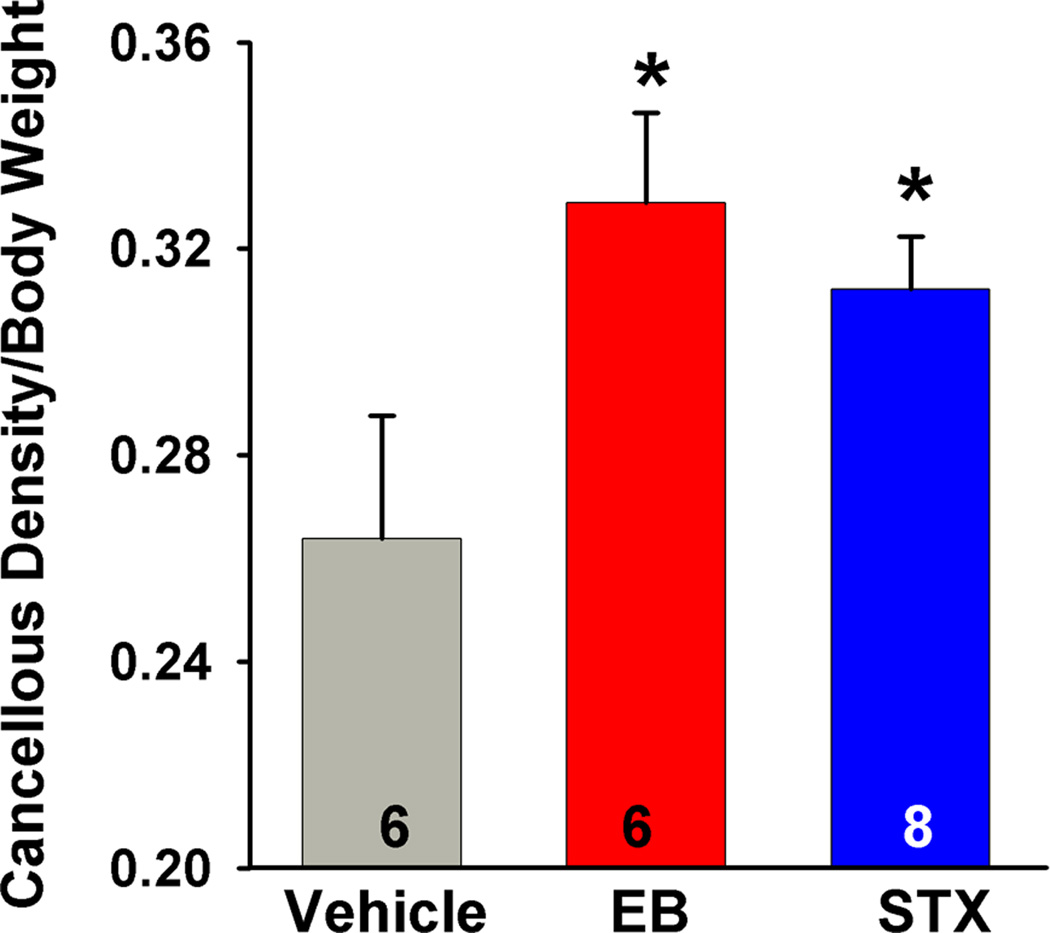

Figure 5. E2 and STX increase cancellous bone density of the proximal tibia in ovariectomized female guinea pigs.

Ovariectomized females treated with EB (20 µg/kg) or STX (12 mg/kg) for 52 days had significantly higher bone density in the proximal tibia compared to the vehicle-treated females. On day 52 the animals were killed, the tibia was harvested and the trabecular bone region was scanned using quantitative computer tomography [165]. A one-way ANOVA (p<0.05, F = 3.616, df = 2) followed by a post-hoc Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test (* = p<0.05) was used to compare significance between each treatment. (Reproduced from Roepke et al. Endocrinology 151: 4926–37, 2010, with permission from the Endocrine Society)

Cross talk between Gαq-mER and leptin receptor

The adipocyte hormone leptin binds to its long form receptor(LRb), which is expressed in a number of hypothalamic nuclei including the arcuate nucleus and in POMC and NPY neurons [52,80,131]. Genetic mutations in leptin or its receptor are associated with profound metabolic and physiological abnormalities such as obesity and infertility [55]. A rapid but vital action of leptin in acute suppression of food intake is to depolarize and augment firing in POMC neurons [39,89,162,222]. For a decade, the signaling cascade and the channels involved in the rapid excitation of POMC neurons was unknown. Recently however, it was discovered that leptin via its cognate receptor (LRb) activates janus kinase 2 (Jak2), which phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins and in turn activates PI3 kinase; PI3 kinase, subsequently activates PLCγ1 to open TRPC channels and depolarize POMC neurons (Fig. 1) [162]. Based on physiological, pharmacological and molecular biological (mRNA) profiling, TRPC1, 4, and 5 channels appear to be the key players in mediating the excitatory effects of leptin on POMC neurons [162]. Although these TRPC channels are known as “store operated calcium channels” [11,31], recent evidence indicates that the initial calcium signal in GnRH neurons comes via plasma membrane calcium channels that facilitate TRPC channel opening [37,115,232]. Since E2 and STX increase the expression of T-type calcium channel (CaV3.1) mRNA in the arcuate nucleus and this is associated with an increase in whole cell T-type calcium currents in POMC neurons (Qiu et al. unpublished findings) [159,172], we predict that TRPC channel activity can be augmented via E2-induced increase in the influx of Ca2+ through these channels (Fig. 1). In addition, both E2 and STX upregulate the expression of PI3 kinase regulatory subunits in the arcuate nucleus [128,172], which can augment the coupling of LRb to downstream signaling pathways that lead to the opening of these TRPC channels (Fig. 1). Therefore, it appears that E2 and leptin signaling are inextricably linked in POMC neurons to regulate energy homeostasis.

IV. SUMMARY

It is obvious from the plethora of studies using membrane-delimited E2 ligands and the mER selective ligand STX that “genomic” actions of E2 in the brain do not require the direct nuclear targeting of estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ). Signals that are initiated by E2 at the plasma membrane can trigger multiple intracellular signaling cascades including activation of MAPK, PI3K, and PKC pathways [10,27,45,219,228] that result in the phosphorylation of hundreds of proteins that ultimate can affect cell excitability and gene transcription (Fig. 1). E2 can bind to ERα, ERβ or the novel Gαq-mER to upregulate cAMP in hypothalamic neurons by increasing adenylyl cyclase activity [121]. Cyclic-AMP activates PKA, which in turn phosphorylates K+ channels to inhibit their activity or other (e.g., TRPC) channels to augment their activity, and in “one fell swoop” phosphorylates CREB to elicit new gene transcription [3,74,220,234]. Therefore, not only does membrane excitability change within a matter of seconds, but gene transcription can be activated within a relatively short time course in neurons independent of estrogen receptors interacting with EREs. Therefore, we need to continue to elucidate the cross talk of mER’s with other hormone and neurotransmitter signaling cascades in order to fully understand the role of E2 in modulating hypothalamic control of all homeostatic functions.

Highlights.

17β-estradiol and the mER selective ligand STX activate a Gαq-coupled membrane estrogen receptor in hypothalamic neurons.

17β-estradiol and STX increase calcium oscillations and GnRH release in monkey placode GnRH neurons.

17β-estradiol and STX modulate energy homeostasis.

17β-estradiol and STX lower core body temperature and increase bone density in hypo-estrogenic females.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank members of their laboratories who contributed to the work described herein, especially Drs. Yuan Fang, Anna Malyala, Jian Qiu, Troy A. Roepke and Chunguang Zhang and Ms. Martha A. Bosch. Also, special thanks to Ms. Martha A. Bosch for her skilled assistance with the illustrations and manuscript preparation. Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institutes Health grants NS 38809, NS 43330 and DK 68098. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe H, Keen KL, Terasawa E. Rapid action of estrogens on intracellular calcium oscillations in primate LHRH-1 neurons. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1155–1162. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham IM, Han SK, Todman MG, Korach KS, Herbison AE. Estrogen receptor beta mediates rapid estrogen actions on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5771–5777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahám IM, Todman MG, Korach KS, Herbison AE. Critical in vivo roles for classical estrogen receptors in rapid estrogen actions on intracellular signaling in mouse brain. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3055–3061. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahdieh HB, Wade GN. Effects of hysterectomy on sexual receptivity, food intake, running wheel activity, and hypothalamic estrogen and progestin receptors in rats. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1982;96:886–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appleyard SM, Hayward M, Young JI, Butler AA, Cone RD, Rubinstein M, Low MJ. A role for the Endogenous opioid beta-endorphin in energy homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1753–1760. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asarian L, Geary N. Cyclic estradiol treatment normalizes body weight and restores physiological patterns of spontaneous feeding and sexual receptivity in ovariectomized rats. Horm. Behav. 2002;42:461–471. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao A-M, Hestiantoro A, Van Someren EJW, Swaab DF, Zhou J-N. Colocalization of corticotropin-releasing hormone and oestrogen receptor-α in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in mood disorders. Brain. 2005;128:1301–1313. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berendsen HHG, Weekers AHJ, Kloosterboer HJ. Effect of tibolone and raloxifene on the tail temperature of oestrogen-deficient rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;419:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00966-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bethea CL, Hess DL, Widmann AA, Henningfeld JM. Effects of progesterone on prolactin, hypothalamic beta-endorphin, hypothalamic substance P, and midbrain serotonin in guinea pigs. Neuroendocrinol. 1995;61:695–703. doi: 10.1159/000126897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bi R, Foy MR, Vouimba RM, Thompson RF, Baudry M. Cyclic changes in estradiol regulate synaptic plasticity through the MAP kinase pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13391–13395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241507698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birnbaumer L. The TRPC class of ion channels: a critical review of their roles in slow, sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2009;49:395–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Björnström L, Sjöberg M. Mechanisms of estogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:833–842. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaustein JD, Erskine MS. Feminine sexual behavior: cellular integration of hormonal and afferent information in the rodent forebrain. In: Pfaff D, Etgen AM, Fahrbach SE, Rubin RT, editors. Hormones, Brain and Behavior. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 139–214. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bologa CG, Revankar CM, Young SM, Edwards BS, Arterburn JB, Kiselyov AS, Parker MA, Tkachenko SE, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER. Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nature Chem. Biol. 2006;2:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nchembio775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bondar G, Kuo J, Hamid N, Micevych P. Estradiol-induced estrogen receptor-α trafficking. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:15323–15330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2107-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosch MA, Hou J, Fang Y, Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK. 17β-estradiol regulation of the mRNA expression of T-type calcium channel subunits: role of estrogen receptor and estrogen receptor. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;512:347–358. doi: 10.1002/cne.21901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosch MA, Xue C, Ronnekleiv OK. Kisspeptin expression in guinea pig hypothalamus: Effects of 17β-estradiol. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012;520:2143–2162. doi: 10.1002/cne.23032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulant JA. Neuronal basis of Hammel's model for set-point thermoregulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006;100:1347–1354. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01064.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulware MI, Kordasiewicz H, Mermelstein PG. Caveolin proteins are essential for distinct effects of membrane estrogen receptors in neurons. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:9941–9950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1647-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulware MI, Weick JP, Becklund BR, Kuo SP, Groth RD, Mermelstein PG. Estradiol activates group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, leading to opposing influences on cAMP response element-binding protein. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5066–5078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brailoiu E, Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Mizuo K, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Dun NJ. Distribution and characterization of estrogen receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 in the rat central nervous system. J. Endocrinol. 2007;193:311–321. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks EM, Morgan AL, Pierzga JM, Wladkowski SL, O'Gorman JT, Derr JA, Kenney WL. Chronic hormone replacement therapy alters thermoregulatory and vasomotor fuction in postmenopausal women. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997;97:477–484. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.2.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butera PC, Czaja JA. Intracranial estradiol in ovariectomized guinea pigs: effects on ingestive behaviors and body weight. Brain Res. 1984;322:41–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caraty A, Locatelli A, Martin GB. Biphasic response in the secretion of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone in ovariectomized ewes injected with oestradiol. J. Endocrinol. 1989;123:375–382. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1230375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardona-Gomez GP, DonCarlos L, Garcia-Segura LM. Insulin-like growth factor I receptors and estrogen recetpros colocalize in female rat brain. Neurosci. 2000;99:751–760. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrer HF, Araque A, Buño W. Estradiol regulates the slow Ca2+ - activated K+ current in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:6338–6344. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06338.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cato ACB, Nestl A, Mink S. Rapid actions of steroid receptors in cellular signaling pathways. Science's STKE. 2002;2002:re9–re21. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.138.re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chappell PE, Levine JE. Stimulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone surges by estrogen. I. Role of hypothalamic progesterone receptors. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1477–1485. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.4.7428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christian CA, Moenter SM. Estradiol induces diurnal shifts in GABA transmission to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons to provide a neural signal for ovulation. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:1913–1921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4738-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu Z, Andrade J, Shupnik MA, Moenter SM. Differential regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activity and membrane properties by acutely applied estradiol: dependence on dose and estrogen receptor subtype. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:5616–5627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0352-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC. Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. Diabetes. 2006;55:978–987. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Zigman JM, Kemp CJ, Strader AD, Benoit SC, Woods SC, Mangiaracina M, Geary N. Estradiol-dependent decrease in the orexigenic potency of ghrelin in female rats. Diabetes. 2007;56:1051–1058. doi: 10.2337/db06-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colvin GB, Sawyer CH. Induction of running activity by intracerebral implants of estrogen in overiectomized rats. Neuroendocrinol. 1969;4:309–320. doi: 10.1159/000121762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Condon TP, Dykshoorn-Bosch MA, Kelly MJ. Episodic LH release in the ovariectomized guinea pig: Rapid inhibition by estrogen. Biol. Reprod. 1988;38:121–126. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod38.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Condon TP, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Estrogen modulation of the α1-adrenergic response of hypothalamic neurons. Neuroendocrinol. 1989;50:51–58. doi: 10.1159/000125201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Constantin S, Caligioni CS, Stojilkovic S, Wray S. Kisspeptin-10 facilitates a plasma membrane-driven calcium oscillator in gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neurons. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1400–1412. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr. Rev. 1999;20:358–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, Cerdán MG, Diano S, Horvath TL, Cone RD, Low MJ. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411:480–484. doi: 10.1038/35078085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunningham MJ, Fang Y, Selley DE, Kelly MJ. μ-opioid agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS binding in guinea pig hypothalamus: Effects of estrogen. Brain Res. 1998;791:341–346. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Czaja JA. Sex differences in the activational effects of gonadal hormones on food intake and body weight. Physiol. Behav. 1984;33:553–558. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czaja JA, Goy RW. Ovarian hormones and food intake in female guinea pigs and rhesus monkeys. Horm. Behav. 1975;6:329–349. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(75)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deecher DC, Alfinito PD, Leventhal L, Cosmi S, Johnston GH, Merchanthaler I, Winneker R. Alleviation of thermoregulatory dysfunction with the new serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor desvenlafaxine succinate in ovariectomized rodent models. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1376–1383. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeFazio RA, Heger S, Ojeda SR, Moenter SM. Activation of A-type gamma-aminobutyric receptors excites gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002;16:2872–2891. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deisseroth K, Mermelstein PG, Xia H, Tsien RW. Signaling from synapse to nucleus: the logic behind the mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2003;13:354–365. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dewing P, Boulware MI, Sinchak K, Christensen A, Mermelstein PG, Micevych PE. Membrane estrogen receptor-α interactions with metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a modulate female sexual receptivity in rats. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:9294–9300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0592-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dominguez R, Micevych P. Estradiol rapidly regulates membrane estrogen receptor levels in hypothalamic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:12589–12596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1038-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DonCarlos LL, Monroy E, Morrell JI. Distribution of estrogen receptor-immunoreactive cells in the forebrain of the female guinea pig. J. Comp. Neurol. 1991;305:591–612. doi: 10.1002/cne.903050406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dubal DB, Zhu H, Yu J, Rau SW, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Kindy MS, Wise PM. Estrogen receptor alpha, not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection against brain injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:1952–1957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041483198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eckersell CB, Popper P, Micevych PE. Estrogen-induced alteration of μ-opoid receptor immunoreactivity in the medial preoptic nucleas and medial amygdala. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:3967–3976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03967.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elefteriou F, Ahn JD, Takeda S, Starbuck M, Yang X, Liu X, Kondo H, Richards WG, Bannon TW, Noda M, Clement K, Valsse C, Karsenty G. Leptin regulation of bone resorption by the sympathetic nervous system and CART. Nature. 2005;434:514–520. doi: 10.1038/nature03398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elmquist JK, Bjorbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;395:535–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Endocrinologyh H, Sasaki H, Maruyama K, Takeyama K, Waga I, Shimizu T, Kato S, Kawashima H. Rapid activation of MAP Kinase by estrogen in the bone cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:99–102. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Etgen AM, Ansonoff MA, Quesada A. Mechanisms of ovarian steroid regulation of norepinephrine receptor-mediated signal transduction in the hypothalamus: Implications for female reproductive physiology. Horm. Behav. 2001;40:169–177. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S. Mutations in ligands and receptors of the leptin-melanocortin pathway that lead to obesity. Nature Clin. Pract. Endocrin. Metab. 2008;4:569–577. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Filardo EJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transactivation by estrogen via the G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: a novel signaling pathway with potential significance for breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;80:231–238. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton ARJ. Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;14:1649–1660. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.10.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Frackelton AR, Jr., Bland KI. Estrogen action via the G protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: Stimulation of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP-Mediated attenuation of the epidermal growth factor receptor-to-MAPK signaling axis. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002;16:70–84. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Filardo EJ, Thomas P. GPR30: a seven-transmembrane-spanning estrogen receptor that triggers EGF release. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;16:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flügge G, Oertel WH, Wuttke W. Evidence for estrogen-receptive GABAergic neurons in the preoptic/anterior hypothalamic area of the rat brain. Neuroendocrinol. 1986;43:1–5. doi: 10.1159/000124500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Foy MR, Xu J, Xie X, Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Berger TW. 17β-estradiol enhances NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs and long-term potentiation. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;81:925–929. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Freedman RR. Hot flashes: behavorial treatments, mechanisms, and relation to sleep. Am. J. Med. 2005;118:1245–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freedman RR, Blacker CM. Estrogen raises the sweating threshold in postmenopausal women with hot flashes. Fertil. Steril. 2002;77:487–490. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Freedman RR, Norton D, Woodward S, Cornelissen G. Core body temperature and circadian rhythm of hot flashes in meopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995;80:2354–2358. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.8.7629229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Funakoshi T, Yanai A, Shinoda K, Kawano MM, Mizukami Y. G protein-coupled receptor 30 is an estrogen receptor in the plasma membrane. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;346:904–910. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Furchgott RF. Pharmacological characterization of receptors: Its relation to radioligand-binding studies. Federation Proc. 1978;37:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gainetdinov RR, Premont RT, Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;27:107–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gearing M, Terasawa E. Luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) neuroterminals mapped using the push-pull perfusion method inb the rhesus monkey. Brain Res. Bull. 1988;21:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(88)90126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Geary N, Asarian L, Korach KS, Pfaff DW, Ogawa S. Deficits in E2-dependent control of feeding, weight gain, and cholecystokinin satiation in ER-alpha null mice. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4751–4757. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gottsch ML, Navarro VM, Zhao Z, Glidewell-Kenney C, Weiss J, Jameson JL, Clifton DK, Levine JE, Steiner RA. Regulation of Kiss1 and dynorphin gene expression in the murine brain by classical and nonclassical estrogen receptor pathways. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:9390–9395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0763-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gréco B, Allegretto EA, Telel MJ, Blaustein JD. Coexpression of ER and progestin receptor proteins in the female rat forebrain: effects of estradiol treatment. Endocrinology. 2001;142:5172–5181. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Griffin JD, Saper CB, Boulant JA. Synaptic and morphological characteristics of temperature-sensitive and -insensitive rat hypothalamic neurones. J. Physiol. 2001;537.2:521–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gruber CJ, Gruber DM, Gruber IM, Wieser F, Huber JC. Anatomy of the estrogen response element. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;15:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gu G, Rojo AA, Zee MC, Yu J, Simerly RB. Hormonal regulation of CREB phosphorylation in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3035–3044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-03035.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gu Q, Korach KS, Moss RL. Rapid action of 17beta-estradiol on kainate-induced currents in hippocampal neurons lacking intracellular estrogen receptors. Endocrinology. 1999;140:660–666. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gu Q, Moss RL. Novel mechanism for non-genomic action of 17beta-oestradiol on kainate-induced currents in isolated rat CA1 hippocampal neurones. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1998;506:745–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.745bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gu Q, Moss RL. 17beta-estradiol potentiates kainate-induced currents via activation of the cAMP cascade. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3620–3629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03620.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gundlah C, Kohama SG, Mirkes SJ, Garyfallou VT, Urbanski HF, Bethea CL. Distribution of estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) mRNA in hypothalamus, midbrain and temporal lobe of spayed macaque: continued expression with hormone replacement. Mol. Brain Res. 2000;76:191–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gundlah C, Lu NZ, Mirkes SJ, Bethea CL. Estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) mRNA and protein in serotonin neurons of macaques. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;91:14–22. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Håkansson ML, Brown H, Ghilardi N, Skoda RC, Meister B. Leptin receptor immunoreactivity in chemically defined target neurons of the hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:559–572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00559.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hammes SR, Levin ER. Extra-nuclear steroid receptors: nature and actions. Endocr. Rev. 2007;28:726–741. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Han S-K, Gottsch ML, Lee KJ, Popa SM, Smith JT, Jakawich SK, Clifton DK, Steiner RA, Herbison AE. Activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by kisspeptin as a neurocrine switch for the onset of puberty. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:11349–11356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3328-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hayward MD, Pintar JE, Low MJ. Selective reward deficit in mice lacking β-endorphin and enkephalin. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:8251–8258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08251.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Herbison AE. Somatostatin-immunoreactive neurones in the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus possess oestrogen receptors in the male and female rat. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:323–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Herbison AE. Multimodal influence of estrogen upon gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocr. Rev. 1998;19:302–330. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Herbison AE, Skynner MJ, Sim JA. Lack of detection of estrogen receptor-transcripts in mouse gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2001;142:492–493. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herbison AE, Theodosis DT. Localization of oestrogen receptors in preoptic neurons containing neurotensin but not tyrosine hydroxylase, cholecystokinin or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in the male and female rat. Neurosci. 1992;50:283–298. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90423-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hewitt SC, Deroo BJ, Hansen K, Collins J, Grissom S, Afshari C, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor-dependent genomic responses in the uterus mirror the biphasic physiological response to estrogen. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;17:2070–2083. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hill JW, Williams KW, Ye C, Luo J, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Cowley MA, Cantley LC, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK. Acute effects of leptin require PI3K signalng in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:1796–1805. doi: 10.1172/JCI32964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Horvath TL, Leranth C, Kalra SP, Naftolin F. Galanin neurons exhibit estrogen receptor immunoreactivity in the female rat mediobasal hypothalamus. Brain Res. 1995;675:321–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01374-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hrabovszky E, Kallo I, Hajszan T, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Liposits Z. Expression of estrogen receptor-beta messenger ribonucleic acid in oxytocin and vasopressin neurons of the rat supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2600–2604. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.6024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hrabovszky E, Kallo I, Steinhauser A, Merchenthaler I, Coen CW, Petersen SL, Liposits Z. Estrogen receptor-beta in oxytocin and vasopressin neurons of the rat and human hypothalamus: Immunocytochemical and in situ hybridization studies. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;473:315–333. doi: 10.1002/cne.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hrabovszky E, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Hajszan T, Carpenter CD, Liposits Z, Petersen SL. Detection of estrogen receptor-β messenger ribonucleic acid and 125I-estrogen binding sites in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons of the rat brain. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3506–3509. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.9.7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hrabovszky E, Steinhauser A, Barabas K, Shughrue PJ, Petersen SL, Merchenthaler I, Liposits Z. Estrogen receptor-beta immunoreactivity in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons of the rat brain. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3261–3264. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hu L, Wada K, Mores N, Krsmanovic LZ, Catt KJ. Essential role of G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium channels in gonadotropin-induced regulation of GnRH neuronal firing and pulsatile neurosecretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:25231–25240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang GZ, Woolley CS. Estradiol acutely suppresses inhibition in the hippocampus through a sex-specific Endocrinologycannabinoid and mGluR-dependent mechanism. Neuron. 2012;74:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Isgor C, Cecchi M, Kabbaj M, Akil H, Watson SJ. Estrogen receptor beta in the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus regulates the neuroEndocrinologycrine response to stress and is regulated by corticosterone. Neurosci. 2003;121:837–845. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jackson GL, Kuehl D. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) regulation of GnRH secretion in sheep. Reproduction. 2002;59:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jacobson D, Pribnow D, Herson PS, Maylie J, Adelman JP. Determinants contributing to estrogen-regulated expression of SK3. Biochem. Biophys. Res Commun. 2003;303:660–668. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jones MEE, Thorburn AW, Britt KL, Hewitt KN, Wreford NG, Proietto J, Oz OK, Leury BJ, Robertson KM, Yao SG, Simpson ER. Aromatase-deficient (ArKO) mice have a phenotype of increased adiposity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:12735–12740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kallo I, Butler JA, Barkovics-Kallo M, Goubillon ML, Coen CW. Oestrogen receptor beta-immunoreactivity in gonadotropin releasing hormone-expressing neurones: regulation by oestrogen. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:741–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kelly MJ, Moss RL, Dudley CA. Differential sensitivity of preoptic-septal neurons to microelectrophoresed estrogen during the estrous cycle. Brain Res. 1976;114:152–157. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)91017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kelly MJ, Moss RL, Dudley CA. The effects of ovarectomy on preoptic-septic area neurons to microelectrophoresed estrogen. Neuroendocrinol. 1978;25:204–211. doi: 10.1159/000122742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kelly MJ, Moss RL, Dudley CA. The stereospecific changes in the unit activity of preoptic-septal neurons to microelectrophoresed estrogen. In: Ryall RW, Kelly JS, editors. Iontophoresis and Transmitter Mechanisms in the Mammalian Central Nervous System. New York: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press; 1978. pp. 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kelly MJ, Moss RL, Dudley CA. The effects of microelecrophoretically applied estrogen, cortisol, and acetylcholine on medial preoptic-septal unit activity throughout the estrous cycle of the female rat. Exp. Brain Res. 1977;30:53–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00237858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kelly MJ, Moss RL, Dudley CA, Fawcett CP. The specificity of the response of preoptic-septal area neurons to estrogen: 17α-estradiol versus 17β-estradiol and the response of extrahypothalamic neurons. Exp. Brain Res. 1977;30:43–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00237857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK. Electrophysiological analysis of neuroEndocrinologycrine neuronal activity in hypothalamic slices. In: Levine JE, editor. Methods in Neurosciences: Pulsatility in Neuroendocrine Systems. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc.; 1994. pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK. Rapid membrane effects of estrogen in the central nervous system. In: Pfaff DW, editor. Hormones, Brain and Behavior. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 361–380. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK, Eskay RL. Identification of estrogen-responsive LHRH neurons in the guinea pig hypothalamus. Brain Res. Bull. 1984;12:399–407. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kenealy BP, Keen KL, Rønnekleiv OK, Terasawa E. STX, a novel nonsteroidal estrogenic compound, induces rapid action in primate GnRH neuronal calcium dynamics and peptide release. Endocrinology. 2011;152:182–191. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kesner JS, Wilson RC, Kaufman J-M, Hotchkiss J, Chen Y, Yamamoto H, Pardo RR, Knobil E. Unexpected responses of the hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone "pulse generator" to physiological estradiol inputs in the absence of the ovary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:8745–8749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kininis M, Chen BS, Diehl AG, Issacs GD, Zhang T, Siepel AC, Clark AG, Kraus WL. Genomic analyses of transcription factor binding, histone acetylation, and gene expression reveal mechanistically distinct classes of estrogen-regulated promoters. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:5090–5104. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00083-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Komm BS, Kharode YP, Bodine PVN, Harris HA, Miller CP, Lyttle CR. Bazedoxifene Acetate: a selective estrogen receptor modulator with improved selectivity. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3999–4008. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kow LM, Pfaff DW. The membrane actions of estrogens can potentiate their lordosis behavior-facilitating genomic actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12354–12357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404889101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kroll H, Bolsover S, Hsu J, Kim S-H, Bouloux P-M. Kisspeptin-evoked calcium signals in isolated primary rat gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurones. Neuroendocrinol. 2011;93:114–120. doi: 10.1159/000321678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kruijver FP, Balesar R, Espila AM, Unmehopa UA, Swaab DF. Estrogen-receptor-beta distribution in the human hypothalamus: similarities and differences with ER alpha distribution. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;466:251–277. doi: 10.1002/cne.10899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kruijver FP, Balesar R, Espila AM, Unmehopa UA, Swaab DF. Estrogen receptor-alpha distribution in the human hypothalamus in relation to sex and endocrine status. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002;454:115–139. doi: 10.1002/cne.10416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kuo J, Hariri OR, Bondar G, Ogi J, Micevych P. Membrane estrogen receptor-α interacts with metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1a to mobilize intracellular calcium in hypothalamic astrocytes. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1369–1376. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Laflamme N, Nappi RE, Drolet G, Labrie C, Rivest S. Expression and neuropeptidergic characterization of estrogen receptors (ER and ER) throughout the rat brain: Anatomical evidence of distinct roles of each subtype. J. Neurobiol. 1998;36:357–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980905)36:3<357::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lagrange AH, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Estradiol-17β and μ-opioid peptides rapidly hyperpolarize GnRH neurons: A cellular mechanism of negative feedback? Endocrinology. 1995;136:2341–2344. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7720682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lagrange AH, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Modulation of G protein-coupled receptors by an estrogen receptor that activates protein kinase A. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;51:605–612. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Leal S, Andrade JP, Paula-Barbosa MM, Madeira MD. Arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus: Effects of age and sex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;401:65–88. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19981109)401:1<65::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]