Abstract

Individual variation in serotonergic function is associated with reactivity, risk for affective disorders, as well as an altered response to disease. Our study used a nonhuman primate model to further investigate whether a functional polymorphism in the promoter region for the serotonin transporter gene helps to explain differences in proinflammatory responses. Homology between the human and rhesus monkey polymorphisms provided the opportunity to determine how this genetic variation influences the relationship between a psychosocial stressor and immune responsiveness. Leukocyte numbers in blood and interleukin-6 responses are sensitive to stressful challenges and are indicative of immune status. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and cellular interleukin-6 responses to in vitro lipopolysaccharide stimulation were assessed in 27 juvenile male rhesus monkeys while housed in stable social groups (NLL=16, NS=11) and also in 18 animals after relocation to novel housing (NLL=13, NS=5). Short allele monkeys had significantly higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios than homozygous Long allele carriers at baseline (t(25)=2.18, p=0.02), indicative of an aroused state even in the absence of disturbance. In addition, following the housing manipulation, interleukin-6 responses were more inhibited in short allele carriers (F(1,16)=8.59, p=0.01). The findings confirm that the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphism is a distinctive marker of reactivity and inflammatory bias, perhaps in a more consistent manner in monkeys than found in many human studies.

Keywords: 5-HTTLPR, Serotonin, Stress, Lipopolysaccharide, Inflammation, Interleukin-6, Allele Polymorphism, Monkey, Macaca mulatta

Introduction

Advances in genetic techniques allow researchers to identify specific genes and polymorphic variants affecting behavioral and physiological propensities associated with environmental sensitivity, which confers resilience and vulnerability. In particular, serotonergic activity and serotonin transporter (5-HTT) efficiency have been linked with reactions to social stressors, the likelihood of affective illness (Hariri & Holmes, 2006; Meyer et al., 2004; Virkkunen et al., 1995), as well as immune functioning (Khan & Ghia, 2010; Meredith et al., 2005; Mössner et al., 2009; Mössner & Lesch, 1998; Paiardini et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2007). 5-HTT transcription is modulated by length polymorphism in the promoter region of the SLC4A6 gene (Heils, et al., 1996). In vitro studies have shown that carriers of the shorter variant of 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) have reduced gene expression (Heils et al., 1996; Lesch et al., 1998; Praschak-Rieder et al., 2007) and slower 5-HT reuptake (Balija et al., 1; Greenberg et al., 1999; Singh et al., 2011; Yogesh et al., 2011). Short (S) allele carriers also have increased amygdala activity (Hariri, et al., 2002; Kalin et al., 2008; Canli & Lesch, 2007), larger cortisol responses (Baldwin & Taylor, 2010; Gotlib, et al., 2008; Mueller et al., 2011), elevated norepinephrine (Otte et al, 2007), and differential drug responses (Rausch et al., 2005). Similarly, the S allele has been linked to trait anxiety (Lesch et al., 1996), susceptibility to depression (Caspi et al., 2003), and aggressiveness (Kinnally et al., 2010). However, a number of studies in humans have also failed to replicate these findings (Sen et al., 2004). As a consequence, some have suggested more recently that this polymorphism should be characterized instead as an indicator of behavioral plasticity (Belsky et al., 2009: Chiao et al., 2010; Homberg & Lesch, 2011; Kuepper et al., 2012).

Rhesus macaques have analogous variation of the 5-HTTLPR (Lesch et al., 1997). The S allele, both in homozygous and heterozygous animals, has been associated with differences in 5-HTT functioning (Bennett et al., 2002), as well as behavioral and hormonal reactivity (Champoux et al., 2002; Kalin et al., 2008). These propensities are most evident in monkeys raised by humans in a nursery setting without normal maternal stimulation and care (Bennett et al., 2002; Suomi, 2006; Bennett & Pierre, 2010). Thus, one goal was to investigate the strength of the association between the genotype and reactivity in normal mother-reared monkeys, evaluated both in an undisturbed setting and under moderate challenge induced by relocation. Prior primate studies have demonstrated the potency of relocation to a novel cage or social group as a probe of emotional reactivity (Capitanio & Lerche, 1998; Sloan et al., 2007; Willette et al., 2007).

Individuals also vary markedly in their proinflammatory physiology, especially following stressful challenges (Bartolomucci, et al., 2005; Capitanio et al., 1998; Sgoifo et al., 2005). Our research took advantage of this strong relationship between neurobehavioral reactivity and inflammatory physiology (Avitsur et al., 2006; Capitanio, 2010; Coe & Lubach, 2005). For example, it has been known for decades that alterations in cell numbers and trafficking in the blood stream can be employed as a sensitive index of arousal and stress both in humans and animals (Cannon, 1929; Coe, 1993; Selye, 1936). Psychological stressors increase the number and proportion of neutrophils in circulation at the same time that lymphocytes are redistributed out of the blood stream (Capitanio et al., 2011, Cole, 2008; Cole et al., 2009, Costanzo et al., 2011, Dhabhar et al., 1996). In addition, cellular responses to in vitro lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation were used to further characterize the monkeys’ immune phenotype. Hormonal and autonomic responses to stress have been shown to differentially inhibit Interleukin-6 (IL-6) release and signaling (Ahmed & Ivashkiv, 2000; Borovikova et al., 2000; Elenkov & Webster, 2006; O’Connor et al., 2000) The a priori prediction was that the S allele would confer a heightened stress responsiveness, evident in both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios and cellular responses.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Twenty-seven juvenile male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), mean age 1.9 years (SD=0.5], were assessed in this research. Only male subjects were used in order to exclude the contribution of sex differences in behavior, physiology, and social ranking. All were mother-reared, and similarly housed in stable social groups of 5–6 peers in standard pen cages (0.9 × 1.8 × 1.8 m) at the Harlow Primate Laboratory. Environmental conditions were standardized: room temperature was maintained at 21 °C and light/dark cycles were 14:10 with lights on at 0600. Animals were fed commercial chow (PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO) daily at 0700, supplemented with fresh fruit several times a week, and water was available ad libitum. In addition to social housing, all animals received extensive environmental enrichment, including the provision of plastic toys, foraging devices, puzzles, and music.

Experimental design

All 27 monkeys were initially evaluated under undisturbed baseline conditions in stable peer social groups and then a subset of 18 were examined again after a period of moderate disturbance. The social stress condition involved re-housing each monkey with a single unfamiliar partner in a smaller novel cage (0.9 × 1.8 × 0.9 m) for 1–3 weeks. Unfamiliar partners were of similar age and size, but mixed genders. Initially, a wire mesh panel separated the pair to ensure their compatibility and safety, and then it was removed, permitting the pair to interact. All procedures and housing arrangements were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Specimen collection and assays

Blood samples were collected at two time points: at baseline and approximately 3 weeks after re-housing. Specimens were always collected in the morning between 0830–1000. Blood (3–5.0 mL) was rapidly collected from non-anesthetized awake subjects by femoral venipuncture into EDTA-treated vacutainers. To minimize the inadvertent influence of acute handling and/or a delay in collection, specimens were obtained from a maximum of 3 subjects on a given sampling day. The blood was used to determine a Complete Blood Count (by General Medical Laboratories, Madison, WI) and to set up whole blood cultures, which were stimulated with LPS (E. coli derived). Blood was diluted 1:1 in culture medium (RPMI 1640; 1 mM sodium pyruvate; 1 nM non-essential amino acids; 25 μg/mL gentamicin; 1 U/mL penicillin G sodium; 1μg/mL streptomycin sulfate; 2.5 ng/mL amphotericin B; 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol; 2 mM L-glutamine; 0.075% NaHCO3). The blood was incubated in duplicate in 12-well plates, total volume of 500 μL per well, with or without 10 ng/mL LPS, for 24 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Supernatants were then collected and frozen at −60 °C until thawed for cytokine assays. Supernatant IL-6 concentrations were quantified with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits using antibody targeted at human IL-6 (ELISA; RnD Quantakine, Minneapolis, MN), but known to cross-react with the IL-6 protein of macaques.

Rh5-HTTLPR genotyping

On a different occasion, blood (3–5 mL) was obtained from each monkey to determine its 5HTTLPR genotype. DNA was isolated from fresh leukocyte preparations using a Puregene DNA Purification System (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Only DNA isolates with an A260/A280 absorbance ratio of at least 1.5 were used for the amplification. PCR amplification was undertaken using the Roche GC-Rich kit (Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s directions. PCR amplifications were carried out using the primer set 5HTTLPR-F (5′- CGT TGC CGC TCT GAA TGC CAG C -3′) and 5HTTLPR-R (5′- GGT GCC ACC TAG ACG CCA GGG C -3′) in a volume of 20 μL containing 200 μM each of dATP, dTTP, dCTP, dGTP, 0.375 μM forward and reverse primers, 50 ng DNA, 1 M Roche GC-Rich resolution solution, 1 U enzyme, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 1x enzyme buffer in a Perkin Elmer 9700 thermocycler (Boston, MA). PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C × 3 min initial denaturation, followed by 32 cycles of 95 °C × 60 s, 67 °C × 30 s, 72 °C × 60 s, followed by a final extension step of 7 min at 72 °C. PCR products were analyzed using electrophoresis on a 6% TBE, 6% urea, denaturing gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The gels were visualized on a FMBIO II (Hitachi, Tokyo) using FMBIO II ReadImage 1.1 program. (Bennett et al., 2002). Genotyping revealed 16 LL and 11 LS/SS carriers. The baseline and challenge conditions comprised 16 LL and 11 S and 13 LL and 5 S subjects, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios and cytokine levels were natural log-transformed to achieve normal distributions. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio data were analyzed with paired-sample t tests to verify the effects of relocation, and with independent-sample t tests for the effect of genotype during each housing condition. This use of t tests allowed us to assess all subjects available, including the 9 not available for a second sample in the re-housing condition. However, we did apply mixed model ANOVAs to the IL-6 data from the 18 monkeys with 2 samples. The influence of relocation and genotype were also considered separately because IL-6 levels were affected by leukocyte numbers in circulation; thus, IL-6 data were divided by the number of mononuclear cells (MNC) and reanalyzed. Based on finding an inhibitory effect of relocation on cytokine responses, the moderating influence of genotype was further tested by one-tailed, paired-sample t tests.

Results

Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratios

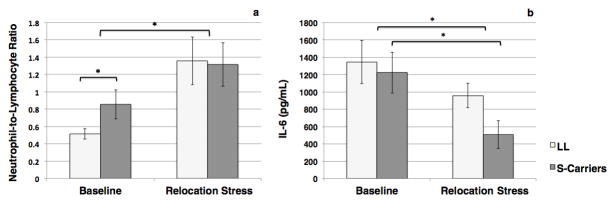

In keeping with predictions, there was an overall effect of relocation stress on the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in the blood (t(17)=minus;3.80, p=0.001) (Fig. 1a). The rehousing resulted in a marked cellular demargination, causing a sustained increase in the number and percentage of neutrophils in circulation, and an egress of lymphocytes from blood to tissue (Table 1). This redistribution of the two cell types was complementary and thus the Total WBC number was not affected. Carriers of the S allele had a higher Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio in the baseline condition (t(25)=2.18, p=0.02), a difference that became non-significant following rehousing (t(16)=−0.09, p=0.85).

Figure 1. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratios and Interleukin-6 Responses.

Mean values (+/− SE) values displayed for LL and S-carrier monkeys at Baseline (NLL=16, NS=11) and after Relocation Stress (NLL=13, NS=5). Relocation markedly affected the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and IL-6 levels in the LPS stimulated whole blood cultures. S-carriers had significantly higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios in the undisturbed condition and underwent greater stress-induced inhibition of IL-6 responses.

Table 1.

Mean (SE) results from the Complete Blood Counts for the L homozygous and S carrier monkeys during the baseline condition (N=27) and after the relocation challenge (N=18).

| Cells | Mean (SE) | Significance (p-value) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After Relocation | Relocation Stress | LL v. S carrier | ||||

| LL | S carrier | LL | S carrier | Baseline | After Relocation | ||

| Total White Blood Cells per mL | 9.8 (0.5) | 9.5 (0.6) | 9.0 (0.5) | 9.7 (0.5) | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 31.0 (2.3) | 41.5 (3.8) | 48.9 (4.4) | 53.0 (7.1) | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.63 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 63.9 (2.0) | 55.3 (3.6) | 46.0 (4.3) | 45.6 (6.9) | 0.003 | 0.04 | 0.96 |

Interleukin-6

Following relocation there was a significant decrease in the cellular IL-6 response to LPS stimulation (F(1, 16)=14.29, p=0.002) (Fig. 1b), as well as a stress-by-genotype interaction (F(1,16)=4.37, p=0.05). The relocation challenge markedly inhibited IL-6 responses in S-carriers (t(4)=3.00, p=0.02), but had a more marginal effect on LL carriers (t(12)=−1.70, p=0.06). Because IL-6 release in vitro can be affected by MNC numbers in whole blood cultures, and both genotype and housing condition affected cell numbers, the IL-6 values were also examined after correcting for MNC number. After adjusting the IL-6 values, the effect of the rehousing manipulation retained statistical significance, but with decreased effect size (F(1, 16)=8.59, p=0.01), suggesting that the stress-induced shift in cell number had only partially accounted for the decrease in IL-6. Genotype continued to have a modulatory effect on the stress-induced inhibition after the cell count corrections (F(1,16)=5.52, p=0.03). After this adjustment for MNC, the inhibitory effect of stress remained evident in S-carriers (t(4)=2.52, p=0.03), while attenuating the effect on LL carriers (t(12)=0.61, p=0.28), highlighting the interactive effect of genotype and reactivity to challenge.

Discussion

Our assessment of young rhesus monkeys has confirmed that the arousal associated with rehousing has sustained effects on their immune responses, a finding that replicates and extends the reports of many other immune alterations associated with social stress in nonhuman primates (Coe, 1993; Coe & Laudenslager, 2007). In keeping with previous papers indicating that S-carriers are more likely to exhibit an anxious temperament (Champoux et al., 2002; Hariri et al., 2006), we hypothesized these monkeys would have a higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio than their LL counterparts while in undisturbed housing conditions. We also predicted that S-carriers would undergo greater inhibition of cellular IL-6 responses to LPS stimulation after rehousing to a new cage and the arousal associated with forming a new social relationship with an unfamiliar monkey.

The presence of more neutrophils in circulation has long been associated with the aroused state, reflecting the detachment from vascular walls and translocation from tissue (Cole et al., 2009; Coe, 2003; Dhabhar, et al., 1996). While this cellular demargination can also be a marker of bacterial infection, the latter is typically manifested by a large increase in total leukocyte count (Busch, et al., 1998; Carl, 2006). Apart from the effects on cell numbers, the release of glucocorticoids in response to acute stressors has also been associated with an inhibition of IL-6 responses to endotoxins (Ahmed & Ivashkiv, 2000; Akira & Kishimoto, 1992; Tobler et al., 1992; Waage et al., 1990; Zitnik et al., 1994). This inhibition of cellular reactions is distinct from the in vivo increase in IL-6 secretion from many nonlymphoid tissues, which has described as the proinflammatory bias seen after sustained psychological stress and sometimes in glucocorticoid resistance states, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2003; Lutgendorf et al., 1999; Maes et al., 1998; Miller et al., 2002).

In our study, the cellular shift reflected the relative proportion of neutrophils-to-lymphocytes, without a change in the overall white blood cell number, which is more indicative of an aroused state. Monkeys from both genotypes showed the upward shift in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios after relocation, but the S-carriers had already exhibited higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios than LL monkeys in the undisturbed condition. Because of the similar response to rehousing, the influence of genotype was no longer statistically significant. Similarly, the relocation induced a marked inhibition of the IL-6 response to LPS in vitro. But the decrease was only partially due to the number of cells in the culture. After adjusting the IL-6 values by MNC counts, the main effect of rehousing retained its significance. The IL-6 value adjusted by cell number enabled us to detect the influence of genotype, with the extent of IL-6 inhibition being greater in the S carriers. Our findings reinforce the view that social and environmental context, especially with respect to arousing aspects of challenge and adversity, are important to consider when profiling the immune status of the individual (Avitsur et al., 2006; Capitanio et al., 2008). Rehousing these monkeys with unfamiliar mates induced sustained changes cell numbers in circulation and how the cells responded to stimulation with bacterial proteins. Cell differentials were employed as some of the earliest indicators of the stressed state, used by Walter Cannon (1929) and later by Hans Selye in his classic research describing the “General Adaptation Syndrome” (1932). It is important to consider that cell trafficking is a critical component of the host’s adaptive reaction to infections, another type of threat and challenge to the body, when neutrophils are mobilized into circulation and lymphocytes egress to lymph nodes and spleen (Engler et al., 2004). While the shift in cell populations observed following rehousing wasn’t of the same magnitude as seen during infection, the location of cells would influence the competence of the response to infectious pathogens and ability to survey for non-self antigens (Tseng et al., 2005). Accordingly, studies in humans have associated high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios with poorer control of influenza virus infections as well as higher all-cause mortality rates (Dahbhar et al., 1996; Leng et al., 2005; Poludasu et al., 2009; Smith & Wang, 2012; Zahorec, 2001). In rodent models, detailed analyses have demonstrated how the stress of rehousing or the introduction of a social intruder affects the MNC and macrophage populations in the spleen, impacting the response to pathogen exposure (Kinsey et al., 2008). Many of these cellular changes are induced by neuroendocrine activation, especially the potent immunomodulatory actions of cortisol (Engler et al., 2005). But the secretory release of cytokines, such as IL-6 and other chemokines, also provide soluble signals for cell migration and proliferation (Gordon et al., 1992; Hurst et al., 2001). Moreover, the release of serotonin by activated platelets in aroused individuals is also known to influence cell trafficking by affecting vascular permeability (Hutchison et al., 1959; Lekakis et al., 2010, Mercado & Kilic, 2010). Although we did not measure serotonin levels in this study, previous studies in monkeys have demonstrated that serotonergic functioning in S carriers differs from LL monkeys, and thus may affect the immune processes we assessed in this research. Many components of the serotonergic system, including the serotonin transporter, are expressed and functionally active in immune cells (Mössner & Lesch, 1998). Lymphocytes, in particular, express the transporter and have been shown to vary in 5-HT uptake rates by 5-HTTLPR genotype (Singh, 2011).

Numerous papers on humans and monkeys have reported that carriers of the S allele are more reactive, emotionally and physiologically (Gotlib et al., 2008; Muller et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2009; Way & Taylor, 2010). Our study took advantage of the known arousal associated with relocation to a novel setting and the formation of new social relationship in order to assess the differential reactions of the L and S carrier. Conclusions about the impact of this genotype in humans have been modified by several inconsistent findings, and the polymorphism now tends to be viewed as a marker of environmental sensitivity, rather than as a simple indicator of vulnerability to pathology, deviant behavior or mental illness (Beevers et al., 2011; Kuepper et al., 2012; Mileva-Seitz et al., 2011; Way & Lieberman, 2010). The latter interpretation would concur with the research in monkeys demonstrating that the influence of the S allele becomes more pronounced following adverse rearing conditions, such as an early separation from the mother and nursery rearing (Bennett et al., 2002; Suomi, 2006). But our study indicates that some physiological effects can also be found even in mother-reared monkeys when they are housed in undisturbed conditions.

Notwithstanding these straightforward findings in primates, several limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. Although it was possible to detect the influence of genotype, the number of S carriers was small for a thorough investigation of gene-by-behavior interactions. The prevalence of the S allele among the monkeys in this experiment was in keeping with its typical distribution in most rhesus monkey colonies, approximately 1:4, and the homozygous SS animal is more rare. Like other laboratory studies with relatively small number of animals however, the chance of delineating significant genotype associations can be enhanced by the level of experimental control that lessens extraneous variation between subjects. For example, all animals in this study lived in standardized conditions, were raised in the same manner from birth and had the same diet, housing, light schedules, and ambient environmental conditions. It should also be emphasized that the assessment of IL-6 responses was performed under controlled conditions in vitro, using an assay that evaluates the cellular capacity to respond to a bacterial stimulant. Other studies have evaluated levels of IL-6 in circulation (Fredericks et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2009; Paiardini et al., 2009), where it provides a more general measure of synthesis and release by many different cells, including non-lymphoid tissues, such as adipocytes (Bastard et al., 1999; Kishimoto, 1989). Then, it is interpreted as an index of the proinflammatory state of the host. Based on the current findings, it would be important to conduct an in vivo assessment of monkeys that differ in their rh5-HTTLPR genotype. In the light of recent research, we would predict that S carriers might present a more inflammatory phenotype. The differences in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios and IL-6 responses to LPS between the LL and S carriers also speak to the need for a more detailed analysis of cellular receptors for signaling proteins, such as the serotonin receptors and transporters on blood cells. These have been well characterized in both humans and murine models, but less is known about these serotonergic features on different cell populations in monkeys, especially among ones differing in this allele polymorphism (Abdough et al., 2004; Connell et al., 2006; Kubera et al., 2005; Maes et al., 2005; Müller et al., 2009).

Although further research is needed, the rh5-HTTLPR polymorphism appears to be a sensitive marker of physiological arousal and immune reactivity in the rhesus monkey. Our data suggest that the immune measures observed reflect genotype-related differences in temperament, which are downstream effects of limbic activation and neuroendocrine processes (Avitsur et al., 2006; Capitanio, 2010), and the direct effect of genotype on immune cells via differences in serotonin transporter function (Singh et al., 2011). Larger surveys of monkeys from this colony have shown that temperament and reactivity to threat are associated not only with the rh5-HTTLPR polymorphism, but also with other genetic variation, including with genes linked to corticotropin releasing hormone and amygdala activity (Bakshi & Kalin, 2000; Rogers et al., 2008), which may affect immune functioning both directly and indirectly. Collectively, this research demonstrates the value of primate models for investigating genotypic influences, enabling us to explain how neurobehavioral and immune processes are regulated and modulated by individual genes in concert with other allele polymorphisms and myriad influences of the environment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a supplement issued under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to a NIH grant (AI067518-05S1, PI: Coe) and by the NIMH grant (5T32MH018931) for the Training Program in Emotion Research. Some staff support was enabled by a Grand Challenges Explorations award from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (PI: Coe). The invaluable assistance of D. Brar and A. Slukvina should also be acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdouh M. 5-HT1A-mediated promotion of mitogen-activated T and B cell survival and proliferation is associated with increased translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:24–34. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(03)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed ST, Ivashkiv LB. Inhibition of IL-6 and IL-10 signaling and Stat activation by inflammatory and stress pathways. J Immunol. 2000;165:5227–5237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S. IL-6-regulated transcription factors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:1401–1418. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Kishimoto T. IL-6 and NF-IL6 in acute-phase response and viral infection. Immunol Rev. 1992;127:25–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avitsur R, Padgett DA, Sheridan JF. Social interactions, stress, and immunity. Neurol Clin. 2006;24:483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi VP, Kalin NH. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and animal models of anxiety: gene-environment interactions. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:1175–1198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balija M, Bordukalo-Niksic T, Mokrovic G, Banovic M, Cicin-Sain L, Jernej B. Serotonin level and serotonin uptake in human platelets: a variable interrelation under marked physiological influences. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomucci A, Palanza P, Sacerdote P, Panerai AE, Sgoifo A, Dantzer R, Parmigiani S. Social factors and individual vulnerability to chronic stress exposure. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastard JP, Jardel C, Delattre J, Hainque B, Bruckert E, Oberlin F. Evidence for a link between adipose tissue interleukin-6 content and serum C-reactive protein concentrations in obese subjects. Circulation. 1999;99:2221–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Marti CN, Lee HJ, Stote DL, Ferrell RE, Hariri AR, Telch MJ. Associations between serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism and gaze bias for emotional information. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:187–197. doi: 10.1037/a0022125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jonassaint C, Pluess M, Stanton M, Brummett B, Williams R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes? Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:746–754. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AJ, Lesch KP, Heils A, Long JC, Lorenz JG, Shoaf SE, Champoux M, Suomi SJ, Linnoila MV, Higley JD. Early experience and serotonin transporter gene variation interact to influence primate CNS function. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:118–122. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR, Wang H, Abumrad N, Eaton JW, Tracey KJ. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405:458–462. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch DH, Pilip IM, Vijh S, Pamer EG. Coordinate regulation of complex T cell populations responding to bacterial infection. Immunity. 1998;8:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Lesch KP. Long story short: the serotonin transporter in emotion regulation and social cognition. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1103–1109. doi: 10.1038/nn1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon WB. Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage. 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP. Individual differences in emotionality: social temperament and health. Am J Primatol. 2011;73:507–515. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Abel K, Mendoza SP, Cole SW, Mason WA. Personality and serotonin transporter genotype interact with social context to affect immunity and viral set-point in simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2008:629. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Lerche NW. Social separation, housing relocation, and survival in simian AIDS: a retrospective analysis. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:235–244. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Cole SW. Nervous temperament in infant monkeys is associated with reduced sensitivity of leukocytes to cortisol’s influence on trafficking. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Lerche NW. Individual differences in peripheral blood immunological and hormonal measures in adult male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): evidence for temporal and situational consistency. Am J Primatol. 1998;44:29–41. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1998)44:1<29::AID-AJP3>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champoux M, Bennett A, Shannon C, Higley JD, Lesch KP, Suomi SJ. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism, differential early rearing, and behavior in rhesus monkey neonates. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:1058–1063. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Blizinsky KD. Culture-gene coevolution of individualism-collectivism and the serotonin transporter gene. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277:529–537. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe CL. Psychosocial factors and immunity in nonhuman primates: a review. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:298–308. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe CL, Laudenslager ML. Psychosocial influences on immunity, including effects on immune maturation and senescence. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:1000–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe CL, Lubach GR. Critical periods of special health relevance for psychoneuroimmunology. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. Social regulation of leukocyte homeostasis: the role of glucocorticoid sensitivity. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Mendoza SP, Capitanio JP. Social stress desensitizes lymphocytes to regulation by endogenous glucocorticoids: insights from in vivo cell trafficking dynamics in rhesus macaques. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:591–597. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181aa95a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo ES, Sood AK, Lutgendorf SK. Biobehavioral influences on cancer progression. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2011;31:109–132. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS, Miller AH, McEwen BS, Spencer RL. Stress-induced changes in blood leukocyte distribution. Role of adrenal steroid hormones. J Immunol. 1996;157:1638–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov I, Webster E. Stress, Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone, Glucocorticoids, and the Immune/Inflammatory Response: Acute and Chronic Effects. Annals of the New …. 2006;876:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler H, Bailey MT, Engler A, Sheridan JF. Effects of repeated social stress on leukocyte distribution in bone marrow, peripheral blood and spleen. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;148:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler H, Engler A, Bailey MT, Sheridan JF. Tissue-specific alterations in the glucocorticoid sensitivity of immune cells following repeated social defeat in mice. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;163:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks CA, Drabant EM, Edge MD, Tillie JM, Hallmayer J, Ramel W, Kuo JR, Mackey S, Gross JJ, Dhabhar FS. Healthy young women with serotonin transporter SS polymorphism show a pro-inflammatory bias under resting and stress conditions. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon TP, Gust DA, Wilson ME, Ahmed-Ansari A, Brodie AR, McClure HM. Social separation and reunion affects immune system in juvenile rhesus monkeys. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:467–472. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90166-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Joormann J, Minor KL, Hallmayer J. HPA axis reactivity: a mechanism underlying the associations among 5-HTTLPR, stress, and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:847–851. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg BD, Tolliver TJ, Huang SJ, Li Q, Bengel D, Murphy DL. Genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter region affects serotonin uptake in human blood platelets. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Drabant EM, Weinberger DR. Imaging genetics: perspectives from studies of genetically driven variation in serotonin function and corticolimbic affective processing. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:888–897. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Holmes A. Genetics of emotional regulation: the role of the serotonin transporter in neural function. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Kolachana B, Fera F, Goldman D, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science. 2002;297:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Stober G, Riederer P, Bengel D, Lesch KP. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. J Neurochem. 1996;66:2621–2624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg JR, Lesch KP. Looking on the bright side of serotonin transporter gene variation. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood KE, Halpern CT, Greenberg G, Lerner RM. Handbook of Developmental Science, Behavior, and Genetics. 2010. pp. 353–399. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst SM, Wilkinson TS, McLoughlin RM, Jones S, Horiuchi S, Yamamoto N, Rose-John S, Fuller GM, Topley N, Jones SA. II-6 and its soluble receptor orchestrate a temporal switch in the pattern of leukocyte recruitment seen during acute inflammation. Immunity. 2001;14:705–714. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison HE, Stark JM, Chapman JA. Platelet serotonin and normal haemostasis. J Clin Pathol. 1959;12:265–267. doi: 10.1136/jcp.12.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idova G, Davydova S, Alperina E, Cheido M, Devoino L. Serotoninergic mechanisms of immunomodulation under different psychoemotional states: I. A role of 5-HT 1A receptor subtype. Int J Neurosci. 2008;118:1594–1608. doi: 10.1080/00207450701768887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Fox AS, Rogers J, Oakes TR, Davidson RJ. The serotonin transporter genotype is associated with intermediate brain phenotypes that depend on the context of eliciting stressor. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:1021–1027. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan WI, Ghia JE. Gut hormones: emerging role in immune activation and inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161:19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnally EL, Tarara ER, Mason WA, Mendoza SP, Abel K, Lyons LA, Capitanio JP. Serotonin transporter expression is predicted by early life stress and is associated with disinhibited behavior in infant rhesus macaques. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey SG, Bailey MT, Sheridan JF, Padgett DA. The inflammatory response to social defeat is increased in older mice. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T. The biology of interleukin-6. Blood. 1989;74:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubera M, Maes M, Kenis G, Kim YK, Lason W. Effects of serotonin and serotonergic agonists and antagonists on the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6. Psychiatry Res. 2005;134:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuepper Y, Wielpuetz C, Alexander N, Mueller E, Grant P, Hennig J. 5-HTTLPR S-allele: a genetic plasticity factor regarding the effects of life events on personality? Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11:643–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekakis J, Ikonomidis I, Papoutsi Z, Moutsatsou P, Nikolaou M, Parissis J, Kremastinos DT. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors decrease the cytokine-induced endothelial adhesion molecule expression, the endothelial adhesiveness to monocytes and the circulating levels of vascular adhesion molecules. Int J Cardiol. 2010;139:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng S, Xue QL, Huang Y, Semba R, Chaves P, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried L, Walston J. Total and differential white blood cell counts and their associations with circulating interleukin-6 levels in community-dwelling older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:195–199. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng SX, Xue QL, Huang Y, Ferrucci L, Fried LP, Walston JD. Baseline total and specific differential white blood cell counts and 5-year all-cause mortality in community-dwelling older women. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:982–987. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Meyer J, Glatz K, Flugge G, Hinney A, Hebebrand J, Klauck SM, Poustka A, Poustka F, Bengel D, Mossner R, Riederer P, Heils A. The 5-HT transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) in evolutionary perspective: alternative biallelic variation in rhesus monkeys. Rapid communication. J Neural Transm. 1997;104:1259–1266. doi: 10.1007/BF01294726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Mossner R. Genetically driven variation in serotonin uptake: is there a link to affective spectrum, neurodevelopmental, and neurodegenerative disorders? Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:179–192. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf SK, Garand L, Buckwalter KC, Reimer TT, Hong SY, Lubaroff DM. Life stress, mood disturbance, and elevated interleukin-6 in healthy older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M434–439. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.9.m434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Kenis G, Kubera M, De Baets M, Steinbusch H, Bosmans E. The negative immunoregulatory effects of fluoxetine in relation to the cAMP-dependent PKA pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Song C, Lin A, De Jongh R, Van Gastel A, Kenis G, Bosmans E, De Meester I, Benoy I, Neels H, Demedts P, Janca A, Scharpe S, Smith RS. The effects of psychological stress on humans: increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and a Th1-like response in stress-induced anxiety. Cytokine. 1998;10:313–318. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado CP, Kilic F. Molecular mechanisms of SERT in platelets: regulation of plasma serotonin levels. Mol Interv. 2010;10:231–241. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.4.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith EJ, Chamba A, Holder MJ, Barnes NM, Gordon J. Close encounters of the monoamine kind: immune cells betray their nervous disposition. Immunology. 2005;115:289–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JH, Houle S, Sagrati S, Carella A, Hussey DF, Ginovart N, Goulding V, Kennedy J, Wilson AA. Brain serotonin transporter binding potential measured with carbon 11-labeled DASB positron emission tomography: effects of major depressive episodes and severity of dysfunctional attitudes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1271–1279. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileva-Seitz V, Kennedy J, Atkinson L, Steiner M, Levitan R, Matthews SG, Meaney MJ, Sokolowski MB, Fleming AS. Serotonin transporter allelic variation in mothers predicts maternal sensitivity, behavior and attitudes toward 6-month-old infants. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:325–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Cohen S, Ritchey AK. Chronic psychological stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: a glucocorticoid-resistance model. Health Psychol. 2002;21:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossner R, Lesch KP. Role of serotonin in the immune system and in neuroimmune interactions. Brain Behav Immun. 1998;12:249–271. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossner R, Stiens G, Konig IR, Schmidt D, Platzer A, Kruger U, Reich K. Analysis of a functional serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism in psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:443–447. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0909-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller A, Armbruster D, Moser DA, Canli T, Lesch KP, Brocke B, Kirschbaum C. Interaction of serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region and stressful life events predicts cortisol stress response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1332–1339. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller A, Brocke B, Fries E, Lesch KP, Kirschbaum C. The role of the serotonin transporter polymorphism for the endocrine stress response in newborns. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller T, Durk T, Blumenthal B, Grimm M, Cicko S, Panther E, Sorichter S, Herouy Y, Di Virgilio F, Ferrari D, Norgauer J, Idzko M. 5-hydroxytryptamine modulates migration, cytokine and chemokine release and T-cell priming capacity of dendritic cells in vitro and in vivo. PloS one. 2009;4:e6453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DL, Fox MA, Timpano KR, Moya PR, Ren-Patterson R, Andrews AM, Holmes A, Lesch KP, Wendland JR. How the serotonin story is being rewritten by new gene-based discoveries principally related to SLC6A4, the serotonin transporter gene, which functions to influence all cellular serotonin systems. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:932–960. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell PJ, Wang X, Leon-Ponte M, Griffiths C, Pingle SC, Ahern GP. A novel form of immune signaling revealed by transmission of the inflammatory mediator serotonin between dendritic cells and T cells. Blood. 2006;107:1010–1017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TM, O’Halloran DJ, Shanahan F. The stress response and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: from molecule to melancholia. QJM. 2000;93:323–333. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.6.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte C, McCaffery J, Ali S, Whooley MA. Association of a serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) with depression, perceived stress, and norepinephrine in patients with coronary disease: the Heart and Soul Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1379–1384. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiardini M, Hoffman J, Cervasi B, Ortiz AM, Stroud F, Silvestri G, Wilson ME. T-cell phenotypic and functional changes associated with social subordination and gene polymorphisms in the serotonin reuptake transporter in female rhesus monkeys. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poludasu S, Cavusoglu E, Khan W, Marmur JD. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of long-term mortality in African Americans undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:E6–E10. doi: 10.1002/clc.20503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praschak-Rieder N, Kennedy J, Wilson AA, Hussey D, Boovariwala A, Willeit M, Ginovart N, Tharmalingam S, Masellis M, Houle S, Meyer JH. Novel 5-HTTLPR allele associates with higher serotonin transporter binding in putamen: a [(11)C] DASB positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch JL. Initial conditions of psychotropic drug response: studies of serotonin transporter long promoter region (5-HTTLPR), serotonin transporter efficiency, cytokine and kinase gene expression relevant to depression and antidepressant outcome. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1046–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Shelton SE, Shelledy W, Garcia R, Kalin NH. Genetic influences on behavioral inhibition and anxiety in juvenile rhesus macaques. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. Nature. 1936:138. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.2.230a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S, Burmeister M, Ghosh D. Meta-analysis of the association between a serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and anxiety-related personality traits. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;127B:85–89. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgoifo A, Coe C, Parmigiani S, Koolhaas J. Individual differences in behavior and physiology: causes and consequences. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh YS, Sawarynski LE, Michael HM, Ferrell RE, Swain GM, Patel BA, Andrews AM. Boron-Doped Diamond Microelectrodes Reveal Reduced Serotonin Uptake Rates in Lymphocytes from Adult Rhesus Monkeys Carrying the Short Allele of the 5-HTTLPR. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2011;1:49–64. doi: 10.1021/cn900012y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Capitanio JP, Tarara RP, Mendoza SP, Mason WA, Cole SW. Social stress enhances sympathetic innervation of primate lymph nodes: mechanisms and implications for viral pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8857–8865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1247-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AS, Wang Z. Salubrious effects of oxytocin on social stress-induced deficits. Horm Behav. 2012;61:320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomi SJ. Risk, resilience, and gene x environment interactions in rhesus monkeys. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:52–62. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler A, Meier R, Seitz M, Dewald B, Baggiolini M, Fey MF. Glucocorticoids downregulate gene expression of GM-CSF, NAP-1/IL-8, and IL-6, but not of M-CSF in human fibroblasts. Blood. 1992;79:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng RJ, Padgett DA, Dhabhar FS, Engler H, Sheridan JF. Stress-induced modulation of NK activity during influenza viral infection: role of glucocorticoids and opioids. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virkkunen M, Goldman D, Nielsen DA, Linnoila M. Low brain serotonin turnover rate (low CSF 5-HIAA) and impulsive violence. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1995;20:271–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waage A, Slupphaug G, Shalaby R. Glucocorticoids inhibit the production of IL6 from monocytes, endothelial cells and fibroblasts. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2439–2443. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way BM, Lieberman MD. Is there a genetic contribution to cultural differences? Collectivism, individualism and genetic markers of social sensitivity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010;5:203–211. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way BM, Taylor SE. The serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism is associated with cortisol response to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way BM, Taylor SE. Social influences on health: is serotonin a critical mediator? Psychosom Med. 2010;72:107–112. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ce6a7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang GB, Qiu CL, Aye P, Shao Y, Lackner AA. Expression of serotonin transporters by peripheral blood mononuclear cells of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Cell Immunol. 2007;248:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitnik RJ, Whiting NL, Elias JA. Glucocorticoid inhibition of interleukin-1-induced interleukin-6 production by human lung fibroblasts: evidence for transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:643–650. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.6.7516173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]