Abstract

Context

Both bullies and victims of bullying are at risk for psychiatric problems in childhood, but it is unclear if this elevated risk extends into early adulthood.

Objective

To test whether bullying and being bullied in childhood predicts psychiatric and suicidality in young adulthood after accounting for childhood psychiatric problems and family hardships.

Design

Prospective, population-based study of 1420 subjects with being bullied and bullying assessed four to six times between ages 9 and 16. Subjects were categorized as bullies only, victims only, bullies and victims (bully-victims), or neither.

Setting and population

Community sample

Main Outcome Measure

Psychiatric outcomes included depression, anxiety, antisocial personality disorder, substance disorders, and suicidality (including recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or a suicide attempt) were assessed in young adulthood (ages 19, 21, and 24/25/26) by structured diagnostic interviews.

Results

Victims and bully-victims had elevated rates of young adult psychiatric disorder, but also elevated rates of childhood psychiatric disorders and family hardships. After controlling for childhood psychiatric problems or family hardship, victims continued to have higher prevalence of agoraphobia (odds ratio (OR), 4.6; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.7–12.5, p <0.01), generalized anxiety (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.1–6.3, p <0.001), and panic disorder (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.5–6.5, p <0.01), and bully-victims were at increased risk of young adult depression (OR, 4.8; 95% CI, 1.2–19.4, p <0.05), panic disorder (OR, 14.5; 95% CI, 5.7–36.6, p <0.001), agoraphobia (females only; OR, 26.7; 95% CI, 4.3–52.5, p <0.001), and suicidality (males only: OR, 18.5; 95% CI, 6.2–55.1, p <0.0001). Bullies were at risk for antisocial personality disorder only (OR, 4.1; 95% CI, 1.1–15.8, p < 0.04).

Conclusion

The effects of being bullied are direct, pleiotropic and long- lasting with the worst effects for those who are both victims and bullies.

Introduction

Research on bullying can be traced to the 1960s, then called mobbing and described as collective aggression against others of the same species1. Systematic intervention research started when three young boys killed themselves in short succession in Norway, all leaving notes that they had been bullied by their peers2. Since then it has been repeatedly reported that being a victim of bullying increases the risk of adverse outcomes including physical health problems3, behavior and emotional problems and depression4, and psychotic symptoms5 and poor school achievement6. Furthermore, being bullied is associated with increased risk of suicide ideation and attempts7 with some evidence that those who are both victims and bully others, so called bully-victims8 are at higher risk for suicidality9. In contrast, the major adverse outcome of being a bully in childhood has been reported to be offending10,11. Bullying is, however, still commonly viewed as just a harmless rite of passage or an inevitable part of growing up12.

Longitudinal studies on bullying involvement as victims or bully-victims have tended to be short term, ranging from a few months to following children a few years into adolescence4. Thus, it is unclear whether the effects of being bullied extend into adulthood. To date, one Finnish cohort study has reported on involvement in bullying at 8 years of age and adult outcomes, using information from the military call-up registry, national psychiatric register13, self-report of depression and suicide ideation14, National Police crime records13, Finnish hospital discharge register15 or cause of death registry16. Male frequent victimization in childhood was found to predict adult anxiety disorders, frequent bullying antisocial personality disorder and male bully-victims were reported at increased risk for both anxiety and antisocial personality disorder. However, most male bully-victims (97%), male bullies (80%) and 50% of male victims also screened positive for behavioral problems at the age of 8 years13. Thus, once behavioral or emotional problems in childhood were accounted for, effects of bullying involvement became non-significant in males. In contrast to boys, girls were rarely victimized (3.6%) and very rarely frequently bullied others (0.6%) or frequent bully-victims (0.2%)13, but female victims remained at higher risk for psychopathology and suicidality15,16 even after controlling for childhood emotional problems. This suggests that for girls peer victimization may be more traumatic. Peer victimization in childhood may be a marker of present and later psychopathology rather than a cause of long term adverse outcomes17, at least in boys. The Finnish study relied on registry data in adulthood but only a minority of those with psychiatric problems are recognized in the health system18.

This study investigates the long term effects of bullying involvement in childhood and adolescence on self-reported psychiatric outcomes in young adulthood including suicidality. We expected victims to suffer more often emotional problems, bully-victims additionally to be at risk for suicidality and bullies at risk for antisocial personality disorder. Sex differences are tested to determine possible differential susceptibility as previously suggested. Both childhood and adolescent bullying involvement and young adulthood psychiatric outcomes were assessed using structured interviews administered multiple times in in a large community sample.

Methods

Participants

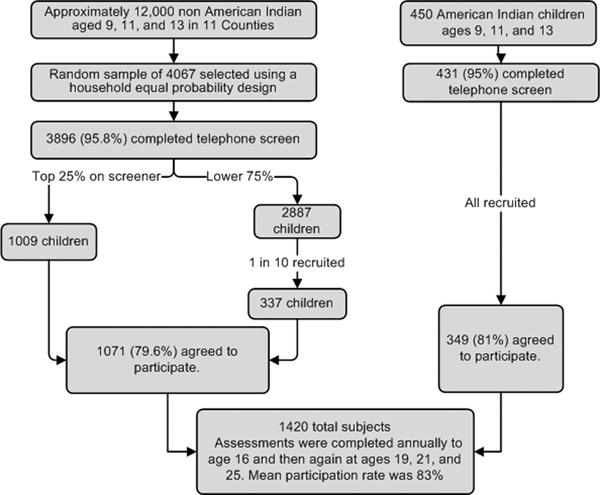

The Great Smoky Mountain Study is a population-based sample of three cohorts of children, age 9, 11, and 13 at intake, recruited from 11 counties in Western North Carolina in 1993 using a multi-stage household equal probability, accelerated cohort design (see figure 1)19. Each age cohort reaches a given age in a different year, reducing the time needed to study effects of age. The first stage involved screening parents (N=3,896) for child behavior problems. All non-American Indian children scoring in the top 25% on a behavioral problems screener, plus a 1-in-10 random sample of the rest, were recruited for detailed interviews. All subjects were given a weight inversely proportional to their probability of selection, so that the results are representative of the population from which the sample was drawn. This means that screen-high subjects are weighted down and randomly-selected subjects are weighted up so that oversampling does not bias prevalence estimates. About 8% of the area residents and the sample are African American, and fewer than 1% are Hispanic. American Indians make up only about 3% of the study area but were recruited regardless of screen score to constitute 25% of the sample. Of all subjects recruited, 80% (N=1420) agreed to participate. The weighted sample was 49.0% female.

Figure 1.

Ascertainment strategy for the Great Smoky Mountain Study

Procedure

Annual assessments were completed with the child and the primary caregiver until age 16 and then with the participant again at ages 19, 21, and 24–26 years (completed in 2010). 6674 assessments were completed on 1420 subjects in childhood (ages 9 to 16) and 3184 assessments in young adulthood (ages 19, 21, and 24–26). An average of 83% of possible interviews was completed overall (range: 75% to 94%). Before interviews, participants signed informed consent forms approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Assessment of Bullying

At each assessment between ages 9 and 16, the child and their parent reported on whether the child had been bullied/teased or bullied others in the 3 months immediately prior to the interview as part of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA)20(full definitions provided in table 1). Being bullied or bullying others was counted if reported by either the parent or the child at any childhood or adolescent assessment. If the informant reported that the subject had been bullied or bullied others, then the informant was asked separately how often the bullying occurred in the prior 3 months in the following three settings: home, school, and the community. Parent and child agreement (kappa=0.24) was similar to that of other bullying measures5. Although this may seem low, a large meta-analysis of parent and self-report of behavioral and emotional functioning report similar concordance levels21. All subjects were categorized as victims only, bullies only, both (bully-victims) or neither.

Table 1.

Definitions and interview probes for Bullying and Being Bullied

| Variable | How assessed? | How often? | Definition | Interview Questions* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being bullied/teased | Structured interview with the child and their parent | 4 to 6 times between ages 9 and 16 | Child is a particular object of mockery, physical attacks or threats by peers or siblings. |

Do you get teased or bullied at all by your siblings or friends/peers?

Is that more than other children? Are other boys and girls mean to you? |

| Bullying | Structured interview with the child and their parent | 4 to 6 times between ages 9 and 16 | Child engages in deliberate actions aimed at causing distress to another or attempts to force another to do something against his/her will by using threats, violence, or intimidation. |

Do you ever do things to upset other people on purpose or try to hurt them on purpose?

Do you ever try to get other people into trouble on purpose? Have you ever forced someone to do something s/he didn't want to do by threatening or hurting him/her? Do you ever pick on anyone? |

Interviewer begins with standard questions, but may ask additional questions to ensure that the definition is met in full. Furthermore, interviewer asks who the perpetrator was (sibling or peers). Only peer bullying coded for this study. Frequency within the past 3 months and onset of bullying involvement were also assessed.

Assessment of Adult Outcomes

Outcome status was positive if subject met criteria for a psychiatric disorder at age 19, 21, or 24–26. All outcomes were assessed through self-report interviews with the Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment (YAPA)20. The timeframe for the YAPA was the 3 months immediately preceding the interview. Scoring programs, written in SAS22, combined information about the date of onset, duration, and intensity of each symptom to create diagnoses according to the DSM-IV23. Two-week test-retest reliability of the YAPA is comparable to that of other highly structured interviews (kappas for individual disorders range from .56 to 1.0)24. Validity is well-established using multiple indices of construct validity20. The YAPA interview itself, the YAPA glossary, and all diagnostic codebooks are available at http://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/instruments.html.

Diagnoses made included any DSM-IV anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety, agoraphobia, panic disorder, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder), depressive disorders (major depression, minor depression, and dysthymia), antisocial personality disorder, alcohol abuse/dependence, and marijuana abuse/dependence. Psychosis was not included in analyses as it was very rare in the community. Suicidality was assessed as part of the criteria for major depressive episode25. Suicidality involves either recurrent thoughts of wanting to die, recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, suicidal plans or a suicide attempt. Too few subjects attempted suicide (N=5) for us to study this group separately from ideation. As such, the focus of this analysis was on the broader construct of suicidality rather than the individual aspects of suicidality.

Assessment of Childhood Status

All childhood psychiatric and family hardships variables (except where indicated) were assessed by parent and self-report using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA)20. The timeframe for the CAPA was the 3 months immediately preceding the interview.

Childhood psychiatric variables included the same anxiety and depressive disorders as in adulthood, behavioral disorders (conduct disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder) and any substance abuse or dependence. Subjects were positive for a diagnosis if they met full DSM-IV criteria for the disorder at any childhood assessment. Childhood suicidality was assessed as it was during young adulthood.

Four types of family hardships were assessed: low socioeconomic status (SES), unstable family structure, family dysfunction, and maltreatment. Low SES was positive if the child's family met 2 or more of the following conditions: below the US federal poverty line based upon family size and income, parental high school education only, or low parental occupational prestige26. Unstable family structure was positive if child's family met 2 or more of the following conditions: single parent structure, step-parent in household, divorce, parental separation, or change in parent structure. Family dysfunction was positive if child's family met 5 or more of the following conditions: inadequate parental supervision of child's free time, over-involvement of the parent into the child's activities in an age-inappropriate manner, physical violence between parents, top 20% in terms of frequency of parental arguments, marital relationship characterized by absence of affection, apathy, or indifference, child is upset by or actively involved in arguments between parents, mother scores in elevated range on depression questionnaire, top 20% in terms of frequency of arguments between parent and child, and most parental activities are source of tension or worry for the child. Maltreatment was positive if child or parent reported that the child had been physically abused (subject victim of intentional physical violence by family member), sexually abused (subject involved in activities for purposes of perpetrators sexual gratification including kissing, fondling, oral-genital, oral-anal, genital or anal intercourse), or neglected by parents (caregiver unable to meet child's need for food, clothing, housing, transportation, medical attention or safety). Codebooks for all items available at http://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/codebooks.html.

Statistical Analyses

Multiple assessments were completed in childhood (ages 9 to 16) and young adulthood (ages 19, 21, and 25). Status for all variables were aggregated across assessments within these periods. Thus, if an individual reported suicidality at any young adult assessment, they were positive for suicidality in adulthood. All associations were tested using weighted logistic regression models in a generalized estimating equations framework implemented by SAS PROC GENMOD. Robust variance (sandwich type) estimates were used to adjust the standard errors of the parameter estimates for the sampling weights applied to observations. Bivariate analyses in tables 2 and 3 involved prediction of outcome variables by dummy-coded variables comparing each bully/victim group to in the neither group. Multivariable analyses in table 4 involved prediction of young adult outcome variables by bully/victim status but also included childhood psychiatric variables and hardships as covariates. As such, these models test the effect of bully/victim status on later psychiatric outcomes after statistically accounting for the effects of early psychiatric problems and hardships. Finally, a sex by bully/victim status interaction term was included in multivariable models to test for sex-specific long-term effects. Odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p values are provided for all analyses.

Table 2.

Associations between bully/victim groups and young adult psychiatric outcomes.

| Neither N=789 | Bully only N=100 | Victim only N=305 | Bully/Victim N=79 | Victim vs. Neither | Bully-victim vs. Neither | Bully vs. Neither | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | |

| Depressive Disorders | 3.3 | 5.0 | 10.2 | 21.5 | 3.4 (1.5–7.9) | 0.004 | 8.2 (2.6–25.5) | <0.001 | 1.6 (0.6–4.1) | 0.36 |

| Suicidality | 5.7 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 24.8 | 1.6 (0.7–4.0) | 0.29 | 5.5 (1.7–17.4) | 0.004 | 0.3 (0.1–1.2) | 0.10 |

| Anxiety Disorders | 6.3 | 12.5 | 24.2 | 32.2 | 4.7 (2.5–9.1) | <0.001 | 7.1 (2.6–18.8) | <0.001 | 2.1 (0.7–6.3) | 0.18 |

| Generalized Anxiety | 3.1 | 9.1 | 10.2 | 13.6 | 3.6 (1.4–9.3) | 0.008 | 5.0 (1.4–18.5) | 0.02 | 3.2 (0.8–13.5) | 0.11 |

| Panic | 4.6 | 5.8 | 13.1 | 38.4 | 3.2 (1.5–6.7) | 0.002 | 13.1 (5.0–34.1) | <0.001 | 1.3 (0.5–3.2) | 0.56 |

| Agoraphobia | 2.3 | 2.7 | 11.1 | 10.3 | 5.3 (2.0–13.9) | <0.001 | 4.9 (1.0–23.6) | 0.04 | 1.2 (0.3–4.2) | 0.78 |

| Antisocial Personality | 2.1 | 9.4 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 0.06 | 1.3 (0.3–5.3) | 0.74 | 4.9 (1.0–23.3) | 0.04 |

| Alcohol disorders | 16.4 | 29.0 | 15.6 | 22.9 | 1.0 (0.5–1.7) | 0.83 | 1.5 (0.6–4.1) | 0.41 | 2.1 (0.9–4.8) | 0.09 |

| –Marijuana disorder | 15.9 | 24.8 | 14.7 | 16.1 | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.77 | 1.0 (0.4–2.9) | 0.97 | 1.8 (0.8–4.0) | 0.19 |

Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05.THC=Marijuana-related. OR = odds ratio; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval.

Table 3.

Associations between bully/victim groups and childhood psychiatric and family hardships.

| Neither N=789 | Bully only N=100 | Victim only N=305 | Bully/Victim N=79 | Victim vs. Neither | Bully-victim vs. Neither | Bully vs. Neither | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | |

| Child Psychiatric | ||||||||||

| Depressive Disorders | 5.7 | 13.0 | 8.1 | 31.3 | 1.5 (0.7–3.0) | 0.30 | 7.6 (3.0–18.8) | <0.001 | 2.5 (0.9–6.8) | 0.08 |

| Suicidality | 10.6 | 14.7 | 21.5 | 22.7 | 2.3 (1.3–4.0) | 0.003 | 2.5 (1.1–5.7) | 0.03 | 1.5(0.8–2.8) | 0.26 |

| Anxiety Disorders | 5.9 | 13.7 | 16.7 | 19.7 | 3.2 (1.7–6.0) | <0.001 | 3.9 (1.7–9.0) | 0.001 | 2.5 (0.9–7.0) | 0.07 |

| Disruptive disorders | 8.0 | 60.7 | 16.3 | 88.3 | 2.2 (1.4–3.7) | 0.002 | 87.0 (28.1–269.2) | <0.001 | 17.8 (8.3–38.0) | <0.001 |

| Substance disorders | 6.9 | 24.9 | 9.3 | 28.0 | 1.4 (0.6–3.0) | 0.41 | 5.3 (2.1–13.3) | <0.001 | 4.5 (2.0–10.3) | <0.001 |

| Social/family | ||||||||||

| Low SES | 39.9 | 51.2 | 40.5 | 46.1 | 1.6 (1.0–2.4) | 0.03 | 2.0 (0.9–4.3) | 0.08 | 2.5 (1.2–4.9) | 0.01 |

| Family instability | 23.5 | 39.5 | 28.8 | 42.0 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 0.23 | 2.3(1.1–5.2) | 0.03 | 2.1 (1.1–4.4) | 0.04 |

| Family dysfunction | 19.6 | 54.6 | 37.7 | 56.9 | 2.5 (1.6–3.9) | <0.001 | 5.4 (2.5–12.0) | <0.001 | 4.9 (2.5–9.9) | <0.001 |

| Maltreatment | 15.1 | 43.3 | 26.5 | 49.4 | 2.0 (1.3–3.2) | 0.003 | 5.5 (2.5–12.0) | <0.001 | 4.3 (2.1–8.8) | <0.001 |

Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05.OR = odds ratio; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval.

Table 4.

Associations between bully/victim groups and young adult psychiatric outcomes accounting for childhood psychiatric and family hardships.

| Victim vs. Neither | Bully-victim vs. Neither | Bully vs. Neither | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p value | Sig. Covariates | OR (95%CI) | p value | Sig. Covariates | OR (95%CI) | p value | Sig. Covariates | |

| Depressive Disorders | 2.3 (0.8–6.2) | 0.11 | 1,4 | 4.8 (1.2–19.4) | 0.03 | 1,2,4,9 | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) | 0.51 | 1,2,7,8 |

| Suicidality | 1.2 (0.4–3.3) | 0.78 | 2 | F: 0.6 (0.1–3.9) M: 18.5 (6.2–55.1) |

0.56 <0.001 |

5 7 |

0.4 (0.1–1.7) | 0.21 | 1,2,7,8 |

| Anxiety Disorders | 4.3 (2.1–8.6) | <0.001 | 1,8 | 2.3 (0.7–7.3) | 0.17 | 6,9 | 1.1 (0.4–3.0) | 0.80 | 5,6,9 |

| Generalized Anxiety | 2.7 (1.1–6.3) | 0.02 | 1,4,8,9,10 | F: 1.8 (0.3–11.3) M: 0.4 (0.1–2.4) |

0.54 0.34 |

6,9 3,10 |

1.1 (0.3–3.9) | 0.83 | 5,6,8,9 |

| Panic | 3.1 (1.5–6.5) | 0.003 | 1 | 14.5 (5.7–36.6) | <0.001 | 1 | 1.6 (0.5–4.8) | 0.44 | 1,7 |

| Agoraphobia | 4.6 (1.7–12.5) | 0.003 | 2,4,7,9,10 |

F: 26.7 (4.3–52.5) M: 0.8(0.1–10.6) |

<0.001 0.85 |

7 9 |

1.9 (0.5–6.9) | 0.32 | 7 |

| Antisocial Personality | 0.3 (0.1–1.4) | 0.11 | 1,4 | 2.4 (0.5–9.3) | 0.22 | 1,3,4 | 4.1 (1.1–15.8) | 0.04 | 1,3,4 |

| Alcohol disorders | F: 2.6(0.5–12.4) M: 0.6(0.3–1.2) |

0.12 0.12 |

1 7,10 |

0.7 (0.2–2.6) | 0.62 | `1,4,10 | 1.5 (0.6–3.3) | 0.38 | 1,2,10 |

| Marijuana disorder | F: 3.1 (0.9–10.0) M: 0.5(0.3–1.2) |

0.06 0.11 |

4,8 10 |

0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 0.06 | 1,10 | 1.2 (0.5–2.7) | 0.71 | 1,6,10 |

Covariates that predicted the young adult psychiatric outcome variable significantly. Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05. Childhood psychiatric and family hardships and other covariates: 1=Sex; 2 = Low SES; 3 = Family instability; 4 = Family dysfunction; 5 = Maltreatment; 6 = Depressive disorders; 7 = Suicidality; 8 = anxiety disorders; 9 = Disruptive disorders; 10 = Substance disorders. If there was a significant sex by bully status interaction, results are presented separately for males and females.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Four hundred twenty-one child or adolescent participants (26.1%: all percentages weighted) reported being bullied during at least once; 8.9% (N=159) reported being bullied more than once. Rates were not higher in boys (28.8% vs. 23.4%, p=0.15). Being bullied was twice as common in childhood (9 to 13) as in adolescence (14–16) (23.5% vs. 10.2%, p < 0.001).

Bullying others was reported by 9.5% (N=198) and was more common among victims of bullying (OR=2.9, 95%CI=2.0–4.1, p<0.001). Independent groups were derived based upon bullying and victim status: 5.0% (N=112) were bullies only, 21.6% (N=335) were victims only, 4.5% (N=86) were both bullies and victims (bully-victims), and 68.9% (N=887) were neither. Further analyses are based upon these groups. Compared to the neither group, both bully-victims and bullies were more likely to be male, but victim status did not differ by sex (bully-victims: 72.4% male vs. 47.8%, p<0.01; bullies: 69.1% male vs. 47.8%, p<0.05; and victims: 52.9% male vs. 47.8%, p=0.34).

Adult outcomes

Of the 1420 subjects assessed in childhood, 1273 or 89.7% were followed up in young adulthood. Follow-up rates were similar across bully/victim groups (bullies: 100 of 112 or 89.3%; victims: 305 of 335 or 91.0%; bully-victims: 79 of 86 or 91.9%; neither: 789 of 887 or 89.0%) with no differences between the follow-up rate between the neither group and any of the three bully/victim groups (neither vs. bullies, p = 0.39; neither vs. victims, p = 0.95; neither vs. bullies, p = 0.93).

Both groups of victims were at risk for young adult psychiatric disorders, compared with those with no history of bullying or being bullied (Table 2). Columns 2 to 5 show the rates of young adult psychiatric outcomes by childhood bully/victim status. The remaining columns compare the odds for each of the bully/victim groups with the odds of those that were neither bullied nor bullied others. Those who were only victims had higher levels of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, generalized anxiety, panic disorder, and agoraphobia, whereas bully-victims had higher levels of all anxiety and depressive disorders. Bully-victims also had the highest levels of suicidality with 24.8% reporting suicidality in young adulthood as compared to 5.7% of those in the neither group. Bully-victims also reported the highest levels of depressive disorders (21.5% vs. 3.3% in neither group), generalized anxiety (13.6% vs. 3.1%), and panic 38.4% vs. 4.6%). Bullies were at increased risk for antisocial personality disorder with 9.4% meeting full criteria in young adulthood as compared to 2.1% in the neither group. None of the groups had elevated levels of substance disorders as compared to those that had not been bullied or bullied others.

Childhood psychiatric and family hardships

Table 3 shows the relations between group status and childhood psychiatric diagnoses and family hardships. These factors may have occurred either before or after the child was first bullied or first bullied others. The findings are consistent with previous research in suggesting widespread psychiatric problems and social/family hardships for victims and bully-victims12. Bullies looked similar to bully-victims with high levels of disruptive behavior disorders and family hardships, but they were not significantly elevated for emotional disorders. Suicidality was higher in childhood for all victim groups.

Long-term Outcomes after adjustment for childhood factors

We tested whether the adverse long-term psychiatric outcomes observed were direct effects or better accounted for by childhood psychiatric and family hardships. All models were also tested for differences by sex.

The results of the multivariable models are provided in Table 4. Victims of bullying continued to be at risk for all anxiety disorders in models adjusted for childhood psychiatric status and hardships, but the association with depressive disorders was attenuated and no longer statistically significant. There were sex differences in victims risk for substance disorders although the increased risk for female victims in both cases fell below common statistical thresholds. Bully-victims continued to be at significant risk for depressive disorders, and panic disorder after inclusion of covariates. There was also evidence of sex-specific risk with males at 18.5 higher odds for suicidality and females at 26.7 times the odds for agoraphobia as compared to the “neither” group. The risk for generalized anxiety and overall anxiety disorders were no longer significant for bully-victims. As in the unadjusted models, bullies were not at increased risk for either anxiety or depressive disorders, but they continued to be at risk for antisocial personality disorder. Across all adjusted models, childhood psychiatric variables and hardships were associated with later psychiatric problems.

The models in table 4 were adjusted for childhood psychiatric status and hardships at any point in childhood or adolescence. As such, these covariates could be confounders of the association between bully/victim status and later psychiatric problems if they occurred prior to being bullied or bullying others or potential mediators if they occurred subsequent to being bullied or bullying others. To provide a robust test of confounding, all models in table 4 were rerun including only psychiatric disorder and family hardships that had occurred prior to being bullied or bullying others. This reanalysis did not change the pattern of finding from table 4 in any way.

The repeated assessments of bullying involvement across childhood and adolescence allowed us to address the issue of chronicity. Were the long-term effects worse for those that had been involved in bullying either as a bully, victim, or both at multiple timepoints? To test this, we limited the analysis to those that had participated in at least 3 observations in childhood or adolescence (N=1180) and then tested a continuous measure of the total number of assessments with bullying involvement as opposed to the dichotomous variable used previously. Across all groups, a substantial percentage (>25%) of individuals reported involvement at multiple assessments. All adjusted models in table 4 were retested. In terms of statistical significance, results mirrored those previously obtained with 2 exceptions: Female victims risk for marijuana disorder was significant (p =0.04) and bully-victims risk for depressive disorders fell below the common significance threshold (p =0.06). There were similar results if repeated involvement was defined as occurring in both childhood (ages 9 to 13) and adolescence (ages 14 to 16).

Comment

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore prospectively the association between peer victimization in childhood and adult psychiatric diagnoses and suicidality. Victims of bullying in childhood were at increased risk of anxiety disorders in adulthood, and those who were both victims and perpetrators were at increased risk of adult depression and panic disorder. Female bully-victims were at risk for agoraphobia and male bully-victims were at increased risk for suicidality. These effects were maintained even after accounting for preexisting psychiatric problems or family hardships. This suggests that the effects of victimization by peers on long-term adverse psychiatric outcomes are not confounded by other childhood factors. Although deviant in childhood, bullies were only at risk for antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.

Victims and bully-victims differed from children not involved in bullying in their family background and in their childhood psychological functioning. This is consistent with profiles found in other studies, where victims are described as withdrawn, unassertive, easily emotionally upset, and as having poor emotion or social understanding27, whereas bully-victims tend to be aggressive, easily angered, and frequently bullied by their siblings12, 28. As such, bully-victims have few friends who would stand up for them; they are the henchman or reinforcers for the bullies and the most troubled children29,30.

This pattern has been interpreted to suggest that victimization occurs within a context of other risk factors and may not be causal in predicting later outcomes in and of itself. This hypothesis has received some support in the only previous child to adulthood study of bullying17 where the risk for psychiatric hospitalization or depression 5–15 years later in frequent victims and bully-victims was eradicated for boys and attenuated for girls after controlling for prior psychopathology15. Suicidal ideation was the primary outcome where there was some evidence of unattenuated direct effects of victimization16 but again only for girls. The Finnish study, however, relied upon questionnaires completed at one time point, or on registries, while the current study used structured interviews administered multiple times in young adulthood. In this study, the long-term effects were maintained even after accounting for all common childhood psychiatric disorders and a range of family hardships and were generally similar for male and female victims or bullies. Contrary to the previous Finnish study, we did not find girls more often traumatized by bullying13,14 rather both males and females are equally adversely affected by peer victimization. Similarly, both male and female bully-victims were at highly increased risk for depression. This provides strong evidence that being a victim of bullying or being both a victim and a perpetrator is a risk factor for serious emotional problems for both males and females independent of preexisting problems. However, only male bully-victims reported more often suicidality while females suffered more often agoraphobia in early adulthood indicating different tendencies by the sexes of dealing with distress caused by being a bully-victim. Furthermore, being a bully increases the risk of antisocial personality disorder over and above disruptive behavior disorder in childhood or family hardship. A recent meta-analysis supports that bullying perpetration increases the risk of later offending11. This study adds that the risk of antisocial personality disorder is increased in both males and female bullies but not in those who both bully and become victims.

How does being victimized lead to emotional disorders and suicidality? This may occur by altering the physiological response to stress, affecting telomere length or the epigenome, by interacting with a genetic vulnerability to emotional disorders or by changing cognitive responses to threatening situations. For example, victimization has been found to alter HPA-axis activity31 and altered cortisol response are associated with increased risk for developing depression32 Recently, erosion of the length of telomeres, the repetitive TTAGGG sequence at the end of linear chromosomes, has emerged as a promising new biomarker of stress. Accelerated erosion has been found in children if exposed to violence such as bullying, domestic violence or physical maltreatment33. Evidence for gene-environment interaction by variation in the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene of children exposed to bullying victimization for emotional problems has also been demonstrated34. Furthermore, peer rejection has been repeatedly reported to lead to negative emotional reaction and depending on depression status to avoidant coping behavior35. Each of these aspects of stress response should be targets for future research efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the present study are 1) the prospective study design with repeated assessments during childhood/adolescence and early adulthood, 2) the use of multiple informants for a combined measure of peer victimization, 3) a population-based design that minimized selection biases, and 4) availability of information on a variety of social/family factors and pre- or concurrent psychiatric disorders to control for confounding. Finally, the prevalence rates of peer victimization are similar to those reported in other similar studies36. Not all subjects were interviewed at every assessment, but response rate have remained high (>80%) over almost 20 years, and there was no evidence of selective dropout for victims or bullies. The current sample is representative of children from the area sampled, but not of children in the US. The focus of this analysis was bullying in the school setting, but bullying also occurs at home and in the community. It is not clear if bullying in other settings has similar long-term effects37. Furthermore, we had overall assessment of bullying and could not distinguish between overt and relational bullying which may affect males and females differently38. Finally, this study provides strong evidence of the effects of bullying on suicidality in general, but is unable to parse effects on specific aspects of suicidality (e.g., attempts) due to the rarity of these behaviors in this community sample.

Conclusion

Bullying is not just a harmless rite of passage or an inevitable part of growing up. Victims of bullying are at increased risk for emotional disorders in adulthood. Bully-victims are at highest risk and are most likely to think about or plan suicide. These problems are associated with great emotional and financial costs to society7. Bullying can be easily assessed and monitored by health professionals and school personnel and effective interventions that reduce victimization are available39. Such interventions are likely to reduce human suffering and long term health costs and provide a safer environment for children to grow up in.

Acknowledgements

The work presented here was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH63970, MH63671, MH48085), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA/MH11301), NARSAD (Early Career Award to First Author), and the William T Grant Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures None of the authors have biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Copeland had full access to all the data in the study, performed all statistical analyses, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Lorenz K. On Aggression. Methuen & Co; London: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stassen Berger K. Update on bullying at school: Science forgotten? Developmental Review. 2007;27(1):90–126. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gini G, Pozzoli T. Association Between Bullying and Psychosomatic Problems: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2009 Mar 1;123(3):1059–1065. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1215. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(4):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreier A, Wolke D, Thomas K, Horwood J, Hollis C, Gunnell D, Lewis G, Thompson A, Zammit S, Duffy L, Salvi G, Harrison G. Prospective Study of Peer Victimization in Childhood and Psychotic Symptoms in a Nonclinical Population at Age 12 Years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 May 1;66(5):527–536. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.23. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamoto J, Schwartz D. Is Peer Victimization Associated with Academic Achievement? A Meta-analytic Review. Social Development. 2010;19(2):221–242. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunstein Klomek A, Sourander A, Gould MS. The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: a review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;55(5):282–288. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y, Leventhal B. Bullying and suicide: A review. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008;20(2):133–154. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2008.20.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winsper C, Lereya T, Zanarini M, Wolke D. Involvement in Bullying and Suicide-Related Behavior at 11 Years: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(3):271–282.e273. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrington DP, Ttofi MM, Lösel F. School bullying and later criminal offending. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2011;21(2):77–79. doi: 10.1002/cbm.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, Lösel F, Loeber R. The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: A systematic/meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2011;21(2):80–89. doi: 10.1002/cbm.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: “Much ado about nothing”? Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(5):717–729. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sourander A, Jensen P, Ronning JA, Niemela S, Helenius H, Sillanmaki L, Kumpulainen K, Piha J, Tamminen T, Moilanen I, Almqvist F. What Is the Early Adulthood Outcome of Boys Who Bully or Are Bullied in Childhood? The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” Study. Pediatrics. 2007 Aug 1;120(2):397–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2704. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anat Brunstein K, Andre S, Kirsti K, Jorma P, Tuula T, Irma M, Fredrik A, Madelyn SG. Childhood bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidal ideation among Finnish males. Journal of affective disorders. 2008;109(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.226. 07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sourander A, Ronning J, Brunstein-Klomek A, Gyllenberg D, Kumpulainen K, Niemela S, Helenius H, Sillanmaki L, Ristkari T, Tamminen T, Moilanen I, Piha J, Almqvist F. Childhood Bullying Behavior and Later Psychiatric Hospital and Psychopharmacologic Treatment: Findings From the Finnish 1981 Birth Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Sep 1;66(9):1005–1012. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.122. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klomek AB, Sourander A, Niemelä S, Kumpulainen K, Piha J, Tamminen T, Almqvist F, Gould MS. Childhood Bullying Behaviors as a Risk for Suicide Attempts and Completed Suicides: A Population-Based Birth Cohort Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(3):254–261. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318196b91f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rønning J, Sourander A, Kumpulainen K, Tamminen T, Niemelä S, Moilanen I, Helenius H, Piha J, Almqvist F. Cross-informant agreement about bullying and victimization among eight-year-olds: whose information best predicts psychiatric caseness 10–15 years later? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44(1):15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sourander A, Haavisto A, Ronning JA, Multimaki P, Parkkola K, Santalahti P, Nikolakaros G, Helenius H, Moilanen I, Tamminen T, Piha J, Kumpulainen K, Almqvist F. Recognition of psychiatric disorders, and self-perceived problems. A follow-up study from age 8 to age 18. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;46(10):1124–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns B, Stangl D, Tweed D, Erkanli A, Worthman C. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: Goals, designs, methods, and the prevalence of DSMIII-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angold A, Costello E. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SAS/STAT® Software: Version 9 [computer program] Version SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fourth Edition Text Revision. American Psychiatric Press; Washington D.C: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angold A, Costello EJ. A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPAC) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:755–762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakao K, Treas J. The 1989 Socioeconomic Index of Occupations: Construction from the 1989 Occupational Prestige Scores,”. National Opinion Research Center; Chicago, Illinois: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woods S, Wolke D, Novicki S, Hall L. Emotion recognition abilities and empathy of victims of bullying. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(5):307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monks CP, Smith PK, Naylor P, Barter C, Ireland JL, Coyne I. Bullying in different contexts: Commonalities, differences and the role of theory. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2009;14(2):146–156. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salmivalli C. Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2010;15(2):112–120. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juvonen J, Graham S, Schuster MA. Bullying Among Young Adolescents: The Strong, the Weak, and the Troubled. Pediatrics. 2003 Dec 1;112(6):1231–1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouellet-Morin I, Danese A, Bowes L, Shakoor S, Ambler A, Pariante CM, Papadopoulos AS, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L. A Discordant Monozygotic Twin Design Shows Blunted Cortisol Reactivity Among Bullied Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(6):574–582.e573. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harkness KL, Stewart JG, Wynne-Edwards KE. Cortisol reactivity to social stress in adolescents: Role of depression severity and child maltreatment. Psychoneuroendocrino. 2011;36(2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shalev I, Moffitt TE, Sugden K, Williams B, Houts RM, Danese A, Mill J, Arseneault L, Caspi A. Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: a longitudinal study. Mol Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugden K, Arseneault L, Harrington HL, Moffitt TE, Williams B, Caspi A. Serotonin Transporter Gene Moderates the Development of Emotional Problems Among Children Following Bullying Victimization. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reijntjes A, Stegge H, Terwogt M, Kamphuis J, Telch M. Children's coping with in vivo peer rejection: An experimental investigation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(6):873–885. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klomek AB, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Bullying, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;46(1):40–49. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242237.84925.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolke D, Skew AJ. Bullying among siblings. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2012;24(1) doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2012.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crick N, Ostrov J, Werner N. A Longitudinal Study of Relational Aggression, Physical Aggression, and Children's Social–Psychological Adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(2):127–138. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. J. Exp. Criminol. 2011 Mar;7(1):27–56. [Google Scholar]