Abstract

Background

Acute otitis media (AOM) occurs as a complication of viral upper respiratory tract infections in young children. AOM and respiratory viruses both display seasonal variation. Our objective was to examine the temporal association between circulating respiratory viruses and the occurrence of pediatric ambulatory care visits for AOM.

Methods

This retrospective study included 9 seasons of respiratory viral activity (2002-2010) in Utah. We used Intermountain Healthcare's electronic medical records to assess community respiratory viral activity via laboratory-based active surveillance and to identify children <18 years with outpatient visits and ICD-9 codes for AOM. We assessed the strength of the association between AOM and individual respiratory viruses using interrupted time series analyses.

Results

During the study period, 96,418 respiratory viral tests were performed; 46,460 (48%) were positive. The most commonly identified viruses were: RSV (22%), rhinovirus (8%), influenza (8%), parainfluenza (4%), human metapneumovirus (3%), and adenovirus (3%). AOM was diagnosed during 271,268 ambulatory visits. There were significant associations between peak activity of RSV, human metapneumovirus, influenza A, and office visits for AOM. Adenovirus, parainfluenza, and rhinovirus were not associated with visits for AOM.

Conclusions

Seasonal RSV, human metapneumovirus, and influenza activity were temporally associated with increased diagnoses of AOM among children. These findings support the role of individual respiratory viruses in the development AOM. These data also underscore the potential for respiratory viral vaccines to reduce the burden of AOM.

Keywords: respiratory tract infection, influenza, RSV, human metapneumovirus, pediatrics

Background

Acute upper respiratory tract infections are one of the most common reasons for medical encounters and hospitalizations during childhood.1,2 More than 60% of upper respiratory tract infection episodes are complicated by acute otitis media (AOM); a common reason for outpatient healthcare visits and antibiotic prescribing in children.3 Previous studies using culture techniques reported isolation of respiratory viruses among children with AOM and demonstrated a significantly higher risk for development of AOM following infection by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza virus.4-6 Molecular diagnostic methods have enhanced our ability to detect established and emerging pathogens (e.g. human metapneumovirus) responsible for respiratory tract infections and have further established the importance of respiratory viruses in pediatric respiratory infections and AOM.7,8

Understanding the role of respiratory viruses and the development of AOM is challenging, as individual viruses may differ in middle ear tropism and in their ability to cause viral or bacterial middle ear infections.9 However, improved understanding of which respiratory viruses are most closely associated with the development of AOM may be useful in the clinical evaluation of children with upper respiratory tract infections and in the development of viral vaccines for AOM prevention. Our objective was to examine the strength of the association between new and established respiratory viruses and AOM using data from a large healthcare system.

Materials and Methods

Human Subject Protection

This study was approved and granted a waiver of informed consent by the University of Utah and Intermountain Healthcare (Intermountain) Institutional Review Boards.

Setting and Study Population

We performed a retrospective study of respiratory viral activity from January 2002 through December 2010 (9 years) in Utah using the Intermountain system. Intermountain is a large vertically-integrated non-profit healthcare system that owns and operates 22 hospitals and more than 100 ambulatory care clinics in Utah and southern Idaho, including Primary Children's Medical Center (PCMC), a tertiary Children's hospital in Salt Lake City, UT.

We evaluated associations between respiratory viral activity among children younger than 18 years and ambulatory care visits for AOM, as defined below. We analyzed cases of AOM for all Utah-resident children who received care at an Intermountain facility. Although marketshare data for outpatient visits were not available, approximately 75-85% of all pediatric hospitalizations for Utah residents occurred at Intermountain facilities and this proportion remained stable throughout the study period (courtesy of Jim Bradshaw, Director of Strategic Planning, Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, UT).

Respiratory Viral Testing

Testing for adenovirus, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, and 3, and RSV has been performed using direct fluorescent antibody (DFA), enzyme immunoassay (EIA), and viral culture in the Intermountain system since 2001. Testing for human metapneumovirus by DFA and rhinovirus by PCR began in 2006 and 2007, respectively. From 2002 through 2008, DFA-negative specimens were submitted for viral culture. Beginning in 2009, DFA-negative samples were submitted for multiplex PCR testing (Luminex xTAG Respiratory Virus Panel; Luminex Diagnostics, Austin, Texas). This PCR-based assay detects adenovirus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza 1-3, RSV, human metapneumovirus, and rhinovirus. Respiratory samples (e.g., nasopharyngeal aspirates) were obtained primarily from children with respiratory symptoms in emergency department and inpatient settings. Respiratory specimens were tested for the purposes of isolation, cohorting, and medical treatment. In addition, at PCMC respiratory viral testing was recommended for all febrile infants younger than 90 days of age from 2005 and for all Intermountain facilities from 2008.

Identification of Acute Otitis Media

In 2004, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published a clinical practice guideline defining the diagnosis of AOM as signs of middle-ear effusion, signs and symptoms of middle-ear inflammation, and confirmation of acute onset.10 For this study, AOM was defined based on billing codes using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes. All Intermountain facilities share an electronic records system that includes demographic, clinical, microbiologic, and financial data. We queried the system for cases of AOM among Utah children younger than 18 years at all Intermountain facilities over 9 years. AOM-specific ICD-9 codes included 381 (acute non-suppurative, serous, mucoid, and sanguinous otitis media) and 382 (acute suppurative otitis media with and without spontaneous rupture of the eardrum), as previously described by Zhou et al.11

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the absolute number of ICD-9 coded AOM episodes and the frequency of individual respiratory viruses identified in Utah throughout the Intermountain system. These data were tabulated in 1-week increments for statistical analyses. We calculated the proportion of positive tests by dividing the number of individual viruses identified each week by the number of viral tests performed.

Correlations between each respiratory virus and AOM were explored by Spearman rank correlations. With the goal of controlling for the auto-correlation of time series data, we used methods developed by Box and Jenkins to build an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) time series model.12 To account for the seasonal and periodical patterns of AOM and individual respiratory viruses, we modeled the difference – or change – from one week to the next, rather than modeling the series itself. The final model also compared the lag time between the detection of respiratory viruses and the date of ICD-9 coded AOM diagnosis at 0, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Identification of Viral Respiratory Tract Infections

From January 2002 through December 2010, 46,460 (48%) of 96,418 unique respiratory samples submitted for viral testing were positive (Table 1). The respiratory viruses detected showed winter seasonality (Fig., Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/B415).

Table 1.

Frequency of respiratory viral detection by testing period.

| Respiratory Virus | Jan 2002 – Nov 2006 | Dec 2006 – Oct 2007 | Nov 2007 – Dec 2010 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSV | 9579 (26%) | 1934 (21%) | 9815 (19%) | 21328 (22%) |

| Influenza A | 1344 (4%) | 340 (4%) | 5261 (10%) | 6945 (7%) |

| Influenza B | 339 (1%) | 120 (1%) | 448 (1%) | 907 (1%) |

| Parainfluenza | 1709 (5%) | 435 (5%) | 1893 (4%) | 4037 (4%) |

| Adenovirus | 999 (3%) | 309 (3%) | 1603 (3%) | 2911 (3%) |

| Human metapneumovirus* | -- | 436 (5%) | 2385 (5%) | 2821 (3%) |

| Rhinovirus** | -- | -- | 7511 (15%) | 7511 (8%) |

| Negative | 22646 (62%) | 5537 (62%) | 21775 (43%) | 49958 (52%) |

Human metapneumovirus testing began in November 2006.

Rhinovirus testing began in November 2007.

Seasonality of Viral Respiratory Tract Infections

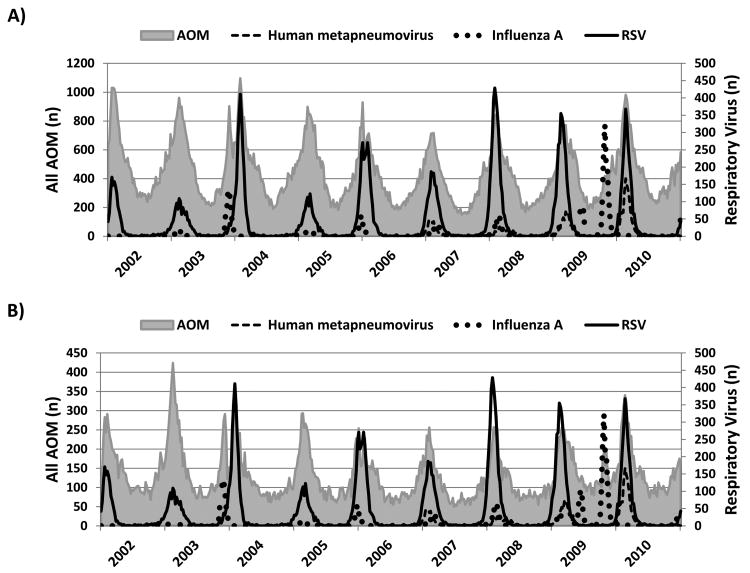

The seasonal patterns of circulating respiratory viruses are shown in Figure 1 and Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/B416. RSV, influenza, and human metapneumovirus showed distinctive and variable winter peaks. Ninety-eight percent of positive RSV and 93% of positive human metapneumovirus detections occurred between November and April. The seasonality was somewhat different for influenza, with only 56% of detections occurring between these months. This was due to two waves of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in May and September of 2009. With the exception of the 2003-2004 and 2009-2010 seasons, peak RSV, influenza, and human metapneumovirus activity overlapped to variable degrees. The seasonality of adenovirus, rhinovirus, and parainfluenza was less pronounced (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/B416).

Figure 1.

Weekly relationship between ICD-9 coded acute otitis media (AOM) and human metapneumovirus, influenza A, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) by age group: A) children 0-4 years and B) children 5-17 years of age.

Note: The dual influenza A peaks in 2009 correspond to the Spring and Fall waves of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

Seasonality of ICD-9 Coded Acute Otitis Media

During the study period 271,268 children residing in Utah were diagnosed with AOM at an Intermountain facility. There was an average of 30,141 AOM diagnoses per year, with the largest number (34,934) occurring during the 2003-2004 season. AOM diagnoses exhibited moderate seasonality, with 66% of visits identified between November and April of each year. The majority of AOM visits (77%) were among children younger than 5 years of age.

Correlations between Acute Otitis Media and Circulating Respiratory Viruses

There were strong correlations observed between AOM visits at Intermountain facilities and the activity of individual circulating respiratory viruses. AOM visits were strongly correlated with the isolation of RSV (r=0.87; P<0.001) and human metapneumovirus (r=0.79, P<0.001). We found statistically significant but weaker correlations between AOM and influenza A (r=0.53; P<0.001), influenza B (r=0.43; P<0.001), adenovirus (r=0.40; P<0.001), and rhinovirus (r=0.38; P<0.001). The correlation with AOM at time lags of 2, 4, and 8 weeks although weaker, remained significant. When first-order auto-regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models were constructed that appropriately corrected for the autocorrelation of our time-series data, the association was no longer statistically significant for a number of respiratory viruses (Table 2). However, RSV and human metapneumovirus both remained significantly associated with AOM at 2 weeks (P<0.001) and 4 weeks (P<0.001), and the strongest association was observed at lag times of 8 weeks (P<0.001) and 7 weeks (P<0.001), respectively. The strength and timing of these associations were similar among children <5 years and those 5-17 years of age.

Table 2.

Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) analysis for circulating respiratory viruses and acute otitis media.

| Respiratory Virus | Lag Time | < 5 years (P-value) | 5 – 17 years (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | No lag | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| 1-week lag | 0.20 | 0.75 | |

| 2-week lag | 0.94 | 0.30 | |

| 4-week lag | 0.43 | 0.01 | |

| 8-week lag | 0.46 | 0.36 | |

| Influenza B | No lag | 0.33 | 0.69 |

| 1-week lag | 0.34 | 0.43 | |

| 2-week lag | 0.99 | 0.24 | |

| 4-week lag | 0.37 | 0.81 | |

| 8-week lag | 0.04 | 0.10 | |

| RSV | No lag | 0.65 | 0.27 |

| 1-week lag | 0.18 | 0.91 | |

| 2-week lag | 0.01 | 0.28 | |

| 4-week lag | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| 8-week lag | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Human metapneumovirus | No lag | 0.41 | 0.92 |

| 1-week lag | 0.27 | 0.38 | |

| 2-week lag | 0.07 | 0.17 | |

| 4-week lag | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| 8-week lag | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Adenovirus | No lag | 0.48 | 0.39 |

| 1-week lag | 0.16 | 0.66 | |

| 2-week lag | 0.65 | 0.88 | |

| 4-week lag | 0.32 | 0.51 | |

| 8-week lag | 0.13 | 0.30 | |

| Parainfluenza | No lag | 0.50 | 0.69 |

| 1-week lag | 0.47 | 0.83 | |

| 2-week lag | 0.59 | 0.99 | |

| 4-week lag | 0.37 | 0.24 | |

| 8-week lag | 0.34 | 0.58 | |

| Rhinovirus | No lag | 0.84 | 0.78 |

| 1-week lag | 0.86 | 0.83 | |

| 2-week lag | 0.56 | 0.66 | |

| 4-week lag | 0.29 | 0.68 | |

| 8-week lag | 0.30 | 0.41 |

A weaker association was found with influenza A, which varied by age. Among children younger than 5 years, the association between influenza A and AOM was strongest without a lag (P=0.04). However, among children 5-17 years of age the strongest associations were found at 3 weeks (P=0.02) and 4 weeks (P=0.009). A weak association was also observed for influenza B at 8 weeks (P=0.04). Adenovirus, parainfluenza, and rhinovirus were not associated with AOM visits when modeled at time 0 or with lag times up to 8 weeks.

Discussion

Respiratory viral infections have long-been implicated in the pathogenesis of AOM. However, the contribution and influence of specific respiratory viruses to the development of AOM is not well understood. In this population-based ecologic study, we demonstrated temporal associations between RSV, human metapneumovirus, and influenza activity in a large healthcare system with AOM, as measured by ICD-9 coding of AOM clinic discharges. In contrast, we did not observe an association between adenovirus, parainfluenza, or rhinovirus activity and health care visits for AOM.

AOM is the most common cause of health care visits among children in the United States. More than 70% of children have experienced at least one episode of AOM by 2 years of age.13 In the United States, direct and indirect medical expenditures for AOM-related healthcare visits and antibiotic prescriptions are estimated to be $3.5 billion in this age group.11,14 AOM is often regarded as a bacterial infection and is the primary indication for more than 10 million antibiotic prescriptions annually among children younger than 18 years.2 Bacteria have been identified in 50-90% of middle ear fluid samples from children with AOM.15,16 However, newer molecular detection methods have increased the detection of respiratory viruses—alone and in combination with bacteria in the middle ear fluid of children with AOM.17 Ruohola et al18 evaluated the etiology of AOM among children with tympanostomy tubes and identified viruses in 70% of cases. Moreover, they detected viral and bacterial co-infections in 66% of children with AOM.

The risk of developing AOM following a viral upper respiratory tract infection appears to vary by virus, but assessing the contribution of individual respiratory viruses has been difficult, primarily due to differences in methodologies. Ruusaken et al6, using respiratory viral antigen testing of nasopharyngeal specimens, noted a significant correlation between AOM and RSV. In this study, AOM developed in 57% of children with RSV infection, compared with 35% with influenza A infection, with lower rates for other respiratory viruses. In another study, Henderson et al4, testing nasopharyngeal specimens by viral culture, reported a strong association between RSV, influenza A and B, adenovirus and parainfluenza with AOM, with AOM developing in 33% of RSV positive children. Moreover, they found that rhinovirus outbreaks either preceded or coincided with peaks in AOM diagnoses.

In our study, using a combination of antigen detection, viral culture, and PCR for respiratory viral detection, we found results that are similar in several ways to previous studies.4,6 We observed a strong temporal association between AOM and RSV activity. In addition, the effects of RSV were also prolonged with a lag period extending past 8 weeks. We also noted a significant association between AOM and influenza virus, similar to previous studies.4-6 In our dataset, the effect of influenza on AOM varied by age. There was no lag between influenza A activity and AOM among young children (<5 years), but the association began at 4 weeks in older children (≥ 5 years old). We do not believe that this lag reflects the risk of developing AOM among individuals; rather, it may reflect the epidemiologic impact of respiratory viruses at the population level. The reason for this differential effect of influenza on AOM is unknown, and needs further investigation.

Our study is one of the first to demonstrate a strong and prolonged association between AOM and human metapneumovirus, with the best fit achieved using lag periods from 4 weeks to more than 8 weeks. The strength of this association was comparable to that of RSV. The role of human metapneumovirus in AOM has not been well defined. Boivin et al19 reported that approximately 50% of patients admitted for human metapneumovirus infection displayed “otitis” symptoms. Using PCR, Williams et al20 evaluated viral culture-negative nasal wash and middle ear fluid specimens from children with AOM and detected human metapneumovirus in 6% of nasal wash samples. In another study by Nokso-Koivisto et al21, AOM developed in 24% of children with confirmed human metapneumovirus upper respiratory tract infection. Our finding of a strong temporal association between human metapneumovirus and AOM supports the role of human metapneumovirus in the etiology of AOM.

Contrary to earlier reports, we did not observe an association between AOM and rhinovirus, adenovirus, or parainfluenza activity.3,6,17 This may be the result of our use of ARIMA models, which assess changes in activity compared to the previous week rather than the absolute number of cases. This method is powerful as it does not disregard the stochastic dependence of consecutive measurements. For example, a high burden of respiratory viral activity today tends to predict high activity the next day (positive auto-correlation). ARIMA models are useful for discriminating between natural seasonal patterns and true associations.22 However, the transformation of data to a stationary series through differencing has the potential to underestimate a true association with viruses which display milder seasonal fluctuations, such as rhinovirus.23

Although temporal association does not prove a causal relationship, many lines of evidence suggest a direct role for respiratory viruses in the pathogenesis of AOM. Animal studies have demonstrated synergism between respiratory viral infections and AOM in chinchillas following intranasal inoculation with influenza A virus, S. pneumoniae, or both pathogens.24 In humans, many studies have demonstrated the presence of respiratory viruses in the MEF of children with AOM by antigen detection, culture, or nucleic acid detection. Furthermore the testing of MEF and nasopharyngeal specimens by PCR has detected viruses that were infrequently detected by other methods.25 As a result, rhinovirus, other picornaviruses, human metapneumovirus, and coronavirus have increasingly been detected from MEF and nasopharyngeal specimens of children with AOM.3,21 However, prolonged nasopharyngeal shedding of rhinovirus, enterovirus, bocavirus, and adenovirus26-28 in both symptomatic29 and asymptomatic30 children limits the ability to determine the significance of the detection of these viruses in AOM. This may explain, in part, the absence of an epidemiologic correlation between rhinovirus, adenovirus and parainfluenza and AOM in this study.

Several studies have shown clear benefits of influenza vaccines in preventing AOM, with reductions of AOM of 30% to 83% among vaccine recipients.31-33 Utah influenza immunization coverage was 49.2% (±7.3%) in 2010-2011 among children 6 months to 17 years of age, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) National Immunization Survey.34 These data suggest that more effective immunization strategies have the potential to decrease the burden of influenza-associated AOM. In a study on the prevention of RSV infection by passive immune prophylaxis, intravenous RSV-immune globulin administered to premature infants decreased the incidence of AOM by 80%.35 Passive antibody therapy is too expensive to have a major impact on the burden of AOM, but vaccines for RSV are under development.36 Moreover, preliminary studies of the antigenic epitopes of human metapneumovirus may lead to the development of human metapneumovirus vaccines.37

This study is subject to several limitations. First, this study was not designed to demonstrate a causal relationship between individual respiratory viruses and the development of AOM. Therefore, the temporal associations we observed must be further investigated by clinical studies at the patient level. It is unclear why the lag time between respiratory viral activity and AOM diagnoses differed by age group. Second, it is possible that viral testing may have been more likely to be ordered for subjects who complained of earaches, as opposed to those who reported generalized viral symptoms. Third, because respiratory viral testing was primarily performed among inpatients and those presenting to emergency departments our findings may not reflect the association between respiratory viruses, including rhinoviruses, and AOM in the outpatient setting. Fourth, we could not assess the immunization status of the children included in this study. Vaccine coverage for influenza and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines rose throughout the study period and were comparable to national rates. The rates measured by the CDC's 2011 National Immunization (influenza 49.2% and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 80.1%) were comparable to national rates.34,38 Fifth, we could not account for environmental factors such as pollution, humidity, temperature, and rainfall, which may represent potential confounding factors.39 Sixth, newly described respiratory viruses including non-SARS coronaviruses and bocavirus were not evaluated. Seventh, our study was based in a single geographic region and thus our findings may not be generalizable. Lastly, the use of ICD-9 discharge codes may lead to misclassification, potentially incorrectly ascribing cases of AOM. We were unable to independently assess the presence of the AAP's diagnostic criteria among our cohort of patients;10 however, ICD-9 coded AOM has been reported to be in 94% agreement with manual review of the medical record.40

AOM is the most common bacterial infection and the most frequent indication for antibiotic therapy in young children, with substantial clinical and economic impact. Therefore, efforts to prevent AOM are desperately needed. Our study provides evidence of strong temporal relationships between AOM visits among children and RSV, human metapneumovirus, and influenza activity. We speculate that a meaningful reduction in the overall incidence of AOM could be accomplished by the effective control of RSV, human metapneumovirus, and influenza.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [grant number U01A1082482] (to KA, CLB), [grant number U01 AI074419-01] (to CLB, ATP), [grant number U01AI082184-01] (to ATP), the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, (UL1RR025764) to CLB and the Centers for Disease Control Prevention [U18-IP000303-01] (to CS, KA, CLB, ATP). This project was further supported by the University of Utah, Department of Pediatrics through the Children's Health Research Center and the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Scholars Program, the H. A. and Edna Benning Presidential Endowment, and the Primary Children's Medical Center Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Previous Presentations: Presented in part at the Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting; April 28, 2012; Boston, Massachusetts.

Contributor's Statement: Multiple contributors were required to complete this study. Each author has seen and approved the final manuscript that is being submitted.

Mr. Stockmann had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Chris Stockmann, MSc: assisted with development of the study design, conducted statistical analyses of the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Krow Ampofo, MD: provided pivotal input to the study design, helped write the manuscript, and critically edited the final submission.

Adam L. Hersh, MD, PhD: assisted with study design, selection of appropriate statistical tests, and edited the manuscript.

Scott T. Carleton, MD: assisted with study design and edited the manuscript.

Kent Korgenski, MS, MT(ASCP): identified patients in Intermountain Healthcare's electronic data records, developed the database for performing statistical analyses, and edited the manuscript.

Xiaoming Sheng, PhD: assisted Chris Stockmann with the statistical analyses and development of the ARIMA model. Dr. Sheng also edited the manuscript.

Andrew T. Pavia, MD: participated in the conception of the study design and interpretation of the data, critically reviewed and revised the content of the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published.

Carrie L. Byington, MD: supervised the development of the study design, provided input on the statistical analyses, helped write the manuscript, and approved the final product.

References

- 1.Christensen KL, Holman RC, Steiner CA, Sejvar JJ, Stoll BJ, Schonberger LB. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009;49:1025–35. doi: 10.1086/605562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Shah SS. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1053–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chonmaitree T, Revai K, Grady JJ, et al. Viral upper respiratory tract infection and otitis media complication in young children. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008;46:815–23. doi: 10.1086/528685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson FW, Collier AM, Sanyal MA, et al. A longitudinal study of respiratory viruses and bacteria in the etiology of acute otitis media with effusion. The New England journal of medicine. 1982;306:1377–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198206103062301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chonmaitree T, Howie VM, Truant AL. Presence of respiratory viruses in middle ear fluids and nasal wash specimens from children with acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 1986;77:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruuskanen O, Arola M, Putto-Laurila A, et al. Acute otitis media and respiratory virus infections. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1989;8:94–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams JV, Harris PA, Tollefson SJ, et al. Human metapneumovirus and lower respiratory tract disease in otherwise healthy infants and children. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:443–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, et al. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nature medicine. 2001;7:719–24. doi: 10.1038/89098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heikkinen T. Role of viruses in the pathogenesis of acute otitis media. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2000;19:S17–22. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200005001-00004. discussion S-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis M. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1451–65. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou F, Shefer A, Kong Y, Nuorti JP. Trends in acute otitis media-related health care utilization by privately insured young children in the United States, 1997-2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121:253–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Box GEP, Jenkins GM, Reinsel GC. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teele DW, Klein JO, Rosner B. Epidemiology of otitis media during the first seven years of life in children in greater Boston: a prospective, cohort study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1989;160:83–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stool SE, Field MJ. The impact of otitis media. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1989;8:S11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Beccaro MA, Mendelman PM, Inglis AF, et al. Bacteriology of acute otitis media: a new perspective. The Journal of pediatrics. 1992;120:81–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilpi T, Herva E, Kaijalainen T, Syrjanen R, Takala AK. Bacteriology of acute otitis media in a cohort of Finnish children followed for the first two years of life. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2001;20:654–62. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heikkinen T, Thint M, Chonmaitree T. Prevalence of various respiratory viruses in the middle ear during acute otitis media. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;340:260–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901283400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruohola A, Meurman O, Nikkari S, et al. Microbiology of acute otitis media in children with tympanostomy tubes: prevalences of bacteria and viruses. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006;43:1417–22. doi: 10.1086/509332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boivin G, De Serres G, Cote S, et al. Human metapneumovirus infections in hospitalized children. Emerging infectious diseases. 2003;9:634–40. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.030017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams JV, Tollefson SJ, Nair S, Chonmaitree T. Association of human metapneumovirus with acute otitis media. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2006;70:1189–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nokso-Koivisto J, Pyles RB, Miller AL, Patel JA, Loeffelholz M, Chonmaitree T. Viral load and acute otitis media development after human metapneumovirus upper respiratory tract infection. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2012;31:763–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182539d92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helfenstein U. Box-Jenkins Modelling in Medical Research. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1996;5:3–22. doi: 10.1177/096228029600500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helfenstein U. Detecting hidden relations between time series of mortality rates. Methods of information in medicine. 1990;29:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giebink GS, Berzins IK, Marker SC, Schiffman G. Experimental otitis media after nasal inoculation of Streptococcus pneumoniae and influenza A virus in chinchillas. Infection and immunity. 1980;30:445–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.2.445-450.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettigrew MM, Gent JF, Pyles RB, Miller AL, Nokso-Koivisto J, Chonmaitree T. Viral-bacterial interactions and risk of acute otitis media complicating upper respiratory tract infection. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2011;49:3750–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01186-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalu SU, Loeffelholz M, Beck E, et al. Persistence of adenovirus nucleic acids in nasopharyngeal secretions: a diagnostic conundrum. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2010;29:746–50. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d743c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin ET, Fairchok MP, Kuypers J, et al. Frequent and prolonged shedding of bocavirus in young children attending daycare. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;201:1625–32. doi: 10.1086/652405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jartti T, Lehtinen P, Vuorinen T, Koskenvuo M, Ruuskanen O. Persistence of rhinovirus and enterovirus RNA after acute respiratory illness in children. Journal of medical virology. 2004;72:695–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winther B, Alper CM, Mandel EM, Doyle WJ, Hendley JO. Temporal relationships between colds, upper respiratory viruses detected by polymerase chain reaction, and otitis media in young children followed through a typical cold season. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1069–75. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Zalm MM, van Ewijk BE, Wilbrink B, Uiterwaal CS, Wolfs TF, van der Ent CK. Respiratory pathogens in children with and without respiratory symptoms. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009;154:396–400. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heikkinen T, Ruuskanen O, Waris M, Ziegler T, Arola M, Halonen P. Influenza vaccination in the prevention of acute otitis media in children. American journal of diseases of children. 1991;145:445–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160040103017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoberman A, Greenberg DP, Paradise JL, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccine in preventing acute otitis media in young children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:1608–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchisio P, Cavagna R, Maspes B, et al. Efficacy of intranasal virosomal influenza vaccine in the prevention of recurrent acute otitis media in children. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002;35:168–74. doi: 10.1086/341028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Interim results: state-specific influenza vaccination coverage--United States, August 2010-February 2011. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2011;60:737–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simoes EA, Groothuis JR, Tristram DA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-enriched globulin for the prevention of acute otitis media in high risk children. The Journal of pediatrics. 1996;129:214–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurwitz JL. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccine development. Expert review of vaccines. 2011;10:1415–33. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen X, Krause JC, Leser GP, et al. Structure of the human metapneumovirus fusion protein with neutralizing antibody identifies a pneumovirus antigenic site. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012;19:461–3. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Statistics and Surveillance: 2011 Table Data. [Accessed 03 November 2012];Immunization Coverage in the US. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nis/data/tables_2011.htm.

- 39.Zemek R, Szyszkowicz M, Rowe BH. Air pollution and emergency department visits for otitis media: a case-crossover study in Edmonton, Canada. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118:1631–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorelick MH, Knight S, Alessandrini EA, et al. Lack of agreement in pediatric emergency department discharge diagnoses from clinical and administrative data sources. Academic emergency medicine: official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007;14:646–52. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.03.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.