Abstract

The activation of cellular signal transduction pathways by solar ultraviolet (SUV) irradiation plays a vital role in skin tumorigenesis. Although many pathways have been studied using pure ultraviolet A (UVA) or ultraviolet B (UVB) irradiation, the signaling pathways induced by SUV (i.e., sunlight) are not understood well enough to permit improvements for prevention, prognosis and treatment. Here we report parallel protein kinase array studies aimed at determining the dominant signaling pathway involved in SUV irradiation. Our results indicated that the p38-related signal transduction pathway was dramatically affected by SUV irradiation. SUV (60 kJ UVA/m2/3.6 kJ UVB/m2) irradiation stimulates phosphorylation of p38α (MAPK14) by 5.78-fold, MSK2 (RPS6KA4) by 6.38-fold and HSP27 (HSPB1) by 34.56-fold compared to untreated controls. By investigating the tumorigenic role of SUV-induced signal transduction in wildtype and p38 dominant negative (p38 DN) mice, we found that p38 blockade yielded fewer and smaller tumors. These results establish that p38 signaling is critical for SUV-induced skin carcinogenesis.

Keywords: solar UV, p38, signal transduction pathway, skin cancer

Introduction

Each year, over one million Americans are diagnosed with skin cancer, including 68,000 cases of melanoma (http://www.Cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/skin). Epidemiological evidence suggests that solar ultraviolet (SUV, i.e., sunlight) irradiation is the most important risk factor for any type of skin cancer (1–2). SUV comprises approximately 95% UVA and 5% UVB. Both UVA and UVB can cause DNA damage (3), which is considered one etiologic factor contributing to the development of skin cancer. UV irradiation can cause DNA lesions, such as DNA cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (4). Consequently, many gene mutations have been identified in skin cancer, including mutations in p53, ptch and ras (5–6). These gene mutations and related signal pathway activation are known to contribute to skin carcinogenesis (7–8). Activation of UV-induced cellular signaling pathways plays a vital role in UV-induced skin tumorigenesis (9). UVB can activate PKC, ATM, Akt, ERKs, JNKs and p38 (9–14). UVA also can activate Akt, ERKs and JNKs in HaCaT or JB6 cells (15–16). Consequently, these kinases activate their downstream transcription factors, such as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) (17). These transcription factor families are heavily involved in many cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation and survival. Based on these results, inhibitors of these kinases, such as norathyriol (an ERKs inhibitor) (18), kaempferol (a Src and RSK2 inhibitor) (14), luteolin (a PKC inhibitor) (19), caffeic acid (a Fyn inhibitor) have been suggested for UV-induced skin cancer chemoprevention (20).

Although UV activation of signal transduction pathways and their role in tumorigenesis have been intensively examined, differences in SUV-, UVA-, or UVB-induced signal transduction pathways have not been fully investigated (21). Furthermore, the primary signal transduction pathway and key molecules involved in SUV-induced tumorigenesis are not yet completely elucidated. Answers to these questions will contribute to a better understanding of UV-induced skin carcinogenesis and development of new strategies for skin cancer prevention.

Here, we first used phospho-protein kinase array analysis to identify the potential signaling pathways induced by SUV irradiation. The results indicated that the p38-related signal transduction pathway was markedly affected by SUV treatment. To investigate the role of p38 in SUV-induced tumorigenesis, wildtype and p38 dominant negative (DN) mice were utilized. Our results indicated that compared with wildtype control mice, p38 DN mice exhibited fewer and smaller tumors when exposed to chronic SUV. In conclusion, our results indicated that p38 signaling plays an important role in SUV-induced skin carcinogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Chemical reagents, including Tris, NaCl, and SDS, for molecular biology and buffer preparation, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies for Western blot analysis were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA), R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) or Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The Human Phospho-Kinase and Human Phospho-MAPK Arrays were obtained from R&D Systems.

Solar UV, UVB and UVA irradiation systems

The solar UV resource was UVA-340 lamps purchased from Q-Lab Corporation (Cleveland, OH). The UVA-340 lamps provide the best possible simulation of sunlight in the critical short wavelength region from 365 nm down to the solar cutoff of 295 nm with a peak emission of 340 nm (22). The percentage of UVA and UVB of UVA-340 lamps was measured by a UV meter and was 94.5% and 5.5% respectively. UVB irradiation was performed in a chamber with a transluminator emitting UVB light protons and fitted with an Eastman Kodak Co. Kodacel K6808 filter to eliminate all wavelengths below 290 nm (23). The UVA source was a Philips TL100w/10R system from Ultraviolet Resources International (Lakewood, OH). UVA irradiation was filtered through 6 mm of plate glass, eliminating UVC and UVB light below 320 nm (16).

Cell culture and UV irradiation

Normal human skin keratinocytes, N/TERT-1 and N/TERT-2G, cells were generously provided by Dr. James G Rheinwald (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). These cells were cytogenetically tested and authenticated before being frozen. Each vial of frozen cells was thawed and maintained in culture for a maximum of 8 weeks. Enough frozen vials were available to ensure that all cell-based experiments were completed. N/TERT-1 and N/TERT-2G cells are hTERT immortalized human keratinocyte cell lines derived from different batches of the same cell line. They still maintain the ability to differentiate (24). N/TERT-1 and N/TERT-2G cells were maintained at low density in keratinocyte serum-free media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 0.2 ng/mL EGF, 0.4 mM Ca2+, 25 µg/mL BPE, 5 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. When 90% confluent, cells were starved for 24 h with F-12K medium without serum and then irradiated with UVA, UVB or SUV in the same medium. The cells were harvested and proteins visualized by Western blotting or protein kinase array.

Western blotting analysis

For Western blotting, cells (1×106) were cultured in 10-cm dishes for 24 h. The cells were then cultured with F-12K medium without serum for 24 h and then treated with various doses of UVA, UVB or SUV in the same medium. The protein concentration was determined and lysate proteins (30 µg) were subjected to 10% SDS/PAGE. After transferring proteins, membranes were incubated with a specific primary antibody at 4°C overnight. Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Amersham, UK) after hybridization with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody.

Protein kinase array analysis

Analysis of phosphorylated proteins by human phospho-MAPK and human phospho-kinase arrays was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cell lysates (500 µg) were collected and incubated with each array at 4 °C overnight on a rocking platform shaker. The cell lysate was removed the next day and arrays were washed 3 times with washing buffer. Arrays were incubated with the primary antibody solution for 2 h at room temperature and washed 3 times with washing buffer. The second antibody solution was added to the array and incubated on a rocking shaker for another 1 h. The array was washed 3 times with washing buffer and protein spots were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection kit. The density of the each duplicated array spot was assessed using the Image J computer program (v.1.37v, NIH) and the density was calculated by subtracting the background and PBS negative control. The fold change was obtained by comparing SUV-treated samples with the untreated control (indicated as a value of 1).

SUV-induced skin carcinogenesis

Skin carcinogenesis in mice was induced using UVA-340 lamps (Q-Lab Corporation, Cleveland, OH). SKH-1-p38 Wt and SKH-1-p38 DN hairless mice were developed and provided by Dr. G. Tim Bowden (University of Arizona Cancer Center, Tucson, AZ) and propagated and maintained at The Hormel Institute. Mice were maintained under conditions based on the guidelines established by Research Animal Resources, University of Minnesota. The wildtype and transgenic mice were identified by PCR (Supplementary Figure 1) using the K14 forward primer (5-AAG CAG TCG CAT CCC TTT CC-3) and reverse primer (5-ACA GGT TCT GGT ATC GTT C-3). The mice were divided into 4 groups of 20 animals each (6 wk old, with an average body weight of 25 g). For untreated control groups, SKH-1-p38 Wt and SKH-1-p38 DN mice were not irradiated with SUV. For the experimental SUV-treated groups, SKH-1-p38 Wt and SKH-1-p38 DN mice were initially treated with an SUV dose of 30 kJ UVA/m2/1.8 kJ UVB/m2 twice a week. The dose was increased by10% each week until week 6. At week 6, the dose reached 48 kJ UVA/m2 /2.9 kJ UVB/m2 and this dose was maintained from weeks 6 to 15. At 15 weeks, SUV exposure was discontinued and tumor growth was monitored an additional 15 weeks. A tumor was defined as an outgrowth of > 1 mm in diameter that persisted for 2 weeks or more. Tumor numbers and volume were recorded every week until the end of the experiment. One-half of the samples were immediately fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunostaining. The other half was frozen for Western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are expressed as means ± S.E. or S.D. as indicated. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. A probability of p < 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

SUV activates JNKs in a time- and dose-dependent manner

JNKs activation is an indicator of cellular stress and JNKs-induced phosphorylation of the transcription factor c-Jun and the subsequent expression of c-Jun-induced genes mediate JNKs-induced apoptosis (25). Previously, we reported that JNKs were activated by both UVA and UVB (26–27) and therefore, we first determined whether SUV could also induce JNKs activation. To examine the dose and the time point at which SUV might stimulate a response in normal keratinocytes, we chose a TERT-immortalized normal human keratinocyte line (N/TERT-1) and treated the cells with different doses of SUV and examined the phosphorylation of JNKs and their downstream target, c-Jun. The results indicated that the phosphorylation of JNKs was increased at a dose of 60 kJ UVA/m2/3.6 kJ UVB/m2 (Fig. 1A, upper panel). The UVB output in SUV was similar to the output of pure UVB that has been reported to stimulate JNKs activation in other cell types (19). Higher doses (90 kJ UVA/m2/5.4 kJ UVB/m2) caused the cells to undergo apoptosis within 3 h. We thus determined the optimal time point after exposure to SUV (60 kJ UVA/m2/3.6 kJ UVB/m2) at which JNKs were clearly activated and cells maintained a healthy condition. Results indicated that JNKs and downstream c-Jun could be activated as early as 15 min after SUV irradiation and sustained up to 4 h at which time, the phosphorylation level began to decreas (Fig. 1A, lower panel). To determine whether this dose and time point were similar in other keratinocyte lines, we subjected N/TERT-2G cells to the same dose and time course of SUV and observed the JNKs activation pattern to be similar in both N/TERT-2G and N/TERT-1 cells (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. SUV irradiation activates JNKs in normal human skin keratinocytes.

(A) N/TERT-1 cells (1×106) were cultured in a 10-cm dish for 24 h. The cells were then incubated with F-12K medium without serum for 24 h and then treated with SUV as indicated. Cell lysates (30 µg) were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection kit after hybridization with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. (B) A second normal human keratinocyte N/TERT-2G cell line was used to examine SUV-induced JNKs activation under the same conditions as for N/TERT-1 cells.

p38α activation is the dominant SUV-induced signaling transduction pathway

MAPKs play an important role in UV-induced skin cancer (28). To identify the major MAPK pathway induced by SUV in keratinocytes, we performed a parallel phospho-MAPK array assay on cells treated with SUV, UVA, or UVB irradiation. The doses of UVA and UVB were the same UV doses observed in SUV. Before the MAPK array assay, we determined the cellular response to UVA, UVB and SUV irradiation. UVB (3.6 kJ/m2) or SUV (60 kJ UVA/m2/3.6 kJ UVB/m2), but not UVA, could activate JNKs (Fig. 2A, upper panel). Interestingly, we found that ERKs phosphorylation (T202/Y204) was decreased after UVA, UVB, or SUV treatment (Fig. 2A, upper panel). We then used the same cell lysates to perform a phospho-MAPK array assay. The results indicated that SUV induced increased phosphorylation of p38α by 5.78-fold, MSK2 by 6.38-fold and HSP27 by 34.56-fold compared to the untreated control. The pattern induced by SUV was similar to the induction by UVB. Phosphorylation of p38α increased 5.88-fold, MSK2 7.65-fold and HSP27 20.67-fold. In contrast, induction by UVA was weaker in that phosphorylation of p38α increased 1.71-fold, MSK2 0.86-fold and HSP27 3.44-fold. Phosphorylation of JNKs was also increased by 2.08-fold after SUV treatment (Fig. 2A, B). Consistent with the Western blot results, the array results indicated that phosphorylation of ERKs (T202/Y204) was decreased, along with its downstream kinases RSK1 (Ser 380) and RSK2 (Ser 386). The phosphorylation pattern of the various p38 isoforms, including p38β, p38γ, p38δ, was not as clear as the phosphorylation of p38 α after SUV irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The p38α-related signaling pathway is strongly activated by UVB or SUV irradiation.

(A) N/TERT-1 cells were cultured with keratinocyte-sfm medium and starved for 24 h. The cells were irradiated with UVA (60 kJ/m2), UVB (3.6 kJ/ m2) or SUV (60 kJ UVA/m2/3.6 kJ UVB/m2). At 30 min after irradiation, the cells were harvested and phosphorylation of JNKs was determined by Western blot analysis. Protein extracts (500 µg) were used for phospho-MAP kinase array analysis. Array spots were visualized using an ECL kit. (B) The density of the each duplicated array spot in A was measured as described in Methods and Materials. The graph shows the fold change in SUV-induced phosphorylation of JNKs, ERKs, p38, MSK, and HSP27 compared to untreated control (i.e., value of 1). Data are shown as an average of duplicate samples.

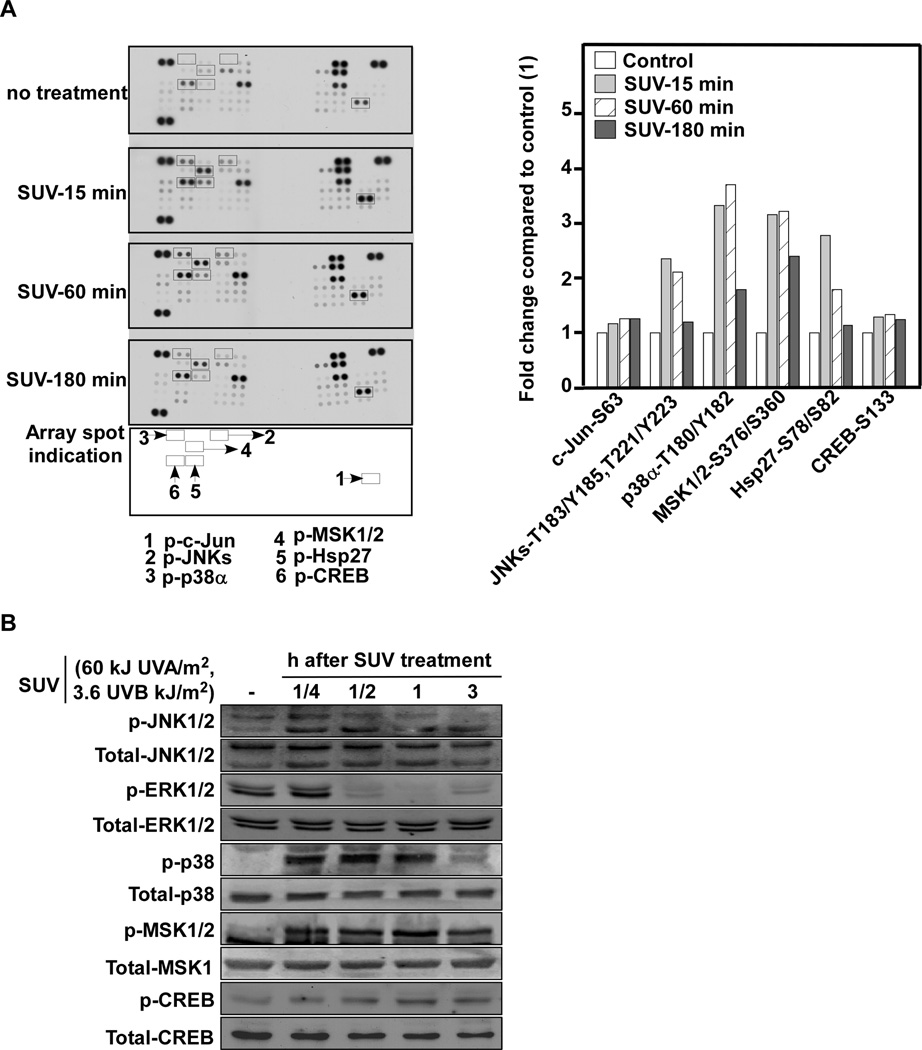

Solar UV activates the p38α-signaling pathway in a time-dependent manner

To further identify the primary signal transduction pathway induced by SUV, UVA or UVB, we used a human phospho-kinase array comprising 46 kinases, including the kinases from the phospho-MAPK array. The results indicated that SUV increased phosphorylation of p38α by 2.53-fold, MSK1/2 by 3.67-fold, CREB by 2.67-fold, and HSP27 by 3.36-fold compared to control. Similarly, UVB increased phosphorylation of p38α by 2.36-fold, MSK1/2 by 3.97- fold, CREB by 2.40-fold, and HSP27 by 2.54-fold. In contrast, UVA had little effect (e.g., p38α = 1.01-fold, MSK2 = 1.00-fold, CREB = 1.22-fold and HSP27 = 0.91-fold; Fig. 3A, B). To determine whether the phospho-MAPK array and phospho-kinase array data are reliable, we used the same cell lysates for Western blot analysis. SUV and UVB, but not UVA, could strongly activate p38, MSK1/2 and CREB (Fig. 3C). Besides the p38-related pathway activation, we also found that SUV or UVB induced phosphorylation of several other kinases and transcription factors including paxillin (Y118), Src (Y419), PLCr-1 (Y783), Fyn (Y402), Yes (Y426), STAT1 (Y701), STAT3 (Y705), STAT4 (Y693) and STAT 5β (Y699) (Supplementary Fig. 3). To further confirm that the p38α signaling pathway dominates the cellular response to SUV in keratinocytes, we conducted the phospho-kinase array assay over a time course, harvesting cells at 15, 60 or 180 min after irradiation. Again we found that, compared to other kinases, p38α signaling was dramatically changed in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. 4). The Western blot data for the same batch of cell lysates was consistent with the results of the array analysis (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3. The p38α signaling pathway is strongly activated by UVB or SUV irradiation.

(A) N/TERT-1 cells were cultured with keratinocyte-sfm medium and starved for 24 h. The cells were irradiated with UVA (60 kJ/m2), UVB (3.6 kJ/m2) or SUV (60 kJ UVA/m2/3.6 kJ UVB/m2). Protein extracts (500 µg) were used for a phospho-kinase array analysis. Array spots were visualized using an ECL kit. (B) The density of the each duplicated array spot in A was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The graph shows the fold change in SUV-induced phosphorylation of JNKs, c-Jun, p38α, MSK1/2, and HSP27 compared to untreated control (i.e., value of 1). Data are shown as an average of duplicate samples. (C) Cell lysates (30 µg) from A were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection kit after hybridization with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody.

Fig. 4. The p38α signaling pathway is strongly activated by SUV in a time-dependent manner.

(A) N/TERT-1 cells were cultured with keratinocyte-sfm medium and starved for 24 h. The cells were irradiated with SUV (60 kJ UVA/m2 /3.6 kJ UVB/m2) and harvested at various times (0, 15, 60, or 180 min). Protein extracts (500 µg) were used for phospho-protein array analysis. Array spots were visualized using an ECL kit (left panel). The density of the each duplicated array spot was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The graph shows the fold change in SUV-induced phosphorylation of JNKs, c-Jun, p38α, MSK1/2, and HSP27 compared to untreated control (i.e., value of 1). Data are shown as an average of duplicate samples (right panel). (B) Cell lysates (30 µg) from A were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. The protein levels of p38, MSKs and CREB were determined using specific antibodies. Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection kit after hybridization with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody.

A dominant negative inactive p38 increases the incidence of SUV-induced skin tumorigenesis in SKH-1 hairless mice

The p38 protein plays a functional role in UVB-induced carcinogenesis (29–30). To further investigate the role of p38 in SUV-induced skin carcinogenesis, we exposed p38 domain negative (DN) and wildtype SKH-1 hairless mice to SUV for 15 weeks and then stopped treatment and observed tumor growth for an additional 15 weeks. The results indicated that tumors began to emerge at week 27 but the p38 DN mice exhibited fewer and smaller tumors compared to wildtype mice (Fig. 5A, B, C). The average number of SUV-induced tumors per mouse was significantly decreased in SKH-1 p38 DN mice compared with wildtype mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 5B). The size (mm3) of tumors in SUV-treated mouse skin was also significantly decreased in SKH-1 p38 DN mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 5C). Skin and tumor samples were processed for H&E staining. After treatment with SUV, epidermal thickness in wildtype mice was increased by edema and epithelial cell proliferation, whereas SKH-1 p38 DN mice showed a much smaller increase in epidermal thickness and inflammation (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5. Inactivation of p38α inhibits SUV-induced skin tumorigenesis in SKH-1 hairless mice.

Mice were divided into 4 groups: Groups 1 & 2: no SUV irradiation SKH-1 Wt and SKH-1-p38 DN (control); Groups 3 & 4: SUV treated SKH-1 Wt and SKH-1-p38 DN. SUV exposure is detailed in Materials and Methods. (A) External appearance of tumors. (B) Average tumor number per mouse. (C) Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: tumor volume (mm3) = (length × width × height × 0.52). Data are shown as means ± S.E. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the SKH-1 Wt and SKH-1-p38 DN groups irradiated with SUV. (D) Skin and tumor samples were fixed in 10% NBF and processed for H&E staining.

Discussion

Solar ultraviolet irradiation (SUV) or sunlight has been recognized as an environmental factor in the development of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers for many years. SUV comprises approximately 95% UVA and 5% UVB. Both UVA and UVB can activate signal transduction pathways related to cell survival (16, 21). However, under normal sunlight conditions, both UVA and UVB irradiate skin. The identification of the cellular signaling pathway(s) evoked by SUV and their role in skin carcinogenesis needs to be further addressed. Here, UV-340 lamps were used to mimic SUV and to irradiate human N/TERT-1 normal keratinocytes. We found that SUV (60 kJ UVA/m2/3.6 kJ UVB/m2), which is equal to 15 min of sun exposure in Austin, Minnesota in midsummer from 2 to 4 pm, can activate p38α and JNKs (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

The MAPKs play a major role in UV-induced skin cancer development (28). A phospho-MAPK array analysis indicated that p38α and its downstream target proteins, MSK2 and HSP27, were strongly activated by UVB and SUV (Fig. 2A, B). However, other isoforms of p38, including p38β, p38γ, and p38δ were not affected (Supplementary Fig 2). Moreover, phospho-kinase array and Western blot data also clearly indicated that the p38α-signaling pathway was strongly activated by UVB and SUV irradiation (Fig. 3A, B, C; Fig. 4A, B). These data provide firm evidence that p38α signaling is the pathway most strongly activated by SUV. Besides p38α signaling, JNK signaling was also activated after SUV irradiation and its role in SUV-induced skin carcinogenesis needs to be elucidated in future studies. Interestingly, the kinase activation pattern was similar in UVB- and SUV-induced signaling, which implies that UVB plays a major role in SUV-induced signaling. Surprisingly, we found that ERKs phosphorylation (T202/Y204) was decreased in UVA, UVB, or SUV treated N/TERT-1 cells. This phenomenon has also been observed in UV-irradiated human lung adenocarcinoma ASTC-a-1 cells. The ERKa inactivation by UV might be related to the activation of the JNKs/Forkhead box O (FOXO) transcription factors (31). JNKs activation of c-Jun can result in the transcription of ERKs phosphatases, which are involved in ERKs inactivation (32). Interestingly, ERKs activation can be observed in JB6 and HaCaT cells (16, 18, 33). The ERKs activation in these cell lines likely involves EGFR activation by UV (33–35). Besides the MAPKs, several other kinases and transcription factors, including Fyn, Src, and PKC (14, 19–20) have been reportedly activated by UVB irradiation. Here, we also found that paxillin (Y118), Src (Y419), PLCr-1(Y783), Fyn (Y402), Yes (Y426), STAT1 (Y701), STAT3 (Y705), STAT4 (Y693) and STAT 5β (Y699) were activated by SUV and UVB irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 3, 4).

The p38 signal transduction pathway has been implicated in both suppression and promotion of tumorigenesis. Inhibition of p38 can reduce acute UVB-induced inflammation and chronic UVB-induced skin cancer (9). The p38-regulated/activated protein kinase (PRAK), a substrate of p38, plays an important role in Ras-induced senescence and tumor suppression (36). However, activation of p38 is also critical for the anti-proliferation effect of β-elemene (37). These reports suggest that the role of p38 in tumorigenesis may be cell-specific and tissue-dependent. Here, p38 dominant negative (DN) SKH-1 mice were used to investigate the role of p38 in SUV-induced skin cancer. The results indicated p38 DN mice developed less skin tumors and exhibited slower tumor growth compared to wildtype mice (Fig. 5), which is consistent with the signaling activation induced by UVB. These data indicated that p38 is dramatically activated by SUV and plays a functional role in SUV-induced skin carcinogenesis. Besides p38, the mechanism probably involves p38 downstream substrates, MSK, CREB and HSP27, which are also important in carcinogenesis (38–39). Furthermore, p38 also regulates AP-1 and its target gene cox-2, which also play a role in TPA-induced inflammation and carcinogenesis (40).

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that the p38α signal transduction pathway is markedly activated by SUV irradiation and p38α plays a vital role in chronic SUV-induced skin cancer. Our work also suggests that p38α might be a promising target for skin cancer chemoprevention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Hormel Foundation and National Institutes of Health grants CA027502, CA077646, CA120388, ES016548, R37 CA081064. We thank Tonya Poorman for assistance in submitting our manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.de Gruijl FR. Skin cancer and solar UV radiation. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:2003–2009. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berwick M, Lachiewicz A, Pestak C, Thomas N. Solar UV exposure and mortality from skin tumors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;624:117–124. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeifer GP, You YH, Besaratinia A. Mutations induced by ultraviolet light. Mutat Res. 2005;571:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mabruk MJ, Toh LK, Murphy M, Leader M, Kay E, Murphy GM. Investigation of the effect of UV irradiation on DNA damage: comparison between skin cancer patients and normal volunteers. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:760–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussein MR. Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer: molecular mechanisms. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:191–205. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reifenberger J, Wolter M, Knobbe CB, Kohler B, Schonicke A, Scharwachter C, et al. Somatic mutations in the PTCH, SMOH, SUFUH and TP53 genes in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Gruijl FR, van Kranen HJ, Mullenders LH. UV-induced DNA damage, repair, mutations and oncogenic pathways in skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;63:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Deiry WS. Targeting mutant p53 shows promise for sunscreens and skin cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3658–3660. doi: 10.1172/JCI34251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson SE, Olson ER, Zhang J, Cooper SJ, Melton T, Criswell PJ, et al. p38 MAP kinase plays a functional role in UVB-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50:469–478. doi: 10.1002/mc.20734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheeler DL, Martin KE, Ness KJ, Li Y, Dreckschmidt NE, Wartman M, et al. Protein kinase C epsilon is an endogenous photosensitizer that enhances ultraviolet radiation-induced cutaneous damage and development of squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7756–7765. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawasumi M, Lemos B, Bradner JE, Thibodeau R, Kim YS, Schmidt M, et al. Protection from UV-induced skin carcinogenesis by genetic inhibition of the ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13716–13721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hafner C, Landthaler M, Vogt T. Activation of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in non-melanoma skin cancer is not mediated by oncogenic PIK3CA and AKT1 hotspot mutations. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:e222–e227. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S, Zhu F, Zykova T, Kim MO, Cho YY, Bode AM, et al. T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK) phosphorylation of MKP1 protein prevents solar ultraviolet light-induced inflammation through inhibition of the p38 protein signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29601–29609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.225813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KM, Lee KW, Jung SK, Lee EJ, Heo YS, Bode AM, et al. Kaempferol inhibits UVB-induced COX-2 expression by suppressing Src kinase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:2042–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He YY, Council SE, Feng L, Chignell CF. UVA-induced cell cycle progression is mediated by a disintegrin and metalloprotease/epidermal growth factor receptor/AKT/Cyclin D1 pathways in keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3752–3758. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zykova TA, Zhu F, Zhang Y, Bode AM, Dong Z. Involvement of ERKs, RSK2 and PKR in UVA-induced signal transduction toward phosphorylation of eIF2alpha (Ser(51)) Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1543–1551. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper SJ, Bowden GT. Ultraviolet B regulation of transcription factor families: roles of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kappaB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) in UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:325–334. doi: 10.2174/156800907780809714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Malakhova M, Mottamal M, Reddy K, Kurinov I, Carper A, et al. Norathyriol suppresses skin cancers induced by solar ultraviolet radiation by targeting ERK kinases. Cancer Res. 2012;72:260–270. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byun S, Lee KW, Jung SK, Lee EJ, Hwang MK, Lim SH, et al. Luteolin inhibits protein kinase C(epsilon) and c-Src activities and UVB-induced skin cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2415–2423. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang NJ, Lee KW, Shin BJ, Jung SK, Hwang MK, Bode AM, et al. Caffeic acid, a phenolic phytochemical in coffee, directly inhibits Fyn kinase activity and UVB-induced COX-2 expression. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:321–330. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syed DN, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Differential activation of signaling pathways by UVA and UVB radiation in normal human epidermal keratinocytes(dagger) Photochem Photobiol. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2012.01115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano H, Gasparro FP, Uitto J. UVA-340 as energy source, mimicking natural sunlight, activates the transcription factor AP-1 in cultured fibroblasts: evidence for involvement of protein kinase-C. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74:274–282. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0274:uaesmn>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zykova TA, Zhang Y, Zhu F, Bode AM, Dong Z. The signal transduction networks required for phosphorylation of STAT1 at Ser727 in mouse epidermal JB6 cells in the UVB response and inhibitory mechanisms of tea polyphenols. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:331–342. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickson MA, Hahn WC, Ino Y, Ronfard V, Wu JY, Weinberg RA, et al. Human keratinocytes that express hTERT and also bypass a p16(INK4a)-enforced mechanism that limits life span become immortal yet retain normal growth and differentiation characteristics. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1436–1447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1436-1447.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donovan N, Becker EB, Konishi Y, Bonni A. JNK phosphorylation and activation of BAD couples the stress-activated signaling pathway to the cell death machinery. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40944–40949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao K, Cho YY, Bode AM, Vummenthala A, Park JG, Liu K, et al. A selective small-molecule inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2208–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi HS, Bode AM, Shim JH, Lee SY, Dong Z. c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 phosphorylates Myt1 to prevent UVA-induced skin cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2168–2180. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01508-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bode AM, Dong Z. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in UV-induced signal transduction. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:RE2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.167.re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen W, Tang Q, Gonzales MS, Bowden GT. Role of p38 MAP kinases and ERK in mediating ultraviolet-B induced cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in human keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2001;20:3921–3926. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jinlian L, Yingbin Z, Chunbo W. p38 MAPK in regulating cellular responses to ultraviolet radiation. J Biomed Sci. 2007;14:303–312. doi: 10.1007/s11373-007-9148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Chen WR, Xing D. A pathway from JNK through decreased ERK and Akt activities for FOXO3a nuclear translocation in response to UV irradiation. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1168–1178. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sprowles A, Robinson D, Wu YM, Kung HJ, Wisdom R. c-Jun controls the efficiency of MAP kinase signaling by transcriptional repression of MAP kinase phosphatases. Exp Cell Res. 2005;308:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashida M, Bito T, Budiyanto A, Ichihashi M, Ueda M. Involvement of EGF receptor activation in the induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in HaCaT keratinocytes after UVB. Exp Dermatol. 2003;12:445–452. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2003.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Dong Z, Bode AM, Ma WY, Chen N. Induction of EGFR-dependent and EGFR-independent signaling pathways by ultraviolet A irradiation. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:769–779. doi: 10.1089/104454901753438589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan YS, Wang ZQ, Shao Y, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Ultraviolet irradiation activates PI 3-kinase/AKT survival pathway via EGF receptors in human skin in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:461–466. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun P, Yoshizuka N, New L, Moser BA, Li Y, Liao R, et al. PRAK is essential for ras-induced senescence and tumor suppression. Cell. 2007;128:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao YQ, Ding X, Jia YC, Huang CX, Wang YZ, Xu YH. Anti-tumor effect of beta-elemene in glioblastoma cells depends on p38 MAPK activation. Cancer Lett. 2008;264:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jean D, Bar-Eli M. Regulation of tumor growth and metastasis of human melanoma by the CREB transcription factor family. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;212:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamada M, So A, Muramaki M, Rocchi P, Beraldi E, Gleave M. Hsp27 knockdown using nucleotide-based therapies inhibit tumor growth and enhance chemotherapy in human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:299–308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chun KS, Kim SH, Song YS, Surh YJ. Celecoxib inhibits phorbol ester-induced expression of COX-2 and activation of AP-1 and p38 MAP kinase in mouse skin. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:713–722. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.