Abstract

Familial multiple exostosis in a family of seven members who are affected found that exostosis was arising both from bones of enchondral as well as membranous ossification, which was sessile as well as pedunculated and was larger in size at the growing ends of the bones. The lesions occur only in bones that develop from cartilage (endochondral ossification). In our study, we have noticed lesions occurring in both endochondral as well as membranous bone. Till now, no article has mentioned about membranous origin (clavicle).

Keywords: Autosomal dominant, diaphyseal aclasis, general anaesthesia, hereditary multiple exostosis, histopathology

INTRODUCTION

It is rare AD genetic disorder characterized by multiple exostosis, prevalence 1 in 30,000, M:F radio is 1:5:1 with incomplete penetrance in female. The presence of a painless mass around joints that slowly increases with age until puberty is suggestive of the diagnosis.[1]

CASE REPORT

A 10-year-old boy presented with generalised hard lumps all over the body with family members similarly affected – his father, grandfather, father's elder sister, younger brother, and cousin sister (daughter to his father's elder sister).

The patient presented with generalised hard lumps all over the body that were hard, non-tender and started as smaller size, which gradually increase in size to the present size in a few months. These lumps first appeared around the right wrist at the age of 2 years, and by the age of 5 years became generalized, appearing around both knee regions and upper back and left wrist, both shoulders, hips and both ankles. Around 7 years of age, the lumps also appeared on the chest and both clavicles.

He had restriction of movement, especially at both knees, and had difficulty in squatting and lying down on the sides. From the last 2 years, the lumps had been growing rapidly.

Examination of the patient revealed a short stature with multiple hard lumps of size 0.5–10 cm, non-tender and non-mobile over both ends of the clavicle, medial border of scapulae, proximal humerai, both distal radius and ulna and bilateral metacarpals and phalanges, both iliac crest, proximal fumerae, supracondylar region of both femur and proximal and distal metaphyseal regions of both tibia and fibula. All long bones had deformed restriction of movement at the bilateral elbow, wrist and pronation and supination with fixed flexion deformity of 20° of both knee restriction of knee flexion about 30° short of full flexion, with small bony hard lumps also present on several ribs anteriorly and no neurovascular deficit [Figures 1–11]. Knobby appearance due to exostosis on many of the bones was noted. This appearance is so striking that the condition can be diagnosed by mere inspection of the subject[2] [Figures 7 and 8].

Figure 1.

Exostoses of sternal end of clavicle

Figure 11.

Exostoses of iliac bone back side

Figure 7.

Knobby apearance of all the limbs

Figure 8.

Exostoses of both scapula

Figure 2.

Exostoses of sternal end of clavicle

Figure 3.

Exostoses arising from rib

Figure 4.

Exoses of distal third of forearm

Figure 5.

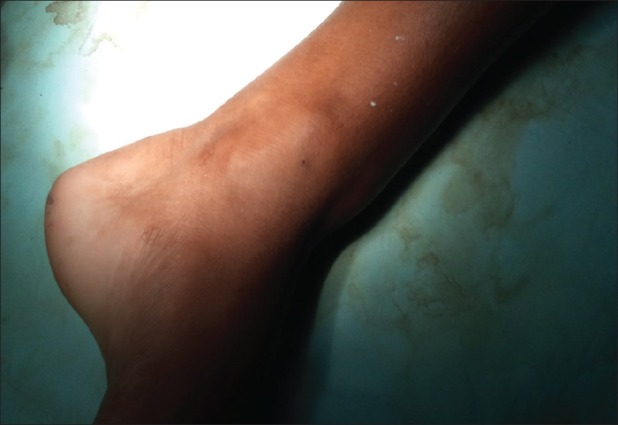

Exostoses of distal third of leg

Figure 6.

Exostoses of proximal third of leg

Figure 10.

Exostoses of right forearm and iliac bone

The stature is short or even dwarfed. The limb is short in relation to the trunk, with superficial resemblance to achondroplasia[3] [Figures 9 and 11].

Figure 9.

Exostoses of scapula and both iliac bones

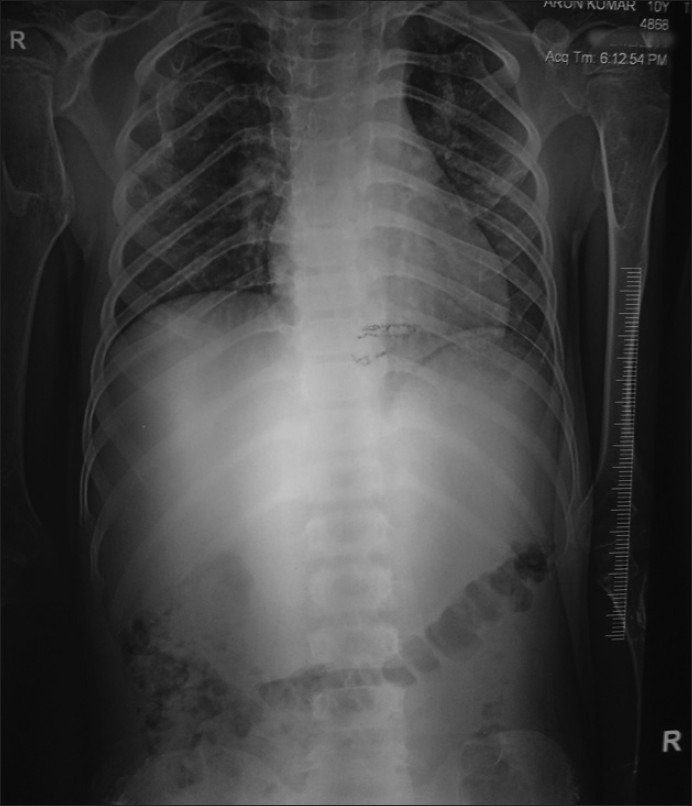

X-ray shows multiple bony mass present on the bilateral clavicle at the sternal end, right-sided 3rd and 4th rib at the anterior axillary line, right-sided proximal humerus and bilateral distal end of radius and ulna, at the distal end of the right 2nd metacarpal head, bilateral right distal femur, proximal tibia, proximal fibula, distal end tibia and fibula [Figures 12–16].

Figure 12.

Family members involved out of seven

Figure 16.

X-ray showing exostoses at both sternal end of clavicles

X-ray shows sessile bony masses projecting from both iliac bones and proximal femorae [Figure 12].

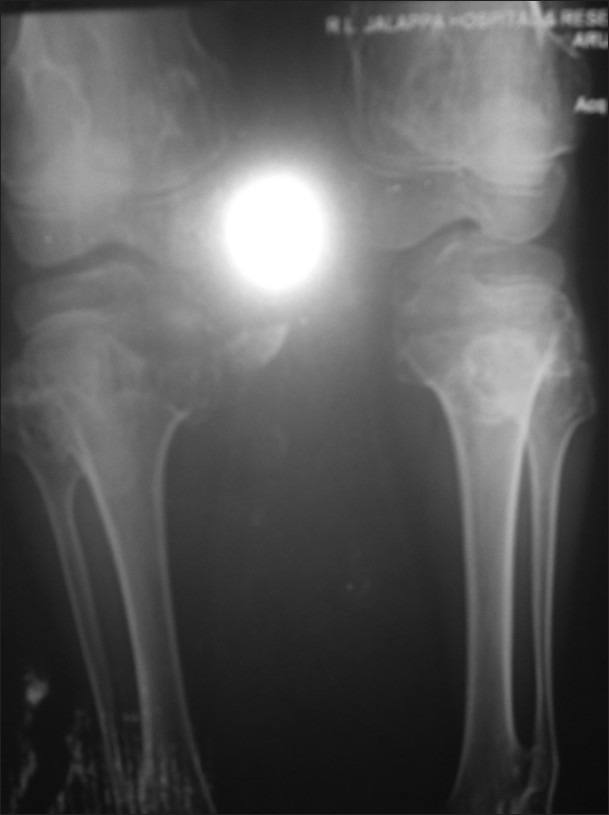

X-ray shows left-sided pedunculated mass and sessile mass at the right side of the metaphysic of distal femur metaphyses that are broadened and trumpet shaped [Figures 13 and 14].

Figure 13.

X-ray pelvis showing exostoses of both proximal femur and ilium

Figure 14.

X-ray showing both proximal and distal femoral involvement

Figure 15 shows a sessile mass at both sternal ends of the clavicles.

Figure 15.

X-ray showing exostoses of proximal and distal tiba and fibula with distal femur

Figure 16 shows sessile masses on both the first metatarsal heads.

Figure 17 shows an—X-ray of ulnar shortening with medial bowing and distal radial broadening with exostosis from the medial part of the metaphyseal region of the radial and lateral parts of the metaphyseal region of the ulna.

Figure 17.

X-ray showing exostoses of metaphysealatrsal head of both lower limbs

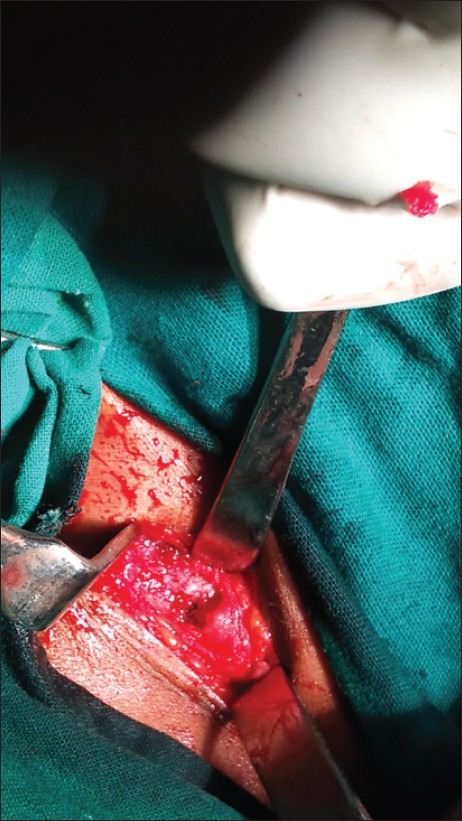

Masses were excised under general anesthesia in two sittings [Figures 18 and 19] bony masses excised from bilateral clavicle at sternal end, right-sided 3rd and 4th rib at the anterior axillary line, right-sided proximal humerus and bilateral distal end of radius and ulna, at the distal end of the right 2nd metacarpal head, bilateral right distal femur and proximal tibia and proximal fibula (common peroneal was secured) and distal end tibia and fibula [Figures 17, 20–23]. The patient was sent for histopathology and was confirmed to be exostosis [Figure 24].

Figure 18.

Masses excised at first surgery

Figure 19.

Masses excised at second surgery

Figure 20.

X-ray showing exostoses of distal end of radius, ulna and 2nd metacarpal head

Figure 23.

Exostoses of the distal ulna

Figure 24.

Exostoses of second metacarpal

Figure 21.

Exostoses of clavicle at sternal end

Figure 22.

Exostoses of clavicle at sternal end after excision of mass

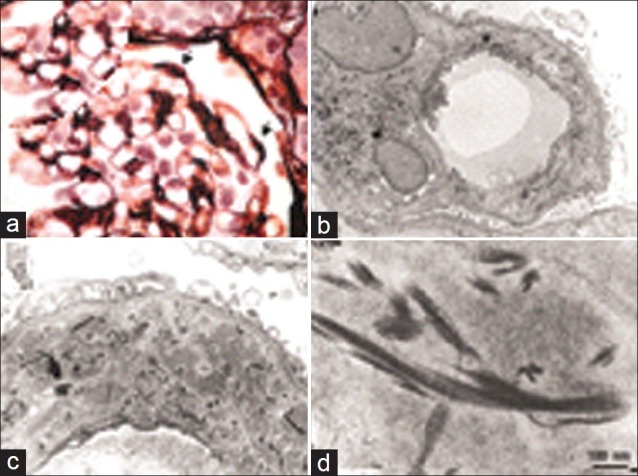

Histopathology report

At microscopic examination, the cartilage cap appears to merge with the underlying bone and is covered with a thin layer of fibrous capsule. The cartilage cap resembles a growth plate with columns or clusters of chondrocytes that are evenly distributed and maturing [Figure 25].

Figure 25.

Histopathology report

DISCUSSION

History tends to confirm the importance of congenital developmental defects as a cause and their transmission from father to offspring.[4] In this case, the multiple exostoses is hereditary, being transmitted through three generations, with the affected members being short statured with deformed bone due to defective remodelling.

Greater deposition of fat at puberty in female subjects may prevent small exostosis from being detected. It is possible that some of the female carriers in whom the gene was not apparently expressed were in fact mildly affected, but the lesions were confined to the regions of the skeleton that were difficult to palpate.[5]

The arthrometric data indicates that person with hereditary exostosis are of short statured, but actual dwarfism is rare.[6]

Majority of the growth from bone is cancellous in nature, and bones affected the most are ulna, fibula, femur, tibia, humerus and phalanges.[3] The term diaphyseal aclasis (commonly used in British literature) indicates that the modeling of the entire affected bone area is abnormal.[7]

The disorder is of autosomal-dominant inheritance, with penetrance approaching 96%. If a person whose family is affected by hereditary multiple exostosis has not had an exostosis by 12 years of age, it is unlikely that exostosis will develop later.[2]

In our case, exostosis was arising from membranous bone (bilateral clavicle) as well as endochondral ossified bones.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kulkarni GS. Benign skeletal tumours. 2nd ed. Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2008. Textbook of orthopaedics and trauma; pp. 1024–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Companacci M. Bone and soft tissue tumours. New York: Springer-Verlag Wein; 1990. pp. 355–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis GG. Multiple cartilaginous exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1906;S2-3:234–49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall HW. A case of multiple cartilaginous exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg. 1916;S2-144:346–59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmale GA, Conrad EU, 3rd, Raskind WH. The natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:986–92. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro F, Simon S, Glimcher MJ. Hereditary multiple exostoses. Anthropometric, roentgenographic and clinical aspects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:815–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schajowicz F, Sissons HA, Leslie HS. THE world Health Organization's histologic classification of bone tumours. A commentary on the second edition. Cancer. 1995;75:1208–14. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950301)75:5<1208::aid-cncr2820750522>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]