Abstract

Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus are known to cause skin and soft tissue infection. They can also cause necrotising pneumonia in otherwise healthy individuals. Here we report a case of severe, necrotising, haemorrhagic pneumonia in a 12-year-old boy who presented with a four-day history of a sore throat and fever. During his admission he deteriorated and needed full ventilatory support but despite all efforts he died. Postmortem examination lung swabs confirmed the presence of PVL-associated S aureus. There is a need to improve awareness of this disease among medical practitioners as early diagnosis and appropriate management can save lives.

Background

Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for 2% of community-acquired pneumonias and 10% of nosocomial chest infections.1 Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) was first described in 1932 and was named after the authors of that paper.2

PVL is a toxin produced by some strains of Staphylococcus aureus which destroys white blood cells (WBCs). Different mechanisms have been hypothesised to describe the pathogenecity of PVL.3 The PVL toxin is encoded by two genes lukS-PV and lukF-PV and detection of these genes is the main way to identify PVL.4

PVL is detected in less than 2% of S aureus isolates.3 The death rate of PVL-positive S aureus pneumonia has been reported to approach 75%.2 Worldwide it is more prevalent in closed communities and among close contacts.3 The first reported case of severe community-acquired pneumonia caused by PVL-positive S aureus in the UK was in 2003.5

Case presentation

A previously healthy 12-year-old boy presented to the accident and emergency department of a district general hospital with a history of a sore throat for 4 days. He had developed a cough and had been seen by his general practitioner (GP) the day before admission. There were no signs of pneumonia or other serious illness at that time and advice regarding symptomatic treatment was given. The following day he remained much the same and his appetite improved that evening. However, within a couple of hours he experienced increasing respiratory distress and worsening cough which was now productive of a small amount of blood. His parents took him to the GP Out of Hours Service and he was transferred to the accident and emergency department.

On admission he looked pale, clammy and tachypnoeic but was able to speak in sentences. His oxygen saturation was recorded as 92% on 40% oxygen with a respiratory rate of 44, pulse rate of 140 and blood pressure of 110/72. Chest auscultation revealed decreased air entry bilaterally and scattered rhonchi and coarse crepitations at both lung bases. He was given salbutamol and ipatropium bromide via a nebuliser. His initial arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.3, pCO2 of 4.9 and pO2 of 9.6. A provisional diagnosis of pneumonia was made and he was started on intravenous cefuroxime. Initial blood tests indicated mild renal dysfunction with a raised urea (9.7 mmol/l) and creatine (160 µmol/l). The WBC count (0.9×109/l) and neutrophil count (0.41×109/l) were both very low and the C reactive protein (CRP) was very high at greater than 250.

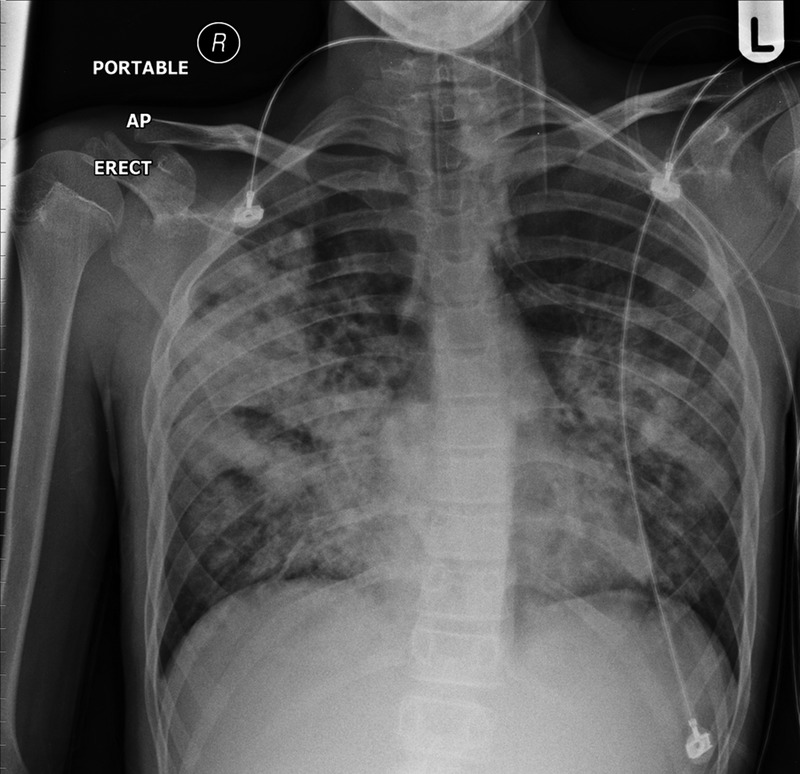

He continued to have haemoptysis and it was thought that he might have Goodpasture syndrome. It was evident that he was becoming more distressed and uncomfortable and he was complaining of back pain. There were no indications of a bleeding disorder or an intra-abdominal problem. The first chest x-ray (figure 1) showed extensive bilateral infiltrates particularly in both mid-zones. At this stage the paediatric intensive care unit in the tertiary hospital was contacted and it was decided that he should be transferred to the tertiary hospital's high dependency unit as it was likely that he would need ventilatory support and possibly renal support over the next few hours.

Figure 1.

x-Ray taken on admission showed bilateral pulmonary shadowing.

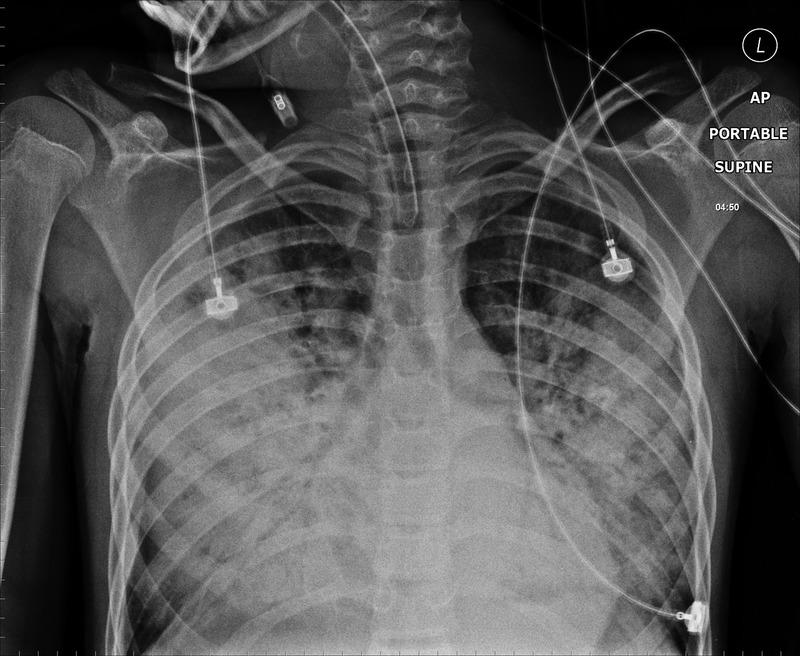

By the time transfer arrangements were made he had deteriorated significantly. His heart rate increased, perfusion was poor, haemoptysis had worsened and he required more oxygen. The arterial blood gas showed deterioration with a pH of 7.23 and pCo2 of 6.9. The anaesthetist was called to help intubate, ventilate and stabilise the patient. Direct layrngoscopy revealed a lot of blood welling up from the lungs and this continued after he was intubated. Immediately after intubation he had a pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest and was given cardiopulmonary resuscitation. He received four doses of epinephrine after which he resumed sinus rhythm but remained significantly bradycardic. The chest x-ray was repeated (figure 2), and showed extensive bilateral alveolar pulmonary shadowing. Over the next few hours it proved extremely difficult to ventilate him adequately and for most of the time his pH was <7.0. Various different ventilation strategies were tried with little success in reducing the level of hypercapnia and blood continued to come up the endotracheal tube in significant volumes. He required repeated doses of epinephrine and an epinephrine infusion for hypotension and bradycardia.

Figure 2.

Six hour after the first x-ray. There is an extensive bilateral alveolar pulmonary shadowing. ET tube position is satisfactory.

Outcome and follow-up

Despite all these efforts he underwent a second cardiac arrest. Resuscitation was carried out but he could not be revived.

The postmortem report indicated that he had died of bilateral necrotic pneumonia. Swab cultures of both lungs and pleural surfaces grew Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive (toxin producing) S aureus. It was described that numerous and large areas of lung parenchyma showed ‘massive’ necrotising and gangrenous inflammation along with number of bacterial colonies, multiple abscess formation and expansion of this inflammation to the pleural surface and space. Patches of haemorrhage and oedema were also identified. The kidneys showed ‘non-specific changes secondary to multiorgan failure’ which developed as a result of overwhelming staphylococcus infection. The brain was ‘markedly oedematous and the prominent vessels of the meninges showed no inflammation, haemorrhage or other changes’.

Discussion

PVL producing S aureus can be methiciline resistant (MRSA) or sensitive (MSSA). The majority (62%) of referred isolates in the reference laboratory were MSSA in 2006.3

Community onset, PVL-positive disease commonly causes skin and soft tissue infections such as boils, carbuncles and cellulitis and is usually treated on an outpatient basis.6 7 Musculoskeletal infections were found to be the most common type of PVL-positive infections and these commonly spread to other sites and led to sepsis and multiorgan failure.4 Cunnington et al4 identified 11 cases of PVL-positive MSSA causing invasive disease. The other forms of invasive diseases caused by PVL-positive S aureus are necrotising fasciitis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, pyomyositis and purpura fulminans.3 8 Relatively few patients diagnosed with necrotising pneumonia have a previous history of skin infection.2

PVL producing S aureus can cause rapidly progressive, haemorrhagic and necrotising pneumonia in mainly otherwise healthy patients, young patients and men.6 8 9 It can also lead to pulmonary abscess formation, cavitation or pleural effusion.2

Thomas et al10 reported a case series where community-acquired MSSA producing PVL toxin caused pneumonia with complications including bilateral multilobular infiltrates, pneumatocoeles, recurrent pneumothoraces, pleural effusion, empyema, lung abscess and diaphragmatic paralysis. Mushtaq et al reported a 14-year-old child who presented initially with sore throat and fever and then deteriorated rapidly. He developed hypotension, multiple organ failure and purpura fulminans. S aureus positive for PVL, toxic shock syndrome toxins 1 and 2 and staphylococcal enterotoxin C were isolated from tracheal aspirate. These toxins were responsible for purpura fulminans and toxic shock syndrome11 Trieu et al reported another case of young girl who initially developed flu-like symptoms with a low-grade temperature. The parents were not worried and she went to bed. The next morning she was found dead in her bed. Postmortem examination revealed necrotising pneumonia caused by PVL-positive S aureus.12 PVL-positive MRSA can cause primary community-acquired pneumonia as well as metastatic pulmonary disease.13 In hospital, community acquired pneumonia is diagnosed when it is during the first 48 h of admission.2

Gillet et al compared PVL-positive and PVL-negative S aureus pneumonias. The survival rate at 48 h was only 63% in PVL-positive patients while for PVL-negative patients it was 94%.

Lina et al14 detected PVL genes in 93% of the S aureus strains isolated from furunculosis and 85% of those which are associated with severe necrotic haemorrhagic pneumonia.

PVL-SA pneumonia is usually preceded by ‘flu-like’ illness with or without diarrhoea and vomiting. Flu-like symptoms are present in 75% of the cases.9 The classic features are fever >39°C, tachycardia >140 bpm, haemoptysis, hypotension, marked leukopenia and high CRP (usually >200). Chest radiograph shows multilobar infilterates which are usually <3 cm diameter.2 Survival rate is <10% when WBC count is <1×109/l and exceeds 85% if WBC count is >10×109/l.9

The health protection agency (HPA) has published a guideline on the diagnosis and management of PVL-associated S aureus in England.3 The initial management of suspected PVL-SA pneumonia should include aggressive ventilatory support as pulmonary haemorrhage and lung tissue destruction causes significant, ongoing hypoxia. Prone ventilation, the use of nitric oxide and extra-corporeal membrane oxygen may be required.15 Combinations of vancomycin, clindamycin, linezolid and rifampicin have been used and no one antibiotic has proven superior to another. Co-trimoxazole is not recommended.3 Conventional doses of Vancomycin have no effect on exotoxin formation and have inadequate lung penetration so it is not recommended for sole use.2

Intravenous immunoglobulin is also recommended with the dose of 2 g/kg. It can be repeated after 48 h if there is still evidence of sepsis.3 It neutralises the PVL pore forming and cytopathic effect in vitro.2

The HPA guideline recommends barrier nursing and the use of face masks especially when performing airway manoeuvres, physiotherapy and suction.3

The health protection unit in London and south east England, carried out an audit in 2008–2009 and followed up the PVL-SA cases and contacts. They concluded that contact tracing can be resource intensive as only 1.4/1000 cases of serious illness annually can be prevented.16

There is a need to create more awareness of this condition among medical and nursing staff. Freeman et al conducted a telephone survey in England asking paediatric registrars questions regarding PVL. Only 7% of registrars knew the full name and just 17% could correlate this with staphylococci.17

In summary, our patient was a healthy individual who presented to hospital with history of sore throat for 4 days. Within a few hours of his arrival at hospital his condition deteriorated. In spite of having appropriate medical treatment he did not survive.

This case highlights the importance of PVL producing S aureus causing fatal necrotising pneumonia. Early diagnosis and treatment with appropriate antibiotics and early ventilatory support is required to treat this infection.

Learning points.

Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) producing staphylococcal infection can cause severe necrotising pneumonia in otherwise healthy young adults. The associated mortality rate is very high.

If a child presents with haemoptysis, tachypnoea, tachycardia and leucopoenia PVL producing Staphylococcus aureus necrotising pneumonia should be considered.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gillet Y, Issartel B, Vanhems P, et al. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet 2002;359:753–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan MS. Diagnosis and treatment of Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) associated staphylococcal pneumonia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007;30:289–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HPA Guidance on the diagnosis and management of PVL-associated Staphylococcus aureus infections (PVL-SA) in England. 2008. http://www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1218699411960 (accessed Oct 2011).

- 4.Cunnington A, Brick T, Cooper M, et al. Severe invasive Panton-Valentine leucocidin positive Staphylococcus aureus infections in children in London, UK. J Infect 2009;59:28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein JI, Petrovic Z, Treacher D, et al. Severe community-acquired pneumonia caused by Panton-Valentine leukocidin positive Staphylococcus aureus: first reported case in the United Kingdom. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shallcross LJ, Williams K, Hopkins S, et al. Panton-Valentine leukocidin associated staphylococcal disease: a cross-sectional study at a London hospital, England. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010;16:1644–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes A, Ganner M, McGuane S, et al. Staphylococcus aureus isolates carrying Panton-Valentine leucocidin genes in England and Wales: frequency, characterization, and association with clinical disease. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:2384–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labandeira-Rey M, Couzon F, Boisset S, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin causes necrotizing pneumonia. Science 2007;315:1130–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillet Y, Vanhems P, Lina G, et al. Factors predicting mortality in necrotizing community-acquired pneumonia caused by Staphylococcus aureus containing Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:315–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas B, Pugalenthi A, Chilvers M. Pleuropulmonary complications of PVL-positive Staphylococcus aureus infection in children. Acta Pædiatr 2009;98:1372–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mushtaq F, Hildrew S, Okugbeni G, et al. Necrotizing haemorrhagic pneumonia proves fatal in an immunocompetent child due to Panton–Valentine leucocidin, toxic shock syndrome toxins 1 and 2 and enterotoxin C-producing Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Pædiatr 2008;97:983–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trieu T, Gaudelus J, Lefevre s, et al. Sudden death caused by Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton–Valentine leukocidin gene in a young girl. BMJ Case Rep 2009. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2009.1542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez BE, Hulten KG, Dishop MK, et al. Pulmonary manifestations in children with invasive community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:583–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F, et al. Involvement of Panton-Valentine Leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dise 1999;29:1128–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGrath B, Rutledge F, Broadfield E. Necrotising pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus and Panton-Valentine leukocidin. JICS 2008;9:170–2 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millership S, Cummins A, Irwina D. Follow up of cases of PVL-positive Staphylococcus aureus is not worthwhile. J Infect 2011;62:234–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman HR, Hutchings FA, Marriage SC, et al. Knowledge of Panton–Valentine leukocidin-associated Staphylococcus aureus infections among paediatric registrars in England. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:855–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]