Summary

Macrophages contribute to host defense and to the maintenance of immune homeostasis. On the other hand, they are important targets of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a herpesvirus that has evolved many strategies to modulate the host immune response. Since an efficient macrophage trafficking is required for triggering an adequate immune response, we investigated the effects exerted by HCMV infection on macrophage migratory properties. By using endotheliotropic strains of HCMV, we obtained high rates of productively infected human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM). Twenty-four hours after infection, MDM showed reduced polar morphology and became unable to migrate in response to inflammatory and lymphoid chemokines, bacterial products and growth factors, despite being viable and metabolically active. While chemotactic receptors were partially downregulated on the surface of infected MDM, HCMV induced a dramatic reorganization of the cytoskeleton characterized by rupture of the microtubular network, stiffness of the actin fibers and collapse of the podosomes. Furthermore, supernatants harvested from infected MDM contained high amounts of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and were capable to block the migration of uninfected macrophages. Since the immunodepletion of MIF completely restored MDM chemotaxis, we could prove that MIF was indeed responsible for the reduced cell migration. In conclusion, these findings reveal that HCMV employs different mechanisms in order to interfere with movement and positioning of macrophages, possibly leading to an impairment of antiviral responses and to an enhancement of the local inflammation.

Keywords: monocytes/macrophages, viral infection, chemokines, chemotaxis, inflammation

Introduction

Macrophages with their numerous biologic functions have long been recognized as key cells in the mammalian host defense. Due to their capacity to phagocyte foreign materials and dying cells, to digest bacteria and viruses, to present antigens and to secrete regulatory and inflammatory mediators, these cells are essential for the reactivity of the immune system (1). On the other hand, macrophages have been implicated in the onset and progression of various chronic diseases, such as certain forms of cancers, vascular diseases and autoimmune diseases (2). Interestingly, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a widespread herpesvirus that has evolved multiple immune evasion strategies to persist and replicate even in a fully immunocompetent host (3), targets both macrophages and their precursors, e.g. monocytes. Though it is still not known whether HCMV plays a causative role or instead it is simply an epiphenomenon, laboratory signs of an active HCMV infection have been observed in certain solid tumors (colon cancer, prostate cancer and malignant glioblastoma (4)), atherosclerosis (5) and autoimmune diseases, such as bowel inflammatory diseases (6), rheumatoid arthritis (7), and systemic lupus erythematosus (8). Intriguingly, all these diseases are associated with an accumulation of infiltrating activated macrophages, which represent at the same time a major regulator of local inflammation and a target of HCMV infection. Circulating monocytes and tissue macrophages are believed to be the predominant cell types harboring HCMV in the peripheral blood (9) and in the infected organs (10), respectively. Therefore, these cells contribute significantly to HCMV pathogenesis serving as vehicles for viral dissemination and as reservoirs for persistent viral infection.

Trafficking properties are crucial for antigen presenting cells in order to execute their immunological functions. Taking into account that HCMV interferes with the motility of other antigen presenting cells, such as dendritic cells and monocytes (11–13), we decided to investigate whether HCMV infection could disturb macrophage motility. It is known that the ordered movements of macrophages are directed by gradients of chemotactic factors that bind to receptors whose expression on the cell surface is highly regulated in order to assure a precise tuning of the cellular flux (14). As a result of activation of chemoattractant receptors, macrophages are stimulated to rearrange their cytoskeleton and consequently to migrate (15).

In this paper, we demonstrate that HCMV is capable to dramatically alter the migratory properties of monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) by interfering with the surface expression of chemokine receptors, the organization of the cytoskeleton and the secretion of soluble inhibitors. It is likely that the resulting macrophage unresponsiveness to chemotactic gradients plays a role in the reported accumulation of macrophage-like cells in those organs and sites and organs where HCMV actively replicates (10). While the relevance of an impairment of macrophage motility is underlined by the existence of diseases, such as X-linked thrombocytopenia and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, characterized by multiple and persistent infections, hemorrhage and autoimmune manifestations (16), the biologic consequences of such inhibition in relation to HCMV pathology in chronic inflammatory diseases still remains to be defined.

Materials and Methods

Establishment of monocyte-derived macrophage (MDM) cultures

PBMC were isolated from buffy coats of HCMV-seronegative blood donors (Institut für Klinische Transfusionsmedizin und Immungenetik Ulm GmbH, Ulm, Germany) by centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque. Monocytes were isolated by negative selection with magnetic microbeads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Monocyte Isolation Kit II, Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and their purity was higher than 95% as assessed by CD14 detection by flow cytometry. 3 × 106 monocytes/ml were then cultured for 7 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, antibiotics, and 100 ng/ml macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN, USA) on hydrophobic lumox dishes (Greiner bio-one GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany) as described (17). The differentiation of MDM occurred over a period of 7 days and was evaluated by morphological criteria, phagocytosis, and flow cytometric analysis (see Table I).

TABLE I.

Phenotypical characterization of monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) generated from human monocytes after 7 days of stimulation with M-CSF

| Antigen | Percentage of positive cells | Mean Fluorescence Intensity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| monocytes | MDM | monocytes | MDM | |

| CD14 | 93 ± 6 | 96 ± 2 | 107 ± 13 | 107 ± 11 |

| CD68 | 10 ± 6 | 95 ± 3 | 9 ± 4 | 69 ± 22 |

| CD64 | 91 ± 3 | 92 ± 3 | 78 ± 13 | 30 ± 12 |

| MHC-I | 99 ± 1 | 99 ± 2 | 130 ± 9 | 100 ± 12 |

| MHC-II | 94 ± 1 | 94 ± 3 | 24 ± 5 | 32 ± 12 |

| CD80 | 95 ± 1 | 87 ± 7 | 11 ± 1 | 38 ± 5 |

| CD86 | 18 ± 9 | 55 ± 16 | 3 ± 1 | 19 ± 5 |

| CD71 | 2 ± 1 | 41 ± 17 | 2 ± 1 | 12 ± 5 |

Assessment of cell number, apoptosis, necrosis and metabolic activity

Flow cytometric evaluation of Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining was used to determine the percentage of viable (Annexin−/PI−), apoptotic (Annexin+/PI−) and necrotic (PI+) cells. At the indicated time points, 1 × 105 MDM were resuspended in 100 μl of Annexin V binding buffer (10mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) and stained with 5 μl Annexin V-FITC (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and 5 μg/ml PI (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany). Cellular metabolic activity was quantified by the MTS tetrazolium metabolization assay (18) using the CellTiter 96® Aqueous One Solution (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Preparation of viral stocks and infection of MDM cultures

Different strains of HCMV were used for the infection of macrophages: the fibroblast adapted strain AD169 and the endotheliotropic strains TB40E and VHLE (kindly provided by Dr. C. Sinzger, University of Tübingen, Germany, and Dr. J Waldman, Ohio State University, USA, respectively). Mycoplasma-negative cell-free viral stocks were prepared from supernatants of infected fibroblasts, frozen at −80°C, titrated and thawed before single use as previously described (13). UV-inactivated virus was prepared as described (13) and was used in the same manner as viable virus. For infection of macrophage cultures, MDM were counted, resuspended in fresh RPMI supplemented with all but M-CSF and inoculated with viral stocks by using a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 plaque-forming unit (PFU) per cell. After 12–16 h, cells were washed with citrate buffer (40 nM Na citrate, 10 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, pH 3.0) to inactivate unabsorbed virus (19). For single-step viral growth curves, MDM were infected as described above and, at the indicated time points after infection, cellular fractions and supernatants were collected separately and stored at −80 °C for successive determination of the infectious titer (20).

Immunofluorescence

MDM were seeded in 8-well Lab-Tek® Chamber Slides (Nalge Nunc International Corp, Naperville, IL, USA) prior mock- or HCMV-infection. For detection of viral proteins, mAbs reactive against the immediate-early proteins 1 and 2 (IE 1-2, pUL122 and pUL123; mAb E13; Argene-Biosoft, Varilhes, France), the early protein p52 (pUL44; mAb CCH2; DAKOCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) and the late tegument protein pp150 (ppUL32; MAb XP1; Dade Behring, Schwalbach, Germany) were used. MDM were fixed with ice-cold methanol/acetone and probed with mAbs against viral antigens, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig (ICN Biomedical, Eschwege, Germany). For visualization of the cytoskeleton, MDM were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated with 0.1 μg/ml FITC-labeled phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich) or with mAbs anti-α-tubulin (Molecular Probes Inc, Eugene, OR, USA) and anti-vimentin (Oncogene Research Product, Boston, MA, USA) followed by TRITC-conjugated anti-mouse Ig (DAKOCytomation). Intracellular macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF) was visualized using rabbit anti-human MIF serum as described in (21). Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Staining was detected using a Zeiss Axioskop2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Flow cytometry

Samples were acquired using a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). For immunophenotyping, MDM were incubated in blocking buffer (10% human immunoglobulins [Flebogamma, Grifols Deutschland GmbH, Langen, Germany], 3% FCS, and 0.01% sodium azide in PBS) containing anti- CD14, CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, HLA-A, B, C (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) or CD68 (DakoCytomation). All mAbs as well as the matching isotypic controls (Immunotech, Hamburg, Germany) were FITC- or PE-conjugated. The expression of chemokine receptors was evaluated using anti- CCR1, CCR2, CCR5, CXCR1, CXCR2, and CXCR4 (R&D System), CCR7 (BD Pharmingen), CX3CR (MBL, Naka-ku Nagoya, Japan) or matching isotypic controls (IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b, DakoCytomation), followed by incubation with PE-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse Ig (DAKOCytomation). MDM were permeabilized by using Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were analyzed using CELLQuest software (BD Immunocytometry Systems), and for each antigen the expression level was measured as percentage of positive cells as well as mean channel fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the respective Ab compared to the isotype-matched control.

Cell migration

Chemotaxis was evaluated using 48-well Boyden chambers (Neuroprobe, Pleasanton, CA, USA) with 5 μm pore polycarbonate filters as previously described (22). Human recombinant MCP-1/CCL2, Rantes/CCL5, Gro-alpha/CXCL1, IL-8/CXCL8, VEGF, M-CSF (R&D Systems), MIP-3beta/CCL19, SDF-1/CXCL12 and Fractalkine/CX3CL1 (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) were used at the final concentration of 100 ng/ml in migration medium (RPMI 1640 1% FCS). fMLP (Sigma Aldrich) was used at the final concentration of 10−8 M. MDM were resuspended in migration medium and seeded 7.5 × 104 cells/well. For each well, the “number of migrated cells” was calculated as number of cells counted in 5 consecutive high power fields (HPF). All stimuli were assayed in triplicates, and results were expressed as mean ± SD.

Actin polymerization assay

Uninfected and HCMV-infected MDM were resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% FCS at a concentration of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml. Following a pre-incubation of 30 min at 37°C, cells were stimulated with either 200 ng/ml Rantes/CCL5 or 500 ng/ml VEGF or 10−7M fMLP for 0, 15, 30, 60, 300 or 900 seconds. Reactions were stopped by fixing the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde. Following permeabilization with 0.1% ice-cold Triton X-100, cells were stained with 1.5–2.0 mg/ml FITC-phalloidin (Sigma Aldrich). At each time point, MFI values were measured by FACS in stimulated and unstimulated MDM. The relative content of F- actin was obtained by subtracting the MFI values of unstimulated cells from the MFI values of stimulated cells.

Polarization assay

Macrophage polarization assay was performed as described (23) with minor modification. Briefly, pre-warmed MDM (106/ml) were stimulated, in duplicates, with chemoattractants or medium alone for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by adding ice-cold phosphate-buffered formaldehyde (10% vol/vol; pH 7.2) and the percentage of cells with a bipolar configuration (front-tail) was determined in at least 200 cells for each tube by phase-contrast microscopy.

Measurements of nitric oxide (NO) and MIF

Due to the very high nitrate levels in RPMI medium, for measurement of NO macrophages were seeded at the concentration of 1 × 106 cell/ml in MEM 10% FCS prior to mock- or HCMV-infection. At the indicated time points after infection culture supernatants were collected and assayed using a Nitrate/Nitrite Colorimetric Assay kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. NO production was quantified by measuring the levels of nitrite and nitrate, the stable oxidation products of NO, in the cell supernatants using the Greiss reaction. For the measurement of MIF, 1 × 106 macrophages/ml were seeded in RPMI 10% FCS prior to mock- or HCMV-infection and at the indicated time points culture supernatants were collected and analyzed by a sandwich ELISA, employing Quantikine kit for human MIF (R&D systems) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Western Blot analysis

MDM were seeded in RPMI 1% FCS at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml and mock- or HCMV-infected with TB40E (MOI of 5). At the indicated time points, culture supernatants were collected, clarified by centrifugation and then concentrated in Centricon-10 concentrators (Amicon, Beverly, MA) according to the operating manual. Concomitantly, the cells were lysed with 100 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40, DTT and protease inhibitors). Concentrated supernatants and cell-associated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA). Human recombinant MIF (10 ng/lane, R&D Systems) was employed as positive control. Membranes were blocked with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 3% dry milk powder and incubated first with anti-MIF goat Ig (R&D Systems) diluted 1:500 and then with rabbit anti-goat IgG peroxidase conjugated (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). A chemioluminescence detection kit (SuperSignal West Dura, Pierce Biotechnology) was employed according to the manufacturer’s instructions as detection method.

Northern Blot analysis

Total RNA was isolated as previously described (13). 5 μg RNA/lane were electrophoresed and then transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannhein, Germany). RNA levels were equalized on the basis of human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) levels. Probes for human GAPDH were amplified and labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) using commercially available primers (Biomol Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and the PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Similarly, a 348 base pair fragment of human MIF cDNA (NCBI Gene bank accession number BC022414) cloned into pENTR (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) was DIG-labeled using the following primers: (sense) 5′–ACAGAATATGCCGATGTTCATCGTAAACACC-3′ and (antisense) 5′-ATCGAATTCTTAGGCGAAGGTGGAGTTGTTCCAGC-3′. Chemioluminescence detection was performed according to the instruction for the use of the CDP-Star chemioluminescence substrate for alkaline phosphatase (Roche).

Immunodepletion of MIF

For each experiment, a total of 100 μg of goat anti-human MIF or goat Ig (R&D Systems) was added to 100 μl of Dynabeads Protein A (Invitrogen), and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The beads were then washed, resuspended in the conditioned supernatants and incubated with slow rotation for 90 min at 4° C. By placing the sample tubes on the magnet, the beads-Ig-MIF complexes were removed from the conditioned supernatants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results was performed using an unpaired, two-tailed Student t test. Differences were considered significant with P < .05.

Results

MDM are highly susceptible to infection by endotheliotropic strains of HCMV and support the lytic viral replicative cycle

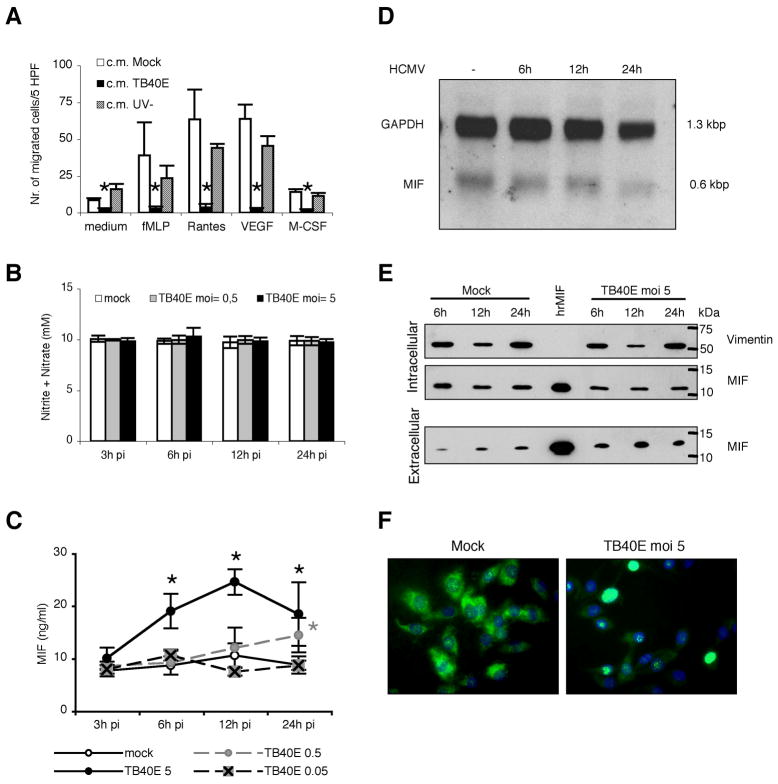

MDM were obtained after 7 days of stimulation of monocytes with M-CSF, which in vivo regulates growth, differentiation and function of many types of tissue macrophages (24). According to Young et al. (17), at the end of the differentiation period, MDM acquire the typical macrophage size and morphology, i.e. giant cells having an elongated or stellate morphology, abundant cytoplasm with granules and vacuoles, and exhibit the expected phenotype concerning expression of surface markers (25) (Table I). Initiation of the viral replicative cycle was evaluated by detection of immediate early antigens (IE 1-2, pUL122/123) in MDM infected with endotheliotropic (TB40E and VHLE) and fibroblast adapted (AD169) strains of HCMV using an MOI of 5. In agreement with findings obtained with other cell types of the myeloid lineage (13,26,27), the infection was efficient with both endotheliotropic strains of HCMV, and at 1 day post infection (p.i.) up to 90% of TB40E-infected MDM were positive for IE antigens (Figure 1A). MDM were poorly susceptible to infection by the fibroblast adapted strain AD169 and less than 5–10% of MDM expressed IE antigens (data not shown). The course of infection was further characterized by kinetic analysis of viral antigen expression, electron microscopy and release of viral progeny. As shown in Figure 1A, viral products characteristic for the subsequent replicative phases (early antigen, p52/UL44 and late antigen, pp150/UL32) were expressed and progressively accumulated in TB40E-infected MDM. The successful completion of the viral cycle was confirmed by detection of an increasing infectivity in both supernatants and cellular fractions of TB40E-infected MDM (Figure 1B), as well as by electron microscopic detection of abundant viral particles in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm of TB40E-infected MDM at 7 days p.i. (data not shown).

Figure 1. Monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) support lytic and productive infection by the HCMV endotheliotropic strain TB40E.

(A) Viral antigens characteristic for the three viral replicative phases are detected by indirect immunofluorescence in macrophages infected with the strain TB40E at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. MDM were stained with mAbs (green staining) specific for the viral immediate-early proteins 1 and 2 (IE 1-2 antigens, pUL122/123), early protein p52 (E antigen, pUL44) and late phosphoprotein pp150 (L antigen, ppUL32) and counterstained with Evans blue (red). All photographs (original magnification × 60) are from one donor representative of ten studied. Mock-infected MDM were negative for viral antigens as shown in the insets. (B) Macrophages were inoculated with TB40E at an MOI of 5 (time point 0) and washed with acid buffer 12 h post infection (p.i.) in order to remove unabsorbed input virus. At the indicated time points, supernatants and cellular fractions were differentially collected for measurement of infectivity by plaque assay.

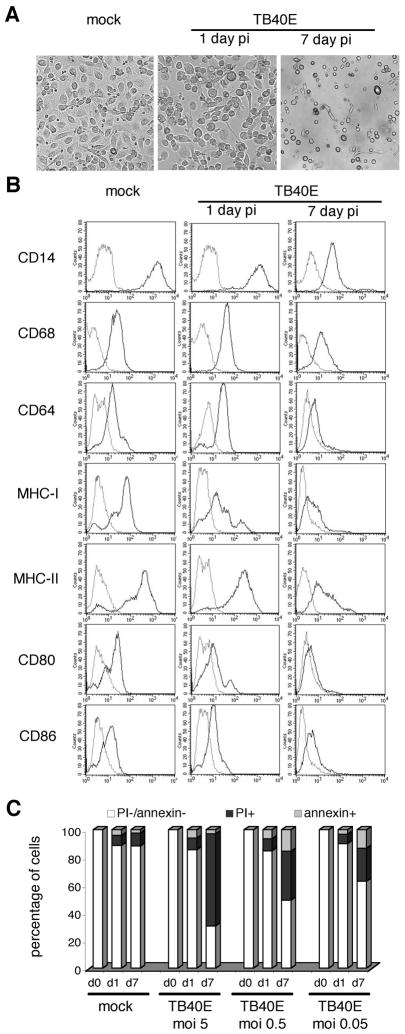

Effect of HCMV infection on the morphology, immunophenotype and viability of MDM

Following HCMV infection, progressive changes were observed in both macrophage morphology and immunophenotype. During the observation period, HCMV-infected MDM enlarged, reduced their substrate adhesion and tended to round up and float in the medium. The viral cytopathic effect became detectable 4 days p.i. with substrate detachment of macrophages and proceeded to an extensive lysis of infected cultures at day 7 after infection (Figure 2A). In addition, while at day 1 p.i. only MHC class I and CD80 were clearly downmodulated on the surface of the majority of TB40E-infected MDM, 7 days p.i. all tested molecules were strongly downregulated as compared to mock-infected cells (Figure 2B). By annexin V/PI staining, we observed that HCMV infection induced MDM death in a dose-dependent manner at late time points after infection. As shown in Figure 2C, while at day 1 p.i. mock- and TB40E-infected MDM exhibited the same levels of PI and annexin V staining, at day 7 p.i. the viability of TB40E-infected MDM decreased proportionally to the MOI used (7 day p.i. MDM infected with an MOI of, 0.05, 0.5 or 5 exhibited a survival of 63% ± 15%, 50% ± 8% and, 31% ± 10%, respectively).

Figure 2. HCMV alters morphology, immunophenotype and viability of MDM.

(A) MDM were mock-infected or infected with TB40E at an MOI of 5 and observed by light microscopy at 1 and 7 days p.i. All photographs (original magnification × 60) are from one donor representative of ten. (B) MDM were mock-infected or infected with TB40E at an MOI of 5 and the immunophenotype was investigated by FACS at 1 and 7 days p.i.. The thick solid lines represent the surface expression of the indicated molecules while the thin lines depict the staining with isotype-matched controls. Representative data from one of five experiments are shown. (C) HCMV infection induces cell death at late time points after infection in a dose-dependent way. Levels of apoptosis (percentage of annexin V positive cells) and necrosis (percentage of propidium iodide (PI) positive cells) were evaluated at day 1 and 7 p.i. in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM, using decreasing MOI from 5 to 0.05 PFU/cell. Representative data from one of five experiments are shown.

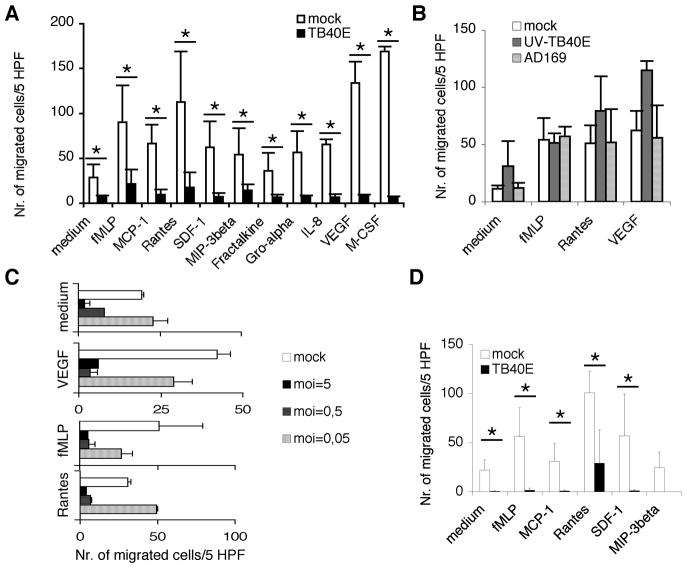

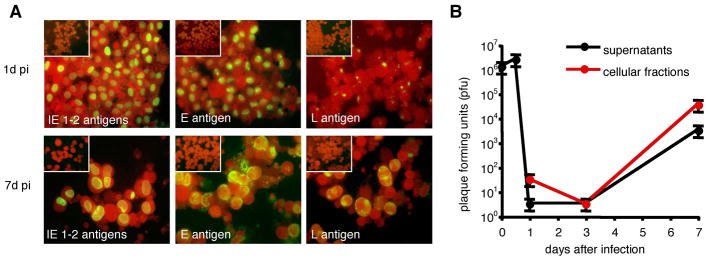

HCMV infection induces a potent inhibition of MDM motility

In order to evaluate the chemotactic responsiveness of HCMV-infected MDM, we measured their migration in response to a wide range of macrophage chemoattractants, such as inflammatory and homeostatic chemokines, growth factors (e.g. VEGF and M-CSF) and a formylpeptide of bacterial origin (fMLP). As shown in Figure 3A, at 24 h p.i. TB40E-infected MDM were unable to migrate in response to all tested stimuli and exhibited a significantly reduced spontaneous basal migration. As mentioned above, at this time point after infection TB40E-infected MDM were neither apoptotic nor necrotic. However, to further ensure that macrophage cellular functionality was intact, we compared the metabolic activity of uninfected and HCMV-infected MDM. By using the tetrazolium salt assay (MTS), we found similar levels of dehydrogenase activity and superoxide formation in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM (absorbance 0.35 ± 0.04 vs. 0.32 ± 0.02, respectively), thus excluding that the effect of HCMV on cell motility was a consequence of cell damage. MDM exposed for 24 h to AD169 or to UV-inactivated TB40E (Figure 3B), which can enter the macrophages but not replicate within these cells, exhibited similar or even increased chemotactic responsiveness than mock-infected MDM. Thus, de novo viral gene expression and not simply virus-cell contact was necessary to block macrophage motility. In detail, the chemotactic responsiveness of TB40E-infected MDM to fMLP, Rantes/CCL5 and VEGF was reduced by 75 ± 10% already at 6 h after infection as compared to uninfected cells (data not shown), suggesting that immediate-early viral genes were responsible for the impairment of MDM migration. In addition, the migration of MDM was inhibited by HCMV in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3C). The block of macrophage migration was persistent and at day 7 p.i. HCMV-infected MDM exhibited a total block of migration (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. HCMV infection induces a potent inhibition of MDM motility.

Macrophage chemotaxis in response to chemokines (Rantes/CCL5, MCP-1/CCL2, Fractalkine/CX3CL1, MIP-3beta/CCL19, Gro-alpha/CXCL1, IL-8/CXCL8 and SDF-1/CXCL12; 100 ng/ml), bacterial product (fMLP; 10−8M) and growth factors (VEGF and M-CSF; 100 ng/ml) was evaluated by using a Boyden chamber as described in the Materials and Methods. Cells were seeded in three wells and for each well the “number of migrated cells” was calculated as “number of cells counted in 5 consecutive high power fields (HPF)”. (A) The migration of mock- or TB40E-infected MDM (MOI of 5) was assessed at 24h p.i.. The numbers of migrated cells/5 HPF are obtained as (mean ± SD) of independent experiments performed with macrophages obtained from ten different blood donors. * P< 0.05 between the two groups. (B) At 24 h p.i. the migration of macrophages incubated with UV-inactivated-TB40E (UV-TB40E) or AD169 (MOI of 5) was compared to the migration of mock-infected MDM. Macrophages were obtained from five different blood donors. (C) MDM were infected with decreasing MOI of TB40E, and at 24h p.i. chemotaxis was evaluated. Macrophages were obtained from three different blood donors. (D) MDM were infected with TB40E at an MOI of 5, and at 7 days p.i. cells were washed, counted and tested for their migratory capacities. The results of four independent experiments (mean ± SD) are shown. * P< 0.05 between the two groups.

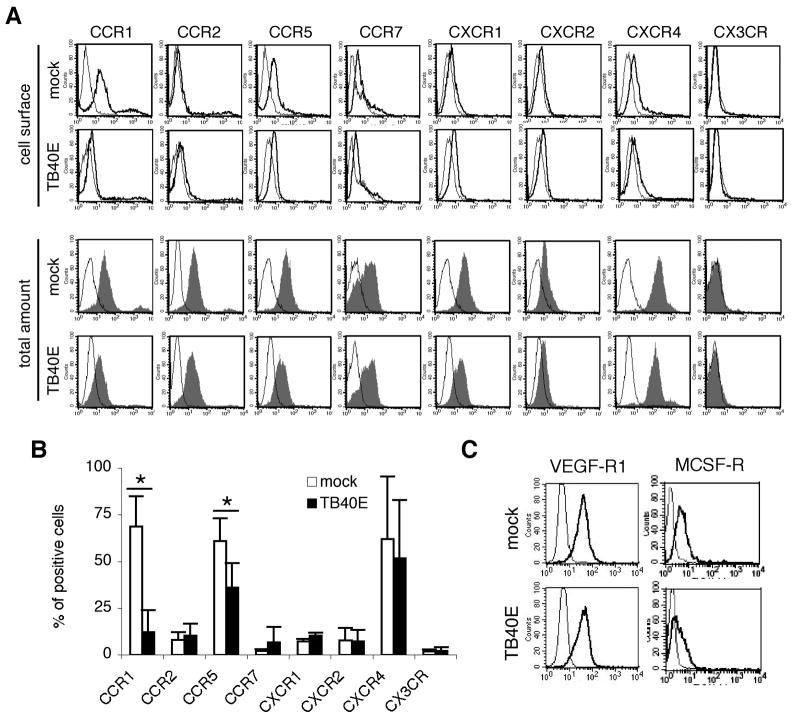

HCMV infection induces intracellular accumulation of CCR1 and CCR5 and downmodulation of their surface levels

Having found that HCMV inhibited migration of MDM, we next analyzed whether HCMV infection could be responsible for the downregulation of cognate receptors. An extensive analysis was performed and both the cell surface and intracellular expression levels of several chemokine and growth factor receptors were investigated in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM. As shown in Figure 4A and B, at day 1 p.i. only the surface expression of CCR1 and CCR5 was significantly reduced in TB40E-infected MDM as compared to mock-infected cells. Conversely, the expression levels of CCR2, CCR7, CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR4 and CX3CR were not affected by HCMV infection, and while CXCR4 was highly expressed in both mock- and TB40E-infected cells, all the other receptors were expressed at low level on the plasmamembrane irrespective of virus incubation. Similarly to the block of migration, the cell surface downregulation of CCR1 and CCR5 was dependent on viral gene expression and MDM exposed to UV-inactivated TB40E (MOI of 5) for 24 h exhibited the same levels of CCR1 and CCR5 than mock-infected cells (data not shown). Furthermore, the total amount of chemokine receptors detectable after cell permeabilization was similar in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM, indicating that upon HCMV infection CCR1 and CCR5 underwent redistribution from the cell surface to an intracellular compartment without being degraded (Figure 4A). Finally, while the expression of VEGF receptor 1 (VEGF-R1 or flt-1) (28) was not affected by HCMV-infection, the levels of MCSF receptor (MCSF-R or CD115) were slightly reduced in TB40E-infected MDM as compared to mock-infected cells (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. HCMV infection selectively modulates the surface expression of certain chemokine and growth factor receptors.

At 1 day p.i., mock- and TB40E-infected MDM (MOI of 5) were harvested, stained for the indicated markers and examined by FACS. (A) Cell surface expression (thick solid lines; intact cells) and total expression (gray-filled curves; permeabilized cells) were evaluated for each chemokine receptor. Thin lines depict staining with isotype-matched control antibodies in intact or permeabilized cells. Representative data from one of ten experiments are shown. (B) The expression of chemokine receptors was measured in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM as percentage of positive cells. Values are mean ± SD of 10 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 (C) Expression of VEGF-R1 and MCSF-R (thick solid lines) on the cell surface of mock- and TB40E-infected MDM. Thin lines depict the staining with isotypic controls. Representative data from one of five experiments are shown.

HCMV infection impairs macrophage polarization and dynamic actin polymerization

Chemotaxis is preceded by cell polarization, an event that occurs within minutes after chemoattractant stimulation and that is marked by formation of cell protrusions and pseudopodia (15). We observed that the capacity of TB40E-infected MDM to polarize in response to stimulation by fMLP, Rantes/CCL5 and VEGF was impaired in a dose- dependent manner (Figure 5A). Following polarization, oriented migration requires rapid assembly and disassembly of actin filaments (15) a phenomenon that can be experimentally followed by measuring the intracellular amount of filamentous [F]-actin upon stimulation with chemoattractants. As shown in Figure 5B, the infection caused a significant impairment of actin assembly and MDM infected with TB40E by using a MOI of 5 showed no increase of F-actin filament content at any time until 15 minutes after stimulation. The block of actin polymerization caused by the virus was dose-dependent and MDM infected with an MOI of 0.05 exhibited a mild inhibition as compared to MDM infected with an MOI of 5.

Figure 5. HCMV infection impairs cellular polarization and actin polymerization in macrophages.

(A) At 1 day p.i., the percentage of cells with bipolar configuration (front-tail) was determined in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM (MOI of 5 and 0.05). The cellular polarization was induced by 10 minutes stimulation with fMLP (10−7M), Rantes/CCL5 (200 ng/ml) or VEGF (500 ng/ml). The results of four independent experiments (mean ± SD) are shown. * P< 0.05. (B) Time course of changes in F-actin content in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM (MOI of 5 and 0.05) stimulated with Rantes/CCL5 (200 ng/ml), fMLP (10−7M) and VEGF (500 ng/ml). The relative F-actin content was evaluated by FITC-phalloidin staining and FACS analysis as described in Materials and Methods.

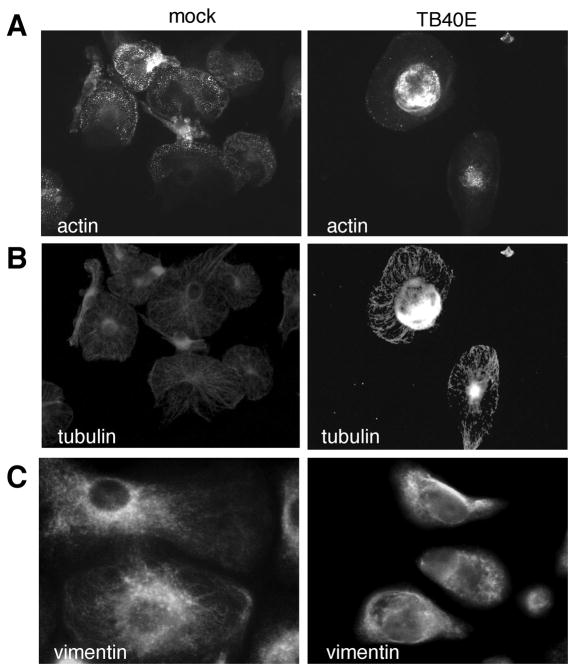

All components of the MDM cytoskeleton are reorganized upon HCMV infection

The impairment of MDM cell polarization and actin polymerization caused by the virus was consistent with the inhibition of cell motility and prompted us to investigate the organization of the cellular cytoskeleton. While in mock-infected MDM actin was organized in abundant and extended podosomes, defined as dot-like cores of actin fibers essential for adhesion and movements (29), in TB40E-infected MDM these structures disappeared and actin aggregated in dense perinuclear cores (Figure 6A). The microtubules and the vimentin network also were changed upon infection (Figure 6B and C, respectively). As compared to uninfected cells, TB40E-infected MDM exhibited a reduced extension and complexity of the tubular network and vimentin filaments. By western blot we determined similar amounts of actin, tubulin as well as vimentin in uninfected and infected MDM (data not shown), suggesting that the dramatic structural reorganization of the MDM cytoskeleton was not paralleled by degradation of the main components of the cytoskeleton.

Figure 6. HCMV infection induces a complete reorganization of the MDM cytoskeleton.

The effect of TB40E infection (MOI of 5) on the structural organization of macrophage cytoskeleton was investigated by indirect immunofluorescence at 1 day p.i.. Staining for actin filaments (A), microtubules (B) and intermediate filaments (C) in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM is shown. The results shown are from one donor representative of five.

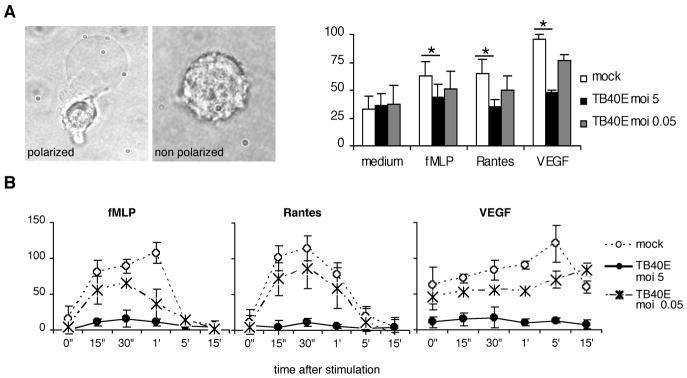

MDM release soluble inhibitors of migration upon HCMV infection

To test whether soluble factors might contribute to the inhibition of migration, uninfected MDM were incubated with virus-free conditioned media (CM) obtained from mock- and TB40E-infected MDM and then used for chemotaxis assays. As shown in Figure 7A, uninfected MDM incubated with CM obtained from TB40E-infected macrophages exhibited impaired migration to all tested stimuli, thus demonstrating that soluble inhibitors were secreted by MDM into the supernatants. As controls, uninfected MDM incubated with CM obtained from mock-infected MDM as well as from MDM treated with UV-inactivated virus (UV-TB40E) exhibited comparable levels of migration thus indicating that only upon HCMV gene expression soluble inhibitors were released. In an attempt to identify the soluble factors responsible for the inhibition of MDM motility, we first focused the attention on nitric oxide (NO), which is known to inhibit cytoskeletal assembly and pseudopodia formation in macrophages (30). By measuring the total amounts of nitrite and nitrate, which accumulate as dead-end products of NO oxidation, we detected identical low levels of NO in the conditioned media obtained from mock- as well as HCMV-infected macrophages (Figure 7B) thus excluding the NO involvement in causing block of cell migration upon HCMV infection. We also measured the secretion of MIF, a soluble product that inhibits random and chemokine-driven migration of macrophages by a mechanism independent of chemokine receptor modulation (31,32). As shown in Figure 7C, HCMV infection stimulated the secretion of MIF into the supernatants in a dose- and time- dependent manner. By using the MOI of 5, we then investigated the MIF gene expression, the MIF total protein amount and its specific localization in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM. As shown in Figure 7D, during the time course of infection the amount of mRNA encoding for MIF remained constant, thus excluding an increased gene transcriptional activity. Secondly, the analysis of the intracellular MIF content of infected and uninfected MDM by western blot revealed that lower levels of MIF were detected in infected cells starting at 6 h p.i.. The decline of intracellular MIF was paralleled by an increase of extracellular MIF, starting at 6 h p.i. and reaching peak levels at 12 h p.i.. By immunofluorescence we confirmed that HCMV induced a differential intracellular localization of MIF (Figure 7F). While in mock-infected MDM MIF was ubiquitously detectable and accumulated in the cytoplasm of all cells, 24 h p.i. the cytoplasm of TB40E-infected MDM appeared empty due to the release of the granules. All together these data confirmed that HCMV infection induced the secretion of MIF from the intracellular stores into the supernatants.

Figure 7. HCMV infection stimulates the secretion of soluble inhibitors in MDM.

(A) Uninfected MDM were treated for 24 h with conditioned media (CM) obtained from mock- and TB40E-infected MDM as well as from MDM treated with UV-inactivated TB40E and migration experiments were performed. CM were collected at 1 day p.i. and prior incubation with uninfected MDM they were filtered in order to remove the viral particles. The results of five independent experiments (mean ± SD) are shown. * P< 0.05 (B) Total nitrate and nitrite production from mock- and TB40E-infected (MOI of 5 and 0.5) MDM. The figure shows the results from four different experiments (mean ± SD). (C) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) release was analyzed by sandwich ELISA of supernatants collected at the indicated time points from mock- and TB40E-infected MDM (MOI of 5, 0.5 and 0.05). The results of five independent experiments (mean ± SD) are shown. * P< 0.05 between mock- and TB40E-infected cells. (D) Northern blot analysis of MIF. MDM were either mock- or TB40E-infected (MOI of 5) for the indicated time points. Blots were probed for MIF (a single 0.6-kb transcript was found) and then reprobed for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The results show MDM from one donor representative of three studied. (E) Western blot analysis of intra- and extra-cellular content of MIF in mock- and TB40E- infected MDM. Cells were mock- or TB40E-infected with an MOI of 5 and collected at the indicated time points after infection. Concentrated supernatants and cell-lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Human recombinant MIF (10 ng/lane) was employed as positive control. (F) At 24 h pi, the intracellular distribution of MIF was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence (green fluorescence) in mock- and TB40E-infected MDM. DAPI staining was used to detect the nuclei. Photographs (original magnification 60x) are from one donor representative of five studied.

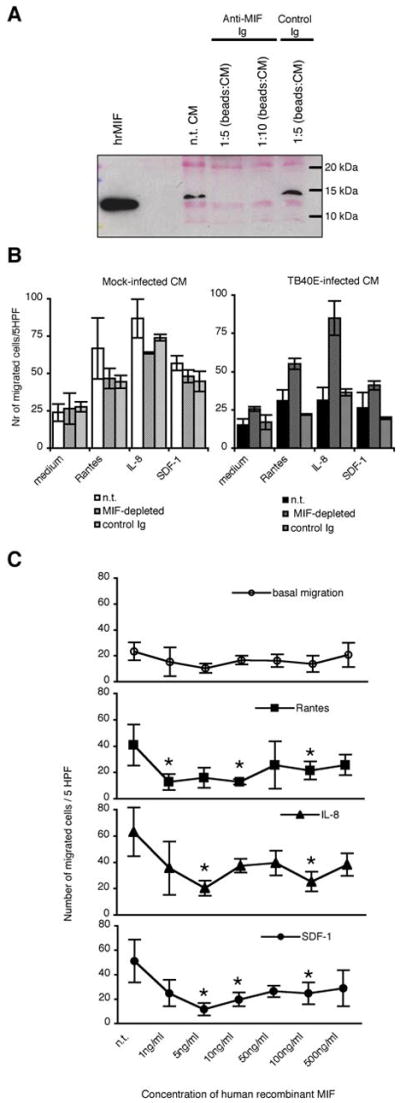

MIF is an important soluble factor responsible for the HCMV-dependent inhibition of cell migration

To investigate whether secreted MIF acts as soluble inhibitor of macrophage chemotaxis in our experimental settings, we immunodepleted MIF from the conditioned media (CM) and then analyzed whether the migration of macrophages was restored. First, we selectively removed MIF from the CM by using beads coated with antibodies directed against MIF or irrelevant control antibodies. As shown in Figure 8A, western blot analysis confirmed that the depletion was efficient. While CM incubated with beads coated with anti-MIF Ig were depleted from MIF, CM incubated with beads coated with control Ig as well as non treated (n.t.) CM still exhibited high amounts of MIF. We then incubated freshly prepared uninfected MDM with CM obtained from TB40E-infected MDM with and without MIF-depletion and measured their migratory capacities. As control, MIF-depletion as well as the control treatment did not effect the migration of cells incubated with supernatants obtained from mock-infected MDM (Figure 8B, left panel). In contrast, the depletion of MIF from the CM obtained from TB40E-infected MDM completely restored the migration of the exposed uninfected MDM (right panel). The inhibitory role of secreted MIF was further verified by using human recombinant MIF (hrMIF, produced as described in (33) and containing 32 endotoxin units/mg of protein). As shown in Figure 8C, the treatment of fresh MDM for 24h with hrMIF partially induced the same effects observed during HCMV infection. In a dose-dependent manner the hrMIF induced the block of migration in response to RANTES/CCL5, IL-8/CXCL8 and SDF-1/CXCL4. The dose-dependent inhibition showed some differences between the different stimuli, however in our experimental setting the optimal dose of hrMIF was 100 ng/ml which is in accord with the original published data (33).

Figure 8. MIF is the soluble factor responsible for the inhibition of MDM migration.

(A) Dynabeads were coated with goat immunoglobulins directed against MIF (Anti-MIF Ig) or not (control Ig) and then incubated with conditioned media (CM) using a ratio vol.beads:vol.CM of 1:5 and 1:10. Depletion of MIF from conditioned media was proved by western blot analysis after supernatant concentration as described in the Materials and Methods. To verify equal loading the Poinceau staining is shown. (B) MDM were incubated for 24 h with virus-free conditioned media obtained from mock- and TB40E-infected cultures and then employed for migration experiments. The conditioned media were left non-treated (n.t.), or were treated with beads coated with anti-MIF (MIF-depleted) or control immunoglobulins (control Ig). The numbers of migrated cells/5 HPF are obtained as (mean ± SD) of independent experiments performed with macrophages obtained from five different blood donors. (C) Inhibition of macrophage migration by human recombinant MIF (hrMIF). Uninfected MDM were incubated for 24 h with increasing amounts (1 – 500 ng/ml) of hrMIF prior measurement of their migratory capacities by using a Boyden chamber. Each point depicts the mean of independently performed experiments with cells obtained from three blood donors.

In conclusion, these results demonstrated that once released into the supernatant MIF was fully functional and efficiently blocked the migration of macrophages.

Discussion

Our study shows that human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) inhibits the chemotaxis of human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) in response to a number of stimuli by employing different strategies. Immediately after entry of HCMV into MDM and onset of viral gene expression, some cellular chemotactic receptors undergo surface downregulation. Furthermore cytoskeleton components are reorganized in dense and rigid structures. Finally, through secretion of soluble inhibitory factors, the block of migration is also assured in the neighboring uninfected macrophages. Importantly, HCMV inhibition of macrophage migration takes place in cells that are viable and metabolically active. The physiological consequences of this inhibition may lead to an impairment of the antiviral response and to a deregulation of the inflammatory microenvironment.

These data complete the analysis of the effects exerted by HCMV on the migratory ability of antigen presenting cells. In our view it is startling that upon HCMV infection not only monocytes (13) and dendritic cells (11,12) but also, as we show now, macrophages undergo an impairment of migration. The molecular mechanisms adopted by HCMV appear to be different in the three cell types and most likely they reflect the high level of HCMV-adaptation to its host.

Although it is well accepted that viral and microbial pathogens can manipulate the macrophage chemotactic machinery for their own benefit, so far the reports describing the effects exerted by pathogens on the general migratory properties of macrophages are few. Beside HCMV, viral infection of macrophages with influenza and herpes simplex viruses markedly depresses the chemotactic responses of these cells (46,47). Similarly, macrophages infected with Salmonella (48) or Toxoplasma (49) exhibit no or reduced motility. It appears clear that the diminished ability of macrophages to respond to chemotactic stimuli is not caused by pathogen-induced cytotoxicity and is not a universal effect. Other pathogens do not affect macrophage motility, such as vaccinia and poliovirus (47). On the contrary, there are infections, such as HIV or Mycobacterium tuberculosis that can even enhance the chemotactic response of macrophages thus promoting the microbial dissemination into other tissues (50–51).

It is generally accepted that HCMV undermines different host immune functions and that virus-induced immunomodulation contributes to persistence and spread of HCMV. A well-documented example is the infection and resulting functional deregulation of dendritic cell maturation, cytokine production, and lymphocyte stimulation capability (34,35). The mechanisms that HCMV exploits to avoid immune eradication often lead to increased inflammation that in turn plays a central role in the viral pathogenesis. An extensive literature indeed indicates that HCMV induces the secretion of a number of inflammatory mediators that in turn may enhance viral replication (36) and reactivation from latency (37). As key cells in the local inflammation (38) and as important site of HCMV reactivation and replication (10,39), macrophages may represent an element where the host inflammatory response and HCMV infection display a synergistic relationship. Macrophages, in contrast to monocytes, exhibit the potential to support HCMV reactivation from latency and viral replication as well as to sustain the host inflammatory response through secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators. Since their regulated migration and spatial distribution in response to environmental signals are prerequisites for mounting an effective antiviral immune response as well as for the limitation of damage and the healing after immune response (40), we decided to investigate the effects exerted by HCMV infection on the macrophage trafficking properties.

In our experimental system, MDM were obtained from monocytes stimulated with M-CSF, which in vivo is one of the main regulators of growth, differentiation and function of many types of tissue macrophages (24). Consistent with findings of Sinzger et al. (27) that however used macrophages differentiated in the presence of GM-CSF, we found that MDM were highly susceptible to HCMV infection and supported the complete replicative viral cycle. As a result of HCMV infection, MDM underwent a complete block of cell migration and became unresponsive to inflammatory and constitutive chemokines, bacterial products and growth factors.

Since it is obvious that virus-induced cell damage might reduce the capacity of infected MDM to migrate, we focused our investigations to the early phase of viral replication. At 24 h p.i., we measured comparably low levels of apoptosis/necrosis as well as similar metabolic activities in mock- and HCMV-infected MDM, thus excluding that the inhibition of cell migration was simply due to impending cell death or cell injury. Cell migration is a highly integrated multistep process that is triggered by the presence of chemoattractants. Chemokines, bacterial products, and growth factors are sensed by receptors expressed on the cell surface. In accordance with the high motility exhibited by mock-infected MDM, we measured high levels of chemokine (i.e. CCR1, CCR2, CXCR4) and growth factor receptors (VEGF-R and MCSF-R) on the plasmamembrane of uninfected MDM. Low responsiveness of MDM to Gro-alpha, IL-8 and MIP-3beta was reflected by the low surface levels of CXCR1, CXCR2 and CCR7. After HCMV infection, the expression pattern of chemotactic receptors was only partially affected. On the cell surface of TB40E-infected MDM only CCR1 and CCR5 were clearly downregulated whereas CXCR4, VEGF-R1 and MCSF-R were maintained at high levels. The restricted viral effect on the expression of chemotactic receptors and the observation that the basal MDM migration was also impaired upon infection prompted us to examine the effect of HCMV infection on the properties of the cellular cytoskeleton.

We observed that the cell polarization in response to chemotactic stimulation was inhibited by HCMV in a dose-dependent manner. While mock-infected MDM exhibited large ruffling lamellipodia on one side of the cell and a conical tail at the opposite side, HCMV-infected MDM remained round and possessed only few membrane protrusions. The defective morphological polarization was mirrored by a potent inhibition of actin polymerization, which normally drives and maintains the formation of cell membrane protrusions. HCMV-infected MDM did not assembly actin filament in response to stimulation and presented completely altered cytoskeleton architecture. The delicate organization of actin in punctuated rings concentrate at the substrate interface as well as the radially oriented microtubular network disappeared after HCMV infection. These modifications are not associated with cell death (41), but since microtubules and actin filaments functionally cooperate in generating cell migration, we believe that the observed cytoskeletal modifications in HCMV-infected MDM represent a mechanism for the inhibition of chemotaxis and chemokinesis.

As additional proof of extreme sophistication and optimized host-adaptation, HCMV displays the capacity to impair the migration of uninfected neighboring cells through the release of soluble inhibitors. In the supernatants of HCMV-infected MDM we measured increased amounts of MIF, a pleiotropic cytokine that has been shown to inhibit macrophage migration (32), and to potently stimulate the production of proinflammatory mediators (42). We performed a large number of experiments to confirm the physiologic role of MIF as soluble inhibitor of MDM chemotaxis and we adopted different approaches. Blocking antibodies directed against MIF (21), the chemical inhibitor ISO-1 (43) and the secretion inhibitor Probenecid (44) were used to specifically inhibit the function of MIF in the conditioned supernatants produced by HCMV-infected MDM. The results obtained with these inhibitors supported the role of MIF as soluble inhibitor but were not definitive, most likely due to an incomplete binding of the Ab- or functional blockade by the chemical drugs. Finally, by depleting native MIF from the conditioned media and measuring the restoration of cell migration we were able to show that once released from HCMV-infected MDM MIF is fully functional and responsible for inhibition of macrophage migration.

In conclusion, we observed that HCMV affects MDM properties at different levels. Upon HCMV infection macrophages are immobilized through dramatic cytoskeletal reorganization and the downregulation of CCR1 and CCR5. Concomitantly, HCMV-infected MDM are activated to secrete MIF that in turn acts as an inhibitor of migration for neighboring cells. It is important to keep in mind that during HCMV infection, viral particles and MIF simultaneously stimulate the macrophages thus rendering extremely difficult the distinction between the effects directly mediated by viral gene expression and those induced by MIF. Nevertheless, by using hrMIF, we observed an impairment of MDM motility that partially mimicked the block of migration induced by HCMV. Interestingly, MDM treated with hrMIF did not expressed reduced levels of CCR1 and CCR5 as viral-infected cells do, but only exhibited decreased expression levels of CXCR4. Our results are in agreement with a recent study (45) showing that MIF can act as a chemokine-like mediator and desensitize CXCR4 and CXCR2. However, this activity does not entirely explain the effect of HCMV infection as we did not observe downregulation of CXCR4 or CXCR2 in HCMV-infected MDM. We believe that during HCMV infection various mediators or signaling pathways can influence the biologic properties of MIF and lead to additional effects such as alteration of the cytoskeletal machinery.

We propose that our in vitro findings may have important clinical implications in chronic inflammatory diseases with locally active HCMV infection. We suggest that once tissue macrophages are recruited into the area of HCMV replication, they quickly loose responsiveness to chemoattractants and are retained in situ. These cells could provide sites for viral replication and MIF production that by triggering the secretion of pro-inflammatory factors in surrounding cells ultimately exacerbates episodes of acute inflammation.

Hence, the interference of HCMV with the migratory ability of MDM may alter macrophage trafficking and contribute to viral immune evasion, but may also contribute to boost already existing inflammatory conditions and viral persistence in the organism.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Anke Lüske for the excellent viral stock preparations and Ingrid Bennett for critical reading.

Abbreviation used in this paper

- HCMV

human cytomegalovirus

- MDM

monocyte-derived macrophages

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- p.i

post infection

- MIF

macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- CM

conditioned media

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Bucala is a co-inventor on a patent describing the therapeutic benefit of anti-MIF.

Reference List

- 1.Stoy N. Macrophage biology and pathobiology in the evolution of immune responses: a functional analysis. Pathobiology. 2001;69:179–211. doi: 10.1159/000055944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross JAK, Auger MJ, Hamilton TA, Paglia P, Colombo MP, Zink W, Ryan L, Gendelman HE, Heale J-P, Speert DP, Vray B, Carlson KA, Cotter RL, Williams CE, Branecki CE, Zheng J, Yoon J-W, Jun H-S, Breshnihan B, Youssef P, Dipietro LA, Strieter RM, Kreutz M, Fritsche J, Andreesen R, Jessup W, Baoutina A, Kritharides L, Matyszak MK, Perry VH, Okamura H, Katabuchi H, Kanzaki H, Burke B, Sumner S, Mahon PC, Lewis CE, Byrne HM, Owen MR. The Macrophage. Oxford University Press Inc; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocarski ES., Jr Immunomodulation by cytomegaloviruses: manipulative strategies beyond evasion. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soderberg-Naucler C. Does cytomegalovirus play a causative role in the development of various inflammatory diseases and cancer? J Intern Med. 2006;259:219–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu R, Moroi M, Yamamoto M, Kubota T, Ono T, Funatsu A, Komatsu H, Tsuji T, Hara H, Hara H, Nakamura M, Hirai H, Yamaguchi T. Presence and Severity of Chlamydia pneumoniae and Cytomegalovirus Infection in Coronary Plaques Are Associated With Acute Coronary Syndromes. Int Heart J. 2006;47:511–519. doi: 10.1536/ihj.47.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahbar A, Bostrom L, Lagerstedt U, Magnusson I, Soderberg-Naucler C, Sundqvist VA. Evidence of active cytomegalovirus infection and increased production of IL-6 in tissue specimens obtained from patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:154–161. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehraein Y, Lennerz C, Ehlhardt S, Remberger K, Ojak A, Zang KD. Latent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in synovial tissue of autoimmune chronic arthritis determined by RNA- and DNA-in situ hybridization. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:781–789. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz F, Urkijo JC, Mendoza F, De l, Blanco VM, Flores M, Berdonces P. Systemic lupus erythematosus associated with acute cytomegalovirus infection. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006;12:263264. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000239832.74804.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons JG, Borysiewicz LK, Sinclair JH. Monocytes are a major site of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2059–2064. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinzger C, Plachter B, Grefte A, The TH, Jahn G. Tissue macrophages are infected by human cytomegalovirus in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:240–245. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moutaftsi M, Brennan P, Spector SA, Tabi Z. Impaired lymphoid chemokine-mediated migration due to a block on the chemokine receptor switch in human cytomegalovirus-infected dendritic cells. J Virol. 2004;78:3046–3054. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3046-3054.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varani S, Frascaroli G, Homman-Loudiyi M, Feld S, Landini MP, Soderberg-Naucler C. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits the migration of immature dendritic cells by down-regulating cell-surface CCR1 and CCR5. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:219–228. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frascaroli G, Varani S, Moepps B, Sinzger C, Landini MP, Mertens T. Human cytomegalovirus subverts the functions of monocytes, impairing chemokine-mediated migration and leukocyte recruitment. J Virol. 2006;80:7578–7589. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02421-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zicha D, Allen WE, Brickell PM, Kinnon C, Dunn GA, Jones GE, Thrasher AJ. Chemotaxis of macrophages is abolished in the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Br J Haematol. 1998;101:659–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young DA, Lowe LD, Clark SC. Comparison of the effects of IL-3, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor in supporting monocyte differentiation in culture. Analysis of macrophage antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 1990;145:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodwin CJ, Holt SJ, Downes S, Marshall NJ. Microculture tetrazolium assays: a comparison between two new tetrazolium salts, XTT and MTS. J Immunol Methods. 1995;179:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodrum F, Jordan CT, Terhune SS, High K, Shenk T. Differential outcomes of human cytomegalovirus infection in primitive hematopoietic cell subpopulations. Blood. 2004;104:687–695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wentworth BB, French L. Plaque assay of cytomegalovirus strains of human origin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1970;135:253–258. doi: 10.3181/00379727-135-35031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bacher M, Eickmann M, Schrader J, Gemsa D, Heiske A. Human cytomegalovirus-mediated induction of MIF in fibroblasts. Virology. 2002;299:32–37. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sozzani S, Ghezzi S, Iannolo G, Luini W, Borsatti A, Polentarutti N, Sica A, Locati M, Mackay C, Wells TN, Biswas P, Vicenzi E, Poli G, Mantovani A. Interleukin 10 increases CCR5 expression and HIV infection in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:439–444. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang JM, Cianciolo GJ, Snyderman R, Mantovani A. Coexistence of a chemotactic factor and a retroviral P15E-related chemotaxis inhibitor in human tumor cell culture supernatants. J Immunol. 1986;137:2726–2732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naito M, Umeda S, Takahashi K, Shultz LD. Macrophage differentiation and granulomatous inflammation in osteopetrotic mice (op/op) defective in the production of CSF-1. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46:85–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199701)46:1<85::AID-MRD13>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akagawa KS. Functional heterogeneity of colony-stimulating factor-induced human monocyte-derived macrophages. Int J Hematol. 2002;76:27–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02982715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riegler S, Hebart H, Einsele H, Brossart P, Jahn G, Sinzger C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells are permissive to the complete replicative cycle of human cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:393–399. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinzger C, Eberhardt K, Cavignac Y, Weinstock C, Kessler T, Jahn G, Davignon JL. Macrophage cultures are susceptible to lytic productive infection by endothelial-cell-propagated human cytomegalovirus strains and present viral IE1 protein to CD4+ T cells despite late downregulation of MHC class II molecules. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1853–1862. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barleon B, Sozzani S, Zhou D, Weich HA, Mantovani A, Marme D. Migration of human monocytes in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated via the VEGF receptor flt-1. Blood. 1996;87:3336–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linder S, Aepfelbacher M. Podosomes: adhesion hot-spots of invasive cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:376–385. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jun CD, Han MK, Kim UH, Chung HT. Nitric oxide induces ADP-ribosylation of actin in murine macrophages: association with the inhibition of pseudopodia formation, phagocytic activity, and adherence on a laminin substratum. Cell Immunol. 1996;174:25–34. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiser WY, Temple PA, Witek-Giannotti JS, Remold HG, Clark SC, David JR. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding a human macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7522–7526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermanowski-Vosatka A, Mundt SS, Ayala JM, Goyal S, Hanlon WA, Czerwinski RM, Wright SD, Whitman CP. Enzymatically inactive macrophage migration inhibitory factor inhibits monocyte chemotaxis and random migration. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12841–12849. doi: 10.1021/bi991352p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernhagen J, Mitchell RA, Calandra T, Voelter W, Cerami A, Bucala R. Purification, bioactivity, and secondary structure analysis of mouse and human macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) Biochemistry. 1994;33:14144–14155. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raftery MJ, Schwab M, Eibert SM, Samstag Y, Walczak H, Schonrich G. Targeting the function of mature dendritic cells by human cytomegalovirus: a multilayered viral defense strategy. Immunity. 2001;15:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grigoleit U, Riegler S, Einsele H, Laib SK, Jahn G, Hebart H, Brossart P, Frank F, Sinzger C. Human cytomegalovirus induces a direct inhibitory effect on antigen presentation by monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:189–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soderberg-Naucler C, Fish KN, Nelson JA. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha specifically induce formation of cytomegalovirus-permissive monocyte-derived macrophages that are refractory to the antiviral activity of these cytokines. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3154–3163. doi: 10.1172/JCI119871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hummel M, Zhang Z, Yan S, DePlaen I, Golia P, Varghese T, Thomas G, Abecassis MI. Allogeneic transplantation induces expression of cytomegalovirus immediate-early genes in vivo: a model for reactivation from latency. J Virol. 2001;75:4814–4822. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4814-4822.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van FR, Cohn ZA. The origin and kinetics of mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1968;128:415–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soderberg-Naucler C, Streblow DN, Fish Jlan-Yorke KN, Smith PP, Nelson JA. Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus in CD14(+) monocytes is differentiation dependent. J Virol. 2001;75:7543–7554. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7543-7554.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellingan GJ, Caldwell H, Howie SE, Dransfield I, Haslett C. In vivo fate of the inflammatory macrophage during the resolution of inflammation: inflammatory macrophages do not die locally, but emigrate to the draining lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1996;157:2577–2585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fish KN, Britt W, Nelson JA. A novel mechanism for persistence of human cytomegalovirus in macrophages. J Virol. 1996;70:1855–1862. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1855-1862.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calandra T, Bernhagen J, Metz CN, Spiegel LA, Bacher M, Donnelly T, Cerami A, Bucala R. MIF as a glucocorticoid-induced modulator of cytokine production. Nature. 1995;377:68–71. doi: 10.1038/377068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lubetsky JB, Dios A, Han J, Aljabari B, Ruzsicska B, Mitchell R, Lolis E, Al-Abed Y. The tautomerase active site of macrophage migration inhibitory factor is a potential target for discovery of novel anti-inflammatory agents. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24976–24982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flieger O, Engling A, Bucala R, Lue H, Nickel W, Bernhagen J. Regulated secretion of macrophage migration inhibitory factor is mediated by a non-classical pathway involving an ABC transporter. FEBS Lett. 2003;551:78–86. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernhagen J, Krohn R, Lue H, Gregory JL, Zernecke A, Koenen RR, Dewor M, Georgiev I, Schober A, Leng L, Kooistra T, Fingerle-Rowson G, Ghezzi P, Kleemann R, McColl SR, Bucala R, Hickey MJ, Weber C. MIF is a noncognate ligand of CXC chemokine receptors in inflammatory and atherogenic cell recruitment. Nat Med. 2007;13:587–596. doi: 10.1038/nm1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salentin R, Gemsa D, Sprenger H, Kaufmann A. Chemokine receptor expression and chemotactic responsiveness of human monocytes after influenza A virus infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:252–259. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1102565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleinerman ES, Daniels CA, Polisson RP, Snyderman R. Effect of virus infection on the inflammatory response. Depression of macrophage accumulation in influenza-infected mice. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:373–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao C, Wood MW, Galyov EE, Höpken UE, Lipp M, Bodmer HC, Tough DF, Carter RW. Salmonella typhimurium infection triggers dendritic cells and macrophages to adopt distinct migration patterns in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2939–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Da Gama LM, Ribeiro-Gomes FL, Guimarães U, Jr, Arnholdt AC. Reduction in adhesiveness to extracellular matrix components, modulation of adhesion molecules and in vivo migration of murine macrophages infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:1287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ibarrondo FJ, Choi R, Geng YZ, Canon J, Rey O, Baldwin GC, Krogstad P. HIV type 1 Gag and nucleocapsid proteins: cytoskeletal localization and effects on cell motility. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1489–1500. doi: 10.1089/08892220152644197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stegelmann F, Bastian M, Swoboda K, Bhat R, Kiessler V, Krensky AM, Roellinghoff M, Modlin RL, Stenger S. Coordinate expression of CC chemokine ligand 5, granulysin, and perforin in CD8+ T cells provides a host defense mechanism against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2005;175:7474–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]