Abstract

A patient was admitted as an emergency with bowel obstruction. Recent medical history included an episode of gallstone ileus treated surgically by removal of an enteric calculus. On this admission, an obstructing calculus was removed from the descending colon (gallstone coleus) at laparotomy. However, the postoperative course was complicated by sepsis and the patient died. A CT scan on the second admission and cytology results from a liver abscess suggested gallbladder malignancy as the underlying cause of the cholecystoenteric fistula. The technical challenge and increased mortality associated with cholecystoenteric fistula repair supports simple enterolithotomy as the preferred management of gallstone ileus. However, this case supports the need for a systematic search for all enteric stones at laparotomy and consideration of concurrent or interval cholecystectomy and cholecystoenteric fistula repair to prevent recurrent gallstone ileus and determine underlying pathology.

Background

Gallstone ileus, first described by Bartholin in 1654,1 occurs when one or more gallstones become impacted in the lumen of the intestine. Prior formation of a cholecystoenteric fistula is common and usually results from gallstone perforation of the duodenum or colon2 often secondary to cholecystitis or rarely malignancy. Once a gallstone is present within the gastrointestinal tract, the majority passes spontaneously yet a small number will become impacted. Obstructing stones often impact in the ileum where the lumen is narrowest and peristalsis is weaker.3 Surgical intervention is associated with significant mortality3 and recurrent gallstone ileus is rare.4 It is therefore argued that in the presence of increasing age or significant comorbidity, relief of obstruction by simple enterolithotomy alone is justified.4 The need for biliary surgery at a later date is debated and should consider patient's comorbidity and the presence of persisting symptoms or residual stones.4 This paper describes a case of gallstone ileus and gallstone coleus; the presence of gallstones causing small bowel obstruction and subsequently large bowel obstruction in the same patient.

Case presentation

A female patient in her 70s presented twice with bowel obstruction. On the first admission, CT scan demonstrated multiple gallstones, aerobilia, small bowel obstruction and two calculi within the small bowel (figure 1). The patient underwent laparotomy and retrieval of a single gallstone from the distal jejunum via longitudinal enterotomy. However, a systematic search of the small and large bowel was not made and the second gallstone was not located. Following discharge the patient was subsequently seen in the outpatient clinic. Although symptom free, she reported poor mobility and exercise tolerance and on examination was morbidly obese (weight 118 kg, body mass index 51.1 kg/m2). On anaesthetic assessment she was given an American Society of Anaesthesiologists score of 3. As a result, an interval cholecystectomy and cholecystoenteric fistula repair was considered too risky.

Figure 1.

CT image demonstrating dilated small bowel loops and two calculi with the small intestine (solid arrow, obstructing calculi and dotted arrow, non-obstructing calculi).

Four months later, the patient presented with a week's history of colicky abdominal pain and vomiting. On examination, the patient was found to be distressed with abdominal distension and generalised tenderness with a tender incisional hernia from her previous laparotomy.

Investigations

Plain abdominal radiography revealed small and large bowel obstructions. Laboratory investigations revealed raised inflammatory markers (white cell count of 14×109/l and C reactive protein 81 mg/l) and acute renal failure (creatine 203 μmol/l and urea 39 mmol/l). Liver function tests were mildly deranged (bilirubin 21 µmol/l, alkaline phosphatase 137 IU/l and alanine transaminase 65 IU/l) and the amylase was not raised (55 IU/l).

Differential diagnosis

The bowel obstruction was presumed to be because of the patient's incisional hernia. The differential diagnosis of recurrent gallstone obstruction was not documented and a CT was not performed at this time.

Treatment

A decision was taken to repair the umbilical hernia yet at operation the hernia was found to contain only fat and no bowel. Postoperatively the bowel obstruction persisted and a CT scan was performed which revealed a 3 cm opacity in the distal descending colon with large and small bowel obstructions (figure 2). The CT also demonstrated a cholecystoduodenal fistula, with the suggestion of cholangiocarcinoma and lesions within the liver suggestive of metastatic deposits. In order to avoid a general anaesthetic, a flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed yet while this demonstrated diverticular disease it failed to remove the stone or decompress the obstructed colon. A subsequent laparotomy was therefore performed and an obstructing calculus was removed via a colonic enterotomy. Given the patient's comorbidity and deteriorating physiology, a decision was taken not to perform concurrent cholecystectomy or cholecystoenteric fistula repair.

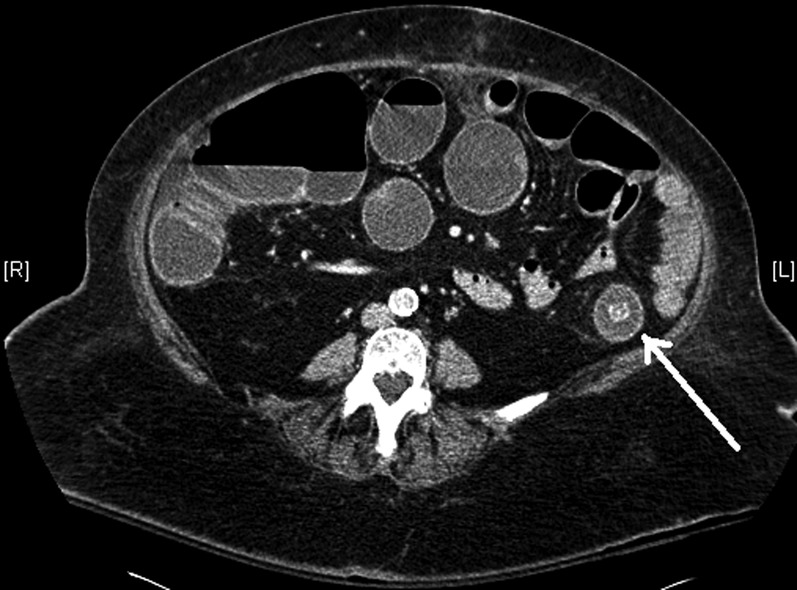

Figure 2.

CT image demonstrating dilated caecum and small bowel loops with obstructing calculi in descending colon (arrow).

Outcome and follow-up

The postoperative period was complicated by acute renal failure, a pulmonary embolus and ongoing sepsis. Cytology from a liver abscess that was drained confirmed the presence of an underlying malignant process. Despite intensive organ support the patient's clinical condition deteriorated and the patient died.

Discussion

In this paper we describe a case of gallstone ileus which was managed by simple enterolithotomy. Despite the finding of a second stone on preoperative imaging, further calculi were not retrieved, or fistula repair or cholecystectomy was performed. Four months later, the same patient developed large bowel obstruction and underwent enterolithotomy of an obstructing colonic calculus. The presence of an underlying gallbladder carcinoma with hepatic metastases was suggested by preoperative imaging and postoperative cytology results.

Gallstone ileus is relatively rare but recognised complication of cholelithiasis and cause intestinal obstruction. Hospital episode statistics report almost 2000 emergency admissions with gallstone ileus in England over the last 10 years.5 Migration of a gallstone through a cholecystoenteric fistula, most commonly cholecystoduodenal, and subsequent impaction in the distal ileum is described in majority of the cases.4 Enterobiliary fistulae commonly form following acute cholecystitis with formation and subsequent perforation of cholecystoenteric adhesions. Cholecystocolonic fistula, often at the hepatic flexure, account for a small proportion of cholecystoenteric fistulae and are more frequently seen in the elderly and females.6 Such fistulae commonly present with diarrhoea or ascending cholangitis, with mechanical large bowel obstruction rare given the calibre of the colon. Obstruction may occur within the sigmoid colon, however,7 at a point of pathological narrowing resulting from diverticular disease8 or previous pelvic irradiation.9

Recurrent gallstone ileus is thought to be rare. However, the presence of second or multiple stones may be as high as 5%.10 Enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy and fistula repair performed as a one-stage procedure increases operative mortality, which for simple enterolithotomy alone is approximately 11%10 and is argued by a number of authors to be unnecessary.10 11

The technical challenge of fistula repair and cholecystectomy in the presence of a dense inflammatory process and the reported spontaneous closure of fistulae would support this approach.12 However, the risk of recurrent gallstone ileus or biliary complications supports the one-stage procedure as the procedure of choice. Another reason for immediate or interval cholecystectomy and fistula repair is that a persisting cholecystoenteric fistula may represent an underlying malignant process. Alternatively a chronic cholecystoenteric fistula may predispose to the development of gallbladder malignancy and groups have reported a 15% incidence of gallbladder carcinoma in patients with a persisting cholecystoenteric fistula.13 Therefore, where imaging studies are suspicious for a malignant process or the cholecystoenteric fistula fails to heal spontaneously, further investigation and surgery must be considered.

We believe our case to be one of the first reported instances of gallstone ileus, followed by gallstone coleus. This case questions the safety of a simple enterolithotomy approach in a patient with multiple further gallstones in the gallbladder. In addition, the possibility of an underlying malignant process supports further investigation or intervention following an episode of gallstone ileus.

The course of events in this case is not clear. Undoubtedly initial gallstone ileus occurred secondary to a cholecystoduodenal fistula. It is not clear whether the ultimate diagnosis of malignant process drove the fistula formation, or whether the fistula predisposed to a malignant change. At initial laparotomy a gallstone was removed from the distal jejunum yet a stone was seen in the distal ileum on preoperative imaging and we know that this is the most common site for gallstone obstruction. A systematic search should be performed intraoperatively by ‘running’ the bowel between the surgeon's fingers from the duodenojejunal flexure to the sigmoid colon. In addition, postoperative or interval cross-sectional imaging could be performed to demonstrate the presence of persisting enteric calculi. In this case, it is probable that the ‘missed’ second stone travelled distally and went on to cause the subsequent large bowel obstruction. Alternatively a synchronous or subsequent cholecystocolonic fistula may have been present although this was not identified on imaging studies.

This case provides a number of important lessons that have been discussed at the local morbidity and mortality meeting but that warrant wider emphasis. First, that recurrent gallstone ileus and gallstone coleus can occur and so on initial laparotomy for gallstone ileus, meticulous and documented examination of the small and large bowel for a second gallstone should be performed. Second, that in a patient with multiple gallstones or a suspicion of underlying malignancy and an episode of gallstone ileus, concurrent or interval cholecystectomy and cholecystoenteric fistula repair should be considered to prevent recurrent gallstone ileus or coleus, or a missed malignancy.

Learning points.

In a patient with gallstone ileus, laparotomy should involve a systematic and meticulous search for the presence of further enteric stones.

Consideration should be given to concurrent or interval cholecystectomy and cholecystoenteric fistula repair to prevent recurrent gallstone ileus.

Consideration and appropriate investigation of the possibility of an underlying malignancy should occur in patients with gallstone ileus.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Martin F. Intestinal obstruction due to gallstones. Ann Surg 1912;55:725–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser AM. Gallstone ileus. N Engl J Med 1997;336:879–80; author reply 80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavien PA, Richon J, Burgan S, et al. Gallstone ileus. Br J Surg 1990; 77:737–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravikumar R, Williams JG. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:279–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hospital Episode Statistics The primary diagnosis: 4-character table. The NHS Information Centre of Health and Social Care, 2011. http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk (accessed 5 Jun 2011)

- 6.Hession PR, Rawlinson J, Hall JR, et al. The clinical and radiological features of cholecystocolic fistulae. Br J Radiol 1996;69:804–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranga N. Large bowel and small bowel obstruction due to gallstones in the same patient. BMJ Case Rep 2011 Apr 26;2011. pii: bcr0920103372. doi: 10.1136/bcr.09.2010.3372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown C. Colonic obstruction due to a gallstone. Br J Clin Pract 1972;26:175–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikura H, Sakata A, Kimura S, et al. Gallstone ileus of the colon. Surgery 2005;138:540–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg 1994;60:441–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayantunde AA, Agrawal A. Gallstone ileus: diagnosis and management. World J Surg 2007;31:1292–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okubo H, Nogawa T, Jibiki M. A case of gallstone ileus which the cholecystoduodenal fistula closed spontaneously after laparoscopic-assisted simple enterolithotomy. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 2006; 103:1157–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossart PA, Patterson AH, Zintel HA. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. A report of seventy-six cases. Am J Surg 1962;103:366–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]