Abstract

Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) such as dieldrin are a persistent class of aquatic pollutants that cause adverse neurological and reproductive effects in vertebrates. In this study, female and male largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) (LMB) were exposed to 3 mg dieldrin/kg feed in a 2 month feeding exposure (August–October) to (1) determine if the hypothalamic transcript responses to dieldrin were conserved between the sexes; (2) characterize cell signaling cascades underlying dieldrin neurotoxicity; and (3) determine whether or not co-feeding with 17β-estradiol (E2), a hormone with neuroprotective roles, mitigates responses in males to dieldrin. Despite also being a weak estrogen, dieldrin treatments did not elicit changes in reproductive endpoints (e.g. gonadosomatic index, vitellogenin, or plasma E2). Sub-network (SNEA) and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that neuro-hormone networks, neurotransmitter and nuclear receptor signaling, and the activin signaling network were altered by dieldrin exposure. Most striking was that the majority of cell pathways identified by the gene set enrichment were significantly increased in females while the majority of cell pathways were significantly decreased in males fed dieldrin. These data suggest that (1) there are sexually dimorphic responses in the teleost hypothalamus; (2) neurotransmitter systems are a target of dieldrin at the transcriptomics level; and (3) males co-fed dieldrin and E2 had the fewest numbers of genes and cell pathways altered in the hypothalamus, suggesting that E2 may mitigate the effects of dieldrin in the central nervous system.

Keywords: Sub-network enrichment analysis, Neuroendocrine, Activin, Steroidgenic-factor-1, Estrogen receptor

1. Introduction

Dieldrin (1,2,3,4,10,10-hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4a,5,67,8,8a-octahydro-1,4,5,8-dimethanonaphthalene) is a neuroactive organochlorine pesticide (OCP) that is a persistent organic pollutant found primarily in sediment in aquatic habitats. Despite restricted use in recent years, dieldrin remains a concern for aquatic organisms such as teleost fishes because there is a high capacity for dieldrin to bioaccumulate in tissues. This has been demonstrated for fish exposed in the laboratory (Lamai et al., 1999; Satyanarayan et al., 2005) and for fish exposed in the natural environment (Johnson et al., 2007; Blocksom et al., 2010). There are also human health concerns surrounding dieldrin that are based upon epidemiological and neurophysiological evidence. Exposure to dieldrin may be associated with increased risk for the progression of human neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease (Fleming et al., 1994; Kanthasamy et al., 2005, 2008; Weisskopf et al., 2010), although a direct causative effect remains difficult to ascertain.

In the context of neurodegenerative diseases, there exist sex differences within the vertebrate brain that may contribute to increased risks to neurodegeneration (Schultz et al., 1996). Neurotransmitter systems (GABA, dopamine, and serotonin) show differences throughout the male and female brain, and serotonin levels and receptors are higher in abundance in females compared to males (Cosgrove et al., 2007). This is also the case for many brain structures and nuclei. Specifically within the hypothalamus, studies report that the infundibular nucleus (INF), an important regulator of neuroendocrine function in the mediobasal hypothalamus, can exhibit sex dependent neurofibrillary pathology which is more prevalent in men than woman with neurodegenerative diseases (Schultz et al., 1999). Lastly, in the mammalian hypothalamus, there is evidence that gene expression patterns show sexual dimorphism with aging, one of the risk factors for neurodegeneration (Berchtold et al., 2008). Males show more changes in gene expression compared to females in the somatosensory cortex, superior frontal gyrus, and entorhinal cortex which is associated with a down regulation of genes in males that are related to protein processing and energy generation. The molecular basis for sex differences in the vertebrate brain are not completely understood and continued exploration into the relationship between sex, exposure to chemicals in the environment, and neurological disease etiology is warranted.

The primary mechanism of action of dieldrin is antagonism of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor, blocking inhibitory GABAergic synaptic transmission in the vertebrate central nervous system (Lawrence and Casida, 1984; Gant et al., 1987). There is also evidence that dieldrin can act as a weak estrogen by binding estrogen receptors (ERs) in mammals (Lemaire et al., 2006) and activating Esr1 in fish (Weil and Denslow, unpubl. data). Thus, the molecular and physiological responses regulated by dieldrin can be multi-modal, involving both direct modulation of GABAergic synaptic transmission in the central nervous system (CNS) and ER signaling cascades.

Genomic and proteomic responses in the teleostean hypothalamus to dieldrin have been investigated previously in reproductively mature female and male largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) (LMB). In an acute exposure, female LMB injected with 10 mg dieldrin/kg and sacrificed after seven days showed a 20–30% increase in GABA levels in the hypothalamus and cerebellum after injection, suggestive of a compensatory mechanism for dieldrinmediated GABAA receptor antagonism (Martyniuk et al., 2010a). In the same study, functional enrichment analysis revealed that genes with a role in DNA repair and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway were over-represented in a microarray analysis. In a second sub-chronic study, male LMB were fed 3 mg dieldrin/kg feed for approximately 2 months to achieve an environmentally relevant exposure to dieldrin during mid to late stages of sexual maturation. Gene expression profiling identified genes involved in the biological processes of nucleotide base excision, protein transport, and metabolism as being significantly altered by dieldrin, suggesting protein degradation pathways and DNA repair mechanisms were impacted at the genomic level (Martyniuk et al., 2010b). Proteomics analysis in the hypothalamus also revealed that proteins differentially affected by dieldrin included well characterized biomarkers for human neurodegenerative diseases such as apolipoprotein E (ApoE), microtubule associated tau protein (Mapt), and enolase alpha (Eno1). Thus, the molecular and cellular responses identified in these studies may serve as bio-indicators of adverse effects in the brain due to pesticide exposures.

The major objective of this study was to determine the genomic responses in the female and male hypothalamus to the neuroactive pesticide dieldrin. LMB for this study were in early stages of gonad development (August–October). The aforementioned studies by Martyniuk et al. (2010a,b) focused on reproductive animals (February–April) and it is not known if LMB in earlier stages of gonad development show differences in transcriptomic responses to dieldrin. Studies on non-reproductive (i.e. sexually regressed) adults are important because gene expression profiles are known to vary naturally throughout the reproductive cycle in the fish hypothalamus (Zhang et al., 2009) and it was hypothesized that dieldrin affects LMB differently based on the time of year and reproductive state. The hypothalamus was chosen because this neuroendocrine tissue regulates pituitary hormone release of the gonadotropins, luteinizing and follicle stimulating hormone (LH and FSH). The hypothalamus of teleost fish is also a sensitive target for dieldrin neurotoxicity because of its high concentration of GABAergic cells (Martyniuk et al., 2007a). LMB are semi-synchronous spawners and in Central Florida, LMB are typically pre-vitellogenic in September and October, reaching sexual maturity in early March to late April. LMB in August were used for this study because these animals have significantly less circulating levels of steroids compared to sexually mature LMB (Sabo-Attwood et al., 2004; Doperalski et al., 2011). LMB were fed either control, 3 mg dieldrin/kg feed, or 3 mg dieldrin + 0.7 mg E2/kg feed over 60 days to test the null hypotheses that (1) males and females do not differ in the genomic response in the hypothalamus after sub-chronic dieldrin exposure and (2) dieldrin + E2-fed males do not show a reduced transcriptomic response when compared to dieldrin-fed males. Due to its well known neuroprotective role, it was reasoned that co-treatment with E2 in sexually regressed LMB males would mitigate or reduce the response to dieldrin in male LMB.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Largemouth bass and experimental feeding regime

Largemouth bass were purchased from the American Sport Fish Hatchery (Montgomery, Alabama) in July 2009 and maintained at the Aquatic Toxicology Laboratory at the Center for Environmental and Human Toxicology (University of Florida). Average weight (±SD) of the LMB was 558 (±103.6) g and the tail length was 33.1 (±1.82) cm. The age of the LMB was approximately 2–3 years. LMB were acclimated in aerated 160-gallon fiberglass tanks for three weeks before the exposures. The tanks are a flow through system. One month before initiating the feeding study, LMB were treated with a regime of oxytetracycline, nitrofurozine, and Rid-ick for the treatment of parasites and infection.

Dieldrin was incorporated into the feed pellets at a concentration approximating 3 mg dieldrin/kg feed. This dose was chosen based on previous data that demonstrated that treatment with 3 mg dieldrin/kg feed resulted in a whole carcass dieldrin body burden that approximated body burdens of animals placed into mesocosms in the North Shore of Lake Apopka, Florida (Denslow, unpublished data). This region is heavily contaminated with OCPs and other legacy pesticides. Therefore, the experimental dose results in body burdens that are environmentally relevant for wild LMB inhabiting contaminated areas in Florida.

For diet preparation, dieldrin was dissolved in 90% ethanol, mixed with menhaden oil (5% w/w), and coated onto a trout diet (Silver Cup, Odgen Utah) using a cement mixer. Pellets were allowed to air dry and it was assumed that the EtOH was largely evaporated prior to feeding regime although this was not tested. The volume of EtOH was negligible compared to fish oil used for the pellets and it was less than 0.1% of the total volume. This was repeated for the dieldrin + E2 diet, except that this diet also contained 0.7 mg E2/kg feed. This dose was based upon data collected previously from LMB inhabiting Lake Apopka (Denslow, unpubl.). We performed a back-calculation that considered the average weight of LMB, the bioaccumulation of E2 in tissue, and the half-life of E2 to reach an estimated dose that would result in an environmentally realistic body burden of xenoestrogen. Space limitations in the aquatic facility did not facilitate an E2-only control. We point out that E2 was only used to probe the hypothesis that E2 mitigates the transcriptomics response to dieldrin. Thus, we are unable to comment on which responses in the hypothalamus were directly due to estrogen. Control pellets were prepared by adding 90% ethanol mixed into menhaden oil. Sexually immature male and female LMB were fed experimental diets ad lib. (~1% BW/day) beginning August 17 (2009). Natural photoperiod was maintained throughout the experiment. Average temperature throughout the experiment was 27.2 °C (ranged 25–28 °C) and the average dissolved oxygen content was 6.1 mg/L (ranged 4.8–6.5 mg/L).

There were a total of 12 tanks that housed both male and female LMB (7–8 fish/tank) for the duration of the experiment. Sex of the LMB could not be determined beforehand. There were four tanks that received control pellets, four tanks that received pellets containing dieldrin, and four tanks that received pellets containing dieldrin + E2. The experiment was terminated October 15, 2009 after 60 days. At the end of the experiment, the fish were anesthetized with sodium bicarbonate buffered MS-222, blood was collected from the caudal vein with a heparinized syringe, and then fish were euthanized by spinal dislocation. Hypothalami were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Fish were visually scored for reproductive stage at the time of dissection. As expected for this time of year in Florida, the majority of LMB had undeveloped gonads that contained follicles in primary growth phases of maturation. When possible, gonadosomatic index (GSI) was recorded for LMB. All animals throughout the experiment were treated as per the guidelines outlined by University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Dieldrin body burden and feed measurements

Determination of dieldrin burden in feed pellets and in LMB muscle was performed as previously described (Martyniuk et al., 2010b), with slight modification. Briefly, 100 μL of internal standard solution (OCP surrogate) containing 9 ppm Ring-13C12-4,4′-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (13C12-DDE; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Andover, MA) in cyclohexane (HPLC grade, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA) was added to approximately 2.5 g of pulverized feed samples followed by extraction with n-hexanes (ACS grade, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc). Clean-up of the primary extract was accomplished by substitution with acetonitrile (HPLC grade, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc) followed by solid-phase extraction chromatography (Gelsleichter et al., 2005). Final chromatography eluant was evaporated under nitrogen at 37 °C until solvent-free and reconstituted in 100 μL of cyclohexane.

LMB muscle (2.5–3 g) was frozen in liquid nitrogen, pulverized (BioSpec BioPulverizer, BioSpec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK), and transferred to a Teflon-capped glass extraction vial. One hundred microliters of internal standard solution containing 4.5 ppm 13C12-DDE in cyclohexane was added to each sample vial followed by vortex mixing. The DDE surrogate was used to normalize all OCP values. Primary organic extraction of muscle samples was performed by the method of Gelsleichter and colleagues (2005) and repeated twice.

Clean-up of muscle extracts was accomplished by gel permeation chromatography based on the method of Takazawa et al. (2008). A glass chromatography column (25 mm inner diameter, effective length of 450 mm, Chemglass Life Sciences, Vineland, NJ) was packed with 50 g of Bio-Beads SX-3 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA), pre-swollen in 1:1 (v/v) of dichloromethane/ cyclohexane (HPLC grade, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc; herein referred to as column mobile phase). Each primary muscle extract volume was reduced on a rotary evaporator (Büchi Rotavapor R110, Büchi Corp., New Castle, DE), transferred to a glass scintillation vial, evaporated until solvent-free under nitrogen at 37 °C, and reconstituted in 2 mL of column mobile phase. The reconstituted extract was applied to the column bed along with a 1 mL wash of the scintillation vial. Each sample was eluted with 275 mL of column mobile phase using ~15 psi back pressure, and the organochlorine compounds were collected in the fraction between 150 and 275 mL. The collected fraction was evaporated until solvent-free and reconstituted in 100 μL cyclohexane.

Analysis of dieldrin concentration by GC-MS was performed as recently described (Martyniuk et al., 2010b) by comparing sample measurements to a standard curve containing increasing concentrations of dieldrin along with 4.5 or 9 ppm of the internal standard 13C12-DDE, in cyclohexane. GC separation was accomplished using a 5% phenylmethylpolysiloxane fused silica column with helium as carrier gas (HP-5MS, 30 m × 250 μm inner diameter, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Selective ion monitoring was utilized to record ion spectra during set retention windows. Primary and qualifier mass to charge ratios used, respectively, were 262.9 and 260.0 for dieldrin and 258.1 and 330.0 for 13C12-DDE. Standard and sample values were determined by calculating the ratio of the integrated peak area of dieldrin/13C12-DDE. Data are expressed as mass of dieldrin per wet weight of tissue or feed, respectively. The limit of detection in the 100 μL reconstituted sample extract (prior to normalization to extracted sample weight) was ~50 μg/L for both muscle and feed samples. Dieldrin detected in muscle extract (prior to tissue normalization) was 3.3- to 20-fold higher than the limit of detection of the method. The R2 value of the standard curve was 1.0 using linear regression.

2.3. Plasma vitellogenin and E2

LMB vitellogenin (Vtg) standard was purified by anion exchange chromatography as described previously in Denslow et al. (1999). Briefly, concentrations of plasma Vtg in LMB treated with dieldrin and E2 were determined by direct Enzyme-Link Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) using the monoclonal antibody, 3G2 (HL1393). Plasma samples were diluted 1:100, 1:10,000, and 1:100,000 with 10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% azide, 10 KIU/mL Aprotinin, pH 7.6 (PBSZ-AP). LMB Vtg standards (12 point dilution series from 0 to 1.0 μg/mL) were prepared in male plasma at the same dilution as the samples. The secondary antibody used was goat anti mouse IgG-biotin (Pierce), which was added to each well at 1:1000 dilution in 1% BSA/TBSTZ-AP and incubated at room temperature for 2 hr. The plates were developed with a strepavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Pierce) at 1:1000 dilution in 1% BSA/TBSTZ-AP and 1 mg/mL p-nitro-phenyl phosphate in carbonate buffer (30 mM carbonate, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 9.6). Reactions were measured at 405 nm on an ELISA plate reader (SpectraMax Plus384, Applied Biosystems) and VTG concentrations were determined using the SoftMax Pro analysis program. The limit of detection for the LMB Vtg ELISA was 0.001 mg/mL. All assays were performed in triplicate and reported as the mean of the three measurements. The coefficient of variation was <10% for all samples analyzed. Inter and intra-assay variability was measured by analyzing positive controls on several plates and different assays, and was found to be <10%, and <5%, respectively.

LMB circulating E2 levels were determined as previously described (Doperalski et al., 2011), and is summarized briefly here. 100 μL of each plasma sample was combined with 30 μL of tritiated-E2 (50 nCi/mL, specific activity of 44 Ci/mmol; Amersham Radiochemicals, now GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) and extracted by liquid–liquid technique using 1-chlorobutane (n-butylchloride, >99% pure, Acros Organics/Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Extracts were evaporated until solvent-free and reconstituted in 130 μL BSA buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.1% gelatin, 0.1% RIA grade bovine serum albumin, pH 7.6) overnight at 4 °C on an orbital shaker. A subset of samples was reprocessed because of low E2 and 300 μL of plasma sample was used and reconstituted in 300 μL. E2 concentration in reconstituted extracts was determined using a commercially-available ELISA kit (IBL America, Minneapolis, MN) along with extracted standards created in charcoal-stripped LMB plasma. Extraction recovery of samples and standards was determined by counting 10 μL of each reconstituted extract and comparing to the original tritiated-E2 spike solution. E2 concentration was corrected for extraction recovery and expressed as pg/mL plasma. The lower and upper limit of quantitation of the ELISA was 25 and 2000 pg/mL, respectively.

2.4. Gene expression analysis using the LMB oligonucleotide 8 × 15 K microarray platform

Gene expression analysis was performed on four individuals for each of the female and male control groups and four individuals for each of the three treatments (n = 20 microarrays). The experiment began when LMB were sexually immature in August (perinuclear stages) and ended in October when LMB typically begin to enter early secondary growth stages (cortical alveoli, early vitellogenesis). Total hypothalamic RNA extraction for microarray analysis has been previously described (Martyniuk et al., 2010a). RNA integrity values (RIN) were >8.3 for all samples used in the microarray and real-time PCR analysis with an average RIN of 8.9 (2100 Bioanalyzer, Agilent).

Microarray hybridizations were performed according to the Agilent One-Color Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis protocol using Cyanine 3 (Cy3) and 1 μg total RNA per sample was used for the production of cDNA and labeled/amplified cRNA as per the Agilent Low RNA Input Fluorescent Amplification Kit. Labeling methodology followed as previously described in LMB (Martyniuk et al., 2010a). Each LMB hypothalamus sample showed a specific activity >9.0 pmol Cy3/μL and amounts were adjusted to a final mass of 600 ng for 8 × 15 K microarray hybridizations. All steps followed the protocol as described by the manufacturer. Microarrays were scanned at 5 μm with the Agilent G2505 B Microarray Scanner. Agilent Feature Extraction Software (v9.5) formed a composite of two full scans and calculated parameters for Extended Dynamic Range. The quality of microarray data was evaluated by manual inspection and each microarray was deemed to be of high quality.

2.5. Microarray analysis

Raw expression data were imported into JMP® Genomics v3.2. Raw intensity data for each microarray was normalized using both Loess normalization (smoothing factor of 0.2) and Quantile normalization. Regression analysis revealed there was high correspondence in relative fold changes between the two statistical approaches (R2 > 0.95, p < 0.001) and in the identification of regulated transcripts (>95%). Quantile normalization was chosen based upon overall performance according to Kernel density plots and box plots for quality control of normalization. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by an FDR post hoc test for multiple comparisons was used to identify differentially expressed gene probes. Control females were compared to dieldrin treated females. Similarly, control males were compared to the two male treatment groups (dieldrin alone and dieldrin + E2). All LMB probes identified as differentially expressed and used for further analyses had an expected value (E-value) of <10 × E−04 and any duplicates were combined for gene set enrichment and sub-network enrichment analysis. Raw microarray data for this experiment have been deposited into the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (series GSE27963; platform GPL13229).

2.6. Expression clustering, functional enrichment analysis, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), and sub-network enrichment analysis (SNEA)

Gene expression data were subjected to hierarchal clustering in JMP Genomics to better visualize global patterns of gene responses. A probe was used in the clustering if it showed a raw p-value < 0.05 in one or more of the treatment groups. Hierarchal clustering involved complete linkage and used normalized expression data (Quantile normalized). Functional enrichment of gene ontology terms and Principle Component Analysis (PCA) was performed in JMP Genomics (V5.1).

Pathway Studio 7.1 (Ariadne, Rockville, MD, USA) and ResNet 7.0 (Mammals) (Nikitin et al., 2003) were utilized for two different bioinformatics; gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and sub-network enrichment analysis (SNEA). These two different approaches were employed to gain additional insight into the dieldrin dataset. GSEA is a method widely used in microarray analysis to determine if molecular signatures are enriched for a specific annotated cell pathways (i.e. cell cycle or glycolysis) (Subramanian et al., 2005). GSEA was used to identify known pathways or gene ontologies significantly impacted by dieldrin. Briefly, in GSEA, genes are united by a shared factor, such as functional classification or pathogenesis. Enrichment scores are generated based upon whether genes are correlated with the experimental treatment and the score represents whether genes in a known pathway are positively or negatively correlated with each other. SNEA analysis differs from GSEA in that sub-networks are built based upon the relationship of the regulated gene with other genes or proteins in the same biological pathway. Entities are “connected” to each other based upon relationships that are user defined (i.e. binding partners, expression targets, protein modification targets, cell process). An algorithm compares the sub-network distribution of the regulated genes to the background distribution of other genes in the characterized interaction network. Thus, data mining of the ResNet 7.0 database yields interactions among molecular and cell processes. SNEA was used to determine whether there were any interaction sub-networks affected by dieldrin. SNEA has been used successfully for studying mammalian diseases (Kotelnikova et al., 2012) and fish toxicology (Martyniuk et al., 2012).

A total number of 3887 genes were successfully mapped to human homologs using the Entrez GeneID. Only LMB genes that showed high homology to well characterized human genes (NR < 10−4) were used in the analysis. In order to utilize the vast amount of information from the ResNet database (over 1 million abstracts and manuscripts of molecular interactions), human homologs must be used. It is acknowledged that molecular interactions in fish may deviate from mammalian responses, however for the purposes of this study responses are assumed to be conserved in vertebrates. For GSEA, genes were permutated 400 times using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov classic approach as an enrichment algorithm. To broaden the analysis, all pathways were expanded to include cell processes and functional classes in target gene seeds. Enrichment p-value cut-off was set at p < 0.05. Gene set categories examined for enrichment within the microarray data included the curated Ariadne cell signaling and metabolic pathways and gene ontology categories. Sub-Network Enrichment Analysis (SNEA) was also performed to determine if there were specific gene sub-networks affected by dieldrin. These networks included those that are based on common regulators of expression and common protein binding partners. The enrichment p-value for gene seeds was set at p < 0.05.

2.7. Real-time SYBR green PCR assay for ER isoforms

The ERs (esr1, esr2b, and esr2a) were chosen for further investigation with real-time PCR because of evidence that dieldrin affects expression of esr transcripts in the hypothalamus of sexually mature LMB (Martyniuk et al., 2010a,b). ER isoforms were also identified by microarrays as differentially expressed before FDR correction by dieldrin in all three treatment groups. Primers with optimal annealing temperature ~60 °C were designed to amplify sequences of 70–100 base pairs (bp) (Table 1). PCR cycling conditions follow that of Martyniuk et al. (2009). Standard curves for the ER isoforms have been previously optimized and ER isoform specificity has been confirmed (Sabo-Attwood et al., 2004). Standard curves relating initial template copy number to fluorescence and amplification cycle were generated using pGEM-®T easy vector containing the gene target as a template. Linearity and efficiency of standard curves were the following: esr1 (efficiency = 89%, R2 = 0.996), esr2b (efficiency = 91.7%, R2 = 0.998), esr2a (efficiency = 100.8%, R2 = 0.998) and ribosomal 18S (efficiency = 90%, R2 = 0.988). Absolute copy number of estrogen receptors was divided by absolute copy number of ribosomal 18S to yield normalized copy number in each individual.

Table 1.

LMB primers used in the study for real-time PCR. The real time PCR (qPCR) ER primers have previously been shown to be specific to each ER subtype (Sabo-Attwood et al., 2004). Note that the forward primer is provided as 5′ to 3′ orientation in relation to the 5′ to 3′ coding strand (sense) deposited in GenBank and the reverse primer is 5′ to 3′ in relation to the complementary strand (anti-sense).

| Gene | Forward primer (5′ –3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| esr1 | CGA CGT GCT GGA ACC AAT GAC AGA G | TCC GGT CAC TGA TGA TTT TCC TCC T CCA | 132 |

| esr2b | CCG ACA CCG CCG TGG TGG ACT C | AGC GGG GCA AGG GGA GCC TCA A | 117 |

| esr2a | GTG ACC CGT CTG TCC ACA CA | TCT GGG GTC AGT GCA GGA GA | 104 |

| ribosomal 18S | CGG CTA CCA CAT CCA AGG AA | CCT GTA TTG TTA TTT TTC GTC ACT ACC T | 86 |

Transcript levels of esr1, esr2a, and esr2b were measured in the hypothalamus using real-time PCR (MyiQ2 Two-Color Real-Time PCR Detection System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Details of real-time PCR assay have been previously described in Martyniuk et al. (2010a,b). Each gene analysis included (1) two samples that did not receive reverse transcriptase (no RT control) and (2) two samples that did not receive the cDNA template (no NTC). All RIN values were above >8.3 for samples used in real-time PCR (2100 Bioanalyzer, Agilent). Melt curves for each gene indicated a single product being formed.

2.8. Statistics

All data were tested for the assumption of normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness of fit test and homogeneity of variance was tested using Levene’s test. Data not meeting assumption for normality were log 10 transformed. Transformed data not meeting assumptions were evaluated using a non-parametric Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis Test when appropriate. All analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics v17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Dieldrin and E2 in feed and muscle of male and female LMB

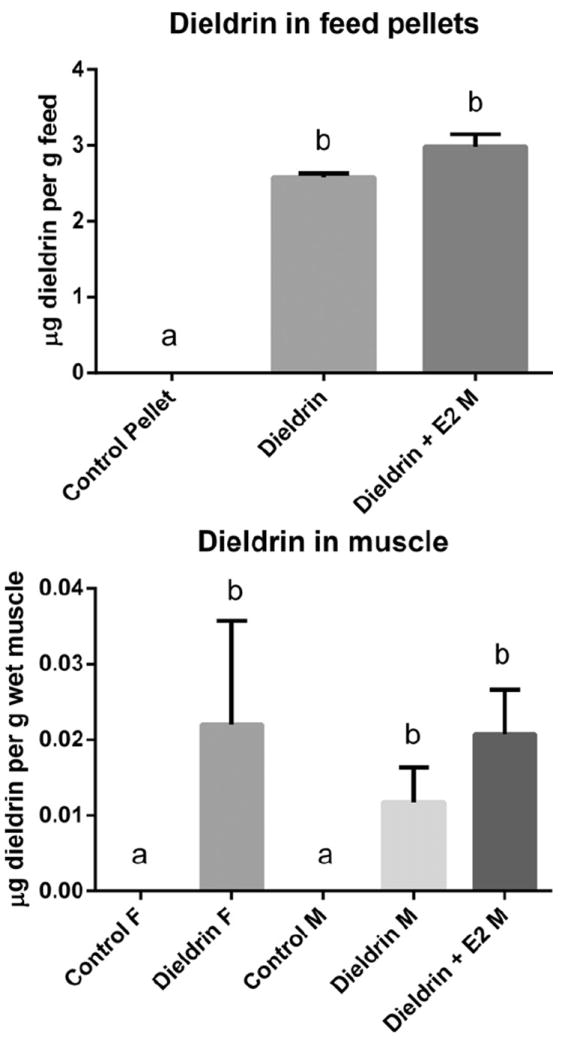

The feed analysis indicated that both treatment pellets contained 2.58 ± 0.04 ppm (μg dieldrin per g feed) and 2.98 ± 0.12 (μg dieldrin per g feed) while the control pellets did not contain any detectable levels of dieldrin (Fig. 1). For the group receiving dieldrin and E2, the E2 in feed was measured at 43.93 PPB and 45.95 PPB. There was no detectable E2 in control feed or feed with dieldrin alone.

Fig. 1.

Dieldrin in control and experimental feeds (dieldrin alone and dieldrin + E2) (upper graph) and concentration of dieldrin in muscle samples after 2 month feeding regime (lower graph). Dieldrin was undetectable in muscle tissue from control animals.

After treatment, it was determined that dieldrin levels in female and male LMB muscle (n = 4/treatment) did not significantly differ in treatment groups (Fig. 1) and ranged between 0.06–0.038 μg dieldrin per g wet muscle. There were no detectable traces of dieldrin in control muscle (3 female and 3 male, n = 6) (Fig. 1). E2 was not measured in the muscle tissues of LMB.

3.2. Reproductive endpoints of GSI, Vtg, and Plasma E2

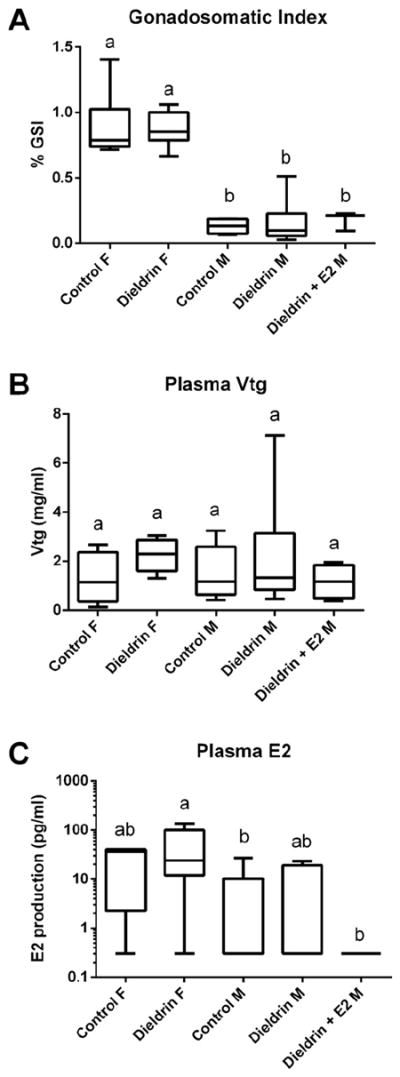

GSI for female controls and males treated with both dieldrin + E2 were determined not to be normally distributed and could not be transformed to approximate normality. Therefore, a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis Test was used to test for differences among groups. Females had a significantly higher GSI than males (p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in GSI in either male or female LMB after treatments (Fig. 2A). GSI ranged from 0.66% to 1.4% for the females and <0.1% (could not be accurately measured) to 0.5% for the males. Approximately 30% of the males had little gonad development (testes were ribbons and GSI < 0.1) indicating that these animals were in early primary growth stages. Mean (±SEM) GSI for female control was 0.90% (±0.08%), dieldrin fed females was 0.87% (±0.05%), male control was 0.13% (±0.03%), dieldrin fed males was 0.16% (±0.05%), and dieldrin + E2 fed males was 0.18% (±0.04%).

Fig. 2.

(A) Gonadosomatic index of control and treated female and male LMB (control females, n = 10; dieldrin-treated females, n = 7; control males, n = 4; dieldrin-treated males, n = 10; dieldrin + E2 treated males, n = 4). There were animals in each group in which GSI could not be calculated because the gonad was too small to quantify accurately. (B) Plasma vitellogenin in female and male LMB (control females, n = 8; dieldrin-treated females, n = 6; control males, n = 9; dieldrin-treated males, n = 10; dieldrin + E2 treated males, n = 4). (C) Plasma levels of 17β-estradiol (E2) (log 10 scale) in female and male LMB (control females, n = 5; dieldrin-treated females, n = 6; control males, n = 8; dieldrin-treated males, n = 7; dieldrin + E2 treated males, n = 4). Horizontal line in box plots is the median, the boundaries of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles (boundaries of the box) and the minimum and maximum data points are represented by the whiskers. Different letters denote significant differences among groups (p < 0.05).

Vtg plasma levels in both females and males were determined not to be equal in variance or normally distributed and a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis Test was used to test for differences among groups. There were no significant differences in plasma Vtg in either female or male LMB (Fig. 2B). When considering all groups, Vtg ranged from 0.372 mg/mL to 7.12 mg/mL in the males and 0.13 mg/mL to 3.04 mg/mL in the females. Mean (±SEM) plasma Vtg for female control was 1.29 mg/mL (±0.34), dieldrin fed females was 2.24 mg/mL (±0.28), male control was 1.51 mg/mL (±0.34), dieldrin fed males was 2.25 mg/mL (±0.71), and dieldrin + E2 fed males was 1.16 mg/mL (±0.35).

E2 plasma levels in both females and males were determined not to be equal in variance or normally distributed and a Kruskal–Wallis Test was used to test for differences among groups. There were significant differences detected across the five groups and a Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine which individual comparisons differed in plasma E2. There were no significant effects of dieldrin on plasma E2 levels in female or in male LMB but E2 in females treated with dieldrin was higher than that of control males and males fed dieldrin + E2 (Fig. 2C) although the sexes differed in the amount of plasma E2. When considering all groups, E2 ranged from not detectable to 26.97 pg/mL in male LMB and from not detectable to 136.11 pg/mL in female LMB. Mean (±SEM) plasma E2 in female control was 24.24 pg/mL (±9.0), in dieldrin fed females was 48.13 pg/mL (±21.49), in male control was 5.39 pg/mL (±3.44), in dieldrin fed males was 6.67 pg/mL (±3.80), and in dieldrin + E2 fed males was undetectable. For statistical analyses, the lowest detectable value for E2 (0.30 pg/mL) based on the standard curve was assigned to individuals that had plasma E2 levels below detection limits of the assay.

3.3. Microarray analysis in the hypothalamus

The total number of probes showing differential regulation in each group at a p-value < 0.05 (prior to FDR) was 2673, 1649, and 638 for females (Dld), males (Dld), and males (Dld + E2), respectively. After FDR correction, microarray analysis identified 531 genes (fold change > 1.5) as differentially expressed in female hypothalamus after dieldrin treatment. After FDR correction, there were 7 transcripts and 1 transcript that were differentially regulated in the male hypothalamus treated with dieldrin and dieldrin + E2, respectively (fold change > 1.5). Cluster analysis, Venn diagrams, and functional enrichment analysis considered non-FDR corrected transcripts (p < 0.05) as significantly changing genes to obtain a less restricted analysis of the transcriptome.

Female LMB had significantly more gene transcripts impacted than either male treatment. A Venn diagram (software developed by Oliveros, 2007) revealed that there were 50 genes in common between the three groups (Supplemental Figure S1). Based on the Venn diagram, the males treated with dieldrin + E2 shared more regulated genes in common with males treated with dieldrin than with the female group. This is further depicted in Supplemental Figure S2, which contains all regulated gene probes organized from decreasing to increasing fold change for each of the three groups. Genes for the males fed dieldrin were organized first, and the other two graphs were generated by keeping the same order of genes as for the males fed dieldrin. Noteworthy is that the male groups share many genes in common than with females (ends of graph) but there are also a subset of genes in the males fed dieldrin and E2 that show expression patterns more similar to females (towards middle of the graph). There are also a significant number of genes that show unique expression in the males fed dieldrin and E2 (middle portion of graph).

Further investigation of transcript changes using regression analysis in female and male LMB fed dieldrin revealed that the mRNA steady state fold changes of the 561 genes that were in common between males and females fed dieldrin was significantly and highly correlated (R2 = 0.82, F = 3283, p < 0.0001), suggesting that this subset of hypothalamic transcripts are affected by dieldrin in the same way in the two sexes. Supplemental Figure S2 also demonstrates this point when comparing the overall gene expression patterns between the females (bottom graph) and males (top graph); the directional changes of overlapping genes at the ends of the graphs are highly similar (however a few genes show the opposite directional change). All LMB gene expression data are provided in Appendix 1.

3.4. Expression clustering and functional enrichment analysis

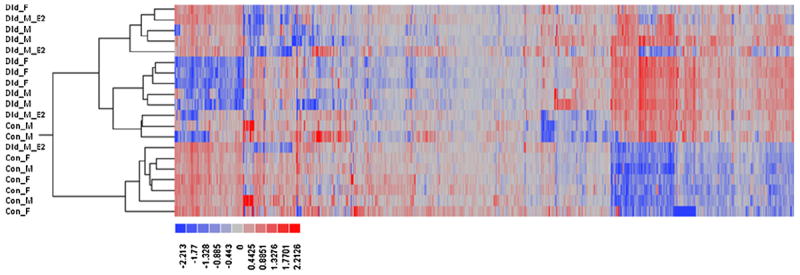

Hierarchal clustering of expression data was conducted on gene transcripts to characterize global patterns of expression (Fig. 3). Overall, the control females and males formed a separate cluster from dieldrin-fed LMB. The dieldrin fed LMB did not form distinct clusters based on sex and were largely intermixed. Principle Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted in JMP Genomics (V5.1) and variation in gene expression was explained by three principle components (Supplemental Figure S3). The PCA revealed that both the control females (red elliptical) and control males (green elliptical) had significant variation in gene expression while the dieldrin treated LMB showed less variation in transcriptomics responses across individuals.

Fig. 3.

Heat map for control and dieldrin-treated LMB using hierarchical clustering. Each row (i.e. gene probe) was first centered to a mean of zero (0) across microarrays prior to analysis, followed by further scaling of the rows to a variance of one (1) prior to clustering. Red intensity means an increase in relative expression while blue means a decrease in relative expression.

Functional enrichment analysis provided novel insight into the cell processes affected by dieldrin in each treatment group (Supplementary Table S1). Some examples of biological processes affected in the dieldrin treated LMB included immune response, ubiquitin cycle, cell redox homeostasis, and G-protein coupled receptor protein signaling pathway while molecular functions included steroid hormone receptor activity, transcription regulator activity, microtubule motor activity, ubiquitin thiolesterase activity, calcium ion binding, and hormone activity.

3.5. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and sub network enrichment analysis (SNEA)

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) identified a number of cell pathways increased or decreased by dieldrin based on gene expression patterns of members in the pathway (Supplementary Table S2). Most notable was that there was a varied response in pathways across all three treatments. A cell process was considered to be differentially affected by treatment if the median fold change was greater than 10% for the entire pathway in the GSEA. In the female hypothalamus, dieldrin increased gene levels of those involved in the signaling of dopamine receptor 2, vasopressin receptor 1, tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR), and nerve growth factor receptor signaling. In males, dieldrin decreased the pathways involving apoptosis regulation and receptor mediated signaling for follicle stimulating hormone, B-cells, angiopoietin, growth hormone, and interleukin 7. In males fed dieldrin and E2, few pathways were altered using GSEA; the only three altered were growth hormone signaling, serotonin receptor signaling, and the protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, C signaling cascade.

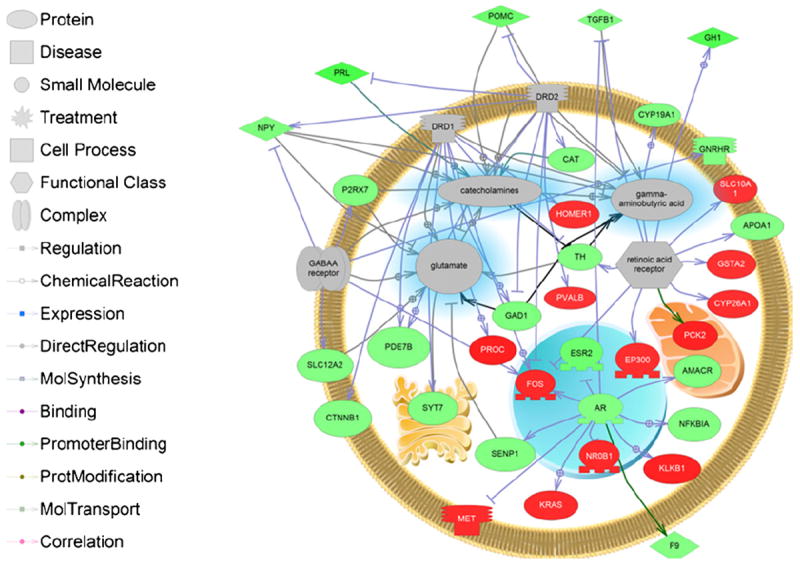

Sub network enrichment analysis (SNEA) analysis also suggested that there were unique gene seed targets regulated in each sex. Prevalent themes emerged in the SNEA expression target analysis that included neuropeptide receptor signaling, steroid signaling, and transcription factor families, and regulation of transcription (Table 2, Appendix 2). Interestingly, most of the gene networks were decreased overall in the hypothalamus across all three treatment groups. Many gene set seeds were involved in neurotransmitter and neurohormone expression targets. In the female hypothalamus, dieldrin affected expression targets of GnRH, retinoic acid receptor, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, and dopamine receptor D1 signaling whereas dieldrin affected GnRH, nuclear receptor coactivator 2, androgen receptor, follistatin, GABAA receptor, and dopamine receptor D2 signaling in males fed dieldrin only. Fig. 4 depicts an expression network for DA and GABA receptor signaling (DRD1, DRD2, and GABAA) and their association with neurotransmitter production (indicated with a blue hue). Also included in the network are retinoic acid signaling and AR signaling. All of these expression networks were significantly affected in males or females but not males fed E2 (Table 2). The figure demonstrates that dieldrin can potentially impact glutamate, catecholamine, and GABA signaling in the CNS through the identified receptor mediated cascades.

Table 2.

Sub network enrichment analysis (SNEA) for neuroendocrine signaling and hormone receptor expression targets in the LMB hypothalamus (p <0.05). Gene set seeds listed are those that had greater than 10% change in expression targets. The complete list of sub-networks is found in Appendix 2. Neighbors refer to entities in which the expression is regulated by the gene set seed while total number of neighbors is known entities in the specific network.

| Exposure group | Gene set seed | Total # of neighbors | # of measured neighbors | Median change | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| female Dld | Retinoic acid receptor | 52 | 11 | −1.294 | 0.022 |

| female Dld | Thyrotropin-releasing hormone | 25 | 8 | −1.256 | 0.010 |

| female Dld | Activin | 89 | 20 | −1.124 | 0.049 |

| female Dld | Retinoid-X receptor | 183 | 43 | −1.104 | 0.039 |

| female Dld | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone 1 | 109 | 27 | −1.101 | 0.016 |

| female Dld | Follicle stimulating hormone | 74 | 20 | 1.115 | 0.045 |

| female Dld | Dopamine receptor D1 | 20 | 8 | 1.220 | 0.008 |

| male Dld + E2 | Thyrotropin-releasing hormone | 25 | 8 | −11.919 | 0.004 |

| male Dld + E2 | Peptide hormone | 10 | 6 | −11.919 | 0.044 |

| male Dld + E2 | Orphan nuclear hormone receptor | 25 | 7 | −1.246 | 0.001 |

| male Dld + E2 | Activin | 89 | 20 | −1.138 | 0.002 |

| male Dld + E2 | Vasoactive intestinal peptide | 90 | 12 | −1.138 | 0.028 |

| male Dld + E2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 1 | 53 | 17 | 1.128 | 0.000 |

| male Dld + E2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 2 | 49 | 10 | 1.134 | 0.009 |

| male Dld | Thyrotropin-releasing hormone | 25 | 8 | −8.308 | 0.000 |

| male Dld | Peptide hormone | 10 | 6 | −8.308 | 0.005 |

| male Dld | Nuclear receptor coactivator 2 | 38 | 5 | −1.682 | 0.039 |

| male Dld | Follistatin | 21 | 7 | −1.560 | 0.006 |

| male Dld | GABAA receptor | 11 | 5 | −1.560 | 0.034 |

| male Dld | Dopamine receptor D2 | 27 | 8 | −1.512 | 0.031 |

| male Dld | Galanin | 13 | 6 | −1.397 | 0.041 |

| male Dld | Activin | 89 | 20 | −1.391 | 0.005 |

| male Dld | Steroid hormone receptor | 27 | 8 | −1.391 | 0.015 |

| male Dld | Insulin | 45 | 5 | −1.365 | 0.034 |

| male Dld | GNRH1 | 109 | 27 | −1.333 | 0.009 |

| male Dld | Androgen receptor | 51 | 11 | −1.317 | 0.011 |

| male Dld | Cholecystokinin | 27 | 9 | −1.238 | 0.030 |

| male Dld | Adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1 | 100 | 26 | −1.235 | 0.050 |

| male Dld | Luteinizing hormone | 51 | 12 | −1.174 | 0.019 |

| male Dld | Gonadotropin | 157 | 34 | −1.174 | 0.026 |

Fig. 4.

Pathway analysis of significantly changing expression sub-networks in LMB hypothalamus. The networks shown in the pathway are dopamine receptors DRD1 and DRD2, GABAA receptor, AR, and retinoic acid receptor expression targets. These signaling networks will have a significant impact on neurotransmitter systems that include GABA, catecholamines, and glutamate. Abbreviations are provided in the abbreviation list.

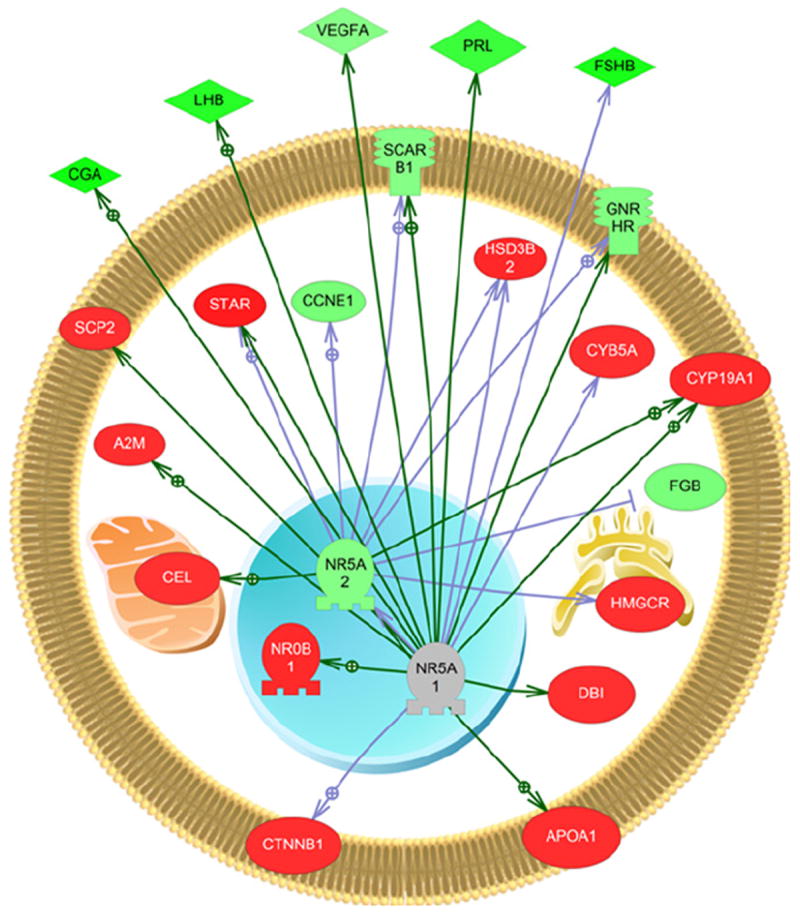

Males fed dieldrin and E2 showed changes in vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 1 (NR5A1), and nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 2 (NR5A2). Interestingly, NR5A1 and NR5A2 are two nuclear receptors that were not affected in females or males fed dieldrin and may underlie a unique signaling pathway in the males fed dieldrin and E2. Fig. 5 explores this gene network in more detail with known regulators of this pathway. Noteworthy is that the majority of gene targets within the cell are increased in mRNA expression while those outside the cell are downregulated.

Fig. 5.

Pathway analysis for the expression network of nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 1 and 2 in males fed dieldrin and E2. This network was unique to this group. The majority of the genes found within the cell are increased in expression. Abbreviations are provided in the abbreviation list. Legend follows that provided in Fig. 4.

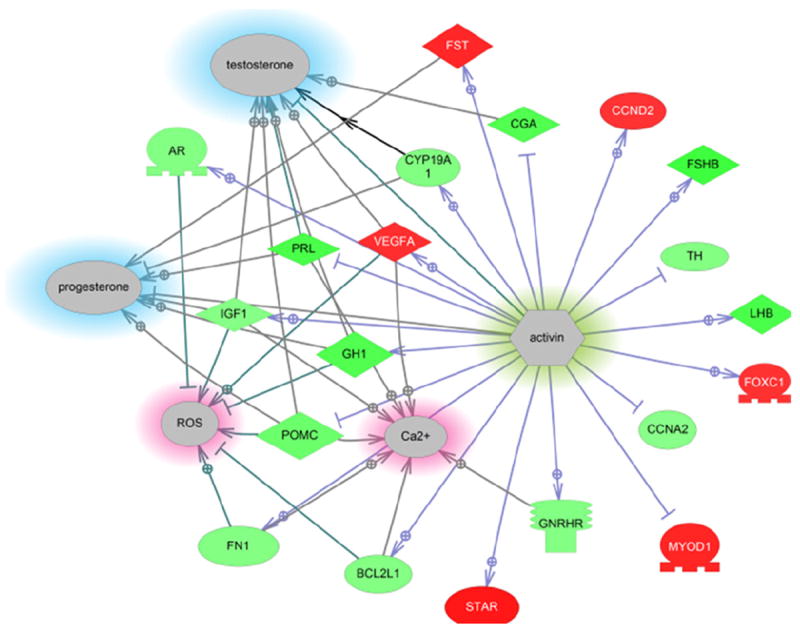

As pointed out, there were few processes that overlapped in the three groups. Interestingly, activin signaling was one expression sub-network that was decreased in all three groups. Fig. 6 shows a representational network for the data collected for males fed dieldrin. Via this network, small molecule signaling that includes Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are affected as well as steroid production (testosterone and progesterone). All the results from the GSEA and SNEA analysis are provided in Appendix 2.

Fig. 6.

Sub-network for activin signaling in the hypothalamus after males were fed dieldrin. However, this network was significantly reduced in all three treatment groups (~20–30%), suggesting it is affected by dieldrin. This network has the potential to also affect steroid production in the neuroendocrine brain and is involved in calcium signaling and response to reactive oxygen species. Abbreviations are provided in the abbreviation list. Legend follows that provided in Fig. 4.

3.6. Real-time PCR of estrogen receptors

Gene expression data were not normally distributed and a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used to determine if there were significant differences (p < 0.05) in steady state mRNA levels between control and treatment. Real-time PCR corresponded to microarray data in that transcripts showed a reduced trend. However, there was no significant change in the steady state mRNA abundance of esr2b and esr2a in LMB (Supplemental Figure S4) using real-time PCR. The variability in control samples was high and this may have precluded us from detecting differences due to dieldrin treatments. In addition, due to the low abundance of esr1 in the hypothalamus in sexually regressed LMB, esr1 could not confidently be evaluated by the real-time PCR assay.

Despite the lack of a significant change using real-time PCR, the microarray analysis suggested that female LMB fed dieldrin exhibited a significant decrease in both esr1 and esr2b mRNA levels (Supplemental Table S3). In addition, the microarray analysis suggested that male LMB fed dieldrin exhibited a significant decrease in esr2b mRNA levels and that male LMB fed dieldrin + E2 experienced a significant decrease in esr2a mRNA levels. Taken together, dieldrin appeared to downregulate ER mRNA levels in the hypothalamus of sexually regressed LMB.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reproductive endpoints

Dieldrin and E2 treatment in this study had no significant impact on GSI, plasma Vtg, or E2 levels. In contrast, Garcia-Reyero et al. (2006) fed dieldrin to LMB (0.4 and 0.81 μg/g) for 120 d during prime reproduction season (December–March) and observed significant changes in plasma E2/11-KT ratios in both females and males. The major differences between this study and that of Garcia-Reyero et al. (2006) are the reproductive stage of the females (primary growth versus late secondary growth), the feed concentration (3 ppm dieldrin versus <1 ppm dieldrin), and the length of the feeding regimes (2 months versus 4 months). We suggest that the lack of change in plasma E2 may be due to a lack of tissue responsiveness to exogenous E2 at early growth stages. A second reason for a lack of an effect of dieldrin on reproductive endpoints is that the two month feeding regime may have been sufficiently long enough to allow for compensatory mechanisms to take place. These hypotheses involving biological responses of sexually immature individuals compared to sexually mature individuals should be further explored.

Another point to highlight is that plasma Vtg in males were comparable to females in this study. We believe that this is due to the co-inhabitation of the sexes in the experimental tanks. Females were in close proximity to males throughout the duration of the study and this could have resulted in a slightly estrogenic environment. However, it is not possible to quantitate how much impact the co-habitation of females had on male E2 and Vtg levels. Moreover, we did not detect any changes in plasma E2 levels in males fed E2 in the pellets. However, this may not be surprising as studies demonstrate that exogenous treatments to E2 and estrogenic pharmaceuticals can reduce steroid production and lower plasma E2 levels in male fish (Salierno and Kane, 2009; Martyniuk et al., 2010c).

4.2. Dieldrin induces sex-specific gene responses in the LMB hypothalamus

In the hypothalamus, there were 561 genes (~20–30%) affected by dieldrin that were in common between the females and males, suggesting that the majority of regulated genes affected by dieldrin were sex-specific. Most striking was that the majority of cell pathways identified by GSEA were significantly increased in females while the majority of cell pathways were significantly decreased in males. In addition, there was little overlap in significantly regulated pathways in females and males despite the females and males having a core group of regulated genes that were affected in a similar way. Taken together, these data in general suggest that the male and female brains are responding differently to the contaminant exposure. This is corroborated by studies in mammals that demonstrate that the female and male brains can differ significantly in gene expression profiles, despite having near identical genomes. In a study investigating 169 female and 165 male mice, there were ~650 transcripts (14%) in the adult brain that showed sexually dimorphic expression (Yang et al., 2006). Identifying sexually dimorphic gene responses in the neuroendocrine brain are particularly important because the brain plays a key role in sexual differentiation during early development and additional studies should evaluate how aquatic pollutants may alter this process in fish.

4.3. Dieldrin affects genes involved in neurotransmitter receptor signaling and neurohormone production in the LMB hypothalamus

Overall, there appears to be significant impacts of dieldrin in GABAergic and dopaminergic signaling in the LMB neuroendocrine brain. GABAA receptor signaling was affected in the male LMB hypothalamus; a gene network that was predicted to be altered based upon the characterized mode of action of dieldrin (i.e. GABAA receptor antagonism) (Gant et al., 1987). SNEA also identified dopamine receptor signaling networks as putative targets of dieldrin in males and females. Dieldrin has been linked to neurodegeneration in the vertebrate CNS (Kanthasamy et al., 2005) and there is evidence that dieldrin can preferentially target dopamine neurons in vertebrates. Fetal mouse mesencephalic cultures treated with dieldrin (0.01 to 100 μM) for 24 or 48 h showed reduced numbers of viable cells as measured through tyrosine hydroxylase staining (TH-in cells) (Sanchez-Ramos et al., 1998). Transcriptional dysregulation of GABA and DA signaling is consistent with the mode of action of dieldrin.

In addition to neurotransmitter signaling, downstream gene targets of neuropeptides were altered by dieldrin and included GnRH, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, vasopressin, follicle stimulating and luteinizing hormone and activin. Many of the neuropeptide expression networks were significantly decreased after treatments to dieldrin. The mRNA steady state abundance of neuropeptides in the vertebrate CNS has previously been shown to be affected by organochlorines. In PC12 cell lines, dieldrin increased mRNA levels from neurohormones that included, corticotropin releasing hormone, neuropeptide Y, and tachykinin 1 (Slotkin and Seidler, 2010) and methoxychlor, another OCP, has been shown to significantly suppress GnRH mRNA levels in GT1-7 cells (Gore, 2002). It has been pointed out that the fish neuroendocrine system is understudied in the context of environmental pollutants. Waye and Trudeau (2011) provide evidence in their critical review that the teleostean neuroendocrine system is a sensitive target for pesticides, industrial waste, personal care products, and pharmaceuticals. The implications for dysregulation of the neuroendocrine system are that pituitary hormone release will be affected at multiple levels and can result in changes in growth, reproductive, stress, and the metabolic axes. Dieldrin can disrupt genes that affect GABA and dopamine signaling, as well as neurohormones expression, and this can have implications for reproduction given the fact that GABA and dopamine have stimulatory and inhibitory roles respectively in the control of luteinizing hormone release (Trudeau et al., 2000). These studies suggest that the neuroendocrine system is a major target for adverse effects by pesticides.

4.4. Males fed dieldrin and E2 show unique responses compared to dieldrin fed LMB

One hypothesis tested in this study was that males fed dieldrin and E2 would show an attenuated or reduced transcriptomics response in the hypothalamus compared to animals fed dieldrin alone. Although there were genes in common between the males that were differentially affected, the males fed dieldrin and E2 showed fewer gene changes and fewer disrupted pathways (based on GSEA) than males fed dieldrin alone. Our PCA analysis also revealed that the transcriptomic pattern in the hypothalamus of males fed both E2 and dieldrin was remarkably similar to the female group fed dieldrin. In addition, in the group of males fed dieldrin and E2, there were 27 genes that responded more like females than males fed dieldrin alone. The reduced numbers of genes and pathways altered by co-treatment, may be evidence for attenuation of the transcriptomics response by E2. It is speculative to suggest that this is related to neuroprotective effects of E2 in the CNS; however studies suggest that E2 can mitigate excessive stimulation of GABAA receptors. Muscimol is a potent GABAA receptor agonist and co-treatment of both muscimol and E2 into neonatal rats resulted in the diminished release of lactate dehydrogenase in primary hippocampal cultures and fewer TUNEL-immunopositive cells, a measure of cell apoptosis, compared to rats treated with muscimol alone (McClean and Nuñez, 2008). In a study in the CNS of ovariectomized rats, bicuculline, a GABAA receptor antagonist, increased oxidative stress as measured by TBARS levels and counteracted any protective effects of E2 in ethanol-withdrawn animals (Rewal et al., 2004). This may be due to reduced localized E2 production by the brain. Evidence for this is provided by studies in rat hippocampal cell cultures, which reported that supplementation of media with bicuculline resulted in decreased E2 production from the cells (Zhou et al., 2007). Dieldrin is also a GABAA receptor antagonist and its downstream cellular actions may also have direct effects on local neuroestrogen production. Regardless of the mechanisms, there is good evidence to suggest that E2 neuroprotection involves interaction with the GABA system and it is plausible that co-treatment with E2 attenuated the transcriptomics response in the LMB hypothalamus. Additional endpoints in the hypothalamus (apoptotic assays) or a behavioral component to this study would better elucidate whether there were protective neurological mechanisms at work.

An up-regulated signaling pathway that was unique to the males fed dieldrin and E2 was constructed from gene set expression targets and included NR5A1nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 1 (NR5A1) and 2 (NR5A2). NR5A1, also known as steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1), is a transcriptional activator involved in sex determination and NR5A2 is an orphan nuclear receptor that binds DNA and activates gene transcription. This network also included genes involved in the steroidogenic pathway such as steroid acute regulatory protein (star) and hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3 beta- and steroid delta-isomerase 2 (hsd3B2). Diazepam binding inhibitor (dbi) and apolipoprotein A1 (apoa1) are also present in this network and are related to steroidogenesis. In addition to stimulating steroidogenic genes such as star, SF-1 has many roles within the CNS and these have recently been reviewed (Büdefeld et al., 2012). In the mammalian CNS, SF-1 expression is restricted to neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus and plays a role in GABA-mediated neuronal migration within the tissue in early development based on evidence that SF-1 knockout mice show disorganized localization of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). Other roles for SF-1 include regulation of feeding and sexual differentiation. In the protandrous black porgy, Acanthopagrus schlegeli, NR5A2 has been shown to be positively correlated in expression, along with androgen and estrogen receptors, during sexual differentiation of the brain (Tomy et al., 2009). Of interest in the current study is that when small molecules were overlaid onto the gene pathway, the NR5A1 and NR5A2 expression network in dieldrin + E2 fed males also included testosterone and progesterone. This suggests that there may also be effects on steroid balance in the hypothalamus by this network. However, whether this is related to GABAergic inhibition by dieldrin or the involvement of E2 in the feed is not clear.

A final point to make is that dieldrin itself has multiple modes of action other than that of GABAA receptor antagonism. One suggested mode of action of dieldrin is to act as a weak estrogen mediating genomic effects through ERs. Dieldrin coupled to the presence of E2 in the feed may have resulted in an estrogenic environment, although it is noted that plasma E2 levels did not dramatically change within dieldrin + E2 fed males. The microarray analysis suggests that esr2b is a transcript that is significantly decreased by dieldrin in the LMB hypothalamus. Modulation of esr2b mRNA steady state levels in the LMB hypothalamus by dieldrin has also been observed in two additional independent experiments with dieldrin (Martyniuk et al., 2010a,b). Therefore, evidence for dieldrin-mediated changes in ER isoform expression within the hypothalamus appears to be consistent in independent studies.

4.5. Activin signaling a target of dieldrin?

One cell signaling pathway that showed a reduction in all three treatment groups was the activin pathway. Females and males fed dieldrin + E2 showed a 12–13% decrease while males fed dieldrin showed a 40% decrease in the activin gene network. This suggests that dieldrin may act to inhibit the pathway regardless of the sex of the animal. Activins are members of the TGF-beta family member and have many roles in cell differentiation, growth, reproduction hormone regulation, and cell survival. Activins are regulated by neurotransmitters in the teleostean neuroendocrine brain (Popesku et al., 2008) and there appears to be a close association between activins and GABAergic synaptic transmission. In the goldfish, activin βa mRNA has been shown to be regulated by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (10 microg/g body weight) (Martyniuk et al., 2007b) but not by the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol. The expression levels of activin βa were increased in both the hypothalamus and telencephalon approximately 3-fold and corresponded to increased LH release by baclofen. Dieldrin exerts its effects through GABAA receptor binding. Antagonism of the GABA receptors may reduce the activin signaling pathway, as evidenced here, and stimulation of GABA receptors through agonists may stimulate activin signaling, however this hypothesis must be tested further. We also observed changes in an activin expression network that is related to Ca2+ regulation and steroids, specifically testosterone and progesterone. One mechanism of E2 neuroprotection may be to attenuate calcium currents through activin signaling. Zheng et al. (2009) show support for interactions between GABA and activin in the context of anxiolytic behaviors in mice, suggesting that activin plays a role in regulating GABAergic pathways. It is therefore hypothesized that the activin pathway is a dieldrin-sensitive expression network that is regulated in part by GABAA receptors.

4.6. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that there is a sexually dimorphic response to dieldrin in the hypothalamus of non-reproductive LMB. Many human neurodegenerative diseases for example, have a significant gender-bias for early onset and disease manifestation (Simunovic et al., 2010). This is specifically of interest here given the fact that dieldrin levels in human plasma have been correlated to increased risk to Parkinson’s disease (Weisskopf et al., 2010). Protective effects of E2 or regulation of steroidogenic-factor-1 expression networks may also explain in part why there are sex differences in some human neurodegenerative diseases and earlier onset in males (Czlonkowska et al., 2005). Sex differences in molecular signaling cascades identified in this study, for example neurotransmitter systems and the immune response may also underlie increased susceptibility to neurological diseases in males.

Lastly, there can be marked differences in transcriptome expression in fish tissues that are dependent upon time of year and reproductive stage. These factors can also be an important determinant of genomic responses in the brain. The teleost neuroendocrine brain transcriptome has been shown to vary at different times of the year (Zhang et al., 2009). Therefore, females and males are expected to exhibit varied responses to aquatic contaminants because of inherent differences in brain physiology and this is an important consideration when measuring molecular responses in the sexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marianne Kozuch of the Analytical Toxicology Core Laboratory at the University of Florida for assistance with dieldrin feed and muscle analysis.

Funding

This research was funded by a National Institutes of Health Pathway to Independence Award granted to C.J.M. (K99 ES016767-01A1) and by the Superfund Basic Research Program from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to N.D. and D.B. (RO1 ES015449).

Abbreviations

- A2M

alpha-2-macroglobulin

- AMACR

alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase

- APOA1

apolipoprotein A-I

- AR

androgen receptor

- BCL2L1

BCL2-like 1

- CAT

catalase

- CCNA2

cyclin A2

- CCND2

cyclin D2

- CCNE1

cyclin E1

- CEL

carboxyl ester lipase (bile salt-stimulated lipase)

- CGA

glycoprotein hormones, alpha polypeptide

- CTNNB1

catenin (cadherin-associated protein), beta 1, 88 kDa

- CYB5A

cytochrome b5 type A (microsomal)

- CYP19A1

cytochrome P450, family 19, subfamily A, polypeptide 1

- CYP26A1

cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily A, polypeptide 1

- DBI

diazepam binding inhibitor (GABA receptor modulator, acyl-Coenzyme A binding protein)

- DRD1

dopamine receptor D1

- DRD2

dopamine receptor D2

- EP300

E1A binding protein p300

- ESR2

estrogen receptor 2 (ER beta)

- F9

coagulation factor IX

- FGB

fibrinogen beta chain

- FN1

fibronectin 1

- FOS

v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- FOXC1

forkhead box C1

- FSHB

follicle stimulating hormone, beta polypeptide

- FST

follistatin

- GH1

growth hormone 1

- GNRHR

gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor

- GSTA2

glutathione S-transferase alpha 2

- HMGCR

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A reductase

- HOMER1

homer homolog 1 (Drosophila)

- HSD3B2

hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3 beta- and steroid delta-isomerase 2

- IGF1

insulin-like growth factor 1 (somatomedin C)

- KLKB1

kallikrein B, plasma (Fletcher factor) 1

- KRAS

v-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- LHB

luteinizing hormone beta polypeptide

- MET

met proto-oncogene (hepatocyte growth factor receptor)

- MYOD1

myogenic differentiation 1

- NFKBIA

nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- NR5A1

nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 1

- NR5A2

nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 2

- NR0B1

nuclear receptor subfamily 0, group B, member 1

- P2RX7

purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel, 7

- PCK2

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 (mitochondrial)

- PDE7B

phosphodiesterase 7B

- POMC

proopiomelanocortin

- PRL

prolactin

- PROC

protein C (inactivator of coagulation factors Va and VIIIa)

- PVALB

parvalbumin

- SCARB1

scavenger receptor class B, member 1

- SCP2

sterol carrier protein 2

- SENP1

SUMO1/sentrin specific peptidase 1

- SLC10A1

solute carrier family 10 (sodium/bile acid cotransporter family), member 1

- SLC12A2

solute carrier family 12 (sodium/potassium/chloride transporters), member 2

- STAR

steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- SYT7

synaptotagmin VII

- TGFB1

transforming growth factor, beta 1

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- VEGFA

vascular endothelial growth factor A

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2012.09.012.

References

- Berchtold NC, Cribbs DH, Coleman PD, Rogers J, Head E, Kim R, et al. Gene expression changes in the course of normal brain aging are sexually dimorphic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15605–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806883105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blocksom KA, Walters DM, Jicha TM, Lazorchak JM, Angradi TR, Bolgrien DW. Persistent organic pollutants in fish tissue in the mid-continental great rivers of the United States. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408:1180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büdefeld T, Tobet SA, Majdic G. Steroidogenic factor 1 and the central nervous system. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24:225–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KP, Mazure CM, Staley JK. Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function, and chemistry. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:847–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czlonkowska A, Ciesielska A, Gromadzka G, Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I. Estrogen and cytokines production – the possible cause of gender differences in neurological diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1017–30. doi: 10.2174/1381612053381693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denslow ND, Chow M, Kroll KJ, Green L. Vitellogenin as a biomarker of exposure to estrogen or estrogen mimics. Ecotoxicology. 1999;8:385–98. [Google Scholar]

- Doperalski NJ, Martyniuk CJ, Prucha MS, Kroll KJ, Denslow ND, Barber DS. Cloning and expression of the translocator protein (18 kDa), voltage-dependent anion channel, and diazepam binding inhibitor in the gonad of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) across the reproductive cycle. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2011;173:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming L, Mann JB, Bean J, Briggle T, Sanchez-Ramos JR. Parkinson’s disease and brain levels of organochlorine pesticides. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:100–3. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gant DB, Eldefrawi ME, Eldefrawi AT. Cyclodiene insecticides inhibit GABAA receptor-regulated chloride transport. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1987;88:313–21. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(87)90206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Reyero N, Barber DS, Gross TS, Johnson KG, Sepúlveda MS, Szabo NJ, et al. Dietary exposure of largemouth bass to OCPs changes expression of genes important for reproduction. Aquat Toxicol. 2006;78:358–69. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelsleichter J, Manire CA, Szabo NJ, Cortes E, Carlson J, Lombardi-Carlson L. Organochlorine concentrations in bonnethead sharks (Sphyrna tiburo) from four Florida estuaries. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2005;48:474–83. doi: 10.1007/s00244-003-0275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore AC. Organochlorine pesticides directly regulate gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene expression and biosynthesis in the GT1-7 hypothalamic cell line. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;192:157–70. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KG, Muller JK, Price B, Ware A, Sepúlveda MS, Borgert CJ, et al. Influence of seasonality and exposure on the accumulation and reproductive effects of p,p′-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane and dieldrin in largemouth bass. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2007;26:927–34. doi: 10.1897/06-336r1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanthasamy AG, Kitazawa M, Kanthasamy A, Anantharam V. Dieldrin-induced neurotoxicity: relevance to Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26:701–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanthasamy AG, Kitazawa M, Yang Y, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy A. Environmental neurotoxin dieldrin induces apoptosis via caspase-3-dependent proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta (PKCdelta): Implications for neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Mol Brain. 2008;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelnikova E, Shkrob MA, Pyatnitskiy MA, Ferlini A, Daraselia N. Novel approach to meta-analysis of microarray datasets reveals muscle remodeling-related drug targets and biomarkers in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamai SL, Warner GF, Walker CH. Effects of dieldrin on life stages of the African catfish, Clarias gariepinus (Burchell) Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1999;42:22–9. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1998.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence LJ, Casida JE. Interactions of lindane, toxaphene and cyclodienes with brain-specific t-butylbicyclophosphorothionate receptor. Life Sci. 1984;35:171–8. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire G, Mnif W, Mauvais P, Balaguer P, Rahmani R. Activation of alpha- and beta-estrogen receptors by persistent pesticides in reporter cell lines. Life Sci. 2006;79:1160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk CJ, Awad R, Hurley R, Finger TE, Trudeau VL. Glutamic acid decarboxylase 65, 67, and GABA-transaminase mRNA expression and total enzyme activity in the goldfish (Carassius auratus) brain. Brain Res. 2007a;1147:154–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk CJ, Chang JP, Trudeau VL. The effects of GABA agonists on glutamic acid decarboxylase, GABA-transaminase, activin, salmon gonadotrophin-releasing hormone and tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in the goldfish (Carassius auratus) neuroendocrine brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007b;19:390–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk CJ, Sanchez BC, Szabo NJ, Denslow ND, Sepúlveda MS. Aquatic contaminants alter genes involved in neurotransmitter synthesis and gonadotropin release in largemouth bass. Aquat Toxicol. 2009;95:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk CJ, Feswick A, Spade DJ, Kroll KJ, Barber DS, Denslow ND. Effects of acute dieldrin exposure on neurotransmitters and global gene transcription in large-mouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) hypothalamus. Neurotoxicology. 2010a;31:356–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk CJ, Kroll KJ, Doperalski NJ, Barber DS, Denslow ND. Genomic and proteomic responses to environmentally relevant exposures to dieldrin: indicators of neurodegeneration? Toxicol Sci. 2010b;117:190–9. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk CJ, Kroll KJ, Doperalski NJ, Barber DS, Denslow ND. Environmentally relevant exposure to 17alpha-ethinylestradiol affects the telencephalic proteome of male fathead minnows. Aquat Toxicol. 2010c;98:344–53. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk CJ, Alvarez S, Lo BP, Elphick JR, Marlatt VL. Hepatic protein expression networks associated with masculinization in the female fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) J Proteome Res. 2012;11:4147–61. doi: 10.1021/pr3002468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean J, Nuñez JL. 17alpha-Estradiol is neuroprotective in male and female rats in a model of early brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin A, Egorov S, Daraselia N, Mazo I. Pathway studio—the analysis and navigation of molecular networks. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2155–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popesku JT, Martyniuk CJ, Mennigen J, Xiong H, Zhang D, Xia X, et al. The goldfish (Carassius auratus) as a model for neuroendocrine signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;293:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveros JC. VENNY. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn Diagrams. 2007 http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html.

- Rewal M, Jung ME, Simpkins JW. Role of the GABA-A system in estrogen-induced protection against brain lipid peroxidation in ethanol-withdrawn rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1907–15. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000148100.78628.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo-Attwood T, Kroll KJ, Denslow ND. Differential expression of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) estrogen receptor isotypes alpha, beta, and gamma by estradiol. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;218:107–18. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Ramos J, Facca A, Basit A, Song S. Toxicity of dieldrin for dopaminergic neurons in mesencephalic cultures. Exp Neurol. 1998;150:263–71. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayan S, Ramakant Satyanarayan A. Bioaccumulation studies of organochlorinated pesticides in tissues of Cyprinus carpio. J Environ Sci Health B. 2005;40:397–412. doi: 10.1081/pfc-200047572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz C, Braak H, Braak E. A sex difference in neurodegeneration of the human hypothalamus. Neurosci Lett. 1996;212:103–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12787-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz C, Ghebremedhin E, Braak E, Braak H. Sex-dependent cytoskeletal changes of the human hypothalamus develop independently of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1999;160:186–93. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salierno JD, Kane AS. 17alpha-ethinylestradiol alters reproductive behaviors, circulating hormones, and sexual morphology in male fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) Environ Toxicol Chem. 2009;28:953–61. doi: 10.1897/08-111.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simunovic F, Yi M, Wang Y, Stephens R, Sonntag KC. Evidence for gender-specific transcriptional profiles of nigral dopamine neurons in Parkinson disease. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ. Diverse neurotoxicants converge on gene expression for neuropeptides and their receptors in an in vitro model of neurodifferentiation: effects of chlorpyrifos, diazinon, dieldrin and divalent nickel in PC12 cells. Brain Res. 2010;1353:36–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takazawa Y, Tanaka A, Shibata Y. Organochlorine pesticides in muscle of rainbow trout from a remote Japanese lake and their potential risk on human health. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2008;187:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tomy S, Wu GC, Huang HR, Chang CF. Age-dependent differential expression of genes involved in steroid signalling pathway in the brain of protandrous black porgy, Acanthopagrus schlegeli. Dev Neurobiol. 2009;69:299–313. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau VL, Spanswick D, Fraser EJ, Larivière K, Crump D, Chiu S, et al. The role of amino acid neurotransmitters in the regulation of pituitary gonadotropin release in fish. Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;78:241–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waye A, Trudeau VL. Neuroendocrine disruption: more than hormones are upset? J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011;14(5–7):270–91. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2011.578273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Knekt P, O’Reilly EJ, Lyytinen J, Reunanen A, Laden F, et al. Persistent organochlorine pesticides in serum and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;74:1055–61. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d76a93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]