Abstract

Compelling evidence indicates that psychiatric and developmental disorders are generally caused by disruptions in the functional connectivity (FC) of brain networks. Events occurring during development, and in particular during fetal life, have been implicated in the genesis of such disorders. However, the developmental timetable for the emergence of neural FC during human fetal life is unknown. We present the results of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging performed in 25 healthy human fetuses in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy (24 to 38 weeks of gestation). We report the presence of bilateral fetal brain FC and regional and age-related variation in FC. Significant bilateral connectivity was evident in half of the 42 areas tested, and the strength of FC between homologous cortical brain regions increased with advancing gestational age. We also observed medial to lateral gradients in fetal functional brain connectivity. These findings improve understanding of human fetal central nervous system development and provide a basis for examining the role of insults during fetal life in the subsequent development of disorders in neural FC.

INTRODUCTION

Accurate neural network formation during the fetal period is recognized as vitally important for healthy central nervous system (CNS) development. However, the timing and order through which neural functional connectivity (FC) networks emerge during human fetal life are unknown. Alterations in neural FC accompany major mental health disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (1,2), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (3,4), schizophrenia (5,6), Alzheimer’s disease (7–9), major depressive disorder (10–12), and posttraumatic stress disorder (13,14). Because disorders of connectivity may originate in fetal life, definitions of connectional architecture must begin in utero.

It is now possible to characterize functional brain circuitry in the human fetus. The detection of temporally correlated, spontaneous fluctuations of the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) allows characterization of the large-scale organization of neural functional brain circuitry. First demonstrated by Biswal and colleagues in 1995 (15), this approach, resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI), can detect functional brain networks, which reflect anatomical organization (16,17) and replicate networks observed during functional tasks (15,18,19). Coherence in BOLD time course data is an index of the strength of functional connections in the brain. Thus, rs-fMRI reveals the configuration of large-scale systems spanning distributed areas [for example, thalamocortical (20), cortical-cingulate (21), and global FC networks (22)] and their connectional strength, measures that would not be accessible in fMRI data obtained during performance of a task. Resting-state FC has been studied and reviewed in infants (23), children (24), and adults (25). Canonical resting-state networks have been observed in infancy (26–31), and the developmental emergence of neural functional connections has been examined in the preterm human brain (26,32,33) Preterm rs-fMRI studies have shown that select brain areas are bilaterally connected in the perinatal period. This has led to development of theory that resting-state networks emerge largely during the period of rapid neural growth in the third trimester of pregnancy, signifying that they form before the acquisition of cognitive competency. However, these observations have been derived from rs-fMRI studies performed in neonates after complicated pregnancies. Rigorous measurement of the ontogeny of functional networks must be done in utero under normal developmental circumstances.

Here, we applied rs-fMRI to empirically evaluate human fetal functional brain connectivity in utero. We quantified cross-hemispheric FC in the second and third trimesters of human fetal life in more than 40 unique source locations (seed regions) in each hemisphere. We took a systematic approach that tested connectivity across numerous spatially discrete cortical regions to obtain data about regional variations in FC strength. Additionally, we tested for evidence of age-related changes in FC across the fetal sample. Finally, we performed independent components analysis (ICA) to validate effects derived from our univariate methods (That is, regression analyses). We specifically recruited women with health pregnancies to participate in the research and followed them through delivery to confirm that their health status was unchanged. We assessed fetal brain FC with the following specific hypotheses: (i) we would observe regional heterogeneity in FC that would support posterior to anterior and medial to lateral developmental gradients, and (ii) we would observe increased strength of cross-hemispheric FC with increasing developmental age. In the context of our results, we discuss the methodological challenges and significance of performing resting-state research in the human fetus.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Clinical characteristics of newborns are provided in Table 1. Ethnicities of pregnanct mothers were 22 black (88%), 2 Causcasian (8%), and 1 multiracial (4%). Frequencies of vaginal delivery and cesarean section were 76 and 24%, respectively. The requencies of epidural anesthesia during delivery were 84 and 16%, respectively. There were more male (n = 17) than female (n = 8) fetuses examined, but χ2 test indicated that this difference was not significant [χ2(1) 1.96, P = 0.2].

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics. Median values are given for Apgar scores.

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal age at MRI (weeks) | 32.1 | 3.95 |

| GA at birth (weeks) | 39.4 | 1.13 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3342 | 453.98 |

| Birth length (cm) | 51 | 1.95 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 34 | 1.90 |

| Baby Apgar at 1 min | 9 | 0.6 |

| Baby Apgar at 5 min | 9 | 0.2 |

| Mother’s age (years) | 23.6 | 4.29 |

Data quality assurance

Fetal rs-fMRI data are summarized in Table 2. On average, we collected 314.1 frames or 10.5 min of data. After removal of high movement frames, we retained x = 184.6 frames per subject or 58.72% of the total data collected. On average, the duration of time that fetal data were continuously collected without movement interruption was 70 s or 35.1 consecutive frames. The average number of breaks or total number of interruptions were introduced into consecutive data acquisition from each subject by excluding data high in movement was 5.2 (SD, 2.2). This calculation includes the break between repeat scans. We did not observe a significant relationship between fetal age and number of frames analyzed [r(25) = 0.27, P = 0.2]. The mean specific absorption rate (SAR), the measure of the heating caused by radio-frequency energy deposition in the body, for all fMRI data sets was 0.218 (SD, 0.0998). See Supplementary Materials and Methods for further discussion of SAR and fetal safety.

Table 2.

Resting-state data summary.

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of rs-fMRI frames collected | 314.4 | 81.80 |

| Total number of rs-fMRI frames analyzed | 184.6 | 61.13 |

| Average consecutive frames | 35.1 | 15.88 |

| Number of breaks | 5.2 | 2.24 |

Data on fetal movement are plotted in Table 3. Average translation (Tx,Ty, Tz) and rotational (Rpitch, Rroll, Ryaw) mean movement were ≤ 0.6 mm and ≤ 1.1 °, respectively. Max excursions, the largest excursions in the time series data, were ≤ 2 mm and ≤ 3.2 ° for translational and rotational movement, respectively. Finally, translational and rotational root mean square (RMS) values were ≤ 0.4 mm and ~0 °, respectively. None of the 18 computed movement parameters were correlated with fetal age; the correlations coefficients (r) and their associated P values are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlations testing between age, fMRI frames analyzed, and movement.

| Mean | SD | Age (r) | Age (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of rs-fMRI frames analyzed | 184.6 | 61.13 | 0.27 | 0.20 |

| Mean x (mm) | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.91 |

| Mean y (mm) | 0.5 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.68 |

| Mean z (mm) | 0.6 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.23 |

| Mean pitch (°) | 0.7 | 0.47 | −0.23 | 0.28 |

| Mean roll (°) | 1.0 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.18 |

| Mean yaw (°) | 1.1 | 0.74 | 0.22 | 0.30 |

| Max excursion x (mm) | 1.6 | 0.55 | −0.17 | 0.43 |

| Max excursion y (mm) | 1.9 | 1.02 | 0.12 | 0.56 |

| Max excursion z (mm) | 2.0 | 0.75 | −0.15 | 0.47 |

| Max excursion pitch (°) | 2.6 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.87 |

| Max excursion roll (°) | 3.0 | 1.21 | 0.27 | 0.19 |

| Max excursion yaw (°) | 3.2 | 1.50 | 0.17 | 0.43 |

| RMS x (mm) | 0.3 | 0.09 | −0.31 | 0.13 |

| RMS y (mm) | 0.3 | 0.12 | −0.32 | 0.12 |

| RMS z (mm) | 0.4 | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.41 |

| RMS pitch (°) | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.93 |

| RMS roll (°) | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.69 |

| RMS yaw (°) | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.94 |

Cross-hemispheric FC

We observed significant bilateral FC in 20 of the 42 cortical regions tested at P ≤ 0.05 after false discovery rate (FDR) correction. FDR was used to minimize type I error (false positive) by shifting significance thresholds to account for multiple comparisons. Graphical depictions of neural connectivity across all fetuses and corresponding FC maps for the sample regions in the left and right hemispheres and anterior and posterior brain regions are provided in Fig. 1. Our graphical depictions display all significant connections, regardless of the slice place, but FC maps render only a single imaging plane. These complementary presentations serve not only to illustrate cross-hemispheric connectivity observed at the group level but also to demonstrate that significant connections are anatomically constrained. That is, FC is not directionally equipotential; connections in the graph depictions are more numerous within a hemisphere, and FC maps contract at the midline. t values that reflect the strength of connectivity for all bilateral pairs are provided in Table 4, along with their associated significance values. Figure 2 illustrates the strength of cortical connectivity across cortical regions by visually depicting the statistical values in Table 4 as color values projected onto a surface rendering of a 30-week-old fetal brain.

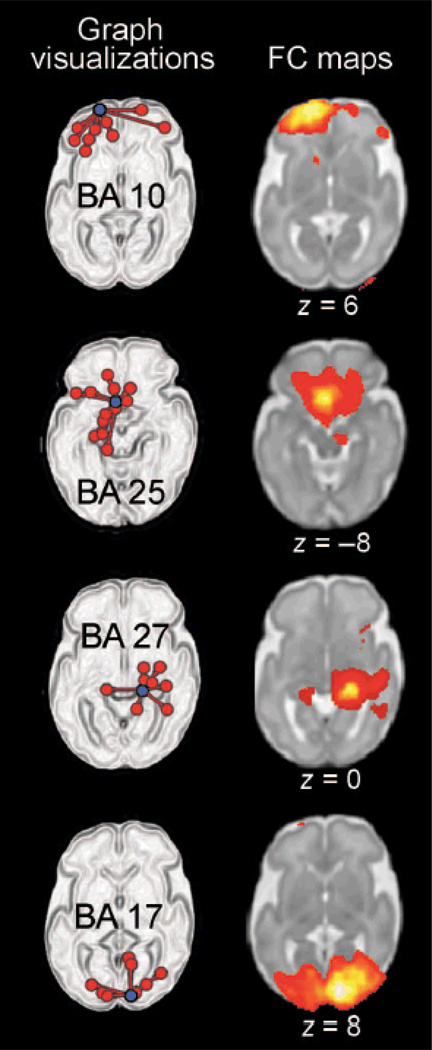

Figure 1.

Graph visualizations and FC maps of neural connectivity in a group of 25 fetuses. On the left, graph visualization depict a single “seed” region of interest (ROI) (in purple) along with all areas significantly functionally connected to that seed region (P < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons). The Brodmann’s area (BA) from which exemplar seeds are drawn is indicated on these graph depictions. FC maps on the right demonstrate the strength of connectivity (P < 0.001) from the same seed region that is depicted to the left but do so within a representative slice. Slice position is given below each FC map, where z = position in axial plane using Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinate space.

Table 4.

Summary of left-right FC across brain areas in the fetus. t stat, statistical t value measured for right-left FC; unc, without correction for multiple comparisons. Asterisk denotes statistical significance.

| BA | Region | t stat | P (unc) | P (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Ventral anterior cingulate | 13.54 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 25 | Subgenual cortex | 13.07 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 33 | Anterior cingulate cortex | 11.01 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 18 | Secondary visual cortex | 10.28 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 31 | Dorsal posterior cingulate | 9.74 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 17 | Primary visual cortex | 9.40 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 7 | Somatosensory association cortex | 9.05 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 23 | Ventral posterior cingulate | 9.00 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 32 | Dorsal anterior cingulate | 7.67 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 5 | Somatosensory association cortex | 7.41 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 8 | Dorsal frontal cortex | 7.15 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 6 | Premotor cortex | 6.47 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 29 | Retrosplenial cingulate | 6.46 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 11 | Orbitofrontal cortex | 4.88 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 30 | Cingulate cortex | 4.64 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 9 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 4.30 | 0.00* | 0.00* |

| 10 | Anterior prefrontal cortex | 4.22 | 0.00* | 0.01* |

| 27 | Piriform cortex | 4.04 | 0.00* | 0.01* |

| 1 | Primary somatosensory | 2.87 | 0.01* | 0.05* |

| 19 | Associative visual cortex | 2.85 | 0.01* | 0.05* |

| 34 | Anterior entorhinal cortex | 2.31 | 0.03* | 0.13 |

| 35 | Perirhinal cortex | 2.06 | 0.05* | 0.18 |

| 37 | Fusiform gyrus | 1.52 | 0.14 | 0.33 |

| 42 | Primary auditory cortex | 1.45 | 0.16 | 0.42 |

| 22 | Superior temporal gyrus | 1.26 | 0.22 | 0.46 |

| 3 | Primary somatosensory cortex | 1.15 | 0.26 | 0.57 |

| 2 | Primary somatosensory cortex | 1.04 | 0.31 | 0.62 |

| 38 | Temporopolar area | 0.96 | 0.35 | 0.63 |

| 4 | Primary motor cortex | 0.95 | 0.35 | 0.75 |

| 47 | Inferior prefrontal cortex | 0.95 | 0.35 | 0.67 |

| 40 | Supramarginal gyrus | 0.94 | 0.36 | 0.69 |

| 39 | Angular gyrus | 0.88 | 0.39 | 0.73 |

| 20 | Inferior temporal gyrus | 0.74 | 0.47 | 0.69 |

| 36 | Parahippocampal cortex | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.75 |

| 28 | Posterior entorhinal cortex | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.81 |

| 41 | Primary auditory cortex | −0.18 | 0.86 | 0.90 |

| 13 | Insular cortex | −0.24 | 0.81 | 0.89 |

| 43 | Subcentral area | −0.73 | 0.47 | 0.76 |

| 45 | Inferior frontal cortex pars triangularis | −1.01 | 0.32 | 0.46 |

| 21 | Middle temporal gyrus | −1.09 | 0.29 | 0.55 |

| 46 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | −1.84 | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| 44 | Inferior frontal cortex pars opercularis | −2.05 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

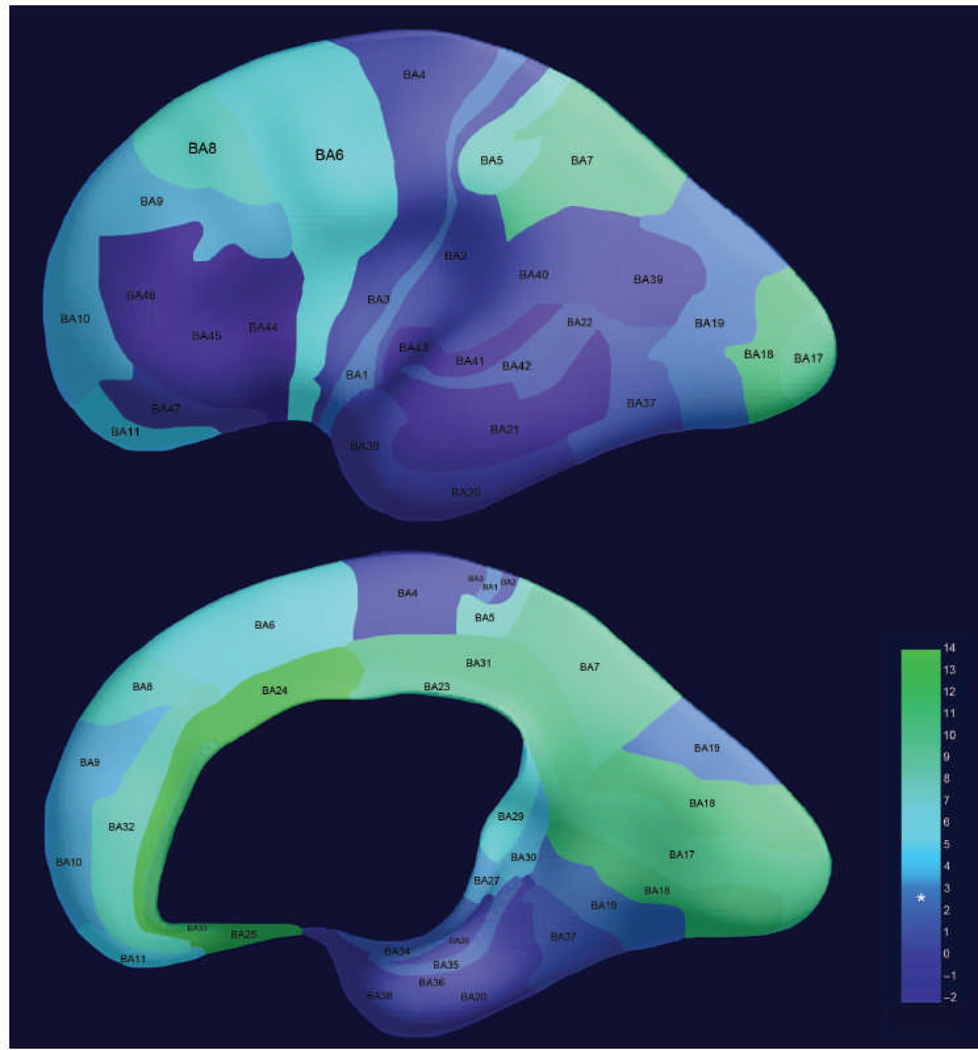

Figure 2.

Regional differences in bilateral FC in 25 fetuses. Strength of right-left connectivity across the group is depicted as a color gradient with higher values corresponding to stronger FC. Asterisk is used to denote the statistical level (t = 2.85) at which measured FC exceeds a significance level of P (FDR) < 0.05. Colors are projected onto a three-dimensional (3D) rendering of the brain of a 30-week-old fetus. The lateral surface of the brain is shown in the top image, whereas the medial surface is shown in the bottom image.

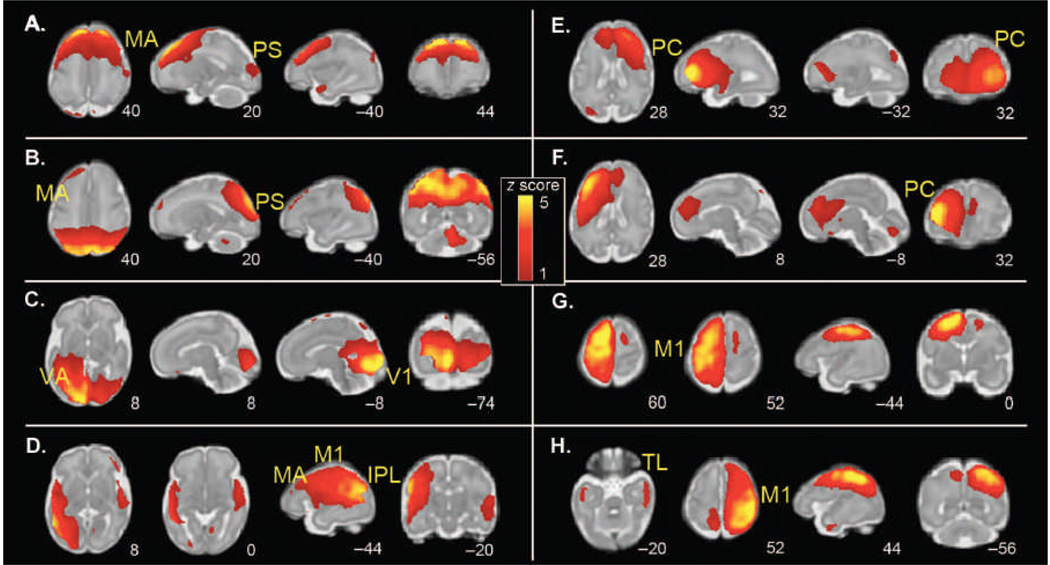

Group ICA of fetal fMRI data yielded eight bilateral neural networks, one unilateral network (Cerebellum, temporal, and frontal cortex), and five networks reflecting noise. Of the eight bilateral networks (Fig. 3), some liked together unimodal (modality-specific) areas such as motor association cortex and peristriate cortex (Fig. 3, A and B) within the same independent component network, and others appeared to be precursors of systems that later merged into larger bilateral networks (for example, primary motor cortex; Fig. 3, G and H). Although ICA classification maximizes statistical independence, numerous pairs within the eight bilaterally represented components had overlapping spatial topology (for example, Fig. 3, A/B, E/F, and G/H), suggesting variation in the interrelatedness of the observed components).

Figure 3.

Group ICA of spontaneous fMRI activity patterns in 25 fetuses (24 to 28 weeks of gestation). Sample axial, sagittal, and coronal slices corresponding to bilaterally represented independent components from ICA are overlaid onto the template of a 32-week fetal brain. The left side of the figure corresponds to the left side of the brain. Coordinates identifying slice locations are provided below each slice using the MNI coordinate space. ICA was used to derive a total of 14 maximally statistically independent brain networks, 8 of which were bilaterally distributed. (A to H) The following networks were detected: (A) motor association (MA) cortex; (B) peristriate (PS) cortex; (C) primary visual (V1) and visual association (VA) cortex; (D) inferior parietal lobule (IPL), primary motor (M1), and motor association cortex; (E) right frontal cortex; (F) left frontal cortex; (G) left primary motor cortex; and (H) right primary motor cortex and bilateral temporal lobe (TL).

Medial-lateral and posterior-anterior connectivity gradients

Strength of FC was significantly correlated with spatial location of the Bas on the medial-lateral axis [r(25) = 0.47, P = 0.002] but not with spatial location of the Bas on the posterior-anterior axis [r(25) = 0.15, P = 0.36].

Age-related changes in bilateral FC

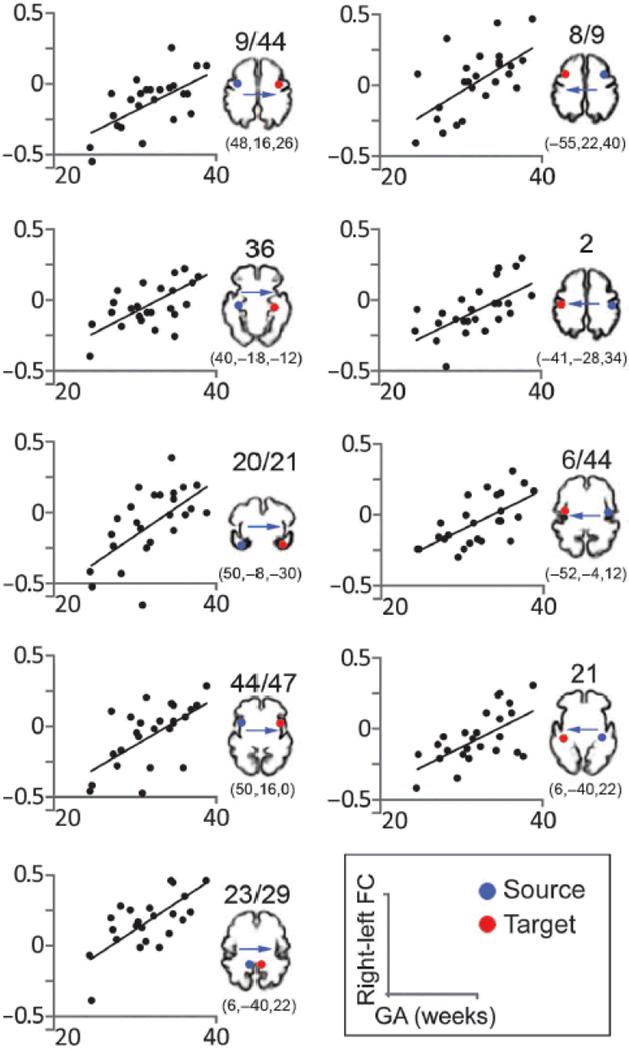

Age and connectivity strength were significantly (P < 0.005) correlated in 80.95% of the cross-hemispheric BA pairs. That is, linear regression analysis of gestational age (GA) and FC isolated significant correlations in fMRI signal changes over time between corresponding voxels in the two hemispheres in 34 of 42 pairs. Age-related increases in bilateral connectivity are plotted for representative areas in Fig. 4. The BA pairs in which FC did not significantly increase with age included BAs, 11, 20, 25, 32, 36, 45, and 46. To more fully address the hypothesis that we would observe FC increases with fetal age, we tested an alternative hypothesis: that FC would significantly decrease with fetal age. The total numbers of voxels that were significant for each area were computed for positive and negative linear regression of GA, and the totals were compared. Paired t test was implemented with boot-strapping, which involves random sampling with replacement from the original data set 10,000 times to attain improved estimates. This test revealed that significantly more voxels were obtained for the positive than for the negative regression with age (P = 0.006).

Figure 4.

Association between strength of bilateral FC and GA of fetuses. Scatter plots depict significant age effects across representative cortical areas. All correlation coefficients r are > 0.6 (Pearson; two-tailed) and P values are ≤ 0.001. Blue dots indicate sources used in SCA (seed) analyses. Red dots indicate approximate contralateral target areas where significant age-related increases in FC were observed. Target FC values and fetal age comprise the scatter plot data points. The precise FC coordinates of the target areas are included below cortical templates of a 32-week-old fetus, which are provided for visual reference. Bas are indicated above the reference images.

DISCUSSION

Here, we systematically examined cross-hemispheric connectivity, measured regional variation in FC, and tested for age-related changes in FC in the human fetus. As hypothesized, the strength of cross-hemispheric FC varied across fetal brain areas. Significant bilateral FC was shown in just less than half of the areas studied (Table 4). Thus, we were able to demonstrate that in the fetal period, about half of the bilateral functional systems of the brain are present to a significant degree, whereas remaining areas remain in more nascent stages. Regional heterogeneity in FC was also observed, with especially high FC noted in medial and posterior brain regions.

We developed a method for ranking cortical regions on medial-lateral and posterior-anterior gradients. We then tested our FC outcome measures against that ranking system. BY means of this ranking procedure, we established support for medial to lateral organization in fetal functional brain connectivity (P = 0.002), confirming previous FC ordering observations in preterm infants (33). The posterior to anterior analysis did not reach statistical significance, although, on average, posterior regions did have higher FC values. The latter finding may be attributable to variations in size and overlap of the source regions in the posterior to anterior axis. Future analyses that evaluate this developmental effect may achieve significance by effectively controlling for the variability introduced by examining ROIs of different sizes.

ICA verified the presence of bilateral FC in the human fetus. With its proven capacity to remove residual noise from BOLD data (34) and lack of reliance on the priori ROIs, ICA provides an alternative procedure for measuring FC in the human fetus. ICA components occupied V1 and visual association cortices, primary motor and motor association cortices, as well as lateral parietal and frontal regions. Also, common spatial territories comprised select pairs of components (Fig. 3, A/B, E/F, and G/H), suggesting a correspondence between particular components that may foreshadow future remodeling in these networks. Overall, ICA validated and expanded upon observations about FC in utero derived using a seed-based connectivity analysis (SCA) approach.

Increasing bilateral FC with increasing age has been demonstrated previously in preterm infants (33) but had not been tested in the human fetus. Demonstration and quantification of processes of FC in utero provides means for evaluating brain development in both health and disease. We offer an evidence-based account of increased cross-hemispheric FC across fetal life to derive better understanding of fetal CNS development and to replicate previous observations, attained by other means, to substantiate the rs-fMRI approach.

Increased symmetry in functional signals may be both a cause and an effect of neuroanatomical development. That is, major segments of cerebral whit matter are formed in fetuses of the ages studies here (35), and the increased structural integrity in these circuits is expected to underlie more effective neural signal transmission. Thus, as the neuroanatomical infrastructure matures, one would expect symmetry in bilateral signals to increase as a result of signaling efficiency. Conversely, the observed neuroanatomical progress may be further modulated via strengthening FC, where spontaneous synchronized neuronal activity would be expected to reinforce the establishment of anatomical connections (36).

Perinatal rs-fMRI studies off enormous potential for evaluating functional brain networks in both health and disease, but the challenges inherent in the methodology warrant discussion. In pioneering work by Schöpf and colleagues, it was reported that 87 scanned fetuses without brain abnormalities, 71 data sets (or 81.6% of cases) had to be excluded from analyses because of movement, and as few as 50 data frames were obtained per fetus; movement in the sample and the average number of frames retained were not reported (37). Recent studies evaluating the impact of movement on rs-fMRI data make apparent the critical need to establish quality control standards for developmental fMRI studies (38). Here, we reported total movement levels for retained data that fell well within standard levels reported in the fMRI literature but did so at the cost of losing just under half of all data collected. Not only did we restrict analyses in terms of movement magnitude but also in the quantity of usable data needed for each contributing subject. The latter point is important, because signal-to-noise computations include both the noise (that is, movement) and the total amount of data. Additionally, we summarize nonsignificant relationships between fetal age (our fixed effect for regression modeling) and movement parameters; therefore, we provide evidence that noise was not a significant contributor to age-related FC results. Future fMRI studies in perinatal life are likely to benefit from longer data collection (more than 10.5 min, the average amount obtained here) and development of new movement correction strategies (39) to achieve fMRI data sufficient quality and quantity.

Other major challenges to this methodology are potential sample selection bias and effects of anesthesia on FC. MRI examinations in fetuses and newborns are often only performed when an abnormality is suspected (37), and as a result, criteria for normality in perinatal MRI data are scarce (40). Then, of the handful of perinatal rs-fMRI studies that have been performed, many include use of sedatives during the MRI exam. The administration of sedatives influences both FC (41,42) and behavioral development (43,44), making the anesthesia approach less desirable experimentally and for mitigating potential risks.

Many developmental disabilities such as mental retardation, cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders, epilepsy, and others are thought to originate during gestation and may co-occur (45–47). A major problem in studying disorders with etiologic roots in pregnancy and the perinatal period is that they are often diagnosed years after exposure, which makes it difficult to identify antecedents. Accordingly, the identification of early biomarkers, particularly those that can be measured prenatally, is important for studying neurobehavioral development. The present study demonstrates the use of rs-fMRI for evaluating the development of brain networks in utero.

The study limitations merit mention. First, the total acquisition time for BOLD fMRI in the sample was 10.5 min on average. Our quality standards necessitated discarding 41% of the data. Numerous rs-fMRI studies in children/adults have described removing data, but many do not report the proportion that was removed. One recent rs-fMRI methodological paper removed 35 to 39% of data to demonstrate the improvements associated with removing frames high in motion (38). Although 41% is only slightly higher than values reported in the literature, this is costly scan time that could be otherwise allocated. This concern can be expanded further to the overall need to establish the optimal acquisition and analyses strategies (for example, spatial and temporal resolution, minimum data, and artifact detection procedures) for fetal whole-brain fMRI. Future development of fetal fMRI research requires systematic evaluation of imaging parameters as well as processing pipelines for establishing optimal and reproducible results For example, we used a slice thickness of 4 mm for the present study, but future studies that use thinner slices may achieve better spatial resolution for the fetal brain. Second, although the negative effect of movement on estimates of FC has been well established (38), the impact of data denoising (such as scrubbing and whitening) on FC has not been thoroughly studied. In the present analysis, we report the “number of breaks”, defined as the number of interruptions to continuous data sampling. The error associated with these denoising processes or with combining rs-fMRI data across repeat scans is an area that warrants further investigation. Finally, as with many fMRI studies, the small sample size poses an additional possible source of error. Nonetheless, our results and sample size align very well with extant literature, especially newborn (term and preterm) rs-fMRI studies (23, 26–30, 33, 48) and ex vivo fetal anatomical studies (49–51).

Our study focused exclusively on regional and age-related variation in interhemispheric FC in the human fetal brain. During early development, the corpus callosum, a large bundle of neural fibers, physically connecting the hemispheres, is formed, facilitating the development of interhemispheric communication. Most of the fibers in the corpus callosum connect homologous regions in each hemisphere (52), but there is evidence that during development transient callosal fibers connect nonhomologous, or noncorresponding, regions in each hemisphere (53). Strong connectivity between the same anatomical areas in opposite hemispheres is likely to subserve cognitive and sensorimotor processes that require integration between the hemispheres, whereas cognitive processes that are highly lateralized, such as language and spatial attention (54), may be more reliant on the development of connections within hemispheres (intrahemispheric connectivity). Recent studies in adults (55,56) and in children (57) have begun to quantify interactions between inter- and intrahemispheric FC. The relationship of inter- to intrahemispheric FC has not been studied in the fetal brain thus far, and such studies will be important to understand brain FC and how it relates to the emergence of cognitive and sensorimotor processes.

Here, we have characterized bilateral connectivity across the fetal brain in healthy pregnancies and provided a detailed account of data quality standards in BOLD imaging of the moving ≥ 24-week human fetus. Future research is needed to examine anatomical and functional brain networks across gestational development, in both health and disease, and to link fetal brain development to infant mental health outcomes. Participants should be followed longitudinally with assessments of developmental progress. In addition to linking neurodevelopmental maturation in utero to sensorimotor and cognitive progress after birth, future studies should examine the potential for environmental factors such as stress to modulate those relationships.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Twenty-nine women (ages 19 to 34; mean age, 23.6; SD, 4.29) underwent MRI once between their 24th and 39th week of pregnancy. The mean age of the fetuses was 32.1 weeks GA (SD, 3.95). Ultrasound examination administered by study physician (E.H.-A.) was performed within 1 week of MRI exam to determine fetal GA. All women provided written informed consistent before undergoing MRI examination. Participation was approved by the Internal Review Board of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and by the Human Investigation Committee of Wayne State University. Singleton, uncomplicated pregnancies with normal ultrasound examination reporting no contraindications for MRI were eligible to participate. The Supplementary Materials include detailed description of the recruitment procedure, as well as discussion regarding fetal safety during MRI (58–69). The MRI examination lasted 45 min. Study participants were followed longitudinally to assure that they developed no complications during pregnancy.

Image acquisition

Because procedural protocols were revised during the pilot phase of this study, for a small number of data sets, there was variation in the MRI system used and in total number of resting-state frames acquired. Total average frame acquisition numbers are reported below. SAR was extracted from fMRI scans for every subject.

For 26 participants, fetal MR exams were performed with a Siemens Verio 70-cm open-bore 3-T scanner with a light-weight (~550 g) abdominal 4-Channel Siemens Flex Coil. Images were collected with the following parameters and computed SAR values: (i) [repetition time/echo time (TR/TE), 20/4.2 ms; 10-mm thickness; SAR = 0.21]; (ii) T2 anatomical (TR/TE, 3500/140 ms; 3-mm slice thickness; repeated four times; SAR = 0.53); (iii) diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (TR/TE, 8800/110 ms; 2-mm slice thickness; axial; SAR = 0.27); (iv) echo planar imaging (EPI) BOLD (TR/TE, 2000/30 ms; 180 frames; 4-mm slice thickness; axial; repeated twice; SAR = 0.21); (v) susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) (TR/TE, 30/21.2 ms; 4-mm slice thickness; SAR = 0.06). After assessing fMRI data quality, 4 of the 26 3-T fetal data sets were excluded from analyses.

For three participants, fetal MR exams were performed with a GE Signa 1.5-T scanner using an eight-channel cardiac coil. Images were collected with the following parameters and computed SAR values: (i) localizer (TR/TE, 5.1/1.5 ms; 6-mm thickness); (ii) T2 anatomical (TR/TE, 1192/103.9 ms; 3-mm slice thickness; repeated four times; SAR = 1.14); (iii) DTI (TR/TE, 12500/116 ms; 2.5-mm slice thickness; axial; SAR = 0.26); (iv) EPI BOLD (TR/TE, 2000/50 ms; 220 frames; 4-mm slice thickness; axial; repeated twice; SAR = 0.02); (v) SWI (TR/TE, 105/16.8 ms; 5-mm slice thickness; SAR = 0.01).

Functional data preprocessing

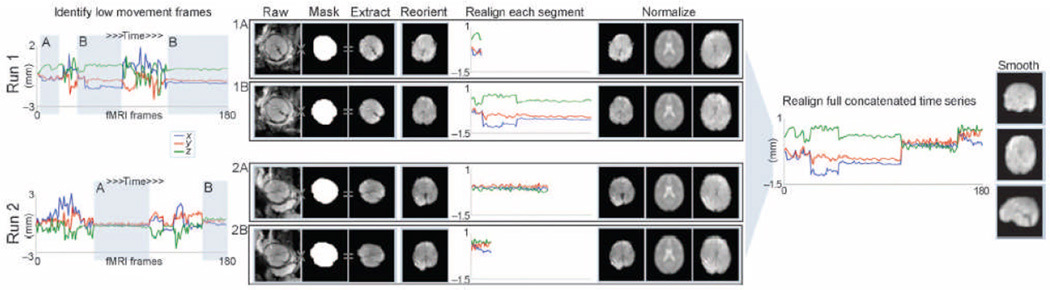

FSL image viewer (70) was used to identify time frames corresponding to periods of minimal head motion in the fetus. BrainSuite (71) was used to manually draw 3D masks on reference functional images from each segment of low movement. Masks were binarized and then applied only to frames corresponding to their select segment, and only those data were extracted and retained for further analyses. Each segment was then manually reoriented, realigned, resliced, and normalized. To correct for variations in normalization between segments, normalized images were then concatenated into one run, realigned, and smoothed. The number of frames retained for all subject was within 1.5 SDs of the mean for the group to limit variation in statistical power across the sample. We tested for relationships between age (fixed effect of interest) and number of retained frames. SPM8 (72) was used for manual spatial reorientation of fetal brain volumes, motion realignment, and normalization and for resampling fetal neural data to a resolution of 2 mm3. Transformation parameters used for normalization were calculated for each block of continuous data collection. Data were normalized to the SPM8 EPI template (72) in MNI space. Other normalization, data for the complete run were concatenated and realigned, and an 8-mm full width half-maximum Gaussian smoothing kernel was applied. The data preprocessing procedure is summarized in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Fetal fMRI data preprocessing. Periods of time corresponding to low movement frames (shaded, gray background) were selected for each fetus and for each fun. Low movement frames were retained for further analysis. Masks were used to extract the fetal brain from surrounding tissue. Fetal fMRI brain data were then manually rotated (reoriented) into a standard position. Reoriented brain data were then processed using standard procedures for preparing functional MRI data for group analyses.

Movement

The translational (Tx, Ty, Tz) and rotational (Rpitch, Rroll, Ryaw) components of movement were calculated separately for retained time frames. We calculated (i) average movement across the data or “mean movement”, (ii) the mean of the maximum frame-to-frame displacement across the data or “max excursion”, and (iii) the mean of the SD for all frames after linear detrending or RMS. Thus, we used a total of 18 movement parameters (3 described above, for each of 3 translation and 3 rotation dimensions) for quantifying total movement in each fetus after correction. Bivariate Pearson correlation was used to test whether fetal age was related to estimated differences in movement related error.

Seed-based connectivity analysis

FC analysis was implemented with the CONN-fMRI toolbox version 12 (76). The seed-based connectivity approach is effective for extracting connection values between spontaneous signal in a seed (source) region and all other brain voxels. Rather than removing the global signal to reduce spurious noise effects, we used the anatomical component correction (aCompCor) method of estimating and removing noise at the individuals voxel level (77,78). Principal components of the signals from white matter and cerebral spinal fluid, as well as the translational and rotational movement parameters (with another six parameters representing their first-order temporal derivatives), were removed with covariate regression analysis. A temporal band-pass filter of 0.01 to 0.08 Hz was applied to investigate low-frequency correlations, which are most consistently produced within this range (79).

A whole-brain connectivity approach was used, wherein the averaged time series from each of 42 bilaterally represented BA anatomical ROIs were extracted. A total of 84 ROIs were defined for each participant with the full BA ROI file provided within the CONN-fMRI toolbox. Bivariate Pearson correlations were calculated from each of these time courses at the voxel level for each fetal functional data set. The resultant individual volume images for each BA were submitted to random-effects modeling in SPM8 and within the CONN-fMRI toolbox (76). One-sample t tests and linear regression were executed in random-effects analyses to obtain group-level cross-hemispheric connectivity and areas of significant age-related FC, respectively. To test the hypothesis that FC to the contralateral hemisphere increases with GA, we performed linear regressions between each BA (Seed) region and voxels occupying the same (homologous) area in the contralateral hemisphere. Boundaries for what constituted the homologous area in the contralateral hemisphere were determined by performing one-sample t tests for all BA regions studied (84 seed regions), then saving thresholded and binarized 3D FC maps, and restricting linear regression to these territories. A threshold of P ≤ 0.05 corrected, with a minimum cluster (k) size of 150 voxels, was used for defining these contralateral spatial boundaries. Linear regressions were thresholded at a significance level of P ≤ 0.005.

Independent components analysis

In addition to the SCA described above, we submitted all data to an ICA-based analytic procedure to further validate group-level cross-hemispheric FC in the fetal brain. ICA provides a means for decomposing rs-fMRI data into unique components optimized according to a criterion of spatial independence. ICA is an alternative means for separating fMRI noise (for example, gross motion, eye movements, and cardiac-induced pulsatile artifact at the base of the brain) from meaningful neural signals (80). The process of ICA yields component maps that summarize signals from noise (for example, distribution in cerebral spinal fluid, ventricles, ring outside cortical surface, and high-frequency power spectrum) as well as sparsely distributed spatial patterns reflecting neural network functional coherence. After preprocessing steps shown in Fig. 5 were completed, data from all participants were concatenated and submitted to group ICA (81). GIFT software (82) was used to estimate 14 maximally statistically independent component neural networks using the informax approach (83). In previous resting-state research in infants, 18 components were estimated (48); we lessened this number to mitigate the risk of overfitting the data, because this has potential for degrading ICA estimation (84).

Medial-lateral and anterior-posterior rank ordering of Bas

To test whether the strength of bilateral FC follows medial-lateral or posterior-anterior spatial gradients, we developed a strategy for generating values depicting the spatial organization of the 42 Bas that were tested. The Bas were rank-ordered by five independent raters (including M.E.T., S.S., and M.T.D.) on the basis of their spatial location along the medial-lateral axis and separately along the posterior-anterior axis. Rank positions were exclusive, and no areas were skipped. Rank values were averaged to obtain representative rank. Rankings were evaluated after rounding decimals to tenths. Ranks were compared to FC t statistics for bilateral pairs with Pearson product-moment correlations coefficient.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Papiez and H. Marusak for assistance rating spatial organization of BAs; Z. Latif, Y. Xuan, J. Neelavalli, Y. Ye, and G. H. Glover for their assistance in technical aspects of scan data acquisition; and K. Quednau, K. Martin, K. Kowelski, A. Bedway, A. Daher, R. Elias, K. Kowelski, A. M. Villa, and M. Salari for their assistance in data collection and participant care. We thank G. H. Baldwin, B. Rihan, H. Nguyen, K. Martin, and T. Lozon for assistance in data management and analyses. We thank L. Nikita, A. Elsey, and J. Bieda for assistance with participant recruitment and communication. We thank the pregnant mothers that chose to participate in this research project and acknowledge their expression of desire to help other mothers and babies to be born healthy. Additionally, we acknowledge the critical analysis provided by the Reviewers and the Science Translational Medicine Editorial Staff and thank them for their contribution to the work. Funding: This research was supported, in part, by the Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute for Child and Family Development; the Department of Pediatrics, Wayne State University (WSU) School of Medicine; the WSU Perinatal Initiative; and the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services through contract N01-HD-2-3342. This project was also supported by NIH/NINDS R01 grant NS 055064 (to C.S.), WSU’s Perinatology Virtual Discovery Grant (made possible by W. K. Kellogg Foundation award P3018205), and WSU’s Research Grant Program awards (to M.E.T.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the NIH.

Footnotes

Author contributions: M.E.T. designed experiments and analysis strategies and provided funding; M.E.T., M.T.D., L.Y., and R.R. wrote the paper; M.E.T., M.T.D., S.S., A.L.A., and C.S. analyzed the data; M.E.T., M.T.D., S.S., Y.K., M.A., A.L.A., L.Y., S.M., and J.-W.J. conducted the experiments; S.M. reviewed fetal neuroanatomy for abnormalities; M.A., A.L.A., E.H.-A., S.S.H., and R.R. oversaw participant recruitment; R.R. served as a senior advisor on the work. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Monk CS, Peltier SJ, Wiggins JL, Weng SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, Lord C. Abnormalities of intrinsic functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage. 2009;47:764–772. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weng SJ, Wiggins JL, Peltier SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, Lord C, Monk CS. Alterations of resting state functional connectivity in the default network in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. 2010;1313:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao Q, Zang Y, Sun L, Sui M, Long X, Zou Q, Wang Y. Abnormal neural activity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1033–1036. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000224769.92454.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian L, Jiang T, Wang Y, Zang Y, He Y, Liang M, Sui M, Cao Q, Hu S, Peng M, Zhuo Y. Altered resting-state functional connectivity patterns of anterior cingulate cortex in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;400:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bluhm RL, Miller J, Lanius RA, Osuch EA, Boksman K, Neufeld RW, Théberge J, Schaefer B, Williamson P. Spontaneous low-frequency fluctuations in the BOLD signal in schizophrenic patients: Anomalies in the default network. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:1004–1012. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bluhm RL, Miller J, Lanius RA, Osuch EA, Boksman K, Neufeld RW, Théberge J, Schaefer B, Williamson PC. Retrosplenial cortex connectivity in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2009;174:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: Evidence from functional MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rombouts S, Scheltens P. Functional connectivity in elderly controls and AD patients using resting state fMRI: A pilot study. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:115–116. doi: 10.2174/1567205053585783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, Liang M, Wang L, Tian L, Zhang X, Li K, Jiang T. Altered functional connectivity in early Alzheimer’s disease: A resting-state fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007;28:967–978. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greicius MD, Flores BH, Menon V, Glover GH, Solvason HB, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Schatzberg AF. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depression: Abnormally increased contributions from subgenual cingulate cortex and thalamus. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;62:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton JP, Chen G, Thomason ME, Schwartz ME, Gotlib IH. Investigating neural primacy in major depressive disorder: Multivariate Granger causality analysis of resting-state fMRI time-series data. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:763–772. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton JP, Furman DJ, Chang C, Thomason ME, Dennis E, Gotlib IH. Default mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: Implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;70:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bluhm RL, Williamson PC, Osuch EA, Frewen PA, Stevens TK, Boksman K, Neufeld RW, Théberge J, Lanius RA. Alterations in default network connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder related to early-life trauma. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34:187–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang HH, Zhang ZJ, Tan QR, Yin H, Chen YC, Wang HN, Zhang RG, Wang ZZ, Guo L, Tang LH, Li LJ. Psychopathological, biological, and neuroimaging characterization of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of a severe coalmining disaster in China. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010;44:385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skudlarski P, Jagannathan K, Calhoun VD, Hampson M, Skudlarska BA, Pearlson G. Measuring brain connectivity: Diffusion tensor imaging validates resting state temporal correlations. Neuroimage. 2008;43:554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, Glahn DC, Fox PM, Mackay CE, Filippini N, Watkins KE, Toro R, Laird AR, Beckmann CF. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:13040–13045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905267106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomason ME, Chang CE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD, Greicius MD, Gotlib IH. Default-mode function and task-induced deactivation have overlapping brain substrates in children. Neuroimage. 2008;41:1493–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fair DA, Bathula D, Mills KL, Dias TG, Blythe MS, Zhang D, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Stevens AA, Nigg JT, Nagel BJ. Maturing thalamocortical functional connectivity across development. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2010;4:10. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly AM, Di Martino A, Uddin LQ, Shehzad Z, Gee DG, Reiss PT, Margulies DS, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Development of anterior cingulate functional connectivity from late childhood to early adulthood. Cereb. Cortex. 2009;19:640–657. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fair DA, Dosenbach NUF, Church JA, Cohen AL, Brahmbhatt S, Miezin FM, Barch DM, Raichle ME, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. Development of distinct control networks through segregation and integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:13507–13512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705843104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smyser CD, Snyder AZ, Neil JJ. Functional connectivity MRI in infants: Exploration of the functional organization of the developing brain. Neuroimage. 2011;56:1437–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uddin L, Supekar K, Menon V. Typical and atypical development of functional human brain networks: Insights from resting-state fMRI. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2010;4:21. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damaraju E, Phillips JR, Lowe JR, Ohls R, Calhoun VD, Caprihan A. Resting-state functional connectivity differences in premature children. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2010;4:23. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fransson P, Aden U, Blennow M, Lagercrantz H. The functional architecture of the infant brain as revealed by resting-state fMRI. Cereb. Cortex. 2011;21:145–154. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fransson P, Skiöld B, Engström M, Hallberg B, Mosskin M, Aden U, Lagercrantz H, Blennow M. Spontaneous brain activity in the newborn brain during natural sleep—An fMRI study in infants born at full term. Pediatr. Res. 2009;66:301–305. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181b1bd84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao W, Zhu H, Giovanello KS, Smith JK, Shen D, Gilmore JH, Lin W. Evidence on the emergence of the brain’s default network from 2-week-old to 2-year-old healthy pediatric subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:6790–6795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811221106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin W, Zhu Q, Gao W, Chen Y, Toh CH, Styner M, Gerig G, Smith JK, Biswal B, Gilmore JH. Functional connectivity MR imaging reveals cortical functional connectivity in the developing brain. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1883–1889. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu WC, Flax JF, Guise KG, Sukul V, Benasich AA. Functional connectivity of the sensorimotor area in naturally sleeping infants. Brain Res. 2008;1223:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doria V, Beckmann CF, Arichi T, Merchant N, Groppo M, Turkheimer FE, Counsell SJ, Murgasova M, Aljabar P, Nunes RG, Larkman DJ, Rees G, Edwards AD. Emergence of resting state networks in the preterm human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:20015–20020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007921107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smyser CD, Inder TE, Shimony JS, Hill JE, Degnan AJ, Snyder AZ, Neil JJ. Longitudinal analysis of neural network development in preterm infants. Cereb. Cortex. 2010;20:2852–2862. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kochiyama T, Morita T, Okada T, Yonekura Y, Matsumura M, Sadato N. Removing the effects of task-related motion using independent-component analysis. Neuroimage. 2005;25:802–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kostović I, Judas M, Rados M, Hrabac P. Laminar organization of the human fetal cerebrum revealed by histochemical markers and magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb. Cortex. 2002;12:536–544. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shatz CJ. Emergence of order in visual system development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:602–608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schöpf V, Kasprian G, Brugger PC, Prayer D. Watching the fetal brain at ‘rest’. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2012;30:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seshamani S, Fogtmann M, Thomason M, Studholme C. paper presented at the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; Melbourne, Australia. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tilea B, Alberti C, Adamsbaum C, Armoogum P, Oury JF, Cabrol D, Sebag G, Kalifa G, Garel C. Cerebral biometry in fetal magnetic resonance imaging: New reference data. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;33:173–181. doi: 10.1002/uog.6276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonhomme V, Boveroux P, Hans P, Brichant JF, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Boly M, Laureys S. Influence of anesthesia on cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic rate, and brain functional connectivity. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2011;24:474–479. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834a12a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boveroux P, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Bruno MA, Noirhomme Q, Lauwick S, Luxen A, Degueldre C, Plenevaux A, Schnakers C, Phillips C, Brichant JF, Bonhomme V, Maquet P, Greicius MD, Laureys S, Boly M. Breakdown of within- and between-network resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging connectivity during propofol-induced loss of consciousness. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1038–1053. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f697f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kellogg CK. Sex differences in long-term consequences of prenatal diazepam exposure: Possible underlying mechanisms. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1999;64:673–680. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicosia A, Giardina L, Di Leo F, Medico M, Mazzola C, Genazzani AA, Drago F. Long-lasting behavioral changes induced by pre- or neonatal exposure to diazepam in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;469:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paneth N, Hong T, Korzeniewski S. The descriptive epidemiology of cerebral palsy. Clin. Perinatol. 2006;33:251–267. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paneth N, Korzeniewski SJ, Hong T. The role of the intrauterine and perinatal environment in cerebral palsy. NeoReviews. 2005;6:e133–e140. [Google Scholar]

- 47.The definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007;49:1–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fransson P, Skiöld B, Horsch S, Nordell A, Blennow M, Lagercrantz H, Aden U. Restingstate networks in the infant brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:15531–15536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704380104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huttenlocher P. Synaptic density in human frontal cortex—Developmental changes and effects of aging. Brain Res. 1979;163:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huttenlocher P. Morphometric study of human cerebral cortex development. Neuropsychologia. 1990;28:517–527. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(90)90031-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yakovlev PI, Lecours AR. In: Regional Development of the Brain in Early Life. Minkowski A, editor. Oxford: Blackwell; 1967. pp. 3–70. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dougherty RF, Ben-Shachar M, Bammer R, Brewer AA, Wandell AB. Functional organization of human occipital-callosal fiber tracts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:7350–7355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500003102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Innocenti GM, Clarke S. Bilateral transitory projection to visual areas from auditory cortex in kittens. Brain Res. 1984;316:143–148. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toga AW, Thompson PM. Mapping brain asymmetry. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:37–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gee DG, Biswal BB, Kelly C, Stark DE, Margulies DS, Shehzad Z, Uddin LQ, Klein DF, Banich MT, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Low frequency fluctuations reveal integrated and segregated processing among the cerebral hemispheres. Neuroimage. 2011;54:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stark DE, Margulies DS, Shehzad ZE, Reiss P, Kelly AM, Uddin LQ, Gee DG, Roy AK, Banich MT, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Regional variation in interhemispheric coordination of intrinsic hemodynamic fluctuations. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:13754–13764. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4544-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friederici AD, Brauer J, Lohmann G. Maturation of the language network: From inter- to intrahemispheric connectivities. PLoS One. 2011;6:20726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Wilde JP, Rivers AW, Price DL. A review of the current use of magnetic resonance imaging in pregnancy and safety implications for the fetus. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2005;87:335–353. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dimbylow P. SAR in the mother and foetus for RF plane wave irradiation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007;52:3791–3802. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/13/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. Criteria for Significant Risk Investigations of Magnetic Resonance Diagnostic Devices; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gowland PA, De Wilde J. Temperature increase in the fetus due to radio frequency exposure during magnetic resonance scanning. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008;53:L15–L18. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/21/L01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hand JW, Li Y, Hajnal JV. Numerical study of RF exposure and the resulting temperature rise in the foetus during a magnetic resonance procedure. Phys. Med. Biol. 2010;55:913–930. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/4/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hand JW, Li Y, Thomas EL, Rutherford MA, Hajnal JV. Prediction of specific absorption rate in mother and fetus associated with MRI examinations during pregnancy. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006;55:883–893. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kikuchi S, Saito K, Takahashi M, Ito K. Temperature elevation in the fetus from electromagnetic exposure during magnetic resonance imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2010;55:2411–2426. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/8/018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kok RD, de Vries MM, Heerschap A, van den Berg PP. Absence of harmful effects of magnetic resonance exposure at 1.5 T in utero during the third trimester of pregnancy: A follow-up study. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2004;22:851–854. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levine D, Zuo C, Faro CB, Chen Q. Potential heating effect in the gravid uterus during MR HASTE imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2001;13:856–861. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reeves MJ, Brandreth M, Whitby EH, Hart AR, Paley MNJ, Griffiths PD, Stevens JC. Neonatal cochlear function: Measurement after exposure to acoustic noise during in utero MR imaging. Radiology. 2010;257:802–809. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10092366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shamsi S, Wu DG, Chen J, Liu R, Kainz W. 2006 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest. San Francisco: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Welsh R, Nemec U, Thomason M. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging at 3.0 T. Topics Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2011;22:119–131. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0b013e318267f932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.FSL. FMRIB Software Library. http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shattuck DW. BrainSuite. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(02)00054-3. http://www.loni.ucla.edu/Software/BrainSuite. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Statistical Parametric Mapping 8 from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging. http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Altaye M, Holland SK, Wilke M, Gaser C. Infant brain probability templates for MRI segmentation and normalization. Neuroimage. 2008;43:721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Serag A, Aljabar P, Ball G, Counsell SJ, Boardman JP, Rutherford MA, Edwards AD, Hajnal JV, Rueckert D. Construction of a consistent high-definition spatio-temporal atlas of the developing brain using adaptive kernel regression. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2255–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi F, Yap PT, Wu G, Jia H, Gilmore JH, Lin W, Shen D. Infant brain atlases from neonates to 1- and 2-year-olds. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Nieto-Castanon A. CONN: Functional connectivity toolbox. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0073. http://www.nitrc.org/projects/conn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Behzadi Y, Restom K, Liau J, Liu TT. A component based noise correction method (CompCor) for BOLD and perfusion based fMRI. Neuroimage. 2007;37:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chai XJ, Castañón AN, Ongür D, Whitfield-Gabrieli S. Anticorrelations in resting state networks without global signal regression. Neuroimage. 2012;59:1420–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van Dijk KRA, Hedden T, Venkataraman A, Evans KC, Lazar SW, Buckner RL. Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: Theory, properties, and optimization. J. Neurophysiol. 2010;103:297–321. doi: 10.1152/jn.00783.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thomas CG, Harshman RA, Menon RS. Noise reduction in BOLD-based fMRI using component analysis. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1521–1537. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Group ICA Toolbox. http://icatb.sourceforge.net/groupica.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2001;14:140–151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bell AJ, Sejnowski TJ. An information-maximization approach to blind separation and blind deconvolution. Neural Comput. 1995;7:1129–1159. doi: 10.1162/neco.1995.7.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Särelä J, Vigário R. Overlearning in marginal distribution-based ICA: Analysis and solutions. J. Machine Learning Res. 2004;4:1447–1469. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.