Abstract

MicroRNAs are now recognized as important regulators of cardiovascular genes with critical roles in normal development and physiology, as well as disease development. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs approximately 22 nucleotides in length that regulate expression of target genes through sequence-specific hybridization to the 3′ untranslated region of messenger RNAs and either block translation or direct degradation of their target messenger RNA. They have been shown to participate in cardiovascular disease pathogenesis including atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure and cardiac arrhythmias. Broadly defined, cardiac arrhythmias are a variation from the normal heart rate or rhythm. Arrhythmias are common and result in significant morbidity and mortality. Ventricular arrhythmias constitute a major cause for cardiac death, particularly sudden cardiac death in the setting of myocardial infarction and heart failure. As advances in pharmacologic, device, and ablative therapy continue to evolve, the molecular insights into the basis of arrhythmia is growing with the ambition of providing additional therapeutic options. Electrical remodeling and structural remodeling are identified mechanisms underlying arrhythmia generation; however, published studies focusing on miRNAs and cardiac conduction are sparse. Recent studies have highlighted the role of microRNAs in cardiac rhythm through regulation of key ion channels, transporters, and cellular proteins in arrhythmogenic conditions. This article aims to review the studies linking miRNAs to cardiac excitability and other processes pertinent to arrhythmia.

Keywords: microRNAs, cardiovascular, arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, conduction, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, electrical remodeling

Introduction

Cardiac arrhythmias have classically been divided into supraventricular or ventricular depending on the origin of the arrhythmic focus. Aside from location, arrhythmias are also classified as bradyarrhythmias, and tachyarrhythmias depending on the rate of the arrhythmic focus. These arrhythmias can be the result of a variety of structural changes or ion channel dysfunction. Regardless of the mechanism, the manifestation of these arrhythmias continues to be a major contributor to human morbidity and mortality. Unstable ventricular arrhythmias secondary to channelopathies significantly increase the risk of sudden cardiac death (1). Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia, with an estimated prevalence of AF is 0.4% to 1% in the general population, increasing with age to approximately 8% in those >80 years (2). Heart failure is a syndrome caused by significant impairments in cardiac function. Sudden death, generally due to arrhythmic causes, is responsible for a significant proportion of deaths among patients with heart failure. Patients with heart failure experience a variety of other significant rhythm abnormalities beyond ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Atrial arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation, are very common in heart failure and can contribute substantially to morbidity and mortality (3). These arrhythmias are a manifestation of diverse abnormalities (electrical, structural, metabolic, neurohormonal, or molecular alterations) in multiple pathological conditions (heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism, aging, etc). Dysregulation or functional impairment of ion channels, transporters, intracellular Ca2+-handling proteins, and other relevant proteins can create structural and metabolic substrates, which have the potential to render electrical disturbances predisposing to conduction abnormalities and arrhythmias (4). Although published studies focusing on miRNAs and cardiac conduction are still sparse, available results have demonstrated the importance of miRNAs in arrhythmia.

Basics of MicroRNA Biology

MicroRNAs are ~22 nucleotide single-stranded RNAs that inhibit the expression of specific mRNA targets through Watson–Crick base pairing between the miRNA and sequences typically located in the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs. Although they do not encode proteins, miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II as part of longer molecules called pri-miRs (approximately 2 kb in length). Pri-miRs are cleaved in the nucleus by the RNase III-type enzyme Drosha to yield a pre-miR, which has a short stem-loop structure consisting of approximately 70 nucleotides (5). This premiR is exported to the cytoplasm, via exportin-5, and further processed by the ribonuclease Dicer to form a double-stranded RNA molecule.

The “passenger strand” of the miRNA duplex is eliminated to leave a single-stranded miRNA, which interact with Argonaute to form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and then guide the RISC to their target mRNAs (6). Target recognition is dependent on the specific interaction between the miR and miR recognition elements (seeds) located in the 3′UTR of target messenger RNAs. In order for a miRNA to elicit functional consequences, the nucleotodes at the 2-8 position at the 5′-end must have exact complementarity to the target mRNA, the so-called ‘seed’ region, and partial complementarity to the rest of its sequence. Finally, translational inhibition or, in some cases, mRNA degradation, contributes to the downregulation of the corresponding target protein (7, 8).

The human genome is estimated to encode more than 1,000 miRNAs, which are either transcribed as stand alone transcripts, often encoding several miRNAs, or generated by the processing of introns of protein-coding genes. MicroRNAs typically exert inhibitory effects on several mRNAs, which often encode proteins that govern the same biological process or several components of a molecular pathway (9, 10). The multiplicity of miRNA targets may also promote combinatorial regulation by miRNAs that individually target various mRNAs whose protein products contribute to one particular regulatory axis. In this model, a biological response would be expected only after co-expression of several miRNAs that cooperatively target various components of a functional network or are all required to sufficiently repress a single target (11, 12). Clearly, miRNA biology is a complex and highly orchestrated mode of gene regulation, potentially impinging on nearly all biological processes in mammals and having particularly important roles in disease states (13). Cardiac specific miRNAs have been shown to regulate a number of critical cellular functions in the developing and normal adult heart (14). Aberrant expression of these miRNAs have also been shown to have dramatic impacts in the development of cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and angiogenesis (15). Not surprisingly, miRNAs are being increasingly recognized as important regulators of cardiac conduction and the development of arrhythmias.

Therapeutic Applications of MicroRNAs

The importance of miRNAs in the maintenance of cardiac function and the development of dysfunction creates opportunities for therapeutic applications of miRNA biology in heart disease. In principle, miRNA mimics can be used to elevate the expression of beneficial miRNAs in disease settings, whereas miRNA inhibitors can be delivered to block the activity of miRNAs that drive disease progression. Thus, identification and validation of miRNA targets is especially important to the development of miRNA-based therapeutics.

Currently, the most widely used approach to regulate miRNA levels in vivo is by using antisense oligonucleotides harboring the full or partial complementary reverse sequence of a mature miRNA that can reduce the levels of a microRNA. Single-stranded oligonucleotides have been shown to be effective in inactivating miRNAs in vivo (16, 17). A novel class of chemically engineered oligonucleotides termed “antagomirs” have been shown to effectively silence miRNA in mice (18). Antagomirs are cholesterol-conjugated single-stranded RNA molecules 21–23 nucleotides in length and complementary to the mature target miRNA. Interestingly, anatgomirs are very stable in vivo and, after one intravenous injection, have the ability to silence target miRNA in the liver, lung, intestine, heart, skin, bone marrow for more than a week.

In addition to modulating miRNA levels by using chemically modified antisense oligonucleotides, modulation of miRNAs could potentially also be established by preventing the miRNA from doing its job by “soaking up” the miRNA. This technique has been named miRNA erasers, sponges, or decoys (19). A vector expressing miRNA target sites can be used to scavenge a miRNA and prevent it from regulating its natural targets. The vectors can harbor multiple miRNA binding sites downstream of a reporter such as green fluorescent protein or luciferase, expressed from a strong promoter, whereby the reporter can indicate whether the miRNA is effectively scavenged away by the decoy. Because the interaction between microRNA and target is largely dependent on base-pairing in the seed region (positions 2–8 of the microRNA), a decoy target should interact with all members of a microRNA family. In so doing, it provides a way to inhibit functional classes of microRNAs as opposed to single microRNA sequences (20). As demonstrated by Care et al, an adenoviral system can be used to deliver to miRNA decoys in cardiac tissue to suppress specific miRNA function (21). As such, current decoy technology can also be used to validate target predictions and assay microRNA loss-of-function phenotypes.

Basics of Cardiac conduction

Cardiomyocytes require strict coordination of excitation, impulse propagation, and repolarization in order to maintain a normal rhythm in sync with the mechanical actions of the heart. Automaticity is a measure of the ability for cells to generate spontaneous action potentials. Conduction refers to the propagation of excitation within a cell and between cells and the velocity by which this occurs is determined by the rate of membrane depolarization and the intercellular conductance. Repolarization refers to the return of membrane resting potential in order to generate another depolarization and the rate of membrane repolarization determines the length of action potential duration (APD) and effective refractory period. This directly impacts the ability to generate the next excitation in a cardiac cell.

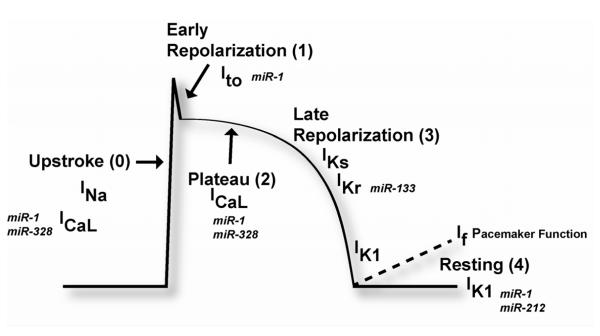

These electrical activities of the heart are orchestrated by multiple categories of ion channels. Four major categories of ion channels exist in cardiac cells, including Na+ channels, Ca2+ channels, K+ channels, and Cl2 channels. The sum of the actions orchestrated by the variety of ion channels and transporters result in a characteristic action potential (AP) (Figure 1). A cardiac AP can be divided into 4 phases beginning with initial rapid depolarization (phase 0) and ending with the return to the resting state (phase 4). A typical cardiac AP contains a long plateau phase (phase 2) distinct from APs in noncardiac cells, but AP from different regions of the heart possesses different morphologies (22, 23). Intricate interplays of all these ion channels maintain the normal heart rhythm. Channelopathies, or dysfunction of the ion channels, which may result from genetic alterations in ion channel genes or aberrant expression of these genes, can render electrical disturbances predisposing to cardiac arrhythmias (4).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the ventricular action potential with ion currents activated during the various phases of the action potential and possible microRNA influence of ion current. INa, fast sodium current; ICaL, calcium current through L-type calcium channels; IKr, rapid delayed rectifier potassium current; IKs, slow delayed rectifier potassium current; Ito, transient outward current; IK1, inward rectifier potassium current.

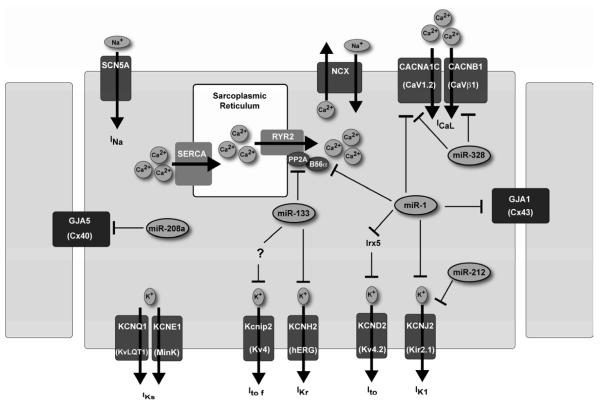

Transmembrane proteins control the movement of ions across the cytoplasmic membrane of cardiomyocytes such as sodium (Na+) channels, which determine the rate of membrane depolarization. Pacemaker channels carry the non-selective cation currents and are critical in generating sinus rhythm and ectopic heart beats as well. Gap junction proteins such as connexins are important for inter-cell conductance of excitation. Calcium channels (L-type Ca2+) account for excitation–contraction coupling and contribute to pacemaker activities in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodal cells. Potassium (K+) channels govern the membrane potential and the rate of membrane repolarization (22) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of ventricular cardiomyocyte ion channels regulated by microRNAs. NCX, sodium-calcium exchanger; SCN5A, sodium channel, voltage-gated, type V, alpha subunit; SERCA, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a. Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release involves the ryanodine receptor (RyR2) channels on the sarcoplasmic reticulum and is essential for activation of contractile filaments during myocardial contraction.

Regulation of cardiac automaticity

Cardiac pacemaker activity sets the rhythm and rate of cardiac chamber contraction. Automaticity is the property of cardiac cells to generate spontaneous action potentials. This spontaneous activity is the result of diastolic depolarization caused by a net inward current during phase 4 of the action potential, which gradually brings the membrane potential to threshold. Pacemaker channels carry the hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker current, If, which is a mixed cationic current carried by Na+ and K+. Almost all spontaneously active cells coming from heart rhythm centers express f-channels (24).

The sinoatrial (SA) node normally displays the highest intrinsic rate. Cells of the SA node express abundant hyperpolarization-activated cation channel HCN genes and T-type Ca2+ channel as well. HCN4 is the predominant f-channel isoform expressed in the SA node and AV node. The HCN1 and HCN2 isoforms are also expressed in these rhythmogenic centers and therefore represent important gene for rhythm generation (25). When the membrane potential reaches certain threshold, T-type Ca2+ channels activate to elicit a spontaneous excitation (24, 25).

Regulation of Cardiac Depolarization

At rest, cardiomyocytes transmembrane potential is −90 mV. Upon activation, depolarization occurs by rapid entry of Na+ through Na+ channels to generate a large inward depolarizing current (INa). Ca2+ entry into the cell through the L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) also contributes to phase 0 depolarization (Figure 1). Voltage-gated Na+ channels are activated by depolarization and are responsible for the rapid upstroke of the cardiac AP. Once threshold depolarization for an AP is reached, the opening of Na+ channels leads to further depolarization, which in turn activates additional Na+ channels and depolarization. The result is a very rapid depolarization toward the electrochemical potential of Na+. Depolarization stops, in part because Na+ channels inactivate, the amplitude of INa decreases and switches off Na+ conductance (26).

SCN5A encodes the α-subunit of the voltage-gated cardiac sodium channel (designated Nav1.5), conducting the cardiac sodium current INa. Nav1.5 is an integral membrane protein involved in the initiation and conduction of action potentials. Mutations in SCN5A, have been associated with a variety of arrhythmic disorders, including long QT, Brugada, and sick sinus syndromes as well as progressive cardiac conduction defect and atrial standstill (27). Moreover, alterations in the Nav1.5 expression level and/or sodium current density have been frequently seen in acquired cardiac disorders, such as heart failure (28).

The CaV1.2 gene (CACNA1C) and CaVβ1 (CACNB1) encode the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel (ICaL) α1c- and β1 subunits, in ventricular myocytes (29). Voltage-gated Cav1 channels (Cav1.2 and Cav1.3) mediate L-type Ca currents that play distinct roles in different cardiac cell-types. Expressed throughout the heart, Cav1.2 regulates action potential duration and excitation-contraction coupling in the ventricle, thus, changes in Cav1.2 channel function have important implications for excitability (30). Cav1.3 is largely absent from the ventricles but is highly expressed in atria, atrioventricular node, and sinoatrial node (31, 32). Ca2+ enters cardiomyocytes via a variety of Ca2+ conductances, of which that carrying L-type Ca2+ current is the most prominent. The membrane density of ICaL channels has been shown to be reduced by cardiac failure (33). Increased Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels has also been implicated in the development of hypertrophy and pathological remodeling of the heart with select stress stimuli. Interestingly, it has been shown that genetically-based reduction in L-type Ca2+ current in mice induced spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy or dramatically enhance hypertrophy after pressure overload stimulation (34).

An example of a human pathological condition associated with aberrant Cav1.2 channel gating is Timothy syndrome, a rare, autosomal dominant, multiorgan disorder caused by de novo gain-of-function missense mutations in exon 8 or an alternatively spliced exon 8A of Cav1.2. Timothy syndrome is characterized by a prolongation of the electrocardiogram QT interval, which is why it is also known as long QT syndrome 8 (LQT8). Timothy syndrome patients commonly suffer sudden cardiac death resulting from lethal cardiac arrhythmias. Accordingly, functional studies revealed that the mutated Ca2+ channel presented a “gain of function” state by impairing open-state voltage-dependent inactivation (35). This may lead to sustained Ca2+ influx, AP prolongation, and Ca2+ overload, which promotes early and delayed afterdepolarizations (36, 37).

A potential role for microRNA regulation of cardiac depolarization was identified when Lu et al utilized computational prediction algorithms to identify CACNA1C and CACNB1 as potential targets for miR-328. Subsequent microRNA microarray analysis and real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction demonstrated an approximate four-fold elevation of miR-328 level in left atrial samples from dogs with AF established by right atrial tachypacing for 8 weeks, and from human atrial samples from AF patients with rheumatic heart disease. Overexpression of miR-328 through adenovirus infection in canine atrium and transgenic approach in mice recapitulated the phenotypes of AF, exemplified by enhanced AF vulnerability, diminished L-type Ca2+ current, and shortened atrial action potential duration. Normalization of miR-328 level with antagomiR reversed the conditions, and genetic knockdown of endogenous miR-328 dampened AF vulnerability. CACNA1C and CACNB1 were established as the cognate target genes for miR-328 by western blot and luciferase activity assay showing the reciprocal relationship between the levels of miR-328 and ICaL channel protein subunits (38).

The role of microRNA regulation of Cav1.2 in cardiac arrhythmias is highlighted in another genetic disorder, myotonic dystrophy, which is the most common muscular dystrophy in adults, is characterized by multiple symptoms including muscle weakness, myotonia, insulin resistance, neuropsychiatric impairment, and cardiac defects. Cardiac involvement in affected individuals can include degeneration of the conduction system leading to fatal atrioventricular blocks. Furthermore, individuals with myotonic dystrophy are also characterized by atrial and ventricular tachyarrythmias (39). Myotonic dystrophy is a RNA gain-of-function disease caused by expanded CUG or CCUG repeats, which sequester the RNA binding protein muscle blind-like protein 1 (MBNL1). In a study by Rau et al, the authors demonstrated an important role for MBNL1 as a cytoplasmic regulator of the biogenesis of pre-miR-1 resulting in pre-miR-1 uridylation thus blocking pre-miR-1 processing from Dicer. Consequently, loss of mature miR-1 increases levels of its targets. Analysis with miRanda predicted various targets of miR-1, including the cardiac L-type calcium channel gene CACNA1C (CAV1.2). The authors confirmed CACNA1C regulation by miR-1 through luciferase reporter assays. Expression of CACNA1C protein was upregulated in myotonic dystrophy heart samples compared to control, whereas CACNA1C mRNA levels were not altered.

Regulation of cardiac repolarization

After depolarization, the membrane potential begins to return toward the resting state. The inward flowing currents such as Na+ and L-type Ca2+ currents tend to depolarize the membrane and delay repolarization to prolong APD, whereas the outward going K+ currents, mainly including IK1, Ito, IKr, and IKs, tend to repolarize the membrane to shorten APD (Figure 1). Cardiac repolarization is determined by an intricate interplay and a delicate balance between inward and outward ion currents. Membrane depolarization is immediately followed by a brief rapid repolarization phase (phase 1) due to K+ efflux through a rapidly activating and inactivating transient outward K+ current (Ito). During the characteristic plateau phase (phase 2), there is a balance between inward currents ICaL and INa and outward K+ currents. There are progressive time-dependent sequential activations of delayed rectifier K+ currents, first the rapid delayed rectifier K+ current (IKr) and then the slow delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs). IKr acts to terminate the AP with an appropriate delay by producing rapid phase 3 repolarization, and IKs serves as a repolarization reserve to prevent excessive slowing of repolarization (40). Finally, inward rectifier K+ current (IK1) aids to complete the terminal phase of repolarization.

The rate of repolarization importantly affects the likelihood of developing arrhythmias. Slowly activating delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs) along with its underlying channel proteins KCNQ1 (pore-forming α-subunit) and KCNE1 (auxiliary β-subunit) importantly affect cardiac action potential duration and arrhythmogenesis through two mechanisms. First, IKs acts as a powerful repolarization reserve or safety factor to restrict excessive cardiac action potential duration and QT prolongation caused by other factors (41, 42). Second, a varying density of repolarizing K+ currents within the ventricular myocardium creates a spatial heterogeneity of cardiac repolarization (43). The distribution of IKs in the heart follows important spatial patterns across the myocardium from epicardium to endocardium, interventricular from RV to LV, across the interventricular septum, and an apex to base difference (44, 45). These intrinsic patterns of distribution are important in maintaining the sequential excitation of cardiac muscles. Disruption of the patterns and/or exaggeration of the regional heterogeneity can create substrates for arrhythmogenesis.

One of the earliest evidence for miRNA regulation of cardiac repolarization came from Zhou et al in 2007 with a targeted deletion of miR-1-2 in mice. This resulted in 50% lethality that was largely attributable to ventricular septal defects. However, approximately half of the surviving mutant animals died suddenly and revealed electrophysiological defects manifested by conduction block. Surface electrocardiography in mutant mice demonstrated a reduced average heart rate, accelerated atrioventricular conduction (reflected by the shortened PR interval), and slowed ventricular conduction (manifested by the widened QRS complex) (46). The authors identified Irx5 as a target for miR-1-2. Irx5 belongs to the Iroquois family of homeodomain-containing transcription factors that regulate cardiac repolarization by repressing transcription of KCND2. KCND2 encodes a K+ channel subunit (Kv4.2) responsible for transient outward K+ current (Ito) that is the major determinant for the transmural repolarization gradient in the ventricular wall (47). The increase in Irx5 protein levels in miR-1-2 mutants corresponded with a decrease in KCND2 expression. The authors concluded that the loss of Irx5 disrupted ventricular repolarization with a predisposition to arrhythmias (46).

Additional evidence supporting a role for miR-1 in cardiac repolarization and arrhythmogenesis came from a rat model of myocardial infarction (MI) induced by occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery. An increase (approximately 2.6-fold) in miR-1 expression in the ischemic hearts was accompanied by exacerbated arrhythmogenesis. Elimination of miR-1 by an antisense inhibitor in the infarcted rat hearts relieved arrhythmogenesis. Overexpression of miR-1 resulted in slowed cardiac conduction, as indicated by the widening of QRS complex and measurement of cardiac velocity, and depolarizes the cytoplasmic membrane, which is likely the cellular mechanism for the arrhythmogenic potential of miR-1. MicroRNA-1 was found to target KCNJ2, which encodes the K+ channel subunit Kir2.1 (48). Kir2.1, which carries inward rectifier K+ current, is critical for setting and maintaining membrane potential. The resultant conduction slowing may be one mechanism for ventricular arrhythmias in the setting ischemia.

In contrast to ventricular arrhythmias, Girmatsion et al studied changes in miR-1 and Kir2 subunit expression in relation to IK1 alterations in the left atrial tissue samples from patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. IK1 density was increased in LA cells from patients with atrial fibrillation. There was a corresponding increase in Kir2.1 protein expression, but no change in other Kir protein levels. Expression of inhibitory miR-1 was reduced by approximately 86% in tissue samples of AF patients. Ex vivo tachy-stimulation of human atrial slices up-regulated Kir2.1 and down-regulated miR-1. The authors concluded that miR-1 levels are greatly reduced in human AF, possibly contributing to up-regulation of Kir2.1 subunits, thus leading to increased IK1 (49).

These studies together indicate that aberrant upregulation of miR-1 in ischemic myocardium contributes to arrhythmogenesis. The finding that an anti-miR-1 oligomer suppressed ischemic arrhythmias has implications as a potential therapeutic. An excessive decrease (as seen in the miR-1-2 knockout) or increase in miR-1 level can induce arrhythmia, which supports a central role for miR-1 for regulation of cardiac electrophysiology in pathological and normal conditions. Interestingly, in the setting of atrial fibrillation levels of miR-1 appear to be decreased in contrast to the increased miR-1 levels seen in ventricular arrhythmias (Table 1). To date, this differential regulation of miR-1 in atrial versus ventricular tissue has not been explored. Taken together, miR-1 levels within the myocardium must be kept within a proper concentration range to maintain normal cardiac conduction. Further study is warranted as this understanding could have profound implications for therapeutic applications.

Table 1.

MicroRNAs and identified targets in arrhythmia

| MicroRNA | Targets | Function |

|---|---|---|

| miR-1 | KCNJ2 | Decrease IK1 |

| GJA1 | Conduction slowing | |

| CACNA1C | Decrease ICaL | |

| Irx5 → KCND2 | Decrease Ito | |

| B56α → RyR2 | Altered Ca2+ cycling | |

| miR-133 | PP2A → RyR2 | Altered Ca2+ cycling |

| ? | Decreased Ito,f | |

| ERG | Decreased IKr | |

| miR-328 | CACNA1C, CACNB1 | Decrease ICaL |

| miR-212 | KCNJ2 | Decrease IK1 |

| miR-208a | GJA5 | Conduction slowing |

Like miR-1, miR-133 is a muscle-specific miRNA preferentially expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle. They represent the most abundant miRNAs expressed in the heart (50). In addition to miR-1, miR-133 has also been documented to be a miRNA regulator of cardiac ion channels. In a study by Matkovich et al, the authors described that increased miR-133a levels prolonged QT intervals in surface electrocardiographic recordings in mice and action potential duration in isolated ventricular myocytes, with a decrease in the fast component of the transient outward K+ current, Ito,f, at baseline (51). Interestingly, decreased mRNA and protein levels of Kv4-encoded Ito,f (Kcnip2) were observed; however, Kcnip2 has not been previously reported as a target of miR-133a and is not suggested to be an miR-133a target. The authors concluded that regulation of Kcnip2 transcript levels in miR-133a transgenic hearts occurred by an indirect mechanism not yet identified.

Arsenic trioxide (As2O3) has been shown to induce abnormal cardiac QT prolongation (52, 53). To study this, a guinea pig model of As2O3-induced QT prolongation was established by intravenous injection with As2O3. The QT interval and QRS complex were significantly prolonged in a dose-dependent fashion after 7-day administration of As2O3. Interestingly, As2O3 induced a significant up-regulation of the muscle-specific miR-1 and miR-133. As2O3 depressed the protein levels of ether-a-go-go related gene (ERG) and Kir2.1, the K+ channel subunits responsible for delayed rectifier K+ current IKr and inward rectifier K+ current IK1, respectively. In vivo transfer of miR-133 by direct intramuscular injection prolonged the QT interval and decreased the levels of ERG protein and IKr in guinea pig hearts. Similarly, forced expression of miR-1 increased the QT interval and QRS duration with a down-regulation of Kir2.1 protein and IK1. Delivery of antisense inhibitors to knockdown miR-1 and miR-133 abolished the cardiac electrical disorders caused by As2O3 (54).

MicroRNA-212 has been found to be upregulated in both animal models of heart failure as well as in human heart failure (55, 56). Bioinformatic analysis revealed a potential target in the 3′ UTR of Kir2.1 (KCNJ2) for miR-212. As mentioned previously, Kir2.1 carries an inward rectifier K+ current that is critical for setting and maintaining membrane potential and also a target for miR-1. Goldoni et al recently reported the targeting of Kir2.1 by miR-212 with functional down-regulation of inward rectifier K+ channels. Transfection of HeLa cells with a miR-212 overexpression construct reduced inward rectifier K+ current density, as demonstrated by whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, most likely due to reduced expression of Kir2.1 (57). The ability for miR-212 to result in cardiac arrhythmias was not studied in an animal model. However, miR-212 was found to be slightly up-regulated in patients with mitral stenosis and atrial fibrillation compared to those in sinus rhythm with mitral stenosis (58).

Regulation of Intercellular Conduction

Electrical activation of the heart requires transfer of current from one discrete cardiac myocyte to another, a process that occurs at gap junctions. Gap junction channels form the basis of intercellular communication in the heart. In the working myocardium, connexin43 (Cx43) is most abundantly found, whereas connexin40 (Cx40) is expressed in the atria and in the conduction system. Remodeling of gap junction organization and connexin expression is a common feature of human heart disease in which there is an arrhythmic tendency (61, 62). This remodeling may take the form of disturbances in the distribution of gap junctions and/or quantitative alterations in connexin expression, notably reduced ventricular connexin43 levels. In advanced stages of heart disease, connexin expression and intercellular coupling are diminished, and gap junction channels become redistributed. These changes have been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of lethal ventricular arrhythmias (63).

Several studies have highlighted the role of miR-1 in the regulation of Connexin43. In a mouse model of viral myocarditis, the expression levels of miR-1 and its target Connexin43 were measured by real-time PCR and western blotting, respectively. The miR-1 expression levels were significantly increased in cardiac myocytes from the viral myocarditis cohort compared to control. In cultured myocardial cells, overexpression of miR-1 via transfection accompanied resulted in a reduced levels of Cx43 protein with a non-significant drop in Cx43 mRNA levels (59). In the rat model of myocardial infarction discussed previously, miR-1 was found to regulate GJA1 in addition to KCNJ2 (48).

The multiplicity of miRNA targets allows miRNAs to target various mRNAs whose protein products contribute to several components of a pathway. In the study of myotonic dystrophy by Rao et al, the disrupted processing of pre-miR-1 resulted in the reduction of mature miR-1. In addition to CaV1.2, the expression of connexin43 was also upregulated in heart samples of affected individuals. These data demonstrated altered Dicer processing of miR-1 and the subsequent misregulation of miR-1 targets, CACNA1C and GJA1, likely contribute to the cardiac arrhythmias observed in affected persons.

Callis et al reported a role for miR-208a in regulation of connexin40 (64). MicroRNA-208a is encoded by an intron of the α-cardiac muscle myosin heavy chain gene (Myh6) and was initially found to regulate stress-dependent cardiac growth (65). The authors found miR-208a was required to maintain expression of cardiac transcription factors known to be important for development of the conduction system. In miR-208a knockout mice, approximately 80% developed an ECG consistent with atrial fibrillation. In the mice without atrial fibrillation, the PR intervals were significantly prolonged compared with wildtype animals. Overexpression of miR-208a was sufficient to induce prolonged PR intervals and occasional second-degree AV blocks suggesting that miR-208a regulates cardiac conduction system components. These results demonstrate the pathological consequences of perturbing the expression of a single miRNA in the heart and establish miR-208a as a regulator of hypertrophic growth and the cardiac conduction system (64).

Previous studies suggested that abnormal connexin protein expression might account for the cardiac conduction defects seen in the mouse models with altered miR-208a levels (66, 67). The authors evaluated the expression of Cx43 and Cx40 in hearts from 4-month-old miR-208a transgenic and miR-208a–/– mice. Though Cx40 mRNA transcript levels were not affected in miR-208a transgenic hearts, they were markedly decreased in miR-208a–/– hearts compared with wild-type, indicating that miR-208a is required for Cx40 expression. Western blot and immunohistological analyses of hearts from miR-208a–/– mice showed decreased Cx40 protein levels compared with wild-type hearts. Consistent with the miR-208a–/– phenotype, mice lacking Cx40 suffer cardiac conduction abnormalities, including first-degree AV block (66).

In the realm of therapeutics, inhibition of miR-208a has been investigated as a strategy to repress βMHC expression and remove some of the maladaptive features of hypertrophy. Given the findings of conduction abormalities in the miR-208a–/– mouse model, arrhythmogenesis induced by perturbing miR-208a levels warrants caution. To verify whether anti-miR-208a treatment resulted in cardiac conductance effects, Montgomery et al analyzed ECGs in both wild-type mice and diseased rats. Interestingly, both species showed proper cardiac electrophysiology after antimiR-208a treatment for an extended period of time (68).

Calcium cycling and arrhythmogenesis

Calcium enters cardiomyocytes via a variety of mechanisms, most prominent of which is the L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL). In a process commonly called Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release, voltage-dependent trans-sarcolemmal entry of Ca2+ triggers the release of additional Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores through closely coupled sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release channels. Ca2+ release channel function is regulated by key intracellular phosphorylating enzymes such as protein kinase A and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), as well as a variety of phosphatases, resulting in dephosphorylation. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content is dependant on several mechanisms such as cellular Ca2+ entry (particularly via ICaL), calcium removal from the cell (particularly via the sarcolemmal Ca2+ pump and forward-mode Na+-Ca2+ exchange) and Ca2+ pumping into the sarcoplasmic reticulum by the Ca2+-ATPase Ca2+ pump (the principal cardiac form of which is SERCA2a).

Heart failure has major effects on cellular Ca2+ handling, which has important implications not only for cardiac function but arrhythmogenesis as well. Triggered activity related to delayed afterdepolarizations (DAD) is caused by spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ release and is an important mechanism underlying ventricular tachyarrhythmias (69). Delayed afterdepolarizations occur in congestive heart failure despite reduced cell Ca2+ stores because of a number of features of cardiac failure-induced ion transport remodeling (70-72). First, hyperphosphorylated Ca2+ release channels are prone to spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ release. Second, for any given level of Ca2+ release, enhanced Na+-Ca2+ exchange function increases the depolarizing current resulting from electrogenic Ca2+ extrusion, with three Na+ transported into the cell for every Ca2+ ion transported out. Lastly, inward rectifier potassium current downregulation by elevated diastolic Ca2+ in heart failure might also be relevant for arrhythmia generation (73).

In hearts isolated from canines with chronic heart failure, qRT-PCR revealed that the levels of miR-1 and miR-133 were significantly increased in cardiomyocytes compared with controls. Western blot analyses demonstrated that expression levels of the protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) catalytic and regulatory subunits, putative targets of miR-133 and miR-1, were decreased in cardiomyocytes with chronic heart failure. PP2A catalytic subunit mRNAs were validated as targets of miR-133 by luciferase reporter assays. Pharmacological inhibition of phosphatase activity increased the frequency of diastolic Ca2+ waves and after-depolarizations in control myocytes. The decreased PP2A activity observed in heart failure was accompanied by enhanced Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKII)-mediated phosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor (RyR2) at sites Serine-2814 and Serine-2030 and increased frequency of diastolic Ca2+ waves and after-depolarizations in heart failure myocytes compared with controls. These findings suggest that altered levels of major muscle-specific miRNAs contribute to abnormal RyR2 function in chronic heart failure by depressing phosphatase activity localized to the channel, which in turn, leads to the excessive phosphorylation of RyR2s, abnormal Ca2+ cycling, and increased propensity to arrhythmogenesis (74).

Terentyev et al investigated the effects of increased expression of miR-1 on excitation-contraction coupling and Ca2+ cycling in rat ventricular myocytes. Adenoviral-mediated overexpression of miR-1 in myocytes resulted in a marked increase in the amplitude of the inward Ca2+ current, flattening of Ca2+ transients voltage dependence, and enhanced frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks while reducing the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content as compared with control. In the presence of isoproterenol, miR-1-overexpressing cardiomyocytes exhibited spontaneous arrhythmogenic oscillations of intracellular Ca2+ events. The effects of miR-1 were completely reversed by the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKII) inhibitor KN93. Although phosphorylation of phospholamban was not altered, miR-1 overexpression increased phosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor (RyR2) at Serine2814 (a target of CaMKII) but not at Serine2808 (a target for protein kinase A). Overexpression of miR-1 was accompanied by a selective decrease in expression of the protein phosphatase PP2A regulatory subunit B56α involved in PP2A targeting to specialized subcellular domains. These data demonstrated that miR-1 enhances cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by selectively increasing phosphorylation of the L-type and RyR2 channels via disrupting localization of PP2A activity to these channels (60).

MicroRNA misregulation in models of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained arrhythmia associated with substantial cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. As already discussed, target genes of miRNAs have the potential to influence AF through the effects on conduction properties. Structural remodeling, either through atrial dilatation or fibrosis also impacts the development of atrial arrhythmias. AF maintenance is importantly related to changes in atrial electrical and structural properties. Electrical remodeling occurs early during the course of AF and leads to characteristic changes in action potential shape and duration, whereas structural alterations develop more slowly. Atrial fibrillation, as a complex electrical phenotype involving complex factors beyond electrophysiology, can occur in a variety of pathological settings (63). Atrial fibrillation of different types has distinct underlying mechanisms, and different miRNAs may be involved in different types of atrial fibrillation (Table 2). Cooley et al examined miRNA expression profiles in right and left atrial appendage tissue from valvular heart disease patients. There was no detectable effect of chronic AF on miRNA expression in left atrial tissue, but miRNA expression in the right atrium was strongly influenced by AF, with forty-seven miRNAs showing differential expression between the AF and control sinus rhythm groups. Valvular heart disease induced different changes in miRNA expression in the left atrium compared with the right atrium. Fifty-three miRNAs were altered by the presence of valve disease in left atrium, compared with five in right atrial tissue.

Table 2.

| Arrhythmia/Conduction | Model | microRNA |

|---|---|---|

| Atrial Fibrillation | Tachy-paced canine | ↑ miR-328 |

| Tachy + nicotine | ↓ miR-133, miR-590 | |

| Human atrial tissue | ↓ miR-1, ↑ miR-21 | |

| Human atria+VD | ↑ miR-212 | |

| Transgenic mouse (Rac1) | ↑ miR-21 | |

| Mouse knockout | miR-208a KO | |

| QRS prolongation | Mouse knockout | miR-1-2 KO |

| As2O3 Guinea Pig | ↑ miR-1, ↑ miR-133 | |

| QT prolongation | Diabetic rabbit heart | ↑ miR-133 |

| αMHC transgenic (miR-133) | miR-133 TG | |

| As2O3 Guinea Pig | ↑ miR-1, ↑ miR-133 | |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia | Rat myocardial infarction | ↑ miR-1 |

| Human Myotonic Dystrophy | ↓ miR-1 | |

| Conduction Block | αMHC transgenic (miR-208a) | miR-208a TG |

| Human Myotonic Dystrophy | ↓ miR-1 |

In a study of patients with mitral stenosis and sinus rhythm or AF, miRNA arrays revealed that 136 miRNAs were differentially expressed in mitral stenosis patients with AF and 96 miRNAs were dysregulated in mitral stenosis patients without AF, compared with healthy controls. More importantly, 28 miRNAs were expressed differently in the MS patients with AF compared with the MS patients without AF (58). Taking these two studies together, the presence of valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation influences miRNA expression patterns in left atrium and right atrium (75). In addition, the differential miRNA expression between left and right atria in valve disease not only highlights the differences from one cardiac chamber to the next, but also the conditions in which the arrhythmia occurs.

Structural remodeling of the atrium is important for the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation but the underlying signal transduction is incompletely understood. Adam et al studied the role of microRNA-21 (miR-21) and its downstream target Sprouty 1 (Spry1) during atrial fibrillation and development of atrial fibrosis. Left atria from patients with AF showed a 2.5-fold increased expression of miR-21 compared to matched left atrium of patients in sinus rhythm. Increased miR-21 expression correlated positively with atrial collagen content and was associated with a reduced protein expression of Spry1 and increased expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), lysyl oxidase and Rac1-GTPase. Transgenic mice with cardiac overexpression of Rac1, which develop spontaneous AF and atrial fibrosis with increasing age, showed upregulation of miR-21 expression associated with reduced Spry1 expression. Inhibition of miR-21 by antagomir-21 prevented fibrosis of the atrial myocardium post-myocardial infarction (76).

As discussed previously, the development of interstitial fibrosis affects chamber geometry and the mechanical performance of the heart and thereby increases the likelihood of cardiac arrhythmias. Several studies have shown that nicotine abuse is associated with the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias and that nicotine accelerates atrial collagen accumulation (77-79). In a study by Shan et al, the authors utilized a canine model of AF by nicotine administration and rapid pacing. Administration of nicotine for 30 days increased AF vulnerability by approximately 8- to 15-fold in dogs. The role of microRNAs (miRNAs) on the expression and regulation of transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-β1), TGF-beta receptor type II (TGF-βRII), and collagen production was evaluated in vivo and in vitro. For in vitro studies, atrial fibroblasts isolated from healthy dogs were treated with nicotine. Nicotine stimulated remarkable collagen production and atrial fibrosis both in vitro in cultured canine atrial fibroblasts and in vivo in atrial tissues. Nicotine produced significant upregulation of expression of TGF-β1 and TGF-βRII at the protein level, and a 60-70% decrease in the levels of miRNAs miR-133 and miR-590. Luciferase reporter assays in HEK293 cells confirmed the ability of miR-133 to repress TGF-β1 expression and of miR-590 to repress TGF-βRII expression. To test the notion that miR-133 or miR-590 could cause suppression of collagen production in atrial fibroblasts, the authors transfected synthetic miR-133 or miR-590 into cultured canine atrial fibroblasts. They found that transfection of miR-133 or miR-590 into these fibroblasts decreased TGF-β1 and TGF-βRII levels and collagen content. These effects were abolished by the antisense oligonucleotides against miR-133 or miR-590. The authors concluded that the profibrotic response to nicotine in canine atrium was critically dependent upon downregulation of miR-133 and miR-590 (80). However, how nicotine results in this downregulation of these miRNAs remains unclear.

Conclusions

The available data from experimental studies demonstrate that miRNAs regulate numerous properties of cardiac excitability including conduction, repolarization, automaticity, Ca2+ handling, spatial heterogeneity, and apoptosis and fibrosis. MicroRNAs can also impose their regulatory actions on cardiac excitability indirectly through targeting non-ion channel genes, such as transcription factors, that in turn regulate expression of ion channel genes (Table 1). This mode of action reinforces the complex nature and fine-tuning regulation of miRNA actions. It must be noted that we have just begun to appreciate the role of miRNAs in controlling cardiac excitability and our understanding is still rather preliminary.

As the study of microRNAs begins to move into the arena of therapeutics, a thorough understanding of the broad functions of any particular miRNA is necessary to avoid unappreciated or even harmful “off target” effects. More importantly, although the role of miRNAs has started to be elucidated in the basis of individual entity as a part of the miRNA network, how these miRNAs integrate and interplay to regulate cardiac excitability is unknown. It is likely that multiple miRNAs contribute to controlling arrhythmogenicity of the heart and that different miRNAs are involved in different types of arrhythmias under different pathological conditions of the heart. Thus, it will be crucial to identify sets of miRNAs acting cooperatively within the cardiovascular system. This information will be particularly relevant to the development of miRNA-based therapeutics, as cocktails of miRNA inhibitors may prove more efficacious than targeting a single miRNA.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NIH K08-HL098565 and the Institute for Cardiovascular Research, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 3′UTR

3′ untranslated region

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- AP

action potential

- AV

atrioventricular

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase

- MI

myocardial infarction

- miRNA

microRNA

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- RyR2

ryanodine receptor

- SA

sinoatrial

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have read the journal’s policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No competing potential conflicts exist.

References

- 1.Marban E. Cardiac channelopathies. Nature. 2002 Jan 10;415(6868):213–8. doi: 10.1038/415213a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006 Aug 15;114(7):e257–354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janse MJ. Electrophysiological changes in heart failure and their relationship to arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2004 Feb 1;61(2):208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin CA, Matthews GD, Huang CL. Sudden cardiac death and inherited channelopathy: the basic electrophysiology of the myocyte and myocardium in ion channel disease. Heart. 2012 Apr;98(7):536–43. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003 Sep 25;425(6956):415–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Jin DY, McManus MT, Mourelatos Z. Precursor microRNA-programmed silencing complex assembly pathways in mammals. Mol Cell. 2012 May 25;46(4):507–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Feb;10(2):126–39. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004 Jan 23;116(2):281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004 Sep 16;431(7006):350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001 Oct 26;294(5543):853–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlesinger J, Schueler M, Grunert M, Fischer JJ, Zhang Q, Krueger T, et al. The cardiac transcription network modulated by Gata4, Mef2a, Nkx2.5, Srf, histone modifications, and microRNAs. PLoS Genet. 2011 Feb;7(2):e1001313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CY, Chen ST, Fuh CS, Juan HF, Huang HC. Coregulation of transcription factors and microRNAs in human transcriptional regulatory network. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(Suppl 1):S41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S1-S41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauersachs J, Thum T. Biogenesis and regulation of cardiovascular microRNAs. Circ Res. 2011 Jul 22;109(3):334–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boettger T, Braun T. A new level of complexity: the role of microRNAs in cardiovascular development. Circ Res. 2012 Mar 30;110(7):1000–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorn GW., 2nd MicroRNAs in cardiac disease. Transl Res. 2011 Apr;157(4):226–35. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elmen J, Lindow M, Schutz S, Lawrence M, Petri A, Obad S, et al. LNA-mediated microRNA silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2008 Apr 17;452(7189):896–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, Persson R, Lindow M, Munk ME, et al. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2010 Jan 8;327(5962):198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1178178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krutzfeldt J, Rajewsky N, Braich R, Rajeev KG, Tuschl T, Manoharan M, et al. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature. 2005 Dec 1;438(7068):685–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Rooij E, Olson EN. MicroRNA therapeutics for cardiovascular disease: opportunities and obstacles. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012 Nov;11(11):860–72. doi: 10.1038/nrd3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2007 Sep;4(9):721–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, et al. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007 May;13(5):613–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amin AS, Tan HL, Wilde AA. Cardiac ion channels in health and disease. Heart Rhythm. 2010 Jan;7(1):117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nerbonne JM, Kass RS. Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol Rev. 2005 Oct;85(4):1205–53. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangoni ME, Nargeot J. Genesis and regulation of the heart automaticity. Physiol Rev. 2008 Jul;88(3):919–82. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi W, Wymore R, Yu H, Wu J, Wymore RT, Pan Z, et al. Distribution and prevalence of hyperpolarization-activated cation channel (HCN) mRNA expression in cardiac tissues. Circ Res. 1999 Jul 9;85(1):e1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 2004 Apr;84(2):431–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campuzano O, Brugada R, Iglesias A. Genetics of Brugada syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010 May;25(3):210–5. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32833846ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maguy A, Le Bouter S, Comtois P, Chartier D, Villeneuve L, Wakili R, et al. Ion channel subunit expression changes in cardiac Purkinje fibers: a potential role in conduction abnormalities associated with congestive heart failure. Circ Res. 2009 May 8;104(9):1113–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bodi I, Mikala G, Koch SE, Akhter SA, Schwartz A. The L-type calcium channel in the heart: the beat goes on. J Clin Invest. 2005 Dec;115(12):3306–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI27167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klugbauer N, Welling A, Specht V, Seisenberger C, Hofmann F. L-type Ca2+ channels of the embryonic mouse heart. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002 Jul 5;447(2-3):279–84. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01850-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christel C, Cardona N, Mesirca P, Herrmann S, Hofmann F, Striessnig J, et al. Distinct localization and modulation of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels in mouse sinoatrial node. J Physiol. 2012 Oct 8; doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.239954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Q, Timofeyev V, Qiu H, Lu L, Li N, Singapuri A, et al. Expression and roles of Cav1.3 (alpha1D) L-type Ca(2)+ channel in atrioventricular node automaticity. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011 Jan;50(1):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ono K, Iijima T. Cardiac T-type Ca(2+) channels in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010 Jan;48(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goonasekera SA, Hammer K, Auger-Messier M, Bodi I, Chen X, Zhang H, et al. Decreased cardiac L-type Ca(2)(+) channel activity induces hypertrophy and heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012 Jan 3;122(1):280–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI58227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, Kumar P, Sachse FB, Beggs AH, et al. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Jun 7;102(23):8089–96. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102. discussion 6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs A, Knight BP, McDonald KT, Burke MC. Verapamil decreases ventricular tachyarrhythmias in a patient with Timothy syndrome (LQT8) Heart Rhythm. 2006 Aug;3(8):967–70. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sicouri S, Timothy KW, Zygmunt AC, Glass A, Goodrow RJ, Belardinelli L, et al. Cellular basis for the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestations of Timothy syndrome: effects of ranolazine. Heart Rhythm. 2007 May;4(5):638–47. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu Y, Zhang Y, Wang N, Pan Z, Gao X, Zhang F, et al. MicroRNA-328 contributes to adverse electrical remodeling in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2010 Dec 7;122(23):2378–87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.958967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groh WJ, Groh MR, Saha C, Kincaid JC, Simmons Z, Ciafaloni E, et al. Electrocardiographic abnormalities and sudden death in myotonic dystrophy type 1. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jun 19;358(25):2688–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charpentier F, Merot J, Loussouarn G, Baro I. Delayed rectifier K(+) currents and cardiac repolarization. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010 Jan;48(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva J, Rudy Y. Subunit interaction determines IKs participation in cardiac repolarization and repolarization reserve. Circulation. 2005 Sep 6;112(10):1384–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jost N, Virag L, Bitay M, Takacs J, Lengyel C, Biliczki P, et al. Restricting excessive cardiac action potential and QT prolongation: a vital role for IKs in human ventricular muscle. Circulation. 2005 Sep 6;112(10):1392–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.550111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu DW, Antzelevitch C. Characteristics of the delayed rectifier current (IKr and IKs) in canine ventricular epicardial, midmyocardial, and endocardial myocytes. A weaker IKs contributes to the longer action potential of the M cell. Circ Res. 1995 Mar;76(3):351–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramakers C, Stengl M, Spatjens RL, Moorman AF, Vos MA. Molecular and electrical characterization of the canine cardiac ventricular septum. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005 Jan;38(1):153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szentadrassy N, Banyasz T, Biro T, Szabo G, Toth BI, Magyar J, et al. Apico-basal inhomogeneity in distribution of ion channels in canine and human ventricular myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2005 Mar 1;65(4):851–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y, Ransom JF, Li A, Vedantham V, von Drehle M, Muth AN, et al. Dysregulation of cardiogenesis, cardiac conduction, and cell cycle in mice lacking miRNA-1-2. Cell. 2007 Apr 20;129(2):303–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Costantini DL, Arruda EP, Agarwal P, Kim KH, Zhu Y, Zhu W, et al. The homeodomain transcription factor Irx5 establishes the mouse cardiac ventricular repolarization gradient. Cell. 2005 Oct 21;123(2):347–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang B, Lin H, Xiao J, Lu Y, Luo X, Li B, et al. The muscle-specific microRNA miR-1 regulates cardiac arrhythmogenic potential by targeting GJA1 and KCNJ2. Nat Med. 2007 Apr;13(4):486–91. doi: 10.1038/nm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Girmatsion Z, Biliczki P, Bonauer A, Wimmer-Greinecker G, Scherer M, Moritz A, et al. Changes in microRNA-1 expression and IK1 up-regulation in human atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2009 Dec;6(12):1802–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002 Apr 30;12(9):735–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matkovich SJ, Wang W, Tu Y, Eschenbacher WH, Dorn LE, Condorelli G, et al. MicroRNA-133a protects against myocardial fibrosis and modulates electrical repolarization without affecting hypertrophy in pressure-overloaded adult hearts. Circ Res. 2010 Jan 8;106(1):166–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohnishi K, Yoshida H, Shigeno K, Nakamura S, Fujisawa S, Naito K, et al. Prolongation of the QT interval and ventricular tachycardia in patients treated with arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Dec 5;133(11):881–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-11-200012050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barbey JT, Pezzullo JC, Soignet SL. Effect of arsenic trioxide on QT interval in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Oct 1;21(19):3609–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shan H, Zhang Y, Cai B, Chen X, Fan Y, Yang L, et al. Upregulation of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 contributes to arsenic-induced cardiac electrical remodeling. Int J Cardiol. 2012 Aug 10; doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thum T, Galuppo P, Wolf C, Fiedler J, Kneitz S, van Laake LW, et al. MicroRNAs in the human heart: a clue to fetal gene reprogramming in heart failure. Circulation. 2007 Jul 17;116(3):258–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.687947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hou Y, Sun Y, Shan H, Li X, Zhang M, Zhou X, et al. Beta-adrenoceptor regulates miRNA expression in rat heart. Med Sci Monit. 2012 Aug 1;18(8):BR309–14. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldoni D, Yarham JM, McGahon MK, O’Connor A, Guduric-Fuchs J, Edgar K, et al. A novel dual-fluorescence strategy for functionally validating microRNA targets in 3-prime untranslated regions: regulation of the inward rectifier potassium channel Kir2.1 by miR-212. Biochem J. 2012 Aug 13; doi: 10.1042/BJ20120578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiao J, Liang D, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Zhang H, Li L, et al. MicroRNA expression signature in atrial fibrillation with mitral stenosis. Physiol Genomics. 2011 Jun 15;43(11):655–64. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00139.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu HF, Ding YJ, Shen YW, Xue AM, Xu HM, Luo CL, et al. MicroRNA-1 represses Cx43 expression in viral myocarditis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012 Mar;362(1-2):141–8. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terentyev D, Belevych AE, Terentyeva R, Martin MM, Malana GE, Kuhn DE, et al. miR-1 overexpression enhances Ca(2+) release and promotes cardiac arrhythmogenesis by targeting PP2A regulatory subunit B56alpha and causing CaMKII-dependent hyperphosphorylation of RyR2. Circ Res. 2009 Feb 27;104(4):514–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peters NS, Coromilas J, Severs NJ, Wit AL. Disturbed connexin43 gap junction distribution correlates with the location of reentrant circuits in the epicardial border zone of healing canine infarcts that cause ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1997 Feb 18;95(4):988–96. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao JA, Hussain W, Patel P, Peters NS, Boyden PA, Wit AL. Remodeling of gap junctional channel function in epicardial border zone of healing canine infarcts. Circ Res. 2003 Mar 7;92(4):437–43. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000059301.81035.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nattel S, Maguy A, Le Bouter S, Yeh YH. Arrhythmogenic ion-channel remodeling in the heart: heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation. Physiol Rev. 2007 Apr;87(2):425–56. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Callis TE, Pandya K, Seok HY, Tang RH, Tatsuguchi M, Huang ZP, et al. MicroRNA-208a is a regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and conduction in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009 Sep;119(9):2772–86. doi: 10.1172/JCI36154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill J, Olson EN. Control of stress-dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science. 2007 Apr 27;316(5824):575–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1139089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simon AM, Goodenough DA, Paul DL. Mice lacking connexin40 have cardiac conduction abnormalities characteristic of atrioventricular block and bundle branch block. Curr Biol. 1998 Feb 26;8(5):295–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lo CW. Role of gap junctions in cardiac conduction and development: insights from the connexin knockout mice. Circ Res. 2000 Sep 1;87(5):346–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Montgomery RL, Hullinger TG, Semus HM, Dickinson BA, Seto AG, Lynch JM, et al. Therapeutic inhibition of miR-208a improves cardiac function and survival during heart failure. Circulation. 2011 Oct 4;124(14):1537–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001 Jun 8;88(11):1159–67. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res. 2005 Dec 9;97(12):1314–22. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pogwizd SM, Bers DM. Cellular basis of triggered arrhythmias in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004 Feb;14(2):61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fozzard HA. Afterdepolarizations and triggered activity. Basic Res Cardiol. 1992;87(Suppl 2):105–13. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72477-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fauconnier J, Lacampagne A, Rauzier JM, Vassort G, Richard S. Ca2+- dependent reduction of IK1 in rat ventricular cells: a novel paradigm for arrhythmia in heart failure? Cardiovasc Res. 2005 Nov 1;68(2):204–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Belevych AE, Sansom SE, Terentyeva R, Ho HT, Nishijima Y, Martin MM, et al. MicroRNA-1 and -133 increase arrhythmogenesis in heart failure by dissociating phosphatase activity from RyR2 complex. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cooley N, Cowley MJ, Lin RC, Marasco S, Wong C, Kaye DM, et al. Influence of atrial fibrillation on microRNA expression profiles in left and right atria from patients with valvular heart disease. Physiol Genomics. 2012 Feb 13;44(3):211–9. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00111.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adam O, Lohfelm B, Thum T, Gupta SK, Puhl SL, Schafers HJ, et al. Role of miR-21 in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrosis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012 Sep;107(5):278. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goette A, Lendeckel U, Kuchenbecker A, Bukowska A, Peters B, Klein HU, et al. Cigarette smoking induces atrial fibrosis in humans via nicotine. Heart. 2007 Sep;93(9):1056–63. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.087171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yashima M, Ohara T, Cao JM, Kim YH, Fishbein MC, Mandel WJ, et al. Nicotine increases ventricular vulnerability to fibrillation in hearts with healed myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000 Jun;278(6):H2124–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benowitz NL, Gourlay SG. Cardiovascular toxicity of nicotine: implications for nicotine replacement therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Jun;29(7):1422–31. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shan H, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Pan Z, Cai B, Wang N, et al. Downregulation of miR-133 and miR-590 contributes to nicotine-induced atrial remodelling in canines. Cardiovasc Res. 2009 Aug 1;83(3):465–72. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]