Abstract

Introduction

Racial and ethnic minorities have disproportionately higher cancer incidence and mortality than their White counterparts. In response to this inequity in cancer prevention and care, community-based lay health advisors (LHAs) may be suited to deliver effective, culturally relevant, quality cancer education, prevention/screening, and early detection services for underserved populations.

Approach and Strategies

Consistent with key tenets of community-based participatory research (CBPR), this project engaged community partners to develop and implement a unique LHA training curriculum to address cancer health disparities among medically underserved communities in a tricounty area. Seven phases of curriculum development went into designing a final seven-module LHA curriculum. In keeping with principles of CBPR and community engagement, academic–community partners and LHAs themselves were involved at all phases to ensure the needs of academic and community partners were mutually addressed in development and implementation of the LHA program.

Discussion and Conclusions

Community-based LHA programs for outreach, education, and promotion of cancer screening and early detection, are ideal for addressing cancer health disparities in access and quality care. When community-based LHAs are appropriately recruited, trained, and located in communities, they provide unique opportunities to link, bridge, and facilitate quality cancer education, services, and research.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, lay health workers, community health workers, community health advisors, training curriculum

INTRODUCTION

Cancer health disparities are well documented across the continuum of disease and care spectrum with most communities of color having significantly higher incidence and mortality rates from cancer than Whites—despite advances in risk factor management, screening, early detection, and treatment campaigns (American Cancer Society, 2009a, 2009b, 2011; Harper & Lynch 2005; Institute of Medicine, 2002; Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). A factor that contributes to the aforementioned inequality is the persistent lack of accessible, affordable, and culturally relevant programs for cancer prevention and control among medically underserved and historically marginalized racial–ethnic minority communities. To improve access to quality care, community-based lay health advisors (community health workers, promotoras, lay health promoters, community health advisors) may serve an important role as a culturally relevant and effective workforce in community-based programs aimed at improving prevention, early detection, and cancer control in underserved communities (Cherrington, Ayala, Amick, Scarinci, et al., 2008; Cherrington et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2010; O’Brien, Halbert, Bixby, Pimentel, & Shea, 2010; Wadler, Judge, Prout, Allen, & Geller, 2011; Wells et al., 2011). Community-based lay health advisors (LHAs) are generally considered to be trusted indigenous aides or natural helpers who know the communities of interest and are culturally credible leaders who can be trained to educate, facilitate, navigate, and assist community members in accessing resources for critical chronic disease prevention, control, and health promotion.

In 2005, The National Workforce Study estimated that there were approximately 121,000 community health workers (CHWs) in the country (Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], 2007; Wells et al., 2011s), with an estimated 5,000 in Florida (Collins Center for Public Policy, 2011). More recently, there has been an emphasis on employing CHWs to improve racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare (Smedley et al., 2003) and some studies recognize the positive impact of CHWs in the United States (HRSA, 2007; Wells et al., 2011). In 2011, following the lead of several other states, Florida began an initiative to develop and promote the work of CHWs (Collins Center for Public Policy, 2011).

Roles, Functions, and Impact of Lay Health Advisors

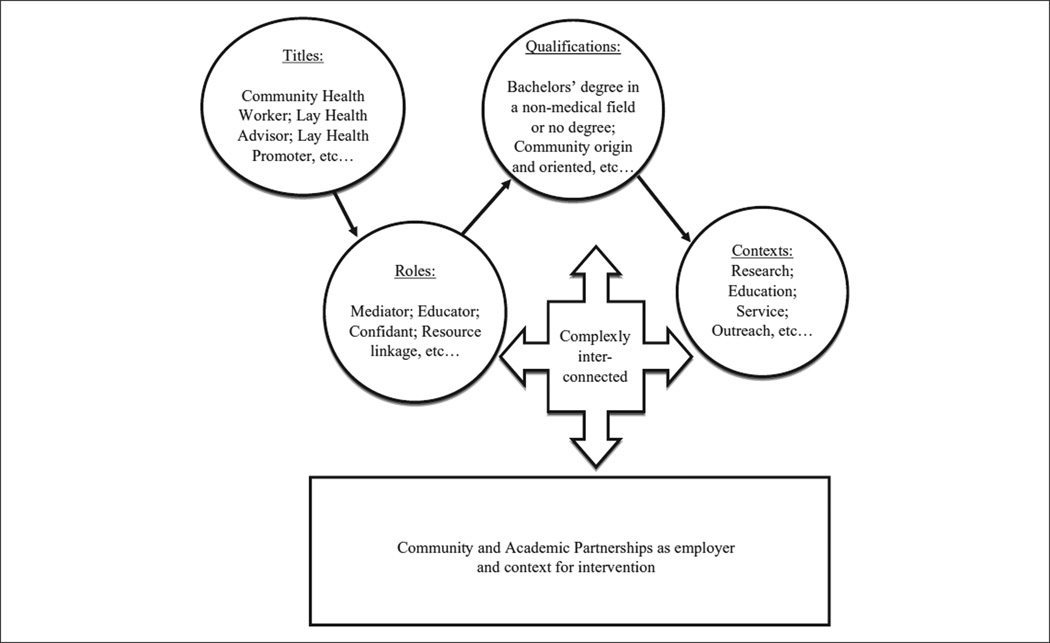

The role of LHAs in reducing disparities by linking members of hard-to-reach communities with health care providers and services has been highlighted by numerous studies showing effectiveness of LHAs in prevention and management of many chronic diseases (Cherrington, Ayala, Amick, Allison, et al., 2008; Cherrington et al., 2010; Kuhajda et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2010; Wadler et al., 2011; Wells at al., 2011). Use of LHAs holds great promise for enhancing the cultural, linguistic and literacy relevance of community-based outreach, education, and prevention programs; however, an inherent challenge and source of confusion is that LHAs have different names, roles, qualifications, and training differs across programs and settings (Cherrington et al., 2010; Hill-Briggs et al., 2007; O’Brien, Squires, Bixby, & Larson, 2009). Despite these challenges, seven core roles have been identified, according to the National Community Health Advisor Study (Rosenthal, 1998). These roles include

proving cultural mediation between communities and health and human service systems,

providing informal counseling and social support,

providing culturally appropriate health education,

advocating for individual and community needs,

ensuring that people obtain necessary services,

building individual and community capacity, and

providing basic access to screening services.

Diversity in LHA roles, qualifications, and practice settings makes it difficult to compare and evaluate the collective effects of this intuitively beneficial approach. One distinction in LHA roles and functionality is whether they are employed in the context of a research project or solely as community outreach practitioners; the scope and fidelity of implementation may vary in intensity and process documentation and measured outcomes depend on employment setting or context. In a dual employment role, the question is how to balance the seemingly mutually exclusive roles of LHAs as research partners or interventionists, versus their programmatic outreach and education practitioners. Another distinction is the varied employment categories ranging from volunteers, to paid part-time staff, to paid full-time staff in benefited positions and whether LHAs are employees of academic institution or community-based organization. In addition, the ever present challenges regarding balance of power and equitable resource sharing among academic and community entities must be attended with forthright transparency for such community–academic collaborations to succeed. As such, these and other prevailing challenges are further compounded in the current environment of limited funding and employment opportunities.

Proposed Role of Lay Health Advisors in Center for Equal Health

The Center for Equal Health (CEH), a National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Exploratory Center of Excellence, is a collaborative, transdisciplinary partnership between the University of South Florida, Moffitt Cancer Center, and the Tampa Bay community (Green et al., 2012). The CEH’s goals include addressing and reducing cancer health disparities within minority and underserved populations in the Tampa Bay community. In the Community Engagement and Outreach Core (CEOC) of the CEH, we view the use of community-based LHAs as a feasible and effective strategy for delivery of cancer education interventions and linkage of underserved community members to cancer prevention and control services (Green et al., 2012). The LHA facilitates the dissemination of cancer prevention, education, and research information, serves to connect community members with resources, is an essential behavior modification and research change agent, and strengthens linkages between communities, academic researchers, and providers, as well as community-based health providers (see Figure 1; Cherrington et al., 2010; Hill-Briggs et al., 2007; O’Brien et al., 2009). The LHAs are based in our communities within our community partners, but are employed by the CEH to improve their integration, increase access to institutional resources and maximize their day-to-day engagement in processes and decision making about outreach activities.

Figure 1.

Many Names, Diverse Roles, Qualifications, Contexts, and Relationships

Purpose of This Article

This article describes the initial development and implementation of a general LHA cancer health disparities training curriculum (including subsequent training of LHAs and evaluation of the training). The article covers three specific activities of the LHA training: (1) development of a cancer health disparities LHA curriculum, (2) recruitment and hiring of LHAs matching the populations/communities of interest, and (3) training of LHAs and evaluation of the training program. The challenges and lessons learned in recruitment, curriculum development and training are discussed with the goal of informing future community-based participatory cancer health disparities initiatives using the LHA approach in the broad context—beyond the realm of a specific research project or a single targeted cancer site. We expect the process of developing the LHA curriculum will aid other organizations hoping to use LHAs in their own programs.

APPROACH, STRATEGIES, AND RESULTS

Geographic Area, Populations, and Community Engagement

The geographic areas and populations of interest at CEH include selected medically underserved areas in three neighboring counties, Hillsborough, Pasco, and Pinellas, in close proximity to the University of South Florida and the Moffitt Cancer Center. For our purposes, medically underserved populations include primarily individuals and families who are uninsured and underinsured, and those with limited literacy and proficiency in the English language. A growing number of these populations include recent immigrants from non-English speaking Caribbean, and Central and South American countries. Consistent with key tenets of communitybased participatory research (CBPR; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008) and community action participation (Freire, 1970), community members are involved in the leadership of the CEOC or as part of the center-wide community-advisory group, thus ensuring a heightened focus on community benefit from cancer education, outreach and research. In addition, LHAs who share the demographic characteristics of the primary communities served by the CEH were trained. In total, seven LHAs attended trainings: two males and five females, two bilingual English–Spanish, two bilingual English–Haitian Creole, six self-identified as Black/ African American, and one as Hispanic/Latino.

Lay Health Advisor Curriculum Development

We developed a unique LHA training curriculum based on the CEH’s goals, the needs of local communities, and LHAs core roles being used across the United States (Rosenthal, 1998). Guided by the principles of CBPR and community engagement (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Salber, 1979), CEH staff and faculty, community partners, and hired LHAs collaborated through seven phases of curriculum development that ultimately resulted in a final seven-module LHA curriculum. Specifically, at least two community partners (co-leaders) and available LHAs were involved throughout the seven phases of the planning, development, and implementation process to ensure community participation in decisions. The phases and ultimate seven topical areas (modules) are described below.

Phase 1: Defining the needs of the partnership between CEH and the community

To correctly develop a meaningful and beneficial curriculum for LHAs, it was important to identify the needs of community partners and the CEH. The community was in need of cancer health information addressing both men and women, with a focus on health disparities in cancer, research, and clinical trials. The CEH needed the community to understand the purpose of research and participation in research, specifically behavioral and clinical trials. Hence both perspectives were continually considered throughout the planning and implementation of the LHA program. Existing community needs assessment reports and new input from community partner organizations was integrated in the process of consolidating the common vision on how the LHA program would benefit the CEH and the community.

Phase 2: Designing goals and objectives of an LHA program for the CEH

After determining the needs of community partners and the CEH, the goals and objectives for the LHA program were designed. The established primary goal of the LHA program is to reduce cancer health disparities. This is to be accomplished by aiding community members to utilize area resources, to increase community knowledge of health disparities, cancer, research, and clinical trials, and to provide a safe and trusted environment for community members to learn about these sensitive issues, discuss them, and find local resources.

Phase 3: Understanding the roles of LHAs in the CEH

The varying roles of an LHA are confusing to organizations and community members (Rosenthal, 1998). For this reason, it was important to establish the qualifications of LHAs and the expected roles that the CEH’s LHAs would fulfill. Short-term roles include (1) a basic lay educator, to increase community awareness about cancer disparities using preexisting educational materials; (2) an education facilitator, leading “Talking Circles,” small discussion-based groups that use specific talking points about cancer to educate community members; (3) being a guide to find resources and help community members access them; and (4) being the face of the community within the CEH and the face of CEH within the community. Long-term roles include (1) being an educator, leading education and awareness about cancer, health disparities, research, and clinical trials in the community and (2) being a spokesperson, helping the community learn the benefits from improved access to cancer education and screening resources, becoming informed about potential risks and questions to ask before participating in clinical trials, and the potential individual and community benefits from participating in research.

Phase 4: Necessary skills

Four skills were identified to be essential to a successful LHA program: (1) understanding their roles (listed above) and how to work within the boundaries of those roles; (2) communication skills; (3) skills for working in the community; and (4) knowledge about cancer, health disparities, research, and clinical trials. The LHA curriculum included emphasis on both technical skills of delivering cancer education as well as interpersonal and communicative skills to build rapport with community members and maintain long-term trusting relationships with communities.

Phase 5: Designing the curriculum

We determined that developing the necessary skills (described above) would be the focus of the curriculum. Seven modules were designed to encompass these necessary skills (see Table 1). Experienced faculty members, graduate students, LHAs, and community co-leaders created the modules, which included a workbook with information, vignettes, and activities to guide the training sessions. The seven content areas of the curriculum included the following: (1) LHA Roles and Duties, (2) Communication Skills, (3) Working in the Community, (4) Health Disparities, (5) Cancer 101, (6) Research 101, and (7) Clinical Trials and the Community (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Lay Health Advisor (LHA) Curriculum Components and Implementation Schedule

| Module No. and Title | Session No. and Date |

Content Area | Goals | Enhancements as a Result of LHA/Community Member Input |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Role/duties of a LHA | Session 1: April 15, 2010 |

Expectations and responsibilities of a lay health worker |

To understand what lay health advisors are and what they do |

Set boundaries on roles of LHAs in the context of outreach (not research roles) |

| 2: Communication | Session 1: April 15, 2010 |

Effective communication |

To explore ways to deliver accurate and appropriate health information that can contribute to the community’s health and overall well-being |

Identified evidence-based, easy-to-navigate sources (such the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention websites) as resources for LHAs in addition to their program specific workbook with appropriate resource materials such as brochures, videos, articles, etc |

| 3: Working in the community |

Session 1: April 15, 2010 |

Community-based participatory research |

Define community and perspectives that affect LHA activities. Discuss frameworks for reaching individuals and groups in the community |

LHAs and community partners reiterated that community is an asset (and has resources) not just a recipient. Thus all trainings were held at community partner facilities. Community also identified “nontraditional” venues for outreach |

| 4: Health disparities | Session 2: June 10, 2010 |

Social determinants of health and issues in health disparities |

Understand what health disparities are and which ones affect your community |

Cancer health disparities are not the priority day-to-day area of need. As such, community encouraged more partnerships with other organizations dealing with general health and other social problems most salient to medically underserved populations in addition to cancer |

| 5: Cancer 101 | Session 2: June 10, 2010 |

An introduction to general cancers |

Understand what cancer is, the basic causes, and be able to relay that info to the community |

LHA input led to language simplification for each module, particularly the last three. The advisory board for one of the community partners offered feedback on which cancer sites to target in our initial outreach efforts, that is, prostate, colon cancer and breast cancer. Also community partners emphasized need for the academic partners to provide more resources for follow-up care for abnormal screening or if cancer is found for uninsured and underinsured |

| 6: Research 101 | Session 3: October 24, 2010 |

Research and research methods |

Understand the importance and methods of basic research |

LHAs wanted to teach community members early on in life about importance of all research: behavioral, clinical, or community |

| 7: Clinical trials | Session 4: March 22, 2011 |

Clinical trials | Identify what a clinical trial is, how they work, and why are they necessary |

This module also generated much interest given the documented challenges with minority participation in research. Community partners welcomed the idea of educating the general public about research to increase their readiness to participate in clinical trials in the future if they ever became eligible |

NOTE: A common and cross-cutting feedback by LHA and community members was the need to simplify the curriculum and make the curriculum more user-friendly. This resulted in a workbook format with all modules consisting of four components:

1. core content presented in outline format with bullets, diagrams, and resource lists;

2. PowerPoint slide deck adaptable for use by LHAs in conducting “Talking Circles” or individual or group education at Health Fairs;

3. exercises/vignettes and worksheets; and

4. video clips (where available).

Phase 6: Piloting the training

After completing the information within each module, pilot trainings were held with the community partners and already hired LHAs. Feedback from these sessions is discussed further below.

Phase 7: Next steps

Using the feedback from our pilot trainings, changes were made to the modules. Currently, a top priority is to put all of the modules together into a user-friendly format that facilitates the training for both the trainers and the audience (LHAs). This includes modifications to the workbooks and the PowerPoint slides, changing the aesthetics by creating pleasing layouts, designs, and creating a sense of uniformity across all modules. The final steps include copy writing the final product and disseminating our efforts to communities as needed; it is noted that further adaptations may be necessary for tailoring to each community or culture group. In addition, an extension in the training curriculum is underway to provide cancer site specific training and resources for the LHAs to lead “Talking Circles” or individual education at health fairs on several cancer specific topics, including but not limited to, breast, prostate, and colon cancer.

Recruitment of and Training of Lay Health Advisors

After review of the literature (Cherrington et al., 2010; O’Brien et al., 2009), a model using paid LHAs (rather than unpaid volunteers) was implemented. Three parttime positions (20 hours per week without benefits), one per county were approved. The LHAs were hired by the CEH and deployed in the community to work with community partner organizations. Community partners and CEH staff collaboratively created the job descriptions and recruitment materials. The position announcements were distributed by email, newsletters, CEH newsletter, university publications, community-based newsletters and newspapers, and handed to community members for word of mouth referrals. The CEOC coordinator and CEOC core leaders (academic faculty investigators and community co-leaders) collaboratively recruited and hired the LHAs.

Lay Health Advisor Training and Evaluation

Subsequent to the design of the LHA training modules, the initial training was held in four separate sessions (see Table 1) and thereafter it was implemented on a rolling basis as new personnel were hired. The modules were administered interactively with PowerPoint slides, worksheets/exercises with vignettes, and question and answer session or role play as indicated. Each module was presented by a faculty member with expertise on the topic plus a graduate student, a community co-leader, and the CEOC coordinator—all of whom were involved in development of the specific modules. In addition, most modules were video- or audio-taped for future reference and to help standardize the training. To evaluate the success of each curriculum component (module) and project efficacy in the community, anonymous qualitative and quantitative items were administered at the end of each session. Each module was administered over an average of 2 hours; thus the length of each session varied depending on the number of modules included in the session. The number of LHAs attending each initial pilot session varied from two to five. The results of the implementation of each session are summarized below.

Session 1: Modules 1 to 3—Duties of an LHA, communication, and working in the community

A total of 7 persons participated in the training and evaluation process, including 3 LHAs, 1 community partner, and 3 CEH staff members. Overall, 71% of participants indicated that they were “comfortable” with the components of Module 1, Duties of a Lay Health Advisor. Similarly, 86% of participants reported being either “comfortable” or “very comfortable” with the components of Modules 2 and 3, Communication and Working in the Community, respectively. Regarding overall effectiveness, 100% of participants reported being either “very satisfied” (57%) or “satisfied” (43%) with the first Lay Health Advisor Curriculum Training Session. A sampling of results is summarized in Table 2 for illustration purposes. In addition, responses to an openended question were positive as summarized in the following representative statement. When asked “What are your concerns about implementing the training content or material?” one participant responded with the following:

This was my first health training, and I received lots of great information that I could take back and share with my fellow school mates and others in my community. It also raised awareness for me because I have children and our health is very important to me. So I have learned different approaches to speak with doctors about our health concerns.

TABLE 2.

Summary Example of Evaluation Data Regarding Satisfaction and Comfort Level With Curriculum Training Session or Components

| Question | Category | Percentage (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Please rate your overall satisfaction with components of the Lay Health Advisor Curriculum Training Session |

Very satisfied | 57.1 (4) |

| Satisfied | 42.9 (3) | |

| Please rate your comfort level with each of the following components of training session: | ||

| Role of lay health advisors | Very comfortable | 28.6 (2) |

| Comfortable | 71.4 (5) | |

| Psychosocial communication | Very comfortable | 14.3 (1) |

| Comfortable | 71.4 (5) | |

| Neutral | 14.3 (1) | |

| Working in the community | Very comfortable | 14.3 (1) |

| Comfortable | 85.7 (6) | |

Session 2: Module 4—Health disparities and Module 5—Cancer 101

These modules involved a total of 10 participants, including 2 LHAs, 2 community members, and 6 CEH/CEOC faculty and staff members. On completion of Module 4, 91% of participants selfreported to be satisfied with their increased understanding of the topic. Regarding Cancer 101, 100% of participants reported that they will be able to apply the knowledge learned. Overall, 72% of participants reported that the Health Disparities module met their expectations; 91% said that the Cancer 101 module met their expectations. In addition, responses to an open-ended question were positive as summarized below. When asked “What aspects of the training were your favorites?” one participant responded with the following:

The videos and discussions afterwards were particularly stimulating and helpful. Also, I thought the handouts were well put together and contained useful information. The mini-test at the beginning was an eye-opener and should be used in the future. Maybe have participants take the same one again (a posttest) at the next meeting.

Session 3: Module 6—Research 101

This module had 7 participants, including 3 LHAs, 1 community partner, and 3 graduate students or CEH. On completion of the Research 101 training module, 67% of participants “strongly [agreed]” that they understood “the basic components of a research design, including the protocol, research question, methodology, and evaluation of the data.” Regarding overall effectiveness, 89% of participants rated the overall Research 101 training as “excellent.” In addition, responses to an open-ended question were positive as summarized below. When asked “What aspects of the training could be improved?” one participant responded with the following:

Graphics, formatting, etc. of manuals (minor changes, not major).

Session 4: Module 7—Clinical trials

This module had 13 participants, including 5 LHAs, 2 community members, and 6 CEH/CEOC faculty and staff members. Results indicate that on completion of the Clinical Trials module, 92% of participants answered “strongly agree” when asked if they understood the risks and benefits of a clinical trial. Overall, 62% of patrons rated the effectiveness of the clinical training as “excellent,” and 15% rated the training as “good.” In addition, qualitative sentiments about the training can be gleaned from the following response. When asked for additional comments, one participant responded with the following:

I had some understanding of clinical trials, but this workshop made the definitions more scientific. This was very helpful with knowing the process of clinical trials.

After completion of initial general training, LHAs received further training in the field under the supervision of the community co-leaders and the CEOC coordinator to improve the LHAs’ comfort levels and provide additional hands-on training and evaluation of their skills.

DISCUSSION

Few studies have reported on LHA curriculum development, training, and evaluation for addressing cancer health disparities. This article fills a clear gap identified in a recent systematic review suggesting that few studies have documented use of CBPR approach in the development of LHA curriculum and selection of LHAs (O’Brien et al., 2009). In addition, this article details content of general LHA training and the time needed to complete initial training. Given the complexity of cancer and health disparities as topics, we used a two-stage approach—separated the general skills training from the disease (cancer type) targeted training— consistent with observations reported by O’Brien et al. (2009). As such, this article may assist other cancer health disparities researchers who may wish to replicate or adapt our experiences. Furthermore, we discuss lessons learned: development of a LHA training curriculum, use of CBPR and equitable participation of community in decision making and resource sharing, stepped approach to general and disease specific training, importance of paid LHA positions versus volunteers, and future directions.

The value of the CBPR approach and community partner participation in decision making at all steps of the training process is apparent in the selection of curriculum modules, improvements to the curriculum and the pragmatic feedback that was received. Community partner feedback and evaluation of LHAs training infused nuances of culture and literacy components that improved the salience and usability of the curriculum. Moreover, with feedback of community partners, community members and LHAs, we adopted a stepped approach which called for implementing the general curriculum first and later conduct training on the cancer site specific modules (which had already been developed by a local organization). This improved feasibility and comfort level of LHAs, and reduced feelings of being overwhelmed about learning all these skills at once.

Despite the small number of LHAs trained, our experiences with the development of cancer health disparities training for LHAs in CEH are both unique and complementary to the few programs documented in the literature (O’Brien et al., 2009; Reinschmidt & Chong, 2007; Yu et al., 2007). Although most LHAs employed for cancer-specific initiatives have been used in the setting of specific research projects (Wells et al., 2011; typically focusing on one cancer site), our LHAs were primarily intended for general cancer health disparities outreach, education, and facilitation of screening access where indicated. In this regard, our LHAs had to muster a broad set of skills as well as disease specific knowledge in the different cancer sites. However, our results do compare to and parallel the lessons and challenges in the literature. These include the common challenges of role delineation, determining which role (volunteer, part time, or full time) is best suited for the project, and effectively recruiting and hiring individuals who are vested in working in their communities (HRSA, 2007; O’Brien et al., 2009). Despite the obvious positive benefits, there remain many challenges to the “standardization and professionalization” of LHA training curricular and their work. For example, a standardized (one size fits all) curriculum may not be practical for all communities; some adaptation or tailoring is often needed for specific communities. Second, with the increased professionalization of a workforce comes the challenges of ensuring employment opportunities, need for centralized resources for developing and implementing certification and monitoring standards. Another local challenge faced by programs is how to define the scope of activity with regards to both the geographic scope to be covered and racial/ethnic-matching of LHAs to the population demographics. In the case of CEH, with three counties to be covered and diverse communities (race, ethnicity, language, and rural/urban, etc.) within and between counties, these issues remain ongoing challenges for our program. As a future direction for sustainability, in addition to the need for sufficient financial resources, there is need to explore the utility of career ladder and use of the “train-the-trainer” model to help disseminate effective programs. To achieve the latter, the current pilot LHA curriculum will be adapted by the CEH LHAs to offer training for volunteer LHAs or other LHAs employed at community-based organizations. The Florida CHW state-wide initiative is likely to aid with standardization and sustainability (Collins Center for Public Policy, 2011).

CONCLUSIONS

Community-based LHA programs for outreach, education, and promotion of cancer screening and early detection, have high potential for addressing cancer health disparities in access and quality of care. When community-based LHAs are appropriately recruited, trained, and deployed, they provide unique opportunities to link, bridge, and facilitate quality cancer education, services, and research to reduce cancer disparities. Concerted efforts are needed to train a large number of LHAs and implement larger scale practitioner LHA programs before the full benefits of community-based LHAs are realized locally and nationally. The lessons learned from CEH–CEOC are informative to other similar regional or national initiatives. Finally, the critical benefits and cross-cutting cultural and linguistic contributions of community-based LHAs cannot be assured when LHAs are not carefully identified/recruited, hired, trained, and deployed in ways that leverage these salient qualities.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number P20MD003375 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2009–2010. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2009a. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2009–2011. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2009a. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2011. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cherrington A, Ayala GX, Amick H, Allison J, Corbie-Smith G, Scarinci I. Implementing the community health worker model within diabetes management: Challenges and lessons learned from programs across the United States. The Diabetes Educator. 2008;34:824–833. doi: 10.1177/0145721708323643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrington A, Ayala GX, Amick H, Scarinci I, Allison J, Corbie-Smith G. Applying the community health worker model to diabetes management: Using mixed methods to assess implementation and effectiveness. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2008;19:1044–1059. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrington A, Ayala GX, Elder JP, Arredondo EM, Fouad M, Scarinci I. Recognizing the diverse roles of community health workers in the elimination of health disparities: From paid staff to volunteers. Ethnicity & Disease. 2010;20:189–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Center for Public Policy. Community health workers in the U.S. in Florida: Reducing costs, improving health outcomes and creating a pathway to work. Miami, FL: Author; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.floridachwn.cop.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/CHWPolicyBriefFINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Rivers DA, Kumar N, Baldwin J, Rivers BM, Sultan D, Roetzheim R. Establishing the infrastructure to comprehensively address cancer disparities: A model for transdisciplinary approaches (Manuscript submitted for publication) 2012 doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Harper S, Lynch J. Methods for measuring cancer disparities: Using data relevant to healthy people 2010 cancer related objectives (NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series No. 6) Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Community Health Worker National Workforce Study. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Briggs F, Batts-Turner M, Gary TL, Brancati FL, Hill M, Levine DM, Bone L. Training community health workers as diabetes educators for urban African Americans: Value added using participatory methods. Progress in Community Health Partnership. 2007;1:185–194. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhajda MC, Cornell CE, Brownstein JN, Littleton MA, Stalker VG, Bittner VA, Raczynski JM. Training community health workers to reduce health disparities in Alabama’s black belt: The Pine Apple Heart Disease and Stroke Project. Family & Community Health. 2006;29:89–102. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community-based participatory research for health. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TT, Love MB, Liang C, Fung LC, Nguyen T, Wong C, Woo K. A pilot study of lay health worker outreach and colorectal cancer screening among Chinese Americans. Journal of Cancer Education. 2010;25:405–412. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0064-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MJ, Halbert CH, Bixby R, Pimentel S, Shea JA. Community health worker intervention to decrease cervical cancer disparities in Hispanic women. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:1186–1192. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MJ, Squires AP, Bixby RA, Larson SC. Role development of community health workers: An examination of selection and training processes in the intervention literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(6 Suppl. 1):S262–S269. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinschmidt KM, Chong J. SONRISA: A curriculum toolbox for promotores to address mental health and diabetes. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4:A101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal EL. Summary of the National Community Health Advisor Study. Weaving the Future. 1998 Jun; Retrieved from http://crh.arizona.edu/sites/crh.arizona.edu/files/pdf/publications/CAHsummaryALL.pdf.

- Salber EJ. Lay advisers as a community-health resource. Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law. 1979;3:469–478. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3-4-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadler BM, Judge CM, Prout M, Allen JD, Geller AC. Improving breast cancer control via the use of community health workers in South Africa: A critical review. Journal of Oncology, 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/150423. Article ID 150423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KJ, Luque JS, Miladinovic B, Vargas N, Asvat Y, Roetzheim RG, Kumar A. Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20:1580–1598. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M-Y, Song L, Seetoo A, Cai C, Smith G, Oakley D. Culturally competent training program: A key to training lay health advisors for promoting breast cancer screening. Health Education & Behavior. 2007;34:928–941. doi: 10.1177/1090198107304577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]