Abstract

To reduce HIV incidence, prevention programs centered on the use of antiretrovirals require scaling-up HIV testing and counseling (HTC). Home-based HTC services (HBHTC) increase HTC coverage, but HBHTC has only been evaluated during one-off campaigns. Two years after an initial HBHTC campaign (“round 1”), we conducted another HBHTC campaign (“round 2”) in Likoma (Malawi). HBHTC participation increased during round 2 among women (from 74% to 83%, p<0.01). New HBHTC clients were recruited, especially at ages 25 and older. Only 6.9% of women but 15.9% of men remained unreached by HBHTC after round 2. HIV prevalence during round 2 was low among clients who were HIV-negative during round 1 (0.7%), but high among women who first tested during round 2 (42.8%). The costs per newly diagnosed infection increased significantly during round 2. Periodically conducting HBHTC campaigns can further increase HTC, but supplementary interventions to enroll individuals not reached by HBHTC are needed.

Keywords: HIV testing and counseling, Treatment as prevention, Malawi, Home-based services, cost analysis, HIV prevention

Introduction

HIV testing and counseling (HTC) is the gateway to antiretroviral treatment (ART) and it has been associated with the adoption of protective behaviors, particularly among people who are HIV-positive (1, 2). Its centrality in HIV prevention programs has further increased after confirmation that early initiation of ART prevents HIV transmission to uninfected sexual partners (3). Using “treatment as prevention” (TasP) could lead to large reductions in HIV incidence in southern and eastern African countries if HTC becomes “universal”, frequent and is followed by immediate ART initiation regardless of CD4 count (4). Despite recent increases in the number of people tested (5) however, HTC uptake remains low: large proportions of people who are HIV-positive remain unaware of their infection and present for care at highly advanced disease stages (6).

Strategies to increase HTC coverage include routine testing in healthcare settings (7-9), workplace-based services (10), or mobile HTC clinics (11, 12). These approaches however fall short of ensuring universal access to HTC: except pregnant women, only a small proportion of individuals routinely attend health facilities; workplace-based initiatives have limited impact in settings where most of the population is unemployed or works in the informal sector; and mobile clinics still require clients to travel significant distances to the outreach site and/or wait in line for extended periods of time. Mobile clinics are also vulnerable to adverse weather (13) and HIV-related stigma (14). In a recent study, only 37-57% of individuals in communities where mobile HTC clinics were set up were tested over a 3-year period (12).

Home-based HIV testing and counseling (HBHTC) is another approach to increasing access to HTC. During HBHTC, lay counselors offer HTC services directly in the home, to all household members who express interest in undergoing HTC (15). HBHTC is generally conducted during “campaigns”, i.e., short periods of time during which HBHTC providers go “door-to-door” to offer HTC services (16-18). HBHTC completely eliminates transport costs for the client (19) and reduces waiting times (20). It may also reduce the stigma associated with HTC since every household/community member is targeted regardless of risk factors (21). Existing evaluations indicate that HBHTC greatly increases uptake of HTC (15-17, 21-24) and helps identify new HIV cases at earlier stages of the disease (25). The costs of HBHTC also compare favorably to other HTC delivery strategies (11, 16, 22).

The role of HBHTC in scaling-up access to HTC for TasP programs is however unclear. To maximize the impact of TasP on HIV incidence, is it sufficient to conduct one HBHTC campaign, or should HBHTC campaigns be repeated periodically in the same communities? Repeating HBHTC campaigns presents the following advantages: (i) it could provide new HTC opportunities to community members who were not reached during an initial HBHTC campaign or who do not use other HTC services (e.g., facility-based services); (ii) it could foster repeat testing among community members who previously tested HIV-negative and (iii) it may further raise the demand for HTC in target populations. On the other hand, repeating HBHTC campaigns may have limited effects if HBHTC participation declines from one campaign to the next (“campaign fatigue”) or if repeated HBHTC campaigns primarily reach the same individuals who had already participated in an initial campaign, rather than new clients.

Evaluations of HBHTC programs have unfortunately focused on one-off campaigns (17). In this paper, we use data on two HBHTC campaigns conducted between 2006 and 2008 on Likoma Island (Malawi) to document patterns of HBHTC participation, measure HIV prevalence and evaluate costs in repeated HBHTC campaigns.

Methods

a. Study description

The study was conducted on Likoma, a small island of Lake Malawi. The prevalence of HIV on Likoma was 8% among adults aged 18-35 in 2006 (23). For comparison, the national HIV prevalence among 15-49 years old in Malawi were 11.8% and 10.6% in 2004 and 2010, respectively (26, 27). The study was part of the Likoma Network Study (LNS), which investigates sexual networks and HIV transmission(28). The LNS includes a census, an individual survey, and the provision of HBHTC to island residents during “door-to-door” campaigns. HBHTC campaigns were conducted at least one week after all other study components, by a separate team.

The first HBHTC campaign (thereafter, “round 1”) was conducted in February 2006 in 6 villages and has been described elsewhere (23, 28). The second HBHTC campaign (“round 2”) was conducted between August 2007 and April 2008 in all villages of the island. It targeted all adults aged 18-49 years old (N=2,698) who resided on the island at the time of round 2. In this paper, we focus on the cohort of population members who were targeted during both campaigns (N=852).

At the time of the study, client-initiated HTC services were offered at Likoma district hospital. HTC mobile clinics were set up in a few villages of Likoma in 2006 (after round 1) and 2007 (before round 2) as part of Malawi’s national HIV testing week (29, 30). ART became available at the Likoma District Hospital in 2005.

During each campaign, HBHTC was provided by lay counselors certified in HTC by the Malawian Ministry of Health. All counselors were recruited from the mainland to enhance confidentiality (20). HTC was based on two rapid HIV tests used in parallel, Determine (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) and Unigold (Trinity Biotech PLC, Bray, Ireland). Prior to the start of a HBHTC campaign in each village, sensitization meetings were conducted to explain the importance of HTC, demonstrate HTC procedures, provide information about access to ART, and answer questions.

Typical HBHTC sessions lasted 40-60 minutes, with 15-20 minutes for pretest counseling, 15-20 minutes for testing, and the remainder for post-test counseling. Post-test counseling of HIV-positive clients included referral to the Likoma District Hospital for access to treatment and care services. Participants could refuse HIV testing after pretest counseling, and they could also opt not to learn their results after testing. HTC was strictly individual, and we did not provide couples’ counseling. Up to 2 attempts were made to contact clients during round 1, and up to 3 attempts were made during round 2. After completion of HBHTC, participants were provided with a small bar of soap. Population members were offered HBHTC services regardless of their prior use of HIV testing services.

b. Study variables

Main outcomes

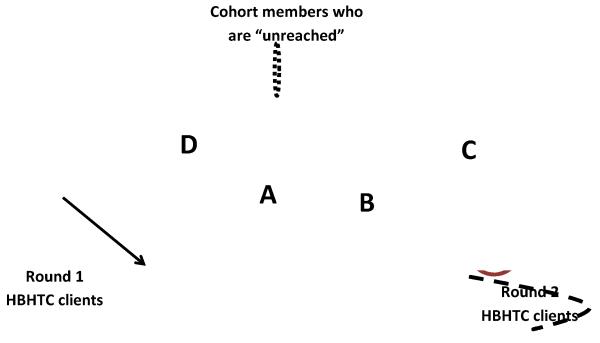

Information on participation in HBHTC campaigns was obtained from campaign records. Cohort members who underwent HBHTC were classified as HBHTC “clients”. If one accepted pre-test counseling but refused testing or refused to learn his/her test results, he/she was not classified as a client. During round 1, all HBHTC clients were “new” HBHTC clients because HBHTC had never been offered on Likoma. During round 2, “new” HBHTC clients were clients who did not participate in HBHTC during round 1, whereas “continuing” HBHTC clients did (figure 1). “Drop-outs” were cohort members who participated in HBHTC during round 1, but not during round 2. Finally, cohort members who did not participate in either round 1 or round 2 were “unreached”.

Figure 1. Classification of cohort members according to their participation in HBHTC campaigns and use of other HIV testing services.

Notes: The dotted black oval represents the entire cohort, whereas the maroon oval repre sents all round 1 HBHTC clients and the light pink oval represents all round 2 HBHTC clients. As a result, the area marked “A” represents “continuing HBHTC clients” (i.e., they participated in both HBHTC rounds). Areas of the pink oval outside of A, i.e., (areas marked “B” or “C”), on the other hand, represent “new HBHTC clients” (i.e., they did not participate in round 1). Areas of the maroon oval outside of “A” repres ent “drop-outs”, i.e., cohort members who participated in round 1 but not in round 2. New HBHTC clients during round 2 are further divided between “repeat testers” (area marked “B”) and “first-time testers” (area marked “C”). Areas outside of A, B, C and D constitute cohort members who were “unreached” through HBHTC.

We used data from the LNS survey to sub-classify new HBHTC clients as either “first-time testers” or “repeat testers”. First-time testers were new HBHTC clients who reported, during the LNS survey, that they had never been tested elsewhere prior to a given HBHTC round. On the other hand, repeat testers reported that they had been tested elsewhere prior to a given HBHTC round. HBHTC clients were considered HIV-positive if they had concordant reactive test results on both rapid HIV tests; they were considered HIV-negative if they had concordant non-reactive test results on both rapid HIV tests or if they had discordant test results (23, 28).

Costs

The costs of HBHTC during each campaign were collected from project accounts and were assessed from a provider’s perspective. Costs analyzed included staff time, transportation, consumables (i.e., HIV test kits, other medical supplies, printing of consent forms), accommodation, training and meetings for community sensitization. The costs of the initial training of HTC counselors were not included in the analysis because the counselors we recruited had already been trained and were either unemployed, working in volunteer jobs or on personal leave from their current job (for a similar approach, see for example 16). Training costs thus only included two days of refresher training provided prior to the start of each campaign. Counselors received a stipend of 10$ a day (25$ for supervisors) during round 1 and $12 a day (30$ for supervisors) during round 2.

For round 2, costs were only available for the total target population of 2,698 island residents; we thus apportioned variable costs to the smaller population targeted by both campaigns. Fixed costs – e.g., transport to Likoma-were not apportioned, and instead were fully allocated to the smaller population subset. All costs were converted to 2007 US dollars. Client time was not assessed. Following other descriptions of the costs of HBHTC (e.g.,16, 22), potential costs incurred by the health system through providing treatment to newly diagnosed individuals, or averted treatment costs through HIV prevention, were not included.

c. Statistical analyses

First, we identified attritors (i.e., individuals who left Likoma or died) after round 1 HBHTC. Subsequent statistical analyses focused on the subset of cohort members who still resided on Likoma at the time of round 2, and were thus offered HBHTC during both rounds. Second, we assessed whether campaign fatigue occurred in Likoma between rounds 1 & 2. To do so, we used χ2 tests to compare HBHTC participation rates during rounds 1 & 2. Third, we estimated what proportions of cohort members a) dropped out of the HBHTC program between rounds 1 & 2, b) became new clients at round 2, and c) remained unreached after round 2. We tested whether such participation patterns were associated with age (<25 years old vs. 25-34 vs. ≥ 35 years old). Fourth, we described the prevalence of HIV among HBHTC clients during rounds 1&2, by prior use of HBHTC and other HTC services. All analyses listed above were conducted separately by gender.

d. Costs analyses

Finally, we calculated the average cost of HBHTC during each round 1) per client tested, 2) per first time tester and 3) per newly diagnosed HIV infection. In the LNS, HBHTC clients were asked whether they had ever been tested prior to a given HBHTC round, but they were not asked about the result of their most recent HIV test. We thus could not determine with precision how many new HIV diagnoses were obtained during each HBHTC campaign. Instead, we estimated a range for the number of newly diagnosed infections during each campaign as follows. For round 2, we first considered that all first-time testers (i.e., area “C” in figure 1) were unaware of their infection, whereas all continuing HBHTC clients who tested HIV-positive during round 1 were aware of their infection. Then we considered two scenarios for new HBHTC clients who were repeat testers and for continuing HBHTC clients who had tested HIV-negative during round 1. In one scenario (“high-awareness”), we assumed that all the members of those two groups who tested HIV-positive during round 2 already knew of their infection; in another scenario (“low-awareness”), we assumed that none of the members of those two groups who tested HIV-positive during round 2 already knew of their infection. We conducted similar calculations for round 1, but during round 1 all HBHTC clients were new HBHTC clients. In the high/low awareness scenario for round 1, all/none of the repeat testers were thus aware of their infection, respectively. We estimated the costs of HBHTC per newly diagnosed infection according to each of these scenarios. Cost analyses included all individuals present on Likoma at the time of a given HBHTC campaign (n = 852 for round 1, n = 764 for round 2).

Results

a. Descriptive statistics

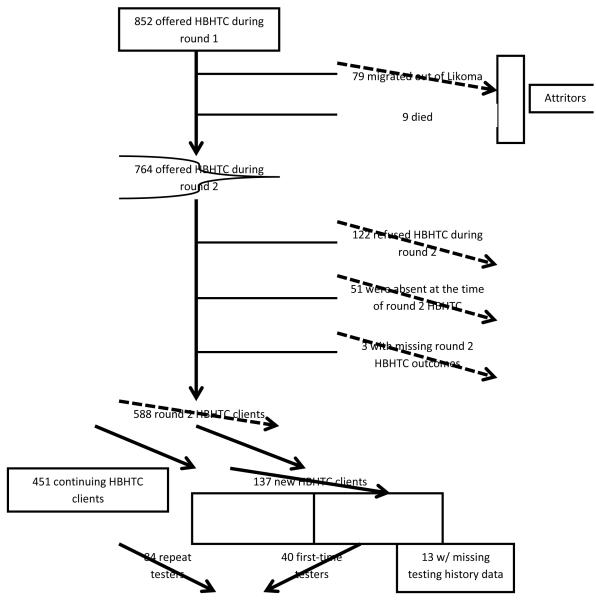

Among the 852 cohort members targeted during round 1, there were 88 attritors: 79 (9.3%) had migrated out of the island and 9(1.1%) had died between the two campaigns (figure 2). Seven hundred and sixty-four cohort members (89.7%) were still residents of Likoma. Attrition from the cohort was associated with HBHTC outcomes during round 1 among men at p<0.1 level, but not among women. Eighty-nine per cent (107/120) of women who did not participate in round 1 were still resident of Likoma during round 2, vs. 91.5% (311/340) of those who participated in round 1 (p=0.45). Among men, 84.4% (114/135) of those who did not participate in round 1 were still resident of Likoma during round 2, vs. 90.3% (232/257) of those who participated in round 1 (p=0.09).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of follow-up and participation in round 2 of the HBHTC campaign on Likoma

b. Was there HBHTC campaign fatigue on Likoma?

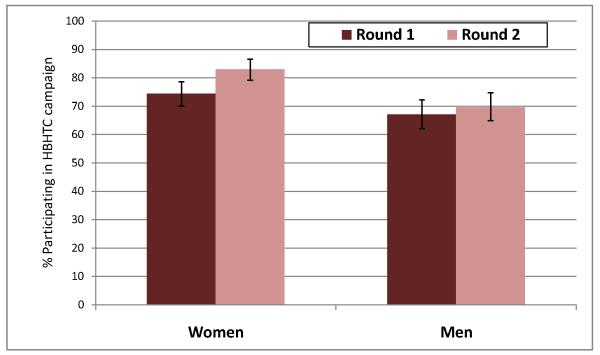

Among the 764 cohort members offered HBHTC during both campaigns, 543 had participated in round 1 (71.1%) and 588 (77.0%) participated in round 2 (p<0.01). Participation increased markedly among women (figure 2), from 74.4% (311/418) during round 1 to 83.0% (347/418) during round 2 (p<0.01). It was stable among men: 67.0% (232/346) during round 1 vs. 69.7% during round 2 (241/346, p=0.51).

c. Were new clients recruited during the second HBHTC campaign?

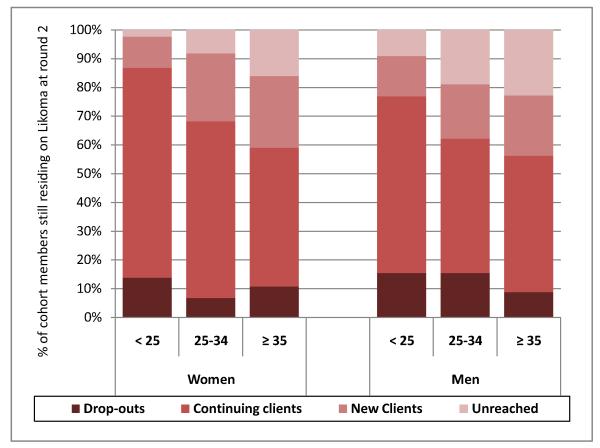

Among round 1 clients, repeat testing was high: 86.8% of women (269/310), and 79.1% (182/230) of men, who participated in round 1 also participated in round 2. Ninety-two participants in round 1 dropped out of the HBHTC program between rounds 1 & 2 (17.0%). As a result, among the 764 members of the cohort offered HBHTC during both rounds 1 and 2, 12.% were drop-outs (92/764), 59.0% were continuing HBHTC clients (451/764) and 17.9% (137/764) became new HBHTC clients during round 2. On the other hand, 11.0% (84/764) remained unreached after two HBHTC campaigns. These patterns differed significantly by gender and age (figure 4). For example, more men dropped out of the HBHTC program, whereas more women remained continuing clients. Similarly, older cohort members were more likely to become new clients during round 2 (e.g., 10.8% of women < 25 years old vs. 25% among women aged ≥ 35 years old). The proportion of unreached cohort members increased sharply with age for both men and women (e.g., from 10% among men < 25 years old to 22% among men aged ≥ 35 years old).

Figure 4. Patterns of repeated uptake of HBHTC after two campaigns on Likoma Island.

Notes: drop-outs are cohort members who participated in round 1, but not in round 2; continuing clients participated in both rounds; new clients participated in round 2 only and unreached cohort members did not participate in any HBHTC round. Proportions depicted in this panel include cohort members residing on Likoma at the time of both campaigns (i.e., non-attritors, n=764). Cohort members who tested positive during HBHTC round 1 are included in the participation rates represented in this panel.

d. HIV prevalence among HBHTC clients

Among round 1 clients, the prevalence of HIV was 10.6% (36/340) among women and 4.7% (12/257) among men (table 1). HIV prevalence did not differ by prior HIV testing history. During round 2, the prevalence of HIV was 10.7% among women (37/346) and 3.3% (8/241) among men. Among continuing HBHTC clients who tested HIV-positive during round 1, all tested HIV-positive again except one female client who had discordant test results (Unigold was reactive, whereas Determine was non-reactive). Among continuing HBHTC clients who tested HIV-negative during round 1, 0.8% of women (2/247) and 0.6% of men (1/177) tested HIV-positive during round 2. Among new HBHTC clients during round 2, the prevalence of HIV varied significantly by prior HIV testing history among women, but not among men: 42.2% (8/19) of female first-time testers were HIV-positive vs. 12.2% (6/49) of female repeat testers (p=0.01).

Table 1.

HIV prevalence among HBHTC campaign participants during rounds 1 & 2.

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % | p-valueg | N | % | p-valueg | |

| Round 1 | ||||||

| All clients a | 36/340 | 10.6% | -- | 12/257 | 4.7% | -- |

| By Prior HIV testing history b | ||||||

| First-time testers | 26/251 | 10.4% | 0.74 | 10/183 | 5.5% | 0.51 |

| Repeat testers | 8/68 | 11.8% | 2/60 | 3.3% | ||

| Round 2 | ||||||

| All clients | 37/346 | 10.7% | -- | 8/240 | 3.3% | -- |

| Among Continuing clients | ||||||

| By HIV results during round 1 c | ||||||

| HIV-positived | 21/22 | 95.5% | <0.001 | 4/4 | 100.0% | <0.001 |

| HIV-negative | 2/247 | 0.8% | 1/177 | 0.6% | ||

| Among new clients | ||||||

| By Prior HIV testing history b | 0.01 | 0.88 | ||||

| First-time testerse | 8/19 | 42.2% | 1/21 | 4.8% | ||

| Repeat testersf | 6/49 | 12.2% | 2/35 | 5.7% | ||

Notes:

All HBHTC clients during round 1 were new HBHTC clients because HBHTC had not been offered in Likoma prior to round 1

because of non-response during the LNS survey, the testing history of 21 women and 14 men who were HBHTC clients during round 1 could not be ascertained. Similarly, some round 2 participants who were new HBHTC clients did not complete the LNS health survey during round 2 (n=12, 9 women and 3 men). As a result, their HIV testing status (repeat tester vs. first-time tester) at the time of round 2 is unknown

HBHTC HIV test results during round 2 were missing for 1 continuing HBHTC client and for 1 new HBHTC client

One HBHTC client who tested HIV-positive during round 1 had discordant HIV test results during round 2

First-time testers are new HBHTC clients who reported never having been tested for HIV prior to round 2

“Repeat testers” are new HBHTC clients who reported having ever been tested for HIV at another location (e.g., district hospital) prior to round 2

The p-value is obtained from a χ2 test of the difference in HIV prevalence between clients by prior HIV testing history.

e. Cost analysis

The overall costs of providing HBHTC increased slightly between rounds 1 & 2, from $7,261.9 to $7,919.2 (table 2). All budget items increased between the two campaigns, except accommodation: during round 2, the HBHTC team rented an unoccupied local house, whereas HBHTC providers stayed at a local guesthouse during round 1. Team productivity in providing HBHTC declined slightly between both rounds: from 4.39 tests per counselor and per day to 4.24. The costs of providing HBHTC per client tested increased from 12.2$ to 13.5$, but the cost per first-time tester increased much more sharply (more than 10-fold), from 16.7$ during round 1 to 198.0$ during round 2. According to the awareness scenarios described above, between 75 and 100% of HIV-infected clients during round 1 were unaware of their infection vs. 20-44% of HIV-infected clients during round 2. The cost per newly diagnosed HIV infection ranged from 151.3$ to 201.7$ during round 1, and from 395.9$ to 879.9$ during round 2 (depending on the awareness scenario).

Table 2.

Estimates of the costs associated with providing HBHTC during each campaign

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Campaign costs | ||

| Training | $210 | $360 |

| Stipends | ||

| Supervisors | $1,012.4 | $1,523.1 |

| HTC counselors | $1,360.0 | $1,665.3 |

| Transport | $650.4 | $846.2 |

| Accommodation | $1,500.0 | $930.8 |

| Community meetings | $200.0 | $300.0 |

| Consumables | $2,125.8 | $2,293.8 |

| Total costs | $7,261.9 | $7,919.2 |

| Team productivity a | 4.39 | 4.24 |

| Campaign Outcomes | ||

| Number of | ||

| Clients tested | 597 | 586 |

| First-time testers | 434 | 40 |

| HIV-positive clients | 48 | 45 |

| Estimated number of HIV-positive clients unaware of their HIV infectionb | ||

| Low awareness | 48 (100%) | 20 (44%) |

| High awareness | 36 (75%) | 9 (20%) |

| Average cost per | ||

| Client tested | $12.2 | $13.5 |

| First-time tester | $16.7 | $198.0 |

| Newly diagnosed HIV infectionc | ||

| Low awareness | $151.3 | $395.9 |

| High awareness | $201.7 | $879.9 |

Source: Likoma Network Study.

Notes: all costs are in 2007 US dollars.

Productivity is measured as the number of clients learning their HIV test results per day and per counselor.

The numbers in parentheses indicated the proportion of HIV-infected clients during each campaign who were unaware of their HIV infection according to a given awareness scenario

All clients HIV-infected considered unaware of their infection are counted as ‘newly diagnosed HIV infections’ in these analyses.

Discussion

In this paper, we investigated participation, HIV case finding and costs during a HBHTC campaign conducted on Likoma Island 2 years after an initial HBHTC campaign achieved > 70% HBHTC participation (23). We found limited evidence of “campaign fatigue” on Likoma: despite high prior uptake of HTC, participation in HBHTC increased between the two HBHTC campaigns. This was particularly the case among women (from 74 to 83%). Repeating HBHTC campaigns also permitted enrolling new clients in HBHTC, particularly among ages 25 and above. A significant proportion of cohort members remained however unreached by HBHTC after two campaigns (6.9% among women and 15.9% among men). During round 2, HIV prevalence was low among continuing HBHTC clients who had tested HIV-negative during round 1 (0.7% HIV-infected) but was high among new HBHTC clients, particularly among those who received their first HIV test results during round 2. Among women, 42.1% of new HBHTC clients who had never been tested elsewhere prior to round 2 were HIV-infected vs. 12.2% among women who had ever been tested elsewhere. During round 1, for comparison, we did not observe an association between HIV prevalence and prior HIV testing history among HBHTC clients (table 1).

The operational costs of providing HBHTC did not vary significantly between the two campaigns. On average, each test cost 12.2-13.5$. This is higher than previous reports (16, 21, 22), with differences largely explained by the HBHTC protocol adopted on Likoma. In our study, household members were revisited 2-3 times if a first contact attempt was unsuccessful vs. only one contact attempt in other studies. The costs of finding an undiagnosed infection likely increased significantly between rounds 1 and 2. This is the case because at the time of round 1, most population members had never been tested whereas this was the case only for a minority prior to round 2.

Our study has important limitations. On the one hand, the HBHTC campaigns were conducted within a research study, i.e., in conditions that may not be possible to recreate in the context of a rapid scale-up of HTC services. Large-scale implementation may require less intensive follow-up of population members (e.g., only one contact attempt) and this may lead to lower HBHTC uptake. It may also require relying on HTC providers recruited among community members, instead of hiring HTC providers outside of the target communities. Scaled-up HBHTC programs may thus not be able to ensure that providers and clients do not know each other, therefore limiting the perceived “confidentiality advantage” of HBHTC over other HTC strategies (20). By its unique geographic location, Likoma also presents advantages in terms of evaluating the implementation of HBHTC campaigns: the target population is well defined and can be conveniently enumerated. This may not be the case in other sub-Saharan settings, particularly in rapidly urbanizing areas and other areas with high migration rates. Second, in addition to the home-based HTC campaigns, Likoma has seen other major HTC scale-up initiatives such as national HIV testing weeks (29, 30). These initiatives may have significantly increased the awareness and acceptability of HTC on the island. The generalizability of our findings may be limited to settings where the supply of other HTC services is similarly strong. Third, we did not offer couples’ HIV testing and counseling (CVCT). Reaching co-residing couples is however an important benefit of offering home-based services (19, 31). It will be critical to determine whether couples (and in particular serodiscordant couples) participate in repeated HBHTC campaigns in future studies. Fourth, we did not investigate the interactions between HBHTC and other testing services. Do repeated HBHTC campaigns negatively affect the demand for, or the supply of, HIV testing at health facilities? If so, the overall benefits of HBHTC for the coverage of HIV testing may be more limited than previously thought. Fifth, our assessment of a respondent’s HIV testing history is based on self-reported data, which are affected by possibly large reporting biases. Nonetheless, our strategy for the measurement of HIV testing histories is widely used to estimate the coverage of HIV testing during surveys (26). Sixth, our measures of the costs of HBHTC did not include the costs of pre-service training of HTC counselors. In doing so, we followed the approach of Negin et al. (16), for example. Such costs need to be included if the implementing agency needs to train new counselors, or if the costs/benefits HBHTC are estimated at the societal level. Seventh, we did not investigate crucial issues of linkage to care services following HBHTC campaigns (25, 32). All campaign participants were provided information about and referred to nearby care services and HAART providers, but the uptake of these services was not ascertained. Eighth, our study does not constitute an assessment of the cost-effectiveness of repeated HBHTC campaigns. This is the case because we did not estimate the number of infections potentially averted by repeated HBHTC, nor did we measure the costs incurred by the health system because of increased demand for treatment and care following HBHTC. Such investigations likely require the use of mathematical models. Finally, we did not investigate whether participation in repeated HBHTC campaigns was associated with risk factors for HIV acquisition/transmission including condom use, sexual behaviors or male circumcision.

Despite these limitations, our results have important implications. They confirm that HBHTC campaigns may be one of the most effective strategies to make progress towards universal access targets in sub-Saharan settings. In particular, HBHTC allows achieving levels of HTC uptake that are considerably higher than those achieved through mobile clinics or facility-based HTC services (12). Our results also suggest that changing patterns of participation and HIV case-finding during repeated HBHTC campaigns should be incorporated in mathematical models used to estimate the potential effects of TasP on HIV incidence (4, 33, 34). Finally, they highlight the need for additional interventions to reach individuals who do not use HBHTC services even after multiple campaigns. If the prevalence of HIV is high among these “unreached” and they do not use other HTC services, they may constitute sustained pockets of high HIV viral load that may limit (or negate) the impact of TasP. It is not clear whether additional repetitions of HBHTC campaigns will constitute the most cost-effective approach to reaching such populations. Other strategies such as provider-initiated partner notification (35, 36) or self-testing (37) should be investigated.

Figure 3. Participation in two consecutive HBHTC campaigns on Likoma Island.

Notes: proportions depicted in this panel include only cohort members residing on Likoma at the time of both campaigns (i.e., excluding attritors, n=764). Cohort members who tested positive during HBHTC round 1 are included in the participation rates represented in this panel. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Acknowledgements

This research received support through the National Institute of Child Health and Development (grant nos. RO1 HD044228 and RO1 HD/MH41713), National Institute on Aging (grant no. P30 AG12836), the Boettner Center for Pensions and Retirement Security at the University of Pennsylvania, and the National Institute of Child Health and Development Population Research Infrastructure Program (grant no. R24 HD-044964), all at the University of Pennsylvania, as well as through grant no. R03 HD071122 to Columbia University. The authors thank the inhabitants of Likoma for their collaboration.

References

- 1.Roth DL, Stewart KE, Clay OJ, van Der Straten A, Karita E, Allen S. Sexual practices of HIV discordant and concordant couples in Rwanda: effects of a testing and counselling programme for men. Int J STD AIDS. 2001 Mar;12(3):181–8. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, Zulu I, Trask S, Fideli U, et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 2003 Mar 28;17(5):733–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jul 18; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009 Jan 3;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . Towards universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nash D, Wu Y, Elul B, Hoos D, El Sadr W. Program-level and contextual-level determinants of low-median CD4+ cell count in cohorts of persons initiating ART in eight sub-Saharan African countries. AIDS. 2011 Jul 31;25(12):1523–33. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834811b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pope DS, Deluca AN, Kali P, Hausler H, Sheard C, Hoosain E, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of provider-initiated (opt-out) HIV counseling and testing of tuberculosis patients in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 Jun 1;48(2):190–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181775926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassett IV, Giddy J, Nkera J, Wang B, Losina E, Lu Z, et al. Routine voluntary HIV testing in Durban, South Africa: the experience from an outpatient department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Oct 1;46(2):181–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31814277c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macpherson P, Lalloo DG, Choko AT, Mann GH, Squire SB, Mwale D, et al. Suboptimal patterns of provider initiated HIV testing and counselling, antiretroviral therapy eligibility assessment and referral in primary health clinic attendees in Blantyre, Malawi*. Trop Med Int Health. 2012 Feb 1;17(4):507–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbett EL, Dauya E, Matambo R, Cheung YB, Makamure B, Bassett MT, et al. Uptake of workplace HIV counselling and testing: a cluster-randomised trial in Zimbabwe. PLoS Med. 2006 Jul;3(7):e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grabbe KL, Menzies N, Taegtmeyer M, Emukule G, Angala P, Mwega I, et al. Increasing access to HIV counseling and testing through mobile services in Kenya: strategies, utilization, and cost-effectiveness. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Jul 1;54(3):317–23. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ced126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sweat M, Morin S, Celentano D, Mulawa M, Singh B, Mbwambo J, et al. Community-based intervention to increase HIV testing and case detection in people aged 16-32 years in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Thailand (NIMH Project Accept, HPTN 043): a randomised study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 May 3; doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maheswaran H, Thulare H, Stanistreet D, Tanser F, Newell ML. Starting a Home and Mobile HIV Testing Service in a Rural Area of South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Mar 1;59(3):e43–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182414ed7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buscher AL. Challenges to community-based voluntary HIV testing and counselling. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Jan;12(1):10–1. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70343-7. Comment Letter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Were W, Mermin J, Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Kaharuza F. Home-based model for HIV voluntary counselling and testing. Lancet. 2003 May 3;361(9368):1569. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Negin J, Wariero J, Mutuo P, Jan S, Pronyk P. Feasibility, acceptability and cost of home-based HIV testing in rural Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2009 Aug 14;8:849–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bateganya M, Abdulwadud OA, Kiene SM. Home-based HIV voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) for improving uptake of HIV testing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD006493. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006493.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tumwesigye E, Wana G, Kasasa S, Muganzi E. Nuwaha F. High uptake of home-based, district-wide, HIV counseling and testing in Uganda. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011 Nov;24(11):735–41. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matovu JK, Makumbi FE. Expanding access to voluntary HIV counselling and testing in sub-Saharan Africa: alternative approaches for improving uptake, 2001-2007. Trop Med Int Health. 2007 Nov;12(11):1315–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angotti N, Bula A, Gaydosh L, Kimchi EZ, Thornton RL, Yeatman SE. Increasing the acceptability of HIV counseling and testing with three C’s: Convenience, confidentiality and credibility. Social Science & Medicine. 2009 Jun;68(12):2263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tumwesigye E, Wana G, Kasasa S, Muganzi E, Nuwaha F. High uptake of home-based, district-wide, HIV counseling and testing in Uganda. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010 Nov;24(11):735–41. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menzies N, Abang B, Wanyenze R, Nuwaha F, Mugisha B, Coutinho A, et al. The costs and effectiveness of four HIV counseling and testing strategies in Uganda. AIDS. 2009 Jan 28;23(3):395–401. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321e40b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helleringer S, Kohler HP, Frimpong JA, Mkandawire J. Increasing uptake of HIV testing and counseling among the poorest in sub-Saharan countries through home-based service provision. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Jun 1;51(2):185–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819c1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bateganya MH, Abdulwadud OA, Kiene SM. Home-based HIV voluntary counseling and testing in developing countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006493. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006493.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wachira J, Kimaiyo S, Ndege S, Mamlin J, Braitstein P. What is the impact of home-based HIV counseling and testing on the clinical status of newly enrolled adults in a large HIV care program in Western Kenya? Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Jan 15;54(2):275–81. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malawi Demographic and Health Survey . National Statistical Office & ORC Macro2005; Calverton, Maryland: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malawi Demographi and Health Survey . Calverton. National Statistical Office and ORC Macro2011; Marylan: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helleringer S, Kohler HP, Chimbiri A, Chatonda P, Mkandawire J. The Likoma Network Study: Context, data collection, and initial results. Demogr Res. 2009;21:427–68. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.21.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National HIV testing and counseling week, 16th-21st July 2007. Malawi Ministry of Health and National AIDS Commission2007; Lilongwe: [Google Scholar]

- 30.National HIV testing and counseling week, 17th-22nd July 2006. Malawi Ministry of Health and National AIDS Commission2006; Lilongwe, Malawi: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matovu JK. Preventing HIV transmission in married and cohabiting HIV-discordant couples in sub-Saharan Africa through combination prevention. Curr HIV Res. 2010 Sep 1;8(6):430–40. doi: 10.2174/157016210793499303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Losina E, Bassett IV, Giddy J, Chetty S, Regan S, Walensky RP, et al. The “ART” of linkage: pre-treatment loss to care after HIV diagnosis at two PEPFAR sites in Durban, South Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodd PJ, Garnett GP, Hallett TB. Examining the promise of HIV elimination by ’test and treat’ in hyperendemic settings. AIDS. 2010 Mar 13;24(5):729–35. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833433fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hallett TB, Gregson S, Dube S, Mapfeka ES, Mugurungi O, Garnett GP. Estimating the resources required in the roll-out of universal access to antiretroviral treatment in Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Infect. 2011 Jun 2; doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown L, Miller W, Kamanga G, Nyirenda N, Mmodzi P, Pettifor A, et al. HIV partner notification is effective and feasible in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for HIV treatment and prevention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;56(5):437–42. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318202bf7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armbruster B, Helleringer S, Kohler HP, Mkandawire J, Kalilani-Phiri L. Exploring the relative costs of contact tracing in increasing HIV case-finding in sub-Saharan countries: the case of Likoma Island (Malawi) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Jun 30; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822a9fa8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choko AT, Desmond N, Webb EL, Chavula K, Napierala-Mavedzenge S, Gaydos CA, et al. The uptake and accuracy of oral kits for HIV self-testing in high HIV prevalence setting: a cross-sectional feasibility study in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS Med. 2011 Oct;8(10):e1001102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]