Abstract

Aim: To determine if the NADPH oxidase isoform Nox4 contributes to increased H2O2 generation in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) pulmonary arteries (PA), and to identify downstream signaling targets of Nox4 that contribute to vascular remodeling and vasoconstriction. Results: PPHN was induced in lambs by antenatal ligation of the ductus arteriosus at 128 days gestation. After 9 days, lungs, PA, and PA smooth muscle cells (PASMC) were isolated from control and PPHN lambs. Increased expression of p22phox and Nox4 in PPHN lungs, PA, and PASMC was associated with increased reactive oxygen species in PPHN PA, increased protein thiol oxidation in PPHN PASMC, and a decreased activity of extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD) in the lungs and PASMC. Nox4 small interfering RNA (siRNA) decreased Nox4 expression and thiol oxidation and increased the ecSOD activity in PPHN PASMC. An increased activity of nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) and expression of its target gene cyclin D1 were detected in PPHN lungs, PA, and PASMC. Nox4 siRNA and catalase attenuated these increases in PASMC, and catalase decreased cyclin D1 expression in PPHN lungs. Innovation: This study demonstrates for the first time that Nox4 expression is elevated in a lamb model of neonatal pulmonary hypertension. It identifies increased NFκB and cyclin D1 expression and a decreased ecSOD activity as targets of increased Nox4 signaling. Conclusion: PPHN increases p22phox and Nox4 expression and activity resulting in elevated H2O2 levels in PPHN PA. Increased H2O2 induces vasoconstriction via mechanisms involving ecSOD inactivation, and stimulates vascular remodeling via NFκB activation and increased cyclin D1 expression. Approaches that inhibit the pulmonary arterial Nox4 activity may attenuate vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling in PPHN. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 1765–1776.

Introduction

At birth, the pulmonary vascular resistance decreases, allowing the pulmonary blood flow to increase 10-fold. This fetal-to-newborn transition is regulated by complex physiological and biochemical processes, which are necessary to promote pulmonary artery (PA) vasodilation. Abnormalities in the transition at birth produce persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), a life-threatening clinical disorder of newborn infants (39). PPHN is characterized by an elevated pulmonary vascular resistance, right-to-left extrapulmonary shunting of deoxygenated blood, and severe hypoxemia. Pathological findings include pulmonary vascular remodeling and smooth muscle hyperplasia (17), such that successful prevention and treatment of PPHN must address defects in the vascular structure and function.

Innovation.

H2O2 has been implicated in the pathophysiology of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), but the sources of increased pulmonary artery H2O2 and its effects on downstream signaling remain poorly understood. This study is the first to identify increased Nox4 expression in a model of neonatal pulmonary hypertension. This study also is the first to show that Nox4-derived H2O2 depresses the extracellular superoxide dismutase activity and increases the nuclear factor-kappa B activity, both of which contribute to a positive feedback loop that amplifies H2O2 production and enhances vascular dysfunction and cell cycle progression. Nox4 may represent a diagnostic marker and a potential therapeutic target for the detection and treatment of PPHN.

A lamb model involving antenatal ligation of the ductus arteriosus followed by delivery at near-term gestation has been used to simulate PPHN. These newborn lambs display increased PA pressure, pulmonary vascular remodeling, and other physiological changes consistent with clinical PPHN (31, 49). Recent evidence suggests that PPHN lambs also exhibit elevated pulmonary vascular oxidant stress and a diminished antioxidant activity relative to control lambs (7, 47), which may promote vasoconstriction directly and by impairing the activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and downstream cyclic guanozine monophosphate (cGMP) signaling (5, 14, 37).

Additional studies indicate that elevated H2O2 levels contribute to the vascular dysfunction of PPHN. In pulmonary vascular cells isolated from normal fetal lambs, exogenous H2O2 decreased the extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD) activity (47), impaired cGMP production (13), decreased eNOS expression (44), and stimulated cell proliferation (45). In PPHN lambs, in vitro administration of catalase to PA smooth muscle cells (PASMC) restored the normal ecSOD activity, decreased cytosolic reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, and restored normal cGMP signaling (12, 47). Similarly, in vivo administration of intratracheal catalase to ventilated PPHN lambs improved oxygenation, increased the ecSOD activity, and increased lung cGMP levels (12, 47). Together, these data suggest that H2O2 contributes to pulmonary hypertension via dysregulation of NO-mediated vasodilation, and that catalase treatment improves oxygenation by restoring normal signaling pathways. However, the mechanisms that give rise to increased H2O2 levels in PPHN PA are currently unknown.

We have shown previously that endogenous catalase and glutathione peroxidase activities were unchanged in PPHN PA (48), suggesting that increased H2O2 generation rather than decreased removal is predominant. There is evidence that the NADPH oxidase (Nox) isoform Nox4 generates H2O2 in the rat aortic SMC (10), and Nox4 has been shown to mediate proliferation and migration in PASMC (24). While other Nox isoforms require an assembly of multiple cytosolic subunits for activation, the Nox4 activity is regulated primarily at the level of its expression (36) and via its interaction with the membrane-spanning p22phox subunit (2). We hypothesized that the increased Nox4/p22phox activity contributes to increased H2O2 levels, vascular dysfunction, and vascular remodeling that leads to PPHN. Thus, the purpose of this study was to quantify Nox4 and p22phox expression in the lungs and PASMC from PPHN lambs, and to determine the effects of Nox4 knockdown on ROS generation and signaling in PPHN PASMC.

Results

We previously observed an increase in H2O2 in PA isolated from fetal PPHN lambs relative to fetal controls, as determined by catalase-sensitive dichlorodihydrofluoresceindiacetate (DCF-DA) fluorescence (48). Accordingly, PA DCF-DA fluorescence was also increased in lung sections from PPHN lambs and was decreased in sections coincubated with polyethylene glycol (PEG)–catalase (Fig. 1A). In agreement with our previous study (48), DCF-DA fluorescence was over fourfold higher in fetal PPHN PA relative to controls (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Dichlorodihydrofluoresceindiacetate (DCF-DA) fluorescence is increased in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) pulmonary artery (PA). (A) Lung tissue sections were incubated with 5 μM DCF-DA for 30 min and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Sequential sections were coincubated with 100 U/ml polyethylene glycol (PEG)–catalase. (B) Fluorescence intensities within PA were quantified by MetaMorph software and normalized to the pixel number. Values are expressed relative to fetal controls. n≥5 animals. *p<0.05 versus control vehicle. †p<0.05 versus PPHN vehicle.

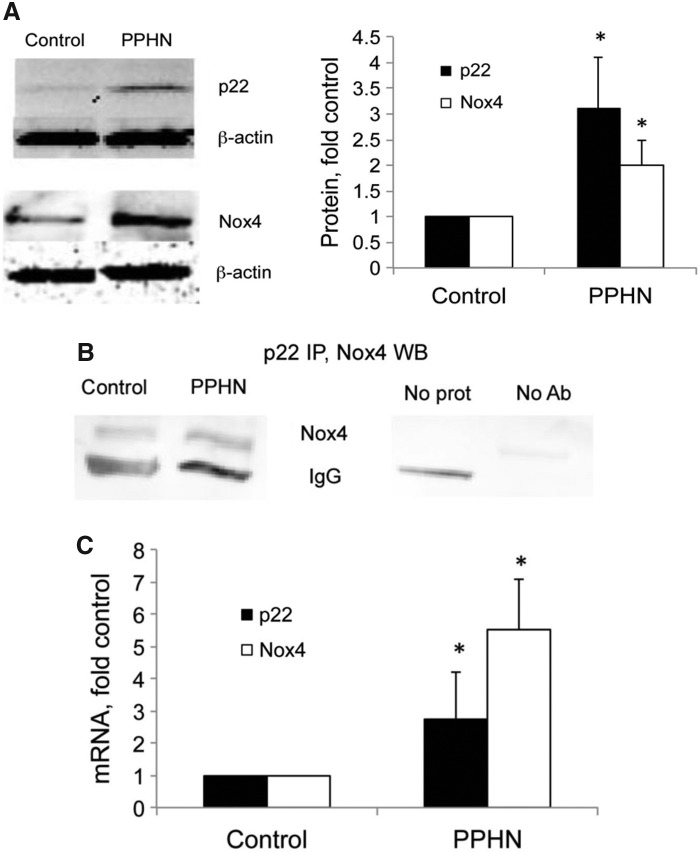

To identify the source of increased H2O2 in PA, we determined expression of the H2O2-generating p22phox/Nox4 isoform of Nox. The p22phox/Nox4 activity is regulated primarily by subunit expression (2), and we found significant increases in Nox4 and p22phox protein levels from fetal PPHN lambs relative to fetal controls (Fig. 2A). We also detected a significant increase in the Nox2 protein in agreement with our previous reports (7); however, the Nox2 isoform differs from Nox4 in that it predominantly generates superoxide and its activity requires the assembly of additional subunits. Immunoprecipitation studies indicated an increased association between Nox4 and p22phox in the lung protein from fetal PPHN lambs relative to fetal controls (Fig. 2B). We used lung extracts to generate sufficient amounts of protein for immunoprecipitation. However, p22phox and Nox4 (and Nox2) mRNA levels were also significantly increased in extracts from PPHN PA (Fig. 2C). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated localization of the p22phox and Nox4 protein in the PA (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

FIG. 2.

p22phox and Nox4 expression is increased in PPHN lungs and PA. (A) Representative blots for p22phox and Nox4, and Nox1 and Nox2, from control and PPHN lungs. Lysates from two different animals in each group are depicted. Lysates not loaded adjacently on the gel are separated by a black bar. Images depicted are from the same Western blot and from the same exposure, and images for each antibody were processed identically. Band intensities were normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to controls. Supplementary Figure S2 depicts full Western blots for Nox isoforms in lung protein lysates. (B) Protein lysates from two different control (C) and two different PPHN (P) lungs were immunoprecipitated using a Nox4 antibody and the Western blot probed using a p22phox antibody. The left lane shows the flow-through (non-immunoprecipitated) protein from a PPHN lysate (PPHN-FT). The right lanes show the immunoprecipitation controls omitting the precipitating antibody (NoAb) or omitting the input protein (NoProt). The precipitating IgG antibody is also presented in the representative image. (C) Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers to Nox1, Nox2, Nox4 and p22phox and RNA from control and PPHN PA. Expression levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA levels and expressed relative to controls. *p<0.05. n≥5 animals.

Nox4 and p22phox gene expression is regulated by the transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) (26, 28). We quantified levels of the inhibitory protein IκB as an indicator of the NFκB activity in PPHN lungs, and found that IκB protein levels were 52% lower in lung extracts from PPHN lambs relative to control lambs (Fig. 3A). A decreased IκB protein was also evident in PPHN PA as detected by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3B). We also detected increased colocalization of the DNA binding NFκB subunit p65 with nuclei in PPHN PA relative to controls (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Protein levels of the nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) inhibitory protein IκB are decreased in PPHN lungs and PA. (A) Representative blots for IκB from control and PPHN lungs. Lysates from two different animals in each group are depicted. Band intensities were normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to control lungs. *p<0.05. n≥4 animals. (B) Immunohistochemistry for IκB in lung sections from control and PPHN lambs. PA and airways (AW) are indicated. Corresponding light fields are depicted below the fluorescent photomicrographs. (C) Immunohistochemistry for p65 (red) in lung sections from control and PPHN lambs at 10×and 40×objective lens magnification. Sections were incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) to identify nuclei and to indicate nuclear localized p65 (purple).

PPHN is associated with pulmonary vascular remodeling, which may be due, in part, to increased proliferation of PASMC. Cyclin D1, an activator of cell cycle progression, is also induced by NFκB (15). Cyclin D1 protein levels were 1.4-fold higher in lung homogenates from PPHN lambs relative to control lambs (Fig. 4A), while cyclin D1 mRNA levels were over twofold higher in PPHN PA (Fig. 4B). The increased cyclin D1 protein in PPHN PA was also evident from immunohistochemical studies (Supplementary Fig. S1).Cyclin D1 stimulates an increase in proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), which promotes cell cycle progression. The PCNA protein levels were 2.1-fold higher in PPHN lungs relative to controls (Fig. 4A). Conversely, protein levels of the cell cycle inhibitor p21 were decreased in PPHN lungs, while cyclin A and cyclin B1 protein levels were not significantly different (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Cyclin D1 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression is increased in PPHN lungs and PA. (A) Representative blots for cyclinA, cyclin B1, p21, cyclin D1, and PCNA from control and PPHN lungs. Lysates not loaded adjacently on the gel are separated by a black bar. Images depicted are from the same Western blot and from the same exposure, and images for each antibody were processed identically. Band intensities were normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to control lungs. (B) Real-time PCR using primers to cyclin D1 and RNA from control and PPHN PA. Expression levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA levels and expressed relative to controls. *p<0.05. n≥5 animals.

We then used PASMC isolated from fetal control and fetal PPHN lambs to identify mechanisms that regulate Nox4 expression and to identify targets of Nox4 signaling. We have shown previously that PPHN PASMC maintain a PPHN phenotype up to passage 5 (47). When normalized to β-actin, p22phox expression was threefold higher and Nox4 expression twofold higher in PPHN PASMC relative to controls (Fig. 5A). Accordingly, the p22phox/Nox4 association was increased in PPHN PASMC relative to controls as detected by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5B). The p22phox and Nox4 mRNA levels were increased by 2.8-fold and 5.5-fold, respectively, in PPHN PASMC relative to controls (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Increased p22phox and Nox4 expression in PPHN PASMC. (A) Representative blots for p22phox and Nox4 from control and PPHN PASMC lysates. Band intensities were normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to control PASMC. (B) Protein lysates from (A) were immunoprecipitated using a p22phox antibody and the Western blot probed using a Nox4 antibody. The right lanes show the immunoprecipitation controls omitting the precipitating antibody (No Ab) or omitting the input protein (No Prot). The precipitating IgG antibody is also presented in the representative image. (C) Real-time PCR using primers to p22phox and Nox4. Expression levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA levels and expressed relative to controls. *p<0.05. n≥4.

Using an ovine Nox4-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotide, we were able to suppress the Nox4 protein by 54% in PPHN PASMC relative to cells treated with a scrambled siRNA oligonucleotide (Supplementary Fig. S3A). There was a corresponding 80% decrease in Nox4 mRNA in PPHN PASMC transfected with the Nox4-specific siRNA relative to cells transfected with the scrambled siRNA (Supplementary Fig. S3B).We also determined that Nox4 siRNA transfection did not alter Nox2 mRNA levels (1.15±0.28-fold relative to cells transfected with scrambled siRNA).

We recently demonstrated that PASMC from PPHN lambs displayed increased cytosolic protein thiol oxidation relative to controls, as determined by the redox-sensitive probe reduction-oxidation-sensitive green fluorescent protein (RoGFP) (47). In agreement, RoGFP oxidation was over fourfold higher in PPHN PASMC transfected with a scrambled siRNA relative to control cells (Fig. 6A). Nox4 knockdown decreased RoGFP oxidation by 76% relative to PPHN PASMC transfected with the scrambled siRNA, but had no effect on basal RoGFP oxidation in control PASMC (Fig. 6A). PPHN PASMC infected with an adenovirus expressing catalase also displayed decreased basal RoGFP oxidation relative to cells infected with an empty viral vector (Fig. 6A) indicating that H2O2 oxidizes the probe, in agreement with a previous study (42). RoGFP oxidation in scrambled siRNA-transfected control and PPHN cells was similar to our previous results using untreated cells (47). However, the higher basal RoGFP oxidation in PPHN PASMC infected with the additional empty vector or catalase viruses may be a result of virus-induced ROS in these cells. Supplementary Figure 4 shows representative flow cytometry data for RoGFP. We previously reported that the ecSOD activity was reduced to 38%±18% of control values in PPHN PASMC, and that treatment with PEG-catalase restored the ecSOD activity (47). In the present study, we found that Nox4 siRNA increased the ecSOD-specific activity by 62%±12% in PPHN PASMC relative to cells transfected with the scrambled siRNA (Fig. 6B), but had no effect on the MnSOD or CuZnSOD activity. Nox4 siRNA decreased ecSOD expression, a pattern similar to what was reported with catalase (47).

FIG. 6.

Nox4 small interfering RNA (siRNA) attenuates protein thiol oxidation and increases the extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD) activity in PPHN PASMC. (A) Control and PPHN PASMC were transfected with a scrambled siRNA or a siRNA specific to ovine Nox4, and then infected with an adenovirus expressing reduction-oxidation-sensitive green fluorescent protein (RoGFP) in the cytosol. RoGFP oxidation in lysates was determined by flow cytometry and the % oxidation determined by fully oxidizing and fully reducing the probe. Control and PPHN PASMC were infected with an adenovirus expressing catalase or with an empty viral vector and % RoGFP oxidation determined. Between 5000 and 20000 RoGFP-positive cells were quantified for each sample. (B) SOD isoform activity and expression in PASMC lysates was determined from cells transfected with a scrambled or a Nox4-specific siRNA. Expression levels were normalized to β-actin, and activities were normalized to the protein content and expressed relative to scrambled siRNA controls. *p<0.05. †p<0.05 vs PPHN vector. n≥4.

Using a consensus NFκB DNA-binding sequence fused to a luciferase reporter, we found that the basal NFκB promoter activity was 4.1-fold higher in PPHN PASMC transfected with the scrambled siRNA relative to control cells (Fig. 7A). Transfection with the Nox4-specific siRNA decreased the NFκB promoter activity to 69% and 50% of scrambled siRNA levels in control and PPHN PASMC, respectively (Fig. 7A). Treatment with the NFκB inhibitor helenalin decreased the Nox4 and p22phox protein levels by 60% and 51%, respectively, in PPHN PASMC (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 7.

NFκB activity is increased in PPHN PASMC and is attenuated by Nox4 siRNA. (A) Control and PPHN PASMC were transfected with a scrambled siRNA or a siRNA specific to ovine Nox4, and then transfected with a plasmid containing five consensus κB sites in tandem upstream of a luciferase reporter. Relative light units were determined in a luminometer, normalized to an internal renilla luciferase control plasmid, and expressed relative to control cell lysates. *p<0.05 versus control PASMC transfected with scrambled siRNA. †p<0.05 versus PPHN PASMC transfected with scrambled siRNA. n≥3. (B) PPHN PASMC were treated with Helenalin (Hel) for 24 h and p22phox and Nox4 levels determined by Western blotting. Expression levels were normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to untreated (UTD) samples. *p<0.05 versus untreated PPHN PASMC. n≥4.

Cyclin D1 protein levels (Fig. 8A) and the cyclin D1 promoter–luciferase activity (Fig. 8B) were twofold and sevenfold higher, respectively, in PPHN PASMC relative to control cells. The PCNA protein was 1.7-fold higher, while the p21 protein was 0.69-fold, in PPHN PASMC relative to controls (Fig. 8A). The cyclin D1 promoter includes a previously characterized NFκB binding site (15, 20), and incubation with the NFκB inhibitor helenalin decreased the cyclin D1 promoter–luciferase activity to 0.36-fold and 0.23-fold in control and PPHN PASMC, respectively, relative to untreated cells (Fig. 8B). Transfection with the Nox4-specific siRNA decreased the cyclin D1 promoter–luciferase activity to 0.4-fold relative to the scrambled siRNA in PPHN PASMC, but had no effect in control cells (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

Cyclin D1 and PCNA expression is increased in PPHN PASMC. (A) Representative blot for cyclin D1, PCNA, and p21 from control and PPHN PASMC lysates. Lysates not loaded adjacently on the gel are separated by a black bar. Images depicted are from the same Western blot and from the same exposure, and images for each antibody were processed identically. Band intensities were normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to control PASMC. (B) Control and PPHN PASMC were transfected with a plasmid containing the human cyclin D1 promoter region, including a previously characterized NFκB-binding site. Some cells were then treated with the NFκB inhibitor Helenalin. Relative light units were determined in a luminometer, normalized to an internal renilla luciferase control plasmid, and expressed relative to control cell lysates. (C) Control and PPHN PASMC were transfected with a scrambled or Nox4-specific siRNA and 24 h later transfected with the cyclin D1 promoter–luciferase construct. Relative light units were determined in a luminometer, normalized to an internal renilla luciferase control plasmid, and expressed relative to scrambled siRNA lysates from control PASMC. *p<0.05 versus control cells untreated or transfected with scrambled siRNA. †p<0.05 versus PPHN cells untreated or transfected with scrambled siRNA. n≥3.

The siRNA data presented in Figures 7 and 8 suggest that Nox4-derived H2O2 may stimulate the NFκB activity and cyclin D1 expression in PPHN. Infection with an adenovirus overexpressing cytosolic catalase decreased the NFκB promoter activity by 52% (Fig. 9A) and cyclin D1 mRNA by 42% (Fig. 9B) in PPHN PASMC relative to cells transfected with an empty adenoviral vector. PPHN lambs that were ventilated with oxygen at birth for 24 h and administered a single dose of intratracheal catalase showed reduced lung protein levels of cyclin D1 and PCNA relative to PPHN lambs ventilated with oxygen alone (Fig. 9C, D).

FIG. 9.

Catalase decreases cyclin D1 expression in PPHN. PPHN PASMC were infected with an adenovirus expressing catalase in the cytosol (A), and then transfected with the NFκB reporter plasmid. Relative light units were determined in a luminometer, normalized to an internal renilla luciferase control plasmid, and expressed relative to lysates treated with an empty adenoviral vector. (B) PPHN PASMC were infected with an adenovirus expressing catalase in the cytosol or with an empty adenoviral vector, and cyclin D1 mRNA levels were quantified 3 days later by real-time PCR. *p<0.05 versus cells infected with the empty viral vector. n≥5. (C) Representative Western blots for cyclin D1 and PCNA from lungs of PPHN lambs ventilated with oxygen for 24 h with or without intratracheal PEG-catalase. (D) Band intensities were normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to PPHN lambs ventilated with oxygen alone. *p<0.05. n≥5 animals.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify potential sources of increased H2O2 generation in PASMC of fetal lambs with PPHN, which could lead to better detection and treatment strategies for neonates with PPHN, a disease associated with high morbidity and mortality. Increased H2O2generation and signaling in PPHN PA may negatively impact expression or activity of multiple enzymes important for the normal fetal to newborn transition, including eNOS, ecSOD, soluble guanylatecyclase, and phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) (13, 48). Scavenging H2O2 with intratracheal catalase improved oxygenation and vasorelaxation in ventilated PPHN lambs and enhanced the lung activity of ecSOD (47), which is localized primarily within the pulmonary vasculature (29, 33, 34). ecSOD augments NO signaling by attenuating the rapid interaction between superoxide and NO (21). Accordingly, intratracheal catalase increased cGMP levels and decreased the PDE5 activity in PA isolated from ventilated PPHN lambs (12).

In the current study, we demonstrate increased expression of the Nox subunits Nox4 and p22phox in the lungs and PA of PPHN lambs. Increased Nox4/p22phox expression was previously reported in the lungs of adult mice with chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (32), but this is the first report in a fetal or neonatal model of pulmonary hypertension. The Nox4/p22phox activity is regulated primarily at the level of expression of its subunits (2, 36), and has been shown to increase H2O2 levels in vascular SMC (10). Our data lead us to conclude that the increased Nox4/p22phox expression and activity are important sources of abnormal H2O2-mediated signaling in the PA of fetal PPHN lambs. We also demonstrate an increased Nox4/p22phox expression and association in PASMC isolated from fetal PPHN lambs. These cells maintain a PPHN phenotype in culture, including the increased cytosolic ROS levels, decreased ecSOD activity, and increased PDE5 activity, and are thus, a useful tool to investigate the mechanisms of dysregulated signaling pathways in PPHN (12, 47).

The specific mechanisms that induce Nox4 and p22phox expression in PPHN are currently unknown. Our findings of increased mRNA levels in PPHN PA and PASMC suggest that increased transcription and/or increased mRNA stability is involved. Other studies using systemic vascular SMC have shown that p22phox transcription is activated by several ROS-sensitive factors, including NF-κB (28) and AP-1 (27), while Nox4 transcription is upregulated by NFκB (28) and HIF-1α (9). Nox-derived H2O2 is known to amplify its own production via a feed-forward mechanism in vascular disease (8), and exposure to exogenous H2O2 increases superoxide generation via Nox in vascular SMC (25). These data suggest that H2O2 generated by Nox4/p22phox may also upregulate ROS production by other Nox isoforms. In the current study, we found an increase in expression of the superoxide generating isoform Nox2, but not Nox1, in PPHN PA and PASMC. We previously reported increased expression of the Nox2 activating protein p67phox in fetal PPHN lambs relative to fetal controls (7), and we recently demonstrated that apocynin, an inhibitor of leukocyte Nox2 and a scavenger of H2O2 in vitro (18), decreased p22phoxand p47phoxexpression in ventilated PPHN lambs (46). While superoxide generated by Nox2 can contribute to elevated H2O2 in PPHN, our siRNA data suggest that Nox4 is the major source of increased ROS in PPHN PASMC. However, we speculate that increased H2O2 in PPHN PA may stimulate a positive feedback mechanism involving upregulation of Nox subunit expression via ROS-sensitive transcription factors, such as NFκB. Additional studies are required to identify the initial sources of ROS that lead to increased Nox expression, thereby sustaining ROS generation in PPHN. Further, identification of the inhibitory pathways that prevent the amplification of ROS in control lambs may reveal new therapeutic targets for PPHN.

We investigated a role for Nox4/p22phox in the elevated cytosolic protein thiol oxidation in PPHN PASMC that we have demonstrated previously (47). We chose a siRNA approach to knock down expression of Nox4, since the p22phox subunit also associates with other Nox isoforms. We demonstrated increased oxidation of the redox-sensitive ratiometric probe RoGFP in PPHN cells relative to control cells transfected with a scrambled siRNA, in close agreement with our previous studies using nontransfected cells (47). In contrast, knock down of Nox4 reduced oxidation of the RoGFP probe by 76%, leading us to conclude that the increased basal Nox4/p22phox expression and activity is a major contributor to increased protein thiol oxidation in PPHN PASMC. Our previous studies demonstrated that increased cytosolic ROS levels depress the ecSOD activity in PPHN PASMC relative to control cells (47), and that the ecSOD activity is restored by catalase. H2O2 has been shown to inactivate purified ecSOD (19, 30), and our current studies suggest that Nox4-derived H2O2 suppresses the ecSOD activity in PPHN PASMC. By scavenging extracellular superoxide, ecSOD plays an important role in augmenting NO signaling in the pulmonary vasculature. When the ecSOD activity is diminished, NO reacts rapidly with elevated superoxide to form peroxynitrite, thus attenuating NO-mediated vasodilation. Our findings suggest that inhibition of Nox4 restores the endogenous ecSOD activity, which could improve the efficacy of treatment for PPHN.

Nox4-derived H2O2 has the potential to stimulate vascular dysfunction by activating downstream signaling pathways via ROS-sensitive transcription factors. NFκB is a heterodimeric protein that is sequestered in the cytoplasm of unstimulated cells through an interaction with the regulatory protein IκB (41). Activation of NFκB by stimuli, including ROS, involves the phosphorylation of IκB by I kappa B kinase. This targets IκB for protein degradation (41), allowing NFκB to translocate into the nucleus where it operates as a transcription factor. The current study is the first to show that the basal NFκB activity is elevated in PPHN PASMC, and that Nox4 knockdown and catalase attenuate this increase in an activity. We also detected decreased levels of the inhibitory protein IκB in the lungs and PA of PPHN lambs, suggesting that the NFκB activity is increased in vivo. Recent studies demonstrated the increased NFκB activity in small pulmonary arterial lesions and in macrophages from explanted lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (22), and that inhibition of NFκB via pharmacological inhibition or delivery of a nanoparticle-mediated NFκB decoy attenuated monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in rats (22, 35). We previously reported increased expression of other NFκB target genes in PPHN, including inducible nitric oxide synthase (14), which may contribute to elevated levels of peroxynitrite in PPHN (46) and increase vasoconstriction of the neonatal pulmonary circulation (4, 23). We suggest that the Nox4-induced NFκB activity may be involved in several dysregulated pathways in PPHN, and could be an important potential therapeutic target in PPHN.

NFκB also induces cyclin D1 (15), which regulates the transition from G0/G1 to S phase in the cell cycle by activating cdk4/cdk6-mediated phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb) (38). Once phosphorylated, Rb releases sequestered transcription factors, including members of the E2F family, which are free to activate the expression of target genes and allow cell cycle progression. Genes activated by E2F transcription factors include PCNA, an important regulator of DNA replication, chromosome segregation, and cell cycle progression (6, 40). Antenatal ductal ligation induces rapid pulmonary arterial remodeling over a period of 8–10 days as evidenced in the light field panels in Figure 3. In the current study, we demonstrate elevated expression of cyclin D1 and PCNA in PPHN PA and PASMC. Increased PA muscularization can contribute to hypertension by increasing the contractile potential of the smooth muscle layer and by decreasing the efficacy of endogenous and exogenous vasodilators. We have shown previously that exogenous H2O2 stimulated PASMC growth, while antioxidants and Nox inhibitors attenuated serum-induced cell proliferation (43, 45). The current study indicates that Nox4 and NFκB mediate the increased cyclin D1 expression in PPHN PASMC, while our in vivo data demonstrate that catalase reduces cyclin D1 and PCNA expression in the lungs of ventilated PPHN lambs. These data suggest that H2O2 scavenging or inhibition of Nox4, NFκB, and cyclin D1 in utero may attenuate the development of PA muscularization in PPHN.

In summary, we demonstrate that increased expression of the p22phox and Nox4 subunits of Nox increases ROS levels in PA and PASMC isolated from neonatal lambs with PPHN. Downstream targets of ROS produced by Nox4 include NFκB, which increases expression of the cell cycle regulatory protein cyclin D1. We also speculate that NFκB stimulates a positive feedback mechanism that sustains p22phox/Nox4 expression and ROS generation. Nox4-derived ROS may also impair NO signaling by inhibiting the ecSOD activity. Figure 10 depicts our proposed signaling pathway. Early detection of PPHN may improve the efficacy of treatment and outcome for patients by providing the option of in utero intervention. Our data suggest that increased Nox4 expression and elevated H2O2 levels may represent clinical biomarkers of PPHN, while the continued development of pharmacologic inhibitors of Nox, such as GKT137831 (3) and VAS2870 (1) may yield additional therapeutic agents. Interventions to block Nox4 signaling may be beneficial in the treatment of PPHN by restoring the normal pulmonary vascular tone and by attenuating pulmonary vascular remodeling.

FIG. 10.

Proposed pathway showing increased Nox4 expression and H2O2 levels in PPHN PA, leading to a decreased ecSOD activity and vasoconstriction, and increased NFκB and cyclin D1 leading to pulmonary vascular remodeling. Nox4 inhibition and catalase treatment block the pathway.

Materials and Methods

Animals

This protocol was approved by the Laboratory Animal Care committee at the University at Buffalo. Time-dated pregnant ewes were obtained from the Swartz family farm in Attica, New York. Fetal lambs underwent antenatal ligation of the ductus arteriosus at 128 days gestation (term 143–145 days) to induce pulmonary hypertension as previously described (31, 50). Lambs were delivered 9 days later and sacrificed with an overdose of thiopental sodium and exsanguination before their first breath. Some PPHN lambs were delivered and mechanically ventilated with 100% O2 for 24 h with or without 20,000 U/kg intratracheal PEG-catalase (Sigma) at birth (47). Fifth generation PA and lung tissue were collected for further analysis.

In situ analysis of hydrogen peroxide generation

Frozen lung sections were exposed to 5 μM H2DCF-DA (Molecular Probes) for 30 min as previously described (48) and coincubated with 100 U/ml PEG-catalase (Sigma) where appropriate. Images from sequential lung sections were captured as described in the Supplementary Data, and the average fluorescent intensities (to correct for differences in pixel number) of PA quantified using Metamorph imaging software (Fryer). Muscularized arteries ∼50–100 μm in diameter were selected for the analysis, and 5–10 arteries were quantified for each animal.

Cell culture

Primary cultures of PASMC from control and PPHN fetal lambs were isolated by the explant technique as described previously (45) and maintained in culture as described in the Supplementary Data.

Western blot analysis

Isolated frozen lung and PA tissue were homogenized and the total protein collected using the PARIS kit (Ambion). Lysates were prepared from PASMC using the lysis buffer (Millipore, and proteins analyzed by Western blotting as previously described (13, 14). Expression within each Western blot was normalized to β-actin. Data are shown as fold relative to control lambs.

Immunoprecipitation

The lung and PASMC protein were prepared as described above and 500 μg incubated with a 4 μg anti-Nox4 or anti-p22phoxantibody (Santa Cruz), respectively, at 4°C overnight with gentle rocking using the Catch and Release Immunoprecipitation System according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore). The eluted protein was analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-p22phox or anti-Nox4 antibody (Santa Cruz) as above.

Quantitative reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA from PA and PASMC was prepared and analyzed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described in the Supplementary Data.

siRNA transfection

An ovine Nox4-specific Silencer Select siRNA (Invitrogen), 5′-GUA CUA UUC UUG AUG AUU ATT-3′ (sense), 5′-UAA UCA UCA AGA AUA GUA CCA-3′ (antisense), was used to knock down Nox4, and a scrambled siRNA was used as a control (Silencer Negative Control No.1 siRNA, Invitrogen). After optimization studies, cells were transfected with 12.5 nM siRNA using LipofectamineRNAiMAX and Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A complete medium was added after 4 h, and after 24 h, the medium was aspirated and changed to the complete medium. Analyses were performed 72 h after transfection.

Detection of ROS

PASMC in the serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium without phenol red and with antibiotics and antimycotics were infected in 60-mm culture dishes with 100 PFU/cell of a RoGFP adenoviral construct. RoGFP is a previously characterized ratiometric fluorescent probe sensitive to cellular oxidative stress (11, 16). The percentage oxidation of RoGFP in each sample was determined by flow cytometry as described in the Supplementary Data.

SOD purification and activity assays

The activity of each SOD isoform was determined from PASMC protein lysates as described in the Supplementary Data.

Plasmid DNA transfection and luciferase assays

NFκB and cyclin D1 promoter activities were determined by transfecting cells with plasmids carrying promoter–luciferase constructs as described in the Supplementary Data. Where appropriate, cells were transfected with siRNA as above or treated with 10 μM Helenalin (Calbiochem) before luciferase assays.

Adenoviral infection

Cells were infected with an adenoviral construct expressing cytosolic catalase or an empty adenoviral vector, Y5 (100–750 PFU/cell; University of Iowa) 48–72 h before an analysis.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean±SEM with each N representing a different lamb for in vivo studies. Results were analyzed by a two-sided unpaired t-test using Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- cGMP

cyclic guanozine monophosphate

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DCF-DA

dichlorodihydrofluoresceindiacetate

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- ecSOD

extracellular superoxide dismutase

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- IKK

I kappa B kinase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- NFκB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- Nox

NADPH oxidase

- PA

pulmonary arteries

- PASMC

pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PDE5

phosphodiesterase type 5

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PPHN

persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn

- Rb

retinoblastoma protein

- RoGFP

reduction-oxidation-sensitive green fluorescent protein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT

reverse transcription

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- WST

water soluble tetrazolium salts

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Altenhofer S. Kleikers PW. Radermacher KA. Scheurer P. Rob Hermans JJ. Schiffers P. Ho H. Wingler K. Schmidt HH. The NOX toolbox: validating the role of NADPH oxidases in physiology and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2327–2343. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambasta R. Kumar P. Griendling K. Schmidt H. Busse R. Brandes R. Direct interaction of the novel Nox proteins with p22phox is required for the formation of a functionally active NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45935–45941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoyama T. Paik YH. Watanabe S. Laleu B. Gaggini F. Fioraso-Cartier L. Molango S. Heitz F. Merlot C. Szyndralewiez C. Page P. Brenner DA. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (nox) in experimental liver fibrosis: GKT137831 as a novel potential therapeutic agent. Hepatology. 56:2316–2327. doi: 10.1002/hep.25938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belik J. Pan J. Jankov R. Tanswell A. Peroxynitrite inhibits relaxation and induces pulmonary artery muscle contraction in the newborn rat. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1384–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black SM. Johengen MJ. Soifer SJ. Coordinated regulation of genes of the nitric oxide and endothelin pathways during the development of pulmonary hypertension in fetal lambs. Pediatr Res. 1998;44:821–830. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bravo R. Macdonald-Bravo H. Existence of two populations of cyclin/proliferating cell nuclear antigen during the cell cycle: association with DNA replication sites. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:1549–1554. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan LA. Steinhorn RH. Wedgwood S. Mata-Greenwood E. Roark EA. Russell JA. Black SM. Increased superoxide generation is associated with pulmonary hypertension in fetal lambs: a role for NADPH oxidase. Circ Res. 2003;92:683–691. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000063424.28903.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai H. NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent self-propagation of hydrogen peroxide and vascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;96:818–822. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163631.07205.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diebold I. Petry A. Hess J. Görlach A. The NADPH oxidase subunit NOX4 is a new target gene of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2087–2096. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-12-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dikalov S. Dikalova A. Bikineyeva A. Schmidt H. Harrison D. Griendling K. Distinct roles of Nox1 and Nox4 in basal and angiotensin II-stimulated superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1340–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dooley C. Dore T. Hanson G. Jackson W. Remington S. Tsien R. Imaging dynamic redox changes in mammalian cells with green fluorescent protein indicators. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22284–22293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrow K. Wedgwood S. Lee K. Czech L. Gugino S. Lakshminrusimha S. Schumacker P. Steinhorn R. Mitochondrial oxidant stress increases PDE5 activity in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrow KN. Groh BS. Schumacker PT. Lakshminrusimha S. Czech L. Gugino SF. Russell JA. Steinhorn RH. Hyperoxia increases phosphodiesterase 5 expression and activity in ovine fetal pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:226–233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrow KN. Lakshminrusimha S. Reda WJ. Wedgwood S. Czech L. Gugino SF. Davis JM. Russell JA. Steinhorn RH. Superoxide dismutase restores eNOS expression and function in resistance pulmonary arteries from neonatal lambs with persistent pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L979–L987. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90238.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guttridge D. Albanese C. Reuther J. Pestell R. Baldwin AJ. NF-kappaB controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5785–5799. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson G. Aggeler R. Oglesbee D. Cannon M. Capaldi R. Tsien R. Remington S. Investigating mitochondrial redox potential with redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein indicators. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13044–13053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haworth S. Pulmonary vascular remodeling in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 1988;93:133S–138S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heumüller S. Wind S. Barbosa-Sicard E. Schmidt H. Busse R. Schröder K. Brandes R. Apocynin is not an inhibitor of vascular NADPH oxidases but an antioxidant. Hypertension. 2008;51:211–217. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hink HU. Santanam N. Dikalov S. McCann L. Nguyen AD. Parthasarathy S. Harrison DG. Fukai T. Peroxidase properties of extracellular superoxide dismutase: role of uric acid in modulating in vivo activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1402–1408. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000027524.86752.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joyce D. Bouzahzah B. Fu M. Albanese C. D'Amico M. Steer J. Klein JU. Lee RJ. Segall JE. Westwick JK. Der CJ. Pestell RG. Integration of Rac-dependent regulation of cyclin D1 transcription through a nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25245–25249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung O. Marklund S. Geiger H. Pedrazzini T. Busse R. Brandes R. Extracellular superoxide dismutase is a major determinant of nitric oxide bioavailability: in vivo and ex vivo evidence from ecSOD-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2003;93:622–629. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000092140.81594.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura S. Egashira K. Chen L. Nakano K. Iwata E. Miyagawa M. Tsujimoto H. Hara K. Morishita R. Sueishi K. Tominaga R. Sunagawa K. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of nuclear factor kappaB decoy into lungs ameliorates monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;53:877–883. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.121418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakshminrusimha S. Russell JA. Wedgwood S. Gugino SF. Kazzaz JA. Davis JM. Steinhorn RH. Superoxide dismutase improves oxygenation and reduces oxidation in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1370–1377. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-676OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lassegue B. Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases: functions and pathologies in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;30:653–661. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W. Miller FJ. Zhang H. Spitz D. Oberley L. Weintraub N. H(2)O(2)-induced O(2) production by a non-phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase causes oxidant injury. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29251–29256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102124200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manea A. Manea S. Gafencu A. Raicu M. Regulation of NADPH oxidase subunit p22(phox) by NF-kB in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2007;113:163–172. doi: 10.1080/13813450701531235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manea A. Manea S. Gafencu A. Raicu M. Simionescu M. AP-1-dependent transcriptional regulation of NADPH oxidase in human aortic smooth muscle cells: role of p22phox subunit. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:878–885. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.163592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manea A. Tanase L. Raicu M. Simionescu M. Transcriptional regulation of NADPH oxidase isoforms, Nox1 and Nox4, by nuclear factor-kappaB in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 2010;396:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marklund SL. Extracellular superoxide dismutase and other superoxide dismutase isoenzymes in tissues from nine mammalian species. Biochem J. 1984;222:649–655. doi: 10.1042/bj2220649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marklund SL. Properties of extracellular superoxide dismutase from human lung. Biochem J. 1984;220:269–272. doi: 10.1042/bj2200269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morin FC., 3rd. Ligating the ductus arteriosus before birth causes persistent pulmonary hypertension in the newborn lamb. Pediatr Res. 1989;25:245–250. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nisbet R. Graves A. Kleinhenz D. Rupnow H. Reed A. Fan T. Mitchell P. Sutliff R. Hart C. The role of NADPH oxidase in chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:601–609. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0145OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nozik-Grayck E. Suliman HB. Piantadosi CA. Extracellular superoxide dismutase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:2466–2471. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oury TD. Day BJ. Crapo JD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase in vessels and airways of humans and baboons. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:957–965. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sawada H. Mitani Y. Maruyama J. Jiang B. Ikeyama Y. Dida F. Yamamoto H. Imanka-Yoshida K. Shimpo H. Mizoguchi A. Maruyama K. Komada Y. A nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitor pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate ameliorates pulmonary hypertension in rats. Chest. 2007;132:1265–1274. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serrander L. Cartier L. Bedard K. Banfi B. Lardy B. Plastre O. Sienkiewicz A. Forro L. Schlegel W. Krause K. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J. 2007;406:105–114. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaul PW. Yuhanna IS. German Z. Chen Z. Steinhorn RH. Morin III FC. Pulmonary endothelial NO synthase gene expression is decreased in fetal lambs with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L1005–L1012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherr CJ. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell Metab. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinhorn RH. Neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:S79–S84. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c76cdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoimenov I. Helleday T. PCNA on the crossroad of cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:605–613. doi: 10.1042/BST0370605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Traenckner E. Wilk S. Baeuerle P. A proteasome inhibitor prevents activation of NF-{kappa}B and stabilizes a newly phosphorylated form of I{kappa}B-{alpha} that is still bound to NF-{kappa}B. EMBO J. 1994;15:5433–5441. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waypa G. Marks J. Guzy R. Mungai P. Schriewer J. Dokic D. Schumacker P. Hypoxia triggers subcellular compartmental redox signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2010;106:526–535. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wedgwood S. Black SM. Induction of apoptosis in fetal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells by a combined superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L305–L312. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00382.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wedgwood S. Black SM. Endothelin-1 decreases endothelial NOS expression and activity through ETA receptor-mediated generation of hydrogen peroxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L480–L487. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00283.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wedgwood S. Dettman RW. Black SM. ET-1 stimulates pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation via induction of reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1058–L1067. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.5.L1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wedgwood S. Lakshminrusimha S. Farrow KN. Czech L. Gugino SF. Soares F. Russell JA. Steinhorn RH. Apocynin improves oxygenation and increases eNOS in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L616–L626. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00064.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wedgwood S. Lakshminrusimha S. Fukai T. Russell JA. Schumacker PT. Steinhorn RH. Hydrogen peroxide regulates extracellular superoxide dismutase activity and expression in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1497–1506. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wedgwood S. Steinhorn RH. Bunderson M. Wilham J. Lakshminrusimha S. Brennan LA. Black SM. Increased hydrogen peroxide downregulates soluble guanylate cyclase in the lungs of lambs with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L660–L666. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00369.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wild LM. Nickerson PA. Morin FC., 3rd. Ligating the ductus arteriosus before birth remodels the pulmonary vasculature of the lamb. Pediatr Res. 1989;25:251–257. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zayek M. Cleveland D. Morin FC., 3rd. Treatment of persistent pulmonary hypertension in the newborn lamb by inhaled nitric oxide. J Pediatr. 1993;122:743–750. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.