Abstract

Sulfatase 2 (Sulf-2) has been previously shown to be upregulated in breast cancer. Sulf-2 removes sulfate moieties on heparan sulfate proteoglycans which in turn modulate heparin binding growth factor signaling. Here we report that matrix detachment resulted in decreased Sulf-2 expression in breast cancer cells and increased cleavage of poly ADP-ribose polymerase. Silencing of Sulf-2 promotes matrix detachment induced cell death in MCF10DCIS cells. In an attempt to identify Sulf-2 specific inhibitor, we found that proteasomal inhibitors such as MG132, Lactacystin and Bortezomib treatment abolished Sulf-2 expression in multiple breast cancer cell lines. Additionally, we show that Bortezomib treatment of MCF10DCIS cell xenografts in mouse mammary fat pads significantly reduced tumor size, caused massive apoptosis and more importantly reduced Sulf-2 levels in vivo. Finally, our immunohistochemistry analysis of Sulf-2 expression in cohort of patient derived breast tumors indicates that Sulf-2 is significantly upregulated in autologous metastatic lesions compared to primary tumors (p < 0.037, Pearson correlation, Chi-Square analysis). In all, our data suggest that Sulf-2 might play an important role in breast cancer progression from ductal carcinoma in situ into an invasive ductal carcinoma potentially by resisting cell death.

Keywords: Sulfatase 2, Growth factor, Breast cancer

Introduction

Heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPGs) are highly sulfated molecules that serve as co-receptors for many heparin binding growth factors (HBGF) [1, 2]. The 6-O sulfate moiety on HSPGs to which several of the HBGFs bind to are desulfated by two HS editing enzymes known as heparan sulfatases -1 and -2 resulting in altered signaling [3]. Sulfatases -1 and -2 remove sulfate moities from HSPGs and this action affects ternary complex formation between heparin binding ligands such as bFGF2, and its cognate receptor, FGFR2 and co-receptor HSPGs [2]. Previous reports indicate both tumor suppressor and tumor promoter roles for Sulf-2 [4, 5]. Sulf-2 was found to be overexpressed in breast cancers [4] whereas Sulf-1 was largely downregulated [6]. However, the role of Sulf-2 in promoting breast tumorigenesis is not completely understood.

Matrix detachment leads to cell death in several cancer cells including premalignant breast cancer cells [7]. Resistance to this form of cell death provides survival advantage to the breast cancer cells to migrate to distant organs [7]. In the present study, we have evaluated the role of Sulf-2 using a cell line which forms ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) comedo structures when injected into mammary fat pad [8]. Increased proliferation of epithelial cells, loss of acinar organization and filling of the luminal space has been shown in MCF10DCIS model, a well characterized xenograft progression model of DCIS to invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) [9].

Matrix Metallopreotease (MMP) activation is often associated with progression to IDC. These enzymes are involved in the degradation of extracellular matrix, growth factors, and cytokines and cell associated adhesion and signaling receptors [10, 11]. MMPs have been associated with highly invasive cancers and contribute to tumor progression, invasion and metastasis.

In this study, we show that Sulf-2 plays an important role in matrix detachment induced cell death in breast cancer cells. Furthermore, treatment of breast cancer cells with proteasome inhibitor such as bortezomib attenuated Sulf-2 expression. Significant association of Sulf-2 with highly metastatic tumors confirmed our in vitro findings and supports the notion that Sulf-2 is upregulated in breast cancer and can be targeted by proteasomal inhibitors.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

Breast cancer cell lines MCF-7, MCF10AT1 and MCF10DCIS were grown as described previously [8, 12, 13]. Primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-Sulf-2 (1:500 dilution), a gift from Dr Lewis Roberts (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Antibodies used in theses studies are anti-β-actin (1:10,000 dilution, Sigma), anti-MMP9 (1:1,000 dilution, Abcam), anti-cleaved caspase 3 (1:1,000) and anti-cleaved PARP (1:1,000) from cell signaling Tech Inc. MCF10DCIS cells were obtained from Dr Fred Miller (Wayne State University, Detroit, MI) and were tested and authenticated recently by Taconic Inc. Bortezomib was obtained from Mayo Pharmacy and Selleck Chemicals. QVD-OPH was obtained from MP Biomedicals LLC. MG132 and lactacystin were obtained from Sigma.

Western immunoblotting

Cell lysates were prepared as previously described and equal amounts of protein were used in immunoblots [14]. Samples were boiled in Lammeli buffer and were resolved on SDS-PAGE followed by transfer to PVDF membrane and immunoprobed with indicated antibodies.

Mouse mammary fat pad injections

MCF10DCIS xenografts were generated by injecting MCF10DCIS cells into mouse mammary fat pads. 1.0 × 106 cells in 0.1 ml of matrigel were subcutaneously injected at each nipple of gland #5 of female nude mice. Excised xenografts were either fixed in formalin buffer or frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen or stored at −80 °C. For bortezomib treatment, mice received bortezomib (0.150 and 0.300 mg/kg) twice weekly up to 5th week. Each group in bortezomib experiments contained 18 mice (six mice were harvested at each interval). All animal work was conducted under protocols approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and housed in institutional animal facilities. Primary tumor volumes was calculated with the formula V = 1/2 a × b2, where “a” is the longest tumor axis, and “b” is the shortest tumor axis. Each specimen of xenografts obtained from control and bortezomib treated group were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) for morphological analysis.

Gelatin zymography

MMP-2 and MMP-9 enzymatic activity in mouse derived xenografts was performed by SDS-PAGE gelatin zymography. Gelatinases present in the tissue lysates degrade gelatin in the SDS-PAGE leaving a clear white band after coomassie staining of the gel. Tissue samples were homogenized in the lysis buffer [350 mM NaCl, 0.25 % Nonidet P-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM glycerol phosphate, 1 mM sodium ortho-vanadate, and 30 % glycerol with protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma)]. Equal amounts of protein were denatured in the absence of reducing agent and electrophoresed in 7.5 % SDS-PAGE containing 0.1 % (w/v) gelatin. The gel was incubated in the presence of 2.5 % Triton X-100 at room temperature for 2 h and subsequently at 37 °C over might in 10 mM CaCl2, 0.15 M NaCl, and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5). The gel was stained with 0.25 % Coomassie Blue.

Small interfering RNA transductions and shRNAs

Lenitviral supernatants of Short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) vectors obtained from Sigma against Sulf-2 were generated as described previously [15]. Target sequence used for Sulf-2 shRNAs (HW13): CCACAACACCTACACCAACAA. Target sequence for Sulf-2 shRNAs (HW11): CAAGGGT TACAAGCAGTGTAA. Lentivirus particles were produced by transient transfection of two different plasmids targeting Sulf-2 (pLKO.1-Sulf-2) and pLKO.1 non-target control (NTC) along with packaging vectors (pVSV-G and pGag/pol) in 293T cells as previously described [16].

Real time PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared using TRIZOL reagent, reverse-transcribed with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified using SYBR-Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) by using specific primers for human Sulf-2 and ribosomal 18S subunit (Applied Biosystems) in a Light Cycler (BioRad Chromo 4, Hercules, CA). All experiments were conducted at least three times.

Immunohistochemistry

Representative sections of each specimen were stained with H&E. For immuno-histochemistry, breast tumor specimens on a tissue microarray embedded in paraffin were cut at 5–7 μm, mounted on glass and dried overnight at 37 °C. All sections, then, were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a graded alcohol series and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). PBS was used for all subsequent washes and for antiserum dilution. Tissue sections were quenched sequentially in 3 % hydrogen peroxide in aqueous solution and blocked with PBS-6 % non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Slides then were incubated at 4 °C overnight with a rabbit polyclonal antiserum specific for Sulf-2 [17] at final 1:500 dilution in PBS-3 % non-fat dry milk. After three washes in PBS to remove the excess of antiserum, the slides were incubated with diluted goat anti-rabbit biotinylated antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) at 1:200 dilution in PBS-3 % non-fat dry milk for 1 h. All the slides then were processed by the ABC method (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. Diamonobenzidine (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was used as the final chromogen and hematoxylin was used as the nuclear counterstain. Negative controls for each tissue section were prepared by leaving out the primary antiserum. All samples were processed under the same conditions. The expression levels of Sulf-2 stained cells per field (250×) at light microscopy was calculated and compared in different specimens by two separate observers (A.B. and L.L.) in a double blinded fashion and described as: score 0 (absent); 1 (very low); 2 (moderate); and 3 (high). For statistical analysis we combined scores 0 and 1 as (1) and scores 2 and 3 as (2). An average of 22 fields was observed for each breast specimens. Clinical information was extracted for each specimen, and statistical analyses were performed by L.L and M.V.

Statistical analyses

Pearson’s correlation test was used to assess relationship between clinical parameters and immunohistochemical data. p values <0.05 were regarded as statistical significant in Chi-square tests at α = 0.05. JMP software (Version 6.0, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) were used for statistical analyses. Sulf-2 expression was dichotomized as low (staining score 1) and high (staining score 2) to determine the clinical significance of Sulf-2 expression in Chi-Square analysis.

Results

Matrix detachment or anoikis downregulates Sulf-2 expression in breast cancer cell lines

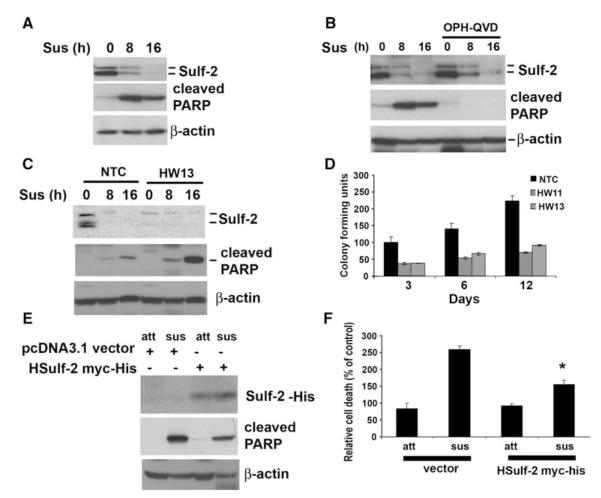

To determine the effect of matrix detachment on Sulf-2, MCF10AT1 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells were plated in poly-HEMA coated low attachment plates for the indicated time intervals. Western blot analysis with anti-Sulf-2 antibody in MCF10DCIS and in MCF-7 cells indicates that Sulf-2 was downregulated as early as 8 h with complete downregulation at 16 h (Fig. 1a; Fig. S1a, b). Two bands of Sulf-2 were detected which have previously shown to be glycosylated form of Sulf-2 [15]. Anoikis induction resulted in apoptosis of these cells as detected by cleaved PARP on immunoblots (Fig. 1a). To determine whether Sulf-2 downregulation was the cause or consequence of apoptosis, we subjected MCF10DCIS cells to anoikis and co-treated the cells with pan caspase inhibitor QVD-OPH as indicated. Western blot with anti-PARP antibody revealed that cleaved PARP was detected in cells undergoing anoikis but not in cells treated with QVD-OPH (Fig. 1b). However, Sulf-2 downregulation due to matrix detachment was not reversible even in presence of pan caspase inhibitor QVD-OPH. Treatment of QVD-OPH during matrix detachment significantly rescued cell death as revealed by trypan blue staining (data not shown). These data indicate that Sulf-2 downregulation upon matrix detachment is independent of apoptosis. We further asked whether depletion of Sulf-2 sensitized cells to apoptosis due to matrix detachment. To address this question, we stably downregulated Sulf-2 in MCF10DCIS cells using lentiviral shRNA targeting Sulf-2 as previously described [15, 16]. NTC cells and Sulf-2 depleted clones (HW13 and HW11) were subjected to matrix detachment for 16 h. Western blot analysis indicates that Sulf-2 depleted cells showed enhanced expression of cleaved PARP compared to NTC clones (Fig. 1c). To further evaluate the role of Sulf-2 on survival upon matrix detachment, we subjected NTC and Sulf-2 knockdown clones to matrix detachment for 24 h followed by their transfer to adhesive polystyrene plates. Colony forming units were counted for indicated time intervals. Sulf-2 depletion clearly showed decreased survival compared to NTC (Fig. 1d). In order validate data obtained from silencing of Sulf-2, we tested the effect of Sulf-2 overexpression on anoikis mediated cell death. MCF10DCIS cells were transfected with vector or Sulf-2-myc/his plasmid and subjected to matrix detachment for 16 h. Western blot analysis indicated that over-expression of Sulf-2 leads to reduced PARP cleavage. Similarly, trypan blue analysis also suggests that Sulf-2 over-expression resulted in decreased cell death (Fig. 1f). Collectively, these data indicate that Sulf-2 downregulation might promote cell death during matrix detachment.

Fig. 1.

Matrix detachment attenuates Sulf-2 expression in MCFDCIS cells. a MCF10DCIS cells were suspended for indicated time intervals on poly-HEMA coated plates and cells were collected and cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis using anti-Sulf-2 antibody, anti-cleaved PARP and anti-beta actin antibodies. Doublet bands of Sulf-2 are indicative of glycosylated forms of protein. b MCF10DCIS cells were suspended for indicated time intervals on poly-HEMA coated plates in absence of presence of QVD-OPH (10 μM) and cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis using anti-Sulf-2, anti-cleaved PARP and anti-β-actin antibodies. Doublet bands of Sulf-2 are indicative of glycosylated forms of protein. c NTC clones and Sulf-2 depleted MCF10DCIS clone was suspended in poly-HEMA coated plates for indicated intervals and cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis using anti-Sulf-2, anti-cleaved PARP and anti-β-actin antibodies. d NTC clones and Sulf-2 depleted MCF10DCIS clone was suspended in poly-HEMA coated plates for 16 h and followed by plating on regular culture dishes for indicated days and colony forming units were counted. e MCF10DCIS cells were transfected with vector (pcDNA 3.1 myc/his) or Sulf-2-myc/his plasmid and subjected to matrix detachment for 16 h followed by Western blot analysis with anti-His, anti-cleaved PARP and anti-β-actin antibodies. Western blot analysis indicated that over-expression of Sulf-2 leads to reduced PARP cleavage. f Trypan blue analysis of samples described in (e) was performed to detect the extent of cell death. Data suggests that Sulf-2 over-expression resulted in decreased cell death. Sus Suspended cells, Att Attached cells, h hour, HW11 and HW13 (clones with stable depletion of Sulf-2)

Proteasome inhibitors downregulate Sulf-2 expression in breast cancer cell lines

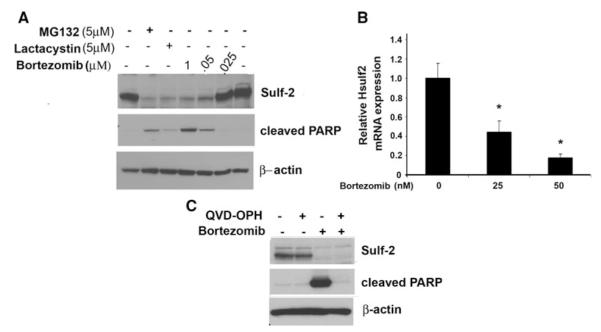

We next postulated that by inhibiting Sulf-2 (by chemical inhibitor), it might prevent tumor growth. At present, specific Sulf-2 inhibitors have not been identified. Therefore, in an attempt to identify inhibitors of Sulf-2, by serendipity we found that proteasomal inhibitors might attenuate Sulf-2 expression. To test this, MCF10DCIS and MCF10AT1 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of proteasomal inhibitors, MG132, Lactacystin and Bortezomib at indicated concentrations. Immunoblot analysis revealed that proteasomal inhibitors treatment results in downregulation of Sulf-2 expression (Fig. 2a). Bortezomib treatment also diminished Sulf-2 expression in MCF10AT1 and MCF-7 cells (Fig. S1b, c). Of note, bortezomib and MG132 treatment in MCF10DCIS cells exhibited upregulation of apoptotic marker protein such as cleaved PARP (Fig. 2a, middle panel). We next tested whether bortezomib treatment altered mRNA levels of Sulf-2. Real time analysis showed that bortezomib treatment effectively downregulated Sulf-2 mRNA expression in MCF10DCIS cells (Fig. 2b). To rule out the possibility that bortezomib treatment might result in apoptosis and hence Sulf-2 is downregulated as a consequence of apoptosis, MCF10DCIS cells were treated with bortezomib and pan caspase inhibitor QVD-OPH. Despite treatment with QVD-OPH, Sulf-2 levels could not be restored (Fig. 2c). QVD-OPH treatment effectively blocked bortezomib mediated cell death (Fig. S1d). These data suggests that downregulation of Sulf-2 either through ShRNA facilitates anoikis mediated cell death that is independent of caspase mediated cell death. In addition, we also determined whether reactive oxygen species (ROS) induction because of bortezomib treatment resulted in altered Sulf-2 expression by treating MCF10AT1 cells with and N-acetyl cystine (NAC), a ROS scavenger (Fig. S1d). NAC co-treatment does not rescue bortezomib mediated Sulf-2 downregulation and also does not alter cleaved PARP as well. These data suggest that bortezomib treatment downregulates Sulf-2 and is not dependent upon caspases-mediated apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Proteasomal inhibitors abolish Sulf-2 expression in MCF10DCIS breast cancer cells. a Proteasomal inhibitors abolished Sulf-2 expression in breast cancer cell lines. MCF10DCIS cells were treated with proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (5 μM), lactacystin (5 μM) and bortezomib (0, 25, 50 nM and 1 μM) for 16 h respectively. Cells were harvested and subjected to western blot analysis using anti-Sulf-2, anti-cleaved PARP and anti-β-actin antibodies. b MCF10DCIS cells were treated with proteasomal inhibitor bortezomib (0, 25, 50nM) for 16 h and subjected to real time analysis using Sulf-2 and 18S primers as described in materials and methods section. c MCF10DCIS cells were treated with proteasomal inhibitor bortezomib (50 nM) and QVD-OPH (10 μM) as indicated. Cells were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-Sulf-2, anti-cleaved PARP and anti-β-actin antibodies

Bortezomib treatment attenuated tumor growth and caused massive apoptotic lesions

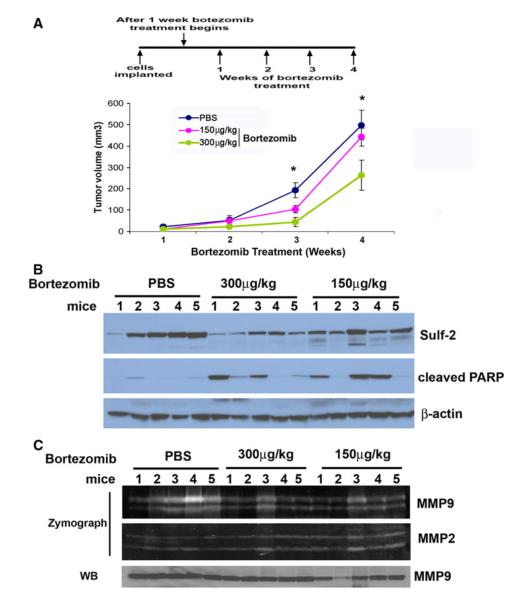

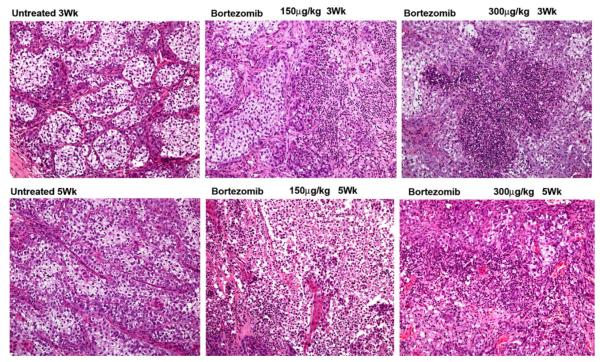

To further evaluate the effects of bortezomib on tumor growth, we treated two groups of mice (n = 18 or 9 mice/group) (with palpable tumors after 1 week of initial tumor cell implantation) with 0.150 and 0.300 mg/kg body weight twice weekly and one group of mice were treated with PBS. Bortezomib treatment drastically reduces tumor growth as monitored by caliper measurements at weeks 3, 4 and 5 (Fig. 2a) at doses of 0.300 mg/kg body. However, 0.150 mg/kg dose had marked effect till week 3, thereafter it was ineffective in restraining the tumor growth. As shown in Fig. 3a, tumor growth was attenuated compared to NTC cells (*p value <0.05, **p value <0.05). These data suggest that bortezomib treatment results in decreased tumor growth. Western blot analysis of lysates derived from xenografts indicate enhanced level of cleaved PARP and diminished level of Sulf-2 in bortezomib treated xenografts (5 mice/group as shown in western blot) (Fig. 3b). In addition, we also monitored effects of bortezomib on matrix metalloproteases as MMPs provide necessary trigger for progression to invasive carcinoma [18]. Zymography of bortezomib treated and untreated xenografts revealed that bortezomib treatment decreased MMP9 activities while little or no effect was observed on MMP2 (Fig. 3c). Similarly, western blot analysis show no significant change in total MMP9 levels (Fig. 3c, lower panel). Further, H&E staining reveals that bortezomib treatment completely disrupted the organized comedo structures and exhibited widespread massive apoptosis (Fig. 4a). These findings support our notion that bortezomib effectively restricts tumor growth by causing excessive cell death and by reducing MMP9 expression.

Fig. 3.

Bortezomib treatment decreases tumor growth in mouse mammary fat pad xenografts MCF10DCIS cells. a Graphical representation of tumor volume of xenografts of PBS treated and bortezomib treated (0.150 and 0.300 mg/kg body weight), twice weekly at week 1, 2, 3, 4 of tumor growth (*p value <0.05, t test). b PBS (five mice) and bortezomib treated (5 mice/clone) xenografts lysates were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies against Sulf-2, cleaved PARP, and β-actin antibodies. c PBS treated and bortezomib treated xenografts lysates were subjected to gelatin zymography as described in the materials and methods to detect activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9. Lower panel show western blot analysis of the above samples with anti-MMP 9 antibody

Fig. 4.

Bortezomib treatment causes massive apoptosis in MCF10DCIS cells derived mouse mammary fat pad xenografts. H&E staining of MCF10DCIS derived xenografts at weeks 3, and 5 of untreated or bortezomib treated mice (0.150 and 0.300 mg/kg body weight, twice weekly). Representative microscopic pictures PBS and bortezomib treated mouse xenografts are shown. Magnification 20×

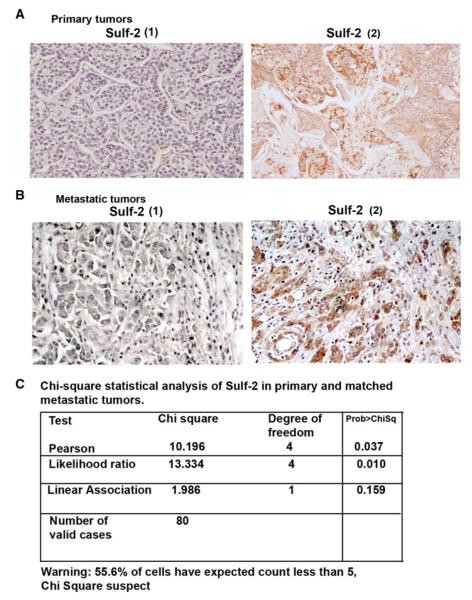

Sulf-2 is highly expressed in human breast cancer metastasis samples

To further evaluate the role of Sulf-2 in breast cancer we performed Sulf-2 expression in patient’s derived tumors (80 primary breast ductal carcinomas) and their matched nodal metastatic lesions from the same patients by immunohistochemistry as described in supplementary materials. Patient characteristics are described in Table 1 and representative Sulf-2 IHC in primary and matched metastatic patients is provided in Fig. 5a, b. Only ten of 80 patients (8 %) had high Sulf-2 expression in the primary tumors compared to 54 % of patients with high Sulf-2 in their autologous metastatic sites. The difference in the expression pattern of Sulf-2 between the primary versus metastatic sites was highly significant (p = 0.037, Pearson correlation) (Fig. 5c). There was positive correlation between Sulf-2 expression and metastatic phenotype (p = 0.037). These results indicate that elevated Sulf-2 is associated with breast cancer progression and metastasis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Total number | 80 | |

| Median age | 58 ± 15 | |

| Tumors associated with metastasis | 65 % | |

| Tumors associated with no metastasis | 35 % | |

| Histology | ||

| Ductal | 51 | |

| Ductal with associated metastasis | 29 | |

| Ductal without associated metastasis | 22 | |

| Lobular | 29 | |

| Lobular with associated metastasis | 23 | |

| Lobular without associated metastasis | 6 | |

| Grade | Primary | Metastasis |

| 1 | 26 (32.5 %) | 17 (21 %) |

| 2 | 39 (48.7 %) | 29 (36 %) |

| 3 | 15 (18.7 %) | 6 (0.07 %) |

| Sulf-2 expression in primary tumors | ||

| 0 (absent) | 37 (46.25 %) | |

| 1 (low) | 37 (46.25 %) | |

| 2 (high) | 6 (7.5 %) | |

| Sulf-2 expression in metastasis | ||

| 0 (absent) | 3 (4 %) | |

| 1 (low) | 34 (42 %) | |

| 2 (high) | 43 (54 %) | |

Fig. 5.

High levels of Sulf-2 are associated with metastatic tumors. a Primary breast cancer tissues stained with anti-Sulf-2 antibody showing no staining (score 1) and high staining (score 2). b Metastatic breast cancer tissues stained with anti-Sulf-2 antibody showing low staining (score 1) and high staining (score 2). c Chi-square statistical analysis of Sulf-2 in primary and matched metastatic tumors

Discussion

We have previously evaluated the role of Sulf-2 in progression from DCIS to IDC using MCF10DCIS cell line. This is the only cell line which mimics the human pathological progression of DCIS to IDC breast cancer and more importantly expresses high levels of Sulf-2. The progression to invasive ductal carcinoma is associated with disruption of basement membrane and invasion into surrounding tissues. Therefore this cell line offers unique system to evaluate changes as a result of Sulf-2 depletion.

The present study establishes the link between anoikis (matrix detachment induced cell death) and Sulf-2 and highlights putative pro-survival role of Sulf-2. Sulf-2 expression was diminished upon matrix detachment in two breast cancer cell lines MCF10DCIS and MCF-7 cells (Fig. S1a). Further, matrix detachment induced Sulf-2 downregulation was independent of caspase mediated cell death. ShRNA mediated Sulf-2 knockdown in MCF10DCIS cells resulted in increased matrix detachment induced cell death as revealed by increased PARP cleavage and decreased survival. These data suggest that Sulf-2 depletion promotes cell death in response to matrix detachment. This is in accordance with our previous report that Sulf-2 depletion results in apoptotic comedo lesions that might pave way for lumen formation in vivo [16]. In the present study we have provided evidence that downregulation of Sulf-2 upon matrix detachment promotes matrix detachment mediated cell death. The precedent for anoikis in lumen formation has been shown in 3D cell culture models [19]. Several oncogenes have been identified which promotes luminal filling by enhanced proliferation and by inhibiting detachment mediated-apoptosis (anoikis) [20, 21]. Consistent with these reports, our study supports the notion that Sulf-2 overexpression in breast cancer might promote tumorigensis during matrix detachment leading to survival.

Previous reports including the present study suggest that Sulf-2 is upregulated in breast cancer tissues and might promote tumorigenesis [4]. Therefore, therapeutically targeting this enzyme either by shRNA or by small molecule inhibitor may serve to improve our chances of inhibiting the progression of DCIS to IDC. We identified that proteasomal inhibitors such as MG132, Lactacystine and bortezomib attenuated Sulf-2 expression in several breast cancer cell lines. Further, bortezomib treated xenografts showed marked apoptosis and completely abolished comedo structures. Although it is likely that the effects elicited by bortezomib are predominantly due to its impact on proteasomal inhibition, bortezomib might affect several key signaling pathways thereby leading to decreased tumor growth apart from its effect on Sulf-2. Various target proteins have been identified that are downregulated by bortezomib treatment such as ERα, Erb2, desmoglein 2 [22–25]. Effectiveness of bortezomib treatment of breast cancer has been investigated before [26, 27], however information about stages of breast cancer where bortezomib will be more effective still needs to be addressed.

A recent study highlighted the tumor suppressor role of Sulf-2 in MDA-MB-231 cell line [5]. This study relied on forced expression of Sulf-2 and use of purified form of Sulf-2 protein. However no noticeable effect of purified Sulf-2 was observed in tumor growth in contrast to the tumor suppressive effects observed upon overexpressed Sulf-2. Since our data indicate that Sulf-2 could potentially be an oncogene in breast cancer and not a tumor suppressor, we opted to determine Sulf-2 expression in patient derived tissues and mouse xenografts to validate our in vitro based findings. Using these resources we believe that our data support the tumor promoting role of Sulf-2. Our data clearly indicate that elevated Sulf-2 expression in metastatic lesions compared to autologous primary tumors (p ≤ 0.037) although there was no correlation to grade of the tumor either in the primary tumors or in the metastatic lesions. The present study establishes the link between anoikis (matrix detachment induced cell death) and Sulf-2 and highlights putative pro-survival role of Sulf-2. In all, this is first report which highlights the role of Sulf-2 in matrix detachment mediated cell death that can be therapeutically targeted by proteasomal inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Shridhar’s lab for insightful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NCI, National Institutes of Health (CA106954-04), the Mayo Clinic (to VS) and the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST 2011-0006220).

Abbreviations

- Sulf-2

Sulfatase 2

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteases

- FGF2

Fibroblast growth factor 2

- HSPGs

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10585-012-9546-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Ashwani Khurana, Department of Experimental Pathology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, 200 First Street, S.W., 2-46 Stabile, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Deok Jung-Beom, College of Oriental Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, South Korea.

Xiaoping He, Department of Experimental Pathology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, 200 First Street, S.W., 2-46 Stabile, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Sung-Hoon Kim, College of Oriental Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, South Korea.

Robert C. Busby, Department of Experimental Pathology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, 200 First Street, S.W., 2-46 Stabile, Rochester, MN 55905, USA

Laura Lorenzon, Department of Surgery “A”, Second Faculty of Medicine, “La Sapienza” University, Rome, Italy.

Massimo Villa, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy.

Alfonso Baldi, Section of Oncology, Campus BioMedico University, Rome, Italy.

Julian Molina, Department of Oncology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, USA.

Matthew P. Goetz, Department of Oncology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, USA

Viji Shridhar, Department of Experimental Pathology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, 200 First Street, S.W., 2-46 Stabile, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

References

- 1.Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, et al. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chua CC, Rahimi N, Forsten-Williams K, et al. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans function as receptors for fibroblast growth factor-2 activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2. Circ Res. 2004;94(3):316–323. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000112965.70691.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morimoto-Tomita M, Uchimura K, Werb Z, et al. Cloning and characterization of two extracellular heparin-degrading endosulfatases in mice and humans. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(51):49175–49185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205131200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morimoto-Tomita M, Uchimura K, Bistrup A, et al. Sulf-2, a proangiogenic heparan sulfate endosulfatase, is upregulated in breast cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7(11):1001–1010. doi: 10.1593/neo.05496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson SM, Iskenderian A, Cook L, et al. Human Sulfatase 2 inhibits in vivo tumor growth of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer xenografts. BMC cancer. 2010;10:427. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khurana A, Liu P, Mellone P, et al. HSulf-1 modulates FGF2- and hypoxia-mediated migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71(6):2152–2161. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabe H. Cancer early dissemination: cancerous epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation and transforming growth factor beta signalling. J Biochem. 2011;149(6):633–639. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tait LR, Pauley RJ, Santner SJ, et al. Dynamic stromal-epithelial interactions during progression of MCF10DCIS.com xenografts. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(10):2127–2134. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller FR, Santner SJ, Tait L, et al. MCF10DCIS.com xenograft model of human comedo ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(14):1185–1186. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.14.1185a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nannuru KC, Futakuchi M, Varney ML, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 regulates mammary tumor-induced osteolysis by activating MMP9 and transforming growth factor-{beta} signaling at the tumor-bone interface. Cancer Res. 2010 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3251. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stetler-Stevenson WG. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2001;10(2):383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai J, Chien J, Staub J, et al. Loss of HSulf-1 up-regulates heparin-binding growth factor signaling in cancer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(25):23107–23117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narita K, Staub J, Chien J, et al. HSulf-1 inhibits angiogenesis and tumorigenesis in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66(12):6025–6032. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khurana A, Nakayama K, Williams S, et al. Regulation of the ring finger E3 ligase Siah2 by p38 MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(46):35316–35326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606568200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khurana A, Tun HW, Marlow L, et al. Hypoxia negatively regulates heparan sulfatase 2 expression in renal cancer cell lines. Mol carcinog. 2011;51(7):565–575. doi: 10.1002/mc.20824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khurana A, McKean H, Kim H, et al. Silencing of HSulf-2 expression in MCF10DCIS.com cells attenuate ductal carcinoma in situ progression to invasive ductal carcinoma in vivo. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(2):R43. doi: 10.1186/bcr3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai JP, Sandhu DS, Yu C, et al. Sulfatase 2 up-regulates glypican 3, promotes fibroblast growth factor signaling, and decreases survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47(4):1211–1222. doi: 10.1002/hep.22202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shekhar MP, Tait L, Pauley RJ, et al. Comedo-ductal carcinoma in situ: a paradoxical role for programmed cell death. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(11):1774–1782. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.11.6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debnath J, Mills KR, Collins NL, et al. The role of apoptosis in creating and maintaining luminal space within normal and oncogene-expressing mammary acini. Cell. 2002;111(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reginato MJ, Mills KR, Paulus JK, et al. Integrins and EGFR coordinately regulate the pro-apoptotic protein bim to prevent anoikis. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5(8):733–740. doi: 10.1038/ncb1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haenssen KK, Caldwell SA, Shahriari KS, et al. ErbB2 requires integrin alpha5 for anoikis resistance via Src regulation of receptor activity in human mammary epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 8):1373–1382. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powers GL, Ellison-Zelski SJ, Casa AJ, et al. Proteasome inhibition represses ERalpha gene expression in ER? cells: a new link between proteasome activity and estrogen signaling in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29(10):1509–1518. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marx C, Yau C, Banwait S, et al. Proteasome-regulated ERBB2 and estrogen receptor pathways in breast cancer. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(6):1525–1534. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marx C, Held JM, Gibson BW, et al. ErbB2 trafficking and degradation associated with K48 and K63 polyubiquitination. Cancer Res. 2010;70(9):3709–3717. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorch JH, Thomas TO, Schmoll HJ. Bortezomib inhibits cell–cell adhesion and cell migration and enhances epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced cell death in squamous cell cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(2):727–734. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones MD, Liu JC, Barthel TK, et al. A proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, inhibits breast cancer growth and reduces osteolysis by downregulating metastatic genes. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(20):4978–4989. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Codony-Servat J, Tapia MA, Bosch M, et al. Differential cellular and molecular effects of bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(3):665–675. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.