Abstract

Between 2004 and 2010, 189 adult patients were enrolled on the National Cancer Institute (NCI) cross-sectional chronic Graft-versus-Host disease (cGVHD) natural history study. Patients were evaluated by multiple disease scales and outcome measures including the 2005 NIH Consensus Project cGVHD severity score. The purpose of this study is to assess the validity of the NIH scoring variables as determinants of disease severity in severely affected patients in order to standardize clinician evaluation and staging of cGVHD. 125 of 189 patients met criteria for severe cGVHD on the NIH global score and 62 had moderate disease, with a median of 4 (range 1–8) involved organs. Clinician average NIH organ score and the corresponding organ scores performed by subspecialists were highly correlated (r=0.64). NIH global severity scores showed significant associations with nearly all functional and quality of life outcome measures including Lee Scale, SF-36 Physical Component Scale (PCS), 2 minutes walk, grip strength, range of motion and Human Activity Profile (HAP). Joints/fascia, skin, and lung involvement impacted function and quality of life most significantly and showed highest number of correlations with outcome measures. The final Cox model showing factors jointly predictive for survival contained the time from cGVHD diagnosis (>49 vs. ≤49 months, HR=0.23; p=0.0011), absolute eosinophil count of (0–0.5 vs. >0.5 cells/µL, HR=3.95; p=0.0006) at the time of NIH evaluation, and NIH lung score (3 vs. 0–2, HR=11.02; p <0.0001). These results demonstrate that NIH organs and global severity scores are reliable measures of cGVHD disease burden. Strong association with subspecialist evaluation suggests that NIH organs and global severity scores are appropriate for clinical and research assessments, and may serve as a surrogate for more complex sub-specialist exams. In this population of severely affected patients, NIH lung score is the strongest predictor of poor overall survival, both alone and after adjustment for other important factors.

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT) is curative for many diseases. However, roughly 50% of alloHSCT recipients develop chronic graft-versus-host-disease (cGVHD), a serious and potentially life threatening long-term complication.1 cGVHD is a multi-system alloimmune disorder characterized by immune dysregulation, immunodeficiency, impaired organ function and decreased survival. Five-year survival rates for patients who develop cGVHD range from 40% to 70% and complications from cGVHD are the primary cause of non-relapse mortality for patients greater than 2 years from transplant.1–3 Up to one-half of patients fail front-line therapy and require second-line therapies, which often results in partial or short-lived responses, drug toxicity, or decreased quality of life (QOL) and functional ability.4

Important barriers to clinical research in cGVHD include the absence of standardized criteria for diagnosis, staging, and response criteria in order to systematically study this rare disease5. Over the past several years, the transplant community has come together to systematically study cGVHD under the guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored cGVHD Consensus Project. The cGVHD Consensus Project is an international collaborative effort that has unified the transplant community's approach to the disease through the compilation of focused working groups.6–11

The purpose of this current study is to validate the NIH Organ Scoring and Global Severity Staging as determinants of cGVHD disease severity in a prospectively established cohort of patients. We utilized the cGVHD Organ Score proposed by Filipovich et al. in 20055, to standardize the criteria for staging after the diagnosis of cGVHD is made, to score cGVHD organ involvement and assess overall severity and the level of functional impairment. This tool was applied to a predominantly severely affected cGVHD patient population, which is primarily referral-based and enriched for organ manifestations most likely to contribute the largest burden of the disease. Here we present the results of 189 patients extensively evaluated on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) cGVHD Natural History study comparing detailed expert evaluations with the Consensus criteria tools.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional natural history study of cGVHD patients evaluated at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) between October 2004 and August 2010. The cGVHD program at the NIH has established a multidisciplinary clinic and research network for the study of the pathogenesis and natural history of cGVHD. The foundation of this program is based on the natural history protocol, Prospective Assessment of Clinical and Biological Factors Determining Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease (NCT00092235), which is an NCI Institutional Review Board approved, non-therapeutic study emphasizing cross-sectional data and specimen collection. Between October 2004 and August 2010, 217 consecutive patients were enrolled. Nine participants were ineligible due to inability to confirm cGVHD diagnosis. Two patients were eliminated because of the diagnosis of late-acute GVHD with no evidence of cGVHD. Finally, 17 of the remaining patients were pediatric and were not used for this investigation. Therefore, 189 adult patients met criteria as defined by the NIH cGVHD Consensus Criteria5 definition and were included in this evaluation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Population

| Gender | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 99 (52) |

| Female | 90 (48) |

| Disease | |

| ALL/AML/MDS | 78 (41) |

| CML | 30 (16) |

| CLL | 14 (7) |

| Lymphoma | 42 (22) |

| Multiple Myeloma | 15 (8) |

| Aplastic Anemia/PNH | 6 (3) |

| Other | 4 (2) |

| Stem Cell Source | |

| Bone Marrow | 35 (18.5) |

| Peripheral Blood | 153 (81) |

| Cord | 1 (0.5) |

| Relationship | |

| Related | 130 (69) |

| Unrelated | 59 (31) |

| Age | |

| < 40 | 58 (31) |

| 40≤x<60 | 110 (58) |

| >60 | 21 (11) |

| Recipient CMV Status at transplant | |

| Positive | 59 (31) |

| Negative | 50 (26) |

| Unknown | 80 (43) |

| Myeloablative | |

| Yes | 102 (54) |

| No | 86 (65) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.5) |

| HLA Matched | |

| Yes | 156 (83) |

| No | 29 (15) |

| Unknown | 4 (2) |

| Sex Mismatch | |

| M/M | 47 (25) |

| M/F | 44 (23) |

| F/F | 41 (22) |

| F/M | 41 (22) |

| Unknown | 16 (8) |

| Time from transplant | |

| ≤ 360 (<1 year) | 30 (16) |

| 360<×≤720 (1–2 years) | 23 (12) |

| 720<×<1080 (2–3 years) | 41 (22) |

| 1080<×<1800 (3–5 years) | 44 (23) |

| >1800 (>5 years) | 51 (27) |

| Classification | |

| Classic chronic GVHD | 166 (88) |

| Overlap chronic GVHD | 23 (12) |

| cGVHD Onsetα | |

| Progressive | 80 (42) |

| Quiescent | 41 (22) |

| De Novo | 67 (35.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.5) |

| Number of prior treatment regimens | |

| < 2 | 19 (10) |

| 2–3 | 72 (38) |

| 4–5 | 61 (32) |

| >5 | 35 (19) |

| Unknown | 2 (1) |

| Intensity of immunosuppression* | |

| None/mild | 49 (26) |

| Moderate | 71 (37) |

| High | 69 (37) |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; cGVHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; F, female; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; M, male; MM, multiple myeloma; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

Definition for cGVHD onset are as follows: progressive (acute GVHD progressed directly to chronic GVHD); interrupted (acute GVHD resolved, then chronic GVHD developed); de novo (acute GVHD never developed). Overlap chronic GVHD is defined as having feature of both chronic and acute GVHD, such as erythematous skin and diarrhea.

None/mild = single-agent prednisone o0.5 mg/kg per day; moderate = single-agent prednisone ×0.5 mg/kg per day and/or any single agent/modality; high = 2 or more agents/modalities±prednisone ×0.5 mg/kg per day.

The Natural History protocol involves comprehensive systematic multi-specialty patient evaluation, comprehensive history and physical examination, functional measurements and quality of life (QOL) assessments. Skin, oral, and salivary gland biopsies, imaging, and laboratory tests are also performed. During the one week evaluation, NIH Organ Scores and global severity scoring is performed by a mid-level provider with attending physician review.5 Of note, when scoring “lung” on the NIH Organ Score, the lung function score (LFS) is used when pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are available and only in the absence of PFTs, are the symptoms used to grade lung. The LFS is computed by the extent of FEV1 and DLCO compromise (see supplemental material).5 When discrepancy existed between pulmonary symptom or PFT scores the higher value was used for final scoring. All but 3 patients had PFTs available for scoring in our study population. In addition, patients also undergo extensive sub-specialist evaluation (SSE) with in-depth subspecialty grading of the key organs, such as the Schubert Scale for oral involvement12, Schirmer’s tear test and eye exam, and NIH Skin Response Scale9. Key organ assessments include a total of nine domains: Dental, Dermatology, Ophthalmology, Occupational Therapy and Physiatry, Pulmonary, Gynecology, Gastroenterology, and two laboratory assessments: platelets and liver function tests (including bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase). These scores are subsequently converted to a 4-point scale similar to the NIH Organ Score, in which 0 = no involvement, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe involvement (see supplemental materials for subspecialist evaluation and 4-point conversion scale). All patients were evaluated by subspecialists of Dentistry, Dermatology, Ophthalmology, Occupational Therapy and Physiatry, and Gynecology (females only). Pulmonology and Gastroenterology evaluations were only performed in select patients and scoring of these organs relied on PFTs and patient reported symptoms. All evaluations were performed by a limited number of subspecialists, (for example 1 of 2 dermatologists, 1 of 3 ophthalmologists, 1 of 3 physiatrists), all of whom are experts in the evaluation of GVHD with a minimum of 5 years experience, publications in the field of cGVHD and several were involved in the development of the NIH Consensus cGVHD criteria. The average NIH scores are calculated by dividing the total score by the number of total domains (organs) measured (8 for females and 7 for males), whereas the mean of the population is determined by averaging the means of all individual average NIH scores. Similarly, the SSE averages are calculated for each patient by dividing the total score by the total domains measured (8 for males and 9 for females). Note the SSE global scale includes a measure of platelet count, which is not currently used in the NIH organ scores. Patients also underwent nine continuous variable outcome measures {Lee Symptom Scale13; SF-36 (physical/mental)14; FACTBMT15; HAP score Maximal Activity Score/Adjusted Activity Score (MAS/AAS)16, 2 min walk test, grip strength, and joint range of motion (ROM)}. NIH scores were compared to categorical outcomes: intensity of immunosuppression scale (IIS)17, therapeutic intent of GVHD at enrollment (TI) as defined per Mitchell et al.18, and clinician 7-point global assessment of change (CGA)9. See supplemental material for complete definition of terms.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate associations between a set of predictors and a set of outcomes were initially determined. Statistical methods used in these univariate analyses included the following: Wilcoxon rank sum test, Mehta’s modification to Fisher’s exact test19, Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test20, Cochran-Armitage trend test21, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Spearman rank correlation. Spearman correlations are interpreted as follows: |r| >0.70=strong correlation; 0.5 < |r| <0.7 =moderately strong correlation; 0.3 < |r| < 0.5= weak to moderately strong correlation; |r| <0.3=weak correlation.

Survival analyses were done beginning at the date of entry onto the natural history protocol until death or last follow-up. Kaplan-Meier analyses and log-rank tests were used to determine the association between potential predictors and survival after entering on the trial. When data were initially evaluated in three or more groups (such as with quartiles for a continuous parameter), the unadjusted p-value presented represents the result for a comparison based on combining data into two groups with differing prognosis. The adjusted p-value is the unadjusted p-value multiplied by the number of implicit comparisons, which were performed in order to end up with the most significant result shown. Following these univariate analyses, Cox proportional hazards models were constructed to determine the joint association between the factors of potential interest and survival. Except as noted above, all p-values are two-tailed and presented without formal adjustment for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Patient Population

The patient population was well balanced for gender (male = 99, female = 90), with an average on-study age of 48 years (18 – 70 years) and a median time from transplant of 37 months (4 – 258 months) and median time from cGVHD diagnosis of 23 months (0–222)(Table 1). The majority of patients (89%) were transplanted for hematologic malignancies, and approximately one-half of the population was CMV positive at transplant (if status known). 69% had a related donor transplant and 83% were complete HLA matches. Sex mismatch was equally distributed between M/M, M/F, F/F, and F/M, and the majority (81%) received peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) as their graft source. 54% underwent a myeloablative preparative regimen. Seventy-four percent (n=140) patients were on moderate or high immunosuppression at the time of evaluation and 26% on none or mild.

cGVHD Characteristics

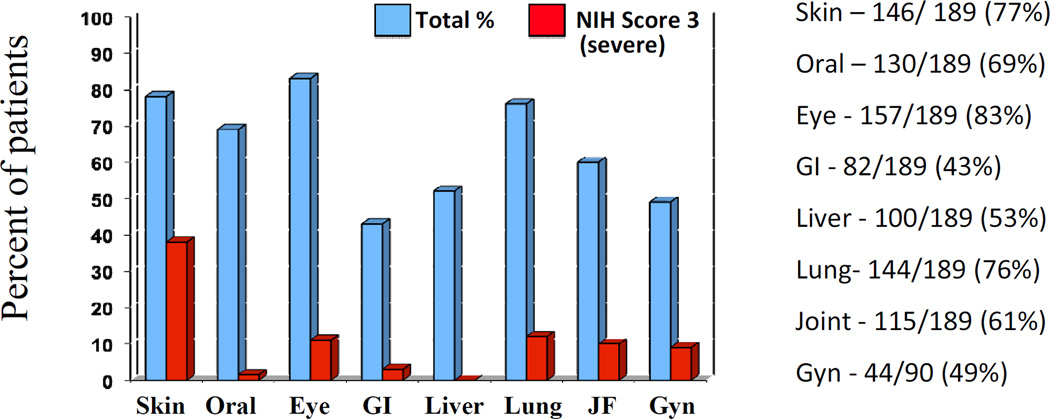

Overall125/189 (66%) of patients were categorized as severe by the NIH global score (Table 2); the median number of involved organs was 4 (1–7) for the moderate group and 5 (1–8) for the severe group. Patients had a median number of 4 prior treatment regimens (range 0–9); 88% were characterized as classic chronic GVHD, and 12% were overlap GVHD. The onset of cGVHD was progressive in 42%, de novo in 35%, and quiescent in 22% (Table 1). The median Lee Symptom Score was 34 (range 1–83). The most commonly involved organs were eye (83%), skin (77%), lung (76%), and oral (69%) (Figure 1, Table 2). Lung scores are based on the LFS, as calculated from PFT results. Only 3 patients were unable to complete PFTs and in those cases, lung score is based on symptoms only. Organ severity, however, was primarily driven by skin disease, followed by lung, joint/fascia, eye and genital involvement (Figure 1). Interestingly, in patients for whom self-report data was available (N=133) patients generally reported their global severity lower than the clinicians (Table 3), note the self-report questionnaire was added after the protocol opened and was therefore not available for the initial 56 patients enrolled on study.

Table 2.

NIH cGVHD Scores

| NIH Global Score | N (%) | ||

| 1 = mild | 2 (1) | ||

| 2 = moderate | 62 (33) | ||

| 3 = severe | 125 (66) | ||

| NIH Organ Score | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Skin | Liver | ||

| 0 = none | 42 (22) | 0 = none | 91 (48) |

| 1 = mild | 30 (16) | 1 = mild | 64 (34) |

| 2 = moderate | 46 (24) | 2 = moderate | 34 (18) |

| 3 = severe | 71 (38) | 3 = severe | 0 |

| Mouth | Lungs | ||

| 0 = none | 59 (31) | 0 = none | 45 (24) |

| 1 = mild | 104 (55) | 1 = mild | 79 (42) |

| 2 = moderate | 23 (12) | 2 = moderate | 42 (22) |

| 3 = severe | 3 (1.5) | 3 = severe | 23 (12) |

| Eyes | Joints and Fascia | ||

| 0 = none | 33 (17) | 0 = none | 75 (40) |

| 1 = mild | 66 (35) | 1 = mild | 40 (21) |

| 2 = moderate | 69 (36) | 2 = moderate | 55 (29) |

| 3 = severe | 21 (11) | 3 = severe | 19 (10) |

| GI Tract | Genital (female only n= 90) | ||

| 0 = none | 107 (57) | 0 = none | 46 (51) |

| 1 = mild | 62 (33) | 1 = mild | 13 (14) |

| 2 = moderate | 14 (7) | 2 = moderate | 13 (14) |

| 3 = severe | 6 (3) | 3 = severe | 18 (9) |

Figure 1.

Patients with cGVHD involvement per organ. A score of ≥1 on the NIH scale is reflected by the blue bar, and a score of 3 (severe) is represented by the red bar. Although eye, oral and skin are the most commonly involved organs, severity in the overall cohort was driven by severe skin disease and a high percentage of lung involvement.

Table 3.

NIH cGVHD Global Rating Scores

| Provider | Patient | |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 4 | 39 |

| Moderate | 64 | 65 |

| Severe | 121 | 29 |

| Unavailable | 56 |

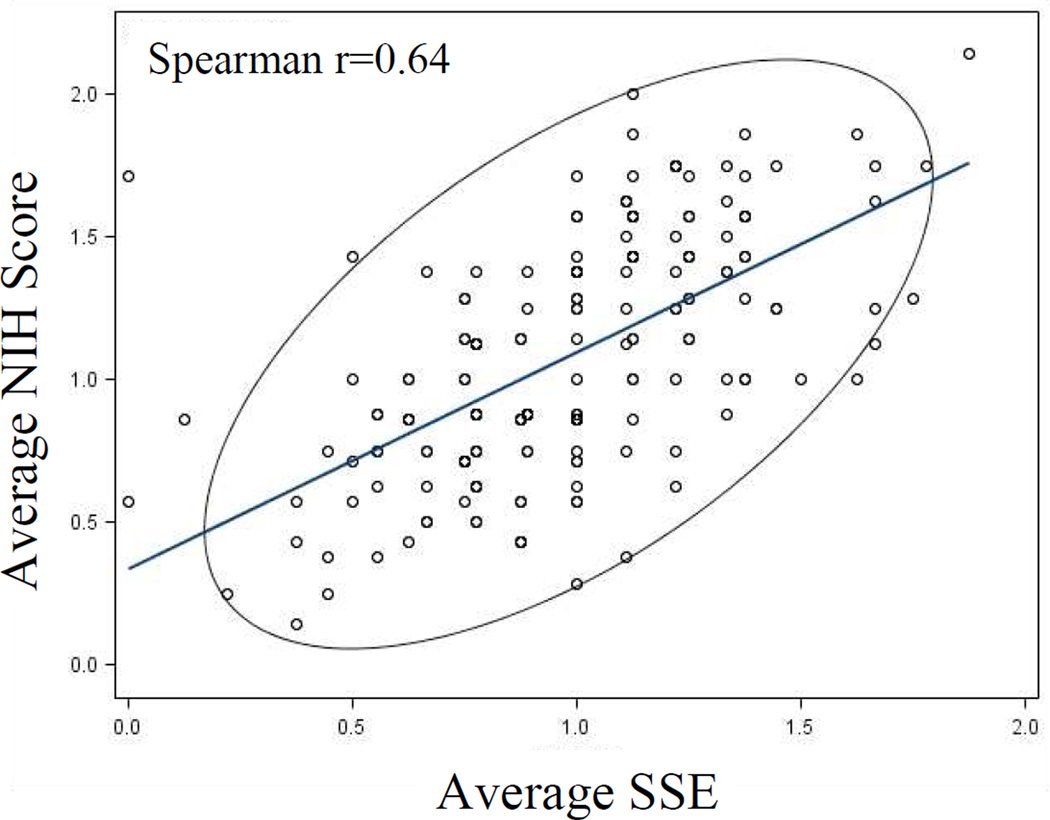

When comparing skin, eye, and oral GVHD score by clinician to subspecialty expert (SSE) scores (Dermatologist, Ophthalmologist, and Dentist), results were comparable. NIH scores for skin, mouth, and eyes were associated also with standard quantitative measures: % BSA, oral Schubert score, and Schirmer's test, each with two-sided P values of <0.0001 (not shown). The clinician average NIH score was 1.09 (0.14–2.14), which was comparable to the average SSE score of 0.98 (range 0.13 – 1.88). Direct comparison of the average SSE score to the average NIH score showed a moderately strong correlation (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.64) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of average NIH Organ score to the expert subspecialist evaluator (SSE) average score, shows a moderately strong correlation Spearman r = 0.64 (strong: r>0.70). The scores show impressive correlation considering the SSE score is a strictly objective assessment vs. the NIH score, which integrates patient reported symptoms and/or need for treatment.

cGVHD Score and Outcomes

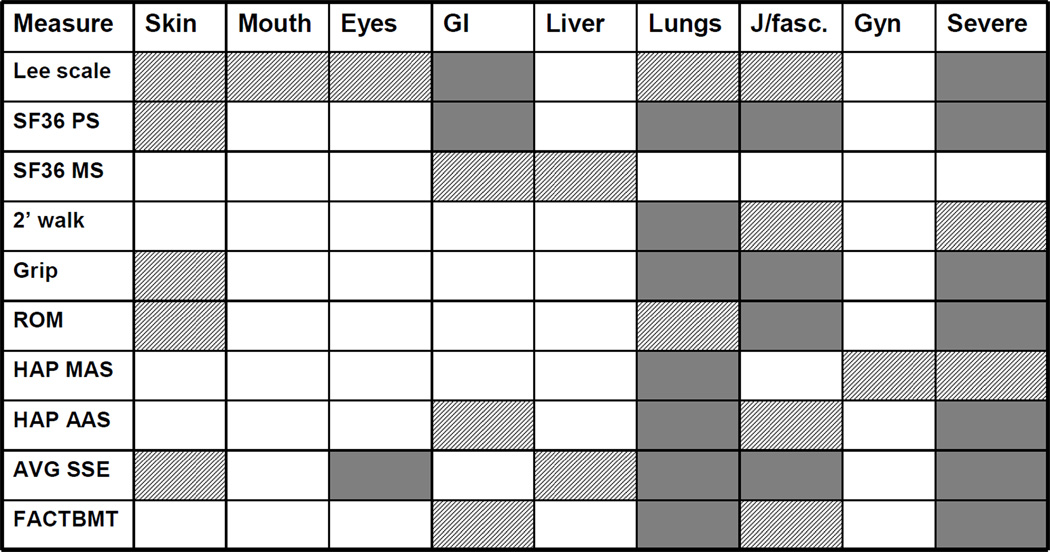

NIH global severity scores showed significant associations (p≤0.001 to p≤0.05) with almost all functional and quality of life (QOL) outcome measures: Lee Symptom Scale; SF-36 PCS; 2 minute walk; grip strength, range of motion, HAP (MAS and AAS); and FACT-BMT, with the exception of SF-36 MCS component (Figure 3). Joints/fascia, skin, and lung disease impacted function and quality of life most significantly as these scores showed highest number of significant associations with almost all outcome measures (Figure 3). The impact of skin on functional and QOL outcome measures is driven primarily by sclerotic involvement. Joints/fascia and skin scores, but not lung, were significantly associated with intensity of immunosuppression (IIS) (both p<0.0001), therapeutic intent at the time of evaluation (TI) (p <0.0001 for both), and clinician 7-point global assessment of change (CGA) (p< 0.0001 for both). Average NIH scores were also highly associated with SSE, IIS, TI and CGA. The Lee Symptom Scale was affected by organ involvement in most organs, but was most strongly correlated with GI score and an NIH Global Score of “severe”.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the NIH Organ Score to 10 outcome variables that are related to disease severity in patients with chronic disease. Scores with highly significant association with the outcome measure are indicated in the solid blocks (p<0.001) and those with a trend toward significance are represented by striped blocks (p<0.05).

cGVHD Score and Survival

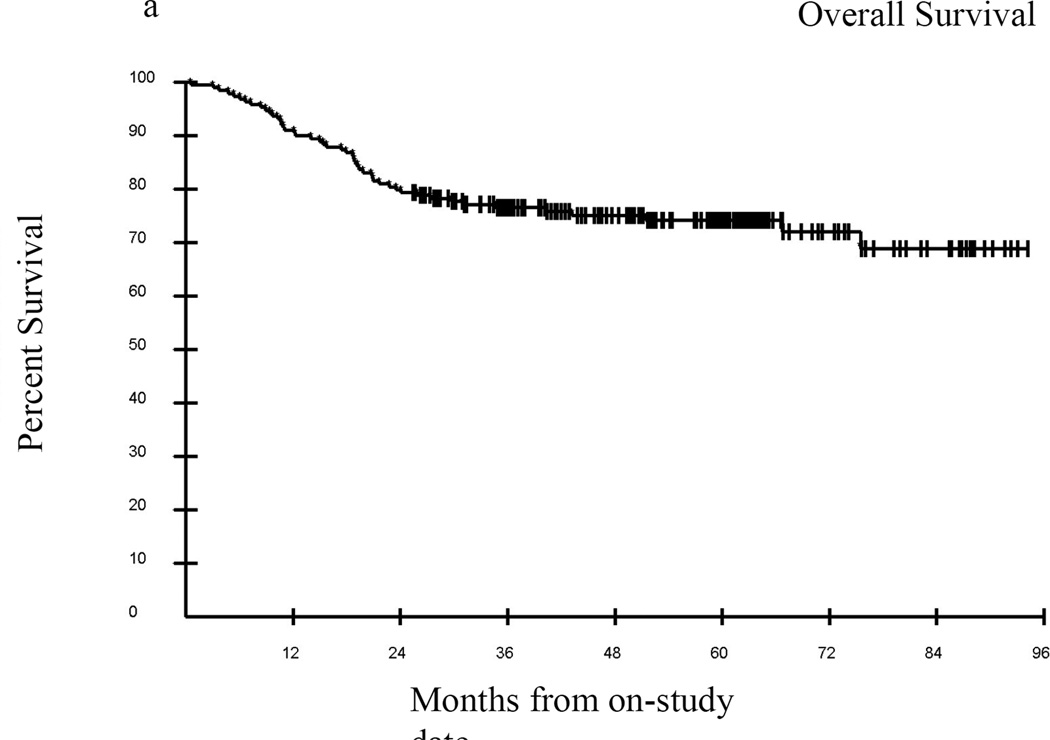

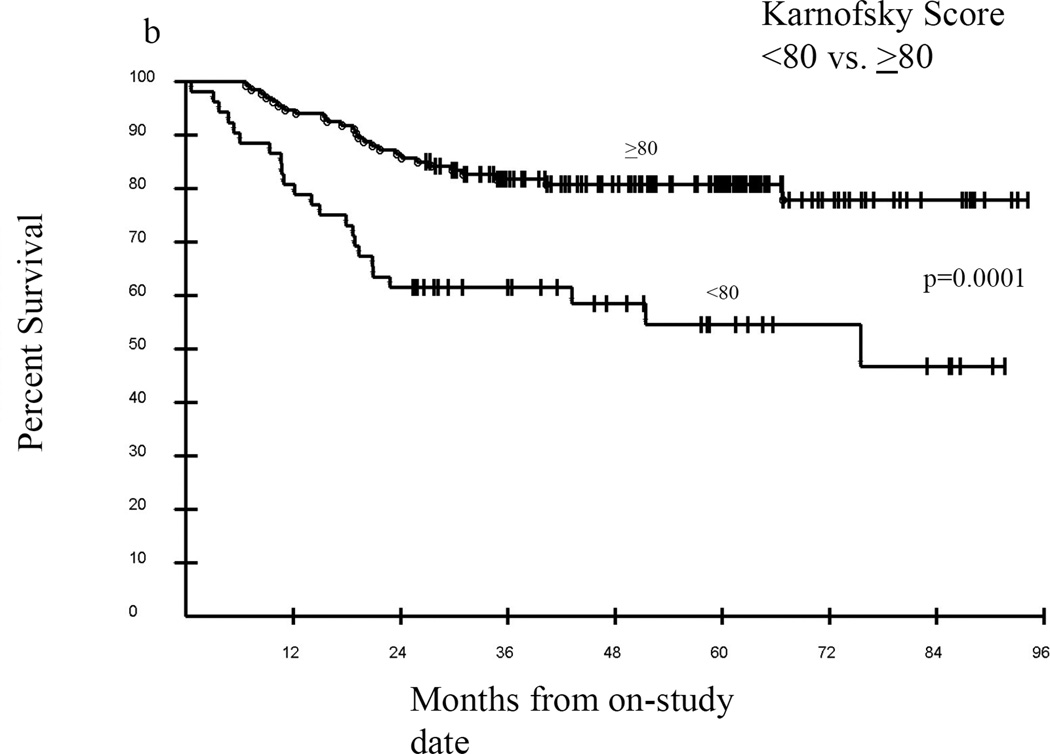

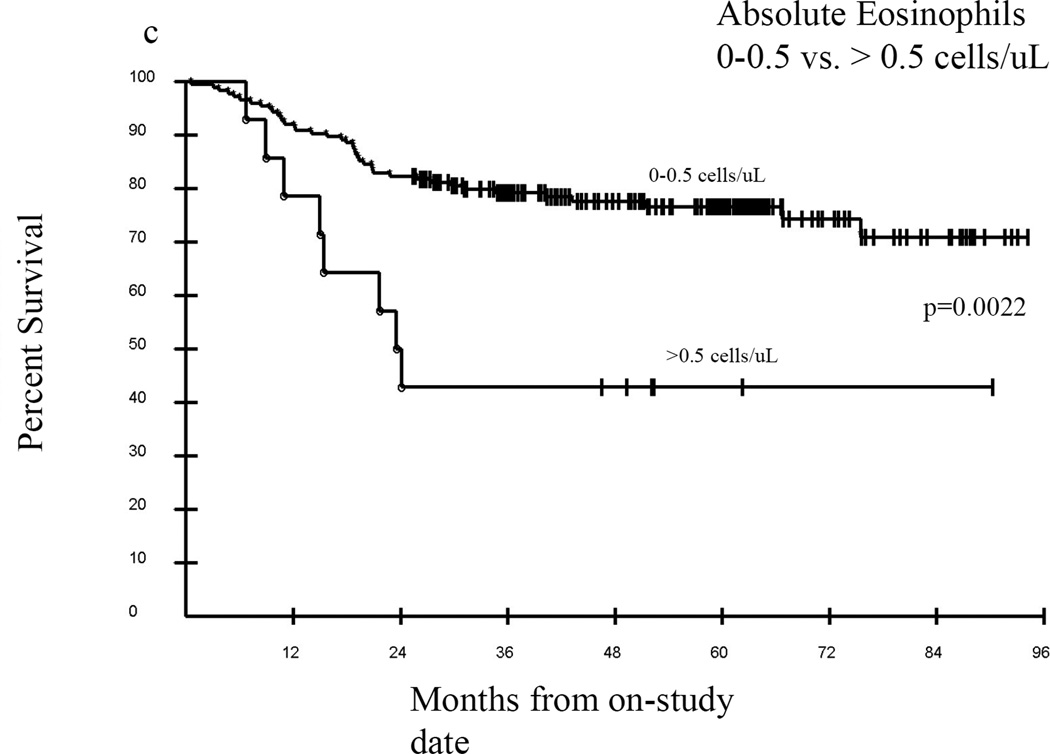

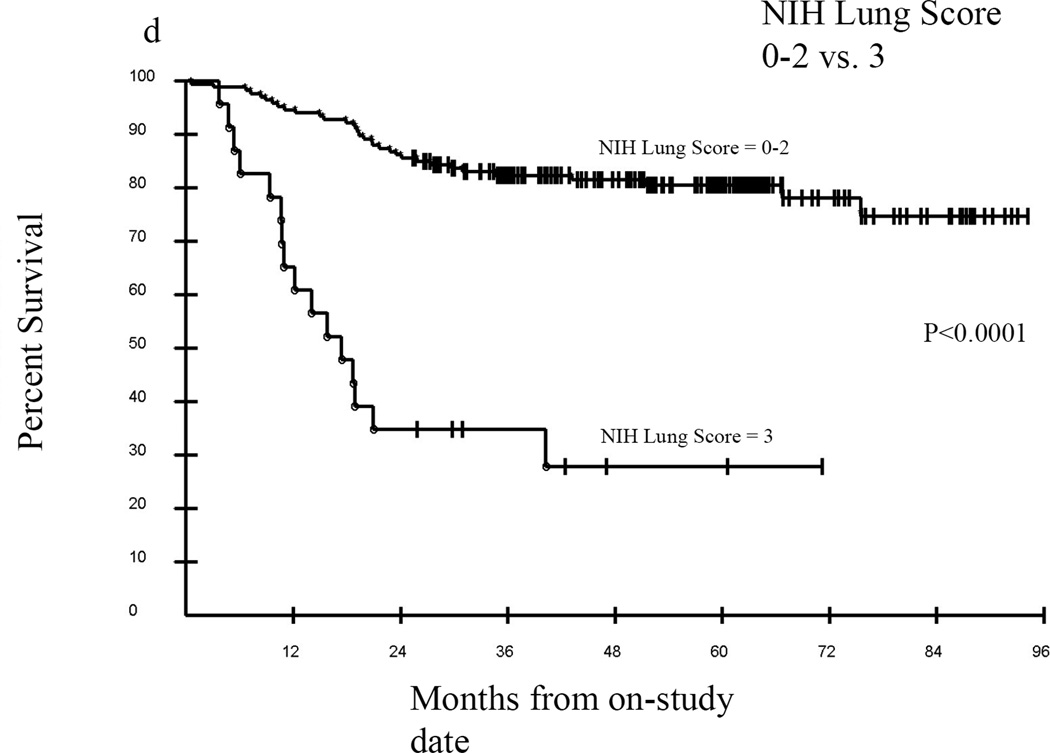

Median follow-up of surviving patients was 57.4 months, with an overall survival of approximately 76% at 36 months (Figure 4A). In univariate analyses a Karnofsky Performance Score (KPS) of ≥80 vs. KPS <80 was significantly associated with greater probability of survival, p=0.0001 (Figure 4B), as was an eosinophil count of 0–0.5 vs. >0.5 cells/uL, p=0.0022 (Figure 4C). Overwhelmingly, NIH lung score of 3 vs. <3 was the most strongly negatively associated with survival, with a 3 year estimated survival of 35% vs. 82% respectively, p<0.0001 (Figure 4D). In addition, FEV1 score >57% vs. ≤57%; time from cGVHD enrollment >49 months vs. ≤49 months; and NIH skin score 0–2 vs. 3, were associated with improved survival (data not shown). The average NIH Score <1.4 vs. ≥1.4 trended toward significance with an unadjusted p=0.07, p=0.21 adjusted (data not shown). In Cox proportional hazards analysis, adjusting for demographic and clinical parameters including time from transplant, time from cGVHD diagnosis, degree of immunosuppression, and known predictors of cGVHD mortality (hyperbilirubinemia, thrombocytopenia, eosinophilia, and low KPS), the final model contained time from cGVHD diagnosis of ≤49 months vs. >49 months (Hazard Ratio (HR) =0.23; 95% confidence Interval for HR=0.09 –0.56; p=0.0011), absolute eosinophil count of 0–0.5 vs. >0.5 cells/uL (HR=3.95; 95% CI for HR: 1.80 – 8.66; p=0.0006), and NIH lung score of 3 vs. 0–2 (HR= 11.02; 95% CI for HR: 5.67 – 21.41; p <0.0001).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the entire cohort (A) from the time enrolled on study. Karnofsky performance score (KPS) was associated with survival (B) in this cohort as was eosinophil count (C), but the best predictor of outcome was the NIH Lung Score (D), in which a severe score (=3) was the most likely indicator of poor survival p<0.0001.

DISCUSSION

This study adds to the growing body of recent literature supporting the NIH cGVHD Severity Scores as valid measures of disease severity in patients with cGVHD and represents an analysis of NIH Organs Scores and functional outcomes in moderate versus severely affected patients. The availability of a valid, reproducible tool to assess patients with cGVHD provides a universal scale to measure cGVHD in clinical trials and a common language among transplant physicians. This current study, in contrast to reported studies which included enrolled patients at transplant centers22–24, focuses on a referral population of patients enriched for severe and often disabling manifestations of cGVHD which are likely to contribute most significantly to patient morbidity. We performed, in a cross-sectional, prospective study design, a large set of clinician and patient reported outcome measures including the organ-specific subspecialist evaluations to assess the validity of the NIH consensus proposed scores.

Some degree of variability is expected between clinician and subspecialist scores, as the NIH organ score integrates subjective, patient-reported symptoms and impairment of function, whereas the expert evaluator scores are based on objective examination only. Nevertheless, a high degree of association was present between clinician and subspecialty expert scores, providing important evidence that NIH score can be used as a simple measure to adequately assess organ involvement. Recent studies also report validity in using the NIH scores as correlates of quality of life24 or over time as therapy response criteria25. Jacobsohn, et al. found similar concordance between NIH skin score and more in depth skin evaluations. In addition, change in NIH skin score correlated well to the Lee Symptom Scale and ultimately to overall survival.25

We demonstrated a strong correlation between NIH global stage and all outcomes (except SF-36 MCS), which validates this classification as a measure of cGVHD global severity. Severe NIH stage in our study population was driven significantly by the presence of sclerotic skin, joints-fascia, and/or lung involvement and involvement of these organs also has the greatest effect on function and quality-of-life as assessed by patient report measures as well as objective measures, such as grip strength and 2 minute walk time. This is similar to results of the Chronic GVHD Consortium study by Arai et al, where skin, lung and eye were found to be the most significant indicators of severity in their study22. Although the eyes were most frequently affected in our cohort, unlike Arai et al22, ocular involvement did not appear to impact functional or QOL outcome measures, or overall disease severity. Similarly, oral involvement was common, but also had minimal effects on outcome measures. This suggests the need for organ-specific outcome measures, such as the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP)26 or Ocular surface Disease index (OSDI)27 scales, when evaluating organ-specific interventions. This is an important consideration in clinical trials or interventions specifically targeted to a single organ or disease manifestation, whereas a more sensitive and specific scale may be needed to pick up changes that may go uncaptured on the NIH Organ Score. Despite the rarity of gastrointestinal involvement in our population, it was one of the most significant factors associated with a high score on the Lee Symptom Scale. Interestingly, although two-thirds of our population scored ‘severe’ on the global scale and NIH severity was significantly associated with almost every outcome measure evaluated, patients routinely self-reported their severity lower than the clinician. This may reflects the resiliency of this patient population with chronic illness.18 In fact, each patient was asked if they knew before transplant what their current outcome would be, would they choose transplant again. Almost universally patients responded that they would undergo transplant again knowing the impact that cGVHD would have on their life.

We also found in univariate analysis that KPS, a known prognostic indicator for patients with cGVHD, was associated with survival in our population as well. We observed a trend toward significance between average NIH score and the NIH global severity score and survival, which was seen in the Arai study22, but longer follow up of our cohort is needed to establish statistical significance. Thrombocytopenia and progressive onset of cGVHD, which are associated with poorer outcomes when present at the time of cGVHD diagnosis23, were not associated with poor outcomes in our population. The disparity of this finding to existing literature, likely reflects the fact that few of our patients evaluated on this study are newly diagnosed, rarely had acute GVHD features, and are far out from transplant with the median time from transplant in this cohort is 37 months, with a median time from cGVHD diagnosis of 23 months. In fact as previously reported, high platelet counts, thought to be non-specific indicators of inflammation, are associated with more severe disease in our patient population.17

Overwhelmingly, the most significant association in our study was the impact of NIH lung score on overall survival. Overall survival at 36 months for those with a lung score of 3 versus < 3 were 35% versus 82%, respectively. Lung dysfunction has significant influence on NIH global severity score as the score is weighted for lung involvement (lung score 1 = moderate; lung score 2 or 3 = severe). The high rate of lung dysfunction in our patient population (76% total, 34% severe) may explain the profound impact of the NIH lung score on overall survival. It is important to note, that the NIH lung score does not discriminate between lung GVHD and lung dysfunction otherwise classified. Patients with lung cGVHD or bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) have an extremely poor prognosis, lack effective therapeutic options, and have a mortality of 60–100% in most series.28 Although patients that meet criteria for BOS may fall into any of the NIH lung score categories (1–3), only those with the most severe disease (DLCO or FEV1 <39%) or a lung function score (LFS) of 10 –12 meet the criteria for a lung score of 3. The LFS is computed by the extent of FEV1 and DLCO compromise (see supplemental material).5 This implies that stratification of lung dysfunction in the NIH score has a profound impact on prognostic value of pulmonary function. Further analysis of this subset of patients with elevated NIH lung score is currently underway in order to delineate the differences between GVHD lung involvement and other lung dysfunction and impact on outcomes and survival.

Although eosinophilia was infrequently observed in this patient population (14/189), it was found to be an important independent prognostic factor for survival. Eosinophilia has been identified as a harbinger of the development of both aGVHD and cGVHD29,30, however other studies have shown an association between eosinophilia and favorable outcomes following alloHSCT31 and lower grade cGVHD32,33,34. These studies did not utilize NIH diagnostic criteria and eosinophilia was evaluated at the time of cGVHD diagnosis, in contrast to the current study, where patients are far from time of initial cGVHD presentation. Eosinophilia in our patient population did not correlate with specific clinical manifestations and the mechanism of the association of eosinophilia and poor survival is unclear, but merits further investigation. Although we included intensity of immunosuppression in our model, we did not evaluate prednisone as an independent factor, which may also influence the impact on eosinophilia.

Potential limitations in our study include the severity of disease encountered in our patient population that may not be representative of typical patient cohorts at other transplant centers. Because of the nature of a cross-sectional study and because this represents a referral population, our population was enriched for refractory or persistent cGVHD manifestations. In particular, we identified a high incidence of lung, sclerotic skin and joint/fascia involvement. In the same manner, the time from transplant in our population (approximately one-half of patients were >3 years from transplant) is not representative of all time points in the cGVHD disease course, particularly the onset of cGVHD manifestations. However, despite these limitations, this referral population and cross-sectional design allow data to be acquired from affected patients treated at dozens of transplant centers in the US and internationally. The Natural History study on which these patients were evaluated allows for detailed evaluations with extensive, precise and consistent data capture. This facilitated examination of a large population of patients with significant disease burden, particularly those with less common and most disabling manifestations. The availability of parallel organ-specific scoring by subspecialists and clinicians allowed a unique opportunity to independently validate NIH scores generated by the transplant clinician.

In conclusion, this study supports the utility of the NIH cGVHD Severity Scores as adequate indicators of disease severity in patients severely affected by chronic GVHD and may effectively substitute for subspecialist evaluations in longitudinal, prospective transplant studies. Additionally, NIH Lung Score is the single most significant determinant of survival in this cohort.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

This work was supported by the Center for Cancer Research, Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge the exhaustive efforts of Niveen Atlam, Zetta Blacklock-Schurver, Jaime Brahaim, Ashley Carpenter, Jane Fall-Dickson, Lynn Gerber, Jean Pierre Guadagnini, Frances Hakim, Oleh Hnatiuk, Matin Imanguli, Michael Krumlauf, Li Li, Barbara Mittleman, Maria Turner, and Michael Robinson. Finally, we express sincere gratitude to our patients and their families.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The authors are employees of the United States Government, and, as such, this work was done in that capacity. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no relevant conflicts to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SZP conceived the study with input from RG, CS, JGB and DF. KB, LG, DP, EWC, SAM, KMW, MD, RB, CB, JM, DA, DNA, TT, GJ, LC, AB, PS, JS, JGB, CS, and SZP implemented the study and provided clinical care. AC and KC provided research support. SMS provided statistical support. KB, LG, and SZP analyzed data and wrote the manuscript, with input from EWC and SAM.

References

- 1.Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215–233. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter PA. Late effects of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2008;21:309–331. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora M, Klein JP, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Chronic GVHD risk score: a Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research analysis. Blood. 2011;117:6714–6720. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-323824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora M, Nagaraj S, Witte J, et al. New classification of chronic GVHD: added clarity from the consensus diagnoses. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:149–153. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shulman HM, Kleiner D, Lee SJ, et al. Histopathologic diagnosis of chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: II. Pathology Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz KR, Miklos DB, Fowler D, et al. Toward biomarkers for chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: III. Biomarker Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, et al. Measuring Therapeutic Response in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic Graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:375–396. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin PJ, Weisdorf D, Przepiorka D, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: VI. Design of Clinical Trials Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schubert MM, Sullivan KM, Morton TH, et al. Oral manifestations of chronic graft-v-host disease. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1591–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ, Joffe S, Kim HT, et al. Physicians' attitudes about quality-of-life issues in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104:2194–2200. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Cella DF, et al. Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) scale. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:357–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daughton DM, Fix AJ, Kass I, et al. Maximum oxygen consumption and the ADAPT quality-of-life scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982;63:620–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grkovic L, Baird K, Steinberg SM, et al. Clinical laboratory markers of inflammation as determinants of chronic graft-versus-host disease activity and NIH global severity. Leukemia. 2012;26:633–643. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell SA, Leidy NK, Mooney KH, et al. Determinants of functional performance in long-term survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:762–769. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta C, Patel NK. A network algorithm for performing Fisher’s exact test in r x c contingency tables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78:427–434. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollander M, Wolfe DA. Nonparametric Statistical Methods, Second Edition. ed Second. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1999. pp. 189–269. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1990. pp. 79–129. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arai S, Jagasia M, Storer B, et al. Global and organ-specific chronic graft-versus-host disease severity according to the 2005 NIH Consensus Criteria. Blood. 2011;118:4242–4249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuzmina Z, Eder S, Bohm A, et al. Significantly worse survival of patients with NIH-defined chronic graft-versus-host disease and thrombocytopenia or progressive onset type: results of a prospective study. Leukemia. 2012;26:746–756. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pidala J, Kurland B, Chai X, et al. Patient-reported quality of life is associated with severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease as measured by NIH criteria: report on baseline data from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2011;117:4651–4657. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-319509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobsohn DA, Kurland BF, Pidala J, et al. Correlation between NIH composite skin score, patient-reported skin score, and outcome: results from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2012;120:2545–2552. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424135. quiz 2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hegarty AM, Hodgson TA, Lewsey JD, et al. Fluticasone propionate spray and betamethasone sodium phosphate mouthrinse: a randomized crossover study for the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:271–279. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, et al. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:615–621. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams KM, Chien JW, Gladwin MT, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. JAMA. 2009;302:306–314. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeel D, Rubio MT, Damaj G, et al. Hypereosinophilia as a presenting sign of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:1797–1800. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200212270-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobsohn DA, Schechter T, Seshadri R, et al. Eosinophilia correlates with the presence or development of chronic graft-versus-host disease in children. Transplantation. 2004;77:1096–1100. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000118409.92769.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aisa Y, Mori T, Nakazato T, et al. Blood eosinophilia as a marker of favorable outcome after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Transpl Int. 2007;20:761–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Przepiorka D, Anderlini P, Saliba R, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:1695–1700. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim DH, Popradi G, Xu W, et al. Peripheral blood eosinophilia has a favorable prognostic impact on transplant outcomes after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmad I, Labbe AC, Chagnon M, et al. Incidence and prognostic value of eosinophilia in chronic graft-versus-host disease after nonmyeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1673–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.